In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

A fiscal collapse is imminent – when? – sometime!

Sometimes I wonder how it is that a bright person can stick to a story for so long when the evidential record is so contrary to the predictions that their story keeps forcing them to make. Then again the predictions are often couched in terms of “might” and “We don’t know what will trigger such a wave of selling” (don’t know!) and “interest rates would shoot up” (would!) and “if the number of people trying to sell them surges” (if) and “inflation would erode” (would! again). So nothing concrete – just a series of assertions. So such a person is never really confronted with the reality that they know “shite” (a word I read in a book by an Irish author I have just finished – In the Woods by Tana French – recommended). This sort of denial is an overwhelming characteristic of the mainstream of my profession. I would love to be proved wrong if private households and firms do turn out to be Ricardian and fiscal austerity leads to a boom with full employment. I would abandon my MMT leanings within a flash and get on the prosperity bandwagon. Why is it that the mainstream, which has the dominant influence on policy makers – and therefore get to see their theories applied in the real world – not adopt a similar position. The predictive capacity of their paradigm is next to zero!

Consider this quote:

Since the mid-1990s the government debt has followed an explosive path, and policymakers and economists have come to think that there is no more room for fiscal expansion, which had been the major policy tool to cope with the protracted slump throughout the 1990s,

Warm up question for tomorrow’s Saturday Quiz – Where did this person receive his PhD from? Answer: Guess!

The quote comes from a paper – Fiscal Consequences of Inflationary Policies – written by Japanese economist Keiichiro Kobayashi, who is a Senior Fellow of Research Institute of Economy, Trade & Industry, (RIETI) and holds various other appointments.

He is a fairly prominent author and commentator in Japan. Here he is, presumably illustrating graphically how much he knows about macroeconomics, which is not much judging by the distance being demonstrated.

Anyway, in that paper, Dr Kobayashi outlines a model, which augments a model that Paul Krugman used to make embarassingly wrong statements about the Japanese economy in the late 1990s – please see this blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more detail on that.

In this model, we read that in an economy which “is comprised of infinitely many representative households, each of which lives forever”, that “the government neither invests nor consumes but uses the fiscal surplus collected from the people to redeem government bonds”

Logical question: Why does the government issue bonds if it doesn’t spend (even in a mainstream model)? Answer: Because he has to assume this to get the results that he desires.

Anyway, in this model, Dr Kobayashi concludes that:

The policy implication of the above argument is that the Japanese government should undertake a more aggressive fiscal (and monetary) expansion today in order to escape from the liquidity trap. But huge fiscal deficits and the government debt, which is building up at an explosive rate, are also extremely serious problems in the Japanese economy.

When was this paper written? Answer: 2002.

In that paper we also were introduced to familiar ways in which mainstream macroeconomists proceed.

The optimal value of the fiscal deficit may be smaller than the currently prevalent one; although it depends on parameter values, it is possible that fiscal consolidation today that exacerbates the current GDP gap may be the optimal policy, if the future cost of fiscal adjustment is expected to be too large.

I cannot assess the relevancy of the above implications quantitatively, since the functional form and the parameter values for the social costs of fiscal adjustment are not known in empirical studies. But as long as fiscal adjustment is socially costly, it is necessary to consider the trade-off between elimination of the liquidity trap today and costly fiscal adjustment tomorrow.

But of-course, even though he admits his model has very little empirical relevance (“the functional form and the parameter values” are effectively unknowable – that is, assertions reflecting the bias of the author), the reader is already confronted with the assertions as if they are facts.

For examples, consider the two quotes – one earlier in the paper and the other appears somewhat later. The reader reads that Japanese government deficits and debt are “building up at an explosive rate” and “are also extremely serious problems in the Japanese economy”. That is, facts are alleged without recourse to the data.

So by the time the reader reaches the qualified section – where the author “cannot assess the relevancy of the above implications quantitatively” – the message is already been planted in his/her mind – deficits and debt are exploding and are problems never mind some analytical niceties!

We will come back to this later and see some evidence. Considering evidence is always a sobering experience.

Anyway, Dr Kobayashi (who is really representative of the mainstream view on these matters) gave an interview (April 9, 2012) – Build up foreign currency assets to ease pain of bond market crash – to the Asahi Shimbun, which is one of the leading daily newspapers in Japan and offers an on-line news service on Asian and Japanese issues in English.

It was a long interview but the message was clear. Japan is “headed toward a fiscal catastrophe” and Dr Kobayashi joined the chorus of “apocalyptic warnings”. The journalist had the audacity to say (apropos of the theme of this blog) in her introduction that the:

apocalyptic warnings, which might have been seen as scaremongering a while ago, are now getting some serious attention these days, perhaps because of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The shelves of bookstores are overflowing with titles containing two words–crisis and Japan.

When asked about Japan’s fiscal health, Dr Kobayashi said:

Japan is in a situation where it can no longer pay back its excessive debt with tax revenue alone and must keep piling on new debt to pay off old debt. In other words, its debt is snowballing. Actually, however, prices of Japanese government bonds, or the government’s IOUs, will tumble before a fiscal collapse or the government’s default on its debt.

No currency-issuing government would think of paying back its outstanding debt with tax revenue. Moreover, if it wanted to the Japanese government could authorise the Bank of Japan (which might require some changes in rules and conventions) to retire all the outstanding national government debt as it matures.

A few computer entries would accomplish that – not that I am recommending such an action. But within the parameters of the monetary system it is possible.

Expressions like “excessive debt” demand a definition. Excessive in relation to what? Time? Some threshold? For a currency-issuing government which can always meet its nominal obligations in that currency there is no financial sense that can be made of the term “excessive”.

In an institutional environment where the government insists on matching their net spending (budget deficits) with debt-issuance into the private sector then we would define excessive debt as being reached when nominal aggregate demand (driven by the deficits) had outstretched the real capacity of the economy to respond in real terms (that is, by increasing production of goods and services).

But that definition has nothing to do with the level of debt (scaled against GDP or not). Rather, it would relate to the excessive spending.

Clearly, in the context of Japan over the last 20 or more years – with deflation rather than inflation being the concern – there is no sense that the budget deficits are “excessive”.

Further, words like “snowballing” are often giveaways – to generate concern and a sense of proportion that is not justified by recourse to the evidence.

As we will see the evidence is very unkind to Dr Kobayashi, even though he does not seem to recognise that.

He then said that the crisis will come because:

… people start thinking that the Japanese government may be unable to pay back its debt, they decide to cash in–meaning sell off–the Japanese government bonds they hold before their prices fall. The price of any product sinks when there are more sellers than buyers. That’s true for government bonds as well.

Government bond prices would crash if the number of people trying to sell them surges. We don’t know what will trigger such a wave of selling. It could be the debt crisis in Europe and it could be the political situation in Japan.

What would lead “people” to think the Japanese government, which has issues the currency “may be unable to pay back its debt”. Where is the precedent for that? It is obvious that “people” clearly understand the government is totally solvency and Japanese government debt is risk-free.

The bond tenders are oversubscribed each time and have been that way for years despite the doom merchants predicting that the default was just around the corner. The road seems to be endlessly straight!

Who is going to buy the debt if such a crisis occurred? Well, the Bank of Japan could buy it all and guarantee a constant yield if it desired. The government can completely control the prices of the bonds it issues if it so wishes.

Dr Kobayashi either doesn’t know that or refuses to admit it.

But, instead, he tells the interviewer that “(i)nterest rates would shoot up, triggering inflation” and when asked why “tumbling government bond prices cause inflation” he replied:

There are various theories to explain that. One says that massive selling of Japanese government bonds would eventually force the Bank of Japan to buy a large amount of bonds by printing money. That would increase the money supply and thereby cause inflation.

So tracing back – he now says that the Bank of Japan can buy bonds any time it wants so the bond prices can be stabilised at whatever level the central bank desires which means, in turn, that yields can be stabilised. That is, “interest rates would … [NOT] … shoot up”.

But also note that the “theories” that allegedly explain his fears are none other than the Quantity Theory of Money and the concept of the money multiplier.

Central banks have been purchasing huge quantities of bonds in recent years and money supply growth has been relatively subdued. Further, there is no necessary relationship between the “money supply” and inflation.

If the central bank purchases the bonds, the funds go into bank reserves. If people then choose to change their portfolio behaviour and liquidate and spend up on goods and services, then government deficits would fall anyway and bond-issuance (under current institutional arrangements) would decline with predictable effects on bond yields (down).

Moreover, unless the economy is at full capacity, then there is plenty of real space for increased nominal demand.

This is all, of-course, notwithstanding the Basel III requirements which will see an increased demand for government paper not less. It is likely that in certain nations there will not be enough government debt!

Apparently, Dr Kobayashi predicts that bank credit would then dry up because the banks would lose cash on their government bond holdings. He tried to draw an analogy between the 1990s collapse of the real estate market which saw bank lending curtailed as banks made huge losses to his speculative collapse in government bond prices:

… banks could start tightening up their lending standards and cutting off credit lines. That happened after Japan’s economic bubble burst in the early 1990s. At that time, banks saw their loans to businesses sour. For banks, loans are assets. Many Japanese banks now hold government bonds as assets. This time, this type of assets would depreciate. If banks begin to shut off lines of new credit and call in loans, businesses would find it difficult to get the money they need. The economy would then slip into serious recession.

Central banks could not easily prevent the real estate values from collapsing in the same way they can manage the price of government bonds (and their yields).

He was asked whether the solution is “through tax increase and spending cuts” and responded:

That’s right. And these policy measures must be taken quickly. The government’s debt keeps growing. Putting off the actions needed for fiscal rehabilitation would only make the process even more painful. Several years ago, it was said that raising the consumption tax rate to 15 percent would put the nation’s fiscal house in order. Now, some economists say the rate needs to be raised above 30 percent to cure Japan’s fiscal ills. I believe a consumption tax hike to 25 percent would do the trick if it is combined with a sharp reduction in social security spending.

So in the previous quote he was concerned about a “severe recession” occurring yet advocates policies that would certainly plunge the Japanese economy back into recession. The same thing happened in 1997 when tax increased put a stop to the emerging growth and held the Japanese economy back for the next 5 or so years.

As I will show later – when the Japanese economy is stimulated into growth via budget deficits debt ratios fall.

The interviewer was, in fact, somewhat challenging. The following exchange occurred which really tells you about Dr Kobayashi credentials to be commenting on this sort of topic:

Q: For all the dire warnings about Japan’s impending fiscal disaster, however, Japanese government bonds have not crashed yet. Nor has there been any panic in the market. Why is that?

A: That’s true. But that could happen at any time. Japan’s public debt load, as a ratio against gross domestic product, is bigger than that of the crisis-stricken Greece or Italy. Actually, there is no convincing explanation why Japan is not experiencing a financial panic at this moment.

Fiscal rehabilitation doesn’t mean that the government pays off all its debt. It means bringing government debt as share of GDP down to a certain level, to a level where debt no longer keeps growing indefinitely.

That’s completely true!

Note the conflation of monetary systems. The Eurozone crisis was entirely predictable and relates to the fact that the member-states are always at risk of insolvency because they do not issue their own currency. The propensity to a debt crisis in the Eurozone is intrinsic to the flawed design of their monetary system.

The Japanese government is always solvent and bond markets are not required to fund its spending even though the government choose to impose regulations on itself where it matches Yen-for-Yen deficits with bond-issuance.

That distinction is the “convincing explanation”. Everyone knows that they will get paid by the Japanese government and so the debt becomes a totally safe haven. Increasingly, investors know that they are at extreme risk of “haircuts” if not outright default when they purchase Eurozone debt.

Even the German bond tender “failed” this week. According to the latest Bundesbank report (April 11, 2012) – Federal bond issue – Auction result data, we learn that Germany’s central bank is doing exactly what it claims is the ECB and other central banks should not do – buy up national government debt in big quantities.

The Issue Volume was 5 billion euros and the Bundesbank purchased 1.13 billion euros worth – you can work out the percentage – just under a quarter. But moreover, the competitive bids were valued at 1.852 billion euros (that is, less than 37 per cent of the Issue Volume). In other words, the private markets are now reluctant to buy even German government debt.

I will write about the bond tender next week – it is highly illustrative of the hypocrisy that is crippling the Eurozone at present.

It also illustrates how central banks can intervene whenever they like to manipulate bond yields whenever they choose.

The interview with Dr Kobayashi then went into his elaborate plans of creating a “public-private fund to buy huge amounts of foreign assets (foreign-currency-denominated assets)” with trade surpluses to provide the Japanese government with funds to allow it to function when the government debt markets collapsed.

It is outer-space sort of stuff although I am sure those better versed in astronomy than me will tell us that their is at least science governing our understanding of outer-space.

There is no coherency in Dr Kobayashi’s plan.

Here is a sequence of graphs that the conservative media will not usually want to highlight and address the issues that concern Dr Kobayashi. They are all constructed using annual data available from the IMF World Economic Outlook database – the latest available being September 2011, which means the figure for 2011 is an estimate. More recent data from the Bank of Japan suggests the graphs are not inaccurate.

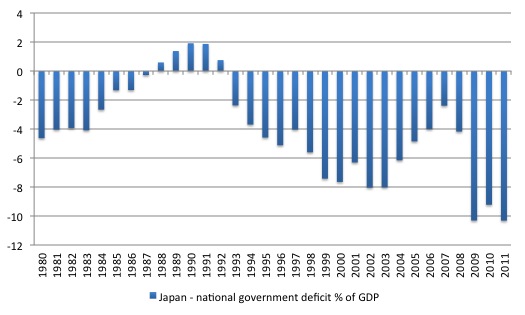

The first shows the evolution of the national government budget deficit since 1980 as a percentage of GDP with the business cycles clearly etched. If you were to consider the trend over this period you might conclude the deficits are getting bigger as a percentage of GDP although that would not be a reasonable way to proceed because the data does not cover (from start to finish) completed business cycles.

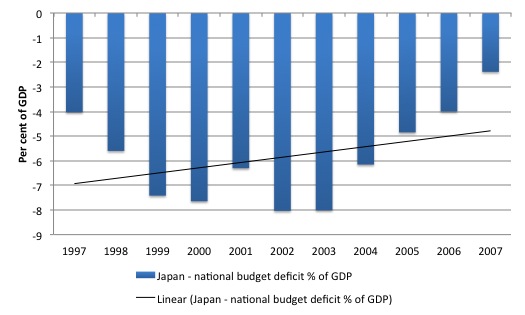

The following graph shows the same data (a subset of the last graph) over the last business cycle – more or less 1997-2007 (peak to peak) – and so includes one downturn and recovery. The black line is the simple linear trend over this complete business cycle and would suggest that the trend was negative. The budget deficits as a percentage of GDP were getting smaller once the economy had resumed growth after the debilitating and deliberately induced recession in 1997-98.

Recall, that the Japanese economy had resumed growth after the major property market collapse in the early 1990s and characters of Dr. Kobayashi’s ilk were predicting fiscal collapse then and pressured the government to raise taxes in 1997. The economy tanked badly as a consequence and the deficits grew again as a result of the collapse in tax revenue – that is, the automatic stabilisers drove the fiscal outcome in spite of the attempt by the Japanese government to reduce the deficit.

Once growth was re-established with the support of a sustained fiscal stimulus the deficit to GDP ratio began to fall again – quite significantly – in the period leading up to the current crisis.

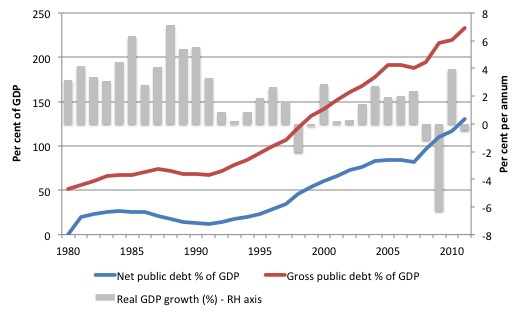

The next graph introduces the national debt statistics. It shows the evolution of gross debt and net debt as a percentage of GDP (left axis) since 1980 and on the right-axis (grey bars) the annual real GDP growth rate is plotted to provide cyclical information.

The IMF say that:

Net debt is calculated as gross debt minus financial assets corresponding to debt instruments. These financial assets are: monetary gold and SDRs, currency and deposits, debt securities, loans, insurance, pension, and standardized guarantee schemes, and other accounts receivable.

Gross debt consists of all liabilities that require payment or payments of interest and/or principal by the debtor to the creditor at a date or dates in the future. This includes debt liabilities in the form of SDRs, currency and deposits, debt securities, loans, insurance, pensions and standardized guarantee schemes, and other accounts payable.

The distinction is interesting for accounting purposes but, the currency-issuing Japanese government can always repay its gross debt irrespective of the other financial assets the central bank or finance department (treasury) might hold.

Would it be reasonable to conclude that debt was “exploding” around 2002 (when Dr. Kobayashi wrote the paper referred to in the introduction)? Answer: definitely not reasonable.

The behaviour of the public debt ratios is clearly cycle and certainly not exponential. Just the use of terminology such as “exploding” is tainted and reveals an ideological bias in the commentary. The mathematical properties of the time series are fairly clear – there is no “exploding tendency”.

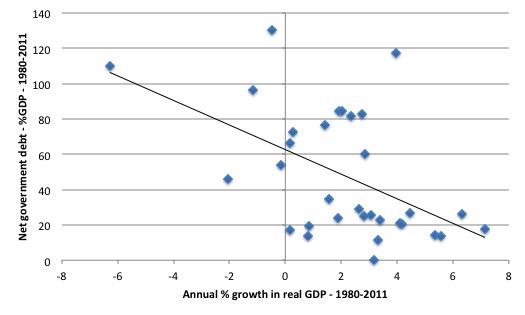

Finally, I plotted the annual real GDP growth rate on the horizontal axis of the next graph against the net national debt as a per cent of GDP on the vertical axis. The black line is the simple linear regression trend line, which suggests that when growth is strong the national net debt ratio declines and vice versa.

That is exactly what we would expect and why it is imperative to concentrate on growth rather than directly trying to reduce the financial ratios. We know from bitter experience that when the target of the policy becomes the financial ratios, real economic growth typically suffers and the financial ratios move in the opposite direction to the aim.

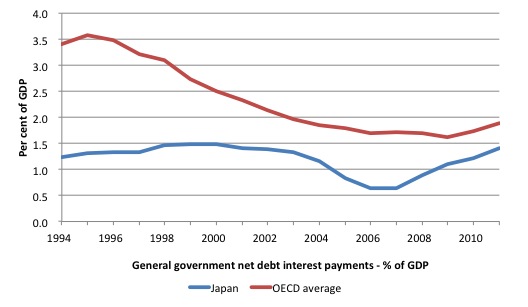

Consider the following graph which uses OECD data for the General government net debt interest payments as a percentage of nominal GDP. It shows the evolution of this data series for Japan and the OECD Total from 1994 to 2011.

Anyone spot any explosions? Any impending apocalypses? Any signs of snowballs gathering mass and causing trouble? Anything I have missed other than the clear cyclical behaviour (see previous graphs)?

Conclusion

Dr. Kobayashi is like all these mainstreamers – cracked records. They have been saying the same thing for two decades or more. The evidence keeps rejecting their predictions yet that doesn’t silence them.

Disaster is just about to happen – people are just about to do something – currency-issuing governments are just about to run out of money.

We all know about the story of The Boy Who Cried Wolf. Fortunately, for Dr. Kobayashi there is no wolf in this context!

Friday music suggestion

In the spirit of today’s theme – here is a classic from the 1970 Led Zeppelin Royal Albert Hall concert – 20 minutes or so of How Many More Times.

We might ask all these mainstream economists the same question – when do they plan to give up catastrophising (I know that is not a word?).

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back in the morning (Saturday for those who live around near me) – probably about as hard or easy as usual. No-one will get 6 out of 6 this week!

That is enough for today!

“(a word I read in a book by an Irish author I have just finished – In the Woods by Tana French – recommended)”

Was it preceded by ‘Do Bears’?

Bill

Did you have hair like Jimmy Page back in 1971 ?

Have a good weekend

Bill,

I understand the term was applied to the late Barry White after a poor performance in Oz! Just to keep the music references going.

Bill,

I wonder if the Japanese are accumulating savings partly or entirely due to demographics. If so, and the retirees at some point are spending the money (which of course the government can supply) might that lead to inflation, if the productive capacity of the country cannot supply all the goods/services the retirees want? (I think this is why there is so much work on robotics in Japan).

Dear Bill,

Is the graph on Japanese gross and net debt upside down? Net should be lower than gross.

Apart from that, i think that a detailed MMT-based analysis of Japan in the form of research paper(s) is missing. The closest substitute is Richard Koo’s analysis and books (which are of high quality).

If one takes a closer look on some statistics on Japanese economy the results are a bit worrying. Japanese civilian labor force is in decline since 2000 and the working age population on a plateau since 2005. Retail trade has also been on a plateau since 2000 and real compensation has been lagging productivity increases since Japan’s balance sheet recession started around 1990. (data are available in St. Louis Fed data browser).

It looks like Japan has an aging and declining work force with stagnant domestic demand, minimum energy resources and a strong competition from the BRICS. It faces strong challenges in actual real terms.

Your thoughts on the matter (maybe on a separate blog post) would be very interesting.

In “Beyond Our Means”, Wall Street Journal economics editor Alfred Malabre tells us not that we are heading over a fiscal cliff, but that we have already gone over it. We are heading irretrievably downward, feeling the rush of free flight, not yet sensing the sudden crushing stop that awaits us.

The book was released in 1987. Apparently it’s a really high cliff.

P.S. From Amazon, $1.49 new, $.01 used. (Full disclosure: I got mine free. I found it in a pile of junk.)

Hi Bill

I am still thinking about your above thesis but four things come to mind.

Did you consider possible changes in trade balances in your study and could there be an influence of a countrie’s ability to act as you prescribe if that aspect might change?

People in general are looking for securing some future safety when investing. Did you consider, that people may find other or better alternatives for investing their funds when confronted with e.g. depreciating currency or other financial repressive measures?

What would happen, if for unforeseeable reasons, the yen suddenly looses considerable value and as a result, the rate of inflation grows suddenly?

Did you consider demographical aspects?

Dear Kostas Kalevras (at 2012/04/14 at 2:55)

You asked:

Yes, my mistake. I have replaced the graph. I was rushing (as usual).

Thanks very much for the editorial help.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

I am surprised that you have never heard the phrase “They know shite”. It has a very useful extension, the phrase “They are ‘gobshites’.” where gob is the irish gaelic for mouth, and when such people open their mouths …….. However, be careful. It is such a useful word that it is likely to be ‘le mot juste’ in so many situations where it may not be appropriate.

Dear A R Manning (2012/04/16 at 4:36)

I had heard of the word (and phrase) before but it is not commonly used in Australia. But I was reminded of how effective it is when I was reading In the Woods, which, of-course is set in Ireland.

best wishes

bill

From an obscure speech given by Harry Truman on September 11, 1951 at the dedication of the GAO office building:

“Now, I would like to say a word to comfort and console those who fear that we are spending our way into national bankruptcy. This alarming thought has some currency in certain circles, and it is used to frighten voters–particularly as visions of elections dance through the heads of gentlemen who are politically inclined.

“I want to say to these gentlemen who are spreading this story, ‘Don’t be afraid–don’t be afraid.’ This is something that has been worrying you for a number of years now. It’s something you’ve been saying over and over again. It wasn’t true when you began to say it, it has not been true as you have repeated it over and over ever since, and it’s further from the truth than it ever was.”

http://crooksandliars.com/karoli/harry-truman-has-some-advice-paul-ryan

Hi Bill,

ALthough currency-issuing governments aren’t going to default on their debts (unless they choose to), do you think that certain countries (such as the US) with very large and growing trade deficits might eventually face a harsh balance of payments crisis?

It seems to me that the longer these large trade deficits are allowed to grow, the worse the potential for a serious currency crisis becomes, especially as deficit countries become increasingly dependent on imports. Not addressing this potential problem whilst pursuing gargantuan compensatory budget deficits might be a bit like putting a sticking plaster over a badly infected wound.

This deficit-spending approach might be fine if the inherent rebalancing mechanism of floating currency exchange rates was allowed to operate, but at present this is being subverted by currency manipulating countries such as China.

I just read Godley’s paper “seven unsustainable processes” where he points to this as the greatest potential future threat to the US economy. Nowhere does he mention that the US might default on its debts – why should it? But he makes the case that this might not even be relevant in the case of a sudden and dramatic fall in the value of the dollar. What do you think?