The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Please note: there is no sovereign debt risk in Japan!

Sometimes you read an article that clearly has a pretext but then tries to cover that pretext in some (not) smart way to make the prejudice seem reasonable. That is the impression I had when I read this Bloomberg opinion piece by William Pesek (January 31, 2011) – Pinnacle Envy Signals New Bubble Is Inflating – which I was expecting to be about real estate bubbles but which, in fact, turned out to be an erroneous blather about Japanese debt risk. Please note: there is no sovereign debt risk in Japan!

Pesek’s smokescreen is about skyscrapers which reflect the irrational and out-sized egos of the developers who fund and build them and the policy makers who approve them. In some cases, the two groups might be the same or overlap heavily. Pesek lists some examples that have clearly been examples of “mis-allocated capital”.

He introduces Japan by noting that as an earthquake-prone nation it seems odd that they would try to build the world’s largest skyscraper – the 634 metre Tokyo Sky Tree tower. The project is being funded by the six major TV networks in Japan including NHK which is the public broadcasting corporation. The tower is being built to allow digital television to be introduced – the current facilities are not high enough given the other skyscrapers in Tokyo. The other engineering data suggests that the earthquake issues have been dealt with in the design.

But Pesek doesn’t want to go into these details he rather wants to leave the impression that building such a tower is the manifestation of a complacent country that has become tainted by extravagance. He says without reference to the telecommunications issues that other reporting on the project emphasise that:

The thing about record-breaking structures is that they often say as much about arrogance as they do about wealth, ambition and technology. In Japan’s case, for example, free money breeds complacency as well as bubbles. Zero rates gave politicians the idea they could issue debt forever without consequence.

In some case record-breaking structures do signal “arrogance” and ego-driven behaviour (excessive that is). But whether the Tower in Japan reflects that underlying motive is one thing – although the evidence suggests that engineering and networked communication issues have driven the design.

But there is no sensible analogy that can be drawn between the decision to build that tower and the way the Japanese government (including the Bank of Japan) runs its fiscal and debt-issuance policies.

The reference to “free money” is also erroneous. Commercial interest rates are low in Japan but not zero. There is no “free” money in Japan for property developers so why use this emotional term.

Anyway, Pesek’s pretext was to comment on the Standard & Poor downgrading of Japanese sovereign debt last week to AA- (the fourth-highest level). He says:

Those days are over, as Standard & Poor’s reminded Japan last week by cutting its rating to AA-, the fourth-highest level. Still, the fact remains that as Tokyo construction crews finish their ode to architectural excess, the government has built up a monumental debt load that smacks of hubris … Politicians and developers are often both optimists and gamblers. Ambition and excess get so fused together that they forget where one ends and the other begins. Japanese politicians put their nation’s future on a credit card, believing their methods of fiscal management would avert crisis. The bill is now coming due. A Greece-like crash isn’t the best-case scenario, but then neither can one be ruled out.

First, he hasn’t made a case (and the evidence suggests otherwise) that the new communications tower is an “architectural excess”. Whether it is or not is a separate argument and hardly likely to reflect on the nature of fiscal policy conduct by the Japanese government.

Second, the conflation of developers and the Japanese government as optimists and gamblers is erroneous. Clearly, property development is a gamble because the financiers have to raise the funds and then risk them if the project fails. The national government of Japan faces no such risk.

Third, hubris refers to “haughty or arrogant” behaviour. The rising Public debt to GDP ratio in Japan (now over 200 per cent) reflects the difficulties that economy has faced over two decades and some poorly implemented attempts by conservative governments to implement fiscal austerity (for example, 1997) at a time when private spending was too weak to cope.

The fact is that the Japanese economy has required significant support from budget deficits over a long period given the relative high propensity to save by the private domestic sector. I do not call implementing a policy stance that has allowed economic growth to be sustained in the face of private spending patterns which were constraining stronger growth to be arrogant or haughty.

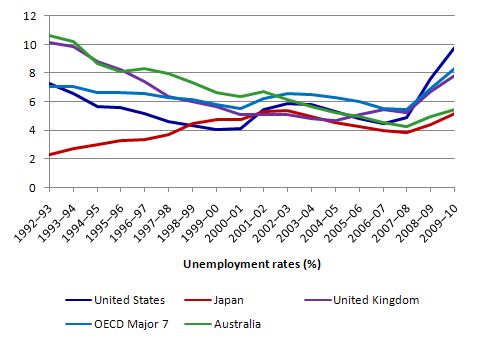

In fact, I would call that responsible economic management. While I might question the size of the budget deficits in Japan (they have been too small) I would note the following graph which shows annual unemployment rates (1993-94 to 2009-10) for some selected countries. While the Japanese economy has been performing poorly in terms of growth and has been undergoing structural changes with respect to deeply-held cultural norms (for example, the diminution of lifetime employment), it has still outperformed all the major economies in terms of keeping its jobless rate low.

I remind readers that unemployment is the single largest waste of economic resources and source of income loss. The on-going public deficits in Japan have contributed positively to this low unemployment outcome and very muted labour market response to the recent crisis. I do not call that hubris.

Anyway Pesek then launches into a rave about how Japan’s fiscal position (in the face of an ageing society) and its public debt levels are “nothing less than toxic” and that in terms of the current government’s plan to join the fiscal austerity bandwagon, “(m)investors don’t understand that supposed commitment either”.

He also chooses to suggest that the ratings agencies were in some way “right” in 2002 when S&P, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch downgraded Japan last time and that the reaction of the Japanese government was poor.

I discuss the recent history of Japan’s sovereign debt run-ins with the credit rating agencies in this blog – Ratings agencies and higher interest rates. Pesek certainly doesn’t record what happened – it would injure his pretext if he did and so he relies on his readers either not knowing what happened or forgetting.

In a nutshell, in November 1998, the day after the Japanese Government announced a large-scale fiscal stimulus to its ailing economy, Moody’s made the first of a series of downgradings of the Japanese Government’s yen-denominated bonds, by taking the Aaa (triple A) rating away. By December 2001, they further downgraded Japanese sovereign debt to Aa3 from Aa2. Then on May 31, 2002, they cut Japan’s long-term credit rating by a further two grades to A2, or below that given to Botswana, Chile and Hungary.

In a statement at the time, Moody’s said that its decision “reflects the conclusion that the Japanese government’s current and anticipated economic policies will be insufficient to prevent continued deterioration in Japan’s domestic debt position … Japan’s general government indebtedness, however measured, will approach levels unprecedented in the postwar era in the developed world, and as such Japan will be entering ‘uncharted territory’.”

The Japanese government (Finance Minister) responded very sensibly: “They’re doing it for business. Just because they do such things we won’t change our policies … The market doesn’t seem to be paying attention.”

Indeed, the Government continued to have no problems finding buyers for their debt, which is all yen-denominated and sold mainly to domestic investors. It also definitely helped Japan that they had such a strong domestic market for bonds.

In the New York Times (July 6, 2002), the logic of the rating was questioned:

How … could a country that receives foreign aid from Japan have a better rating than Japan itself? Japan, with an economy almost 1,000 times the size of Botswana’s, has the world’s largest foreign reserves, $446 billion; the world’s largest domestic savings, $11.4 trillion; and about $1 trillion in overseas investments. And 95 percent of the debt is held by Japanese people.

The UK Telegraph article said of Japan at the time:

Bizarrely, securities backed by mortgages sold to people without the income to service the debt they were taking on were being judged a better credit risk than the sovereign government of Japan, with the ability in extremis both to raise taxes and print money to avoid a default.

Rating sovereign debt according to default risk is nonsensical. While Japan’s economy was struggling at the time, the default risk on yen-denominated sovereign debt was nil given that the yen is a floating exchange rate.

In general, the Bank of Japan showed in the period from the mid-1990s onwards that they can keep interest rates very low (zero) and issue as much government debt as they wanted even in the face of consistent credit rating agency downgrades.

So if a government stands up to the agencies their impact is likely to be minimal. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

Further the Japanese government has it within their capacity to stop issuing debt whenever they want to change the regulations/laws that dictate these absurd voluntary constraints.

And after claiming that Japan is “lucky credit rating companies have been so generous” he gives the whole game away:

Yes, Japan is rich, has trillions of dollars of household savings and a bond market that keeps virtually all public debt onshore. Its fiscal trajectory, though, is dismal. The only thing regrettable here is that politicians aren’t getting the message.

Talk about a towering display of denial. Even if you think the logic behind the Skyscraper Curse is shaky, concerns about a Japanese debt crash are based on solid foundations.

I suggest Pesek first of all consult some structural engineers to learn more about the seismic-proofing of the nearly completed Tokyo Tower to get some reassurance that the building is on “solid foundations”. My knowledge is that it is very well proofed against earthquakes but that is what my engineering pals tell me.

Then I suggest Pesek write an essay on the implications of issuing risk-free public debt to provide a modest return to the “trillions of dollars of household savings” without recourse to foreign-currency denominated sources while maintaining economic growth with spending which provides the source of that “household saving” and keeps unemployment relatively low.

The Japanese treasury and central bank understand this. The conservative politicians might be getting spooked but then they are probably being advised by young PhD graduates from US universities who have been poorly educated.

Let me say there will be no Japanese sovereign debt crash – now, soon nor ever. I challenge Pesek to articulate when he thinks that crash is likely to occur and in what form it will take. He will not do that of-course because he has filed his copy and is busy writing some more nonsense that his un-informed readers will then get worried about.

The fact is that the Japanese government never has any problem issuing its debt at low yields and at least the bond traders understand that.

But misconceptions about how different monetary systems shape a nation’s opportunities are fairly broadly held – even among so-called progressives. Take the latest column by Paul Krugman in the New York Times (January 27, 2011) – Their Own Private Europe – which purports to expose how poorly conceived Republican response to the US President’s State of the Union address was.

Krugman quotes a section of the Republican response (from Paul Ryan) as being something that “caught” his eye:

Just take a look at what’s happening to Greece, Ireland, the United Kingdom and other nations in Europe. They didn’t act soon enough; and now their governments have been forced to impose painful austerity measures: large benefit cuts to seniors and huge tax increases on everybody.

That response which is trying to claim that if you don’t act to reduce deficits early crisis will follow is clearly nonsensical. The global financial crisis and subsequent deep real economic recession had nothing to do with “deficits” being too large. Quite the opposite in fact.

Prior to the crisis, if governments had have used expansionary fiscal policy (increasing deficits) to ensure that economic growth absorbed the persistently high unemployment then private savings could have been higher and there may have been less reliance of private credit growth to underpin economic growth. The overall national accounting relationships are clear – government surplus equals non-government deficit. The causality between the two is less clear and has to be inferred from the context and the circumstances.

But when a government is pursuing fiscal austerity (either generating surpluses or trying to) then the only way the economy can grow is if the non-government sector is recording deficits (or trying to). With external deficits, this will manifest in the form of private domestic deficits (typically). A growth strategy founded on increasing private indebtedness (the stock manifestation of these deficit flows) is unsustainable and eventually the fiscal drag is exposed as, say, households try to increase their saving.

Further, post-crisis, the pursuit of fiscal austerity and/or the reluctance by governments to expand their deficits to an appropriate scale given the circumstances surrounding non-government spending has prolonged the crisis unduly and caused long-term unemployment to rise in most countries. The crisis could have been attenuated in its impact and even largely sequestered to the financial sector if governments had have acted responsibly with respect to their fiscal responses.

But the other major problem with this argument is that it collects “Greece, Ireland, the United Kingdom and other nations in Europe” (which other nations? – Norway, Denmark?) together and attempts to not only consider them as a bloc but also to infer that the US might be similarly included. Nothing could be further from the truth. Greece and Ireland and the “other nations” in Europe that form the Eurozone run an entirely different monetary system than does the United Kingdom, the other nations in Europe that declined to join the EMU (and do not have currency arrangements fixed to the Euro), and, importantly for the argument, the United States.

When you see someone use this type of conflation you realise that they are either ignorant of the differences and their implications for the conduct for fiscal and monetary policy or they know well and choose to mis-inform the reader for the their own ideological purposes.

The fact is that the fiat currency system that the US or the UK operates leaves them financially at no risk ever of default. These sovereign governments are not financially constrained in any way although they have erected institutional machinery (debt-issuing agencies with prescribed rules) which make it appear as they have constraints. However, these voluntary “constraints” are only of a political nature and could be disassembled at any time (with some political narrative to go with it). They can thus clearly run whatever fiscal stance they like without worrying (ultimately) about what the bond markets might do.

Further, these nations can address external imbalances without having to drive down domestic wages and conditions because their exchange rates float against other currencies.

Finally, the central banks in these nations set whatever interest rate they like and then all other rates in the term structure are so conditioned. The fact that a central bank sets a zero interest rate does not mean that credit is “cheap”. I will address that misconception in a moment for it pervades public debate. All it means is that the private market rates will then be at levels which reflect private assessments of risk. The higher the perceived risk of a particular asset the higher the rate above zero. Cheap in this situation actually means “low perceived risk”.

However, once a country entered the European Monetary Unit (the Eurozone) it surrendered its currency sovereignty (and became financially constrained), its capacity to set interest rates; and its external flexibility (its exchange rate effectively becomes fixed). Some might say that this decision is also voluntary and can be undone just like some of the fiscal rules that non-EMU governments impose on themselves. Technically that is correct but it is one thing for the US government to alter a regulation or law and another for an EMU nation to abandon the Euro and reinstate its own currency.

All Eurozone governments are in the same straitjacket and face insolvency as a consequence.

Anyone with an understanding of macroeconomics and the way the choice of monetary system bears on the opportunity set available to fiscal policy makers would have noted the points I have made above.

But in attempting to expose the flaws in the Republican response, Krugman demonstrates that he also doesn’t get the point. He says the following in response to the quoted section above:

It’s a good story: Europeans dithered on deficits, and that led to crisis. Unfortunately, while that’s more or less true for Greece, it isn’t at all what happened either in Ireland or in Britain, whose experience actually refutes the current Republican narrative.

But then, American conservatives have long had their own private Europe of the imagination – a place of economic stagnation and terrible health care, a collapsing society groaning under the weight of Big Government. The fact that Europe isn’t actually like that – did you know that adults in their prime working years are more likely to be employed in Europe than they are in the United States? – hasn’t deterred them. So we shouldn’t be surprised by similar tall tales about European debt problems.

Krugman then presented the obvious data – viz Ireland and Britain. He thinks the lesson from Ireland for the US is “that balanced budgets won’t protect you from crisis if you don’t effectively regulate your banks”. No, the lesson from Ireland for the US is that a nation that surrenders its fiscal sovereignty cannot respond to a financial crisis in any situation because the bond markets will restrict the capacity of such a government to borrow (in the foreign currency – the Euro).

For the US, the danger of not regulating your banks is independent of the budget position it chooses at any point in time. A balanced budget itself is only sensible if the nation is running an external surplus sufficient to allow the private domestic sector to save without impinging on overall spending growth and maintaining real output growth.

The further caveat I would put on that statement is that the government must also be happy with the mix of private and public output. If they assess that the public output is insufficient then a balanced budget in these circumstances would not be desirable. But that latter consideration is of a political rather than economic nature.

Krugman then says the lesson from Britain is that “slashing government spending in the face of a depressed economy” actually damages growth despite what the conservatives have claimed. The evidence from last week is becoming increasingly clear on that.

So he buys the Republican argument for Greece but not for Ireland and Britain and by implication concludes that “Mr. Ryan … widely portrayed as an intellectual leader within the G.O.P., with special expertise on matters of debt and deficits … doesn’t know the first thing about the debt crises currently in progress is”.

Those in glass houses!

Here is how I would have handled the flawed Ryan logic which is just mindless neo-liberal mythology at its best.

First, the household-government budget conflation myth that drives all mainstream macroeconomic analysis of government policy and always leads it to draw erroneous conclusions. As I have said many times, there is no applicable analogy between the budget of a household and the budget of a sovereign government.

Household spending is always financial constrained as they are users of the currency of issue. Non-government agents in general have to source funds before they can spend – either through earnings, asset sales, prior savings or borrowing.

A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. It neither has to tax or borrow to spend and logically has to spend prior to being able to collect tax revenue or borrow funds.

Second, governments with vastly different monetary systems (EMU versus fiat) cannot be conflated. The US is fully sovereign with respect to its fiscal opportunities and choices. An EMU government does have access to a tax base but its budgetary constraints are akin to those faced by the household in that it has to find funding sources prior to being able to spend.

Third, the ageing population intergenerational budget time bomb myth underpins the Republican response and alleges that the US government, which can always create net financial assets denominated in US dollars, will run out of US dollars because more people will be demanding health care services and pensions future than is the case at present. The simple response to that myth is that the national government (US or any sovereign nation) will always be able to “pay for” its pension obligations or provide first-class health care to all as long as there is a political will to do it and there are real resources available to back the spending.

Fourth, the Republican response also assumes that budget surpluses create national savings which then leads it to claim that governments have to reduce their role in the economy by cutting spending even though there is very high and persistent unemployment and huge spending gaps still present. We are told repeatedly that very difficult decisions and sacrifices have to be made to allow the government to create budget surpluses so that it will have more resources to spend in the future.

In fact, budget surpluses provide no extra spending capacity in the future. A sovereign government has unlimited spending capacity in its own currency. The constraints are never financial unless they are self imposed.

Fifth, the Republican response also trades on what I call the “spend beyond your means myth” which equates budget deficits with excessive spending. But in fact the concept of “means” for a national government is totally inapplicable. It has all the “financial means” that it could ever desire – infinity minus 1 cent. A sovereign government can never spend beyond its “means” although they can spend too much in relation to the real capacity of the economy to absorb that spending via increased output.

With 10 per cent unemployment in the US, the US government faces very little opportunity cost (that is, in real terms) in engaging this labour for productive public sector work. The means are ample.

History only shows that when governments push nominal demand ahead of the growth in the real productive capacity of the economy they push beyond an inflation barrier. Governments have run budget deficits continuously for decades without encountering the types of problems that the conservatives claim are inevitable.

So the Republican response is neo-liberal mythology at its best. Which also suggests that Krugman – by his lack of clarity on what the real issues are in this context – is also entrapped in that destructive mindset.

Aside – the problem with NSW government exposed

Overseas readers might not realise how bad the NSW state government is. It is on its last legs after a series of corrupt and incompetent displays over the last several years including rotating the premier several times.

I think I have discovered the problem.

Yesterday, after the latest (so-called) scandal involving the husband of one of the ministers being arrested by police for purchasing illegal drugs the Premier was asked what her reaction was. She replied that she could sum up her feelings in one word:

I’m furious.

Isn’t that three words abbreviated to two?

Conclusion

Run out of time today …

That is enough for today.

Dear Bill,

Just wanted to pass on to Qld readers if I may, a link to a more ‘real’ appraisal of Cyclone Yasi, approaching the eastern seaboard, than the current bland announcements issued by Qld BOM. It’s a huge system, and if the current ridge of high pressure eases could easily drift further South. Bianca was just a soaking, but this system contains a lot of water.

http://www.youtube.com/user/robcenter1

Cheers,

jrbarch

The Japanese economy is very strange indeed.

I can’t even begin to fathom how the words low unemployment, low interest rates, large budget deficits, low inflation, and low economic growth can be used to describe one economy – they all seem too contradictory. The past 30 years of Japan turns macroeconomics on its head.

Bill, have you written anything about what went wrong in Japan/know of any good pieces? Standard analysis is not too hard to find, however it most often gets stuck up on the idea that Japanese economic woes can be attributed to the government building up excessive debt (whatever else they say after that can be heavily discounted).

A good post, but I wonder about the 10% figure here:

“With 10 per cent unemployment in the US, the US government faces very little opportunity cost (that is, in real terms) in engaging this labour for productive public sector work.”

The better measure for US unemployment “U-6” stands at 17%, and John Williams of Shadowstats.com thinks that even U-6 is not wholly reliable and produces his own estimate: 22%.

If 22% is more accurate, the US unemployment situation is as worse as the Great Depression – this is a sheer disaster.

Bill, you write “An EMU government does have access to a tax base but its budgetary constraints are akin to those faced by the household in that it has to find funding sources prior to being able to spend.” But I have read recently (and I see no reason to doubt it) that the ECB has publicly stated that member nations can issue currency at any time, the ECB just likes to be advised when it happens. In fact, surely MMT would say that in this respect they are the same as any other country, ie when they spend they create currency, when they tax they extinguish it. Could it be that politicians and treasury officials in the nations that have got into trouble were unaware that they could do this? If so, it is another example of self-imposed constraints causing difficulties.

Alex,

I think you are referring to an article by the Independent (?) which said that the Central Bank of Ireland printed money.

Firstly, it was incorrect – literally. The Irish central bank had just increased its lending to credit institutions in one period and the way it does it just like any other bank – Loans make deposits. No money was “printed”. The lending was collateralized and banks have to provide collateral to the central bank if they need to borrow.

I would imagine that the Irish credit institutions borrowed under the “Marginal Lending Facility” at a rate of 1.75%. The ECB allows banks to borrow in any quantity as long as they provide collateral. The list of collateral is decided by the ECB.

Now, one more important fact is that the NCBs like the Central Bank of Ireland can print as many notes as they wish. This is no problem because the currency notes provided is based on banks’ requirements and this is dependent on the private sector demand.

When an NCB prints currency notes (rather, accomodates the demand for currency notes), the following changes occur:

NCB:

Increase in Assets: Claims on the banking system

Increase in Liabilities: Currency Notes in Circulation

Banks:

Increase in Assets: Currency Notes

Increase in Liabilities: Funds Owed to NCB

(Also banks need to put up additional collateral at the NCB).

Now, moving on to government accounts, the government’s Treasury does not have overdraft at the central bank in the Euro Zone. So under extreme market conditions, they may be forced to default if their auctions on issuance of bonds is not successful. This has nothing to do with “printing money”.

Other nations – sovereign ones – typically have escape hatches if there are extreme market conditions and the markets know this to some extent and hence not face a problem in auctions.

Thanks for that jrbarch.

We’re just a little out of the range of the projected damaging winds but that could easily change if the cyclone shifts course.

And another heavy drenching is the last thing we need here in Queensland.

Isn’t the problem with the Japanese economy is that it is set up on a neoliberal

Bill you make the very important point that under a zero interest rate set up, the commercial lending rate is determined solely by perceived risk as there is no longer any scarcity of money as such. The crucial point is that scarcity of money also no longer becomes a constraining influence on asset bubbles. Japan has fed asset bubbles in the rest of the world. The entry for Lehmans bankcrupcy in wikipeadia says:

“In Japan, banks and insurers announced a combined 249 billion yen ($2.4 billion) in potential losses tied to the collapse of Lehman. Mizuho Trust & Banking Co. cut its profit forecast by more than half, citing 11.8 billion yen in losses on bonds and loans linked to Lehman. The Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa said “Most lending to Lehman Brothers was made by major Japanese banks, and their possible losses seem to be within the levels that can be covered by their profits,” adding “There is no concern that the latest events will threaten the stability of Japan’s financial system.””

Clearly the Japanese banks were able to feed off the whole subprime fraud and lived to demonstrate that, in future such scenarios, banks will also be able to do so with impunity.

Bill et al.,

I have recently been trying to debate with people on the BBC Stephanomics blog, and I was trying to get across the chartalist understanding of where tax revenue goes to when it is paid, and by extension where governmet spending comes from when it is spent – or at least how to explain it to ohers.

I think I have had a flash of brilliance (or not). The way of understanding / explaining this is as follows:

1) Strictly speaking, government and non government accounts do not contain “money” – they contain accounting entries! – the “money” is just an abstraction and hence has no intrinsic value.

2) For government accounts, the kinds of transactions possible do not depend on the prior composition of accounting entries in the account, such that there is no “financial constraint”.

3) For a non government accounts, the kinds of transactions possible depend on the prior composition of accounting entries in the account, and this is called a “financial constraint”. This makes possible the useful analogy that the account “contains” money, and that transactions either “take money out” or “put money into” the account.

4) Both the abstraction called “money”, and the analogy of non government accounts “containing money”, are essential to agents in the non government sector in order to help them comply with their financial constraints.

5) For government accounts, when the government spends “money”, the “money” does not come from anywhere because it never existed – it was just a useful abstraction for the benefit of non government agents, so that they can manage their financial constraints.

6) When the government receives tax revenue, the “money” doesn’t go anywhere because it never existed – it was just a useful abstraction for the benefit of non government agents, so that they can manage their financial constraints.

I wonder if anyone (more qualified than me) here would like to comment on this, disregard it, or refine it.

Kind Regards

Charlie

CharlesJ, Warren Mosler (see the link on Bill’s site) uses the analogy that, for the government, money is like the score on the score board at a sports event. When money is spent or taxed by the government it is created and extinguished just as the scores are on the score board.

stone,

Thanks for the reply – I’m aware of the various analogies as you have stated. I was looking to determine how these analogies map to reality, and understand why people find this difficult. Since writing the above comment it also occurs to me that there is a fundamental difference between mainstream views of money and accounting, and the chartalist view:

In the mainstream view, money is seen as “real” whilst the accounting entries are seen as useful abstractions.

In the chartalist view, the accounting entries are seen as “real”, whilst the “money” is seen as the useful abstraction.

Kind Regards

Charlie

Maybe the simplest view of chartalism is that the monetary system is just like a game of monopoly. The bank never runs out of money (and some one looses all their money late at night)!

“accounting entries are seen as “real”, whilst the “money” is seen as the useful abstraction”

Accounting entries are the data that record transactions involving stuff. Money functions as the unit of account.

It’s really difficult to get one’s head around the fact that money is an idea that facilitates dealing with stuff, like real assets and goods, i.e., money functions as a medium of exchange in settling transactions involving stuff. The illusion is created by cash settlement, in which money seems to be an intermediate commodity, but most final settlement takes place on spreadsheets at the cb via bank accounts, where no “money” ever changes hands physically.

stone: “Bill you make the very important point that under a zero interest rate set up, the commercial lending rate is determined solely by perceived risk as there is no longer any scarcity of money as such. The crucial point is that scarcity of money also no longer becomes a constraining influence on asset bubbles.”

It’s not the stock of money that counts in asset bubbles forming as much as the flow. The flow of money is directed by incentives. The way to direct the flow away from things like asset bubbles forming is to tax away economic rent and return it to the economy more productively, e.g., through education, health care, basic research, infrastructure, etc., as well as to put regulation in place that reforms economically parasitical behavior.

The problem is almost always in the incentives. Taxation needs to be targeted to discourage economic rent and negative externalities and to encourage productive investment and income, which contribute directly to supply and demand, instead of extraction, malinvestment, and other dislocation.

I’ve used the credit card analogy to equate to government spending. People understand that you can spend on a credit card without it being prefunded. They also understand that some people can get credit cards without limit – and therefore it is not unreasonable that a government could get one.

If you then equate taxes as an ‘amazing cashback deal’, you can show how the credit card account works in reality.

The other trick is to say that the government just goes to their bank for a loan and always gets it.

Tom Hickey, I don’t get your assertion that a zero interest rate has no effect on asset bubbles. Participation in asset bubbles is in response to the belief that more money will subsequently join the bubble. A bottomless pool of credit created money with no associated cost means that the bubble has no constraint. Bill seemed to be claiming that even with zero base rates, banks would themselves set commercial lending rates at a rate that thwarted asset bubbles because they would not want to face the risks. The Lehmann’s fiasco shows that Japanese banks gaily leaped into the subprime bubble and emerged intact after the bubble burst. The tragedy is that with modern finance methods to hedge market risks, “reckless” participation in speculative bubbles has a better risk/reward balance than does participating in the genuine risks involved in genuine investments in improving infrastructure, technology, training etc like you describe. On the crudest level, simply selling off a proportion of the holdings of an inflating asset as the price inflates, is enough to make it lucrative to participate in asset bubbles.

I’d prefer a universal asset tax (that also applied to cash) rather than having higher interest rates. I just think it necessary to face up to the problems that arise when there is neither. I wish you would spell out concrete examples of your proposed “economic rent taxes”. In the past you said that an asset tax would lead to capital flight. I’d favor an asset tax that applied equally to any assets of a given nations citizens where ever they were held in the world and whatever form they were in. I’m not advocating an increase in the level of taxation rather a change in the manner of taxation.

“stone”

The evidence I’ve seen suggests that the credit cycle happens regardless of the monetary policy of the government. Interest rates have little effect on it.

There is a paper somewhere that shows the credit cycle through all the forms of the monetary policy we’ve had over the last century and it wobbles up and down in strict rhythm oblivious to the lot of them.

It’s quite scary how little impact policy has had on it.

Neil,

The thing I’m trying to get across to people is why a budget deficit does not matter.

So, I reasoned that they must first be able to comprehend the fact the government account does not store any money.

It then occured to me that actually, a person’s own bank account doesn’t store any money either, it stores account entries.

So what makes the accounting entries in a personal bank account, cause that account to behave “like” a store of money (in a tin shed)?

It is the fact that an ordinary person’s account entries determine what further transactions are possible (“financial constraint”).

The government’s account has no such further constraint.

So the key thing to get across to start to explain the difference perhaps is that NO account stores money, it just stores account entries.

Does that make sense?

Charlie

stone: “I don’t get your assertion that a zero interest rate has no effect on asset bubbles.”

Minsky’s work shows that the financial cycle progresses from stability to instability due to dynamics such as Keynes’s “animal spirits,” not the amount of money or interest rates. The solution is not to try to remove instability. This is part of the dynamic of markets that involve risk. It is impossible to eliminate risk without eliminating the market. However, certain incentives result in predictable consequences, and perverse incentives need to be changed.

In addition, rent-seeking results in parasitic wealth extraction. The way to inhibit rent-seeking is through taxing away economic rent – land rent, monopoly rent, and financial rent. Economic rent is surplus value accruing to any factor above what is required to maintain output. The funds taxed away can be committed to productive use for public purpose through expenditure. Rather than being “redistribution,” it is recycling.

See Michael Hudson, NeoLiberalism and the Counter-Enlightenment (May, 2010).

There are other “perverse” incentives, such as pay and bonus structure that encourages excessive risk-taking without sufficient penalty to discourage this. Absent claw-backs, for example, executives ran control frauds and traders whose incentive was bonuses rather than salary took excessive risks. These are the kinds of things that reforms need to address.

Hm… my understanding was that the Japanese unemployment rates understate the true level of unemployment i.e. if the equivalent US standard or measure was used then unemployment would be doubled – an unemployment rate of 4% (Jap) would mean an unemployment rate of 8% (US).

Dear Spadj (at 2011/02/01 at 8:57)

The OECD publish harmonised unemployment rates as part of their Main Economic Indicators which adjust for different definitions across countries. They last had the Japan unemployment rate at 5.1 per cent and the US at 9.8 per cent.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics also publish international comparisons where foreign-country data are adjusted to U.S. concepts. According to that dataset the Japanese unemployment rate was 4.8 per cent in November 2010 and the US was 9.8 per cent.

There is no truth in the claim that the Japanese unemployment rate is understated relative to the US (or Australian) definition. They have maintained relatively low unemployment throughout the crisis and before.

I know a lot of people try to make out that the data about Japan is falsified (including inflation and interest rate data) but that is because they cannot face the facts that Japan defies (proves wrong) the mainstream macroeconomics. I am not suggesting you in that position.

best wishes

bill

Bill said: “The fact is that the Japanese economy has required significant support from budget deficits over a long period given the relative high propensity to save by the private domestic sector.”

I think there must be a valuable explanation behind the large size of Japan’s public debt, and I have been wanting to figure out details for a while (since I haven’t ever seen it addressed). So why is the Japanese desired non-government savings rate high enough to have generated such a large accumulated stock of financial savings? Perhaps someone can give me a shortcut to some answers, but here are my thoughts…

First it should be noted that the household savings rate in Japan fell from over 15% in the 1980s to under 5% over the last couple decades, and has been quite low in recent years. So alongside a (typical) current account surplus, the high total rate of domestic non-government savings appears to be mostly because of the corporate and/or financial sectors.

One explanation could be a tax code that allows wealth to concentrate among those with a low propensity to spend (e.g., corporations not paying out dividends, since it doesn’t appear to be directly the case with households as measured). But that isn’t showing up in the Gini index (Japan is less concentrated than many countries) though I suppose that could be a statistical issue if for some reason claims on corporate net worth aren’t fully accounted for on household balance sheets.

A second explanation could have to do with the private sector paying down debt, but the government’s debt increase has exceeded the private sector’s debt reduction, plus while it could help explain a high savings rate, deleveraging wouldn’t really explain the large net financial savings (on aggregate) of Japan’s private sector.

A third explanation could be that the aggregate valuation of tangible assets has fallen low enough to motivate a higher amount of savings via financial assets instead. However, I’ve looked at this data, and tangible assets to GDP are simply back to pre-bubble (circa 1985) levels, at actually a higher ratio than in the US. And liabilities of the central bank (as opposed to of the treasury) aren’t abnormally low, so it’s not that people simply hold JGBs in lieu of “money”.

A fourth potential explanation likely has to do with the retirement system. Reading a little about it, that seems like the most probable cause — i.e., a high savings rate via the various pension schemes to “save up” financial assets and support retirements. And I have read that the Japanese government “owes itself” a big chunk (half?) of that ~200% of GDP debt, possibly lending further support to this explanation. So, given knowledge of Japan’s aging demographic profile, it should be possible to project when those total financial savings will start being drawn down rather than added to, thus automatically working to reduce the government deficit (and eventually the total debt??).

There is a way in which the mainstream is [sort of] right to worry about some types of government debts — to the extent that they are predictive of large future downward shifts in the non-government savings rate. However, that effect may be spread out over enough years, and combined with a large enough counter-effect from the automatic stabilizers to not be inflationary… but clearly “toy” scenarios would be easy to construct in which a large retirement wave could be inflationary.

Of course I think Bill is right to focus on current full employment and the need to maximize productivity in the present (rather than sabotage the economy) to support future changes in the dependency ratio. But government debt (savings) as a proxy to estimating future spending power that is potentially in excess of capacity may be why many people want to limit “promises” of future levels of retirement benefits. So they may be working from valid instincts, even if many of their solutions are misguided and harmful.

I know Bill has touched on the topic of social security and other retirement systems before, so my real focus here was just trying to understand WHY a national’s private sector might seek to hold an unusually large stock of net financial savings, and what the implications are for the future. Has anyone seen this detailed before (credibly) for Japan?

CharlesJ: I applaud your efforts. But if you’re trying to say that money doesn’t exist, then you’re messing with basic meanings of words – and I would not be optimistic about your chances of a good hearing from people.

Check out Lerner’s Functional Finance. When a govt has received tax money, there are two conceivable impacts this could have: (1) the govt has more money, (2) the non-govt sector has less money. Now, because govt can print money at will, (1) can’t be relevant as it would be easier to just print it – and in practice, new notes entering circulation are generally newly printed. So the functional relevance of tax is just that the non-govt sector has less money, or purchasing power.

This functional analysis is powerful – and it may go down well with punters too.

The idea of “printing money” is more or less baggage from the days of gold standards and fixed exchange rates.

In modern money economies the “printing of money” has essentially been replaced by mere accounting entries .

Therefore,in my opinion we should try not to associate MMT with printing money because for the majority of people that would be equated with – the failed experiments of Weimar Germany or post war Hungary.

Once the MMT / printing money link is gone the neo-liberals really have nowehere to go.

It’s a little like once the wages fund doctrine was no longer popular it’s collary the Malthusuian population doctrine also disappered.

Unfortunately, over the last 40years or so the neo-liberals have re-introduced this relationship via the governments budget contraint / fiscal consolidation and the Integenerational debate.

cheers.

Alan,

what was the the wages fund doctrine?

Graham

CharlesJ, you said “The thing I’m trying to get across to people is why a budget deficit does not matter.”

One way of looking at the position of government as the sovereign issuer of currency is to point out that the only household in a comparable position is a counterfeiter’s household. Does a counterfeiter need to have more income in order to spend more, or savings to draw on? No. He just fires up the printing press. Government is just a little more subtle in that most of the money it creates is created by authorising entries in bank accounts.

hbl,

The Japanese own Japanese public debt because Japan is a net-exporting nation – therefore offshore holdings of Yen are relatively rare.

Generally the reason money is stockpiled is because there is nothing else better to do with it. If the government is offering X% risk free then that sets the minimum bar for any risk based project.

So it could be argued that the actual issuing of long term nominal government debt at a higher rate than the base rate is actually helping to retard real investment in risk based projects.

CharlesJ,

If a government spends £100 then that causes transactions to bounce around the economy like a stone skipping across a pond. At every stage and amount of that money is removed in tax until finally it is taxed away completely.

So if a government spends £100 and everybody receiving that money spends it immediately, the government will *always* get £100 back in tax instantly.

Therefore for there to be a deficit somebody along that chain hasn’t spent their money – in other words they have saved it.

The deficit is nothing more than a number telling you how much people in that currency zone have added to their savings.

Why do we need to get excited about people’s savings?

hbl: I’ve also been intrigued by the Japanese holding so much Yen. One thing I read was that some Japanese corporations hold massive cash reserves. Apparently some Japanese corporations have larger cash reserves than the entire market value of the company. Perhaps this is a defense against hostile takeovers or to put off flighty short term share holders???? With zero interest rates there is perhaps less problem with having such a cash stockpile. I also read that US corporations started to do much the same thing last year but then off loaded the cash via share buy backs. Possibly US share holders have a different attitude to Japanese ones- US shareholders might be seeking takeovers??? Perhaps holding lots of Yen is seen as a good bet whilst USD is seen as more of a devaluation risk???

Ramanan,

“Other nations – sovereign ones – typically have escape hatches if there are extreme market conditions and the markets know this to some extent and hence not face a problem in auctions.”

Platinum coins, obviously?

Thanks Stone, Neil, Alex, Anders, and Alan Dunn,

I agree with Alan in that referring to printed money (or indeed credit cards) is to take the away attention from the accounting reality and opens MMT up to mindless arguments about historic comparisons – or in the case of credit cards – ideas that government requires credit – even when the underlying analogies might be compelling.

By saying that account entries are real, and these entries only imply (by abstraction) the existence of money – and only to non government account holders, not to the government sector accounts – it answers the question – why doesn’t the Treasury Account store money? – because that particular abstraction is not relevant to government sector accounts overall – the money doesn’t cease to exist – the abstraction just ceases to be relevant perhaps.

I’ll keep thinking.

Kind Regards

Neil Wilson,

The reason I am particularly curious about Japan’s government debt situation is that the numbers we hear (~200% of GDP) are so much higher than any other nations at present. Since MMT reveals that government debt is non-government savings and the size is mostly a preference of the non-government sector, I wondered what is making Japan’s so large. I’m not sure being a net exporting nation explains it.

And to the extent that it is simply more attractive than other investments, the market valuation of those other investments (equities, real estate, etc) should probably be comparably smaller as a ratio to GDP to offset the extra large net financial savings held as liabilities of the government. But I’ve looked at the data and as best I can tell they are not… for example tangible assets (which includes real estate) seem to be valued higher relative to GDP than in the US. And there is still a large stock of private debt/assets.

stone,

That does seem like it could explain at least part of the phenomenon, and could fit within my first category of explanation (of the four I gave). However, I wonder whether corporate balance sheet equity is correspondingly high, or whether corporate cash reserves are obtained via expanded liabilities on the other side of the balance sheet (I read that in the US some of the excess corporate cash was due to precautionary borrowing). Such a situation wouldn’t reflect NET financial assets being high. And, it’s JGB holdings by the private sector that are especially high, not just yen deposits/currency. But the fact does seem to be that for whatever reasons, corporations do hold a lot of financial assets, so the question is “why?” Perhaps it’s the reasons you mention, or perhaps they are savings destined for pensioners (my primary guess still), or perhaps something else…

anon,

He he. Maybe.

If the need arises, the markets may start saying “they can mint the money, can’t they?” instead of saying, “they can print the money can’t they?”

hbl,

You raise an important point and I agree with you that exports do not explain it. In since exports add to income, “the contribution from exports” to the public debt is negative. (That’s a careless way of putting it).

What I mean is that if the Net private saving is typically in its habitat of a positive percentage of gdp and the current account is positive, then the deficit is lower than the case where there is no current account. NPS=DEF+CAB and hence DEF = NPS – CAB. Closing stock of public debt is the opening stock plus DEF. And you would expect the public debt to be lower than otherwise.

In fact, net exports by Japan make this question even more interesting.

Seems like one has to go into a lot of details to find the answer to this question. Its one thing to say that the propensity to consume changed etc, quite different to go into details.

Ramanan said: “Seems like one has to go into a lot of details to find the answer to this question.”

I’ve actually looked at Japan’s national accounts data to try to find answers, but unfortunately the granularity wasn’t sufficient for me to draw any solid conclusions. But glancing over some summaries of Japan’s retirement system structure seemed to anecdotally support the “savings for retirement” thesis, though I haven’t found the data to quantify it.

And because I didn’t explicitly state it before (though most people would be aware of it already)… the reason this matters is Japan is one of the “oldest” nations demographically. It will be a big test of theories on what will happen to inflation/capacity/etc as the dependency ratio changes to include less workers and more people drawing down savings. Qualitatively, I’ve seen Bill discuss this stuff before (not specifically regarding Japan), but I’ve never seen him or others attempt to quantify how it may play out. Of course doing so would not be trivial. But my larger point was how it *may* relate with a kernel of validity to fears about the ultimate consequences of Japan’s large government debt. I say “kernel” only because I very much doubt it will play out calamitously. And of course I know the fears are based on the wrong economic understanding and lead people to suggest mostly damaging remedies.

Dear All

One of the clues to Japan’s very high saving propensity given its net exports (and hence the need to have large public deficits to maintain growth) is that there is no pension system like we know it in places like Australia, US, UK and/or European nations. So people are very literally saving for their retirement.

On top of that is the cultural leaning towards saving. An interesting thing about Japan is that this cultural tendency is evaporating in the younger generations who are more “western” in attitudes. Things will change.

best wishes

bill

hbl, my understanding (of something on the web by Jean-Marie Eveillard) was that many Japanese corporations had huge cash reserves that were not offset by debts and that they had built up as retained profits. I see what you mean about US corporations getting lots of cash via borrowing whilst borrowing was cheap so as to tide them over for the future and that that is unlike having net cash reserves.

Perhaps if Yen and JGB pile up due to deficits, then it is not so much a case of the people having a propensity to save as of what else is going to happen to all that Yen and JGB. Basically the turnover rate of the Yen drops and drops and that counteracts the build up so that deflation is maintained. With deflation and a strengthening Yen, real interest rates are pretty good even with zero short term rates and 0.6% rates for 10year JGB.

Bill,

Thanks for sharing that… the detail on pensions seems to confirm my guess.

With respect to cultural leaning toward saving, if you look at charts of Japan’s household savings rate it has been falling steadily since 1975. In 1990 when the government debt was about 60% of GDP, the household savings rate was down to the 10-15% range. While the household savings rate fell steadily to under 5% since then, government debt has reached around 200% of GDP. So given how much the rate of household savings has been slowing it didn’t seem likely that the recent lower household savings rate alone could have accounted for such a large increase in government debt. But I suppose in theory it could have (since all the years are degrees of *positive* savings). And some of the savings perhaps aren’t accounted for on the household balance sheets (i.e., perhaps instead on pension company ones).

Usually when people call Japan a “nation of savers” and emphasize the comparison to the US, I don’t think they realize how close the two household savings rates have already become in recent years. But I do see that it is a bit more complicated.

Is the ratio of government debt to private debt the key difference between Japan and “western” economies such as UK? Sorry if this is way to elementary but I’m struggling to grasp it all. Is the hope that increasing the amount of government debt will reduce the amount of private debt? Bill’s comment about young Japanese not saving makes me worried that such a happy outcome may not pan out. If the “western way” is to avoid holding cash and to instead buy non-cash stores of value with any excess, then there will be inflation of any such stores of value. The huge danger is when such stores of value coincide with something of actual worth (eg wheat). Even inflation of share prices beyond the point where earnings are what makes shares attractive is in my opinion very damaging as it unhinges the private sector from acting in a way that meets peoples needs.

hbl – the massive private surplus for me has to reflect an anxiety about future prospects vs the beginning of period balance sheet position. Data on household savings indicates that they aren’t coming out of a debt binge, like UK and US consumers (albeit that they have retirement issues as Bill highlights).

This suggests that they are less than half of the story. In other words – by elimination, the main issue has to be corporate balance sheet distress.

Graham.

The wages fund doctrine assumes that wage = capital / population.

Capital is assumed to be fixed and population is assumed to be an endogenous variable.

Thus, as population increases the populations ability to maintain subsistence decreases.

The solution to the problem [sic] was “moral restraint.

In neo-liberal parlance moral restraint has been replaced with “fiscal consolidation” and the wages fund by the “government budget constraint.

cheers.

Just wanted to say thanks to Bill & all for an extraordinarily interesting & informative blog.

ok carry on 🙂