I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

The nearly infinite capacity of the US government to spend

I was examining the latest US Federal Reserve Flow of Funds data the other day. This data comes out on a quarterly basis with the latest publication being March 8, 2012. Other related data from the US Treasury (noted below) fills out the picture. The data reveals some interesting trends in terms of US federal government debt issuance over the last 12 months. It shows that the dominant majority of federal debt issued in 2011 was purchased by the US Federal Reserve. Some conservative commentators have expressed horror about this trend. As a proponent of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) I simply note that the trend demonstrates the nearly infinite capacity of the US government to spend.

There are a few data sets that you can pull together to break the total US public debt outstanding into various categories. The US Treasury Department provides an extensive data resource – for example, Ownership of Federal Securities. The US Treasury also provide data which provides a Foreign breakdown.

The US Federal Reserve provides Consolidated Balance Sheet data.

I last analysed this issue in this blog – When the government owes itself $US1.6 trillion.

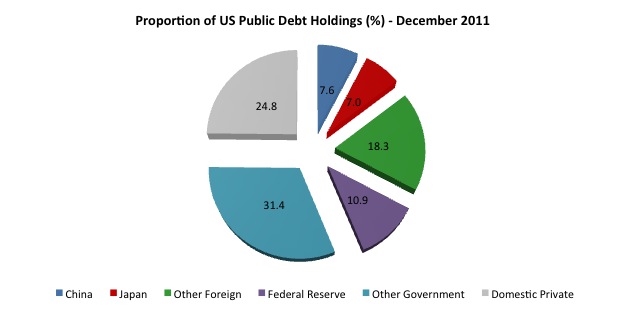

The following pie-chart is the result of some calculations as at December 2011. It shows the proportions of total US Public Debt held by various “interesting” categories. This chart tells you that the government sector held about 42.3 per cent of its own debt in December 2011 and the private sector held the rest.

The scare-mongering campaign that has been waged by the deficit terrorists in recent years holds out that US public debt holdings are dominated by the Chinese. If you call 7.6 per cent (and falling) a domination share then your sense of calibration is different to mine. The three largest foreign US debt holders at December 2011 are China (7.6 per cent); Japan (7 per cent) and the Oil Exporters (1.7 per cent). The Oil Exporters include (Ecuador, Venezuela, Indonesia, Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Gabon, Libya, and Nigeria)

The impact of the British austerity is noticeable. In March 2011, Britain was the third largest holder of US public debt (at 2.3 per cent of total US public debt) and by December 2012, this had dropped to 0.7 per cent (they shed $US212 billion worth of US treasury securities in that 6 month period).383661357.7 of total foreign holdings).

The total foreign held share of outstanding US public debt was equal to 32.9 per cent in December 2011 – a relatively stable proportion.

I often get asked about foreign holdings of US government debt. There is general alarm that somehow China is keeping the US government from insolvency and if they stop purchasing US treasury securities then the US government will go broke.

We always have to go back to first principles to understand what is going on. Even though China currently (as at January 2012) holds some $US 1159.5 billion worth of US government securities, the fact remains that the US government really only owes the Chinese holders of these instruments the regular interest payments that are associated with the particular security.

What do I mean by that? If you think about it, these bond holders purchased the bonds with US dollars that they had gained from trade surpluses with the US (and elsewhere). The Chinese preferred to have the US dollars than the real goods and services they shipped to US consumers and firms in exchange for them.

Which side of the deal got the better outcome? It depends on whether you value real goods and services or bits of paper more!

The point is that the US dollars earned by the Chinese as exporters were sitting in US bank accounts and the holders of the deposits decided to convert them into interest-earning assets by buying bonds. One US-dollar bank account was reduced (as the withdrawals to pay for the bonds occurred) and another US-dollar bank account (at the Federal Reserve) was opened – the payment for the bonds.

The Federal Reserve at some point will instruct some accounts operative to transfer funds from the “Public Debt Account” to the holders private account once the bond matures and add some interest.

There was also a recent Federal Reserve research paper – Foreign Holdings of U.S. Treasuries and U.S. Treasury Yields – (which I will report on more fully another day).

The paper’s main research question was:

Would a slowing of foreign official purchases of Treasury notes and bonds affect long-term Treasury yields?

The paper said that most of the growth in foreign holdings of US treasuries came from nations “running large current account surpluses” as I have noted above.

The question is whether a marked slowdown in these purchases would have a major impact on US Treasury Security yields. They concluded that if the foreign holdings fell by $US100 billion in a month (about a 2 per cent decline – which would be a major shift by historical standards) then the yields on 5-year bonds would rise in the long-run by “about 20 basis points”.

In other words, hardly at all. I hope all the scaremongers read that paper and absorb its findings. Should they be able to read technical papers that is! (me being mean!)

The US Federal Reserve held 10.9 per cent of total US public debt in December 2011 – that is, more than China (at 7.6 per cent). The total holdings were around $US 1,274,274 million.

According to the US Treasury the total outstanding US public debt on March 26, 2012 was $US15,586,074.5 million, which means the US Federal Reserve holdings (latest data March 22, 2012 – $US1,662,477 millions) represent around 10.6 per cent of the total outstanding US public debt.

Since January 7, 2010 the US Federal Reserve has increased its public debt holdings from $US 776,591 million to $US1,662,477 million (as at March 22, 2012) a change of $US885,886 million, whereas total US public debt has risen from $US12,280,845 million to $US15,584,905.8 million – a change of $US 3,304,060.8 million).

In other words, the US central bank has accounted for 27 per cent of the rise in US public debt – the dominant source.

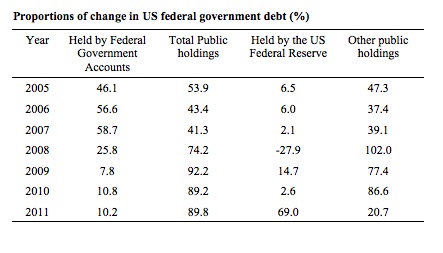

However, the data for 2011 is even more stark. The following Table shows the proportions of the total change in US federal government debt for the calendar years 2005 to 2011 accounted for by the main holders – Other Federal Government Agencies, Total non-government (public), which is, in turn, split between Federal Reserve holdings and other non-government.

In 2011, the increases in the US Federal Reserve’s holdings accounted for 69 per cent of the total increase in US federal government debt.

There was a dramatic shift in the mix of debt holders other than Federal Government accounts in 2011.

Given the change in US Federal Reserve holdings over the last year or more one might easily conclude that the US government (consolidated Treasury and central bank) is its largest lender. That is, the Government borrowing from itself!

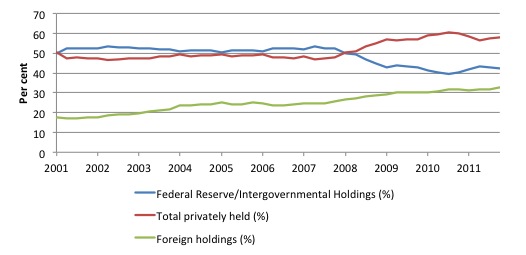

The next graph shows the evolution from March 2001 to December 2011 of the US public debt by private, public and foreign holdings (%). The foreign holdings are a subset of the private series.

There are some interesting points to note. At a time when the US public debt ratio has risen beyond what the mainstream claim is the danger point (80 per cent) – the point where they claim governments become insolvent (Rogoff and co), the private demand for US public debt has risen. Private markets know that there is no substantive default risk involved in holding the US Treasury debt.

The other point, in relation to the rising foreign share is that you cannot conclude that the foreigners (China, Japan etc) are “funding” the US government. The US government is the only government that issues US currency so it is impossible for the Chinese to “fund” US government spending. To understand the trend shown in the graph more fully we need to appreciate that the rising proportion of foreign-held US public debt is a direct result of the trade patterns between the countries involved (and cross trade positions) – as explained above.

For example, China will automatically accumulate US-dollar denominated claims as a result of it running a current account surplus against the US. These claims are held within the US banking system somewhere and can manifest as US-dollar deposits or interest-bearing bonds. The difference is really immaterial to US government spending and in an accounting sense just involves adjustments in the banking system.

The accumulation of these US-dollar denominated assets is the “reward” that the Chinese (or other foreigners) get for shipping real goods and services to the US (principally) in exchange for less real goods and services from the US. Given real living standards are based on access to real goods and services, you can work out who is on top (from a macroeconomic perspective).

Note that a worker in Detroit who is suffering from unemployment as a result of cheaper imports coming from nations with lower labour standards (pay and conditions) than the US is unlikely to agree with me. In his/her case I wouldn’t agree with me either. But I am writing as a macroeconomist here without regard to equity which isn’t to say that equity isn’t a crucial policy aim as well.

In the context of this data, there was an alarmist sort of article in the Wall Street Journal today (March , 2012) – Demand for U.S. Debt Is Not Limitless – written by a former US Treasury official, one Lawrence Goodman.

He is horrified at the current trends. He says that:

The conventional wisdom that nearly infinite demand exists for U.S. Treasury debt is flawed and especially dangerous at a time of record U.S. sovereign debt issuance.

The recently released Federal Reserve Flow of Funds report for all of 2011 reveals that Federal Reserve purchases of Treasury debt mask reduced demand for U.S. sovereign obligations. Last year the Fed purchased a stunning 61% of the total net Treasury issuance, up from negligible amounts prior to the 2008 financial crisis. This not only creates the false appearance of limitless demand for U.S. debt but also blunts any sense of urgency to reduce supersized budget deficits.

In fact, the data suggests the proportion is slightly higher but then that would be quibbling.

The point is that Lawrence Goodman is clearly starting out from an ideologically-biased standpoint. When he is talking about “nearly infinite demand” he is restricting his definition of “purchasers” to the private bond markets.

He clearly hates the reality that the total demand for US federal government debt is comprised of private bond market demand and demand from the “Federal Reserve and Intragovernmental holdings” (that is, the US government itself).

Once we take into account that reality (rather than his ideological desire) then there is clearly nearly infinite demand for the US government debt. The US Federal Reserve has no effective limits on its holdings or purchasing capacity.

Lawrence Goodman also chooses to represent voluntary accounting regulations as financial constraints – a myth that MMT always seeks to expose and highlight.

He says:

It is true that the U.S. government has never been more dependent on financial markets to pay its bills. The net issuance of Treasury securities is now a whopping 8.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) on average per annum-more than double its pre-crisis historical peak. The net issuance of Treasury securities to cover budget deficits has typically been a mere 0.6% to 3.9% of GDP on average for each decade dating back to the 1950s.

The “net issuance” figures are no surprise given the output gap that the US economy has been faced with.

But it is not “true” that the US government is at all “dependent on financial markets to pay its bills”. The exact opposite is the truth. It might be the case that certain accounting procedures are rehearsed by the US Treasury and the Federal Reserve bank before the former spends US dollars. These voluntary constraints – shunting cash from bond sales into a particular account that is then debited when government spending occurs – are just a chimera.

The intrinsic financial capacity of the US government is clear – it issues the currency. So it could bring in a rule that said that all Treasury officials had to run a lap of some park in Washington D.C. before each spending transaction was formalised. That would be commensurate with all the other constraints (hoops) it chooses to jump through.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? February – for more discussion on this point.

So the US government is not dependent on the financial markets. The latter are dependent on the government spending!

Lawrence Goodman then rehearsed the “foreigners will stop buying angle”:

But in recent years foreigners and the U.S. private sector have grown less willing to fund the U.S. government.

So what! See the analysis of this scare tactic above.

He then concludes that:

The Fed is in effect subsidizing U.S. government spending and borrowing via expansion of its balance sheet and massive purchases of Treasury bonds. This keeps Treasury interest rates abnormally low, camouflaging the true size of the budget deficit. Similarly, the Fed is providing preferential credit to the U.S. government and covering a rapidly widening gap between Treasury’s need to borrow and a more limited willingness among market participants to supply Treasury with credit.

It is hard to know where to start with this argument so late in the afternoon.

First, the true size of the budget deficit is not camouflaged at all. We know virtually to the cent what it is at regular intervals. But we also know that it is far too small relative to GDP because the unemployment queues are long and hardly shrinking.

Second, the idea that “preferential credit” is being provided implies that the private sector is being starved of credit. That is patently false. The private banks could expand credit as fast as there were credit-worthy borrowers walking through their door. The US Federal Reserve would then always stand by ready to provide the reserves necessary to maintain stability in the payments system should the private banks not attract the necessary funds from other sources.

Third, it is entirely sensible that the US government stop providing corporate welfare to the private bond markets in the form of guaranteed annuities (treasury bonds). Issuing debt to the private bond markets generates no public purpose and should be stopped.

The closing argument by Goodman tops the lot! He introduces the Euro crisis and hints that the US is likely to follow suit:

The failure by officials to normalize conditions in the U.S. Treasury market and curtail ballooning deficits puts the U.S. economy and markets at risk for a sharp correction. Lessons from the recent European sovereign-debt crisis and past emerging-market financial crises illustrate how it is often the asynchronous adjustment between budget borrowing requirements and the market’s appetite to fund deficits that triggers a shock or crisis. In other words, budget deficits often take years to build or reduce, while financial markets react rapidly and often unexpectedly to deficit spending and debt.

There are no lessons from Europe for the US. The monetary systems are different – the former involves government issuing debt in a foreign currecy (the Euro) while the latter has the currency-issuing US government at the centre.

It demonstrates appalling ignorance or deception to conflate the two systems and draw conclusions from the EMU about the US.

For example, Greece can go bankrupt – by which we mean would be unable to pays its bills in Euros – because it effectively uses a foreign currency and cannot instruct “its” central bank to provide adequate funds. It actually doesn’t have a central bank anymore given that the Greek central bank is part of the European Central Bank system.

The recent default by the Greek government demonstrates its solvency risk.

The US government can never become bankrupt. Last year, the former US Federal Reserve Governor Alan Greenspan told CNBC that:

The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So there is zero probability of default.

The way the mainstream economists have pushed this capacity under the carpet is via the hyperinflation myth. They have effectively been able to pressure governments into borrowing (back their own spending) from private markets to “fund” its spending when they know clearly that such an act is totally unnecessary.

There was an interesting PBS News Hour program a few years ago (October 7, 2008) as the US Federal Reserve was about to introduce its Quantitative Easing program for the first time. The program – Federal Reserve Employs Tools to Ease Credit Fears – interviewed economist Alan Blinder, a former vice chairman of the Board of Governors of the US Federal Reserve. Here is a snippet of the transcript after being asked to explain how the US Federal Reserve gets “money into the system”:

Well, when the Fed first starts these operations, including the other ones they do, what they try to do is re-jigger their balance sheets, sell one asset, and that for the Fed has been mostly been treasuries, and buy something else.

As that capacity gets used up, the Fed can no longer swap one asset for another. And then it has to … we use the euphemism “print money.” What that really means is somebody is on a keyboard creating electronic images of money. Large amounts of money are not cash.

So these are credits at the Federal Reserve system basically. A central bank can do that; a commercial bank cannot do that.

That couldn’t be clearer.

The point here though is that the central bank acts as “part” of the overall US government (consolidated treasury-central bank) and can credit bank accounts at will. Please read my blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank – for more discussion on this point.

Think about what a US dollar is. Anyone holding one can present them (or the electronic version – deposits) to the US government in return for a tax credit (payment of their tax liabilities). So when the Federal Reserve credits bank accounts it is really providing Treasury tax credits to the holders of those accounts.

When a US citizen (this applies in any sovereign nation) pays their taxes the conceptual chain of events is that the central bank accounts for the payment (acknowledging the tax credit) and informs the Treasury that the tax obligation has been eliminated. The dollars don’t go anywhere! The scores are adjusted – that is it. So the central bank crediting behaviour creates assets in the non-government sector which sit in reserves held by the member banks.

The conclusion is obvious as it is powerful. These electronic credits come from nowhere and enter the non-government sector as a tax credit against obligations that the non-government agents have to government. The source of these funds cannot come from the taxpayer. Similarly, when the tax credits are redeemed they go nowhere other than into accounting books to record the events.

Effectively, the government is owing itself through a sequence of elaborate accounting tricks.

Now the build-up of public debt on the US central bank balance sheet arose from its Quantitative Easing program which was conducted on the false premise that the private banks were not lending because they didn’t have enough reserves. Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

The reality is that it did nothing much – an asset swap – but denied the non-government sector of income as a result of the public debt being purchased by the US Federal Reserve. So the demand effects could have been, in fact, negative. It will be hard to determine that empirically.

But once the “damage” is done, the fact remains that the consolidated US governments holds 11 per cent of its own debt within the US Federal Reserve and more in other areas of the public sector (Social Security etc). None of those assets are necessary for anything given that the US government issues

the currency and does not need to “save” before it can spend.

Some would respond by saying that the Federal Reserve provides interest earnings to the Treasury and that the writing off of the assets from the central bank’s balance sheet would further squeeze the US government of revenue. Of-course, there is no sense to that statement once we understand the US government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. So the “interest payments” are an accounting ploy which do not enhance the capacity of the government to spend.

That is in contradistinction to interest payments from government to non-government holders of public debt. They add to income and enhance the capacity of the holders to spend.

What would happen if the US Federal Reserve did write off all the public debt holdings? Would they go broke? Hardly. Please read my blog – The US Federal Reserve is on the brink of insolvency (not!) – for more discussion on this point. The US central bank and hence the US government cannot go broke.

Conclusion

As a proponent of MMT, I do not consider there to be a public debt problem in the US so the analysis presented here is rather moot.

However, what it shows is that even within the voluntarily-constrained system that regulates the relationship between the US treasury and the central bank, the latter can still effectively buy as much US government debt as it likes.

That is enough for today!

“They concluded that if the foreign holdings fell by $US100 billion in a month (about a 2 per cent decline – which would be a major shift by historical standards) then the yields on 5-year bonds would rise in the long-run by “about 20 basis points”.”

Is that swapping cash/other currency instruments with domestic holders or by reduction in funding the trade deficit?

What’s the alternative holding?

“The reality is that it did nothing much – an asset swap – but denied the non-government sector of income as a result of the public debt being purchased by the US Federal Reserve.”

Was the swap not undertaken voluntarily by the private sector, and if so, would they not have done it unless they were making a profit on the transaction? Is the private sector really in a worse position as the statement above seems to imply?

@Larry,

“Was the swap not undertaken voluntarily by the private sector,”

Many (perhaps most) of the USTs went right from the auctions to the Primary Dealers of US Treasury Securities to the Fed, so the true ‘private’ sector never was involved (it’s a ‘Dealer’ market). As far as deprived income, I believe Bill is referring to the fact that the non-govt sector will be deprived of interest income from the UST securities since the Fed stepped in front of them…. resp,

“Was the swap not undertaken voluntarily by the private sector”

Think the transaction through. It’s not the seller that matters – they were going to sell anyway.

By definition the Fed outbid somebody for that UST. So it is the person outbid (transitively) that is denied access to the UST income and must remain in reserves. And it is that transitive outbidding that flattens the yield curve.

Was the swap not undertaken voluntarily by the private sector, and if so, would they not have done it unless they were making a profit on the transaction? Is the private sector really in a worse position as the statement above seems to imply?

Since the purchases are voluntary, it is hard to argue that they are in a worse position. They receive immediate liquidity, somewhat in excess of the purchase price of the bonds they sold, in exchange for foregoing a somewhat higher dollar payment later in the future. Quick immediate term profits on the bond investment are substituted for larger longer term profits.

But I think the point is that we are talking about marginal amounts, so as Bill says the purchase don’t do much. The private sector ends up receiving less from the government than it was going to receive, but what it receives, it receives faster.

“The intrinsic financial capacity of the US government is clear – it issues the currency.”

Well, maybe it would if it could, but it can’t, so it won’t.

Issue the currency that is.

I think it would be more accurate to say that the intrinsic financial capacity of the US government is clear – it has virtually none. The government has parlayed its Constitutionally-found issuance authority out to the private corporations who actually run the country.

Bu that would require acknowledgement that the Federal Reserve is a private corporation that is owned by the private regional Federal Reserve Banks, the members of which actually “issue” the US currency, or the things that serve as measures of the money supply, in the form of private bank credit.

Unless of course by using the term ‘US currency’ what you mean is not the money supply of the US that drives the economy, however measured, but merely the actually paper notes and coins that make up the ‘currency’ portion of the M1 money supply.

In which case it would still be correct to say that the private Federal Reserve corporation issues the currency, as 99 percent of the ‘paper and coin’ currency in this country is, via double-entry accounting, ‘issued into existence’ by the Federal Reserve Banks, after it is received by the Federal Reserve in return for its payment for the paper on which the money is printed.

So what?

Who cares?

“Which side of the deal got the better outcome? It depends on whether you value real goods and services or bits of paper more!”

I generally agree with MMT regarding sovereign money, but statements like this always strike me as odd. Why would China value bits of paper over real goods and services? Are they insane? Are they selfless or generous, wanting to give the US the fruits of their labor? I think there’s a lot more going on here.

For example, China’s massive exports to the US and other countries drive a fair amount of its industrial development and expansion. It’s not just taking bits of paper, its using a massive export market to grow and has been actively engaged in maintaining that export market at great expense by pegging the Yuan to the dollar and keeping its labor cheap. I think China is forgoing the domestic use of a decent fraction of its economic output to keep standards of living lower, keep labor costs down, and therefore keep costs down so that it can export to large, developed markets. In doing so, it is developing its own markets and industrial strength.

At the same time, the US has been importing these Chinese products but not building and developing them for itself. This means that the US has become dependent on China for many of its material needs. It sounds nice to say that we get real goods and resources in exchange for paper, but it’s not true. We’re actually using our paper to get cheaper goods overseas and also to avoid developing or growing our own industries to develop those same goods. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with this–everyone can’t make everything everywhere! But the exchange is definitely not “real stuff for bits of paper.”

I hope I’m not being unfair here, but your argument sounds like the following metaphor between a fisherman and his customer. The fisherman has all the reels and rods, the boat, and the expertise. The customer has the paper money to buy his fish. “Ha!” thinks the customer, “I’m just giving the fisherman bits of paper and he gives me whole fish. I’m clearly getting the better deal.” Meanwhile, the fisherman uses those bits of paper to buy a better boat, hires an assistant to figure out ways to increase yield, etc. Even if you forget about the paper, in this situation the fisherman is actually fishing and being productive, while the customer is simply consuming. If the fisherman retires, the customer will have to go looking for a new source of fish or start fishing on his own–from scratch, without the fisherman’s expertise or abilities.

And I think the story is even more complicated than anything I wrote above.

“I generally agree with MMT regarding sovereign money, but statements like this always strike me as odd. Why would China value bits of paper over real goods and services? Are they insane? Are they selfless or generous, wanting to give the US the fruits of their labor? I think there’s a lot more going on here.”

The Chinese government maintain domestic peace by keeping people employed. And they have a lot of people!

I enjoyed Bolo’s comments as well as Dismayed’s. I’ve heard both Randy Wray and Bill make the comment about receiving real goods for paper and while it makes sense on the surface, it just has never set well with me. As you both mention, in addition to those pieces of paper, China also gets higher employment and the ability to expand it’s industry. Not all of those additional products are exported and so China gets the added benefit of expanding domestic output as well. I don’t agree with a lot of their labor policies, but the fact remains that someone who works 10 to 12 hours a day in a factory at low pay is probably a lot less likely to be doing something the Chinese government doesn’t like than someone who is unemployed. Now that I type that up, it sounds an awful lot like a pseudo-implementation of a Job Guarantee albeit with lower benefits and worse working conditions than an MMT JG.

” “Ha!” thinks the customer, “I’m just giving the fisherman bits of paper and he gives me whole fish. I’m clearly getting the better deal.” ”

But the customer must produce something first to obtain the bits of paper.Bits of paper are simply reflecting the customer’s product (unless he borrowed the money from the bank).Its effectively as if the customer trades his production for the fisherman’s production.In contrast,MMT advocates that the gvt doesnt need to produce in order to obtain the bits of paper so the example doesnt apply to a gvt.

But the idea that US is giving China worthless bits of paper in exchange for China’s production is a little confusing for me too.I think thats not the exact truth.Since its (mostly) the private US sector that imports from China ,this means the private sector must be productive in order to obtain the money for the imports.The thing is that the gvt has the ability to “replace” the “lost money” ie finance the trade deficit without having to produce anything,since it can issue money at will.

To be picky, “nearly infinite” is a logical impossibility. Anything that isn’t actually infinite, no matter how big the number, is no closer to being infinite than the number 1 is. Name a number as big as you like, it is still infinitely smaller than infinity.

Protestant ethic capitalism benefits the many, self-loving, animal spirit capitalism benefits the few. Moral vs amoral, where wealth preservation dominates the media much like the discussions of the bullionists. So much transferred wealth and no place to hide. Hoarded wealth that is the deficit, where velocity equals zero. Can there be too much money when power and influence are for sale?

bill, many thanks for your insights. There was speculation recently that the british government could simply cancel the bonds that the bank of england holds. here is the link http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/40e269bc-69e2-11e1-8996-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1qWAT2ros. do you agree with the views in this article? an economist opined in a meeting with my firm that they wouldn’t do that as its operationally impossible. Also, cancelling debt would be sending the wrong signal to the market and the effectivness of QE. any thoughts of yours would be highly appreciated.

@Crossover:

“But the customer must produce something first to obtain the bits of paper.Bits of paper are simply reflecting the customer’s product (unless he borrowed the money from the bank).Its effectively as if the customer trades his production for the fisherman’s production.In contrast,MMT advocates that the gvt doesnt need to produce in order to obtain the bits of paper so the example doesnt apply to a gvt.”

Actually, I think my metaphor applies even better for governments rather than the individuals that I used–I was just trying to humanize it. I didn’t specify where the customer got the bits of paper, so he may as well just be printing them himself. The fisherman and others accept those bits of paper as payment for goods and services. As far as I can tell this is in line with MMT, if you pretend the two parties involved are currency-sovereign governments or a single currency-sovereign govt (the customer) buying the products of a private sector actor (the fisherman).

The funny thing is that MMT argues that “government doesn’t need to produce in order to obtain the bits of paper,” which is true. But government has to ensure that others will accept its currency. I see this as being accomplished in two ways:

(1) Inside the boundaries of a given sovereignty, the government imposes taxes to be paid only in the sovereign’s currency. There are two ways to do this–(a) in the case of a hierarchical power structure, tell people to pay or “face the consequences” or (b) in the case of a more egalitarian or distributed power structure, have a more general social contract among equals that everyone pays their fair share in the agreed upon currency.

(2) Outside the boundaries of the given sovereignty, other sovereigns will accept the sovereign currency as an acknowledgement that they are (relative) equals. States recognize the sovereignty of other states–kind of getting into the “anarchy among states” area of thinking. In fact, this scenario gets quite complicated with a variety of motives for accepting the paper money–including, for example, the relationship between the US and China that I gave in my original comment above.

Recasting the metaphor, if the customer is actually a government and the fisherman is a private citizen under that government, then the customer either has a big gun (scenario 1a) or is part of a very flat power structure that has directed spending in this direction (and maybe has a very small gun…) (scenario 1b). If both participants are governments (scenario 2), then the fisherman may take the paper money for a variety of reasons including that he uses it to upgrade his own abilities, he values something else the customer does for him, global cultural norms dictate he must treat the customer’s money as valid, etc.

I think there’s more to this as well, but this comment is getting kind of long… 🙂

There is a lot here about which I am interested in learning. Some questions:

If China decided to spend its dollars would that cause inflation (and employment in the the US) — is that a problem?

If China decided to spend its dollars on productive assets — is that a problem for the average US citizen (politically that seems to be blocked most of the time)?

China’s trade surplus and purchase of government securities always seem to be connected. Are they? Is it the trade surplus that forces the Federal Government into a deficit?

Don’t a lot of ordinary citizens want to hold US Treasuries? Wouldn’t ending this not affect just rich bond traders? If the Treasury stopped issuing securities, so reserves have nowhere to go, would that not drive short-term rates to zero? Is that a problem?

Finally I agree completely with Bolo that the idea of trading real goods for ‘paper’ is all to the good for us is incorrect. There are people (R. Wray seems to be one) that feel manufacturing has no real worth. That may be the impression from someone who has spent their life in academia, but it is dead wrong. I’m a scientist and I can tell you that as manufacturing goes, the R&D that it supports also goes, although this can take a while. It is happening now and it is not a good thing for the United States.

A side comment: There are a lot of issues in China but one reason that I think they will keep rolling along is that the leadership seems to place a high priority on keeping everyone working. I think Keynes once said something like, keep everyone employed and the rest will take care of itself … which seems to be a part of MMT as well.

“The point is that the US dollars earned by the Chinese as exporters were sitting in US bank accounts and the holders of the deposits decided to convert them into interest-earning assets by buying bonds. One US-dollar bank account was reduced (as the withdrawals to pay for the bonds occurred) and another US-dollar bank account (at the Federal Reserve) was opened – the payment for the bonds.”

A certain percentage of the dollars earned by Chinese exporters must be converted into Chinese currency in order to profit from all of those exports. I mean, factories have to be built, employees paid, owners become wealthy, etc. So those exchange rate transactions should drive up the value of the yuan, but in order to maintain the currency peg the Chinese government counters by buying dollars (Treasuries). Right?

Isn’t there, in principle, a size of debt at which the annual interest payments constitute a net addition of financial assets to the economy which is potentially problematic?

I mean, governments have a few tools for managing the money supply and striking the right balance between employment and inflation: taxing and “borrowing” versus spending. At some stage, if the debt becomes large enough, then the net additions of money to the economy which arise from interest payments on the debt, may leave little room for a government to manouvure. The desired spending plus non-discretionary interest payments may add more to the economy than acceptable levels of taxing can remove, thus leading to inflation. Of course, the government could always “borrow” more to serve this purpose, but what if no-one wants to buy the debt?

If the above makes any sense, then it seems to me that, even under MMT, large government debts might be problematic and a ceiling desirable. Problematic in the sense of reducing the options/policy space of the government to manage the economy adequately. Where the line is drawn I have no idea.