The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The ECB is a major reason the Euro crisis is deepening

I notice that a speech made yesterday (November 8, 2011) in Berlin – Managing macroprudential and monetary policy – a challenge for central banks – by the President of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann has excited the conservatives and revved them back into hyperinflationary mode. The problem is that the content that excited them the most is the familiar mainstream textbook obsession with budget deficits and inflation (through the even more obsessed German-lens). That means it is buttressed with misinformation about how monetary operations that accompany deficits actually work. It tells me that the European Central Bank which is the only institution in Europe that has the capacity to end the crisis is in fact a major reason the crisis is deepening.

The Speech was given to “The ESRB at 1” Conference which was jointly hosted by the SUERF, Deutsche Bundesbank, IMFS.

SUERF is the “The European Money and Finance Forum” and claims it “the pre-eminent independent non-profit European association designed to create an active network between professional economists, financial practitioners, central bankers and academics for the analysis and mutual understanding of monetary and financial issues”. It fails in that mission if this conference is anything to go by.

The Institute for Monetary and Financial Stability is a German university research centre that is funded from a public foundation that was established in 2002 when One Deutsche Mark gold coins were sold to commemorate the D-Mark when Germany swapped to the Euro. The foundation is obsessed with price stability.

As an aside, the ESRB also stands for The Entertainment Software Rating Board which is “a non-profit, self-regulatory body established in 1994 by the Entertainment Software Association (ESA)” which “assigns computer and video game content ratings, enforces industry-adopted advertising guidelines and helps ensure responsible online privacy practices for the interactive entertainment software industry”.

Perhaps the ESRB should have rated the “ESRB at 1” Conference – the content of some of the presentations seemed consistent with a “fantasy game”.

The Speech received some press coverage overnight – for example, Bloomberg carried the headline Weidmann Says ECB Can’t Print Money to Finance Public Debt – which is patently false.

The Bloomberg article said:

European Central Bank council member Jens Weidmann said the ECB cannot bail out governments by printing money.

The fact is that they are already doing that by making secondary bond market purchases of bonds from governments which the bond markets will not lend to at reasonable rates at present.

The ECB call this the Securities Market Programme (SMP) which was established on May 14, 2010.

Article 1 of the ECB Decision says:

Under the terms of this Decision, Eurosystem central banks may purchase the following: (a) on the secondary market, eligible marketable debt instruments issued by the central governments or public entities of the Member States whose currency is the euro; and (b) on the primary and secondary markets, eligible marketable debt instruments issued by private entities incorporated in the euro area.

You can read more recent information about the programme HERE.

As of November 4, 2011 the ECB has bought 183,019 million euros worth of bonds under the programme.

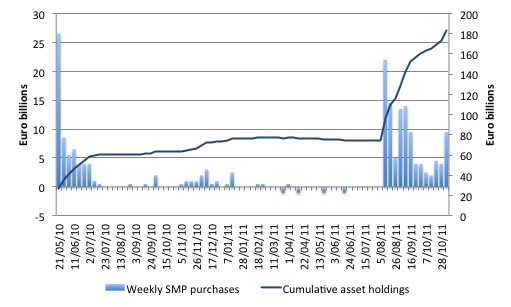

The following graph shows the history of the SMP since May 2010 (up to the most weekly statement from ECB – November 4, 2011). The bars shows the weekly purchases (or redemptions) while the blue line shows the cumulative asset holdings associated with the program (now at 183 billion Euros).

Clearly they accelerated at times when the private bond markets were withdrawing from tenders (as evidenced by the widening spreads of member state bonds against the bund). The SMP is unambiguously a fiscal bailout package which amounts to the central bank ensuring that governments can continue to function (albeit under the strain of austerity) rather than collapse into insolvency.

You can also learn about the “sterilising” functions associated with the SMP from HERE (go to the Ad-hoc communications tab on the page).

For example on November 7, 2011, the ECB announced the following “fine-tuning operation”:

As announced by the Governing Council on 10 May 2010, the ECB conducts specific operations in order to re-absorb the liquidity injected through the Securities Markets Programme (SMP). In this regard, the ECB will carry out a quick tender on 8 November at 11.30 in order to collect one-week fixed-term deposits with settlement day on 9 November. A variable rate tender with a maximum bid rate of 1.25% will be applied and the ECB intends to absorb an amount of EUR 183 billion. The latter corresponds to the size of the SMP, taking into account transactions with settlement on or before Friday 4 November, rounded to the nearest half billion. As the SMP transactions which settled last week were of a volume of EUR 9,520 million, the rounded settled amount – and the intended amount for absorption accordingly – increased to EUR 183 billion. The benchmark allotment amount in MROs takes into account the liquidity effect of non-standard measures, assuming an unchanged size of the SMP and full sterilisation of this amount via the above mentioned liquidity-absorbing operation. Fixed term deposits held with the Eurosystem are eligible as collateral for the Eurosystem’s credit operations. The ECB intends to carry out another liquidity-absorbing operation next week.

What does that all mean? Answer: the Greek government issues bonds to the private market who knows they can sell them to the ECB and thus eliminate any carry risk. The ECB buys the bonds in the secondary market (that is, after they have been issued by the Greek government in the primary tender market) with euros which it creates.

They then propose a tender to offer deposits with the ECB (with a ceiling of 1.25 per cent yield) up to the volume of outstanding SMP bond purchases. So they swap the euros for an interest earning account with the ECB instead of leaving the interest-earning bond in the hands of the private sector.

This swap is referred to as the sterilisation operation and allegedly “neutralizes” the bond purchases “by draining the same amount of money from the banking system”.

Do you smell a rat?

In a speech on October 21, 2011, a member of the Executive Board of the ECB (José Manuel González-Páramo) – The ECB’s monetary policy during the crisis said in relation to the SMP that:

The main purpose of this programme is maintaining a functioning monetary policy transmission mechanism by promoting the functioning of certain key government and private bond segments … The SMP should, of course, be clearly distinguished from the policy of quantitative easing. While the objective of the SMP is to repair the transmission mechanism, quantitative easing aims at injecting additional central bank liquidity in order to stimulate the economy. As a result, quantitative easing, as for instance with the Bank of England, comes with precise quantitative targets. By contrast, the size of SMP purchases is driven by an intervention strategy which seeks to improve market functioning. Let me stress that the liquidity injected through SMP purchases is re-absorbed on a weekly basis so as to specifically neutralise the programme’s liquidity impact.

So you can see they continue to peddle the myth that QE is about giving banks more money to lend. The fallacy in that logic is that bank lending has not be constrained by a lack of reserves. Rather there has been a dearth of credit-worthy customers at a time when banks have tightened their lending criteria given the financial uncertainty.

Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

Quantitative easing is an asset swap designed to bid up the prices of assets in certain maturity ranges and thus keep interest rates in those segments lower. The only way it would have helped alleviate the crisis is if the lower rates stimulated investment growth. However, with the crisis so deep and consumers bunkering down for fear of unemployment and insolvency (given the debt overhang), firms have been able to satisfy demand with existing capacity.

Further, the fact that most central banks have been offering a return on excess bank reserves means that the SMP is virtually indistinguishable.

Both keep yields lower than otherwise by strengthening demand in the bond markets and both provide an interest-bearing alternative to the bond-holders.

The reality is that the ECB is bailing out governments by buying their debt and taking the risk of default off the private sector.

The neutralising of the SMP purchases is another trick that plays on misunderstandings of what is going on. I will come back to that later when I consider the Jens Weidmann speech.

But the SMP demonstrates that the ECB is caught in a bind. It repeatedly claims it is not responsible for resolving the crisis but realises that it is the only institution in the monetary system that has the capacity to resolve it – given it issues the currency.

More recently, José Manuel González-Páramo) gave a speech in Spain (November 4, 2011) – The ECB and the sovereign debt crisis where he claimed the ECB has “no responsibility” for resolving the crisis.

Commenting on the agreements reached on October 26, 2011 (which have been overrun by further developments – including two governments falling – since), he said:

As the ECB has repeatedly stressed, the main responsibility for resolving this crisis lies with governments and the financial sector. Euro area governments’ unwillingness to adapt their fiscal and competitiveness policies to the requirements of EMU very much lies at the heart of the current “sovereign debt crisis”. Excessive risk-taking by an over-leveraged and inadequately regulated financial sector is, of course, the other source of the present “financial turmoil”.

A reader might be forgiven for adding – “and the lack of a system-wide fiscal authority and the bloody-minded austerity mindset of the central bank …”.

As this crisis drags on and morphs into increasingly bizarre outcomes, it is clear the one of the central culprits is the ECB itself. It alone has the currency-issuing capacity to provide sufficient demand to allow the region to grow again.

The crisis is about a lack of growth. The bond markets would not be attacking governments – one by one – if their economies were growing and unemployment was low and tax revenues were high.

The crisis is not about the particular policies of the member states. José Manuel González-Páramo claimed that “the true ‘failures’ leading up to the current sovereign debt crisis lie with the unsustainable fiscal and structural policies pursued by many of these governments before the crisis and with the governance system of the euro area.”

It is clear that there were “unsustainable structural policies” pursued by governments – deregulation of the financial sector, not enough regulative oversight of real estate markets (including allowing private citizens to fund mortgages in foreign currencies), a bias towards budget austerity (under the Stability and Growth Pact) which meant that growth had to rely largely on private credit expansion – etc.

This behaviour of governments leading up to the crisis was based on exactly the same logic that is driving the fiscal austerity. That free markets are best and government should have as small a footprint as possible.

The neo-liberal policy positions that governments adopted and the conservative design of the European Monetary Union were directly responsible for making the Eurozone highly vulnerable to perturbations in aggregate demand.

When the Eurozone experienced the large and rapid negative demand shock in late 2007 it was obvious that a rapid response from the currency-issuer was required to prevent the bond markets from raising the alarm bells as the automatic stabilisers (tax revenue collapse) drove the budget deficits up.

The fact that the ECB – as part of the destructive Troika – chose to inflict a negative growth strategy on the region – by forcing fiscal austerity onto the weakest economies guaranteed that the problem would morph into a full-blown crisis.

The fault lies squarely with the Weimar-obsessed ECB. The leading officials should resign en masse and hand over the “fiscal authority” to those who know how to make economies grow.

Which brings me to the Jens Wiedmann speech in Berlin yesterday (November 8, 2011).

I won’t analyse the whole speech due to time constraints. Rather I will focus on some fundamental macroeconomic propositions which also tie into the previous discussion about the SMP and quantitative easing.

In the latter part of the speech he discussed the “Challenges from the sovereign debt crisis”. He noted that a huge risk for central banks in a crisis is that there might be pressure for “burden shifting from fiscal to monetary policy, and the ultimately necessary political action to address the root cause of the crisis might be delayed, incomplete, or not happening at all”.

What does that mean?

His elaboration was pure mainstream textbook stuff:

One of the severest forms of monetary policy being roped in for fiscal purposes is monetary financing, in colloquial terms also known as the financing of public debt via the money printing press. In conjunction with central banks’ independence, the prohibition of monetary financing, which is set forth in Article 123 of the EU Treaty, is one of the most important achievements in central banking. Specifically for Germany, it is also a key lesson from the experience of the hyperinflation after World War I. This prohibition takes account of the fact that governments may have a short-sighted incentive to use monetary policy to finance public debt, despite the substantial risk it entails. It undermines the incentives for sound public finances, creates appetite for ever more of that sweet poison and harms the credibility of the central bank in its quest for price stability.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) the legislative ” prohibition of monetary financing” in the EU Treaty is a victory for ignorance and conservatism – a deliberate strategy to hamper public purpose and one of the reasons the EMU is in such a mess right now.

It is one of the “most important achievements” of the neo-liberal period that has hamstrung the capacity of our governments to respond to crises that they alone have the ability to resolve.

It is tied in with the myth of central bank independence.

Please read my blogs – Central bank independence – another faux agenda and The consolidated government – treasury and central bank – for more discussion on this point.

It is clear that German economists (in the main) and economic policy makers have become locked in a time warp that centres on the 1920s. For a more modern perspective, please read my blog – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 – for more discussion on why the hyperinflation fear has to be tempered in a historical understanding.

The most pure operation for a government is to net spend without issuing any public debt. While public debt is a form of private wealth and provides private income (which is why QE has probably been deflationary – withdrawing the income flow from the private sector as the central bank hands it over to the treasury) it is largely used as a form of corporate welfare.

Please read my blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – for more discussion on this point.

Under the convertible currency system (Bretton Woods) governments had financial constraints on their spending because of the need to maintain fixed exchange rates. So bond issues (which transferred purchasing power from the private to the public sector) were necessary if the government chose to run a budget deficit (spending greater than taxation).

Please read my blog – Gold standard and fixed exchange rates – myths that still prevail – for more discussion on this point.

That system lapsed in 1971 (although different countries abandoned the peg at different times after that). Under a fiat currency system there is no need at all to issue debt.

A national government in a fiat monetary system has specific capacities relating to the conduct of the sovereign currency. It is the only body that can issue this currency. It is a monopoly issuer, which means that the government can never be revenue-constrained in a technical sense (voluntary constraints ignored). This means it can spend whenever it wants to and has no imperative to seeks funds to facilitate the spending.

This is in sharp contradistinction with a household (generalising to any non-government entity) which uses the currency of issue. Households have to fund every dollar they spend either by earning income, running down saving, and/or borrowing.

Clearly, a household cannot spend more than its revenue indefinitely because it would imply total asset liquidation then continuously increasing debt. A household cannot sustain permanently increasing debt. So the budget choices facing a household are limited and prevent permament deficits.

These household dynamics and constraints can never apply intrinsically to a sovereign government in a fiat monetary system.

A sovereign government does not need to save to spend – in fact, the concept of the currency issuer saving in the currency that it issues is nonsensical.

A sovereign government can sustain deficits indefinitely without destabilising itself or the economy and without establishing conditions which will ultimately undermine the aspiration to achieve public purpose.

A government operating in a fiat monetary system, may adopt, voluntary restraints that allow it to replicate the operations of a government during a gold standard. These constraints may include issuing public debt $-for-$ everytime they spend beyond taxation. They may include setting particular ceilings relating to deficit size; limiting the real growth in government spending over some finite time period; constructing policy to target a fixed or unchanging share of taxation in GDP; placing a ceiling on how much public debt can be outstanding; targetting some particular public debt to GDP ratio.

All these restraints are gold standard type concepts and applied to governments who were revenue-constrained. They have no intrinsic applicability to a sovereign government operating in a fiat monetary system. So while it doesn’t make any sense for a government to put itself in a strait-jacket which typically amounts to it failing to achieve high employment levels, the fact remains that a government can do it.

In general, the imposition of these voluntary restraints reflect ideological imperatives which typically reflect a disdain for public endeavour and a desire to maintain high unemployment to reduce the capacity of workers to enjoy their fair share of national production (income).

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability does not include any recognition of the legitimacy of these voluntary restraints. These constraints have no application to a fiscally sustainable outcome. They essentially deny the responsibilities of a national government to ensure public purpose, as discussed above, is achieved.

The “prohibition of monetary financing” noted by Weidmann is in the category of these ideologically-driven voluntary restraints. They are dysfunctional because they limit the scope of governments to pursue public purpose.

He noted that governments “may have a short-sighted incentive to use monetary policy to finance public debt, despite the substantial risk it entails. It undermines the incentives for sound public finances, creates appetite for ever more of that sweet poison and harms the credibility of the central bank in its quest for price stability”

Elected governments are our expression of democracy. It is in preference to totalitarian states where all the major decisions that impact on our lives are made by unelected and unaccountable officials who have gained their positions because they are part of the elite.

The reality is that during the neo-liberal period – proponents of this ideology continually talk about the benefits of individual freedom and transparency and accountability yet create policy structures – for example, “independent” central banks and fiscal commissions – which reduce the democratic rights of the citizens.

Clearly, governments can be seduced by lobby groups – we have the perfect case of that in the way that Wall Street governs the US. Governments can make terrible decisions and cause economic mayhem. The decision to deregulate financial markets, for example, is the case in point.

But as long as citizens can form parties and vote such governments have limited tenure. We are unable to vote for and throw out unelected central bank officials. So I do not think it is very sophisticated to deliberately constrain our elected governments from acting in our best interests just because they might make mistakes and get captured by some lobby group or another.

Also note the terminology “substantial risk”. Risk is not an absolute – determinate concept. The risk he is talking about is inflation. And he is correct to highlight that the principle risk of using fiscal policy in an inappropriate manner is inflation.

I would generalise – the major risk associated with spending per se – public or private – is inflation. It can be substantial, depending on the state of the economy. At times, the risk will be low to close to zero. Other times higher.

But that risk is associated with the spending not the “monetary” operations that might accompany the spending (for example, bond issues or not).

Jens Weidmann said:

A combination of the subsequent expansion in money supply and raised inflation expectations will ultimately translate into higher inflation.

This is not a factual statement that has historical precedence despite his earlier appeal to German experience during the Wiemar years.

The correct statement is that an expansion in the money supply may raise inflation expectations and may translate into higher inflation. It all depends.

To gain an understanding of the inflationary process – please read the following blogs – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1 and Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 2.

You will learn that inflation is the continuous rise in the price level. That is, the price level has to be rising each period that you observe it. So if the price level or a wage level rises by 10 per cent every month, then you have an inflationary episode. In this case, the inflation rate would be considered stable – a constant rise per period.

If there is a once-off price rise (say a VAT increase) and all other prices adjust, that would not constitute inflation. So a price rise can become inflation but is not necessarily inflation. Many commentators and economists get this basic understanding wrong.

Business firms are basically “quantity adjusters” if they have spare capacity. They will seek to maintain market share when nominal demand grows by increasing output where possible. Should nominal demand growth (supported in part by net public spending) outstrip this capacity then firms will then employ the only adjustment they have left – they become price adjusters – because they can no longer expand real output.

Bottlenecks in some sub-markets may occur before other sectors are at full capacity and so price pressures might emerge just before overall full capacity is reached. So, in reality, the aggregate supply response (which tells you how much real output will be forthcoming at each price level) may not be strictly reverse-L shaped (where price is on the vertical axis and output on the horizontal axis). The extent to which the reverse-L becomes a curve at at a point approaching full capacity is an empirical matter.

The point is that inflation occurs when there is chronic excess demand relative to the real capacity of the economy to produce.

Say we start from a full employment point and the non-government sector desires to save 5 per cent of GDP overall and sets about doing that. The government would have to run deficits equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP (or close to it) to ensure that nominal spending was sufficient to absorb the productive capacity and maintain full employment.

It could maintain that spending commitment forever (assuming the non-government sector didn’t change its aspirations) and continuously achieve full employment without inflation.

If there was a major collapse in productive capacity (say, because a nation lost a key productive region as a result of some war settlement) then nominal spending would have to fall in line with the loss of real output capacity. All spending would be “inflationary” in that situation and the government would have to make political decisions as to how much private and public spending was cut.

Clearly in that sort of extreme situation (for example, the situation the resettlement in Zimbabwe caused) it is hard to avoid accelerating inflation because it is difficult to cut essential services and/or private consumption by significant amounts. The political problem of rising unemployment militates (or it used to) against drastic spending cuts and/or tax rises (to force private spending cuts).

But in more normal times when productive capacity grows with investment and the labour force grows with population change, nominal spending can grow without causing inflation.

There is no inevitability at all.

Now what about the claim that deficits would have to be “financed” by bond sales to avoid them becoming inflationary? Quite simply it is ideological dogma and reflects a willingness to either not understand how the monetary system operates or a deliberate desire to mis-inform readers and/or listeners so that a paradigm of public austerity can be justified.

The point of Jens Weidmann’s assertions is that he wants to absolve the ECB from any responsibility in perpetuating the crisis.

In understanding inflation then we have to focus on the spending side. Spending creates demand for goods and services and firms respond to that – either by selling real goods and services (if they have capacity to produce them spare) or by rationing the excess nominal spending via price rises.

However, the mainstream macroeconomic textbooks construct this in a totally different (and erroneous) way (and that misconstrual is evident in Weidmann’s exhortations against “monetisation”).

These textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters introduce the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The writer fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

The textbook argument claims that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

What would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made.

Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target.

Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance.

So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. As noted above, all components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk.

The following blogs might be of interest here – Why history matters and Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary and The complacent students sit and listen to some of that.

Jens Weidmann raises another interesting point though:

In a monetary union of independent countries, one additional aspect that is often missed in the current discussion is particularly relevant. Monetary financing in a monetary union leads to a collectivisation of sovereign risks among the tax payers in the monetary union. It is equivalent to issuing Eurobonds. However, the redistribution of such risks and the related transfers between the members of the monetary union are clearly the task of national fiscal policies, and only the national parliaments have the democratic legitimation to make such decisions. For this reason, the Eurosystem’s mandate to ensure price stability rightly involves the prohibition of any kind of monetary financing.

Yes it does but the blame for that is in the designers of the EMU in the first place. The fact that they deliberately chose not to create a “federal” fiscal authority that would be binding on all nations meant they had to go with this decentralised fiscal-centralised monetary arrangement.

The fiscal authority should pursue public purpose and if a particular “state” (member country) is struggling because of deficient aggregate demand then that authority has to ensure that public spending increases. That is how a federal system operates – if it is to act in a fiscally-responsible way.

In the EMU, no such capacity exists. It would be very difficult to achieve a federal EMU fiscal authority given the cultural and historical differences. That is why the common currency zone was misconceived in the first place. It was not an optimal currency area and will never be close to being one.

So in that system, it is not sensible to argue that the weaker member states have to be crushed because the stronger states (Germany) don’t want to assume some of the responsibility. The point is that there is little risk involved for Germany anyway if the ECB does fund Greek growth.

It might also mean that German firms wouldn’t have to bribe Greek government ministers to get them to continue buying arms and military equipment from them.

Conclusion

Whether the government issues debt or not to match its net spending (deficit) makes no difference to the inherent inflation risk embodied in any spending – private or public.

The issuing of bonds is really a portfolio swap and does not reduce the capacity of the private sector to spend at will should it desire to.

Tomorrow, the ABS publish the latest Labour Force data and I expect I will write about that.

Is the Australian Treasurer a wind-up doll?

Yesterday’s blog – Economy faltering – Australia’s wind-up Treasurer “We will cut harder” – made reference to the mechanically-driven automaton that masquerades as our Federal Treasurer.

Every time, some new economic news arrives – usually bad – his standard response is: “We will deliver a surplus in 2012-13 as promised”. Or when told that federal revenue is collapsing because growth is slowing because his government cut spending too fast and too early – his standard response is: “We will cut harder”.

I was asked to prove that the Treasurer is in fact a wind-up doll. Always willing to back up my claims, I sought out some documentary or visual evidence.

I just hope whoever is winding him up each day takes a day off and goes to the beach.

That is enough for today!

But Swanny Babe is the Worlds Best Treasurer.How dare you call him a Windup Doll.

Actually,I prefer Sock Puppet.

“Under a fiat currency system there is no need at all to issue debt.”

Therefore, under a fiat currency system the concept of public debt is inapplicable or makes no sense.

If I pay students in “buckaroos” so that individual work may serve collective purposes of class, which is the sense of “borrowing” buckaroos from students saving them in order to spend more “buckaroos”? And then to address the class saying they are liable for the “buckaroos” I “borrowed”?

Dear Bill,

As of November 4, 2011 the ECB has bought 183,019 million euros worth of bonds under the programme.

Shouldn’t it be billions rather than millions ?

Dear Tristan (at 2011/11/09 at 21:55)

It is 183 billion and 183,019 million. It is a comma not a full stop between the 3 and the 0.

best wishes

bill

@bill

haha, locales and punctuation differences 🙂

I’ve been in the UK for over 3 years now, and I still get caught by this one every time.

An official Euro website contained :-

Q : “Is there an official decimal ‘delimiter’ (fullstop or comma) between euro and cent?”

A : “There is no European rule on this. National rules and practices determine whether they use a fullstop or a comma.”

Perhaps that explains the problems. 🙂

Yes, some Europeans use (,) instead of (.) and vice versa. One can check this easily by checking data from the Banco de Espana website. The default version is Spanish and shows numbers as 1,25% and if one chooses the English version, you see 1.25%. One can check the reverse by looking at data in excel sheets.

What if you can’t grow? Europe has declining demographics along with other problems, if you a system which needs eternal growth to function you have a failed system.

Better to find a better one.

“and harms the credibility of the central bank in its quest for price stability.”

That really is the ECB in a nutshell. Vainly concerned about establishing it’s reputation as a very serious central bank. Yet by refusing to shoulder it’s obvious responsibility (because that would be “irresponsible”) it seriously undermines it’s own credibility not just in the eyes of ordinary Europeans but even, ha ha, among their own peers. I can only wonder what words Bernanke and Shirakawa utter privately about the ECB and fools like Trichet. If this is how the ECB is going to behave every time there’s a recession, then sooner or later my country will be in serious trouble as well. Heckuva job, Easy B.

Ceterum autem censeo, Euro esse delendam.