I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Fiscal policy is the best counter-stabilisation tool available to any government

In yesterday’s blog – A nation cannot grow without spending – I challenged a view that dominates the European debate which says that fiscal austerity (choking discretionary net public spending) supplemented with vigorous so-called “structural reforms” (aka ransacking wages and working conditions) will promote growth. The corollary of this view is that fiscal austerity alone will fail and the reason Europe is going backwards is not because of the austerity but rather, because the structural reforms process has not been implemented quickly or deeply enough. In all of this there is a basic denial of the fundamental macroeconomic insight – spending equals output which equals income. An economy can only growth if there is spending (aggregate demand) growth. That requires a demand-side solution irrespective of the state of the supply side. Supply improvements might reduce the danger of inflation or improve the quality of output but people still have to purchase the output for growth and innovation to persist. A related argument is that fiscal stimulus aimed at fostering growth will cause inflation and be self-defeating. This view prevails in mainstream macroeconomics as taught in the universities of the world. Some mainstream economists do qualify this view and give conditional support to the fiscal stimulus solution by appealing to what they term the “liquidity trap”. This blog is about that argument.

Mainstream economists such as Paul Krugman have been strong supporters of the idea that more fiscal stimulus is necessary in most economies at present. The subject of yesterday’s blog – Chicago economist John Cochrane said in his article – Austerity or stimulus? What’s needed in the US is structural reform – “Why is austerity causing such economic difficulty? Lack of “stimulus” is the problem, say the Keynesians, epitomised by the economist Paul Krugman”.

In ordinary times, Paul Krugman and his ilk would consider that fiscal stimulus would increase interest rates and crowd out private investment spending (the “crowding out” hypothesis). He considers the present situation to be a “special case”.

In this article (October 9, 2011) – IS-LMentary – he outlined the so-called IS-LM model that used to be the main vehicle to facilitate mainstream explanations of interest rate and output determination. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents reject the model at its most elemental level and Randy Wray and I will not be covering it in our up-coming textbook.

But the fact that Paul Krugman uses the framework as a vehicle for explaining macroeconomics places him very firmly in the mainstream camp. He wrote:

Yes, IS-LM simplifies things a lot … But it has done what good economic models are supposed to do: make sense of what we see, and make highly useful predictions about what would happen in unusual circumstances. Economists who understand IS-LM have done vastly better in tracking our current crisis than people who don’t.

Apparently, the IS-LM model allowed Paul Krugman to reject the constant claims “in early 2009” by the “WSJ, the Austrians, and the other usual suspects” who “were screaming about soaring rates and runaway inflation”.

Apparently, “those who understood IS-LM were predicting that interest rates would stay low and that even a tripling of the monetary base would not be inflationary. Events since then have, as I see it, been a huge vindication for the IS-LM types …”

He said that:

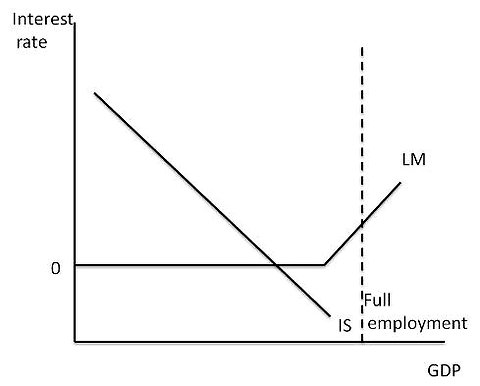

Most spectacularly, IS-LM turns out to be very useful for thinking about extreme conditions like the present, in which private demand has fallen so far that the economy remains depressed even at a zero interest rate. In that case the picture looks like this:

By way of simple explanation, the LM curve describes all combinations of interest rates (vertical axis) and GDP (horizontal axis) where money demand and money supply are equal. The usual assumption is that the central bank can control the money supply and that money demand varies inversely with the interest rate because there is an opportunity cost in holding money at high interest rates given cash earns nothing.

So individuals have a choice in this framework between holding an interest-earning government bond or a non-interest bearing cash balance and so variations in the interest rate alter their portfolio (more bonds at higher interest rates).

Money demand is also considered to be a positive function of the level of income (the so-called “transactions motive” for holding money balances).

The upshot is that the LM curve is usually depicted as being upward sloping.

Here is Paul Krugman’s explanation:

… people deciding how to allocate their wealth are making tradeoffs between money and bonds. There’s a downward-sloping demand for money – the higher the interest rate, the more people will skimp on liquidity in favor of higher returns. Suppose temporarily that the Fed holds the money supply fixed; in that case the interest rate must be such as to match that demand to the quantity of money. And the Fed can move the interest rate by changing the money supply: increase the supply of money and the interest rate must fall to induce people to hold a larger quantity.

Here too, however, GDP must be taken into account: a higher level of GDP will mean more transactions, and hence higher demand for money, other things equal. So higher GDP will mean that the interest rate needed to match supply and demand for money must rise. This means that like loanable funds, liquidity preference doesn’t determine the interest rate per se; it defines a set of possible combinations of the interest rate and GDP – the LM curve.

The IS-curve shows all the combinations of interest rates and income where aggregate spending equals aggregate output (demand equals supply) – that is, product market equilibrium. The motivation for the IS curve being typically depicted as downward sloping is that investment spending is considered to be inversely related to the interest rate (rising cost of borrowing chokes off marginal projects). Rising government spending pushes the IS curve out (other things equal) and austerity pushes it in.

The combination of all these interactions then is summarised by the IS-LM intersection which tells us the rate of interest and income where both the money and product markets are in equilibrium.

The pedagogy involved in relating the IS-LM story accurately to students takes several weeks of an intermediate macroeconomic subject. You can outline the model more quickly but then the students typically get lost because it takes some time for them to appreciate what two “equilibrium” relationships drawn in the same space and creating a macro equilibrium actually means.

At the end of the time, one achieves very little using this framework. It just says that increasing spending with a fixed money supply will drive up interest rates and income depending on the relative slopes of the IS and LM curves. It doesn’t say much about the way the actual monetary system works.

So students rehearse extreme cases involving horizontal and vertical curves and everything in between but typically get lost.

The diagram provided by Paul Krugman (above) is a special case of the model where, for a certain level of income (low), the LM curve is horizontal. What does that mean in English? Paul Krugman explains his own diagram as follows:

Why is the LM curve flat at zero? Because if the interest rate fell below zero, people would just hold cash instead of bonds. At the margin, then, money is just being held as a store of value, and changes in the money supply have no effect. This is, of course, the liquidity trap.

And IS-LM makes some predictions about what happens in the liquidity trap. Budget deficits shift IS to the right; in the liquidity trap that has no effect on the interest rate. Increases in the money supply do nothing at all.

There are several points to be made. It was interesting that Paul Krugman defined the Liquidity trap in this way – “people would just hold cash instead of bonds”.

We have heard the term liquidity trap a lot in the last few years. It is used to describe the current situation where monetary policy becomes ineffective at very low interest rates because everyone will hold every extra dollar introduced into the economy as demand balances.

In 1937, John Hicks noted the liquidity trap was “a special form of Mr. Keynes’s theory” because it coincided with a state where the demand for money was not sensitive to income levels and/or was highly sensitive to interest rate changes. People demanded cash holdings as a buffer against interest rate uncertainty (given they could hold interest-bearing bonds as an alternative source of wealth).

The model assumed that under normal conditions interest rates fall if the money supply rises because people have to be induced to hold the extra cash and will only do this if the opportunity cost of hold non-interest bearing cash is lower.

At some level of interest rates, everyone will expect rates to rise and thus bond prices to fall and so no-one will invest in bonds in expectation of suffering capital losses. This is the notion of a liquidity trap. According to the logic, monetary policy (represented in this debate as variations in the money supply) will have no impact on aggregate demand because people will be prepared to hold all new money as cash.

The liquidity trap concept was used by Keynes to refute the classical claims that a reduction in nominal wages and prices would benefit the economy. The point of the liquidity trap in relation to flexibility of prices was that if money wages and prices fell (but the real wage was unaltered) the real money supply was still higher (actual real value of the money stock). Normally this would drive down interest rates as above, which would according to their logic stimulate aggregate demand.

Keynes was fully aware of this hypothetical source of stimulus and was termed “the Keynes effect”. The mainstream considered this to be the normal situation. But when there was a liquidity trap this effect could not work because interest rates did not respond to changes in the real money supply.

There were other related debates in this regard (for example, the 1947 observation by Tobin that the Keynes effect would be stifled because investment was not very sensitive to interest rate changes). In the IS-LM parlance, this means that the IS curve is very steep if not vertical. This is a major criticism of the IS-LM approach. Investment spending now or next period is typically the result of decisions taken some periods ago given the time lags involved in project evaluation, design, financing and implementation.

So current investment spending is likely to have no sensitivity to interest rate movements meaning the IS curve (if it was a valid construction anyway) would be vertical – which would mean that monetary policy changes designed to change the interest rate would never change the level of real GDP (that is, monetary policy would be totally ineffective).

This is fairly close to the standard Post Keynesian position on the relative effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy.

The context of all this was the mainstream attack on Keynes centred on his logic only applying in special cases – money wage rigidity; liquidity trap etc. The pragramatic Keynesians, argued that inasmuch as these rigidities were operative real world constraints, there was still a justification for using aggregate demand policies (like a fiscal stimulus) to push the economy out of an underemployment equilibrium.

This is the current line taken by Paul Krugman and others who consider the current situation depicts a liquidity trap.

So, while not conceding the point that the whole Keynesian attack on the mainstream classical model rested on the existence of these special cases, there was still a pragmatic policy argument to be made supporting discretionary fiscal intervention.

But the approach was challenged by the next mainstream (pro-market) attack on Keynes which centred on the existence and strength of the so-called real balance effect (wealth effect).

Several writers contributed to this literature but the most famous were the following three papers by Arthur Pigou:

- Employment and Equilibrium, 1941

- ‘The Classical Stationary State’, 1943, Economic Journal, 53(4), 243-51.

- ‘Economic Progress in a Stable Environment’, Economica, 14, 180-88.

These contributions attempted to enrich the specification of the Keynesian consumption function that hitherto had been specified in terms of income and interest rates. So rising disposable income stimulated consumption via the marginal propensity to consume whereas rising interest rates reduced consumption because they reduced the opportunity cost of saving (and hence favoured future consumption).

Pigou and others claimed that in addition to these influences, consumption was a positive function of real net wealth which he defined as the real supply of money and the real supply of public debt.

The importance of this argument should be obvious. Even if all the other sources of mainstream market-based recoveries are not forthcoming when wages and prices fall, the lower prices deliver these positive wealth effects on consumption.

In other words, a consumption-led recovery can occur when there is deflation. This effect was called the Pigou or Real Balance effect. Importantly, Pigou believed that the existence of a liquidity trap was non binding and that rising consumption would restore full employment as long as wages and prices were flexible.

So he argued that ultimately, mass unemployment arose because of nominal wage rigidities and the solution to a recession was to cut wages. The British government and some of the EMU nations clearly have been thinking along these lines.

There were logical difficulties in actually constructing the case. The argument did not imply that consumers ran down their wealth holdings to finance their additional consumption. It was clearly acknowledged that this would require a sale of assets to another individual which may be problematic in a deep recession.

The argument introduced ad hoc psychic notions that by feeling richer (in real terms), consumers were emboldened to consume more out of their current income.

There was tension within the mainstream paradigm (see the 1951 article by Lloyd Metzler, ‘Wealth, Saving and the Rate of Interest’, Journal of Political Economy, 59(2), 93-116) who argued that in one fell stroke, while Pigou had restated the automatic tendency of the economy to full employment, he has also rendered the classical dichotomy whereby increases in the money supply could not have real effects (that is, the argument that aggregate monetary policy interventions were ineffective) implausible.

A major attack on Pigou’s idea came from in Michal Kalecki’s 1944 article (‘Professor Pigou on the Classical Stationary State: A comment’, Economic Journal, 54, 131-2) where he distinguished between “inside” and “outside” money and wealth. If you have access to JSTOR, you can read the article HERE.

Kalecki says that Pigou’s claim that the market-economy will tend to full employment is based on his assumption that:

… the stock of money is constant, and thus its real value increases in the course of the wage fall. Thus, argues Professor Pigou, the real value of existing possessions increases. The richer people are, however, the less they are willing to save out of a given real income. Thus if the increase in the real value of the stock of money reaches a certain limit, people will save nothing out of real incomes corresponding to full employment. At that point full employment long-run equilibrium will be reached.

Kalecki then provided his fundamental critique of this notion:

The increase in the real value of the stock of money does not mean a rise in the total real value of possessions if all the money (cash and deposits) is “backed” by credits to persons and firms, i.e. if all the assets of the banking system consist of such credits. For in this case, to the gain of money holders there corresponds an equal loss of the bank debtors. The total real value of possessions increases only to the extent to which money is backed by gold. In other words, the total real value of possessions increases as a result of the wage-fall only by the increase in the real value of gold. If in the initial position the stock of gold is small as compared with the national wealth, it will take an enormous fall in wage rates and prices to reach the point when saving out of the full employment income is zero. The adjustment required would increase catastrophically the real value of debts, and would consequently lead to wholesale bankruptcy and a ” confidence crisis.” The ” adjustment ” would probably never be carried to the end: if the workers persisted in their game of unrestricted competition, the Government would introduce a wage stop under the pressure of employers.

So “inside” money (bank deposits) and inside wealth (private sector debt) are not net wealth. In MMT, we note that all horizontal transactions net to zero because an asset held by a private entity always is matched by a corresponding liability in the private sector. In other words, once you aggregate, all “inside” debts net to zero.

Please read the suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more information on the difference between horizontal transactions within the non-government sector and vertical transactions between the government and non-government sectors which do not net to zero.

Kalecki understood this point. His argument is that the Pigou effect could only be conceived in terms of “outside” money (base money and reserves) and outside wealth (government bonds). This is because there are no corresponding liabilities to these assets. So Kalecki was arguing that the size of the effect would be significantly smaller in practice.

The empirical relevance of these wealth effects has also been questioned. While most economists (me included) will acknowledge that conceptually they might occur the studies that have sought to estimate the magnitude of the real balance effects all show them to be very small. So small that their practical significance in restoring full employment when a deep recession occurs is zero.

In his famous 1956 American Economic Review article – A Macroeconomic Approach to the Theory of Wages (46(5), 835-856) – one of the early Post Keynesians, Sidney Weintraub discussed the likely relationship between wage and the demand for labour. Reflecting on the claim that lowering the wage would stimulate the Pigou effect, Weintraub said:

As an extreme illustration to make the point, though a cruel and prohibitive one from a policy standpoint, when prices fall to such levels that those owning “pennies” become “millionaires” – a calamitous prospect! – full employment may well be assured … For example, to hazard a crude guess, in the current economy … to be effective the real-asset influence on consumption might require a price fall extending beyond 50 per cent.

If you have JSTOR access you can read this article HERE.

In another article, referred to above, Weintraub said:

Many post Keynesians would argue that the real-balance effect is a weak reed for restoring full employment in a contract-using monetararized economy, and to rely on it would compel prices to plunge so dramatically as to invite universal bankruptcy, spelling pauperism and an ominous enlargement of the army of unemployed. The chain of events is more conducive to street riots and a spirit of revolt, rather than for creating a favorable investment climate. A transformation of capitalism, rather than an era of full employment, would seem to be a superior prediction.

So the estimated impacts of wealth effects operating through consumption been found to be tiny in the usual range that prices might be expected to fall. This means that to have any impact of significance, prices would have to fall dramatically and this would not only be destabilising but improbable.

The classic Keynesian notion of the Liquidity trap was based on the portfolio preferences of individuals – as Krugman acknowledges in his quote.

It also assumed that the central bank could control the money supply via movements in the monetary base. That is, there is a money multiplier concept tied in with it. Neither assumption holds water in the real world.

The central bank cannot control the money supply and there is no money multiplier. Please read my blogs – Money multiplier and other myths and Money multiplier – missing feared dead – for more discussion on this point.

Using this conception of the liquidity trap we would expect to see the demand for government bonds falling off (and auctions failing). However, it is clear from the behavour of yields that demand for bonds is very high at present in most nations, even though a reasonable expectation is that interest rates will only rise.

If people realise that interest rates can only go up (thereby guaranteeing capital losses on their bond holdings) why would they be demanding bonds? The answer is difficult to provide because it goes tot he psychology of the bond investors but what it tells us is that the current situation is not a liquidity trap of the type Keynes envisaged.

For many years, the concept of a liquidity trap was not promoted in discussions by economists (mainly because growth was relatively strong).

However, more recently, in the early 1990s, we saw a revival of the concept when the Japanese property market collapsed and the Bank of Japan held their target rate at zero for the next two decades (or thereabouts).

The low interest rates (zero or near zero) and stagnant real GDP growth was termed a liquidity trap, The demand for Japanese government bonds remained strong throughout this period as budget deficits rose to maintain some support for the real economy. This was not a classic Keynesian liquidity trap.

So the term has been bastardised by Paul Krugman and others to refer to the “presence of zero interest rates (ZIRP)’ and the claim that because interest rates cannot be negative “monetary policy would prove impotent”.

The link between the two concepts is that at low interest rates, monetary policy becomes ineffective and fiscal stimulus is required to kick-start the economy.

In this article (March 17, 2010) – How Much Of The World Is In a Liquidity Trap? – Paul Krugman says that

In my analysis, you’re in a liquidity trap when conventional open-market operations – purchases of short-term government debt by the central bank – have lost traction, because short-term rates are close to zero.

This is a completely mainstream view of the way the monetary system operates. The central bank is deemed to control the money supply by buying and selling government bonds, which in turn, influences the interest rate. When there is no longer any capacity to influence the interest rate because everybody is holding cash and refusing to hold bonds, monetary policy can no longer alter the interest rate.

However, the central bank adjusts the interest rate by managing the reserves in the banking system, knowing that it cannot control the money supply. It keeps the interest rate at close to zero by leaving excess reserves in the system (just as the Bank of Japan has been doing for two decades or so).

This is not the Keynesian liquidity trap.

It is also interesting to note that Paul Krugman didn’t always think like this.

In the late 1990s, he joined a number of academic economists in urging the Bank of Japan to introduce large-scale quantitative easing to kick start the economy. The Bank, reluctantly, heeded their advice and in 2001 they increased bank reserves from ¥5 trillion to ¥30 trillion. This action had very little impact – real economic activity and asset prices continued their downward spiral and inflation headed below the zero line.

Many economists had also claimed that the huge increase in bank reserves would be inflationary. They were also wrong. Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

In this 1998 article on Japan’s trap, Krugman claimed that Japan was “in the dreaded “liquidity trap”, in which monetary policy becomes ineffective because you can’t push interest rates below zero”. This is similar to the argument he is making about the US at present.

He said that when the nominal interest rate is at zero and therefore stimulatory interest rate adjustments can no longer be made, the real rate of interest that is required to “match saving and investment may well be negative” (as an aside – this sort of reasoning is derived from the highly flawed loanable funds doctrine).

As a Keynesian, he recognised that there was a spending gap in Japan at the time and while fiscal policy would possibly work it is constrained by “a government fiscal constraint” and further that the Japanese Government would only be wasting its spending on “roads to nowhere”.

So he then considered monetary policy as the best way forward. In that context, Krugman says that the nation needs a dose of expected inflation so that the real interest rate becomes negative (and flexible). He concluded that monetary policy had been ineffective because:

… private actors view its … [Bank of Japan] … actions as temporary, because they believe that the central bank is committed to price stability as a long-run goal. And that is why monetary policy is ineffective! Japan has been unable to get its economy moving precisely because the market regards the central bank as being responsible, and expects it to rein in the money supply if the price level starts to rise. The way to make monetary policy effective, then, is for the central bank to credibly promise to be irresponsible – to make a persuasive case that it will permit inflation to occur, thereby producing the negative real interest rates the economy needs. This sounds funny as well as perverse. … [but] … the only way to expand the economy is to reduce the real interest rate; and the only way to do that is to create expectations of inflation.

He was incorrect in making this diagnosis. The only thing that got Japan moving again in the early part of this Century was a dramatic expansion of fiscal policy.

In another related article Paul Krugman elaborated on quantitative easing. He said:

The Bank of Japan has repeatedly argued against such easing, arguing that it will be ineffective – that the excess liquidity will simply be held by banks or possibly individuals, with no effect on spending – and has often seemed to convey the impression that this is an argument against any kind of monetary solution.

It is, or should be, immediately obvious from our analysis that in a direct sense the BOJ argument is quite correct. No matter how much the monetary base increases, as long as expectations are not affected it will simply be a swap of one zero-interest asset for another, with no real effects. A side implication of this analysis … is that the central bank may literally be unable to affect broader monetary aggregates: since the volume of credit is a real variable, and like everything else will be unaffected by a swap that does not change expectations, aggregates that consist mainly of inside money that is the counterpart of credit may be as immune to monetary expansion as everything else.

But this argument against the effectiveness of quantitative easing is simply irrelevant to arguments that focus on the expectational effects of monetary policy. And quantitative easing could play an important role in changing expectations; a central bank that tries to promise future inflation will be more credible if it puts its (freshly printed) money where its mouth is.

So once again he is claiming that an expansion of reserves will increase bank loans because he asserts it will be inflationary and alter the drive the real interest rate into the negative domain.

Conclusion

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not rely on the existence of a “liquidity trap” (however conceived) to make a case for the effectiveness of fiscal policy. Paul Krugman and others, who currently advocate the the use of fiscal policy, only do so because they claim there is a liquidity trap which renders monetary policy ineffective. However, in normal times they advocated the primacy of monetary policy.

MMT can demonstrate the ineffectiveness of monetary policy outside of a liquidity trap. The reality is that policy makers have very little idea of the speed and magnitude of monetary policy impacts (interest rate changes) on aggregate demand. There are complex timing lags given how indirect the policy instrument is in relation to its capacity to influence final spending.

Further there are unclear distributional effects – creditors gain when rates rise, debtors lose. What will be the net effect? Central bankers do not know the answer to that question.

Monetary policy is also a blunt policy instrument that has no capacity to target specific segments of the spending population or regions.

We always knew that. The reason the mainstream promoted monetary policy to the fore was because they were really advocating smaller government and more free market space. Hence they had to undermine the case for fiscal policy. In doing so, they have created three or more decades of persistent underutilisation of labour resources in most nations; virtually zero growth in per capita incomes in the poorest nations; and set the World up for the current crisis.

By continuing to see quantitative easing as the solution, the more progressive mainstream economists have also caused the current crisis to be extended.

Fiscal policy expansion is always indicated when there is a spending gap. It is a direct policy tool ($s enter the economy immediately) and can be calibrated and targetted with more certain time lags. Liquidity trap or not, fiscal policy is the best counter-stabilisation tool available to any government.

That is (more than) enough for today!

“Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents reject the model at its most elemental level ”

So did Hicks who created the thing.

And Steve Keen points out that the mechanism used to eliminate the Labour market cannot be used in a non-Walrasian world – ie one that has credit money like we do.

Why does an incorrect model persist long after it has been empirically demolished.

Is it that neo-classical economists want the world to be like this and prefer to model their fantasy?

” This is because there are no corresponding liabilities to these assets. ”

Should that be ‘no corresponding liabilities to these assets held in the non-government sector’?

There’s a liability held by the government sector – even if it’s just a notional accounting liability.

“to rely on it would compel prices to plunge so dramatically as to invite universal bankruptcy, spelling pauperism and an ominous enlargement of the army of unemployed. The chain of events is more conducive to street riots and a spirit of revolt, rather than for creating a favorable investment climate. A transformation of capitalism, rather than an era of full employment, would seem to be a superior prediction.”

So is this the policy approach in Greece and Ireland? Are they trying to trigger the ‘real wealth effect’ there?

I am not aware of anyone on the domestic policy scene who resorts to IS-LM. Today’s post was interesting as far as a theoretical discussion goes.

“The reason the mainstream promoted monetary policy to the fore was because they were really advocating smaller government and more free market space. ”

The other line I’ve seen on that is that economists wanted the economy run by somebody other than politicians. So they installed a bunch of economic technocrats in the central bank who were supposed to pull the levers and make everything wonderful – Wizard of Oz style.

The government meanwhile was sidelined into its own little box and turned into a currency user so that they would be constrained and unable to spend more than they ‘earned’ – supposedly preventing the destabilising ‘buying votes’ routine.

Unfortunately the plan didn’t turn out like that. Unsurprisingly when you put a bunch of bankers in charge of the economy, they run policy for the benefit of the bankers.

So one of the problems we have is how to get the economy run for the benefit of the voters again.

Dear Bill

Shouldn’t that be counter-cyclical tool or stabilization tool?

Do you consider tax cuts to be a fiscal stimulus? The beauty about tax cuts is that the government hasn’t to think about projects on which to spend the stimulus money. Of course, those tax cuts have to be for people with low and modest incomes, the ones who are likely to spend the money.

Regards. James

I got this feeling that left-wing economists don’t want to acknowledge real-balance effect because it lays credibility to the argument that wage falls could be good thing for the employment, while right-wing economists do not wanna acknowledge it because leads to argument that people need wealth – even poor people need wealth – in order to economy to function properly.

So they both play it down!

Bill,

Apparently the Bank of England has done some new research which you might want to coment on if you have the time. Robert Peston of the BBC has discussed this today in his blog:

I can’t find the original analysis by the BoE, but here is a link to Robert’s blog:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-17523376

Kind Regards

Bill,

Really great piece. You might be interested to know that when analysing Japan Krugman originally thought the Pigou effect was going to have some consequence.

http://www.pkarchive.org/japan/japtrap2.html

“If you really want to know, I had initially believed that the ‘Pigou effect’ might play an important role in the discussion, and needed the intertemporal model to convince myself that it did not.”

Krugman still does not, in my opinion, have a strong grasp of how deflationary forces operate. You can see this very clearly in his newish paper on debt deflation and Minsky that Steve Keen did a great critique of here:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2011/03/04/%E2%80%9Clike-a-dog-walking-on-its-hind-legs%E2%80%9D-krugman%E2%80%99s-minsky-model/

Prof. Mitchell:

“Fiscal policy expansion is always indicated when there is a spending gap. It is a direct policy tool ($s enter the economy immediately) and can be calibrated and targetted with more certain time lags. Liquidity trap or not, fiscal policy is the best counter-stabilisation tool available to any government.”

And I see the concept of permanent Job Guarantee Program like cancer defeating medication which targets precisely the cancerous cells at all times, killing and not allowing them to ever grow again.

Krugman, doesn’t understand debt (both private and gov’t), banking, and accounting?

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/27/minksy-and-methodology-wonkish/

“In particular, he asserts that putting banks in the story is essential. Now, I’m all for including the banking sector in stories where it’s relevant; but why is it so crucial to a story about debt and leverage?”

And, “Keen then goes on to assert that lending is, by definition (at least as I understand it), an addition to aggregate demand. I guess I don’t get that at all. If I decide to cut back on my spending and stash the funds in a bank, which lends them out to someone else, this doesn’t have to represent a net increase in demand.”

Not how banks work assuming “stash the funds in a bank” means a checking account?

MMT can demonstrate the ineffectiveness of monetary policy outside of a liquidity trap.

Monetary policy has been shown to be effective in controlling inflation in substancially dollarized non-US economies.

Further there are unclear distributional effects

Aren’t the distributional effects of fiscal policy also unclear?

Fed Up,

“If I decide to cut back on my spending and stash the funds in a bank, which lends them out to someone else, this doesn’t have to represent a net increase in demand.”

Banks don’t lend deposits. Loans create deposits, not the other way round.

Bank loans create deposits, but bank lending is only about 25% of total lending in the US.

The remaining 75% is deposits being loaned in the loanable funds market.

So why should it really matter if deposits are created or loaned?

“So why should it really matter if deposits are created or loaned?”

Markets are made on the margins.

Creation allows more spending than has been earned via production – and that drives the bubble factory.

Banks buffer. The temporal difference between injection and withdrawal – which neo-classicals see as co-incident – is utterly crucial to the dynamics of the economy.

CharlesJ, I would say banks don’t lend deposits from a checking account or a CD.

MamMoTh said: “So why should it really matter if deposits are created or loaned?”

If I save $10 then loan the $10 to a friend who spends it, the amount of medium of exchange in circulation is unchanged at that present moment. The created way allows the amount of medium of exchange in circulation to increase at that present moment.