The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Germany has a convenient but flawed collective memory

There is a lot of discussion at present about the historical inconsistency of the German position with regard any debt relief to the Greek government. Angela Merkel has reiterated over the weekend that there would be no further debt relief. Why she is now a spokesperson for the Troika that does not include the German government is interesting in itself. In this context, I recall a very interesting research study published in 2013 – One Made it Out of the Debt Trap – by German researcher Jürgen Kaiser, who examined the London Debt Agreement 1953 in great detail. After becoming familiar with the way the Allies handled the deeply recalcitrant Germany and its massive debt burden in that period, one wonders why the German government is so vehemently against giving relief to Greece. This is especially in the context that the only mistake that Greece made was joining the Eurozone and surrendering its own capacity to deal with a major financial crisis. The ‘mistakes’ of the German nation before the London Agreement have been paraded before us all again with the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp featuring in world events last week.

Jürgen Kaiser is the “co-ordinator of Jubilee Germany – which is “an NGO with about 700 member organisations that strives for a fair and transparent international insolvency framework”. In other words, it analyses and comments on debt restructuring deals from a viewpoint of achieving equitable outcomes with the details being publicly-disseminated.

His 2013 study, published by the – Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) – which was founded in 1925 by the first democratically elected German President, Friedrich Ebert, a social democrat.

The foundation aimed to promote the political and social education of all citizens, to enable talented young people to undertake higher education irrespective of their family circumstances and to enhance international cooperation.

It was banned by the Nazis in 1933 and re-emerged in 1947 and has operated continuously since then with similar aims to its original goals. It is firmly focused on enhancing economic and social justice, promoting socially democratic outcomes, deepening the dialogue between unions and the polity and commenting on global social justice issues.

It is interesting to reflect on these matters given last week’s 70th anniversary of the Auschwitz death camp liberation. Germany, remember, had murdered millions of jews, gypsys, communists, homosexuals and others they considered deviant.

They had waged war on Europe and caused untold material and emotional damage.

Greece has done nothing of that. Indeed, Germany inflicted massive and cruel hardship on Greece during its Nazi era.

Further, Germany was sovereign in its currency at the time while Greece is not.

It is also rather far-fetched to call the Greek bailouts (the two already in place) – debt relief for Greece. As I discuss below, Greece was unable to use very much of the bailout funds to expand domestic spending and actually improve their economic plight.

It is more accurate to say the bailouts were to the benefit of the French and German banks which were exposed to the risky Greek public debt.

Jürgen Kaiser’s research is very interesting in this context.

He notes that on February 27, 1953, the London Debt Agreement was signed between the various nations that had been at war with each other during the 1940s.

The Agreement:

… relieved … [Germany] … of external debts to the sum of nearly 15 billion Deutsche Mark – i.e., about 50 per cent out of a total external debt of 30 billion Deutsche Mark, consisting of both pre- and post-war debts. This debt relief repre- sented roughly 10 per cent of West Germany’s GDP in 1953, or 80 per cent of its export earnings that year.

So it was significant relief in the context of the state of the economy at the time.

Kaiser concluded that the:

London Debt Agreement, with its very generous conditions, made a significant contribution to West Germany’s post- war »economic miracle« of the 1950s and 1960s, and to a speedy reconstruction of the war-torn country.

The motivation for giving Germany the relief was to stabilise “the country both politically and economically as quickly as possible”, especially in the context of the growing Cold War tensions.

The Allies had learned their lesson from the faulty Versailles Treaty at the end of World War I, which made “the mistake of burdening a defeated war enemy with an economic tribute, that would destabilize it for decades and thus pave the way for political radicalisations of all sorts”.

The rest of the Research Paper provides significant detail about the Agreement and how it might represent a model for current public debt restructuring.

But Jürgen Kaiser makes another very significant point:

Surprisingly, little knowledge about Germany’s debt relief is to be found among the broader public in Germany or in former creditor countries.

Groupthink has a tendency to suppress information and public debate, which might prove inconvenient to the current orthodoxy. Why did the Nazis lock up the dissenters, for example.

The suppression also creates space for historical revisionism.

It is now convenient for Germany to hold itself out as the paragon of virtue and frugality so that it can demonise other nations such as Greece.

The language of morality has been prominent in the way leading German politicians have spoken of Greece.

We have read that Greece “wasted potential savings in a spending frenzy” that “Germany committed itself to the virtuous path …” and the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble told the press before a two-day summit in Brussels in March 2010 on whether there should be Community support for Greece, that “an automatic system that hurts those who persistently break the rules” was needed to punish the “fiscal sinners”.

So it is no surprise that the Germans would not want to educate its public widely on details regarding the London Debt Agreement 1953. Would the public’s reaction to Greece be any different if it understood how their nation was treated generously by the Allies who had suffered grievous losses under the inhumane actions of the German war machine?

The other point lost in the debate is the nature of the bailouts that have loaded Greece up with debt. If a party provides a service to another which has no chance of success then who is liable?

The Greek bailouts

The first mistake the European policy makers made was to claim that excessive government spending had caused the crisis.

In the early days of the collapse, the news media was full of stories of lazy Greeks who didn’t pay taxes and a lax government, spending beyond its means. This was meant to explain why private bond investors were pushing up public borrowing costs.

But that occurred because the bond investors had realised that Eurozone governments were at risk of insolvency because they had surrendered their currency sovereignty.

The real cause of the crisis was the spiralling and unsustainable private debt build-up and the exposure of the European banks to that debt.

This was pushed quietly to the background by the Troika and only occupied their minds when they forced the Spanish, Irish and Greek taxpayers to foot the bills necessary to keep the big French and German banks from failing.

The fact that these ‘bailout loans’ were added to the outstanding sovereign debt of these nations only exacerbated the situation.

Further, there was no evidence that government spending among the Member States was in any way ‘out of control’. Greece, alone was running larger deficits than most. But Spain and Ireland were exemplars of fiscal prudence as defined by the nonsensical SGP rules.

The other aspect of the bailout loans that is not often understood is the incompetent behaviour of the Troika partners themselves.

When the European Commission was faced with nations unable to fund themselves but with pending liabilities maturing, they turned their focus to bailouts.

A new European bully formed, the so-called Troika (the European Union, the ECB and the IMF), to spearhead the austerity push.

Once again the unelected and unaccountable IMF felt its role was to trample on the democratic rights of citizens in Greece and elsewhere.

While these interventions initially protected Greece and other nations from insolvency, they imposed destructive conditionality, which made it impossible for the nations to grow.

The first major bailout came in May 2010, when Greece was given a three-year €110 billion loan from the Troika with strict conditions attached. The austerity package was breathtaking in its harshness. Greece was compelled to reduce its deficit by 15 per cent of GDP within three-years, which was an impossible task.

The IMF claimed that the fiscal policy changes were “frontloaded with measures of 7½ percent of GDP in 2010, 4 percent of GDP in 2011, and 2 percent of GDP in 2012 and 2013, each, to turn around the fiscal position and help place the debt ratio on a downward path”.

It was obvious that the austerity plan would, in fact, increase the deficits given the loss of tax revenue that would accompany the output and employment losses.

The Troika demanded that public sector pay be cut by around 18 per cent and pensions cut by 10 per cent, that wages and pensions be subject to a three-year freeze, that taxes on fuel, alcohol and tobacco be increased by 10 per cent and across-the-board VAT increases of 2 per cent be imposed, among other measures.

When announcing the terms of the bailout to the Greek people, Prime Minister George Papandreou wore a dark purple coloured tie, the colour that Greeks wear to funerals. But his days were numbered. Soon after, the Troika got rid of Papandreou and put one of ‘their men’ into the role, the central banker Lucas Papademos. It didn’t matter what the people who vote might think!

Key personnel in the Troika were unflinching in their claims that austerity would be good for Greece.

Soon after the bailout was pushed onto Greece, a centre-left Parisian daily newspaper published an interview (July 8, 2010) with ECB boss Jean-Claude Trichet – Jean-Claude Trichet: Interview with Libération.

He was asked whether the austerity plans “pose the risk of killing off the first green shoots of growth” (Quatremer, 2010), He replied:

It is an error to think that fiscal austerity is a threat to growth and job creation. At present, a major problem is the lack of confidence on the part of households, firms, savers and investors who feel that fiscal policies are not sound and sustainable. In a number of economies, it is this lack of confidence that poses a threat to the consolidation of the recovery. Economies embarking on austerity policies that lend credibility to their fiscal policy strengthen confidence, growth and job creation.

The IMF had the audacity to put numbers to this Ricardian nonsense and predicted that by 2012, Greece would return to increasingly robust growth. The IMF (2010: 8-9) predicted growth would follow a “V-shaped pattern” and that:

… the frontloaded fiscal contraction in 2010-11 will suppress domestic demand in the short run; but from 2012 onward, confidence effects, regained market access, and comprehensive structural reforms are expected to lead to a growth recovery. Unemployment is projected to peak at nearly 15 percent by 2012.

[Reference: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2010) ‘Greece: Staff Report on Request for Stand-By Arrangement’, IMF Country Report No. 10/110, May].

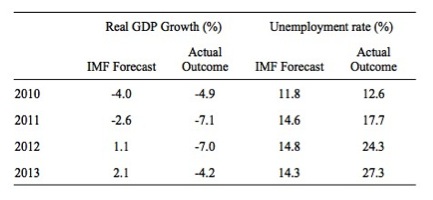

The following Table (drawn from my soon to be published book on the Eurozone crisis) shows the IMF growth forecasts against the reality. The forecasts they had used to justify their harsh austerity package for Greece were very inaccurate.

IMF forecasts for Greece and reality

Source: IMF (2010), Eurostat.

Moreover, the actual outcomes were more in keeping with what a reasoned assessment, which was uncontaminated by neo-liberal ideology, would have suggested.

Cuts that deep and that quick were always going to devastate both public and private spending and lead to a Depression with very high unemployment. By April 2014, the national unemployment rate in Greece remained at 26.5 per cent.

Any other professional practitioner would be liable for the payment of significant damages if their judgements (that were acted upon) we so inaccurate and so damaging. The IMF and its Troika partners should therefore be liable to the Greek people for their incompetence in this regard.

Why isn’t that part of the discussion and public debate?

And remember the sequel to this story. As the Troika were busily imposing austerity on beleaguered European nations, such as Greece and Portugal, the IMF consistently claimed that their ‘modelling’ showed that if governments cut their fiscal deficits quickly, private sector spending would respond and growth would soon return.

In the IMF’s October 2012 World Economic Outlook, we learned that their past recommendations for fiscal austerity in Europe, which conditioned, for example, the harsh terms embedded in the Greek bailout packages, were based on ‘modelling errors’.

[Reference: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2012) World Economic Outlook (WEO) October 2012, Washington D.C.].

They admitted (page 43):

… that actual fiscal multipliers have been larger than forecasters assumed.

Fiscal multipliers tell us what will happen to total spending (both public and private together) for every extra $1 of public spending.

The IMF had assumed that they were very low (below 1) so that cutting public spending would actually lead to higher total spending. In October 2012, they admitted that the ‘multipliers’ were well in excess of 1, which means that if the government cuts spending by 1 Euro, the total decline in spending and output will be well in excess of that.

The reality told us that would be the case. More credible economic modelling (such as that by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists) told us that would be the case.

But the neo-liberal biases in the IMF models simply refused to allow that to be the case because it would have been inconvenient to their ideologically motivated desire to cut deficits and reduce the size of government.

So the combination of some shoddy spreadsheet manipulation, incompetence from the IMF, and the usual European Groupthink justified policies that have led to millions of people losing their jobs – unnecessarily!

In June 2013, the IMF released a suite of new reports on Greece. At the press conference accompanying the release the head of the IMF Greek Mission Poul Thomsen was asked “Is it true that the IMF admits mistakes on the Greek bailout?”.

[Reference: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013b) ‘Transcript of a Conference Call on Greece Article IV Consultation’, Washington, D.C., June 5, 2013].

Thomsen replied:

Sure. There is in this bundle of papers, there is a discussion of the past and, in the context of the Article IV Consultation, a full report … And, sure, in reviewing what we have done the whole time, there are certainly things we could have done differently. We already had that debate six months ago on these multipliers and that if we should do it again, we would not use the same multipliers.

The arrogance notwithstanding, the accompanying report (IMF, 2013b) admitted that the IMF had altered its own rules in order to provide the bailout.

[Reference: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013c) ‘Greece: Ex Post Evaluation of Exceptional Access under the 2010 Stand-By Arrangement’, IMF Country Report No. 13/156, June].

It was clear to them from the outset that the austerity program would not reduce the Greece’s public debt ratio, which was one of four criteria that the IMF rules dictate must be satisfied in order to provide funding.

They proceeded not as a result of any concern for what the austerity would do for Greece but “because of the fear that spillovers from Greece would threaten the euro area and the global economy” (p.10).

Defending the interests of international capital has always been a priority of the IMF even if the welfare of ordinary citizens is compromised.

Extraordinarily, the IMF also admitted that in retrospect Greece actually failed to meet three of the four criteria for funding (p.29), which indicates how poor the initial assessment was, in part, because the “negotiations took place in a very short period of time” (p.49).

The IMF has a history of parachuting officials into nations who within a day or so come up with radical structural adjustment programs, which ravage the local economy.

The neo-liberal free market paradigm is seen as being a ‘one-sized-fits-all’ solution, irrespective of the circumstances.

Finally, the huge IMF forecasting errors in relation to Greece were not one-off incidents. While forecasting errors are a fact of life, the IMF and other major neo-liberal inspired organisations produce systematic errors, which means they consistently make the same errors, which are easily traced to the underlying ideological biases, which shape the way they create their economic models.

Thus, the IMF typically overstates the benefits of austerity and understates the costs. Further, they also overstate the inflationary impact of fiscal deficits.

Each systemic error reinforces their free market approach. Yet, each systematic error also demonstrates the poverty of that approach.

As we noted earlier, any major professional group exhibiting this level of incompetence would be stripped of their right to practice and open to major legal suits for damages and imprisonment.

In the case of Greece, the damage caused by the IMF errors were massive.

Some IMF officials, at the very least, should have gone to jail given that the damage that the institution has caused dwarfs that of fraudsters such as Bernie Madoff who was sentenced to 150 years imprisonment for his criminality.

As economic and social conditions deteriorated in Greece, it became obvious that the country would not be able to meet its on-going liabilities without further financial assistance and would be forced into default by March 2012.

After an emergency European leaders’ summit in July 2011, the 10th in 18 months concerning Greece, a second Greek bailout package was proposed. This bailout was the first to suggest that the private banks and other private bond holders would provide some of the debt relief.

The so-called ‘haircut’ or private-sector involvement (PSI), proposed that investors would either roll over their stock of maturing Greek government bonds or sell the bonds back to the government at a discount.

In return, the Greek government agreed to even harsher austerity measures including further tax increases, more public sector job cuts, a 20 per cent cut in workers’ wages, pension cuts and reduced trade union rights.

In September, the Greek parliament passed some of the tax increases but civil unrest was mounting. On October 19, the day before the vote on the rest of the austerity measures in parliament, a national strike began supporting large-scale protests in Athens. Amidst violent riots outside the parliament, the Government passed the bill.

On October 26, 2011 the details were fully worked out between the parties. The Troika would extend €130 billion to Greece in return for more austerity and all private Greek government bond holders would be invited to accept lower yields and discounts on the face value of their assets.

The total bailout sum included an estimated €30 billion in revenue, which the Troika hoped Greece would get from the large-scale privatisation plan it had agreed on as part of the first bailout.

Further, some 40 billion euros of the bailout sum would go to buying back debt (safeguarding banks) or recapitalising zombie Greek banks. In other words, the interests of capital were privileged.

Virtually no new funds were made available to support spending in the Greek economy to stimulate employment. Further, for all the angst surrounding the negotiations, it was estimated that the deal would not provide any significant debt relief anyway.

While the political leaders and the ECB did not refer to this as a default, it was clearly that. The German government once again dominated the negotiations by constructing the plan, which forced the private banks to take some of the loss. The French and ECB had been opposed to such a move.

All parties finally agreed to the deal on February 21, 2012 including the 53.5 per cent ‘haircut’ on the face value of any bonds held. The Troika demanded that the Greek government set up a special ‘off-budget’ escrow account which had to be prioritised and contain enough cash at all times to service its liabilities.

The Germans and French had at one stage proposed that a European Commissioner take over running economic policy in Greece. Facing increasing hostility, the Troika decided to create a ‘task force’ of inspectors who would rough ride over the democratic process to make sure that the Troika got their pound of flesh.

Later in 2012, the Greek government was forced to ratchet up the austerity cuts in order to receive the next instalment from the Troika.

By June 2013, the Government closed its public broadcaster, marking a further blow to democracy. Greece was now, more or less, a German colony.

The reality was that Greece could never fulfil its obligations under the agreement given the harshness of the austerity measures, which guaranteed that it would remain in Depression for many years to come.

Even with the reduced debt burden, insolvency was a continual threat and increasing poverty was a certainty.

So after reading the research study by Jürgen Kaiser on the way the London Debt Agreement gave oxygen to the shamed Germans, one wonders why history has been forgotten in the way the Greeks have been dealt with.

Their only mistake was joining the Eurozone and surrendering their own capacity to deal with the financial crisis on their own terms. When stacked against the crimes of Germany in the 1930s and 1940s you can only wonder how the Germans can justify their position in this matter.

Conclusion

It is clear that Germans have convenient but very flawed historical memories.

They focus on the 1920s (Wiemar) and forget the early 1930s recovery (Keynesian-style).

They focus on the lazy Greeks and puff themselves up with the self-importance of their perceived frugality and forget or don’t even know about the London Debt Agreement 1953.

But neo-liberalism has actively tried to suppress historical understanding and when facts are inconvenient they seek to redefine them.

I will write in coming blogs about the growing democratic fightback against austerity and neo-liberalism. But it is now clearly evident in a number of jurisdictions and levels of government.

Just as social democratic forces emerged in the late C19th to combat the growing excesses of an unfettered capitalism, we are once again witnessing people-power.

What form it will take and how successful it will be remains to be seen. But it is happening.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

So Germans should pay some sort of financial penalty for sins committed not by present day Germans, but almost exclusively by their parents and grandparents? How far do we take this: is Russia entitled to compensation from France for the damage done to Russia by Napoleon, e.g. the destruction of Moscow, and the tens of thousands of Russian deaths? There comes a time when “forgive and forget” is in order.

Well said Bill.

‘But Jürgen Kaiser makes another very significant point:

Surprisingly, little knowledge about Germany’s debt relief is to be found among the broader public in Germany or in former creditor countries.

Groupthink has a tendency to suppress information and public debate, which might prove inconvenient to the current orthodoxy’

On this point, there is an interesting comment on a post at Naked Capitalism by a German named Patrick Schmidt (perhaps an Irish German!)

‘I saw the following on German TV six days ago. A highly popular program ‘Hart, aber fair’ debates current issues with prominent German personalities taking either pro and contra sides. Last Monday evening, the topic was ‘Should Greece pay back its debt’. When the TV moderator presented the fact that Germany was forgiven 90% of its debt in 1953, Bavaria’s finance minister Markus Soder, who was demanding Greece pay back ever cent, suddenly went into denial and then in panic stated that the international lenders had continually given Greece many opportunities to lighten its burden with new loans and extended payback periods.

Whether he was right or not was not important. Far more important was the perceptual change in the general German public mind. At the beginning of the broadcast, the majority of Germans felt that Greece should pay back its debt, but upon learning about their own history, found themselves without any more valid arguments. A classic case of cognitive dissonance.’

The program is here, but it is as I said at NC, all Greek to me:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8Vuf1n1_H4

The Naked Capitalism post is here:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/02/syriza-walks-back-initial-defiance.html

So Ralph, I guess if the Greeks just wait long enough, Germany should ‘forgive and forget’?

Why put it off?

Dear Ralph Musgrave (at 2015/02/02 at 16:10)

You have fallen into the German narrative.

Who said anything about Germans having to pay anything?

The discussion is about whether the Greeks should pay. The ECB has infinite resources to buy all the debt and write it off without any further consequences for Germany or the other nations. Only the Greeks would be better off. But then only if they exit the Eurozone.

best wishes

bill

Germany is very much a colony as it it forced to engage in aggressive mercantilism.

It accepts the rules of the game…..but who exactly makes the rules.

All most all of us were not born during the 30s

Why should we engage in historical monetary transactions of this nature.

I am with Dieudonne is so far as he rejects a hierarchy of suffering as such moral debates descend into endless cascades of bullshit.

I guess he was locked up because he was causing a union of former conservative Catholics with the Arab street……this would begin to destroy the Zionist /Jewish establishment – so could not be tolerated.

Characters such as Dieudonne would always react against the establishment….it so happens the elite are essentially of a Jewish / masonic clic who impose artificial scarcity on the populous so as to maintain concentration of power.

A union of classic French nationalists such as Alain sorrel and Dieudonne is far more likely to be successful in France then in Germany given the particular German disposition of being herded into killing zones.

France is now a tinderbox as people are finally begibibg to react against decades of mind control / political correctness and health fascism.

If debts cannot be repaid they will not be repaid. Debts, in the commercial world, usually end up being settled. If they aren’t settled it is nearly always because debtors cannot pay rather than because they have chosen not to pay. There is a well recognised procedure , in civil law, recognising this truism, which can end up in the bankruptcy of the debtor if a suitable settlement with creditors cannot be satisfactorily negotiated.

Bankrupting a country, like Greece when it gets into financial difficulty, however, is not a political option. Unless we want to start another war between Greece and Germany that is! So what are the options? Apart from carrying on, in both senses of the term, in the the present irrational manner there is only one. If Germany (plus other countries such as Holland who also own Greek debt) requires Greece to repay its debts, Germany has to recognise that Greece has to pay in something other than euros, at least not directly, as it clearly does not have anywhere near enough and has fewer now after the application of the supposed economic remedy (punishment?) by the troika than it had previously.

Therefore, it has to pay in real goods and services: Tourism. Olives. Feta cheese. Ouzo. Shipping. Whatever Greece makes, does and sells, Germany needs to buy to enable the debt to be settled. And it needs to buy more from Greece than it sells to Greece. That way Greece ends up with the euros, which pays the Greeks for growing the olives, running the tourist hotels, making the cheese etc . This enables the Greek economy to provide jobs for the unemployed, improve its Government’s tax revenue base, grow its economy, and also enables the Greeks to service, and eventually settle, their German debts.

The same naturally goes for Spain, Italy and even France. In other words, German debts get repaid when, and only when, Germany decides to accept real goods and services instead of euros. This in turn means that Germany has to run an economy more along the lines of the UK and the USA economies and import more goods and services than it exports.

Germany remains under allied occupation, and is not sovereign. Further, National Socialism was direct rebellion against this very system of international finance. This is not a fair assessment of Germany. They cannot take any other side, both for practical reasons and ideological reasons. If anything, it is time to stop demonizing the third reich in such black and white ways, and be mindful that Germany then had the same grievances as many today. MMT is necessary not simply for practical reasons, but to insure this madness does not yet again result in a terrible war.

Ralph, “So Germans should pay some sort of financial penalty …..”

What would it mean if Germans did “pay some sort of financial penalty”? They have less money, right? And they’d have to work harder to make it up? So, this just means they’d consume less so and they’d have to export more. Instead of having a 7% surplus it would maybe go to 10%. That would only make things worse in the EZ. Therefore, we conclude that making Germans worse off isn’t what is needed.

We actually need them to be better off to solve the problem. Lucky Germans! That means they need to run deficits, consume more of their own stuff and more that is made by Greece and Spain too. Imports are a net benefit. Exports are a net cost. Remember that from Warren Mosler’s book? The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds.

From a social credit perspective capitalism is usury.

But people must sit inside this cone of silence that we call democracy (British style)

Only a fellow Jew such as Jacob Cohen when he speaks of the French state being a vassal for CRIF dinners club policy decisions can criticize such dark absurdity.

All gentiles are prevented from reacting to such malice.

We will soon come to fear ( if not already) the thought police bursting through our doors.

The policy is obviously to destroy the last vestiges of the peasant class much like how it was first destroyed in Britain all those centuries ago.

We will have the serfs and international men of mystery and nothing in between.

Mmt full employment policy is obviously at the vanguard of this movement.

To have a large mass of consumerist wage slaves without access to capital or land.

You can clearly see this policy action in Ireland today with the 20 % deposit restriction on mortgages

Deposit restrictions never stopped a housing bubble.

As land and housing is no longer a national affair ,people with accesses to credit outside of Ireland will buy up all the land and charge a rent on it.

The object of the game is to destroy us.

And it is working in a spectacular fashion.

Not a doubt in my little head now , this is some sort of strange and twisted undeclared holy war on landed tradition.

On the home and the hearth.

As Alain sorell states : under the ancient regime you would not be sent to the Bastile for stating the King is the King.

But under today’s system …………

Under a republic there is no intermediation between the citizen and the state.

Except of course for the organised community.

The French state must bow to its dictates like all the others.

So by definition France is no longer a republic.

Dear Dr. Mitchell,

Would you please explain the meaning of capitalizing a bank? I take it that these are funds or assets provided by the bank’s owners for which they receive shares of stock.

I mean what is the function of a bank’s capital as compared to its central bank reserves, which you have explained are not loaned out but exist merely for the purpose of assisting the central bank to clear intra-bank transactions.

Where does a bank’s capital reside? What role does a bank’s capital play in its ability to loan money, which it does, as you have taught us, by creating an account for the borrower and changing the bytes shown in the account’s amount variable from zero to the amount of the new loan.

This also leads to the question, if reserves merely expedite transaction clearing, then what is the meaning and function of so-called excess reserves, the creation or destruction of which seems to be the way central banks try to influence the money supply? What difference does it make if the central bank pays interest on these reserves?

Finally, on another matter, I notice many economists asserting that we are at the zero-lower bound, referring, they say, to the impossibility of paying negative interest rates. I read, however, that the Swiss central bank has set interest rates to be negative, which I guess means banks charge depositors for holding their funds instead of paying interest on the accounts. Why can’t other banks do that?

Thanks.

The Germans of course are not alone in having a poor economic memory, but given their history probably should have a better one.

There is too, I’d argue, racial/ethnic bigotries that underlie the German position, and seem to underlie German views of Southern Europeans in general. Combine this with seemingly German propensity to put ideology above reality. The German government has to know that things on some level are unsustainable and that the outcomes that don’t match the predictions are not the Greeks fault, but they can’t seem to let their flawed ideology go even in face of the evidence.

Its not that people today have a poor memory , they have no memory of balance in society.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=r0LZCkxfE9M

It seems that the Greeks do not owe Germany anything. Early on the banks of Germany and France were crashing under bad debt a lot of it owed by Greece, Ireland, Spain and etc. Let’s not forget little Finland who told the banks to get hosed.

In the US we just bailed out our “to big to fail” banks.

In Europe they figured out that if they had the Troika lend a lot of money to Greece they could get the Greeks to turn it over to the insolvent banks in France and Germany. Hence the Troika bailed out the French and German banks with a loan to Greece. Where does the German government come in but with a lot of blather(neo liberal, uptight Christian guilt about sin and guilt.)

Now most of the money the ECB gives to Greece is given back to the ECB to service the interest.

Okay I’ve gotten myself twisted up a bit.

Then comes austerity. This has ruined Greece’s ability to grow and reduce unemployment making it impossible to pay its so called debt.

Yanks Varoufakis asks: when banks make bad loans is it only the borrower’s responsibility?

Europe was afloat with bad housing loans as was the US. The banks couldn’t get enough of them to fuel the shaky investment instruments, derivatives, cdo’s, and so many more creative ways to rip off the banks and investors.

Further more the money comes from the sovereign issuer of euros, the ECB- not Germany.

So to paraphrase Bill, what’s Germany got to do with the Troika. Maybe they will shut up and let the EU and the ECB and IMF deal with the problem with Greece, and hopefully Yanis will tie them in knots. And don’t send him any functionaries either!

To Ralph Musgrave and to anyone that has the same opinion

So aside from the Greeks at that time that had to deal with what Germany did and trying to get past what Turkey done previously to them and would do again. What “forgive and forget” did the Greek children and grandchildren get when they had to pick the pieces up of a country with destroyed infrastructure and resources and no money and gold in the countries coffers because Germany of that day destroyed and took it. And then trying to go after that debt stolen gold and historical artifacts decade after decade of a more powerful country that refuses to give it back.

What about the Greeks that survived having to deal with physical and psychological damage once again and their children having to witness it. Or the grandchildren seeing the effects. Because it does not just go away. When the generation that experienced it dies or gets old. It takes more than a couple of generations to forget about war and genocide committed against once family and country. It has an effect and shapes the descendants as well. Especially when there is no sense of justice and change and understanding by the perpetrator. Only then can a people forgive.

But as Bill said this is not about Germany having pay anything.

It was brought up by people like Jürgen Kaiser, French economist Jacques Delpla, German professor of economic history Albrecht Ritschl and people in Greece to ask whether or why Greece should pay. To show the hypocrisy of the German stand on the issue. And to ask for a more fairer approach to the issue.

I meant Iceland not Finland.