I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

OECD – all smoke and mirrors

I am taking a brief rest from the Eurozone crisis – which will probably blow up again in the coming weeks as the Spanish austerity drives the bond markets in the opposite direction than was intended by the Troika – and the latter call for even harsher cuts to unemployment benefits at the same time as their austerity policies force unemployment to continue its inexorable rise upwards. Today, I have been reading the latest OECD Report (April 12, 2012) which is attracting attention – Fiscal Consolidation: How much, how fast and by what means?, which is part of their Economic Outlook series. It is really a disgraceful piece of work but will give succour to those politicians who are intent of vandalising their economies and making the disadvantaged pay more and more for the folly of the elites. It is an amazing situation at present. I am also reading a book – Pity the Billionaire – which I will review in the coming week. It examines how it is that the the popular response to the crisis which was caused by an excess of “free markets” is to attack government regulation and intervention and demand even freer markets. The OECD are part of the battery of institutions that fuel this crazy right-wing conservative response (the “unlikely comeback” in Pity the Billionaire terms) to the crisis through their highly tainted publications.

The OECD is still trying to pretend it has something to offer the public debate. Like the IMF, the OECD has moved well beyond its original charter (which was as a progressive force on the World stage), and is now a major part of the problem.

Their latest report is 5.9 mbs of nonsense.

Normally astute UK Guardian journalist – Larry Elliot – wrote (April 12, 2012) that the – OECD report will please George Osborne. The article went like this:

If you want to understand why George Osborne is so keen on austerity, you could do worse than dip into a report released on Thursday by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which details how much pain countries in the rich west are going to have to endure in order to knock their public finances into shape. Plenty, is the short answer … Osborne will like this study, since it provides intellectual cover for his deficit-reduction programme.

Larry Elliot provides three qualifications to the OECD analysis, which I will discuss in more detail soon:

1. Debt levels are not historically high in many nations – they were much higher at the end of the Second World War.

2. The 50 per cent debt ceiling set by the OECD as being prudent is “a bit arbitrary”.

3. “it may be that we are getting things back to front” because “low growth leads to high debt levels, rather than high debt levels leading to lower growth”.

But then, in closing he gives the game away by saying that:

Osborne is right to be worried about debt … This, though, is not really about ends but about means – how much austerity the economy can bear before it kills off the growth that has to be a big component of any deficit reduction plan, and the right mix between fiscal and monetary policy. At present, monetary policy is doing all the heavy lifting, but quantitative easing contains risks of its own, not least the serious repercussions if financial markets suspected for a moment that central banks were secretly seeking to “monetise” (inflate away) the debt.

At which point we are back into a neo-liberal framework which has very little predictive capacity. The central banks could quantitatively ease all the outstanding public debt if they chose at present and there would be no inflation.

And if banks did suddenly find enough credit-worthy customers and dramatically increased their loans, and those customers suddenly withdrew all the credit created and spent up big on goods and services then we would observe three things immediately: (a) real GDP growth would rise – in the World and in the nation undergoing to credit expansion; (b) employment would rise and unemployment would fall; and (c) budget deficits would decline (and public debt issuance under current arrangements would decline).

It would be highly unlikely that inflation would be a concern given the amount of spare capacity that is around at present.

The overall problem I have with articles such as that above is that they are totally uncritical of the initial premises. He takes as given (other than saying things are a “bit arbitrary”) the key propositions that the OECD base its conclusions on. Closer examination shows that the analysis is more than a bit arbitrary. On key propositions it is totally unreliable and should not be used as the basis of policy analysis.

Just using OECD-style terminology – such as “how much pain countries in the rich west are going to have to endure in order to knock their public finances into shape” – is loaded

Upon what basis does one conclude that the rich western nations have public finances that are out of shape? What is the benchmark? Do we conclude that because there has been a serious collapse in real GDP growth in recent years and tax revenue has shrunk that the cyclical impact of the budget outcome means the latter is “out of shape”?

The more reasonable conclusion – once we fully appreciate what a budget outcome actually is and what role fiscal policy plays in an economy – is that the real economy is out of shape and that our efforts should be focused on restoring growth and reducing unemployment. The budget outcome reflects the malaise but isn’t the cause of the malaise.

The OECD and IMF and the rest of these out-of-date organisations have created the perception that the budget outcome is the problem and so policy has to be focused on “fixing” that problem. In doing so, they are making the actual problem worse.

The budget outcome is, in fact, a rather irrelevant accounting number and should never be the focus of policy.

Take for example the question of debt limits – which Larry Elliot described as being a bit arbitray. This is what the OECD said in their “Key Policy Messages” in the latest publication:

Many countries face enormous fiscal consolidation challenges. Even if debt-to-GDP ratios stabilise over the medium-term, they would remain at dangerous levels.

Countries should reduce debt levels to around 50 per cent of GDP or lower to provide a safety margin against future adverse shocks.

Dangerous in relation to what? We have a nation that for many years has had public finance parameters well beyond these limits – the second largest economy in the World (Japan). So what danger has it faced?

Solvency? – it issues its own currency and can do that whenever it wants to meet any yen-based obligations.

Interest Rates? – it has maintained near zero short- and long-term rates for two decades.

Inflation? – it fights against deflation.

More recently, only the Eurozone nations which clearly face insolvency risk because they do not issue their own currency have seen any upward movement in bond yields as their deficits have risen. That is entirely predictable given the flawed monetary system. In the US, for example, we have not observed that at all.

The Report nor the supporting papers used as authority also fail to establish that nations are in “danger” if they fail to reduce their deficits.

In the main body of the text the OECD say:

A natural question is then what reduction in debt would be warranted. While different debt targets will be appropriate for different countries, a target of around 50 per cent of GDP can nonetheless be supported by some arguments. For example, empirical estimates suggest that the performance of the economy weakens in various respects around debt levels of 70%-80% of GDP: interest rate effects of debt seem to be more pronounced (Égert, 2010), offsetting saving responses to discretionary policy changes become more powerful (Rohn, 2010), and trend growth seems to suffer …. Building in a safety margin to avoide exceeding the 70%-80% levels in a downturn suggests aiming at a target of 50 per cent or even lower during normal times.

The two papers cited above are – Égert, B. (2010) ‘Fiscal Policy Reaction to the Cycle in the OECD: Pro- or Counter-cyclical?’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 763 (access) and Röhn, O. (2010) ‘New Evidence on the Private Saving Offset and Ricardian Equivalence’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 762 (access).

The relevant sections that the latest OECD Report referred to above calls upon in the Égert paper are paragraphs 49 to 53. In relation to debt thresholds we read:

50. A similar non-linear effect is detected for public debt … For public debt levels above 89% to GDP, fiscal policy is pro-cyclical. At intermediate levels of between 30% and 89%, the fiscal policy reaction is either neutral or mildly pro-cyclical and becomes counter-cyclical below 30%. This result can however be obtained only if the cycle is captured by the output gap as no non-linear effects can be established, if the cycle is measured by GDP growth …

52. Panel threshold models were used to analyse a possible non-linear relationship between public debt and the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates in OECD countries. While it is difficult to establish strong non-linear effects for all OECD countries for 1995 to 2010, long-term interest rates appear to be a non-linear function of public debt for the G-7 countries (excluding Japan) in recent years (2007:q1-2009:q4). The estimation results indicate a 4 basis point increase in long-term rates relative to short-term rates if public debt exceeds 76% of GDP. The effect of public debt on long-term interest rates is not statistically significant below this threshold.

We thus learn that the key result is highly sensitive to specification and variable construction. The basic result can only be obtained if they use their output gap measure. This variable, in turn, is generated from other modelling and is based on flawed notions of the NAIRU (which in turn is based on highly constrained specifications with particular “long-run neutrality” properties asserted).

In this regard, the author probably uses what we term to be a “generated regressor” (for the output gap) and unless that is accounted for bias is likely in the results (bias means in this context that the point estimates will be reliable estimates of the true mean. For those that are interested in this sort of issue read the original article – Murphy and Topel (1985) ‘Estimation and Inference in Two Step Econometric Models’, JBES, 1985, pp 370-379. There is nothing in the paper to explain how the author handled this issue.

When the more obvious and more precisely measured – real GDP growth variable – to reflect the swings in growth, their non-linear results disappear.

Further, “it is difficult to establish strong non-linear effects for all OECD countries”. But when the author does squeeze out something that suits the ideological bias of the framework used (and the OECD in general) all they can come up with is that the spread between long-term and short-term interest rates rise by 4 basis points when public debt exceeds 76 per cent of GDP.

Need I remind you that a basis point is equal to 1/100th of 1 per cent.

That is a frightening hike in long-term interest rates that the OECD has discovered – even if we take their highly contentious econometric modelling as reasonable.

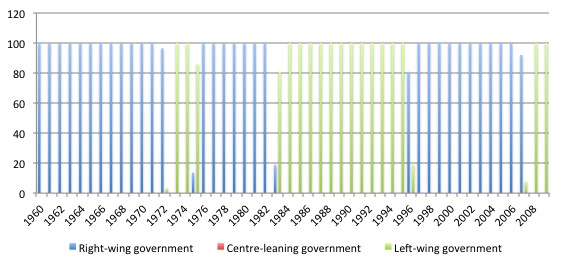

The paper uses the Comparative Political Data Set compiled by the Department of Political Science at the University of Bern. Among the variables the author uses, there are “Three types of political economy variables are added as controls: a) the strength of the government, b) the background of the head of government and c) the timing of general elections … The first variable measures the strength of the left-wing government and the second variable measures the strength of the right-wing government”.

I have seen this dataset used before and each time I shake my head wondering how it distorts the econometric results derived. Here is what that variable (in raw form) says about Australia from 1960 to 2009. Australian readers will join with me in laughter.

The variable in the Bern dataset prorates 100 per cent for each year across the style of government in power. So if the same party is in power an entire year their “style” gets 100 per cent. The left-hand axis is thus in percentage terms.

Apparently, Australia has either right-wing conservative government (blue bars) or left-wing governments (green bars) and nothing in between. Apparently, Australia is now being governed by a left-wing government – hence the laughter.

This variable is meant to be picking up the economic approach to Government with the naive underlying view that right-wing governments are more likely to engage in “fiscal discipline” relative to left-wing governments. The term “discipline” is, of-course, loaded.

There is no way that any reasonable commentator would call the present Australian government left-wing. It is firmly right of centre and has moved more to the right in recent years.

Take the following snapshot of policies:

1. It imprisons refugees from who land on our coastline having escaped desperate circumstances (some of which our own military has created – Iraq, Afghanistan).

2. It continues to fund elite schools and ensure that public schools are starved for funds. When confronted with a recent report (the Gonski Report) which demonstrated that our public school system is falling dramatically behind world standards (literacy, numeracy etc) and need $A5 billion injected immediately, the Government responded saying its priority was to achieve a budget surplus.

3. It refuses to increase the unemployment benefit which is now well below acceptable measures of the poverty line even though their own budget forecasts predict their policies will increase unemployment.

4. It continues to “occupy” indigenous communities with its punitive “intervention” policy.

5. It is obsessed with achieving a budget surplus even though it is killing economic growth. It says it has to do this to placate the financial markets and preserve its credit rating.

None of these policies, which are centrepieces of the current government approach are remotely “left-wing”. They all define what is reasonably called a “right-wing” approach.

Further, the key econometric results appear to be highly sensitive to specification (the model design) and the data used to represent the variables (the so-called transformations).

For example, the author admits that:

… the results for the quarterly fiscal policy reaction functions show that whether or not fiscal policy is pro-cyclical depends crucially on how the business cycle is measured: different measures can result in contradictory results for a country using the same specification and estimation method. Third, some of the controls (e.g. the political economy variable) are available only at annual frequency, which decreases the degrees of freedom rapidly for a data set that typically spans over 20 years …

The general point is that the key results are not robust across specifications and transformations.

In the Röhn paper, we learn that:

… there was considerable heterogeneity in the results … [of the preliminary unit root tests which are crucial to model specification] … Despite some of the tests being inconclusive, one cannot exclude the possibility that there exists a co-integrating relationship between the I(1) variables … the insignificance of the error correction term points to possible misspecifications in some of the countries …

So like all these OECD studies there is a lot of manipulation of the data and econometric specifications to get the results that finally appear. I also would note that the datasets combine economies with quite different monetary systems and exchange rate setting modes which are not recognised nor controlled for. That alone renders much of this sort of panel-set modelling difficult to interpret.

For example, it is clear that at present the dynamics with respect to the interaction of government and, say, bond markets is quite different in the Eurozone nations than elsewhere. In many cases, the Eurozone deficits are lower (as a percent of GDP) than is the case in other nations.

Further, when you dig a little deeper (for example, footnote 9) you read that endogeneity is a problem. We read that the:

The MG estimator does not explicitly control for endogeneity issues. Therefore also IV estimators were used (difference and system GMM). These estimators, however, are generally designed for large N small T panels, which does not apply to the sample used. In addition these estimators rely on a homogeneous panel. As an intermediate approach we also applied the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator, where long-run coefficients are restricted to be homogeneous whereas short-run parameters are unrestricted. While in all cases the parameter estimates of the fiscal variables were in general comparable, estimates for the controls varied considerably.

So we cannot be sure what variable is driving the show. The model assumes that the right-hand variables are independent of each other and explanatory of the left-hand variable – private saving as a percent of GDP.

There is no formal analysis of the likely interdependence between the government deficit and real GDP growth for example (in the short-run model). I could go on.

I am well-trained in these techniques and issues. The modelling and results presented did not leave me confident that the results would stand up to scrutiny. It is very likely that I could get very different results by more formally modelling the systems-nature of the data (for example).

But even if we suspend our disbelief somewhat the author finds that:

… all else equal a fiscal stimulus of for example 5% would lead to an immediate increase in private saving of 2% … This may limit the ability of discretionary fiscal policy even more as an indirect offset may occur to the extent that government actions put upward pressure on bond rates and thus borrowing costs.

Note the “may limit” terminology. The modelling does not examine the link between fiscal deficits and interest rates. The suggestion in this conclusion is pure assertion and reflects the ideological bias of the author and the framework used. How does the author explain Japan, the US – for example. Relatively high budget deficits and zero interest rates and no suggestion that interest rates will rise. In Japan’s case, long-term interest rates have been around 1 per cent for two decades. How do they explain that?

But the first finding (in the quote above) is entirely what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) would suggest (in direction). The private saving is the ratio to GDP. The authors find strong evidence that a fiscal stimulus stimulates real GDP growth (in their dynamic model component) and that real GDP growth stimulates the private saving ratio.

A central plank of the attack that Keynes led on the mainstream approach of his day was that the latter was compromised by its propensity to enge in compositional fallacy. While these type of logical errors pervade mainstream macroeconomic thinking, there are two famous fallacies of composition in macroeconomics: (a) the paradox of thrift; and (b) the wage cutting solution to unemployment.

In first semester of a credible macroeconomics course, students learn about the paradox of thrift – where individual virtue can be public vice. So when consumers en masse try to save more and nothing else replaces the spending loss, everyone suffers because national income falls (as production levels react to the lower spending) and unemployment rises.

The paradox of thrift tells us that what applies at a micro level (ability to increase saving if one is disciplined enough) does not apply at the macro level (if everyone saves aggregate demand and, hence, output and income falls without government intervention).

So if an individual tried to increase his/her individual saving (and saving ratio) they would probably succeed if they were disciplined enough. But if all individuals tried to do this en masse, and nothing else replaces the spending loss, then everyone suffers because national income falls (as production levels react to the lower spending) and unemployment rises. The impact of lost consumption on aggregate demand (spending) would be such that the economy would plunge into a recession.

As a result, incomes would fall and individuals would be thwarted in their attempts to increase their savings in total (because saving was a function of income). So what works for one will not work for all. This was overlooked by the mainstream.

The causality reflects the basic understanding that output and income are functions of aggregate spending (demand) and adjustments in the latter will drive changes in the former. It is even possible that total savings will decline in absolute terms when individuals all try to save more because the income adjustments are so harsh.

Keynes and others considered fallacies of composition such as the paradox of thrift to provide a prima facie case for considering the study of macroeconomics as a separate discipline. Up until then, the neo-classical (the modern mainstream) had ignored the particular characteristics of the macro economy that require it to be studies separately.

They assumed you could just add up the microeconomic relations (individual consumers add to market segment add to industry add to economy). So the representative firm or consumer or industry exhibited the same behaviour and faced the same constraints as the individual sub-units. But Keynes and others showed that the mainstream had no aggregate theory because they could not resolve the fallacy of composition.

So they just assumed that what held for an individual would hold for all individuals. This led the mainstream opponents to expose the most important error of the mainstream reasoning – their attempts to move from specific to general failed as a result of the different constraints that the macroeconomic level of analysis invoked.

In the context of today’s discussion, it is thus entirely reasonable that there is a private saving offset to fiscal stimulus.

The OECD paper by Röhn thinks this means that

… forward looking agents may anticipate that given a constant government spending path, current increases in budget deficits will have to be financed through higher taxes in the future (Ricardian equivalence).

So the author concludes that that “(o)verall the results provide evidence against a strict version of the Ricardian equivalence hypothesis in the long term”.

However, there is nothing in the analysis that models the behaviour of the saving ratio (that is, the motivation). The study is at the aggregate level and nothing can be deduced as to why private saving as a percentage of GDP has risen when there is growth or higher deficits (the two effects not capable of being disentangled in the modelling framework used).

The other point is that the saving offset in no way reduces the “effectiveness” of fiscal stimulus. It just means that to drive the economy to full employment, the structural budget balance has to be larger the higher is the private saving offset. The OECD want us to believe that higher deficits are “dangerous” although they don’t articulate exactly why.

It is all smoke and mirrors sort of stuff – the occasional veiled reference to “financial markets losing confidence” and the like.

There is nothing in any of the work cited that convincingly shows that a public debt ratio of 50 per cent is optimal or even desirable.

There is nothing in the OECD work that explains why Japan continues to issue debt at low yields and every time it expands its deficit in a discretionary manner the economy grows.

There is nothing in the OECD work that documents why fiat-currency issuing nations will encounter “dangerous” waters if they don’t cut their deficits in the short-run. It is all smoke and mirrors inference. Ideology rather than logic or fact.

Conclusion

I could provide more detailed analysis of the OECD Report and the supporting econometric studies that they draw upon for authority but I have run out of time. I have to catch a flight.

The overall conclusion is that the OECD is part of the problem not part of the solution. The sooner the national government withdraw their funding from institutions such as this the better we will all be.

That is enough for today!

Hi Bill

You state:

It examines how it is that the the popular response to the crisis which was caused by an excess of “free markets” is to attack government regulation and intervention and demand even freer markets.

I have strong doubts that we operated in a environment of excessive “free markets” over the past 30 years. I do agree that when deregulation of the banking industry is considered an excess of “free markets”, the statement may have meaning BUT the activities of Central Banks was everything but an expression of the idea of “Free markets”. Their continuous interference in the market whenever a problem occurred is nothing but serious manipulation and due to the fact that operators in the financial sectors were made to believe that they did not face any risk that would not be countered by Central Banks’ action, led to the unsustainable growth of debt. In real “free markets” misallocation of capital is allowed to be cleared before a real rejuvenation of the economy starts. This is the real problem we presently face and Central Banks the world over simply increase their dosage of the same medication not realising that the end result will be that much more disastrous.

Brilliant post from Linus Huber on how a barter economy functions. Well Done.

Linus : Read Polanyi’s “The Great Transformation”. For centuries now, free marketers have been saying that the invisible hand will fix everything if we just have the courage to hold firm and do nothing. And that of course never happens because the consequences are so heinous. Eventually the next generation of free marketeers comes along, and of course they aren’t interested in the lessons of history because that last generation of free marketeers lost faith or were thrown out of power, which lets the new generation say “… if only they’d held the line and let the market work its magic everything would have been fine, … this time we need a “real” free market”. And so the cycle begins again.

Bill : I really enjoy those posts where you get into the nitty gritty of the “science” of mainstream economics. Keep up the good work. As they say, there are “lies, damn lies, and statistics”. And that’s speaking as someone who thinks that good econometric modelling can be genuinely useful.

Alan Dunn, I understand your (sarcastic) point would you care to explain how central banks would emerge in a free market – where everything is decentralised.

jms.grmwd, free markets are by no means perfect but they are a helluva lot better than the ‘solutions’ being imposed throughout Europe. Some of the greatest improvements in prosperity on this planet occurred during periods of minimal intervention. I am not saying it is always the case.

In any case, it is drawing a long bow to conclude that an extended period of artificially low interest rates (during high aggregate demand no less) courtesy, say, Greenspan et al, did not play a key role in this whole mess.

Anyway I agree with Bill that the IMF and OECD have got no idea how an economy really works. This website is helping me get a better handle on this every day.

Cheers!

I certainly agree that free markets require a strict frame for those that are able to create credit (banks) as otherwise their self-interest will prevail over common sense with regard to the sustainability of systemwide credit expansion. I am of the opinion that if Central Banks would have monitored the measures of M3/M4 and would have included those aspects in their policies, their monetary stance would probably have been tightened numerous times in the past 30 years even at times when no inflation seemed to be in sight as far as the eye could see.

The horror associated with a period of negative inflation (deflation) in the official rate of inflation (which additionally is questioned by many on the scene with regard to its correctness) is completely misplaced when the reason for a deflationary period is based on enormous increases in productivity.

Well, that is of course my personal opinion and all of you may criticise me, but until I see real good reasons to change my mind, I will stick to what I intuitively feel to be correct.

Esp Ghia

“Some of the greatest improvements in prosperity on this planet occurred during periods of minimal intervention. I am not saying it is always the case.”

A fairly general statement? I don’t think that Ha-Joon Chang would necessarily agree with you?

“. . . (during high aggregate demand no less) . . . ”

These are the % increases in real GDP per capita for the USA.

2000 3.00

2001 0.04

2002 0.82

2003 1.58

2004 2.53

2005 2.12

2006 1.69

2007 0.91

To me, they don’t reflect a period of ‘high’ aggregate demand?

Linus Huber

“The horror associated with a period of negative inflation (deflation) in the official rate of inflation (which additionally is questioned by many on the scene with regard to its correctness) is completely misplaced when the reason for a deflationary period is based on enormous increases in productivity.”

The horror is associated with an extended period of both falling money wages and prices due to a fall in aggregate demand {not just prices falling due to an increase in productivity}.

Yes, Postkey

The gains in productivity did result mainly in large profits in the financial sector and the average joe did not enjoy any of the benefits that occurred from it. I am looking at the past 30 years by the way, not simply the past 10 years.

It’s disappointing that Larry Elliot believes that Gideon Osborne has a deficit reduction strategy. He has as little interest in the so called deficit crisis as I have. The conservative government are focused entirely on creating a rentier society fit for the 19th century.

Esp Ghia : What’s this “free market solution” that would be better than what’s being imposed on Europe now. I thought that letting relative prices adjust through deflation WAS the free market solution, and that was precisely what austerity in the GIPSIs was supposed to do.

Postkey, Chang is a great economists. Period. But I don’t need Chang to teach me economic history: we all know that even the facts are disputed in many instances. Some claim the the rise of Japan was due to heavy interventionism immediately post WWII; others claim that it was not until the early 70s that the Japanese government really ramped up its role, etc.

It seem odd, Postkey, that you would quote per capita numbers – of course they look rather emaciated compared to real GDP (so as to avoid any confusion here it is for the whole Greenspan era, sourced from http://www.indexmundi.com/united_states/gdp_real_growth_rate.html)

1987 3.2

1988 4.11

1989 3.573

1990 1.876

1991 -0.233

1992 3.393

1993 2.852

1994 4.074

1995 2.514

1996 3.741

1997 4.457

1998 4.355

1999 4.826

2000 4.139

2001 1.079

2002 1.814

2003 2.541

2004 3.468

2005 3.07

2006 2.658

But perhaps more pertinent was GNE or spending. After all absorption tells you about demand pressures. Those figures are almost invariably higher during that entire period – though I guess you already knew that.

Nice try.

jms.grmwd, how does hiking taxes during a period economic decimation sound like the free market to you??? For example, I defy you to try and buy anything “cheaply” in Greece (save for fast food). I was (un)lucky enough to spend some time there (specifically in Athens) during the last European summer and was absolutely gob-smacked that the cost of living felt cheaper down-under.

There is no easy or relatively pain free solution to southern Europe. Austerity is sure as hell not the answer and it does not reflect free markets in the least. Any one can build a straw man and burn it down. That’s why economists try to misrepresent competing model’s. It happens to MMT all the time – don’t you be a part of it as well.

My view is that the monetary union should disappear altogether and individual agents should be able to transact VOLUNTARILY using anything they wish – Drachmas, USDs, fish. I don’t know as it depends on what they trust. At the end of the day what matters is that it is not foisted upon them by their political overlords. Specifically Greece should default and have another crack in a post-default world without these ridiculous regulations where you can’t sell a book after 6pm, or a coffee without a licence (that seems to take a year to get!). The cronies have to be cleared out. There is no easy way to do this.

It is despicable that there is 20% official unemployment and that taxes are beoing introduced/hiked left, right and centre. Maybe a revolution will take place. Dunno.

I get the feeling that most people here simply look at the past few years and neglect to recognise that the problem was created over maybe the past 30 years. Today we simply get the results of past erroneous judgements by Central Banks and Governments. Not today’s policies are at fault but those of many years ago whereas today we have no more easy solutions but only a choice between short term strong pain or pain eased by some pain killer that however will probably extend the period of pain.

Esp Ghia : Does raising taxes sound free market to me? No. But then what is considered free market or not has always been pretty mysterious to me. l don’t think there’s a useful distinction to be made. There’s just a set of arbitrary laws which presumably you consider to be the best for promoting the general prosperity. You call that set of laws “the free market”. I favour a different set of laws. Just as arbitrary. No more and no less free. Provided both sets of laws are submitted to democratic approval of course.

jms.grmwd, the reason it’s a mystery to you (and many perhaps many others) is that it is regulary misconstrued by mainstream commentators – for instance, crony/corporate capitalism is NOT free markets. Large banks behaving badly, knowing full well that they won’t be allowed to fail by coercive governments is not free market economics. There is nothing arbitrary (or centralised or coercively regulated) about the free market. I conclude that it would be better (though far from perfect) than some different approach based on the idea that humans, as sentient beings, respond to incentives. For instance, increase the returns to thuggery by banning private drug consumption, and thugs will respond by entering the drug trade and meeting demand. Give governments too much power and watch bureaucrats massively abuse it.

Don’t even get me started on democracy (though I admit I don’t know a better system – you need to make it difficult for pollies to have thir primary allegince to their party instead of the country).

Esp Ghia : Modern crony corporatism isn’t the free market but neither is any other arbitrary set of rules and regulations. The tradition of calling one particular set “the free market” is nothing but a marketing ploy.

Phrases of the kind “xxx capitalism is not free markets” make me weep. It’s just an echo of (Austrian?) utopian thinking where the solution is always the premise – more free markets – but the “solution” never works, but only because the markets are never “free” enough.

It reminds me of the relationship between miscellaneous Trot groups and “the revolution”.

“It seem odd, Postkey, that you would quote per capita numbers . . . ”

Duh!

Esp Ghia : On further thought, I can accept “there’s nothing arbitrary, centralized, or coercive about the free market” if you’re willing to repeal the entire body of corporate law, property & conveyancing law, inheritance law, contract law, constitutional law, and that portion of criminal law that relates to victimless crimes. Once you’ve done that, I’ll repeal all labour, tax, health & safety, and environmental law and we’ll have a non-arbitrary, non-coercive, non-centralized free market. Nothing but handshake deals between free individuals.

The purpose of laws intends to reward behaviour that is positive for society (ethical behaviour) and punish behaviour that hurts society at large. Especially the latest activities by Central Banks and Governments, however, move in the exact opposite of the spirit of this rule of law. This is called crony capitalism and can be rather easily recognised when one considers the real purpose of laws.

Law makers who simply serve some special interest and completely lost their legitimacy by avoiding to serve society at large are undermining the real rule of law and endangering the principles which the economic success of Western Society was built on.

Naturally, nothing can be perfect and there will always some degree of corruptive behaviour which goes along with power but the degree of these violations are no more simply exceptions to the rule but became the rule. Over time it will have to face the electorate and I wonder whether democracy will be allowed to correct this massive corruption or whether somehow an authoritarian outcome will prevail in that each new set of leaders will, after being elected, continue with these policies.

Elections in France and Greece will provide some clue of the future, I suppose.

You see, Linus, there’s a lot I’d agree with in your posts, but it’s all apple pie dreams because you have this big disconnect. If you believe in small government and freer markets, then your government will be less democratic and unable to resist the potential corruption, because of the power of the rich to dominate those “free markets”. Which is what we observe every day.

@Esp Ghia:

“There is nothing arbitrary (or centralised or coercively regulated) about the free market”

It sounds to me like your definition of a free market is more about what it doesn’t have, and what a free market doesn’t have is government. Can you define free markets without mentioning governments? I don’t think so.

The problem I have with that is it draws a very distinct line between the public and private sphere, between state and corporation. What is the fundamental difference between a government and a company? They are both organisations comprised of people, they both have laws, leaders and hierarchies. Many companies even have small internal democracies (shareholder votes, board of directors).

Is it simply a matter of scale? Was the East India Trading company a state or a corporation? Walmart has over 2 million employees, four times the population of Luxemburg. It has it’s own laws, security force, and culture. Is it a state? It certainly has the power to disrupt economies wherever it goes. Is it part of the free market or a distortion upon it?

My point is, how can a free market remain so if large, state-like organisations naturally arise from it, which in turn dominate and distort it? What’s the difference in the end if a state creates a monopoly or a company does? If the key is to prevent this, how could it be called free if such structures are suppressed? Or is your argument that all large structures exist because of the state, and that without interference they are inherently unstable?

Grigory Graborenko, nice post. It should be obvious that the public and private sector usually have very different motivations and one only of those groups can sustain losses forever through the use of coercive power to extract income from the masses. So to answer your question, it is not a matter of scale.

Your points about how monopolies arise are much more interesting. I agree that natural barriers to entry may give rise to a monopoly – but I wonder how common that really is. In my experience monopolies usually arise as a result of artificial barriers, usually created by (sometimes well-intentioned) governments.

By the way, Wal-mart is a behemoth but does not possess coercive power in any true sense.

Cheers, and again, good post.

@ gastro george

@ Grigory Graberenko

You both gave me a good counter argument that makes me think somehow whereas I do believe that, in the long run, markets will take revenge on those that dare to try to change its nature and democracy, if it will not be suppressed, will rise against those that try to enslave us, once the suffering exceeds some unseen limit. At that point the real re-balancing act will be upon us, but, unfortunately, it will be no more apple pie at all.

What cannot go on forever, will not go on forever and because something did work for a long period of time, does not mean that it will continue to work for another long period time.

@Esp Ghia:

Do the public and private really have different motivations? Only in the last few centuries have a sizable number of governments been anything other than dictatorships. The motivation of the hereditary monarchies – what were they? To make a cushy life for themselves, their relatives and their close supporters. Also possibly to be remembered, to make an impact on the world. Or just simply for power. Even in modern democracies, these are the same reasons people seek election. How is that different from the motivation of a business founder? There are plenty of companies where the owners care more about their employees than many currently elected leaders.

Don’t forget that organisations don’t have motives – only the people within them do. People who inhabit private and public spheres are not different species, they are all still human. Don’t tell me that the two worlds attract different people – there are plenty who spend their lives moving between the two. The line is very blurry and is often crossed.

“By the way, Wal-mart is a behemoth but does not possess coercive power in any true sense”

They have extremely efficient supply chains that allow them to undercut almost anyone, and price them out of business. The small stores that go bankrupt as a result have no choice in the matter. How is that not coercive power?

“In my experience monopolies usually arise as a result of artificial barriers”

What was the state intervention that led to the railway monopolies in the early nineteenth century, USA?

Grigory Graborenko, again good points regarding power but they still face different constraints, and that impacts on their behaviour. But still I take your point on that matter. Regarding Walmart, outcompeting others is not coercive. Maybe you will argue Walmart is predatory but that would involve raising prices once competition disappeared – I am not sure that has been the experience. As for the railway monopolies in the US I confess I know little beyond a doco I saw (and only vaguely remember) where they were racing to reach the centre (from east and west). Perhaps these were an example of natural barriers that referred to. I was thinking more about regulated monopolies (remember Telecom – how do you think that evolved?)

Cheers.

@Esp Ghia:

I agree, public and private spheres are quite different in practice, on average. The place where we part ways is the insistence that there is a fundamental demarcation between the two. If a state can act like a corporation, and a corporation can act like a state, and every single instance of either is a mixture of both, then where does that leave free markets? Maybe you can’t even call it free markets, but something like free organisations, or free co-operation.

I mentioned Walmart because it’s a good example of a naturally arising monopoly. The more they grew, the faster they could grow. Monopolies are about market share, not prices. When a company controls so much of the market, it is not a level playing field. They can threaten suppliers with massive loss of business, and get disproportionate discounts no one else can, despite not really adding any value or efficiency to the actual product. Microsoft put Netscape out of business by offering their product for free – they could take the loss, Netscape couldn’t. There is a lot of power to be gained by being big, and a lot of the time it has nothing to do with the quality of the product – the only thing that should matter in a theoretical free market. Companies like that are more state-like than their competitors, more centralized.

I don’t think you can take the line that the private sector can ever be perfectly competitive and work entirely on principles of trade. If you start from the incredibly combatitive notion that labor is a good that workers are trying to get the best price for, and capitalists are in constant competition with them, you end up with a resentful workforce who hates the bosses and do as little work as possible. No business can succeed with such a nihilistic culture. The ones that last are the ones that have a good internal culture, where everyone feels like they are actually doing something meaningful, however small. Even a business is a mini-society. On the other end of the scale, hardly any government worker is truly altruistic – they need to get paid too!

So when you say that a society works best with a free market, my interpretation of that is “private sector good, public sector bad”. I think that misses the point. It might be more reasonable to suggest that more centralization leads to more abuse of power – whether public or private. It’s just that on average, states tend to be more centralized than companies. I think that’s why democracy works so well – it decentralizes power by spreading a little to everyone.

“whereas I do believe that”

Very difficult to argue against belief. If you believe something then feel free to continue doing that.

But simply believing it doesn’t make it real.

@ Neil

Great discoveries were made by a strong believe in one’s theory. So do not discard it that easily.

Power creates a counter weight to it over time. Income inequality can also not grow indefinitely. So let’s talk about it after maybe 3 years from now and we will see, whether my conviction has any resemblance to reality.

Nice posts Grigory. Without wanting to sound too much like apple pie myself, it’s also worth pointing out that “the free market” also implies a particular a particular form of social relationship – a financial one. But there are other models as well. I could cherry-pick Linux and OpenSSL as examples of advanced products produced by purely voluntary means, or the cooperative movement, etc.

This is what is annoying about the free market obsessives. While it’s true that markets CAN be the most efficient form of organisation (where there is low cost of entry, multiple suppliers, etc.) it’s in no way true that they ARE ALWAYS the solution, and in many areas they are entirely negative as a means of organisation. Context (and reality) is everything.

Editorial Note:

I urge all new commentators here who wish to add to the discussion to familiarise yourself with my Comments Policy. I delete many comments that violate this policy.

In general:

1. I will not publish comments which merely say that “everything governments do is unsustainable”. You are entitled to that religious viewpoint but the purpose of the discussion is to provide evidence and/or logic that interacts with the blog post and provides something interesting.

2. I will not act as a free advertising space for well-known deficit terrorists who continually rant about the dangers of public debt and deficits. I sometimes comment on such papers but only to develop concepts. Merely providing a link to non-academic paper that apparently shows that public debt is dangerous but pitches a marketing message for the consultant’s services is not going to cut it.

I am happy to host open discussion here but it has to be engaging with the posts.

best wishes

bill

Grigory Graborenko asked: “What was the state intervention that led to the railway monopolies in the early nineteenth century, USA?” Why, use of the “public domain” condemnation procedure to take land from its owners and give it to the various railway corporations. Which is why the privately owned railway that Dabney’s grandfather created in Atlas Shrugged is so laughable. It seems it could not be done without state intervention, and certainly never was done without state intervention. In Europe as well as America. And it was throughout the nineteenth century, not only in the early part. The railways, and the mine owners, had true means of coercion, too. Ever hear of The Pennsylvania Coal and Railway Police? Ever hear of The Pinkertons? We haven’t seen the like recently, but I think that’s not going to last long. Have you heard of Dyncorp? Xe? Raytheon?

@ Grigory Graborenko on 17th at 15:42

You hit the nail on the head in your last para. With your reference to Democracy.

It seems to me that the professional economists think of the economy and how it works or should work, too much in isolation of the reality in which a modern economy only exists embedded in a Political system. Be it a Democracy (which unfortunately is generally understood only to be possible as a Parliamentary Democracy with no inkling of “Direct” Democracy or lets say “Citizens Democracy”, models!) rather than the extremes of an absolute Dictatorship, in which potentially, a pure economic theory could probably be applied and tested no matter what. (although the examples before us do much worse, despite the illusion of some that they should have it easier.)

However what I want to bring to the open here is, that the economies within Parliamentary Democracies, not just by country, but collectively are failing together with all the others, because of the high degree of interdependence, and so together seriously endanger our lives in all the world.

Why? Because of wrong economic theories or because of the political System? It seems most obvious to me, it is because above all Parliamentary Democracy is failing! Why? Because the task far exceeds what we can expect from politicians to which the citizens with their 3, 4, 5 yearly or so vote and delegate their judgement responsibility to others, with no recourse or accountability because of the naïve expectation that that can effectively happen at the next election, after vested interest powers have obtained their donation and lobbying rewards to the detriment of the rest of the society. The integrity required from politicians and the party political systems themselves, are so idealistically high or impossible to fulfil, because members have to follow party discipline according to their selection committees and as dictated by party ideology and their supporting and financing vested interests. Furthermore such elections are really a farce, because the citizen with essentially one vote has to determine who will represent him best in a very complex

For now, world communism is off the tables. We capitalists are still intoxicated from endless victory parties and selfgratulation. The main game now is trying to stay in power and keep and keep the privileges and the money the so called investment specialists frittered away from the superannuation savings the working public had to invest in the investment funds the Banks and other “Investment specialists” were able to organise with taxation help from the governments. Then these “Specialists” largely gave themselves indecent Bonuses and benefits as much as possible with little tax into there own tax free bonuses and other tax beneficial mechanisms for the great genius they displayed in setting unmentionable sums in the “sand”, and leaving most of the saving public with great shortcomings and worries for their future and retirement. And what does the Government do? They increase the working age until retirement savings from these funds can be accessed by the rightful owners. Why did this happen? Because of economic theories or because of the political System? No doubt both and without drastic changes of both we can not have any hope to be saved!

Listening to the proceedings of the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET), founded by George Soros with $75 million , which have just ended in Berlin (April 12 – 15. “Paradigm Lost”, ineteconomics.org), I feel one should be encouraged with what the economic fraternity is undertaking in seeking change. Will any of the leaders of our so called “Democracies” find similar insight for drastic insight for the need to change and throw on a broad and loud public discussion and seeking together with the economic fraternity to find a worthwhile way to avoid catastrophe. Or do we have to hope that may be only out of chaos and revolution the human race will get a chance for a new beginning, or should we try anarchism?

re mine from the 19th,

sorry for not completing the third paragraph which should end with:

“………..should represent him best on a very complex menu on offer and very vaguely explained. The voter is expected to be a genius in contrast to those who offer themselves as leaders!”

@Fred:

I agree that parliamentary democracy is a strange and inefficient beast. I suspect it came about because at the time communication was only possible by horse or boat, which meant delegation to a few was the only possible way to run things effectively. Now with the internet, that is no longer an obstacle.

Still, the biggest hurdle to full democracy is our lack of trust in each other. Almost everyone I talked to about it seems to think they could be trusted with that kind of power but the “masses” would run amok. It’s that old thing paradox about more than 50% of people thinking they are above average. Divide and conquer.