In an early blog post - Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy (October 15, 2009)…

IMF struggling with facts that confront its ideology

I haven’t a lot of time today (travel) but I thought the latest offering of the IMF was interesting. In their latest World Economic Outlook (April 2012 – which will be released in full next week) they provided two advance chapters – one – Chapter 3 – Dealing with Household Debt – demonstrates just how schizoid this organisation has become. They are clearly realising that their economic model is deeply flawed and has failed to predict or explain what has been going on over the last five years. That tension has led to research which starts to get to the nub of the problem – in this case that large build-ups of debt in the private domestic sector (especially households) is unsustainable and leads to “significantly larger contractions in economic activity” when the bust comes. They also acknowledge that sustained fiscal support is required to allow the process of private deleveraging to occur in a growth environment. But then their ideological blinkers prevent them from seeing the obvious – that sustained fiscal deficits are typically required and that in fiat monetary systems this is entirely appropriate when . Which then leads to the next conclusion that they cannot bring themselves to make – the Eurozone is a deeply flawed monetary system that prevents such fiscal support and should not be considered an example of what happens in fiat monetary systems. Some progress though!

The features of a balance sheet recession are summarised as follows:

- The private sector builds up massive debt levels to buy property and speculative assets.

- The asset prices rise as demand rises but then eventually the bubble bursts and the private sector is left with declining wealth but huge debt.

- The private sector then start restructuring their balance sheets – and stop borrowing – no matter how low interest rates go.

- All effort is devoted to paying back debt (de-leveraging) and households increase their saving and reduced spending because they become pessimistic about the future.

- A credit crunch emerges – not because there is enough funds but because banks cannot find credit-worthy borrowers to lend to.

- Attempts at pumping liquidity into the banks will fail because they are not reserve-constrained. They are not lending because no-one worthy wants to borrow.

- The faltering spending causes the macroeconomy to melt.

- With this private contraction (reducing debt, saving) the only way out of the “balance sheet recession” is via sustained public sector deficit spending.

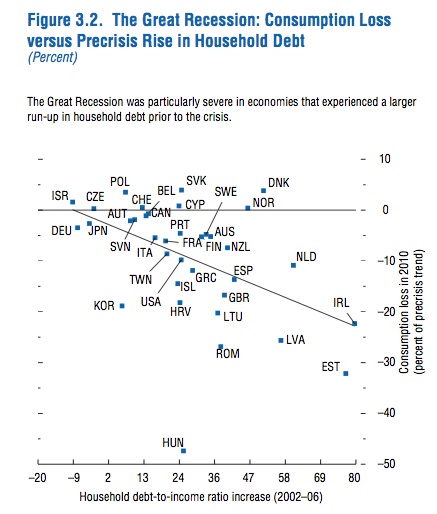

The IMF conduct some empirical analysis – of past housing market busts and the relationship between the rise in household debt and subsequent adjustments in private consumption.

They provide this graphic (their Figure 3.2) which plots the consumption loss in 2010 (vertical axis) against the rise in household debt from 2006 to 2010. They compute the consumption loss in 2010 as the “gap between the (log) level of real household consumption in 2010” and an “extrapolation of the (log) level of real household consumption based on a linear trend estimated from 1996 to 2004”.

Supported by some (simple) regression analysis the IMF finds that:

Housing busts preceded by larger run-ups in household leverage result in more contraction of general economic activity … household deleveraging tends to be more pronounced following busts preceded by a larger run-up in household debt … when households accumulate more debt during a boom, the subsequent bust features a more severe contraction in economic activity … downturns are more severe when they are preceded by larger increases in household debt.

The have some issues with their regression approach (for example, it is unclear whether they controlled for fiscal interventions) but in general these results are exactly what one would predict from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) starting point.

It is what we were saying in the 1990s as the debt buildup was gathering pace. The only inexactitude in our forecasts was exactly when the whole ship was going to start sinking. It was clear it would despite the narratives from the mainstream (which I canvassed in yesterday’s blog – The Academic Spring), that when the collapse came it would be big – the question in our minds (MMT developers) was not if but when.

The IMF also attempt to come to terms with distributional issues. They write:

A shock to the borrowing capacity of debtors with a high marginal propensity to consume that forces them to reduce their debt could then lead to a decline in aggregate activity.

They acknowledge that “household debt increased more at the lower ends of the income and wealth distribution during the 2000s in the United States” (and elsewhere) as real wages were being squeezed. See more on this later.

They recognise that debt becomes toxic not necessarily because the risk profile of the debt was poorly assessed in the first place. Rather that:

… a rise in unemployment reduces households’ ability to service their debt, implying a rise in household defaults, foreclosures, and creditors selling foreclosed properties at distressed, or fire-sale, prices.

Appropriate fiscal interventions that prevented unemployment from rising in 2008 would have significantly reduced the proportion of “toxic debt” being held by banks and more quickly resolved the bank solvency issue.

The IMF acknowledges that “debt overhang” – in firms and households – may reduce a firm’s access to “funds to finance profitable investment projects ” and/or lead to households foregoing “investments that improve the net present value of their homes”.

IMF policy implications

The IMF Report then considers “four broad policy approaches” that are “complementary” and would “allow government intervention to improve on a purely market-driven outcome”.

1. Temporary macroeconomic stimulus

Here we learn the obvious that when there is an “abrupt contraction in household consumption” aggregate demand losses can be reduced by “offsetting temporary macroeconomic policy stimulus”.

So the IMF is now categorically rejecting the Chicago-school line that fiscal policy has no real effects. Thje IMF say that fiscal policy is effective because the economy is “nonRicardian”.

The IMF Report concludes that:

In an economy with credit-constrained households, this provides a rationale for temporarily pursuing an expansionary fiscal policy, including through government spending targeted at financially constrained households.

As clear as it could be. Government fiscal expansion is good for an economy where private spending growth lapses. Note this is a different point to whether fiscal deficits should be sustained indefinitely.

That is, there is a distinction between the level of on-going fiscal support in overall aggregate demand – calibrated at full employment and the change in the fiscal stance to accommodate rapid changes in other expenditure components.

But at this point, the underlying ideological-bias of the IMF enters the fray. They say:

Macroeconomic stimulus, however, has its limits. High government debt may constrain the available fiscal room for a deficit-financed transfer, and the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates can prevent real interest rates from adjusting enough to allow creditor households to pick up the economic slack caused by lower consumption by borrowers.

Which is a statement void of meaning. The limits to macroeconomic stimulus for a fiat-currency issuing government are the real resources that are available for purchase in the currency that the government issues.

Such a government can always purchase whatever is for sale in its own currency, although that doesn’t mean that it should. At the very least, in a recession, the government can always offer a job to labour that is not in demand from other employers. There is no financial limit to that capacity.

The “fiscal room” is always real (what can be bought) and never financial.

For a currency-issuing government, the level of debt is not a constraint on its ability to spend. Such governments might impose arbitrary budget constraints on themselves but they are not intrinsic to the features of the monetary system.

Further, even within those voluntary constraints, which usually involve the government forcing itself to match its deficits with private debt issuance, the government retains the capacity to influence the yields it pays on the debt issues. The central bank can always control yields at chosen maturities should it choose to do so.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

2. Automatic support to households through the social safety net

The IMF say that:

A social safety net can automatically provide targeted transfers to households with distressed balance sheets and a high marginal propensity to consume, without the need for additional policy deliberation. For example, unemployment insurance can support people’s ability to service their debt after becoming unemployed, thus reducing the risk of household deleveraging through default and the associated negative externalities.

Even better would be a Job Guarantee, which would constitute a high-quality automatic stabiliser and ensure there was always income support for those who could not find a job elsewhere.

Note that the IMF supports the notion of income support to avoid debt default and “associated negative externalities”. In a footnote, they also note that the “safety net needs to be in place before household debt becomes problematic” which also reinforces the notion that stabilisation schemes such as the Job Guarantee should not be seen as emergency measures.

Rather they should be part of the overall macroeconomic stability framework that is in place at all times. Activity within the Job Guarantee would then vary on a counter-cyclical basis as it should.

However, they then claim that for the automatic stabilisers “to operate fully requires fiscal room”, which is again a statement void of meaning.

Do they mean that the government cannot run a policy such as the Job Guarantee unless there is food available for the unemployed to eat. In which case I agree. But to suggest the government cannot afford to allow the automatic stabilisers to operate is nonsense.

3. Assistance to the financial sector

The IMF supports socialisation the losses of the financial sector via “recapitalizations and government purchases of distressed assets” to allow the banks to retain profitability. This is an interesting proposition coming from an institution that proposes market-based solutions when it comes to the welfare of the disadvantaged. It seems that corporate welfare is acceptable. Again, an ideological twist.

I agree that the government is responsible for maintaining financial stability in the monetary system. But that is a separate issue to allow gains to be privatised and losses to be socialised in a capitalist system where risk and return should go together.

In that context, a failed bank should be nationalised and corporate excesses eliminated so that depositers etc are protected and forced asset sales which would compound the balance sheet recession are avoided.

Further, in the blog – Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – I noted that the only useful thing a bank should do is to facilitate a payments system and provide loans to credit-worthy customers. Attention should always be focused on what is a reasonable credit risk. In that regard, the banks:

- should only be permitted to lend directly to borrowers. All loans should be in the currency of issue and should be shown and kept on their balance sheets. This would stop all third-party commission deals which might involve banks acting as “brokers” and on-selling loans or other financial assets for profit.

- should not be allowed to accept any financial asset as collateral to support loans. The collateral should be the estimated value of the income stream on the asset for which the loan is being advanced. This will force banks to appraise the credit risk more fully.

- should be prevented from having “off-balance sheet” assets, such as finance company arms which can evade regulation.

- should never be allowed to trade in credit default insurance. This is related to whom should price risk.

- should be restricted to the facilitation of loans and not engage in any other commercial activity.

It is true that the meagre separation of banks from investment funds does not eliminate the problem that the Wall Street firms would still be “too big to fail”.

The issue then is to examine what risk-taking behaviour is worth keeping as legal activity. We ban all sort of risk-taking behaviour (most of which I would allow) so governments around the world are not averse to taking drastic action.

The thing that should be foremost in our minds is what public purpose do these Wall Street capital market monoliths serve? If the answer is very little then they are akin to cars driving too fast on the crowded roads. Fun for the driver – for a while – until a massive pileup is caused. There is no public purpose in allowing the cars to drive fast in the first place. We clearly regulate that severely.

While it is unlikely to happen, I would legislate against derivatives trading other than that which can be shown to be beneficial to the stability of the real economy.

4. Support for household debt restructuring

The IMF say that:

… the government may choose to tackle the problem of household debt directly by setting up frameworks for voluntary out-of-court household debt restructuring-including write-downs-or by initiating government-sponsored debt restructuring programs. Such programs can help restore the ability of borrowers to service their debt, thus preventing the contractionary effects of unnecessary foreclosures and excessive asset price declines.

I agree that this is a suitable role for government to play during a balance sheet recession. However, I do not advocate the government interfering with repossession processes. A private contract is a private contract. But the government should consult with the defaulting private owner to ascertain if they want to keep their house. If so, the government should purchase the house from the bank that is foreclosing at the fire-sale price.

The government should then rent the house back to the former owner for some period – say 5 years. At the end of this period the former owner would be offered first right of refusal to purchase the house at the current market price.

The government would also offer the former owner guaranteed employment in a Job Guarantee, to ensure they are able to pay the rent and reconstruct their personal finances.

This option does involve setting up an administrative process but in terms of the primary goal of a sovereign government to advance public welfare, this proposal is vastly better than the alternative – widespread defaults, fire-sales and banks pursuing homeless indebted people. There is no subsidy operating (market rentals paid, repurchase at prevailing market price); no interference into private contracts, and people stay in their homes.

The IMF thinks these interventions have what they term “limited fiscal cost” and then tells us that the government can actually make profits from purchasing distressed mortgages and on-selling them at a later date.

It is nonsensical to think of a fiat issuing government in this way. As I explained above, the only sensible notion of cost for a government relates to the increased demand on real resources that a specific program entails.

Purchasing distressed mortgages involves some numbers being shifted in sets of accounts within the banking system and the central bank. There is zero “cost” involved. The idea is not that governments “make profit” but that they use their fiscal capacity to advance public purpose.

The problem with the IMF overall analysis, notwithstanding the ill-conceived concept of fiscal sustainability that underpins everything they propose, is that they fail to bring their analysis together. Ideology prevents them from seeing all the interconnections that MMT expound.

For example, in the Chapter section “Factors underlying the buildup in household Debt” they talk about the “increase in credit availability was associated with financial innovation and liberalization and declining lending standards” but fail to demonstrate why this occurred and why the households suddenly developed a thirst for increased credit.

There is no mention of the squeeze on real wages and the massive re-distribution of national income to profits.

In this blog – Questions and Answers 3 – (see Question 6) – I considered why the crisis developed. I had earlier dealt with that question in this blog – The origins of the economic crisis – where I argued that to understand the crisis we have to go back a few decades and trace the development of economic thinking and the subsequent policy changes that have occurred since that time.

By way of summary, the rise of neo-liberalism began around the mid-1970s coinciding with the OPEC oil shocks. Governments, which had previously been committed to maintaining full employment via the use of fiscal and monetary policy (sustained deficits in most cases) – were attacked by free-market economists who promoted the idea that self-regulating markets would provide more stable and better outcomes.

Emerging monetarists such as Milton Friedman were largely opposed to discretionary fiscal policy but their views constituted the minority.

The OPEC-induced inflation shock at that time allowed the monetarist viewpoint to gain ascendancy in the public debate and led to the rejection of activist fiscal policy as the primary policy tool to stabilise spending over the business cycle.

Governments were also pressured to introduce widespread deregulation of the labour and financial markets and to privatise public enterprises and other activities. This was justified by an appeal to textbook economic models which purported to demonstrate that private markets would self-regulate and optimise wealth accumulation for all of us. So all these terms such as “trickle down”, “The Great Moderation”, “the business cycle is dead”, etc became the nomenclature of the era.

One of the main characteristic manifestations of the deregulation was the suppression of real wages growth and a rising gap between labour productivity and real wages. The gap represents profits and so during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital.

Governments around the world helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and attacks on trade unions etc.

The problem then was that if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) was rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) was lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself?

This is especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector since around the mid-1990s in several nations.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumptions goods produced were sold.

But in the recent period, capital found a new way to accomplish this which allowed for the suppression of real wages and increasing shares of the national income produced to emerge as profits.

The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages.

The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing budget surpluses in some nations were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. In many nations the debt was denominated in foreign currencies, which only made the problem worse (and the crash deeper when it came).

The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold. And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base.

Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This is the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

The neo-liberal rhetoric pressured governments to turn a blind eye to the fact that large proportions of the domestic mortgage markets were being financed in foreign currencies, thus exposing householders to exchange rate risk. In some countries this has been catastrophic.

Further, the financial markets lost the capacity to correctly price the risk of the products they were creating and fraudulently entered into agreements with ratings agencies to deceive their clients. So the combination of greed and fraud produce a time bomb.

The combination of a hollowing out of the state, an out of control deregulated financial sector, and the rising fragility of non-government balance sheets thus set up the world economy for the crisis.

The Eurozone countries interpreted the neo-liberal charter in even more extreme ways. They stripped member nations of their currency sovereignty and for ideological reasons (desire to minimise the state) deliberately chose not to create the necessary federal fiscal capacity capable of dealing with asymmetric aggregate demand shocks. They also placed severe restrictions on the fiscal latitude of each of the member states (that is, the Stability and Growth Pact).

The trigger then was the American real estate collapse. What followed was entirely predictable and governments failed to insulate the real economies from the financial disaster that unfolded.

The ideological preference towards monetary policy (a characteristic of the neo-liberal rejection of fiscal activism) meant that even though governments, largely, adopted pragmatic positions as aggregate demand collapsed, they were still unwilling to expand fiscal policy appropriately.

The crisis has endured in many countries, and is now getting worse again, because governments have been pressured into introducing pro-cyclical fiscal policies – that is, fiscal austerity.

They are being beguiled by mainstream economists who claim, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that the private sector (heavily indebted) would suddenly increases spending to offset the decline in public spending.

That hasn’t happened and will not happen.

The crisis represents a fundamental rejection of the neo-liberal vision that self-regulating markets will operate to advance the best interests of all of us. The neo-liberal paradigm fails on every dimension.

A deep understanding of national accounting tells us that the government’s budget outcome will be heavily conditioned by what is going on in the other main sectors – private domestic and external.

As a starting point if the government was to balance its budget over the business cycle, then the private domestic sector balance (the difference between its spending and income) would be equal, on average over the business cycle, to the external balance (the difference between income flows in and out of of the nation).

The import of this is that if a nation was running a continuous external deficit, then the private domestic sector will also, on average, be in deficit. Which means it would be continuously accumulating debt – an unsustainable dynamic.

This does not mean that the household sector, for example, could not reduce its debt levels. The private domestic sector can still be in deficit overall (spending more than it is earning) and the household sector was saving (and thus accumulating the capacity to reduce debt).

But it would mean that the private firms would be accumulating debt and the private domestic sector overall would not be saving.

In this situation, with the household sector deleveraging it is likely that consumption spending will weaken and firms will restrain their investment and the economy will fall into recession unless supported by fiscal policy.

At present the global economy is trapped in a “balance sheet recession”, which has special characteristics and leads to the conclusion that the economy requires long-term public deficit support to achieve sustainable recovery.

We are now in a sustained period of private sector deleveraging, which means that private spending growth has returned to more subdued levels relative to those seen during the credit binge.

That process will extend for at least a decade. Without public deficits supporting aggregate demand growth the economy will languish in stagnation.

Conclusion

The only way that the capitalist system which uses sovereign currencies can grow in a sustainable way without increasing levels of debt being held by the non-government sector is if the government (which maintains a monopoly in the currency issue in their country) maintains budget deficits. The non-government saving are $-for-$ a mirror of the government deficit.

The major take-home point is that governments better get used to running deficits in perpetuity if stability is really going to be achieved.

All through the debt accumulation period (pre-crisis) the IMF was supporting the deregulation orthodoxy. They were active proponents of the view that fiscal surpluses were appropriate even though they were being accompanied (and only were made possible) by the extraordinary escalation of private debt.

It is good that the IMF is now realising that their understanding of the origins of the crisis and why it is enduring was deeply flawed. However, they need to take the next step and abandon their notions of fiscal sustainability to recognise that sustained fiscal deficits are appropriate for most nations and are necessary to allow the private domestic sector to achieve more sustainable balance sheet positions.

The IMF should also abandon its participation in the Eurozone austerity which is killing growth and forcing millions of people to endure unnecessary unemployment. Instead, they should advocate the abandonment of this deeply flawed monetary system, which by design, prevents governments from maintaining policy stances that the IMF now admits are essential for sustained growth.

ITSA Bankruptcy data

The Insolvency and Trustee Service Australia, a government agency “responsible for the administration and regulation of the personal insolvency system in Australia” recently released some experimental data on bankruptcies and debt defaults by postcode.

My research centre – Centre of Full Employment and Equity – has mapped this data and provided map layers to examine connections between unemployment rates and bankruptcies.

The following maps are available for viewing:

- For the 8 Capital Cities – in terms of our classification 54 per cent of the areas are in the same group (high -high etc) for both unemployment rates and bankruptcies.

- Entire Australia-wide dataset – in terms of our classification 46 per cent of the areas are in the same group (high -high etc) for both unemployment rates and bankruptcies.

This data received some belated coverage in the Sydney Morning Herald today (April 11, 2012) – Mounting credit card bills drive bankruptcy boom in western suburbs.

The current push to fiscal austerity by the Federal Government (its obsession with fiscal surpluses) will exacerbate the massive debt burden that Australian households are carrying.

That is enough for today!

Both private debt and gov’t debt is “unsustainable” if the currency printing entity is denied to both of those entities.

“The features of a balance sheet recession are summarised as follows: …”

Zero private debt and zero public debt means no debt defaults and no debt deleveraging.

“The IMF Report concludes that:

In an economy with credit-constrained households, this provides a rationale for temporarily pursuing an expansionary fiscal policy, including through government spending targeted at financially constrained households.

As clear as it could be. Government fiscal expansion is good for an economy where private spending growth lapses. Note this is a different point to whether fiscal deficits should be sustained indefinitely.”

I don’t believe it is that clear. It seems to me you are assuming an aggregate demand shock.

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t (preferably with debt) plus dissavings of the lower and middle class (preferably with debt)

So if the lower and middle class stop going into debt to the rich then the rich (including the IMF) will get the gov’t to go into debt for the lower and middle class.

@Fed Up

No assumption is required. Increased savings rates always come at the expense of aggregate demand unless either the government or foreign sector are net spending.

“I agree that the government is responsible for maintaining financial stability in the monetary system. But that is a separate issue to allow gains to be privatised and losses to be socialised in a capitalist system where risk and return should go together.”

I am not so sure if such issues are just back or white. Let’s say that a government would commit to not socialize losses of financial institutions. That does not mean that those institutions would not take on excessive risk. What it would mean though is that, in order to avoid being taken over by the government (when they faced losses), banks might pursue asset fire-sales and strong credit deleveraging making the situation even worse. A recent example is Europe, where bank capital requirement targets set by European authorities to be effective in mid-2012, pushed European banks to lower available credit to the economy and sell assets.

“Attention should always be focused on what is a reasonable credit risk. In that regard, the banks: […]”

I tend to agree with Gary Gorton on this subject. If regulations and restrictions lower the Return-on-Equity of the official banking sector, the most likely scenario is that credit creation will be moved to the Shadow banking sector. Restrictions might be placed on the terms of the initial loan contract, but limitations on securitization, credit risk insurance will just lower the RoE and move loans to the shadow banking sector.

Securitization is an integral part of the banking and repo sectors and collateral is required in order to provide a ‘deposit insurance’ for deposits over the FDIC limit (which are usually invested in the money market). The sub-prime crisis had its root cause on the fact that sub-prime loans more or less required an appreciating asset price in order for the debtors not to default on their loans. They were speculative by design.

Bill,

Another (additional) solution is for the government, prior to possible repossession, to offer to buy the mortgage itself from the mortgage provider (the bank) at a fire-sale price. That way the contract is now with the government not the bank.

Government can then repossess the persons house in exchange for rent (or repossess just part of it as part of a shared ownership scheme). This seems simpler to me as it gives the government more options.

In a case where the government or the owner can prove the mortgage was mis-sold, or the bank has committed some other breach of the rules, government should have the power of “compulsory purchase” of the mortgage from the provider – again at a fire-sale price.

Kind Regards

Further to my point above: with the mortgage contract now between the owner and the government, the day to day administration of the mortgage can be contracted out to another existing mortgage provider. Thus most of the administration processes are handled by an existing bank, therefore it requires much less government administration. But all the important decisions are taken by the government.

If the government then chooses to repossess the house, then the contracted out bank handles that in the normal way, then the government passes the property to the relevant social housing administrative body who calculate the appropriate rent.

Kostas, In the first part of your comment above you argue that if government makes life harsher for banks, banks will lend less, which will exacerbate the recession and unemployment. Well clearly that is true ALL ELSE EQUAL. And your argument has been put by banks to politicians a hundred times over the last century, and politicians are fooled every time.

But the flaw in the above argument is that all else does not have to be equal. That is, government can perfectly well make up for reduced bank lending by creating new money and spending it into the economy. The stimulatory effect of that cancels out the deflationary effect of less bank lending.

UK bank assets were constant at 50% of GDP 1880 to 1970 and then increased to 500% by 2006 See: p 3. here: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/speeches/2009/speech409.pdf

Exactly what we have gained by this bloated banking industry, I’m not sure: certainly economic growth is no better than it was thirty or forty years ago. Cutting it down to size would do no hard, far as I can see.

Re the shadow banking industry, I am always puzzled as to what is so difficult about regulating it. We just need a law which says that any organisation that does what banks do will be classified as a bank. And that organisation must obey the same rules as banks. Else it’s prison sentences for those running shadow banks.

Bill this is a good post. I had some very interesting and detailed phone conversations with Wynne Godley back in 2005-2006 about the huge buildup of private debt in the US, primarily in the subprime mortgage-related space via the household sector. He particularly wanted to know about the types of loan products that were being offered/hawked to borrowers, all of which were subprime and most of which were in essence toxic to borrowers as well as the ultimate debt holders. Due to his robust sectoral perspective, he spotted the problem quite early. He just knew it would come a cropper and he was of course totally correct. Please keep up the great work!

Could you do a post on the Australian Economy Bill specifically in regard to the following.

Is Australia in a balance sheet deleverage cycle? Perhaps the real-time test will be the continued fall of real estate prices after the next easing in official interest rates? Or does the fact we have had two easings already with real estate prices continuing to fall confirm the deleverage is entrenched? If the lowering of Interest Rates has no effect on real estate prices I guess the cycle is confirmed. How bad will it get given the Aussie household is in record amounts of debt and our Government has made a Political promise to deliver a surplus budget next month?

A complex economic system seems to have no clearly defined cause and effect. It’s just so many influences pushing and pulling that the real direction seems to be masked by the noise. I find it confusing. So many experts and so many vested interests making comments every day. How do we tell what is really going on?

I look forward to the day when the focus is not on budgets but on what really matters, rewarding employment and essential services for all. We need to find a better way to reward brilliance and luck, Other than stealing other peoples sweat equity. Cheers Punchy

Great post Bill. One note. Where you wrote:

A credit crunch emerges – not because there is enough funds but because banks cannot find credit-worthy borrowers to lend to.

I think you meant to say something like …” not because there are not enough funds …”

Some things have not changed that much. Marriner Stoddard Eccles (Chairman US Federal Reserve 1934-48, board member to 1951):

As Eccles wrote in his memoir Beckoning Frontiers (1966):

“As mass production has to be accompanied by mass consumption, mass consumption, in turn, implies a distribution of wealth … to provide men with buying power. … Instead of achieving that kind of distribution, a giant suction pump had by 1929-30 drawn into a few hands an increasing portion of currently produced wealth. … The other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped.”

Thanks Bill

On the part where you describe the functions that banks should be allowed to fulfil, I fully agree with you.

Otherwise an excellent recipe for never ending debt slavery.

Debt that is not repayable within a reasonable period of time, should/must be written off. Any other solution violates basic values which our whole society is built on.

Ben Wolf said: “@Fed Up

No assumption is required. Increased savings rates always come at the expense of aggregate demand unless either the government or foreign sector are net spending.”

Does the gov’t and/or the foreign sector have to “net spend” with debt?

Also, I’d say it definitely matters whether an aggregate demand shock is assumed or something else.

SteveK9 said: “The other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped.”

That is a medium of exchange problem (too much debt), a distribution of medium of exchange problem, a budgeting problem, and a time problem. It sounds very similar to what happened in the last decade.

Instead of saying their credit ran out, I would say when they couldn’t make the interest payments and/or principal payments on the debt. When the people went into debt, they had certain assumptions (whether they realized it or not). When those assumptions did not come true, they defaulted along with the collateral (if any) going down in value.

@Ralph Musgrave

Unfortunately, the credit expansion phase is much longer than the credit contraction phase which is usualy swift and severe with immediate asset fire sales and a major stop on new loans. What basically happened in 2008 was that information-insensitive assets became information-sensitive and market participants tried to move information off their balance sheets by selling assets, increasing haircuts and not extending credit to counterparties with increased risk. I just don’t see how a government commited to taking over failing financial institutions would soften the crisis. What was needed, was for the government/central bank to take risk on its balance sheet in one form or another.

Mind you that i do not advocate the government buying sub-prime loans or guaranteeing bank foreign liabilities (like in Ireland). Speculative behaviour should be punished but government action must be swift and strong, while making sure that markets continue to work properly. The crisis should be dealt first (so that a fair value for assets can be determined) and losses written down only on a second step.

“Re the shadow banking industry, I am always puzzled as to what is so difficult about regulating it. We just need a law which says that any organisation that does what banks do will be classified as a bank. And that organisation must obey the same rules as banks. Else it’s prison sentences for those running shadow banks.”

As Minsky said, ‘everyone can create an IOU, the problem is accepting them’. A supplier extending a 30-day credit to its customer and receiving a 40-day credit from its own supplier can be classified as a bank. Basically, a bank charter provides the holder with the priviledge to be able to leverage its assets with government money (in other words the ability to access the discount window and a bank reserve account), the only liability accepted in all transactions. If the cost of this central bank credit (in terms of capital) is too large, a shadow bank sector will be created one way or another.