Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Fiscal surplus by 2017-18? A mindless goal guaranteed to cause havoc and fail

Its sad when politicians lie just to get political points as they face declining popularity. We saw last week that the Australian Prime Minister started attacking indigenous Australians for living in areas that they have occupied, one way or another, for somewhere up to 80,000 years. He claimed these settlements were “lifestyle” choices and people could no longer expect government support if they wanted to indulge in such choices. 80,000 years for a culture that has a deep connection with the ‘land’ is quite story compared to the Anglo settlement in Australia of 226 years for a culture that connects via iPhones! The PM was playing into the hands of the racist Australians who think the indigenous population here are skivers and drunks and should get no state support. They ignore that this cohort is one of the most disadvantaged peoples of the World. In the last few days, the PM has been lying about the state of government finances and pledging to that “the government will have the budget back in balance within five years”. There was no mention of what this might imply for the real economy. I am surprised that the conservatives haven’t learned from the previous Labor Government who made continual promises of surpluses but failed each time – largely because they didn’t understand that they cannot control the fiscal outcomes no matter how hard they try. And when they do try and run against the spending desires of the non-government sector, they just cause havoc and damage and fail to achieve their goals anyway. Stupid is not the word for these sorts of promises.

The Fairfax newspapers carried a story this morning (March 18, 2015) – Tony Abbott claims Australia was heading for a ‘Greek-style future’.

It followed the Prime Minister’s claims yesterday (March 17, 2015) that “the government will have the budget back in balance within five years” , which were reported in this article – Tony Abbott’s promise to balance budget in five years raises prospect of new cuts.

Yesterday, it was the near impossible. Today the incredible. Australia is to cede its currency sovereignty and become like Greece. Who are we ceding it to?

The conservatives are not alone in this folly. The previous Labor government, which was defeated in September 2014, arguably starting running off the rails when it began to promise fiscal surpluses as a stand-alone goal, without any contextual justification, and failed (badly) to achieve them.

The previous treasurer Wayne Swan while in that position (2007-2014) promised that the Labor government would deliver surpluses on more than 500 occasions.

Recall his first fiscal statement delivered on May 13, 2008. In his – Budget Speech 2008-09 – Swan said:

We are budgeting for a surplus of $21.7 billion in 2008‑09, 1.8 per cent of GDP, the largest budget surplus as a share of GDP in nearly a decade.

His justification was that:

… we need a strong surplus to anchor a strong economy; to do our bit to ease inflationary pressures in the economy; to build a buffer against international turbulence; and so we can fund ongoing long term investment in the ports, roads, railways, hospitals, universities and vocational education we need, to deliver growth with low inflation into the future.

All the talk was about quelling inflation which was stable and doing nothing at the time.

You can see the flawed reasoning – that a fiscal surplus was needed to ‘store’ up money so that they can spend it on public infrastructure.

Yet they were also committed to paying down public debt. So where, even in their own logic, was the ‘money’ going to come from?

Of course, the whole presentation was erroneous and reflects the fiscal myths that pervade the neo-liberal era.

Please read the following introductory suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for basic Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) concepts.

And – Budget deficit basics.

And – Deficits are our saving

And – Budget surpluses are not national saving

Fiscal surpluses are not public saving.

The often-heard argument that fiscal surpluses represent ‘public saving’, which can be used to fund future public expenditure, is erroneous at the most elemental level.

Public surpluses do not create a cache of money that can be spent later.

The Australian government has cash operating accounts – to ensure that they can spend (G) on a daily basis and receive daily receipts (T). The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) “provides a facility to the Australian Government that is used to manage a group of bank accounts, known as the Official Public Account (OPA) Group, the aggregate balance of which represents the Government’s daily cash position.” (see details here).

When the Federal government spends it debits these accounts and credits various bank accounts within the commercial banking system. Deposits thus show up in a number of commercial banks as a reflection of the spending. It may issue a cheque and post it to someone in the private sector whereupon that person will deposit the cheque at their bank. It is the same effect as if it had have all been done electronically.

All federal spending happens like this. You will note that:

- Governments do not spend by ‘printing money’. They spend by creating deposits in the private banking system. Clearly, some currency is in circulation which is ‘printed’ but that is a separate process from the daily spending and taxing flows;

- There has been no mention of where they get the credits and debits come from! The short answer is that the spending comes from no-where. Suffice to say that the Federal government, as the monopoly issuer of its own currency is not revenue-constrained. This means it does not have to ‘finance’ its spending unlike a household, which uses the fiat currency; and

- Any coincident issuing of government debt (bonds) has nothing to do with ‘financing’ the government spending.

So the Australian government spends by crediting a reserve account in the private banking system (via some central bank operation). That spending doesn’t ‘come from anywhere’, as, for example, gold coins would have had to come from somewhere. It is accounted for but that is a different issue.

Likewise, payments to government reduce reserve balances. Those payments do not ‘go anywhere’ but are merely accounted for.

In an accounting sense, when there is a fiscal surplus then private wealth is destroyed. There is no storage shed where surpluses are put to be used later. When a surplus is run, the purchasing power embodied in them is destroyed forever.

The fiscal surplus may be applied to running down debt (that is, forcing the private sector to liquidate its wealth to get cash) but this strategy does not provide future savings.

Say the sovereign government ran a $15 billion surplus in the last financial year. It could then purchase that amount of financial assets in the domestic and international capital markets. But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the budget would break even. In these situations, the public debate should be focused on whether this is the best use of public funds. It would be hard to justify this sort of spending when basic infrastructure provision and employment creation has been ignored for many years by neo-liberal governments.

The alternative when a surplus is generated is to destroy liquidity (debiting reserve accounts) which is deflationary. The weaker demand conditions would force producers to reduce output and layoff workers with rapid increases in joblessness. Investment irreversibilities driven by uncertainty of future demand conditions then retard capacity growth and prolong the downturn.

The point is that the currency-issuing government can always purchase anything that is for sale in the currency that it issues. There is never a question about that capacity.

So a fiscal surplus or deficit today, provides no less or more scope for public spending tomorrow. That capacity is infinite financially and constrained by the real goods and services that are for sale in that currency.

Treasurers like Swan and now Hockey can get away with the fiscal myths because the general population is financially illiterate. There was an interesting article in the UK Guardian earlier this week (March 16, 2015) – Lack of financial literacy among voters is a ‘threat to democracy’ – which reported on survey results from a study conducted by students at Manchester University.

In a multiple choice style quick around 50 per cent of respondents didn’t even know what a fiscal deficit was.

When Swan was promising the biggest fiscal surpluses in a decade he was clearly not cogniscant of what was about to happen in the World economy.

Even in his Fiscal Speech to Parliament he acknowledged that “Weaker global growth and the effects of monetary policy are slowing our economy” yet failed to connect his ambitons for fiscal surpluses with that reality.

And then along came the GFC.

How many fiscal surpluses did Swan deliver? None.

Was that a failure? Absolutely not.

What was the problem? Promising them and then believing his own rhetoric and cutting government spending at a time when the Australian economy could ill-afford the contraction in public spending.

Result? The initial recovery from the GFC spawned by the deliberate increase in net public spending via two stimulus packages was prematurely undermined and the Australian economy is stuck in a low growth malaise with rising unemployment.

That government eventually became so discredited because it keep promising to achieve fiscal surpluses and each year the fiscal deficit would rise.

It was obvious that the attempt to achieve the surplus led to such a fiscal consolidation in 2012 that the economy began to tank and tax revenue fell sharply below expectations.

The damage caused by those cuts were compounded by the drop in our terms of trade (commodity prices) which has further undermined the tax base of the government and led to increased fiscal deficits.

And then we come to today’s politicians who are still intent on perpetuating these neo-liberal myths about deficits.

Yesterday, the Prime Minister claimed that if reelected next year, his Government would deliver a fiscal surplus within five years.

The question he avoided was how could he guarantee that promise?

This Government has already been burned by trying to promise a specific fiscal balance (surplus) when such an outcome is beyond its control.

The current Treasurer (in his role as Shadow Treasurer at the time) delivered a – Post Budget Address – to the National Press Club on May 16, 2012, in reply to the fiscal statement just delivered by the then Labor Government.

The soon to be Treasurer Joe Hockey said:

… we will achieve a surplus in our first year in office and we will achieve a surplus for every year of our first term.

Our surpluses will be real.

His first actual – Fiscal Statement – as Treasurer delivered on May 13, 2014 projected that the fiscal deficit of $A49.9 billion (3.1 per cent of GDP) in 2013-14 would turn into a near balance ($2.7 billion or 0.2 per cent of GDP) by 2017-18.

He also claimed that federal debt would be reduced to 18.7 per cent of GDP by 2017-18.

The wheels started falling off those estimates almost immediately and by the time the Government delivered its – Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook – on December 15, 2014 (just 7 months later), the 2017-18 fiscal balance was projected to be $A11.5 billion or 0.6 per cent of GDP.

Further, the GDP estimates built-in to those estimates were too optimistic as subsequent events have shown.

In this blog – Crikey, why is it is honourable to deliberately increase unemployment? – I analysed the latest – Australian Government Monthly Financial Statements December 2014 – which allowed us to see the full fiscal accounting data for 2014.

Far from overseeing a declining public debt environment, the current Treasurer has been in charge while public debt and the fiscal deficit (the two are linked under current arrangements) have risen.

Since the GFC the trends have been obvious.

The previous federal government (Australian Labor Party) was in office from December 2007 until September 17, 2013. The current conservative government took office in September 2013.

The previous government had to deal with the GFC and initiated two large stimulus packages in 2008, which ultimately showed up as a rise in net debt, given the unnecessary practice of issuing debt to the private sector to match the fiscal deficit.

The change in public debt is just an accounting record of the fiscal deficits in the respective periods under the unnecessary institutional rules that require the government to match its fiscal deficits with private debt issuance.

The fiscal deficit rose for two reasons:

1. The GFC triggered the fiscal automatic stabilisers and tax revenue declined sharply and welfare payments rose. That cyclical effect, which is built into the fiscal balance outcome would have pushed the government deficit up even if the government had sat on its hands and let the crisis unfold.

The cyclical effect tells us that the final fiscal outcome is typically driven by the spending (and saving) decisions of the non-government sector (external sector, households and firms). It is not an outcome that the government can particularly control or target and nor should it.

It reflects the state of the real economy which is where the policy targets should be expressed – that is, high employment growth, sustainable output growth and the like. The fiscal balance will just act as a measuring gauge for what is going on in the real economy and as no intrinsic interest or importance in its own right.

2. The discretionary fiscal stimulus packages manifested in the form of increased spending, mostly on infrastructure.

The ALP government then went crazy and bent to the pressure from the conservatives regarding the deficit and the associated build up of net debt. The sky was about to fall in – or so it was claimed.

So by 2013 it had cut hard into public spending and the result was a decline in net debt. The problem with that strategy was that the public spending cuts embodied in their pursuit of austerity led to a slowing economy and rising unemployment.

By the time the conservatives took office on September 18, 2013, the economy was in a poor state with real growth well below trend and declining fast, inflation falling, employment growth below the growth of the labour force and unemployment rising.

The fiscal manifestation of that real disaster (rising unemployment etc) was further declining tax revenue for the Commonwealth government and a failure to stem welfare payments despite their vicious efforts to penalise those on income support.

The result was obvious – the fiscal deficit has risen and with it net debt has risen much more in the last year than in the previous two years.

The current government could have accepted that it inherited an ailing economy as a result of the obsession of the last government with pursuing fiscal surpluses at a time that the external sector was draining overall spending and private domestic spending was insufficient to support even a trend rate of growth.

But it had demonised the previous government and during the 2013 federal election campaign had relentlessly told the public that there was a fiscal and debt emergency, which required immediate treatment. If left untreated interest rates and inflation would explode, the goverment would run out of money and the rating agencies would cut our AAA rating.

All nonsense of course but it was a smokescreen to allow them to engage in their ideologically-motivated cuts in public net spending, which backfired because the private economy was slowing fast.

So the fact that the net debt rose in 2014 is highly political – it shows that the government was lying when in opposition about the debt emergency (nothing much has happened – interest rates have declined and inflation is falling).

It also shows that the government is incompetent by its own twisted and wrongful logic because it promised to significantly cut the fiscal deficit and net debt.

It hasn’t succeeded – (thank goodness) – because the austerity-oriented policy mix has further undermined real growth and tax revenue. I say thank goodness because the situation would have been worse had they been able to cut as hard as they wanted to. They have been held up somewhat by a hostile Senate.

The tax revenue has also fallen because of the decline in our terms of trade. In the latest – National Accounts – we saw how they have declined by 10.8 per cent over the year to the December-quarter 2014.

If you examine movements in – Commodity Prices – you will see that since September 2013 (when the current government took office), that commodity prices have fallen by 16.3 per cent in Australian dollar terms (27.9 per cent in US dollar terms).

That is a sizeable shift for the economy’s income earning capacity and hence taxation revenue.

The point is that the Government can control some of the parameters that influence the fiscal outcome (like some of its own spending and tax structures) but, ultimately, the final fiscal outcome is dependent on the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector.

Why? Because those decisions are crucial determinants of national income growth and employment growth and the fiscal balance is sensitive to that growth.

The other issue is that when governments try to buck the spending decisions of the non-government sector and pursue fiscal surpluses at times when non-government spending is subdued, the outcome is always to reduce economic growth and national income growth.

The result is obvious. Unemployment rises, welfare spending rises and tax revenue falls.

This is why the fiscal deficit has been rising beyond the estimates over the last several years. The pursuit of surpluses actually undermines their achievement.

Which is why fiscal rules that are without a real economy context are likely to lead to damaging outcomes and not achieve their aims.

Fiscal policy always has to be linked to real policy goals such as full employment. There is never any sense in setting fiscal balance targets in isolation.

The previous Labor government failed. The current Government is failing. It makes no sense to pursue a fiscal target for its own sake.

And then we had the Prime Minister yesterday telling us about Greece.

He said that Australia:

Under the former Labor government we were heading to a Greek-style economic future.

The comments have been condemmed in the press today but for the wrong reasons.

There have been comparisons with Greece’s 164 per cent of GDP debnt in 2012 compared to Australia’s 42 per cent. And Greece’s 26 per cent unemployment compared to Australia’s 6 per cent.

The Labor spokesperson Chris Bowen has been dishing out the fiscal myths as he attacks the PM.

But all those comparisons are missing the point.

The point is clear:

1. Australia issues its own currency, Greece does not.

2. The Australian government can never run out of Australian dollars, the Greek government can easily run out of Euros.

3. The Australian government does not need to issue debt to spend more than it takes back in taxes, the Greek government always has to issue debt in such situations.

Currency sovereignty means that the Australian government can always meet its liabilities in Australian dollars and can always guarantee full employment through appropriately scaled government spending.

The Greek government cannot issue such guarantees while it is a ‘state’ of the Eurozone, with currency sovereignty.

The Labor government should be leading the re-education program to ensure that people who vote understand these issues and are not beguiled by the lies that ignorance and self-serving politicians tell to shore up political support.

There are some facts that the public need to understand.

Fact 1 – Continuous fiscal deficits are normal

The obsession with “we will get back into surplus as soon as possible” denies history.

There is the notion in the public sphere, promoted by a few decades of neo-liberal hectoring, that continuous deficits are somehow abnormal or bad. The public now think – that responsible governments ‘balance their budgets over the business cycle’.

Where did anyone get that idea from other than ideologically-laden mainstream macroeconomic textbooks that our students forced to use?

The reality is that fiscal deficits have been the norm over any of the successive business cycles. There is no evidence that Australian governments ‘balance budgets’ over the cycle.

The further evidence is that as the neo-liberal persuasion has become dominant in macroeconomic policy, Australian governments have attempted to run discretionary surpluses. The outcomes of this behaviour have not been good and overall this period (since around the mid-1970s) have been associated with lower average real GDP growth and more than double the average unemployment rate.

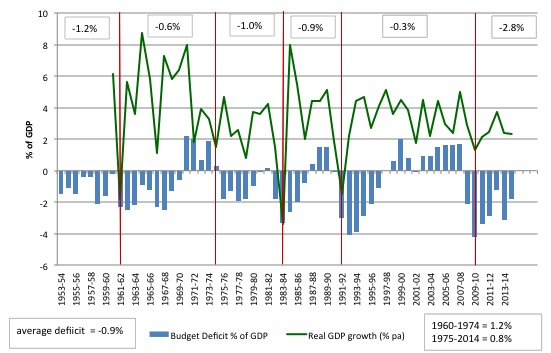

The following graph is based on historical data which is explained in this blog – Australian fiscal statement – attacks the weakest and will undermine prosperity overall.

The graph below is a reasonably reliable depiction to the history of Federal government fiscal outcomes outcomes over the period – 1953-54 to 2013-14.

The columns show the Federal fiscal balance as a per cent of GDP (negative denoting deficits) while the green line shows the average quarterly real GDP growth (averaged over the financial year at June).

The red vertical lines denote the trough of the respective business cycles. So the real GDP growth line approximates where in the year the negative real GDP growth manifested. But for our purposes it is near enough.

The upper numbers in boxes are the average deficits over each cyclical periods. The average deficit over the whole period was 0.8 per cent of GDP. The average real GDP growth per quarter from 1959-60 was 1.2 per cent and after 1975 this dropped to 0.8 per cent. The unemployment rate averaged below 2.0 per cent in the pre-1975 period and averaged around 5.5 per cent after 1975.

The 1975 Budget was a historical document because it was the first time the Federal Government began to articulate the neo-liberal argument that fiscal deficits should be avoided if possible and surpluses were the exemplar of fiscal responsibility.

Please read my blog – Tracing the origins of the fetish against deficits in Australia – for more discussion on this point.

Some points to note:

1. One the rare occasions the fiscal balance was pushed into surplus (usually by discretionary intent of the Government) a major recession followed soon after. The association is not coincidental and reflects the cumulative impact of the fiscal drag (that is, the surpluses draining private purchasing power) interacting with collapsing private spending.

2. There is no notion over this period that the fiscal outcome was ‘balanced’ over the business cycle. The historical reality is that the federal government is usually in deficit. If I had have assembled more historical data which is available in the individual budget papers going back to the 1930s then it would have just reinforced the reality that surpluses have been rare in our history independent of the monetary system operating (the old convertible system or today’s non-convertible system).

3. The Australian federal government ran fiscal deficits of varying sizes in 75 per cent of the years between 1953-54 and 2014-15 (46 out of the 61 years).

4. The fact that the conservatives were able to run surpluses for 10 out of 11 consecutive years (1996 to 2007) is often held out as a practical demonstration of how a disciplined government can run down public debt and provide scope for private activity. The reality is that during this period we have witnessed a record build-up in private indebtedness (see below).

The only way the economy was able to grow relatively strongly during this period was that private spending financed by increasing credit growth was strong. This growth strategy was never going to be sustainable and the financial crisis was the manifestation of that credit binge exploding and bringing the real economy down with it.

A recent report in the Fairfax press (March 16, 2015) – Australian households awash with debt: Barclays – tells us that:

Australian households are the most indebted in the world

This is no surprise. With the attempt at achieving surpluses leading to a slowdown in the Australian economy (exacerbating other non-fiscal negative influences on growth), household incomes are being squeezed again and with real wages growth flat, credit is the way households maintain their spending.

5. The higher deficits in the recent period is testament to the fiscal stimulus package and, perversely, the fiscal contraction that followed. Remember this is a ratio of the fiscal balance to GDP. So if the numerator (fiscal balance) goes up faster than the denominator (GDP) then the ratio rises and vice-versa. But if the denominator falls more quickly than the numerator (at a time of fiscal austerity) the ratio can also rise. The previous government cut hard in their second last fiscal statement and that caused the economy to slow.

Fact 2 GDP is well below trend

The second fact is that real GDP growth is still well below its recent trend. This means that overall spending is weak and unable to fully absorb the productive resources available.

It is not a time that a government should be pursuing any contraction in its fiscal stance.

Fact 3 Labour Underutilisation is high and rising

The Australian economy is far from being close to full employment.

The ABS Broad labour underutilisation series, which simply adds the official unemployment rate to the underemployment rate, is currently at 14.9 per cent and has been rising as the economy slowed after the retrenchment of the fiscal stimulus package.

It has risen by 1.4 per cent since the Treasurer delivered his May 2014 Fiscal Statement, which implemented public spending cuts.

Conclusion

The Prime Minister will only be able to achieve a fiscal surplus by 2017-18 under the following conditions:

1. There is a massive boom in non-government spending. Probability – highly unlikely.

2. They cut spending heavily and raise taxes such that the discretionary impact on the fiscal balance runs faster than the automatic stabiliser effect (the loss of tax revenue as the economy tanks) which would be pushing the deficit up.

The result in that case would a disastrous recession with double-digit unemployment and increased poverty. They would not survive the next election if they attempted that plan.

In the first scenario, the private sector debt levels would rise and become so precarious that eventually the house of cards would collapse (as it did during the GFC) and the fiscal balance would shoot upwards (higher deficits).

Either way, trying to buck the reality of the situation is not good policy.

The Government should be concerned with getting unemployment down, funding education properly and ensuring our future productivity is enhanced.

None of that will be achieved with fiscal austerity. It is a mindless goal that is guaranteed to cause havoc – and fail.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill,

Did you see the ABC program “Making Australia Great – Inside our Longest Boom” last night ?

The program was an absolute disgrace and perpetuated all the neo-liberal economic myths anyone could care to name.

The journalist responsible was George Megalogenis and the sooner he retires from writing about economic matters the better.

The Reserve Bank Website states that it provides the government with

Obviously there is no need for this to be limited i.e. for the government to issue bonds to cover the fiscal deficit, but I am curious as to what the strictly limited means. Is it just an empty phrase, or is there actually a limit in place?

“Strictly limited” means an amount which is greater than the dollar amount of the phone bills Peter Reiths son was accumulating at the governments expense in the late 1990’s.

“The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) “provides a facility to the Australian Government that is used to manage a group of bank accounts, known as the Official Public Account (OPA) Group, the aggregate balance of which represents the Government’s daily cash position.” (see details here”

the link you provided does not exist anymore.

cheers

new link (pertaining to my question too) is here

Hi Bill ,

Is there a law in the RBA act or elsewhere that says the RBA or the Office of Financial Management must issue bonds to finance government deficits or is it just a regulation?

I was wondering how hard would it be for a government to change this ie would it need legislation that would have to pass both houses?

Abbott has a mouth a great deal larger than his brain,and not just in matters economic.

The sooner that clown departs the scene the better. No doubt to be replaced by another clown in a slightly different costume.

I too watched ‘Making Australia Great – with George Megalogenis’ last night, and was also appalled by the incredible level of ignorance featured. I thought it was all about making George ‘great’ (by rubbing shoulders with other great like-minded vsp’s and repeating wise-old neolib mantras)! You can leave a comment here if you think its worthwhile!

Dear JrBarch and Alan Dunn

If you have read his journalistic pieces on the economy you would have been forewarned not to watch the program. You obviously found at the hard way.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill

The Canadian government ran surpluses when Paul Martin was Minister of Finance. As a result, may people were heaping praise on Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and calling Paul Martin the greatest Minister of Finance in Canadian history. The surpluses seem to have worked because there were very vigorous exports. The current Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, also thinks that balanced budgets are the quintessence of good governance.

Your colleague Heiner Flassbeck at http://www.flassbeck-economics.de started a series on banking. He takes the same position as you, namely that banks don’t need deposits to make loans. “Die Darlehensvergabe setzt nicht voraus, dass Banken vorab über Geld verfügen, vielmehr wird im Prozess der Darlehensvergabe Geld geschaffen”.

Regards. James

“namely that banks don’t need deposits to make loans”

Banks don’t need deposits *ahead of time* to make loans. The two main banking processes (lending and funding) are asynchronous in time and are linked only by the price of money.

The problem is static analysis of business processes by people who think undergraduate mathematics are the state of the art in analysis.

Anybody with half a brain should realise that to get the best ROI you are best to push your sales (loans) before you increase your costs (funding).

Do these 80,000 years of “lifestyle” choices include a substantial period of ownership of the land ended by a brief period when those land rights were taken away? What is it with those of British heritage that causes them to believe no one’s land rights are superior to their own feeble claims of same?

I don’t like this phrasing, as it implies that there is a reason to compare revenue of the currency issuer with its spending (thereby calculating deficits or surpluses) when there is not. To me, this just plays into the neoliberal framing that say there is a reason, and this results in unnecessary confusion. If the concept of comparing these aggregates is incorrect, avoiding framing suggesting otherwise must be avoided.

In my view, money invested in bonds of the issuer has simply gotten “tired” (it falls out of use in the currency base (currency + reserves) as no acceptable non-risk investments for it can be found), and must be replaced in that currency base in order to maintain that base at an adequate level to fund growth activities.

Bill,

In previous blogs you’ve outlined how when Australia ran a surplus (in the Howard era I think?), the corporates that rely on Government debt to anchor their investments started screaming for more debt to be issued… and the Government duly obliged.

Today I found the first article I’ve encountered written by a Wall Street type publically putting essentially that same case forward:

Coming from a trader you probably wouldn’t be surprised the piece contains plenty of neoliberal stuff but for reasons of self-interest, he knows he wants more public spending and debt issued, not less.

Similarly, a professor Mark Blyth went before the US Senate Budget Committee recently and busted a few myths around national debt, deficits etc.

Hoping for more voices saying similar things!

Artheur Laffer of the Laffer Curve is in town speaking to the IPA. Is this likely to influence the next budget fiasco?

hi neil and others,

excellent article re banking

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/…/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

Hi Bill

Thanks for another great post. You explain: “that the conservatives haven’t learned from the previous Labor Government who made continual promises of surpluses but failed each time – largely because they didn’t understand that they cannot control the fiscal outcomes no matter how hard they try.”

I just cannot believe that they don’t know what they are doing. In Hockey’s case, I think he and his mates are bleeding the states for the purpose of presenting privatisation as a last option. The shortage of money forces us to seemingly drastic solutions. Yet, no-one asks “Where does money come from?”. That seems to me a key question and your appreciation of currency sovereignty is the answer.

I am finally coming to the conclusion that Randall Wray presents in the first of the Modern Money and Public Purpose lectures (Samuelson to Blaug slide). That it really is a conspiracy to keep us ignorant that both major parties are involved in. If we understood Government’s capacity to influence the economy our expectations would run rampant. That cannot be. We would then understand that our problems are not shortage of money but caused by Government decisions.

The blyth link given above is a good example of how to discuss this subject in clear, non-technical language.

A major problem with MMM is that underlying concepts relating to fiscal matters are hard to understand from a layman’s perspective. The arguments tend to be riddled with untested or unexplained assumptions. Consequently, I don’t think the case is argued all that successfully.

That’s why it appears so puzzling to MMM proponents that successive secretaries of the treasury don’t seem to agree with many of the premises of modern monetary theory, even such a simple one as that deficits are not intrinsically bad. The reason may be that the arguments presented on behalf of MMM are made too opaque by lots of repeated and circular half-arguments containing ellipses in the logic. With Bill’s work, which I basically agree with, there is the great effort required to cross-reference the numerous postings to build up any kind of coherent thesis.

To get a handle on the subject requires a lot of stitching together of seperate mini-threads, most of which need sub-threads themselves to be substantiated. In the realm of blogging and posting, this involves simply far too much effort, and so a path of least resistence is followed, whereby a lot of the arguments tend to be taken for granted or glossed over.

Coming at this subject from a more intuitive viewpoint might yield better results for the non-specialist. For example, to counter the deficit-is-bad argument, one might posit a world in which no country at all had a deficit. And by extension, no individual , or no corporation or business either. A world entirely free of deficit, and by extension, debt. Where would we be?

I think the non-specialiist could more easily imagine under such a scenario that the world would be somewhere back in a pre-industrial revolution era, perhaps in the fourteenth or fifteenth century.

Warren, unfortunately, whether it’s a lack of understanding or ulterior motive, the outcome is the same. Keep fighting the fight.

hi warren,

i come across a lot of federal polies and their advisors, and i can tell you they dont sully their elevated minds with the facts 😉

hey benedict,

for the british, it was the british navy and then later the machine gun, until the locals go their hands on the same bit of kit and started shooting back 😉

our locals didnt manage to get their hands on the kit.

To David and Mahaish

David, thanks for the encouragement. This debate in my bones and as you suggest I will keep at it.

Mahaish, I too have met many politicians and advisers who seem to have no concept of what Bill is putting across. I used to work with one of Australia’s leading insurers in report management and made a habit of asking actuaries, auditors and accountants “Where does money come from?” and their answers were astounding. I am reluctantly willing to accept that anyone from below ministerial level may be fuzzy on the subject, however, I cannot accept that someone like Chris Bowen doesn’t get it. Maybe Jenny Macklin doesn’t but Tony Burke must. From this point I wonder why Chris Bowen will sit on programmes like QandA, 7.30 or Insiders and allow himself to be battered about over the state of the budget when he left office. I can only assume he is working from a rule book that says don’t let in on the key reasons for calling for a surplus. Constraining our expectations is more important than winning the argument or achieving anything. They must remain in control.

Andi,

It seems to be government policy to issue debt regardless of the fiscal position.

Here’s a footnote to a speech by Guy Debelle of the RBA a couple of years ago.

http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2014/sp-ag-150414.html

“The Australian government announced in its 2011/12 Budget that in order to support a liquid and efficient bond market it will aim to maintain the stock of outstanding CGS at around 12 to 14 per cent of GDP, a level which the Reserve Bank views as appropriate for this purpose.”

Dedalus,

The Blyth speech was very entertaining and must’ve caused a few orthodox eyes to pop but was spoiled by the many references to revenue being the problem, despite his obvious grasp of what it means to have a fiat monetary system.

How is it possible to get all the neo-liberal myths lined up and then fail to join the dots?

I am yet to be convinced that those government clowns who imagine they are running the circus really know what they are doing. Irrespective of whichever party happens to be in office. Their immense egos and their narcissism (as manifested by their irritating displays of hubris, arrogance and pride) always get in the way of obtaining a real understanding of how things work. As H.G. Wells said in reference to human history, ignorance is the first penalty of pride.

I am most interested in the answer to Rod’s question. I would really like to know if it is necessary, in law, to issue bonds to cover the fiscal deficit. If it is not, why do they do it?

There is another mysterious behaviour (if true) of the RBA that I just heard about. It doesn’t lend to our banks and they therefore borrow overseas at higher rates and therefore cannot pass on all the interest rate cuts – while still continuing to make obscene profits.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-09-22/pettifor-how-the-rba-outsources-its-role-to-foreign-bankers/2911672

Why is this even permitted?

I have been working through John Armour’s RBA link and a couple of things stand out to me:

1. “Despite the low level of foreign currency issuance in 2013, foreign investor demand for Australian RMBS has been quite high, reflecting the lack of supply of RMBS in foreign markets, the global search for yield, and confidence in the high quality of the underlying collateral of Australian RMBS. Publicly available data indicate that, on average, around 40 per cent of each deal in 2013 was placed with foreign investors, and foreign investor participation at issuance has increased significantly.”

This seems to suggest with the bond market in Residential Backed Mortgage Securities we shouldn’t expect negative gearing to come off any time soon.

2. “The gradual improvement in RMBS market conditions since mid 2012, particularly the increase in private investor demand, led to the AOFM ceasing its RMBS purchases in 2012 and the government announcing the formal end of the AOFM’s RMBS investment program in April 2013.”

Does this mean the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) has been propping up the RMBS bond market?

Bill or others,

Does any agency publish daily statistics of the mentioned OPA similar to the US Daily Treasury Statement?