I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Tracing the origins of the fetish against deficits in Australia

Next week (Wednesday), I am giving the annual Clyde Cameron Memorial Lecture in Newcastle. Details are below if you are interested. Clyde Cameron – was a former Labor government Minister of Labour and other ministries (1972-75), a dedicated trade unionist, a defender of workers’ rights, and was aligned with the old-fashioned left-wing of the Party. He fell out with the Prime Minister at the time (Whitlam) over economic policy, in particular wages policy. The period of his demise is particularly interesting from an economic policy perspective and marked the beginning of the neo-liberal period in Australia and the rise of Monetarism as a macroeconomic policy framework. The type of propositions that were entertained by the Australian Treasurer, which were presented as TINA concepts in the public debate were flowering in policy making circles throughout the world. To some extent the current austerity mindset is the ultimate and refined expression of the trends that began around this time. The fetish against deficits first appeared in detail in the 1975-75 Commonwealth ‘Budget’ Papers. Cameron’s political demise in 1975 was intrinsically linked to his resistance against that fetishism, although his own solutions were similarly based on macroeconomic myths about the capacities of a currency-issuing government.

I don’t intend to cover all the historical events of the time in this blog. That would be a book-type exercise. Suffice to say that the – Federal Labor government – elected in December 1972 was the first non-conservative government for 23 years.

It last 3 years only and within that period had to go back to the electorate after being obstructed by a hostile upper house (Senate).

The Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam was a ‘new’ style of Labour leader – a lawyer rather than a working class person from a union background. The Party was becoming gentrified during this period and the simmering tensions between the old, left-wing union types and the Labor careerists (with tertiary education) was evident.

I don’t want to talk about his Government much – they did good (for example, end the Vietnam involvement, elevate the status of women, abolish the death penalty, no-fault divorce, aboriginal land reform, introduce a regional development strategy, etc) and they did unbelievable evil (for example, allowing Indonesia to take over Timor and slaughter the resistance)

They were also caught up in the various events in 1973, which severely disrupted the world economy and the currency markets.

The outbreak of hostilities in the Middle East in October 1973 (the 1973 Arab-Israeli War) was accompanied by the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC).

A few days later, on October 16, the Arab nations increased the price of oil by 17 per cent and indicated they would cut production by 25 per cent as part of a leveraged retaliation against the US President’s decision to provide arms to Israel.

The price of oil rose by around 3 times within eight months (US Energy Information Administration, 2013).

Australia was still oil-dependent and the OAPEC price hikes caused inflation to spike upwards.

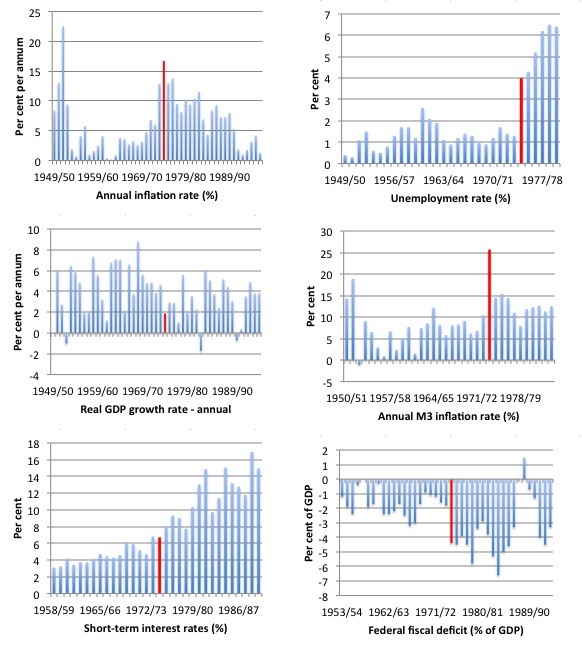

Here are 6 graphs which show what was happening (a bit) at the time to the main aggregates that were discussed in the fiscal process. The data comes from the RBAs – Australian Economic Statistics 1949-1950 to 1996-1997, Occassional Paper No 8.

The red column is 1974-75, which led into the formal ‘Budget’ deliberations (in those days, the Treasurer introduced the new fiscal year in mid-July – now it is early May).

The OPEC crisis has clearly driven a rise in inflation. At the same time, the rate of growth was falling and this started to drive the uneployment rate up. But worse was to come.

This break in the unemployment rate was the first time in the Post War period that the rate had risen above around 2 per cent. It has never come back to those levels as the neo-liberal policy dominance became entrenched. Now we celebrate 5 per cent unemployment rates to our shame!

There was strong nominal wages growth and profits push in this period in response to the rise in imported oil and its impact on the general price level.

The central bank started to push up interest rates but also the broad money supply grew sharply in that year.

The impact of the slowing economy and a progressive fiscal strategy started to push the fiscal deficit up. It would rise further as the economy remained sluggish and tax revenue growth dragged with the rise in unemployment.

It was a case of trying to cut fiscal deficits with spending cuts at a time the economy was slowing, which only made the fiscal deficit bigger as a proportion of GDP.

The inflation of the 1970s was what we now refer to as a supply-shock (cost-push) inflation. When the OPEC cartel flexed its muscles, it knew that the oil-dependent economies had little choice, at least in the short-run, but to pay up.

The oil price rise represented a real cost shock to all the economies – that is, a new claim on real output. The reality is that some group or groups (workers, capital) had to take a real cut in living standards in the short-run to accommodate this new external claim on real output.

At that time, neither labour or capital chose to concede and there were limited institutional mechanisms available to distribute the real losses fairly between all distributional claimants.

The resulting wage-price spiral came directly out of the distributional conflict that occurred. Another way of saying this is that there were too many nominal claims (specified in monetary terms) on the existing real output.

This is sometimes called the ‘battle of the mark-ups’; the ‘conflict theory of inflation’ or the ‘incompatible claims’ theory of inflation.

Sometimes this is referred to as ‘cost push’ inflation because its initial source is a push upwards in costs that are then transmitted via mark-ups into price level acceleration especially if workers resist the real wage cuts that capital tries to impose on them – to force the real costs of the resource price rise onto labour.

When firms receive higher nominal wage demands from workers, they need more working capital to facilitate the payments. They get that capital by expanding overdrafts and other short-term credit instruments.

Many firms did not want to lose market share as the result of a lengthy industrial relations dispute with their workforces. It became easier to agree to the wage demands and then retrieve their margins by pushing up prices. That is the way a wage-price spiral becomes entrenched.

Banks are happy to go along with it because they profit from the higher demand for credit. Ultimately, the central bank can decide to try to choke off the rising money supply with the limited capacity it has to accomplish that task – increasing penalty rates for demand for reserves (principally) although in that time, they used reserve ratios and other liquidity constraints.

But banks were also innovating and pushing businesses (such as finance companies) off their balance sheets into subsidiary companies that were not caught up in the central bank regulatory framework.

The result at the time was the strong growth in the money supply. The Monetarists, who by now were infesting the economics departments around the world, claimed that the inflation validated their claim that there was excessive monetary growth.

The debate turned on what was the ultimate cause. Was it the incompatible nominal demands for real output or was it the accommodative central bank policy stance?

Clearly, if the central bank runs a very loose monetary regime (low interest rates) at a time where demand for private credit is very high and the deposits created are being spent into an economy that cannot absorb that nominal spending in terms of providing extra real output, then inflation will result.

But the situation was more complicated than that. Real GDP was slowing and there was growing excess capacity.

On the fiscal front, the government can also choose to ratify this type of inflation by not reducing the nominal spending pressure or it can break into the wage-price spiral by raising taxes and/or cutting its own spending to force a product and labour market discipline onto the ‘margin setters’.

The weaker demand that results from this fiscal shift, ultimately, forces firms to abandon their margin push and the weakening labour markets cause workers to re-assess their real wage resistance. That is ultimately what happened in the 1970s.

Now that was background.

It is interesting to read the Cabinet documents from the period which are released by the National Archives after a time elapse of 30 years.

We focus on – 1975 – Whitlam and Fraser governments.

The conservative Fraser government took over in late 1975 after the Governor General (the Queen of England’s representative and head of state) sacked the Whitlam Labor Government.

It was a tawdry affair and violated the basic principles of democracy where an elected government is allowed to rule.

The CIA was also involved in this affair as a result of the Whitlam Government’s concern over the secret Pine Gap spy station. But that is another matter. The film – Falcon and the Snowman – has a passing reference to the CIA involvement.

Anyway, the 1975 Cabinet Records contain briefing documents which provide the historical record for the break with the Keynesian economic policy dominance and the beginning of what we now call neo-liberalism in Australia. A similar policy shift was occurring the world over and it is instructive to consider the reasoning – it resonates strongly with the nonsense we have to put up with still, some 40 years later.

Incidently, Clyde Cameron was Minister for Labor and Immigration up to June 6, 1975. He then was demoted to Minister for Science and Consumer Affairs as part of a neo-liberal putsch within the Government as Whitlam turned more conservative and started to be spooked by the outright opposition that the business lobby and sector had to his government.

The more substantive Ministerial change at the same time was the sacking of Jim Cairns as Treasurer on June 6, 1975 (he became Minister for Environment until he quit in dismay on July 2, 1975).

He was replaced by one William (Bill) Hayden as Treasurer on June 6, 1975 (he had previously been Minister for Social Security.

This Ministerial shift marked the beginning of neo-liberalism in Australian economic policy circles.

Among the selected documents that are available electronically for immediate download you can read the – 1975-76 Budget strategy (8.9 mb), which became the basis of the fiscal statement a few weeks later.

It contains a classic submission to Cabinet from the then Treasurer (dated July 15, 1975) – so not long after he became Treasurer. It was classic Treasury Groupthink. The Treasury had been baying at the moon to introduce more Monetarist orientated policies and they were able to take advantage of Hayden as an ‘illiterate’ in economic matters to push their agenda.

Before he was replaced as Treasurer, Jim Cairns had made a submission to Cabinet acknowledging that inflation had to be addressed but resisted the idea that the Government should introduce highly restrictive fiscal and monetary policy because he correctly reasoned that would create high unemployment.

And, after all, this was a Labor government and the Labor Party was the political arm of the trade unions and the defenders of social justice and promoters of social inclusion.

He argued that there should be some government spending restraint but this would be accompanied by a major political campaign to break into the wage-price spiral that was driving the inflation. He wanted trade unions to moderate their wage claims and take the real hit that the oil price rises required.

He also railed against the idea that wage increases automatically caused inflation. He said “some wage increases will not cause inflation”. In general, he promoted real wage increases in line with productivity growth and understood that these should not be inflationary. If prices still rose, it was all due to profit push.

In a Submission to Cabinet (Submission 1698, ‘Budget 1975-76: Options and Priorities’ [A5915, 1698]), starting on page 28 of the document linked (which is a collation of documents), Cairns made his point explicit.

He said on May 8, 1975 as part of the preparation for the upcoming fiscal statement:

If an attempt is made by monetary and/or fiscal and expenditure measures to reduce inflation very much and suddenly unemployment would increase significantly, investment and production would be depressed still further and the political prospects of the Government would be even more bleak than if an appropriate policy for the control of inflation is not adopted … We must not retreat from this campaign because of the political and media attacks which will be made upon it …

Further, he made a plea to his colleagues to stay true to their reformist, progressive policy vision:

We must not consent to surrender any significant part of our major social programmes and cultural advances as the result of pressure from the media and other anti-Labor forces. it is far better to be defeated while attempting to implement Labour policies than to be defeated after surrendering them. I do not believe we can win by surrendering these or if by any chance we did win that winning would be worthwhile. We must, I believe, keep the deficit as low as possible, carefully negotiate the money supply and strive for a reasonable wage and salary policy, but I believe even more, that we cannot tolerate unemployment or surrender our basic policies.

How many Treasurers would speak like that now? Perhaps Syriza (unless they become surrender monkeys are of this ilk in current times).

Of course, the surrender monkeys (business lackeys) were everywhere and Treasury was full of so-called ‘economic rationalists’ (now called neo-liberals) who had graduated from universities that had become besotted with the Chicago school nonsense.

The economy was starting to recover at the time Cairns made that submission and unemployment was not yet a significant issue.

But the fiscal deficit had risen (as a result of the slowdown) and the conservative press and business lobbies were out in force – as they are in the present time – baying at the moon about the size of the deficit.

Just as now, they totally misunderstood why it was rising and why it was good to rise – to buffer the slowdown in spending and to prevent unemployment from rising. Jim Cairns for all his faults understood that perfectly.

But the PM Whitlam was shifting to the right – he was never very far left anyway.

Cairns was duly sacked as Treasurer less than a month after presenting his fiscal plan to the Cabinet.

William George Hayden, who was of a conservative ilk became Treasurer and Chief Surrender Monkey. Clyde Cameron was replaced as Minister for Labor by James McClelland who was a notorious ‘union-basher’ (Source).

The documents show that Hayden was obsessed with reducing the fiscal deficit. He wanted major cuts to progressive areas of government spending – education, income support, public health, public housing and indigenous support. He also wanted concessions to big business.

In his Submission to Cabinet upon taking over as Treasurer (Submission 1928, ‘1975-76 Budget Strategy: Overall Policy Options’ [A5915, 1928] starting Page 53 of the document linked above), Hayden outlined the neo-liberal vision that still resonates today.

He claimed that if the deficit rose further it would be “quite outside the range of our own previous experience” – invoking fear of the unknown.

He claimed there would be:

… a pervasive psychological shock … with the most serious long-term consequences for the economy. Business investment would be depressed and employers would step up their search for survival by moving even deeper into their shells. Before long, the economic recovery would falter and reverse itself.

Sound familiar.

It became worse. He went on:

Investment would become even more depressed … another lift in the share of activity accounted for by government would further depress business and community confidence ….

He then started to make fundamental economic mistakes in his reasoning after his ideological introduction.

He said:

A deficit of the order presently in contemplation would also result in a flood of monetary liquidity. Initially this flood might merely pile up in idle balances; but even with little secondary credit expansion through the banking should there would probably be growth in the volume of money of 30 per cent or more during 1976.

Note the conflation. Even without the deficits, the banks could still generate credit expansion without the build up of idle balances.

Further, the deficit spending would only fuel inflation if there was no idle capacity and by the time he was writing there was room for more real growth (which was actually happening).

Then he made his classic comment:

We are no longer operating in the simple Keynesian world to which we had become accustomed – that world in which some reduction in unemployment could always be purchased if we were prepared to pay the price of some more inflation.

He rejected any tax increases to reduce the deficit because he claimed they would have:

… grave implications for profitability and investment.

The conclusion:

That leaves the burden of cut-back to the outlays side of the Budget. There is no doubt that a sharp cut-back is necessary …

He concluded that an inflation-first strategy was the Government’s “most important task” and if they do not pursue that “unemployment will persist and ultimately worsen”

He was thus buying into the Milton Friedman ‘short sharp shock’ syndrome where unemployment would fall to its natural level after a sudden cut in government deficit.

He then proposed cutting the deficit in half – a massive contractionary fiscal shift.

As part of his reasoning he made this statement about bond sales:

The viewpoint is sometimes advanced that expenditures do not need to be cut back nor the deficit reduced because a larger deficit can be financed in a non-inflationary way by borrowing from the non-bank public … Tax receipts differ from loan raising in their economic implications. The former represent compulsory withdrawals from private incomes while the latter involve voluntary decision by private savers regarding the forms in which they hold their assets. Private spending is likely to be affected much more by increases in tax than by increases in holdings of government securities …

These points aside, however, it is true that, within reason, the expansionary effects on the money supply of a larger deficit may be offset to the extent that the deficit can be financed by increased sale of government securities to the non-bank public …

Thus falling into the classic error that comes straight out the macroeconomics textbooks.

In this situation, like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Conclusion

It is interesting to go back into history to trace where shifts in policy occurred.

In Australia, it was the 1975-76 Fiscal Statement brought down in July 1975 that marked the beginning of the deficit fetish.

It got worse after that.

Information about the Clyde Cameron Memorial Lecture

The title of my talk will be – The Myths about Government Spending and Taxation and the lecture will occur on Wednesday, February 18 2015 from 18:00. It will finish about 20:00.

The venue is the University of Newcastle (City Campus) Room UNH421, corner of King and Auckland Streets, Newcastle.

Mr Richard Giles will also present for the Association for Good Government.

Attendance for this event is FREE, however for catering purposes please call (02) 6254 1897 or email: goodgov@bigpond.net.au to register your interest in attending.

Who was Clyde Cameron?

The Hon. Clyde R. Cameron A.O. (1913-2008) started his working life as a rouseabout and shearer and rose to become arguably Australia’s greatest ever Minister for Labour as part of the Whitlam Labor Government from 1972-1975. Mr. Cameron was a great Australian statesman who truly understood political economy and who devoted his life to securing just rewards for Australian workers.

In my talk, without demeaning Clyde Cameron, I will suggest he didn’t quite understand political economy being caught up in the narrative of the times. But he certainly opposed the deficit fetishism that Bill Hayden introduced into the public debate, which marked the beginning of the neo-liberal period in Australia and the rise of Monetarism as a macroeconomic policy framework.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I reckon that would be one of my favourite posts, Bill. Understanding what happened in the 1970s goes a long way in helping to figure out the way the world works.

Cheers.

Wages add to prices/ inflation.

There was a spectacular increase in oil inputs during the 50s and 60s as both men and women chased purchasing power while using their cars as the primary instruments of this endeavour

Certainly people in Ireland and Spain changed from a semi peasant like method of work practise (although working within the framework of a wider capitalistic system) into proper wage slaves.

Looking back now we can come to understand that the large wage rises of the 60s and 70s were designed to entrap people within the system.

The labour stooges were no longer needrd by the late 70s and could therefore be safely disposed of.

Bill,

The budget records are available from the government website. Why does your graph show the period between 1970 to 1975 as being in deficit.

The treasury records show that these years were in surplus: http://www.budget.gov.au/2012-13/content/myefo/html/13_appendix_d.htm

Am I missing something.

Dear Bill

When inflation results from capital and labor together wanting more than 100% of GDP, the best policy is for the government to step in and try to have a policy of wage and price control or else persuade labor and capital to moderate their claims. It certainly is a more humane approach than the policy of causing high unemployment through a very restrictive monetary policy. According to Paul Krugman, Israel managed to bring inflation under control by getting labor and capital together and persuading them to moderate their claims.

Thanks to all who replied to my question yesterday.

Regards. James

@James

Why this artifical distinction between labour and capital?

Me thinks we need redistribution

I favour social credit but there are other more capitalist methods such as binary economics.

Given resistance from the usual Jewish suspects such as Friedman and Samuelson it was perhaps a dangerously effective policy.

Bill,

When writing anything on the deficit and debt, please also do a version using monosyllabic words and sentences of no more than three words so that Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart can understand it..:-)

Could Bill give his thoughts. On the ongoing Comer vs Bank of Canada legal action?

I wonder if a public banking system could of provided firms with lower capital costs or even zero interest credit.This would lower financing costs for firms.Forcing the losses incurred by the real oil cost increase off labour and profits and onto private finance(by undercutting it with public banking).This may have reduced the cost push inflation and mark up/margin spirals to some extent,by lowering the cost of doing business.

I see Mr Krugman was musing about money today with a passing reference to heterodox economists.

Thanks Paul.

Thanks for this article. I was in my 20s at the time, involved in making a living, and awareness of the bigger picture was lacking. It is useful to see the times in perspective.

Obviously, the Australian Labor Party has learnt next to nothing from those events. Obviously,nobody would expect the Tories to learn anything about anything. The current LNP leadership antics are an example.

Thank you for this discussion.

Modern monetary theory looks very plausible indeed, but one thing that causes me some difficulty is lack of clarity about whether the analysis at certain points is structural (as in analysis of the economic system as such) or historical (looking at things happening over time). I’d like to know if there is any good discussion of this distinction.

Chris

I think you might be confusing Bill’s opinions that follow his understanding of MMT with MMT itself which is about as strutural as anything you can get in the economics of a monetary economy in that it describes the actual workings of the monetary system including the operational realities of banking and fiat currencies as they currently are. In other words it provides a coherent framework consistent with double -entry accounting that no other ‘theory’ comes close to. In mainstream economics those realities and that framework are simply missing or ignored.

Richard Koo has backed up your statement about expanding reserves does not create inflation or credit. Have a look at his latest book and blog where the world has huge reserves and no inflation and no credit expansion as they are trying to clean up their balance sheets. I think its called a balance sheet recession. Will your CC lecture be on a blog on 18th or later?

And Bill when are you going to do do a MOOC on MMT as we all need it. I realize you are very busy but Prof Perry Mehrling did Money and Banking through INET in 2013 at Columbia Uni and it was brilliant. He had 32000 students. that is the way to move MMT forward.

You should include an invitation to participate in the MOOC to: Jovial Joe and his sidekick Josh F as well as Neo-classical Chris B. Why not embarrass them into getting involved and maybe they they might abandon their collective folly that is leading us down the path to who knows where.