I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Bond markets require larger budget deficits

Today I have been reading all the documentation surrounding the proposals issued by the Bank of International Settlements to reform the regulatory system for international banking. These considerations then took me to an interesting paper from Deutsche Bank where they refute (albeit unintentionally) much of the media hysteria about exploding government bond yields and bond markets “closing governments down” because their deficits are “ballooning out of control”. In fact, the DB Report shows categorically that within the new regulatory framework that the BIS (and hence the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority will introduce), there is scope for larger budget deficits. In terms of the state of the Australian labour market and the very slow growth that the world economy will experience in the coming years, a further stimulus package is necessary. The DB Report implies that the bond markets would welcome it. Curious?

Typically the financial market commentators all run a similar line. But there are times when the game becomes clearer – when self-interest actually discloses things that the popular media do not care to report. When these disclosures are made you get a picture into the true nature of the monetary system and the way the government operates within it and impacts on the non-government sector.

Special Pleading Classic One

One classic instance of this type of event occurred in Australia in 2002. At that time, the thinning of the federal bond market was a topic of discussion during the Review of the Commonwealth Government Securities Market.

At that time, the federal government had been running budget surpluses since 1996 and economic growth was only maintained by the massive buildup in household debt which kept consumption expenditure afloat. It was an unsustainable growth strategy because the private sector cannot increasingly accumulate debt.

The stock adjustments arising from the surpluses saw the outstanding stock of federal government debt fall dramatically as the government systematically undermined private wealth holdings. As this was occurring, the key financial market players who had been vehemently demanding the conservative government retrench the welfare state, public fiscal exit plans and introduce widespread deregulation (the cries never really change to they) started to realise that the thinning bond markets were not in the best interests.

The Review was announced after the industry had lobbied the federal government relentlessly to salvage their own corner of corporate welfare.

You can read the Treasury Discussion Paper along with all the public submissions, including that produced by The Centre of Full Employment and Equity (written by myself and Warren Mosler) if you are interested.

In our Submission, we addressed several claims made in the Treasury Discussion Paper, which was released to accompany the review. We also addressed the claims made by the Sydney Futures Exchange that by eliminating the CGS market the government would “deny superannuants an A$ denominated (default) risk free investment for their retirement planning at a time of an ageing population and in a mandatory superannuation environment.”

We noted that what is not often understood is that Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) are in fact government annuities. That is, guaranteed income streams.

We also wondered whether the “free market” lobby that were making these points (about superannuation losing out) really wanted the private sector to have access to government annuities rather than be directing real investment via privately-issued corporate debt, as an example

The point is also applicable to claims that CGS facilitate portfolio diversification. Why would Australians want to provide government annuities to private profit-seeking investors? This clearly interferes with the investment function of private markets.

We argued that direct government payments be limited to the support of private sector agents when failures in private markets jeopardise real sector output (employment) and price stability. Later in the Report we detailed that this support should be largely confined to providing employment guarantees and that government endeavour be focused on the provision of first-class education, health, aged care and other activities which unambiguously advance public purpose.

In this context, we also demanded a comparison of this method of retirement subsidy against more direct methods involving more generous public health and welfare provision and pension support. No such comparison was ever forthcoming from the government or its private sector puppeteers who were both rushing to increase the surpluses and had actively promoted the reduction of welfare benefits that were being received by the disadvantaged Australians and wide scale deregulation and privatisation.

The financial markets had been leading voices at the time (and still) demanding the government cut its deficit and get the “public debt-monkey” off the back of the economy. The neo-liberal government fell into line and started to run massive surpluses (even though unemployment and underemployment was very high) and regularly announced how it was retiring the public debt.

It was truly ironical while the government was acting according to the wishes of the financial sector – once it became obvious that the “corporate welfare” part of the deal was threatened – the very same financial players sought reassurances from government that a minimum volume of public debt would be issued each year even though (in their own words) it was not required to fund any deficits – there were surpluses after all at the time.

It was incredible really that these characters who kept the line that debt is used to fund deficits – suddenly (but subtly) shifted their line demanding more debt even though there was in their own logic no need for it. The public never really were party to the debate – it was rather technical – and so they never really were exposed to the double-standards operating.

The whole Review and the subsequent decisions highlighted the hypocrisy of the “debt-monkey lobby”. It became clear to those in the know that the actual agenda operating was that the financial organisations (banks etc) wanted to get rid of all government support (welfare) unless it impinged on their own ability to live the high-life. Then it was fine.

In our Submission, we argued that the roles identified by IMF, Australian Treasury and the Sydney Futures Exchange among others for the government bond market are not justifiable on public good grounds. They were classic examples of special pleading by an industry sector for public assistance in the form of risk-free government bonds for investors as well as opportunities for trading profits, commissions, management fees, and consulting service and research fees.

Furthermore, and ironically, their arguments are inconsistent with rhetoric forthcoming from the same financial sector interests in general about the urgency for less government intervention, more privatisation, more welfare cutbacks, and the deregulation of markets in general, including various utilities and labour markets.

Specifically, government price level intervention into private markets is typically challenged by economists on efficiency grounds. What is not widely understood is that government bonds issuance is a form of government price level intervention in interest rate markets. The burden of proof falls on those arguing in favour of government bonds issuance to show that the market in question is incapable of viable operation without government intervention and will, unassisted, produce outcomes detrimental to the macro priorities of full employment and price stability. No such arguments have ever been convincingly presented.

We also noted a larger irony in the entire discussion – as all parties to the debate, including the Treasury omitted discussion of the primary role of government bonds in the context of a flexible exchange rate system – that is, to support the term structure of interest rates rather than to fund government expenditure. This omission subsequently undermined much of the validity of the arguments advanced.

Today … another classic case

I thought about this again today when I read a report published last Monday (February 22, 2010) from Deutsche Bank – Bond Supply – implications for Bank Liquid Asset Portfolios – thanks to The Age economics writer Peter Martin for the link.

The DB document (from its Sydney branch) notes that:

We think it very likely that the 2010 Budget will project a much lower peak in gross Commonwealth debt than was the case in the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook. While good news for the Government, a lower peak and the likely intent by the Government to start repaying this debt as soon as it can has implications for the proposed reforms to bank liquidity arrangements.

First, they are noting that our misanthropic federal government (at least when it comes to the unemployed) is talking big about getting the deficit back into surplus as soon as possible and reducing the debt burden we are allegedly leaving to our grandchildren. They have devised some ridiculous formulas (fiscal rules) that they will implement to achieve these aims.

The Government will never learn it seems. A return to the pursuit of surpluses will ultimately be self-defeating. For all practical purposes any fiscal strategy ultimately results in a fiscal deficit as unsustainable private deficits unwind. But these deficits will be associated with a much weaker economy than would have been the case if appropriate levels of net government spending had have been maintained.

The Government rehearses the conservative logic that by running budget surpluses they are “saving” and these “resources” are then able to be used by the private sector. The government sees a virtue in retiring net government debt. But a government surplus is an equal reduction in non-government net income and net financial assets.

This net income and resulting net financial assets serve as the “equity” that supports the private sector’s credit structure. By removing this net income and net financial assets, government budget surpluses undermine the credit structure, which ultimately readjusts to its reduced equity base as Hyman Minsky showed in his writings in the 1980s.

The economy will only sustain high levels of output after the government realises deficits sufficiently large to restore necessary income and equity to support an expanding private sector credit structure.

Further, the Government does not require budget surpluses to retire debt. The government can retire debt at any time it wants by using the RBA’s support rate rather than public debt for interest rate support when it net spends.

Additionally, the RBA always has the open option to purchase and thereby retire remaining public debt outstanding. Again, this simply exchanges one private sector asset, public debt, for another, RBA member bank balances.

While net taxation revenue will also retire debt, we repeat that this will ultimately not reduce cumulative government deficit spending and therefore in the long term not retire debt.

It is fare better to let market forces determine the level of government deficit spending. A fixed-wage Job Guarantee policy can attenuate any tendency towards financial instability and provide the “switch” between private and public sector employment over the business cycle, as well as provide an anchor effect to the price level.

I have always found it ironic that during a time of heightened appreciation of market forces, the option to let market forces determine the size of the fiscal deficit has not been open to discussion. But in saying that I do not find it surprising, as the presumed fixed exchange rate assumptions and restrictions take precedence.

Second, what about these “proposed reforms to bank liquidity arrangements”? Before I look at them we need some background.

Basel I and II

The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) convened the so-called Basel Committee on Banking Regulations and Supervisory Practices (known initially as the Cooke Committee) in 1974 in reaction to the growing international financial instability. The initial concern was to provide a level playing field in international banking. But declining capital levels would also come to the fore.

They sought to develop a common minimum standard of capital adequacy that all international banks should maintain. They wanted to ensure stability of the international financial system but allow the banks freedom to determine their own portfolio choices and allow competition.

Basel I

As the potential for major international bank failure grew as risk levels were rising, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision which at that time comprised central banks and supervisory authorities of 10 countries met in 1987. The work culminated in the Basel Capital Agreement published in July 1988 (which was called Basel I).

The methodology defined a “minimum” amount of capital that banks should retain – the minimum risk-based capital adequacy. You can read up on the details HERE

Several amendments have been made to the original accord.

The new approach to regulation no longer prescribed the asset composition of the banks’ balance sheets. Earlier approaches forced banks to hold certain types of assets (government bonds) in strict proportions. This system of regulation was ineffective because the banks were continually innovating and taking business “off the balance sheet”. For example, banks started to own finance companies which were not subject to regulation.

The Basel I approach, however, still gave banks a wide freedom to lend. But banks with high risk lending strategies were “forced” to hold a relatively high proportion of shareholder equity.

Sticking points were how to define capital (which was essential if they were going to impose capital adequacy.

Capital plays a very different role in the bank than it does in the corporation.

In the latter case, capital facilitates the transfer of ownership of assets, profits, etc to shareholders. Capital is also a means of raising funds through share issues. So that rising debt/equity ratios will usually push the cost of debt up and force the firm to resort to equity for further expansion.

But banks can have virtually unlimited leverage and the amount of debt a bank can raise depends more on its perceived safety than its debt/equity ratio. For a bank, the liability side does not exist purely to fund the activities of the bank. It is a part of the activities of the bank. They can (in theory) borrow whatever they need as part of their normal activities of intermediation.

An essential role of bank capital is to act as a buffer against losses. It is the last line of defence against losses.

Basel I defined a two-tiered capital classification:

- Tier 1 (Core Capital) – are funds permanently dedicated to the solvency of the company. They constitute the highest quality capital. They allow the bank to keep operating despite suffering some losses. It includes – Paid-up ordinary shares; Non-repayable share premium account; General reserves; Retained earnings; Non-cumulative irredeemable preference shares; Minority interests in subsidiaries.

- Tier 2 (Supplementary Capital) – is a less primary or reliable form of protection. Rather than being supplied by shareholders it is the product of the bank’s activities. It cannot be as easily converted into liquid funds. It includes – General provision for doubtful debts; Asset revaluation reserves; etc

They then defined the risk-weighed assets in the following way:

| Asset Type(s) | Weight (%) |

| Currency, gold, short-term (< 12 months) federal government bonds, Balances with the central bank | 0 |

| All other government bonds, claims on OECD governments, local currency claims on non-OECD governments | 10 |

| LGS and semi-government securities of non-commercial bodies (foreign and domestic), claims on banks (excluding long-term claims on non-OECD banks) | 20 |

| Loans secured by residential mortgage (for loan-to-valuation ratio is less than 80%) | 50 |

| Claims on non-commercial public enterprises, claims on corporations and NBFIs, housing loans (loan-to-valuation ratio > 80 per cent) | 100 |

Then the capital adequacy requirements were expressed in terms of a:

minimum capital ratio = Core Capital plus Supplementary Capital divided by Risk-weighted assets

The ratio of capital to risk-weighted assets had to be at least 8 per cent. Core capital had to be at least 4 per cent. This minimum applies to the bank and the consolidated group, except insurance company and funds management subsidiary operations.

The 1996 amendments introduced market risk. Market risk arises when there are price changes in debt instruments, equity, commodities and forex exposures. A bank’s market risk exposure is determined both by the volatility of the underlying risk factors and the sensitivity of the bank’s portfolio to movements in those risk factors.

Banks face market risk from a full range of positions held in their portfolios but the capital standards focus on the market risks arising from the bank’s trading activities. Thus market risk is considered to be a component of the trading activity and because the positions are marked to market each day they are more visible.

The substitution of the banks’ internal risk management systems for broad, uniform regulatory measures of risk exposure is said to lead to capital structures which more closely reflect individual bank’s true risk exposure. This refers to the use of an internal models approach.

The new guidelines also include qualitative standards. Any bank must be able to demonstrate that it has a sound risk management system. The risk estimates must be closely integrated with the risk management process.

Banks must keep credit control units separate from the units that generate the market risk exposure. The experience of Barings PLC contributed to this requirement. They must conduct independent reviews.

Basel I was not very effective for many reasons, including:

- There was only a partial differentiation of credit risk – the 4 categories in the table above.

- The 8 per cent capital ratio was static and didn’t reflect changing market circumstances (rising risk).

- There was zero recognition of the term-structure of credit risk – that is, they did not incorporate the “maturity of a credit exposure”.

- They did not properly recognise portfolio diversification effects.

Basel II

There were other problems and this led to the 2007 Basel II Capital Accord. You can read all the changes introduced by Basel II HERE. Essentially it added “operational risk” (losses arising from human error or management failure) and defines new ways of calculating credit risk. New approaches to assessing these risk exposures were recommended.

The problem with the Basel framework is that it gave banks an incentive to underestimate credit risk. The banks are allowed under the framework to use their own models of risk assessment to reduce the required capital and increase returns. Part of those returns are the fabulously large bonuses that are now common in private banking.

It is clear the managers failed to allocate adequate capital as the risk exposure of their banks was increasing rapidly in the lead up to the crisis. It is clear that a system of self-regulation and the ability to under report risk failed.

Latest Basel developments

In December 2009, by way of reflection on the current crisis, the BIS issued a new paper – International framework for liquidity risk measurement, standards and monitoring – which proposes further changes to the international regulatory environment for banks.

This is the document that the DB Report I referred to above is talking about.

The BIS Discussion Paper notes at the outset that:

Throughout the global financial crisis which began in mid-2007, many banks struggled to maintain adequate liquidity. Unprecedented levels of liquidity support were required from central banks in order to sustain the financial system and even with such extensive support a number of banks failed, were forced into mergers or required resolution. These circumstances and events were preceded by several years of ample liquidity in the financial system, during which liquidity risk and its management did not receive the same level of scrutiny and priority as other risk areas. The crisis illustrated how quickly and severely liquidity risks can crystallise and certain sources of funding can evaporate, compounding concerns related to the valuation of assets and capital adequacy.

They say that a given a “key characteristic of the financial crisis was the inaccurate and ineffective management of liquidity risk” regulative changes have to be made to “for banks to improve their liquidity risk management and control their liquidity risk exposures”.

One of the changes to the Basel framework proposed in this document is the introduction of better liquidity risk supervision. In that context, they propose some new standards, one of which is the introduction of a Liquidity Coverage Ratio, which will represent “minimum levels of liquidity for internationally active banks”.

The BIS say that:

The liquidity coverage ratio identifies the amount of unencumbered, high quality liquid assets an institution holds that can be used to offset the net cash outflows it would encounter under an acute short-term stress scenario specified by supervisors. The specified scenario entails both institution-specific and systemic shocks built upon actual circumstances experienced in the global financial crisis.

You can see that the regulatory environment is shifting back towards asset composition – a focus which was abandoned when capital adequacy became the main regulative approach.

In the proposals, the BIS discuss what constitutes a reasonable definition of liquidity for these purposes. High quality assets would include cash, sovereign debt, non-central government public sector entities and a number of Supras (but conditionally specified).

These assets would have to comprise more than 50 per cent of the overall required stock.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) “is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, credit unions, building societies, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry.”

In December, following the BIS publication, APRA released a discussion paper. You can read their detailed responses to the Basel proposals HERE.

Essentially, the main issue here is the definition of liquid assets. APRA considers that:

liquid assets should be high quality assets that can be readily sold or used as collateral in private markets, even when those markets are under stress … sovereign bonds will be the assets that most clearly satisfy these criteria.

Why does all this matter?

Back to the DB Report

The DB Report argues that the proposed BIS changes which APRA will oversee in Australia are being:

… developed against a backdrop of significant government bond issuance. Thus it envisages government debt forming a substantial portion of liquid assets. In the Australian context, this will not be possible – a point that will be emphasised by another significant downward revision to the projections of government debt in the May Budget.

Commenting on the implications of the proposals in the new BIS report, DB says:

In particular, it means that the stock of commonwealth and semi-government debt will almost certainly be insufficient for bank liquidity purposes. It is inevitable, in our view, that Supra and agency debt will be included in the pool of high quality assets as a consequence. But even this will not provide a large enough pool of liquid assets for the banks … unless the liquidity buffer is kept relatively small.

So what does that mean? Several things.

Bond yields are not affected by volume

First, the DB Report argues that:

… the prospect of less debt has much implication for the level of Australian bond yields. After all, to be consistent with our view that increased supply would not pressure rates upward we have to think that a smaller peak in supply will not push rates lower.

I wonder why News Limited and all the other right-wing lacky media outlets didn’t give this opinion (from one of the large investment banks) any exposure?

The reason is simple it would not have suited the uninformed hysteria that they pump out each day about yields exploding and bond markets refusing to fund government deficits.

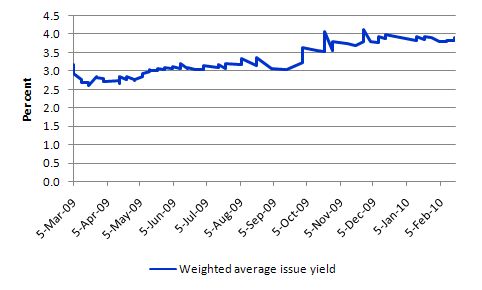

The fact is that bond yields have barely moved over the course of the public debt build-up. Consider the following graph.

The first graph shows the weighted on Australian government Treasury note issues since March 9, 2009 to February 18, 2010. The data is from the Australian Office of Financial Management. The modest rise in yields has followed the movement in the RBAs target interest rate which was pushed up in late 2009.

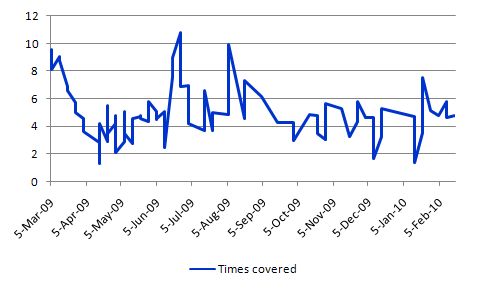

There has also been a huge demand for the public debt in Australia. Consider the following graph which shows the time covered or bid-to-cover ratio which is just the the $ volume of the bids received to the total $ volumes desired. So if the government wanted to place $20 million of debt and there were bids of $40 million in the markets then the bid-to-cover ratio would be 2. Some people claim that this provides a signal of market appetite for debt.

Please read my blog – D for debt bomb; D for drivel … – for more discussion on this point.

First, the use of the ratio assumes it matters. It doesn’t because the Australian Government is not revenue-constrained so it could just abandon the auction system whenever it wanted to if the ratio fell to 0.00001.

Second, it is highly interpretative as to what the ratio signals. It certainly signals strength of demand but how strong becomes an emotional/ideological/political matter. Even if you believed that the government was financing its net spending by borrowing, then a bid-to-cover ratio of one would be fine – enough lenders to cover the issue. Some commentators think that 2 is a magic line below which disaster is imminent. There is no basis at all for that.

There is also no basis in the statement that a ratio above 3 is successful and by implication a ratio below 3 is unsuccessful. After all, anything above 1 tells you that some investors do not get their desired portfolio. That sounds like a failure to me.

The data is again provided by the Australian Office of Financial Management. Remember a ratio of 1 means that there is enough demand to match the issuance intentions of the government.

Not enough public debt

Further, DB is worried that if the federal government returns to surplus then the bond supply into the markets will dry up.

In this context they do some calculations based on estimated trends in budget parameters. They say:

If we assume for illustration purposes that a bank’s liquidity reserves needs to be 10% of assets, then the current Australian banking ‘system’ would need to hold a stock of around $200 billion in liquid assets. Even in a few years time the total stock of outstanding ACGB and Semi-government debt is unlikely to be much more than $300 billion … Hence under the Basel liquidity proposals the bank will need to own at least a third of the ACGB and Semi market within a few years – which implies a potentially significant maturity mismatch given that much of this debt is long-term.

While they go onto to discuss other related issues like the need for a “covered bond market” and Supra and AAA-rated agency debt to be included in the defintion of liquid assets for regulatory purposes the point and implications are clear.

While this case is not of the same ilk as the special pleading in the first vignette that presented above (from 2002), the points are clear. As new regulatory rules are introduced by prudential authorities, the demand for liquid assets by banks will rise. The demand is already high and not even close to exhaustion (see data above).

But these liquidity rules will expand the scope for debt issuance without invoking any unfavourable reaction from bond markets.

It also means that if the government wants to maintain the voluntary constraints that it imposes on itself to match all net spending $-for-$ with debt issuance into the private markets, it can also start issuing short-term Treasury notes (at lower yields) and reduce the long-term debt is issues. That would overcome the bankers’ concerns about maturity mismatch.

But the preferable solution is for the government not to issue any debt at all and just pay interest on reserves (preferably close to zero) which would satisfy the liquidity requirements of the proposed new regime.

While the banks would not want this option (because they enjoy the guaranteed public handout – income from the interest payments) it would be preferable from a societal perspective because the whole machinery of bond issuance could be abandoned – with the real resources freed (labour etc) to perform socially useful tasks.

As an aside, some people think the interest payments are not an income to the non-government sector in the sense that the tender price is usually discounted to incorporate the yield. That doesn’t alter anything other than the accounting entries. The non-government sector still enjoys a guaranteed return on the funds they put into the bond purchases.

Conclusion

Once again insights into how things actually work out there in real world land often come from odd sources and are usually disclosed when self-interest forces the discussion to get away from the hype and hysteria and instead focus on reality.

The DB Report, in my view, clearly is an example of that even though that was not their actual motive. They were lobbying for lower liquidity requirements and a broader spectrum of assets to be included in the definition.

But you can equally conclude that as the banking sector grows the appetite for more public debt would be substantial and yields would not be impacted by this growth in demand.

What this means is that under given the voluntary constraints that the federal government imposes on itself to match all net spending $-for-$ with debt issuance into the private markets, there will be considerably larger scope for the bond markets to absorb the public debt under the guidelines proposed by the BIS without pushing up yields.

That insight alone knocks the debt hysteria on the head.

Further, the budget deficit should expand until there is full employment. Given the spending preferences of the non-government sector, the effective and desirable limit on net public spending is reached when capacity is being fully utilised.

At present, we are a long way from that point. So a third stimulus should be implemented in the May Budget which will also ease the concerns of the bond markets who will welcome the extra high quality liquid assets in the face of new banking rules coming out of Basel III.

I also find it interesting that the popular media just ignores this sort of report but instead continually promote discussion papers and statements that present the hysterical side of the debate.

Finally, this is another example of “if only the public knew what the real story was – they would react and vote differently”.

That is enough for today!

http://www.talkfinance.net/ steve keen has launched a forum to discuss economics and issues brought up by his blog. there is a chartalist vs circuitist thread under talking theory i suggest other mmt people post on and explain mmt much better then my pathetic attempts. i also suggest bill to post his blog under the blog wrapup part.

I enjoy reading your blog and the MMT thinking seems very reasonable to me. But it is also very frustrating to read your entry in the morning (I’m situated in Europe) and then continue reading other stuff. Today I encountered this blog entry “So How’s That Fiscal Stimulus Working For You?” (http://bit.ly/cRdexV) from Steven Landsburg referring to Robert Barro’s column in the WSJ: The Stimulus Evidence One Year On (http://bit.ly/d09kKH) Look’s like the battle against mainstream pseudo-academia is somehow a hopeless endeavour.

Nathan,

Nice work. Two quick things. First, I and every other chartalist I know would avoid using the term “money” whenever you start getting into accounting. Say which liability you are talking about, as “money” is always someone’s liability and saying “money” only provides LESS clarity regarding which. Second, I just don’t have the stomach to post there for now–maybe someday, but not now. I’ve spent a good chunk of time time in conversations on that blog and I’ll never get those hours back no matter how long I live. I’ve come to understand for now after discussing there and other places that if others aren’t interested in learning a little bit of accounting, you’re not going to get far if you try to have any sort of somewhat technical discussion about the details of the monetary system. There are some discussions for which some accounting isn’t all that necessary, but discussants there want to go a bit deeper, but can’t because they can’t do the accounting, but they don’t agree and there’s no way to convince them otherwise (not all of them, but most).

Best,

Scott

Interesting story on front page of FT this morning (2/24): “Fed efforts boosted by Treasury’s $200 bn debt plan” – why the boost – well this will help Fed drain excess reserves – I believe there is an admission in there somewhere. Remember not too long ago the “sky was falling” – OMG Fed’s balance sheet will lead to inflation – OMG U.S. debt is going to destroy the world. Oh wait – this is OK.

Stephan –

As for Barro, interesting that he talks about “added obligations must be paid for sometime by raising taxes” & “government has no free lunch and must collect the extra taxes eventually”. Based on HIS logic, same could be said about huge tax cuts given to the Top 4% under Bush or even huge tax cuts under Reagan – because, again based on his logic, there is “no free lunch” if you obsess about the federal deficit. Unless, of course, you believe that tax cuts “pay for themselves” but still that is a problem because again if you are concerned about the deficit – the tax cuts didn’t pay for themselves.

Bill, excellent posting and a very enjoyable read.

I have a couple of things to add that people may want to comment on.

One interpretation of the shortfall in “liquid assets” as defined under Basel is that there are not enough government assets (reserves or bonds) in the economy (as you’ve argued here and elsewhere), and more should be issued.

Another possibility is that the banking system is too large for the economy. In some ways this interpretation is more consistent with what the Basel rules are trying to do – prevent the banking system from destabilising the economy – as it could do if a very large banking system is perched upon a very small “liquid asset” base.

Some might argue that expansion of the banking system allows real growth (and should not be curtailed), but if you examine the credit statistics over the last 10 to 15 years, it’s clear that bank assets (private debt) have increased relative to GDP, suggesting that the credit has gone into funding “unproductive” pursuits. In fact almost all of the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 15 or 20 years can be attributed to growth in residential mortgages for owner-occupiers and investors.

It might be fair to say that housing is not actually an unproductive asset, but that some of the things it produces (like satisfaction, happiness or safety) are not captured in GDP figures, but are still real. There is some truth in this, but it is completely subjective, and I would have to question how much of this intangible benefit has been underwritten by generally rising prices over the last 15 years.

@RebelCapitalist

I think the reason why these unfunded tax cuts don’t cause any concerns for this sort of thinking stems from another conservative/neo-liberal believe “Starving the Beast”. Of course this starvation theory is another myth belonging to many other zombie ideas walking around and showing up regularly in the news to proof they’re not dead yet.

Bill:

I remember in early 2000, when the US election was staring up and there was Democratic boasting about “paying down the debt” with all these surpluses being forecasted. Greenspan and Rubin then made some obscure comments about how that might not work out so well and it needed to be thought through, etc., etc. It kind of surprised me back then, but I really didn’t have a clue about how monetary systems worked (a little more now, I hope). In retrospect it appears to be another case of “take us seriously when we want you to, but don’t try to go to any logical conclusions on your own – let the experts run things.”

Mankiw watch : http://www.wellesleywestonmagazine.com/spring10/facetoface.htm

PEBIRD: don’t know about greenspan but rubin was on roadshow boasting about how cutting deficit lowered interest rates and lead to economic boom under clinton. He is top 10 financial terrorist list

Interesting article by Michael Pettis on USD/China balances.

http://mpettis.com/2010/02/what-the-pboc-cannot-do-with-its-reserves/

I like this quote:

“Because when the PBoC decides on the level of the RMB against the dollar, it does not do so by passing a law, and making it a capital crime for anyone to trade at a different price. What it does is far simpler. It offers to buy or sell unlimited amounts of RMB against the dollar at the desired price.

No one will sell dollars for less than what they can get from the PBoC, nor will anyone buy dollars for more than what they can pay the PBoC, so all transactions get done at that price. That is how the PBoC (or any other central bank that intervenes in the currency market) sets the foreign exchange value of its own currency.”

It seems analogous to how a Central Bank sets interest rates using its open market activities.

Agree with Zanon. I remember buying my first house in 2000 and hearing Prez Clinton tell us how the surplus was reducing our mortgage rates. My mortgage rate was 9%. Less than 2 years later, the $200B surplus was a $400B deficit and I refinanced at under 6%.

This may be slightly off topic, but I am a little confused about how bank loans create deposits. I think I pretty clearly understand that on the demand side banks are limited in their ability to make loans by the number of creditworthy customers in the economy. However, I am less sure I understand the supply side of the equation. I get that capital requirements set by domestic and international regulators restrict the ability of banks to make loans, but I get confused as to what counts as bank capital. Specifically, I’d like to know if the money that everyday folks like me put into our regular savings accounts count as capital banks can use to satisfy their capital requirements. Maybe I’m misinterpreting Professor Mitchell’s writing here, but in the description of tier 1 (Core) capital requirements above “general reserves,” are included. But if general reserves count toward the the amount of capital banks have to keep on hand wouldn’t that imply the amount of reserves banks have on hand do play a factor in determining banks’ ability to make loans (on the supply side)? And isn’t a core tenant of MMT that the amount of reserves banks hold plays no or very little role in banks’ decision to make loans? Is it just that I’ve misinterpreted what “general reserves,” means?

Regarding Barro that used to be one of my teachers. He always seemed to be interested to say what would benefit his carreer. First his work in disequilibrium/non clearance markets with Grossman, then shifted due to rational expectations to Feldstein ideas aout Ricardian equivalence and public debt is not wealth and then his fixation with the crowding out effect. By the way I think I did the first study on the crowding out effect back in the 70s and I found none of it and my MA thesis supervisor a Chicago boy went crazy blaming the computer! Barro fails to realize that he does not measure the potential contraction that would have occured if the stimulus program was not enacted and the effect of the build in stabilizers because these cannot be captured accurately in the data. Furthermore, future tax liabilities are hard to estimate since we do not know who will be eligible to pay ( for example high mps), how the stimulus is spent and how sustainable is the return from it net of the relative low interest rates from the Federal Reserve policy. Thus his calculations has a lot of unknowns and I see no crowding out as long as resources are underemployed and interest rates stay relatively stable which is supported further by the liquidity ratio discussed in this blog.

“Nathan,

Nice work. Two quick things. First, I and every other chartalist I know would avoid using the term “money” whenever you start getting into accounting. Say which liability you are talking about, as “money” is always someone’s liability and saying “money” only provides LESS clarity regarding which. Second, I just don’t have the stomach to post there for now-maybe someday, but not now. I’ve spent a good chunk of time time in conversations on that blog and I’ll never get those hours back no matter how long I live. I’ve come to understand for now after discussing there and other places that if others aren’t interested in learning a little bit of accounting, you’re not going to get far if you try to have any sort of somewhat technical discussion about the details of the monetary system. There are some discussions for which some accounting isn’t all that necessary, but discussants there want to go a bit deeper, but can’t because they can’t do the accounting, but they don’t agree and there’s no way to convince them otherwise (not all of them, but most).

Best,

Scott”

thank you very much scott. i always have trouble decribing the accounting precisely. the people on the thread seem to be willing to learn more about chartalism, i”m optimistic. a side note, i was wondering if there was anywhere i could read more and get deeper into the accounting of chartalism/ learn how to start modelling

“NKlein1553 says:This may be slightly off topic, but I am a little confused about how bank loans create deposits. I think I pretty clearly understand that on the demand side banks are limited in their ability to make loans by the number of creditworthy customers in the economy. However, I am less sure I understand the supply side of the equation. I get that capital requirements set by domestic and international regulators restrict the ability of banks to make loans, but I get confused as to what counts as bank capital. Specifically, I’d like to know if the money that everyday folks like me put into our regular savings accounts count as capital banks can use to satisfy their capital requirements.”

no. your deposit is like money you lent to the bank, its the bank’s liability. money owed to the bank and the things/state money banks own are the banks assets.

Hi Nathan,

I’d start with Bill’s blog on stock-flow consistent modeling. There are a number of links there. You can also look at his recent blogs on the simple business card economy models. Then it depends on what you want to start modeling. If you want to do more broad macro modeling, then I’d go to the papers at http://www.levy.org by Godley, Lavoie, Zezza, and Dos Santos. If you want to do more in the area of monetary operations, then I can make some suggestions there. Also, a 1st semester accounting textbook would be good–most any will do, as that’s not an ideologically-driven field like economics.

Maybe others have some suggestions, too.

Best,

Scott

Dear Scott,

“If you want to do more in the area of monetary operations, then I can make some suggestions there.”

What sort of operations do you mean? A couple of examples? And what are the suggestions you can make?

Thanks

Graham

i”m very interested in monetary operations. i would consider myself a minskyian and am interested in creating not only a stock flow consistent model that can create endogenous financial instability (i know there are many) but also logical functions would logically lead to that instability.

NKlein1553 said: “This may be slightly off topic, but I am a little confused about how bank loans create deposits. I think I pretty clearly understand that on the demand side banks are limited in their ability to make loans by the number of creditworthy customers in the economy.”

And the interest rate?

“However, I am less sure I understand the supply side of the equation. I get that capital requirements set by domestic and international regulators restrict the ability of banks to make loans, but I get confused as to what counts as bank capital. Specifically, I’d like to know if the money that everyday folks like me put into our regular savings accounts count as capital banks can use to satisfy their capital requirements.”

I think the answer is no. I believe you are talking about risk here. Checking and savings accounts should have zero risk. If they get “lent” out, it should be thru the overnight fed funds market.

Feel free to correct me if I am wrong.

Here is one last thing. What restricts the ability of banks to make loans if the capital requirement is zero?

Nathan Tankus, I would suggest personal finance of the lower and middle class. Specifically, that the lower and middle class can be suckered into believing expectations of price inflation, hourly wage inflation, and hours worked inflation that don’t turn out to be true to “trick” them into going into debt to the rich in the present so the rich can maintain their excess savings.

RebelCapitalist said: “Interesting story on front page of FT this morning (2/24): “Fed efforts boosted by Treasury’s $200 bn debt plan” – why the boost – well this will help Fed drain excess reserves – I believe there is an admission in there somewhere. Remember not too long ago the “sky was falling” – OMG Fed’s balance sheet will lead to inflation – OMG U.S. debt is going to destroy the world. Oh wait – this is OK.”

And, from:

http://www.econbrowser.com/archives/2010/02/treasury_supple.html

“First a little background. Whenever the Federal Reserve buys an asset or makes a loan, it simply credits new reserve deposits to the account that the receiving bank maintains with the Fed. The bank would then be entitled to convert those deposits into physical dollar bills that it could ask the Fed to deliver in armored trucks. Banks currently hold $1.2 trillion in such reserves, or more than a hundred times the average level of these balances in 2006, and more than the total cash the Fed has delivered since its inception a century ago. The traditional way the Fed would bring those reserves back in (and thus prevent them from ending up as circulating cash) would be to sell off some of its assets.

The Treasury’s Supplementary Financing Program was introduced in the fall of 2008 to assist the Fed in its massive operations to prop up the financial system at the time. The SFP represents an alternative device by which the Fed could reabsorb the reserves it created. Essentially the Treasury borrows on behalf of the Federal Reserve, and simply holds the funds in the Treasury’s account with the Fed. When a bank delivers funds to the Treasury for purchase of a T-bill sold through the SFP, those reserve deposits move from the bank’s account with the Fed to the Treasury’s account with the Fed, where they now simply sit idle, and aren’t going to be withdrawn as cash. In a traditional open market sale, the Fed would sell a T-bill out of its own portfolio, whereas with the SFP, the Fed is asking the Treasury to create a new T-bill expressly for the purpose. But in either case, the sale of the T-bill by the Fed or by the Treasury through the SFP results in reabsorbing previously created reserve deposits.”

Could the banks have taken the excess reserves, converted them to currency, used the currency as 0% risk weighted bank capital, and then made loans “against the currency/capital”?

“Fed Up says:

Thursday, February 25, 2010 at 18:03

Nathan Tankus, I would suggest personal finance of the lower and middle class. Specifically, that the lower and middle class can be suckered into believing expectations of price inflation, hourly wage inflation, and hours worked inflation that don’t turn out to be true to “trick” them into going into debt to the rich in the present so the rich can maintain their excess savings” decent suggestion; my train of thought has lead me somewhere different so bear with me. as time passes the average persons willingness to dissave (whether by spending past savings or taking out a loan) increases proportionally to asset prices increase and decreases proportionally as asset prices decrease. i am unsure how to make that a workable function or how to integrate it into a consistent stock flow model.

Not related to the post.

The BIS author Piti Disyatat has written a new paper http://www.bis.org/publ/work297.pdf?noframes=1

Talks of Endogenous Money and cites Randy Wray, Thomas Palley, Basil Moore . . .

NKlein1553,

reserves that count to capital are the ones that banks hold against projected losses. Another word for these is (loss) provisions.

The MMT reserves are a completely different story, ie interbank settlements and reserve requirements at CB. Two universes but one word

A related question then: what are the reserves that quantitative easing adds to? When the Federal Reserve swaps currency for bonds, mortgage backed securities, and other various long term assets banks hold that are of dubious value does that extra currency count toward the capital banks must hold against projected losses? If so, wouldn’t that mean quantitative easing has the potential to increase the capacity of banks to make loans contrary to Professor Mitchell’s Quantitative Easing 101 post?

NKlein, QE means that the Fed expands its balance sheet by purchasing securities from banks. The Fed gets the securities and the banks receive reserves. The securities are Fed assets and the reserves in exchange are Fed liabilities. The Banks just transfer one asset type for another. Securities which were illiquid for reserves, which are liquid. GE increases banks’ liquidity, supposedly to enable them to make loans.

Bank capital relates to provision against insolvency. It’s the equity put at risk in an enterprise. Assets = liabilities + equity. Put simplistically, a banks assets are its loans (receivables) plus what it owns outright. Its liabilities are its deposits, which it has to cover on withdrawal. The loans represent risk. That which the bank owns outright is free and clear. Positive cash flow means that the entity has enough funds on hand to cover its day to day outflow through operations.

The bank owns the loans (receivables) it has made, and like a business, can sell its receivables. This is called factoring. This is what the banks do with securitization. Usually, a firm must factor its receivable as at a discount commensurate with risk of non-payment, but in the banks’ case they figure out how to finagle things so that they factored the loans at a markup instead of a markdown. Pretty clever. But what it did was increase systemic risk. This is the essence of the present financial crisis.

Anyway, banks have to hold capital (outright ownership) against possible loan default (non-payment of receivables). This is the capital requirement that limits leveraging capital in loan extension. Moreover, not all capital is liquid and so banks have to hold liquid reserves against potential losses from default. This is working capital, so to speak, that is a liquidity provision against negative cash flow. The liquid reserves are Tsy’s owned by the bank, for example. Illiquid capital includes stock owned by stockholders, which is at risk in the event of insolvency.

Reserves held with the CB are a liquidity provision for settlement of accounts in interbank transactions, e.g., check clearing. This liquidity provision is different operationally from reserves as a provision against loss.

For an intro to macro based on accounting and stock-flow consistency instead of the usual theoretical models, see Wynne Godley and Francis Crispin, Macroeconomics (1982). It’s out of print but there are used copies available.

Check http://www.bookfinder.com

The definitive work is Godley and Lavoie, Monetary Economics (2007).

Thank you Tom, Sergei, Nathan, and Fed Up. I appreciate the instruction.

Ramanan: I havent read the BIS paper yet, starting now. The abstract says this “A central proposition in research on the role that banks play in the transmission mechanism

is that monetary policy imparts a direct impact on deposits and that deposits, insofar

as they constitute the supply of loanable funds, act as the driving force of bank lending.

This paper argues that the emphasis on policy-induced changes in deposits is misplaced.”

Do they concede that there are really no “LOANABLE FUNDS”?

Thanks

LOL! from the BIS paper that Ramanan posted

“There is no quantitative constraint as such. Confusion

sometimes arises when the flow of credit is tied to the stock of savings (wealth) when the

appropriate focus should in fact be on the flow.”

Bill, Randy and all the coworkers have been emphasizing this enough for a while. Is Piti Disyatat mainstream? Hopefully the understanding will spread around and policy makers will start seeing sense.

This isn’t a bad quote from the BIS paper either: “The absence of a link between reserves and bank lending implies that the money multiplier

is an uninformative construct.”

Dear pebird

Yes a lovely quote.

I guess Mankiw and all the others are busily working away revising their textbooks.

The problem is that once they work out what is wrong in them that has to be changed they will quickly find that the remaining valid content will consist of a front and back cover only.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

LOL! front and back cover! Ha ha ha . . .

Of course bond markets love deficit spending. They get skittish if there is risk of default or inflation, but in general they love it.

Everyone wants someone else to be responsible for funding demand for their products, or for providing income to their debtors. Deficit spending allows *no one* else in the private sector to bear this burden. It is a free lunch for capital that has reached a state of disequilibrium in which there is demand failure.

As a result, the decision to deficit spend creates an additional flow of income to capital that would not have been there without this spending. This flow of income is the true “government annuity” that is being provided. And it is the only government benefit that is provided to the economy or to capital markets.

If this flow of capital income is properly priced (and it may not be, but on average it will be), then should the government offset deficit spending with bond sales, the market value of the debt will be the market value of the capital income boost due to deficit spending.

The complaining about the private sector “benefiting” from coupon payments is misguided — the private sector benefited from the deficit spending when it occurred. The private sector, should have accepted lower returns by some combination of increasing wages, suffering defaults, or lowering prices. The government has the power to coordinate this at the macro level via individual and business taxes, bankruptcy laws, and bank regulation.

Alternately, the government can just supply more revenue. This is easier, does not tackle vested interests, and makes everyone happy, including the bond markets.

But in this case, capital obtains higher returns than they otherwise would have. And if the government does a bit of each, then the difference is measured in the size of the deficit.

Now some coordination problems are too hard to solve — prices are sticky and you cannot expect the private sector to accept continuous deflation as the economy grows. So the deficit needs grow at least with the size of the economy. But constantly growing deficits as a share of the economy means that there are more problems than just sticky prices. The government is not doing its job in ensuring that wages are high and private sector debt levels are low.

So if your view of the world is through the lens of the (government controlled) interbank market, then bond sales prop up the (nominal) call money rate, but only because you have configured the banking system to operate this way — it is completely up to the currency issuer to set call money rates and how they respond to any other variable in the economy. Whether banks benefit from holding bonds as opposed to reserves is also completely up to government to decide via appropriate bank policy, reserve interest payment policy, or bank funding policies more generally.

But if your view of the world is through the lens of the economy and capital markets, then deficit spending props up the (nominal) rate of return, whereas bond sales have no effect.

The latter is because deficit spending provides the assets needed to purchase the government bonds. Everyone who buys a bond must sell some other asset (whose value has increased due to deficit spending) of equal value first, and the expected return of the asset sold is equal to the expected return of the bond. Moreover, each time a coupon payment is made, the value of the bond decreases by the amount of the payment, leading to no net increase in the net worth of the bond holder, or of the private sector as a whole. So neither in the sale of the bond nor in the act of paying a coupon is capital enriched (on average). The deficit spending is what enriches capital. The coupon payments on government bonds are just a visible measure of the income boost that the government has already provided. Those capital boosts remain regardless of how the government shifts the maturity of its liabilities. So yes, bond markets love deficit spending and do not “punish” governments for doing it.

Regarding the irrelevance of the money multiplier I want to remind everybody that we owe credit to the Radcliffe Report for it as well as with its flexible definition of liquidity and endogenous velocity.

RSJ, something to chew on there.

I am unclear about this: it is completely up to the currency issuer to set call money rates and how they respond to any other variable in the economy. Do you mean through setting margin requirements or something else?

Tom,

By lending freely at rate X, that will put a ceiling on the call money rate. By imposing fees on lending (e.g. an “insurance fee” of X%/yr for every loan made) you can put a floor under the call money rate. The combination lets you control this rate fully — at least for regulated banks.

The point is, you know that the government has the power to be the marginal seller (supplying the asset to the market) and the marginal buyer (removing the asset from the market). So from first principles, you know that the government has the ability to set the price of the asset — cash — in the interbank market.

From those first principles, you pick your favorite mechanism of adding and draining. For example, imposing of fees on assets guarantees that the government is draining on the margin, and lending freely adds at the margin.

By the way, this is why, just from first principles, you know that paying interest on reserves will will fail to move yields in the Money Market in the same way that FF currently fails to move lending rates for banks whose liabilities are primarily core deposits. The current system allows governments to lose control of lending rates, as famously happened in Japan in 1989-1990.

As the vast majority of transactions net out in a reliable pattern, a bank will ignoring the reserve interest payment rate (or fee) in setting lending rates: If $1 lent imposes an expected reserve cost of 5 cents, then the rate or payment on that nickel is irrelevant.

What will affect the rate charged is your general cost of funds for the other 95 cents. If those liabilities, in the steady state, are Money Market liabilities, then the MM rate will determine your cost of funds. If those liabilities are core deposits, then your deposit rate will be your cost of funds.

That is why, when international banks began to charge Japanese banks a “Japan premium”, then the interbank lending rates in Japan rose far above the policy rate as set by the BOJ — Japanese banks held liabilities to foreign banks. In the same way, U.S. banks that are primarily funded by core deposits are unaffected by monetary policy rate hikes. Their overall cost of funds do not increase when the CB hikes rates. Fortunately, these banks are minor in terms of total assets within the overall banking system.

So a better system would be to impose fees directly on bank assets, ensuring that you are truly the marginal drainer. In that case you will be able to put a floor under bank cost of funds and will affect rates charged to borrowers in a reliable manner.

RSJ,

You seem to have only one theory: Interest rates depend on the growth rate of the economy. Anything else is wrong according to you! Just an observation.

NKlein1553 said: “A related question then: what are the reserves that quantitative easing adds to?”

I’m thinking the “reserves” you are referring to are central bank reserves. IMO and since the gov’t in the USA won’t let their dumb fed fail, central bank reserves are actually 1-day gov’t debt in disguise that can in some ways function like currency (but not as bank capital???).

NKlein1553 said: “When the Federal Reserve swaps currency for bonds, mortgage backed securities, and other various long term assets banks hold that are of dubious value does that extra currency count toward the capital banks must hold against projected losses? If so, wouldn’t that mean quantitative easing has the potential to increase the capacity of banks to make loans contrary to Professor Mitchell’s Quantitative Easing 101 post?”

Have you answered with one reason why the fed bought mortgage backed securities with central bank reserves instead of currency?

Why didn’t the banks convert all these “excess central bank reserves” into currency?

Nathan Tankus said:

“Fed Up says:

Thursday, February 25, 2010 at 18:03

Nathan Tankus, I would suggest personal finance of the lower and middle class. Specifically, that the lower and middle class can be suckered into believing expectations of price inflation, hourly wage inflation, and hours worked inflation that don’t turn out to be true to “trick” them into going into debt to the rich in the present so the rich can maintain their excess savings” decent suggestion; my train of thought has lead me somewhere different so bear with me. as time passes the average persons willingness to dissave (whether by spending past savings or taking out a loan) increases proportionally to asset prices increase and decreases proportionally as asset prices decrease.”

I think you need to find out whether and which groups are experiencing negative real earnings growth and positive real earnings growth.

“i am unsure how to make that a workable function or how to integrate it into a consistent stock flow model.”

The business cycle is hard to model???

what i meant more was for that model to work i need a complex consumption function where consumption increases as time passes and the economy accrues more asset price increases and decreases as asset prices decrease and a general credit crunch in the economy occurs. hey there are new keynesian people that basically create business cycle models by inputing “random events” into there neoclassical growth models. this may “model” the business cycle but it doesn’t tell us anything. i’m trying to figure out a way to catch up my mathmatical model to my verbal understandings. guess it’s time to hit the books…