The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Greek bank deposit migration – another neo-liberal smokescreen

There was a news report on Al Jazeera on Friday (January 5, 2015) – Greece’s left-wing government meets eurozone reality – which contained a classic quote about the supposed incompetence of the new Greek Finance Minister. A UK commentator, one Graham Bishop was quoted as saying “If you’re a professor of macroeconomics and a renowned blogger, you probably don’t understand precisely how the banking systems works”. Take a few minutes out to recover from the laughing fit you might have immediately succumbed to on reading that assessment. As if Bishop knows ‘precisely’ how the system works! The context is the current news frenzy about the deposit migration out of Greek banks as a supposed vote of no confidence in the anti-austerity stand taken by Syriza. Having voted overwhelmingly for Syriza, Greeks are now allegedly voting against the platform by shifting their deposits out of the Greek banking system. A close look at things suggests that is not going on and it wouldn’t matter much if it was.

Bishop makes money by promoting the European Union and the common currency. He advertises himself as the 33rd “Top 40 British EU policy ‘influencers'”.

He previously worked in the financial markets. He was the UK representative on the European League for Economic Cooperation (ELEC) and at a meeting in Brussels on March 21, 1997 was on the record as supporting the proposition that (Source):

… the UK will not join EMU from the beginning, but will join probably later, after 4 or 5 years, for instance in 2002.

That was plain wrong.

He also contributed to a 1997 Report published by the Centre for European Reform (CER) – Britain and EMU: The case for joining – where he claimed that the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) would “ensure that states cannot become liable for each others’ debts”.

He also thought that if Britain joined the Eurozone, the financial sector in London “should be able to capture a substantial share of the euro market” which would be “a prize indeed for Britain joining EMU”.

Interestingly, Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf also had a chapter in that Report where he concluded that “early entry into European economic and monetary union would be best for Britain”. He also noted that “both the benefits and costs of EMU are commonly exaggerated”. I guess he doesn’t agree with that now.

In a 2006 Report – The Governance of the Eurozone – which was produced by a team including Bishop, the Foreword stated:

It is hard to remember that EMU was the driving force of the European project less than a decade ago. Maybe we take the success of EMU for granted. Maybe we underestimate the success of EMU in preventing one generation from placing the burdens of debt and inflation on its successors.

That was a good call! Not!

In 2008, before the crisis revealed itself, Bishop contributed to a volume – 10 Years of the Euro: New Perspectives for Britain – published by a group who wanted “to help place the case for Britain joining the Euro back upon the political agenda and to provide the beginnings of an ongoing forum for its promotion”.

Bishop praised the Eurozone’s decision to strengthen the SGP after the 2004 crisis involving Germany and France and its fiscal austerity.

He said that “The sustainability, let alone credibility, of British fiscal policy is now being seriously questioned – with good reason”. So he was part of the bandwagon that lead to austerity being unecessarily imposed on Britain which worsened the recession.

He wrote:

Budget deficits have to be financed – either from domestic savings or from foreign inflows (assuming that the Bank of England’s banknote printing works at Debden will not be compelled to work overtime!) … the UK seems close to a vicious spiral in its public finances … Given the insufficiency of domestic savings and the imminent risk of a spiralling crowding out of private sector credit demands, the role of foreign inflows is vital.

So you see that the ’33rd top influencer’ was part of the throng predicting disaster for the UK government – none of which actually ever occurred, nor ever would have given that the UK is the currency issuer.

To solve the alleged ‘crisis’ Bishop said that:

Under these circumstances, the creation of an anchor for sterling may require the certainty that this will never happen again. That would point to the abolition of sterling and its replacement by a currency that has already established a solid track record – the Euro.

So top call! (-: (smile inserted for Americans who might think I was serious – and that was a joke too!).

Bishop should go on the speaking circuit with a cast including Jean-Claude Trichet who consistently praised the success of the Eurozone as unemployment was rising and growth rates were falling. After nearly 8 years of crisis, the level of GDP is still struggling to reach 2007 levels.

If the UK was a member of the EMU, it would be locked into a prolonged crisis like all the Eurozone nations, including a poorly performing Germany. As it is, the Conservative government tried its hardest to replicate the sort of madness that was going on in the Eurozone.

I think I would rather be a “a professor of macroeconomics” who apparently doesn’t “understand precisely how the banking systems works” than be the ’33rd top influencer’ who thinks the Eurozone has been such a success that currency-issuing governments like the UK should seek to be part of!

In April 2011, he wrote an Op Ed piece for the – European Payments Council – newsletter – More Europe is Needed, Not Less

The EPC is a private organisation comprising banks and peak banking associations which lobbies policy makers on behalf of the commercial banks in relation to developments to the payments system.

The newsletter introduced the Op Ed by claiming that the:

… recent pressures on the single currency resulting from the fiscal situation in several EU Member States.

You can see their bias.

I would say that the “fiscal situation in several EU Member States resulted from the decision to adopt a single currency” and then refuse to create a single federal fiscal authority and, in its place, impose absurd fiscal rules on the fiscal operations of the Member States.

In other words, the reverse causality.

Bishop’s argument is that to solve the crisis (remember he was writing in 2011), European integration had to be extended. He praised the endeavour of EU politicians in launching the “Europe 2020 Strategy … [which] … sets out a vision to achieve high levels of employment, a low carbon economy, productivity and social cohesion”. His foresight was lacking.

By 2015, there is virtually no hope that the targets set out in that strategy will be realised. It has been sabotaged from within – by the flawed policy framework introduced to deal with the crisis.

But, relevant to today’s topic, Bishop also praised the – SEPA (the Single Euro Payments Area – and claimed its impact “far exceeds payments, cash management and related services”.

The SEPA started in February 2014 (for Eurozone nations) and replaced the national-level payments methods with an integrated and standardised payments system for the EU as a whole, which makes it easy to transfer euros from one bank to another. The aim was to create a EU-level payments system and eliminate the national clearing markets.

SEPA means, for example, that a firm no longer needed multiple bank accounts across the national spaces in which it sold or procured. It meant that all payments (in or out) were standardised and transaction costs were thus reduced.

Bishop claims that the SEPA:

… establishes an effective ‘referendum veto’ to be exercised by citizens whose national governments might contemplate leaving the euro. In SEPA, citizens are empowered to embed the freedom and the choices associated with the single market so deeply in the economy to make it impossible for any EU government which adopted the euro to abandon the common currency …

With SEPA, any citizen who fears that his homestate is about to leave the euro to implement a major devaluation can protect themselves by transferring their liquid funds into a bank in another euro country – in an instant and at negligible cost. In effect, this is a free option for all citizens and amounts to an instantaneous referendum on government policy. Such an outflow of retail liquidity from a banking system would cause its rapid collapse.

The inference is that the institutional arrangements governing banking in the Eurozone would impose such costs on people that they become locked into the broader monetary union irrespective of how well it performs. That sounds like insanity to me but is consistent with the litany of decision-making mistakes that the European elites have made.

But is he right?

Well, I am just a professor of macroeconomics who doesn’t know how banking operates but here is a different picture.

Bishop’s allegations were directed at the new Greek Finance Minister, who I can assure you knows quite a bit about the way banking operates. But he can defend himself.

But the accusations are in the context of the flurry of news in the last few weeks about the allegedly ‘massive and crippling’ outflows of bank deposits from Greek banks as a sign that depositors are scared of Syriza’s decision to stand up to the unelected Troika.

Following Bishop’s claims, if there are such outflows then this must mean the Greek voters – that is, people who vote! – are delivering a vote of no confidence in Syriza already – even before the election.

Funny thing that despite that apparent vote of no confidence, Syriza were convincingly elected on an anti-austerity platform vowing to restore some degree of self-determination to Greek socio-economic outcomes. I have written before about why I think they will struggle while remaining within the Eurozone.

The following sequence of recent blogs traced my thinking on the issue:

- Greece – two alternative views

- Germany should be careful what it ‘allows’

- Greek elections – a solution doesn’t appear to be forthcoming

- Conceding to Greece opens the door for France and Italy

- Germany has a convenient but flawed collective memory

But it remains that Syriza is posturing to restore dignity and break the anti-democratic shackles that the Troika has on the nations.

Like all elite hegemonies, the Troika benefits from the mindless financial and economics commentary in the mainstream media. The story about deposit migration is, of course, one such beneficial narrative. It reinforces the claim that market forces will destroy the banking and financial systems of any nation that dares buck against the Troika orthodoxy of austerity and rectitude.

I use the term rectitude because it brings in the religious (ideological) dimension of the issue. The Groupthink is so overwhelming that the elites have everyone believing that it is somehow sinful for a government to run a deficit in defense of full employment. Guilt must be followed by penitence and in Troika-speak that means 25 per cent unemployment for 7 odd years (over 50 per cent youth unemployment) and rising poverty.

As an example of the deposit migration stories, Bloomberg Business ran an article on January 29, 2015 – Greek Bank Deposit Flight Said to Accelerate to Record – which said that:

Greek bank deposit outflows last week accelerated to record levels amid concern about lenders’ liquidity and the outcome of the nation’s negotiations with creditors, according to a person familiar with the matter.

No official source was of course cited. Only a “personal familiar with the matter”.

The monthly deposits data is only publicly available up to December 2014. So our ‘person familiar’ has unpublished sources or is making it up based on some selective estimates.

The reports are now claiming things are worse than in May 2012. In that month, Greek bank deposits fell by 5.1 per cent (on the previous month), which in the scheme of things is a fairly big flow for a single month.

In December 2014, Greek bank deposits fell by 2.4 per cent (on the previous month).

To put those percentage numbers in perspective though, the total private sector (households and firms) decline in deposits in May 2012 amounted to 8,514 million euros whereas the fall in December 2014 amounted to just over 4,011 million euros.

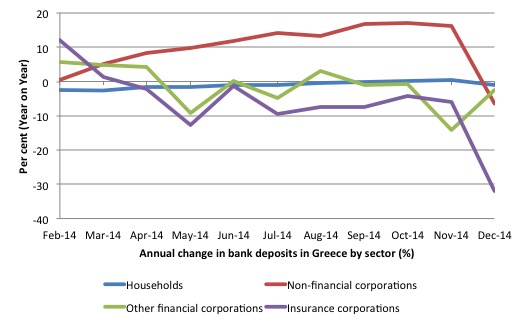

But the sectoral breakdowns are interesting, given Bishop’s claim about people voting with their feet.

The sectoral breakdown for May 2012, was household deposits – down 5 per cent, non-financial corporations – down 7.2 per cent, other financial corporations – down 1 per cent and insurance companies – up 2 per cent.

The most recent sectoral breakdown was household deposits – down 1.3 per cent, non-financial corporations – down 5.5 per cent, other financial corporations – down 5.9 per cent and insurance companies – down a staggering 27.8 per cent.

So households in Greece haven’t shifted much at all.

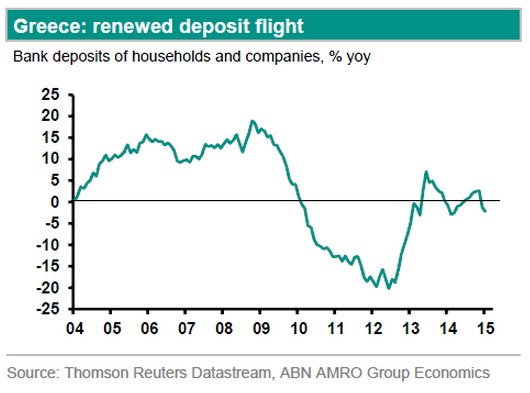

The UK Guardian’s live commentary on Friday – Greek debt crisis sharpens, as US jobs report smashes forecasts – live updates – opened with this graph that came from an investment bank.

Note the horizontal axis.

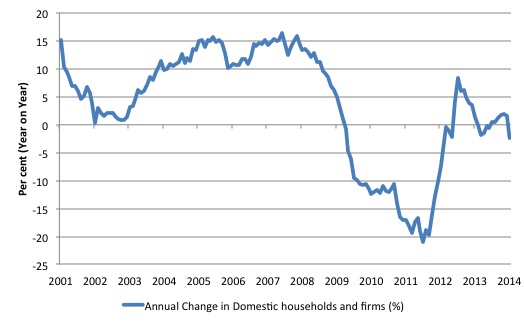

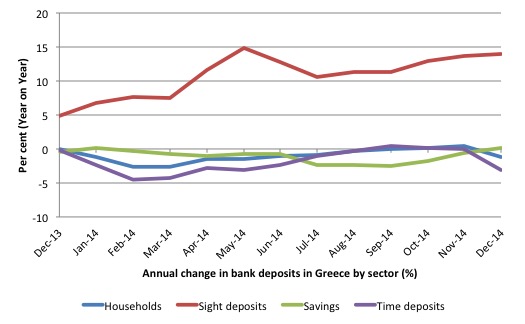

Here is the current publicly available data from the Bank of Greece – Deposits held with credit institutions, breakdown by sector – graphed up to the end of 2014.

I could have rigged the horizontal axis by adding 2015 to the column of data (with no observations) to give the impression that the fall in deposits was following the election of Syriza.

The other question is to understand which sectors are shifting deposits. The following graph shows that the shift in December 2014 mostly came from Insurance Companies. Households did not withdraw their deposits in any substantial fashion.

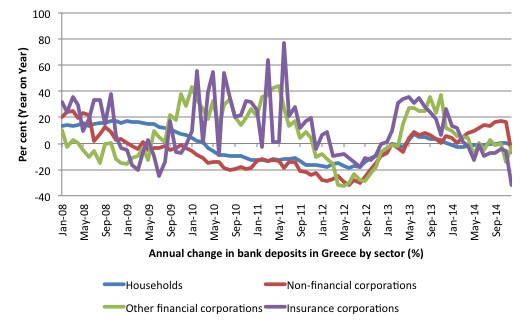

The next graph takes a longer look – from January 2008 to December 2014 – of the sectoral deposits. The major volatility in Greek banking deposits comes from the financial sector including insurance corporations, which mostly reflects speculative positioning.

The next graph decomposes the different types of deposits for households – into sight deposits (which are accounts that can be quickly transferred without penalty or converted into cash), saving accounts (less liquid) and time deposits (usually with some restriction on withdrawal inside the term of the certificate).

Sight deposits rose sharply in the latter part of 2014. Savings deposits also rose in December 2014 after falling for some months. Term deposits fell by 3 per cent in December 2014. A possible interpretation is that rather than migrate deposits out of the Greek banking system people are keeping high levels of liquidity.

But this could also be a sign of households being increasingly strained for liquidity by unemployment and other income constraints and thus needing to keep savings in a liquid form.

All of this detail aside, the fact remains that the Greek banks need to have reserves to maintain their operations and a major run on deposits would be problematic.

This is not the same thing as saying, as mainstream economic theory claims, that banks are institutions that take in deposits which then provides them with the funds to on-lend at a profit. According to this flawed view, the ability of private banks to lend is considered to be constrained by the reserves they hold.

While students find it hard to think outside of this construction, the reality is very different. Banks do not operate in this way. From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) private bank lending is unconstrained by the quantity of reserves the bank holds at any point in time. We say that loans create deposits.

Please read my blog – The role of bank deposits in Modern Monetary Theory – for more discussion on this point.

Further reading is available in these blogs:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Money multiplier – missing feared dead

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained

Banks certainly seek to maximise return to their shareholders as long as that doesn’t conflict with the management’s aims to maximise salaries and bonuses for themselves. There is clear evidence that the management prioritises the latter over the former and will let the bank go broke as long as they preserve their own entitlements.

In pursuing that charter, they seek to attract credit-worthy customers to which they can loan funds to and thereby make profit. What constitutes credit-worthiness varies over the business cycle and so lending standards become more lax at boom times as banks chase market share.

A few refresher points:

First, banks do not lend reserves! Banks reserves are liabilities of the central bank and function to ensure the payments (or settlements) system functions smoothly.

That system relates to the millions of transactions that occur daily between banks as cheques are tendered by citizens and firms and more. Without a coherent system of reserves, banks could easily find themselves unable to fund another bank’s demands relating to cheques drawn on customer accounts for example.

Depending on the institutional arrangements (which relate to timing), all central banks stand by to provide any reserves that are required by the system to ensure that all the payments settle.

Banks thus will have a reserve management area within their organisations to monitor on a daily basis their status and to seek ways to minimise the costs of maintaining the reserves that are necessary to ensure a smooth payments system.

Banks can trade reserves between themselves on a commercial basis but in doing so cannot increase or reduce the volume of reserves in the system. Only government-non-government transactions (which in MMT are termed vertical transactions) can change the net reserve position.

The important point for today though is that when a bank originates a loan to a firm or a household it is not lending reserves. Bank lending is not easier if there are more reserves just as it is not harder if there are less. Bank reserves do not fund money creation in the way that the mainstream economics textbooks depict it.

MMT notes that bank loans create deposits not the other way around. Reserve balances have nothing to do with this – they are part of the banking system that ensure financial stability.

Second, depending on the way the central bank accounts for commercial bank reserves, the banks will seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period. They can borrow from each other in the interbank market but if the system overall is short of reserves these ‘horizontal’ transactions will not add the required reserves. In these cases, the bank will sell bonds back to the central bank or borrow outright through the device called the ‘discount window’.

At the individual bank level, certainly the ‘price of reserves’ will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds. But the reserve position per se will not matter. So as long as the margin between the return on the loan and the rate they would have to borrow from the central bank through the discount window is sufficient, the bank will lend.

The major insight is that any balance sheet expansion which leaves a bank short of the required reserves may affect the return it can expect on the loan as a consequence of the “penalty” rate the central bank might exact through the discount window. But it will never impede the bank’s capacity to effect the loan in the first place.

So it is quite wrong to assume that the central bank can influence the capacity of banks to expand credit by adding more reserves into the system. Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit – for further discussion.

So what role do bank deposits play? How does this relate to the MMT claim that loans are just created from nowhere?

Think about what happens when you go to the bank and ask for credit. This is happening every hour of every business day as households and firms seek credit. The loan is a bank liability which can be used by the borrower to fund spending. When spending occurs (say a cheque is written for a new car), then the adjustment appears in the reserve account the the bank that the cheque is drawn on holds with the central bank.

Does the bank’s reserve fall as a consequence? Not necessarily because it depends on other transactions. What happens if the car dealer also banks with Bank A (the consumer’s bank)? Then Bank A just runs a contra accounting adjustment (debit the borrower’s loan account; credit the car dealer’s cash account) and the reserve balance doesn’t change even though a settlement has taken place.

There are more complicated situations where the reserve balance of Bank A is not implicated. These relate to private wholesale payments systems which come to the settlements system (aka the ‘clearing house’) at the end of the day and determine a ‘net position’ for each bank. If Bank A has more cheques overall written for it than against it then its net reserve position will be in surplus.

What does that all mean? Loans are not funded by reserves balances nor are deposits required to add to reserves before a bank can lend. This does not deny that banks still require funds in order to operate. They still need to ensure they have reserves. It just means that they do not need reserves before they lend.

Private banks still need to ‘fund’ their loan book. Banks have various sources of funds available to them including the discount window offered by the central bank which I explained above. The sources will vary in ‘cost’. Banks clearly try to get access to funds which are cheaper than the rate they charge for their loans. So they will go to the cheapest funding source first and then tap into more expensive funding sources are the need arises. They always know that they can borrow shortfalls from the central bank at the discount window if worse comes to worse.

So the profitability of the loan desk is influenced by what they can lend at relative to the costs of the funds they ultimately have to get to satisfy settlement. So the price that the bank has to pay for deposits (one source of such funds) impact on the profitability of its lending decisions.

So the migration of deposits in the Greek banking system, if it occurs in any substantial way, will alter the costs of generate necessary reserves and potentially create a liquidity crisis should there be a major run on the banks deposits.

But there is still the Bank of Greece, which is part of the Eurosystem.

As part of its monetary policy operations, the ECB provides – Emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) – which is described in this document – ELA Procedures.

The existing ELA facility allows the ECB to provide “central bank money” (that is, reserves) to any solvent financial institution “facing temporary liquidity problems, without such operation being part of the single monetary policy”.

The rules prohibit the ELA being used to provide “overdraft facilities for official bodies” – that is, for the ECB to directly purchase government bonds.

But patching up the Greek banks for a declining deposit base would be squarely in the ambit of the ELA.

The decision last week by the ECB to suspend the waiver on Greek government bonds being used as collateral for liquidity access at the ECB by Greek banks was stupidly aggressive but does not change the access that the Greek banks have through the Bank of Greece to the ELA.

I noted at the time that the ECB should never have been part of the Troika, which saw its role to discipline fiscal policy. That level of interference should be challenged in the European courts as it surely is outside of its legislative charter.

As of Wednesday (February 11, 2015), the demand for liquidity from the Greek banks will come through the Bank of Greece. That is a simple matter. The ECB under its standing facilities reviews ELA on a bi-weekly basis, which means it could decide to suspend the scheme altogether.

Should it do that the Greek banks would surely crash and a financial crisis would ensue. It would also mean that the ECB was breaching its own charter to ensure there was financial stability in the Eurozone. Deliberately forcing the Greek banks to crash and creating a financial crisis is not consistent with that charter.

Equally, the ECB has no legislative charter to make decisions based on fiscal issues. Whether Greece is running a deficit of 10 per cent of GDP or 1 per cent of GDP is not part of the decision-making environment that the ECB should consider unless it believes such actions will cause an acceleration of inflation.

Further, if the ECB did cut the Greek banks out of the ELA it would certainly force the Greek government to withdraw from the Eurozone and then the consequences for the German and French banks and the ESM (which holds a large proportion of Greek government debt at present) would be significant and negative.

For Greece, the Government could legislate to take the Bank of Greece out of the ECB system of national banks and instruct its board to fund its deficit in the new currency while it went about creating work for the unemployed and restored public infrastructure within the limits of the resources it had available.

It could get some of the newly employed workers to attend to the massive tourist boost that would follow should the new currency decline significantly.

As I noted the other day, I would not expect a significant exchange rate depreciation of the new drachma in the short-term given the fact that supply would be limited. The examples often used, such as Iceland and Argentina, all relate to currencies that were already supplied in volumes to the foreign exchange markets.

Conclusion

The Greek bank deposits stories are in my view not particularly significant. There are no runs on the banks as there were in the UK at the onset of the crisis.

Bank deposits have been shifting around a lot anyway.

But unless the ECB abandons its charter, the Bank of Greece will supply as much liquidity as is needed to maintain financial stability under the ECB’s own policy frameworks.

Should the ECB board go crazy and cut the Greek banks out of the ELA then they would be playing a very dangerous card for the rest of Europe. Greece would exit and restore its true sovereignty and end up winners by a long way.

But then, I am just a professor of macroeconomics who knows nothing of the operations of banking systems.

Alan Greenspan

I don’t often agree with what former US Federal Reserve Bank Chairman Alan Greenspan was quoted in a BBC news report (February 8, 2015) – Greece: Greenspan predicts exit from euro inevitable – as saying:

I don’t think it will be resolved without Greece leaving the eurozone … I believe … [Greece] … will eventually leave. I don’t think it helps them or the rest of the eurozone – it is just a matter of time before everyone recognises that parting is the best strategy … The problem is that there there is no way that I can conceive of the euro of continuing, unless and until all of the members of eurozone become politically integrated – actually even just fiscally integrated won’t do it.

The unwillingness (and impossibility) of the Member States to surrender their national identities and become ‘states’ within a federal Europe, with full fiscal responsibility being ceded to the federal level under the care of the a democratically elected federal government is the reason the Eurozone remains in crisis and cannot generate sustained economic prosperity.

Greenspan is correct on that point. We knew that in 1990 once the Delors Report (Plan) was unveiled. We knew it during the Maastricht deliberations in 1991. We have known it ever since then. The crisis proved what we knew was correct.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Should it do that the Greek banks would surely crash and a financial crisis would ensue.”

Depends how it is played surely. The banking system is merely a set of ‘currency’ pegs between the liabilities of different organisations. If the ECB ‘withdraws’ ELA then all it is saying is that it won’t extend the TARGET2 overdraft the Greek central bank has at the ECB and refuses to clear at par. Which then instantly means that Greek Euros start to float against ‘German’ Euros – since to clear payments elsewhere in the Eurozone you’d have to resort to good old correspondence banking.

Yes all the banks would go into administration and there’d be a heck of a legal mess, but the banks are heavily owned by the HFSF anyway so it shouldn’t be too difficult to pass the legislation necessary to get all the losses in German Euros onto the balance sheet of the HFSF and liquidate that to write them out.

I don’t think though that administration of the banks should stop the payment system in Greece from continuing to function if the bankruptcy protection system works effectively. A simple pre-pack and refloat in Greek Euros should get the Greece system back on its feet pretty quickly. They already print their own Euros (identifiable with the Y serial number) and coins with greek faces.

I think separation is workable. Difficult but workable. The Eurosystem is already heavily decentralised because the partners really don’t trust each other – despite the integrationist efforts of free market clowns like Bishop.

Dear Bill and others

When banks lend money to a borrower, they simply create a deposit, which then can be used by the borrower to make payments. In fact, the bank has created money. Fair enough. What I don’t quite understand is, how can a bank go broke if it can actually create money?

Suppose that Bank A has one customer, Peter. Peter receives a loan of 10 million. He uses his newly created deposit to make payments totaling 10 million. All those payments go to people who have accounts with banks other than Bank A. Bank A now has no more deposits, but why should that be a problem since no further payments can be made from accounts at bank A and Peter still owes 10 million to bank A?

Regards. James

Greenspan of regrets I have a few fame ………including Lincoln savings and loan.

The man is a particular type of criminal.

With the law on his side.

https://archive.org/details/AV_410-SAVINGS_and_LOANS-STOLEN_and_LOOTED

http://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/20/business/greenspan-s-lincoln-savings-regret.html

James,

What I don’t quite understand is, how can a bank go broke if it can actually create money?

There isn’t just one type of money. The high street banks don’t create the kind of money which is the liability of the central bank. They don’t have printing presses in their basements running off $50 bills and notes! If they did the directors would face serious jail time for counterfeiting – just like anyone else who tried to do that!

They only issue money in the same way as a casino issues money in the form of gambling chips. Theoretically , if the casino was in good financial shape, those chips could be used as money outside of the casino. Those chips are the liability of the issuing casino. That’s all the banks are doing -except it’s all in digital form. Bank money is the liability of the bank which issues it not the liability of the central bank.

@ James Schipper

Bank A can’t pay those other banks cos it has no money: Peter has no money either, so his debt to Bank A won’t help. Bank A has to get the money to pay the other banks who have Peter’s promise to pay out of the money he borrowed. It gets it from the central bank, as I understand it. The central bank always makes the money available, under normal arrangements, and so the system continues. But the ECB is saying they will not do that under normal arrangements; and there is a threat that they will not do it under ELA either. The bank of Greece cannot do it because there is no sovereign currency: that is, it cannot print money as the BoE can, through the UK government. So Bank A is bankrupt: and so are banks B C and D, since effectively Peter and Bank A have defaulted on their debt to those banks.

I am not very good at this, but that is what I think happens

Fiona.

Correct. Banks have to settle up in real money i.e. currency not Mickey Mouse bank deposits.

The rest of us seem quite happy to use said deposits as a means of exchange and a store of value which I find a bit strange. I suppose the compensation scheme in place does afford some relief.

@ James Schipper

“What I don’t quite understand is, how can a bank go broke if it can actually create money?”

Because a bank creates ‘credit’ money and this is a liability in the balance sheet of the bank. It cannot create money simply to fix a bad bet it made (giving someone a loan whom it turns out did not repay the loan/if a lot of loans go bad the confidence of other banks to lend funds to said bank may be undermined). In all the stock flow consistent models in essesce once the loan is repaid the money through double entry book keeping is returned and the profit made by the bank is on interest/fees.

A pretty good example is here as it follows through with an example about how the interbank system works.

http://www.cnbc.com/id/100497710#.

Capitalistic growth in the eurozone has always been extractive of real purchasing power ( that is the very reason for credit banking in the first place – to engage the population in increasingly more pointless endeavours so as to aid the concentration dreams of the few.

Watch Herzog’s 1982 Film Fitzcarraldo to grasp the true majestic absurdity of it all.

There at the edge of the capitalistic inferno its dark light shines brightest.

Irish car ( steamboat sales) up 30 % in January from a already boomy Jan 2014.

It could be smart guys wishing to trade their paper / electronic deposits for moving metal or more likely credit banks giving their double entry money away so as to artifically increase profits

With every new projection of capitalistic growth / globalisation the population adopts the position of Herzog’s Amazon Indian tribe / slave workforce.

The euro crisis is a break between scenes.

Work has stopped as the actors and technicians engage in a bombastic fight about nothing in particular.

However most of the paid crew are anxious that the show continue despite some animosity between takes.

The tribal element stare blankly at a albeit shocking canvas of deceit which is a natural consequence of the forces behind usury.

@James

No, what the bank has created (as you describe it) is a set of books that don’t balance. Loaned money has to come from somewhere. Either the bank already has it, or it is allowed to get it overnight, but it has to come from somewhere. Even if the money is simply deposited back into the bank making the loan, it has to be there (inc. overnight) first.

“In his autobiographical film Portrait Werner Herzog, Herzog said that he concentrated in Fitzcarraldo on the physical effort of transporting the ship, partly inspired by the engineering feats of ancient standing stones. The film production was an incredible ordeal, and famously involved moving a 320-ton steamship over a hill. This was filmed without the use of special effects. Herzog believed that no one had ever performed a similar feat in history, and likely never will again, calling himself “Conquistador of the Useless”.[4] Three similar-looking ships were bought for the production and used in different scenes and locations, including scenes that were shot aboard the ship while it crashed through rapids. Three of the six people involved in the filming were injured during this passage.” – wiki.

The euro system and wider project has been a vast conquistador of the useless scheme – building these vast highways through the formally very local European hinterland.

Indeed to the point of obliterating all past schemes and standing stones.

Now that we have all these highways to somewhere or nowhere……what happens when filming stops ?

Dear Bill,

I appreciate your descrption that banks are not deposit constrained, but when the system as a whole is short of reserves, is borrowing from the central bank a practical option? I understand that there is no operational prohibition, but I am under the impression that most central banks will only lend from the discount window at a severe penalty, and also look unfavorably at frequent visits to the discount window. Is this an accurate characterization of central bank operation of the discount window?

The reason I ask this question, is if the banking system as a whole is short of reserves, and the discount window is not a practical option, and the central bank is not willing to provide the banking system cash in exchange for financial assets, then the banking system cannot obtain additional reserves necessary to make loans and still meet the regulatory requirements. In such a scenario, the banking system as a whole will hit a regulatory ceiling and cannot create additional loans. Is this correct?

Thank you, Joel

And one other question, please. I understand (but have not verified) that the authorities in Canada require a reserve ratio of zero. Is this true?

Thank you, Joel

Dear Benedict@Large (at 2015/02/10 at 4:31)

You said:

Not quite. It doesn’t have to be there first. It has to be there by the time the payments are cleared. And it never has to be there if the two parties are using the same bank because the bank just cancels the debit and credit out.

The point of the blog was that banks do not create central bank money. They create assets (loan) with an offsetting liability (deposit) and then have to back the liability with reserves, which they know they can always get from the central bank if they cannot get them from other (usually cheaper) sources.

best wishes

bill

Greeks in Greece withdrew money out of banks to pay for the huge burden of taxation, again and again.

There is still this month’s Enfia to pay, but SYRIZA has said this hated property tax will not be levied for this year, 2015.

There is still any backlog to the Xaratsi tax within the electric bill being paid off, up to 12 monthly payments.

The cost of life-sustaining medicine kept going up, so this also drained savings of households.

This has now been reversed by SYRIZA.

As current pensioners, however old, were losing most of their pensions from all sources, savings were dwindling. Age was no safety from the huge tax burden, however poor.

As the Enfia taxed houses, gardens, rubbish pieces of wild forest, inherited unused plots of land, a crappy old village house, even to the cashless, with a nil basic tax allowance, so taxed on each every Euro including being taxed one on top of another: Enfia and Xaratsi and income tax.

People with money, especially the young with university degrees, have emigrated as great as the huge exodus after the second world war.

The economy is as bad as just after the war.

The people left with taxed out of small and medium independent businesses, inherited through several generations, with shops closed in the centre of Athens, like a ghost town. Shops with no lighting nor air conditioning and permanent 70 per cent off sales. Still no customers.

The poor and the middle class have really been wiped out by the Troika’s tax demands.

Businessmen sleeping rough in Athens’ town parks, lost their shop livelihood, which is the bulk of business in Greece through the ages.

This is the reason the bank accounts reduced.

Tax pouring out of Greece to banks that hold Greece’s debt.

Tax that did nothing to alleviate the suffering of the poor, left to rot with no social medicine and little food, if it had not been for the church.

The Troika wanted to tax the church because of the donations coming from around the world so that the poor could be fed.

The Troika demanded tens of thousands of public sector workers sacked, when there was no other work.

People with university degrees, in jobs serving 1 Euro coffees.

1 Euro coffess that the cafe owner had to pay over half in taxes.

This is not a bank run, but a nation, as Mr Varoufakis said, being ‘fiscally waterboarded’.

The bail out never helped Greeks, but only the foreign nations holding debt.

If Greece alone had been in this situation, then we could not blame the EU. But as so much of Europe has exactly this problem, then it is the EU that has inflicted this economic pain whose solution of Austerity does mean people die because of what the EU decide.

The UK has no EU debt, but copies the Troika again and again and people die here because of government decisions, with growing starvation and suicide.

Can SYRIZA please come and rule England.

You give your currency to a bank and it gives you an IOU.(bank deposit)

It deposits your currency in its own currency account with the central bank and gets paid interest on it.

Even when you receive money from the State these days, as a worker or as a benefit, you don’t get currency. You get the IOU from your bank and your bank gets the currency, again credited to its currency account with the central bank.

You can swap the deposit for currency at a cash machine but what you can’t have is your own currency account.

Loans create deposits but not currency which is created by the State.

Most day to day financial transactions are carried out by transferring ownership or title to bank deposits and don’t involve currency.

Final settlement between banks or netting off is achieved by adjusting those bank’s balances of their currency account with the central bank. There is no addition or removal of currency from the banking system unless the State is involved in the transaction.

That’s my current understanding anyhow.

hey neil,

little bit confused by this.

the greek central bank has the power to create euro reserves and deposits independent of what facility the ecb might hve in place. yes or no.

so if there is a euro drain on the greek banking system, the greek banks can do a assett swap with the greek central bank and the greek central bank can create as many euro reserves it likes. yes or no.

so essentially does the greek central bank have infinite liquidity in euros regardless of any ecb facilities.

i suppose if the greek centrl bank has not the power of infinite liquidity in euos, and the ecb is locking them out, to bail out the local banks, they would have to go to new dracmas, and undertake any liquidity op in new dracmas.

and pardon my ignorance, what is the hfsf. are you suggesting the creation of some special purpose vehicle to quaranteen the debts.

Interesting article by Alan Kohler.

Google {Alan Kohler Greece should exit Eurozone ASAP}

Note: Article is behind a paywall unless you access it via Facebook.

Pretty much MMT compliant Id say!

“so essentially does the greek central bank have infinite liquidity in euros regardless of any ecb facilities.”

It has infinite liquidity in its own liabilities, which are the liabilities that *Greek* banks use to settle payments with each other. And for the overwhelming majority of Greeks that is all they care about – particularly as most Greek exports are outside the EU.

You only need ebb facilities when you are going between Member states – when a Greek bank transfers to a German one and vice versa.

You need to think of the banking system as a huge hierarchy – which funnily enough is how the Internet is constructed in wire terms. The Internet gives the illusion that everybody can talk directly to everybody else, but in reality you climb a tree of wires to a trunk and then back down a tree of wires to your target.

So it is with the Eurosystem. It gives the illusion that every bank can talk directly to everybody else (which is what SEPA is – Internet for Euro banks), but in reality the payment clearance traverses a strict hierarchy up via the National Central Bank to the ECB and then back down another NCB to the target commercial bank.

Neil,

So you’re saying that a Greek Euro isn’t the same as a German Euro? If they were both the liabilities of the ECB they would be , but if they are the liabilities of NCBs , but held together on a tight peg, they would not.

So, would it be possible for Greece to simply remove that peg, and let the Greek Euro float?

Petermartin2001,

After Cyprus it was pretty clear that not all euros are treated equally. It is in essence a currency peg — hence the variences in bond yields. But you have to remember that the NCB\’s are essentially a national commercial bank. They can borrow from the ECB, but only as long as the ECB is willing to loan to them. If the ECB cuts them off, then they would have to print their own currency, but it wouldn\’t be euros at that point. The system was designed that way to keep control of more \’profligate\’ members.

I see Yves Smith ( the ultimate progressive insider) grasping for those English law straws again.

Forgive me but whenever I hear the words English law the diggers song starts playing in my little head.

Now those poor stupid English bastards made the mistake of trusting olie and the democracy pretenders while blaming the posh guys in horses desperately destroying the commons in search of yield and rent.

Never understanding the demonic dynamics of usury.

Bill,

“…They create assets (loan) with an offsetting liability (deposit) and then have to back the liability with reserves…”

Please rememeber that reserve requirement in UK or Canada is 0% so there must be something else at play here. It’s simply the fact that left and right side of the balance sheet must be BALANCED . Assets must be backed by liabilities/equity and it creates the need of “funding” once the created deposit leaves the given bank and is not offset by the incoming one, so there is no “hole” in the BS.

Otherwsie it would be counterfeiting