Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – March 14, 2015 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Start from a situation where the external surplus is the equivalent of 2 per cent of GDP and the fiscal surplus is 2 per cent of GDP. If the fiscal balance remains unchanged and the external surplus rises to 4 per cent of GDP then:

(a) National income rises and the private surplus moves from 4 per cent of GDP to 6 per cent of GDP.

(b) National income remains unchanged and the private surplus moves from 4 per cent of GDP to 6 per cent of GDP.

(c) National income falls and the private surplus moves from 4 per cent of GDP to 6 per cent of GDP.

(d) National income rises and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP.

(e) National income remains unchanged and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP

(f) National income falls and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP.

The answer is Option (d) National income rises and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP.

First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses:

(2) Y = C + S + T

where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined).

You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write:

(3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get:

(4) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness.

So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government fiscal balance and external:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G – T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process.

Second, you then have to appreciate the relative sizes of these balances to answer the question correctly.

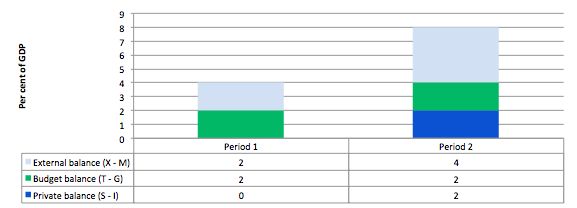

Consider the following graph and accompanying table which depicts two periods outlined in the question.

In Period 1, with an external surplus of 2 per cent of GDP and a fiscal surplus of 2 per cent of GDP the private domestic balance is zero. The demand injection from the external sector is exactly offset by the demand drain (the fiscal drag) coming from the fiscal balance and so the private sector can neither net save or spend more than they earn.

In Period 2, with the external sector adding more to demand now – surplus equal to 4 per cent of GDP and the fiscal balance unchanged (this is stylised – in the real world the fiscal balance will certainly change), there is a stimulus to spending and national income would rise.

The rising national income also provides the capacity for the private sector to save overall and so they can now save 2 per cent of GDP.

The fiscal drag is overwhelmed by the rising net exports.

This is a highly stylised example and you could tell a myriad of stories that would be different in description but none that could alter the basic point.

If the drain on spending (from the public sector) is more than offset by an external demand injection, then GDP rises and the private sector overall saving increases.

If the drain on spending from the fiscal balance outweighs the external injections into the spending stream then GDP falls (or growth is reduced) and the overall private balance would fall into deficit.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

A rising fiscal deficit necessarily indicates that fiscal policy is expansionary.

The answer is True.

The actual fiscal deficit outcome that is reported in the press and by Treasury departments is not a pure measure of the discretionary fiscal policy stance adopted by the government at any point in time.

Economists conceptualise the actual fiscal outcome as being the sum of two components: (a) a discretionary component – that is, the actual fiscal stance intended by the government; and (b) a cyclical component reflecting the sensitivity of certain fiscal items (tax revenue based on activity and welfare payments to name the most sensitive) to changes in the level of activity.

The former component is now called the “structural deficit” and the latter component is sometimes referred to as the automatic stabilisers.

The structural deficit thus conceptually reflects the chosen (discretionary) fiscal stance of the government independent of cyclical factors.

The cyclical factors refer to the automatic stabilisers which operate in a counter-cyclical fashion. When economic growth is strong, tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this decreases during growth.

In times of economic decline, the automatic stabilisers work in the opposite direction and push the fiscal balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit. These automatic movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

The problem is then how to determine whether the chosen discretionary fiscal stance is adding to demand (expansionary) or reducing demand (contractionary). It is a problem because a government could be run a contractionary policy by choice but the automatic stabilisers are so strong that the fiscal balance goes into deficit which might lead people to think the “government” is expanding the economy.

So just because the fiscal balance goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this ambiguity, economists decided to measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the fiscal balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

As a result, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construction of the fiscal balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the fiscal position (and the underlying fiscal parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

This framework allowed economists to decompose the actual fiscal balance into (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical fiscal balances with these unseen fiscal components being adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal balance is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal balance into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The question then relates to how the “potential” or benchmark level of output is to be measured. The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry among the profession raising lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s.

As the neo-liberal resurgence gained traction in the 1970s and beyond and governments abandoned their commitment to full employment , the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

The estimated NAIRU (it is not observed) became the standard measure of full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then mainstream economists concluded that the economy is at full capacity. Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

Typically, the NAIRU estimates are much higher than any acceptable level of full employment and therefore full capacity. The change of the the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance was to avoid the connotations of the past where full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels.

Now you will only read about structural balances which are benchmarked using the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending because typically the estimated NAIRU always exceeds a reasonable (non-neo-liberal) definition of full employment.

So the estimates of structural deficits provided by all the international agencies and treasuries etc all conclude that the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is – that is, bias the representation of fiscal expansion upwards.

As a result, they systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

The only qualification is if the NAIRU measurement actually represented full employment. Then this source of bias would disappear.

But in terms of the question, a rising fiscal deficit can accompany a contractionary fiscal position if the cuts in the discretionary net spending leads to a decline in economic growth and the automatic stabilisers then drive the cyclical component higher and more than offset the discretionary component.

But it still remains that a rising fiscal deficit is pumping net financial assets (net spending) into the non-government sector, which is an expansionary act. It would be better if the expansion came via discretionary actions but automatic stabilisers when working against the cycle are also expansionary.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Saturday Quiz – April 24, 2010 – answers and discussion

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 3:

If private households and firms decide to lift their saving ratio the national government has to increase its net spending (deficit) to fill the spending gap or else economic activity will slow down.

The answer is False.

Please refer to the conceptual explanations in Question 1.

To help us answer the specific question posed, we can identify three states all involving public and external deficits:

- Case A: Fiscal Deficit (G – T) < Current Account balance (X - M) deficit.

- Case B: Fiscal Deficit (G – T) = Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case C: Fiscal Deficit (G – T) > Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

When the private domestic sector (that is, households and firms) decide to lift their overall saving ratio, we normally think of this in terms of households reducing consumption spending or firms reducing investment.

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms layoff workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession. Interestingly, the attempts by households overall to increase their saving ratio may be thwarted because income losses cause loss of saving in aggregate – the is the Paradox of Thrift. While one household can easily increase its saving ratio through discipline, if all households try to do that then they will fail. This is an important statement about why macroeconomics is a separate field of study.

Typically, the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur – in the form of an expanding public deficit or an offsetting increase in net exports.

The fiscal position of the government would be heading towards, into or into a larger deficit depending on the starting position as a result of the automatic stabilisers anyway.

If there are not other changes in the economy, the answer would be true. However, there is also an external sector. It is possible that at the same time that the households are reducing their consumption as an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public fiscal balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving ratio if net exports were strong enough.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Saturday Quiz – May 22, 2010 – answers and discussion

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

A rising fiscal deficit necessarily indicates that fiscal policy is expansionary.

The answer is True.

Not true!

It could be due to automatic stabilisers.

Dear Bob (2015/03/15 at 20:46)

That was the point of the question. The operation of automatic stabilisers in a downturn is expansionary – they expand the deficit (net public spending).

The answer is TRUE!

best wishes

bill

Ah, OK. Doh.

I managed to get that one wrong too.

I reasoned that external deficit could be rising faster than the govt’s budget deficit – in which case fiscal policy could still be contractionary – because it wasn’t rising fast enough!