The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 2

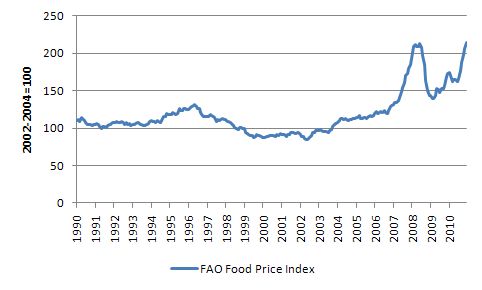

The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) released their monthly index of food prices yesterday (January 5, 2011) which showed that the index reached a record high in December 2010 “surpassing the levels of 2008 when the cost of food sparked riots around the world, and prompting warnings of prices being in “danger territory”” (Source). There are several reasons why food prices will move even higher – the catastrophic floods in Northern Queensland being among them. The rising food prices are once again leading to calls for interest rates to rise in order to minimise the inflationary consequences. That motivated me to write Part 2 of my series on inflation – in this case supply-side motivated inflations. In Part 1 of the series – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1 – I concentrated on demand-side origins.

In their recently released 2010 Report – The State of Food Insecurity in the World – the FAO estimated that:

After increasing from 2006 to 2009 due to high food prices and the global economic crisis, both the number and proportion of hungry people have declined in 2010 as the global economy recovers and food prices remain below their peak levels. But hunger remains higher than before the crises …

The following graph shows the FAO Food Price Index up to December 2010 (from January 1990).

Why is that graph important? Because the rising food prices will reverse the recent trends which saw a modest decline in the number of undernourished people in the world in the last year as a result of falling prices since 2008 (due mostly to the recession). All the analysis in the FAO report – which is mildly positive in terms of trends – is predicated on the drop in food prices that accompanied the recession and some good harvests in developing nations. I expect that positive slant will not be realised in practice and that hunger will rise in the coming year.

Further, in the detailed report you will find nothing to support the view that people are poor because governments have run budget deficits. In fact, the opposite would be suggested given the importance of providing quality education, health care and public infrastructure.

One set of facts which should always be borne in mind when considering whether current neo-liberal policy approaches are working is that in developed countries there were 13 per cent of the total population undernourished (2005-07) whereas in developing countries this proportion was 16 per cent. In other words, the “wealthy” world is not all that much better at feeding its poor.

Anyway, back to the main theme.

In the UK Guardian article (January 5, 2011) – Inflation threat divides economists – we read that so-called experts are “split on question of whether surge in oil and food prices will result in higher inflation and interest rates”.

The optimists (those who do not think there will be an inflationary threat) point to the possible ephemeral nature of the rising food prices and the recent “pick-up in oil prices”.

The consumer price indexes that central banks tend to use trim out ephemeral price rises to bring out underlying price movements.

I am less optimistic given the energy demand from the growing Indian and Chinese economies. I last conjectured on that issue in this blog – Be careful what we wish for ….

The head of the UK National Institute for Economic and Social Research told the Guardian that rising energy demand from Asia could “trigger a sustained rise in inflation that would need to be quelled by higher interest rates”. They also quoted one of UK’s extreme monetarists (still pushing that line) who considered the low interest rates in the UK in response to the crisis to be a “dangerous nonchalance”. He is just rehearsing his recurring theme and the informational content of that theme is low.

The Guardian article then presented the opposite case which I found interesting:

Some economists argue we must forget about raising interest rates and live with higher inflation imported from China and the east. If UK inflation were the result of excess demand in the UK then higher base rates could usefully dampen consumption and moderate inflation. If inflationary prices are driven by excess demand in the east or shortages in Australian wheat – factors beyond the control of UK policymakers – then why choke off our nascent economic revival with higher rates, they say.

So the tension in the policy debate is whether to deal with a supply-side price surge (if it turns out to be significant) via demand-side policies (tightening interest rates and fiscal austerity). Fiscal austerity in this context is considered essential by those who believe in the primacy of monetary policy for discipling the inflation process rather than in the current sense that public debt levels are too high.

The reference to Australian floods is also not insignificant. The following pictures shows two NASA satellite images of the area in Northern Queensland around Rockhampton where the floods are very bad at present. The top image was taken on January 4, 2011 while the bottom (of the same area) was taken on December 14, 2010. They allow you to gauge how bad the situation is – this is a very big land area.

You can see more images and analysis HERE.

While the human and social elements of the floods will be very significant, economists have focused on their impact on real GDP growth and inflation – and given the current neo-liberal mindset – monetary policy.

Economists have predicted that the floods in Queensland that are now – courtesy of south-flowing rivers heading to my state (NSW). The Sydney Morning Herald article – Economists warn of dire short-term repercussions (January 6, 2011) said the floods are:

… expected to ravage the Australian economy this year by hitting growth and driving up inflation … coal exports worth $100 million a day were being lost or postponed due to the floods … [economists] … expected the crisis to wipe about 0.3 per cent off gross domestic product immediately … prices were expected to rise because of the effect on agriculture … [there would be a] … 0.75 per cent rise in inflation …

The growth impact should only be temporary because the public spending involved in the rebuilding (supplemented by the insurance payouts if the insurance companies play if fairly and unlike other crises try to short-change their policy holders with all sorts of loopholes and technicalities) will stimulate demand and hence economic activity.

The disruption to coal mining (many mines are flooded or closed because of drainage issues) will also impact on world coal prices given that “Queensland supplies almost a quarter of the world’s seaborne coal exports, and about half of all exports of coking coal”.

So the public discussion about the floods among economists has now turned to its “inflationary” impact. Energy prices are already rising and food prices will definitely rise over the next few months given that the flooded area is a very significant supplier of many vegetable lines (especially in Winter as the southern farms move to cooler crops).

The most asinine comment I heard yesterday was from our Prime Minister who said that while the Federal Government was going to provide as much fiscal support to the flood-affected communities and businesses they would have to make “savings” elsewhere to make sure they kept true to their pledge to get the budget back into surplus next year.

She clearly hasn’t been briefed by her advisers that if the expected loss of real output (growth declines) then the budget will be heading in the opposite direction courtesy of the automatic stabilisers (falling tax revenue, increased welfare outlays) and she won’t have a hope in hell of getting the budget into surplus.

The deeper question is why should they target a surplus at this point in the business cycle anyway given that we have at least 12.5 per cent of our willing labour resources remaining idle (unemployed or underemployed) and even a higher number outside the labour force who want to work. That is another question which I will address in another blog another day.

Economists were being wheeled out by the media in the last 24 hours and many were arguing that interest rates would have to rise to combat the inflationary impact.

So they were advocating a supply-side event which generates costs pressures being dealt with through a demand-side measure (which intends to squeeze purchasing power and reduce aggregate demand).

Supply-side inflation

In this blog – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1 – I outlined what the demand-side theory of inflation.

Economists distinguish between cost-push and demand-pull inflation although the demarcation between the two “states” is not as clear as one might think. This is a good site for background material.

Demand-pull inflation refers to the situation where prices start accelerating continuously because nominal aggregate demand growth outstrip the capacity of the economy to respond by expanding real output. Remember Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the market value of final goods and services produced in some period.

So GDP = P.Y where P is the aggregate price level and Y is real output. Aggregate demand (expenditure) is always equal (by national accounting) to GDP or P.Y. So if there is growth in demand that cannot be met by growth in Y then P has to rise.

Keynes outlined the notion of an inflationary gap in his famous article – J.M. Keynes (1940) How to Pay for the War: A radical plan for the Chancellor of the Exchequer. London: Macmillan.

While this was in the context of war-time spending when faced by tight supply constraints (that is, an restricted ability to expand real output), the concept of the inflationary gap has been generalised to describe situations of excess demand (which I outlined above).

When there is excess capacity (supply potential) rising nominal aggregate demand growth will typically impact on real output growth first as firms fight for market share and access idle labour resources and unused capacity without facing rising input costs. As the economy nears full capacity the mix between real output growth and price rises becomes more likely to be biased toward price rises (depending on bottlenecks in specific areas of productive activity). At full capacity, GDP can only grow via inflation (that is, nominal values increase only).

Cost-push inflation (sometimes called “sellers inflation”) has a long tradition in the progressive literature (Marx, Kalecki, Lerner, Kaldor, Weintraub) although it is not exclusively a progressive theory. Milton Friedman considered that wage demands from trade unions were a major threat to inflation although he ultimately considered central bank monetary policy to be the real problem in that they accommodated these wage demands by increasing the “money supply”.

Cost-push inflation is an easy concept to understand and is generally explained in the context of “product markets” (where goods a sold) where firms have price setting power. That is, the perfectly competitive model that pervades the mainstream economics textbooks where firms have no market power and take the price set in the market, is abandoned and instead firms set prices by applying some form of profit mark-up to costs.

Kalecki is notable in that he started his analysis assuming mark-up pricing as an attempt to develop economic theory that was based on how the real world actually operated.

The notion is pretty straightforward although there are many different versions. But generally, firms are considered to have target profit rates which they render operational by the mark-up on unit costs. Unit costs are driven largely by wage costs, productivity movements and raw material prices.

Trade union bargaining power was considered an important component of the capacity of workers to realise nominal wage gains and this power was considered to be pro-cyclical – that is, when the economy is operating at “high pressure” (high levels of capacity utilisation) workers are more able to succeed in gaining money wage gains.

In these models, unemployment is seen as disciplining the capacity of workers to gain wages growth – in line with Marx’s reserve army of unemployed idea.

Workers have various motivations depending on the theory but most accept that real wages growth (increasing the capacity of the nominal or money wage to command real goods and services) is a primary aim of most wage bargaining.

So we get a “battle of the mark-ups” operating – workers try to get more real output for themselves by pushing for higher money wages and firms then resist the squeeze on their profits by passing on the rising cost – that is, increasing prices with the mark-up constant.

At that point there is no inflation – just a once-off rise in prices and no change to the distribution of national income in real terms.

However, if the economy is working at high pressure, workers may resist the attempt by capital to keep their real wage constant (or falling) and hence they may respond to the increasing prices by making further nominal wage demands. If their bargaining power is strong (which from the firm’s perspective is usually in terms of how much damage the workers can inflict via industrial action on output and hence profits) then they are likely to be successful.

At that point there is still no inflation. But if firms are not willing to absorb the squeeze on their real output claims then they will raise prices again and the beginnings of a wage-price spiral begins. If this process continues then you have a cost-push inflation.

The causality may come from firms pushing for a higher mark-up and trying to squeeze workers’ real wages. In this case, we might refer to the unfolding inflationary process as a price-wage spiral.

Conflict theory of inflation

There was a series of articles in Marxism Today in 1974 which advanced the notion of inflation being the result of a distributional conflict between workers and capital. One such article by Pat Devine (1974) ‘Inflation and Marxist Theory’, Marxism Today, March, 70-92 is worth reading if you can find it. As an aside, you can view an limited archive of Marxism Today since 1977 which is a very valuable resource.

Another influential book at the time was Robert Rowthorn’s 1980 book – Capitalism, Conflict and Inflation (Lawrence and Wishart).

The conflict theory derives directly from cost-push theories referred to above. Conflict theory recognises that the money supply is endogenous (as opposed to the Monetarist’s Quantity Theory of Money which assumes, wrongly, that the money supply is fixed).

In this world, firms and unions have some degree of market power (that is, they can influences prices and wage outcomes) without much correspondence to the state of the economy. They both desire some targetted real output share.

In each period, the economy produces a given real output which is shared between the groups with distributional claims. If the desired real shares of the workers and bosses is consistent with the available real output produced then there is no incompatibility and there will be no inflationary pressures.

But when the sum of the distributional claims (expressed in nominal terms – money wage demands and mark-ups) are greater than the real output available then inflation can occurs via the wage-price or price-wage spiral noted above.

The wage-price spiral might also become a wage-wage-price spiral as one section of the workforce seeks to restore relativities after another group of workers succeed in their wage demands.

That is, the conflict over available real output promotes inflation. Various dimensions can then be studied – the extent to which different wage contracts overlap and are adjusted, the rate of growth of productivity (which provides “room” for the wage demands to be accomodated without squeezing the profit margin), the state of capacity utilisation (which disciplines the capacity of the firms to pass on increasing costs), the rate of unemployment (which disciplines the capacity of workers to push for nominal wages growth).

Now here is the complication. Conflict theories of inflation note that for this distributional conflict to become a full-blown inflation the central bank has to ultimately “accommodate” the conflict. What does that mean?

If the central bank pushes up interest rates and makes credit more expensive, firms will be less able to pay the higher money wages (the conceptualisation is that firms access credit to “finance” their working capital needs in advance of realisation via sales). Production becomes more difficult and workers (in weaker bargaining positions) are laid off.

The rising unemployment, in turn, eventually discourages the workers from pursuing their on-going demand for wage increases and ultimately the inflationary process is choked off.

However, if the central bank doesn’t tighten monetary policy and the fiscal authorities do not increase taxes or cut public spending then the incompatible distributional claims will play out and inflation becomes inevitable.

Note I have not considered in any detail in this blog – the open economy interpretations of the conflict theory of inflation which have been developed by several Latin American researchers. That will be in Part 3 in this series which I will write another day.

There are also strong alignments between the conflict theory of inflation and Minksy’s financial instability notion. Both consider the dynamics are variable across the business cycle and so when economic activity is weak, both the distributional claims and the attitude of banks to lending will be benign. As the economic growth gathers pace, the claims increase and the risk-averseness of banks declines and more risky loans are made.

Pat Devine’s article (noted above) also introduced the notion that inflation was a structural construct. He argued that the increased bargaining power of workers (that accompanied the long period of full employment in the Post Second World War period) and the declining productivity in the early 1970s imparted a structural bias towards inflation which manifested in the inflation breakout in the mid-1970s which he says “ended the golden age”.

This notion implicates Keynesian-style approaches to full employment – and says the conduct of fiscal policy which squarely aimed to maintain full employment and high growth rates provided the structure for the biases to emerge. Then with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of convertible currencies and fixed exchange rates (which provided deflationary forces to economies that had strongly domestic demand growth) these structural biases came to the fore.

Rowthorn says that the mid-1970s crisis – which marked the end of the Keynesian period and the start of the neo-liberal period – was associated with a rising inflation but also an on-going profit squeeze due to declining productivity and increasing external competition for market share. The profit squeeze led to firms reducing their rate of investment (which reduced aggregate demand growth) which combined with harsh contractions in monetary and fiscal policy created the stagflation that bedeviled the world in the second half of the 1970s.

The resolution to the “structural bias” was the policy-motivated attack on the working class bargaining power – both in the form of the persistently high unemployment and specific labour relations legislation. The subsequent redistribution of real income towards profits reduced the inflation spiral as workers were unable to pursue real wages growth and productivity growth outstripped real wages growth.

In one of my early articles (1987) – in the Australian Economic Papers – The NAIRU, Structural Imbalance and the Macroequilibrium Unemployment Rate – I developed the notion of a macroequilibrium unemployment rate. This came from my PhD research on inflation and natural rates. It was the first Australian study of hysteresis and one of the first international studies.

The motivation was clearly that the policy orientation in the UK, the US and in Australia was and remains based on the view that inflation is the basic constraint on expansion (and fuller employment).

The popular belief is that fiscal and monetary policy can no longer attain unemployment rates common in the sixties without ever-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. The natural rate of unemployment (NRU) which is the rate of unemployment consistent with stable inflation is considered to have risen over time.

The non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is a less rigorous version of the NRU but concurs that a particular, cyclically stable unemployment rate coincides with stable inflation. Labour force compositional changes, government welfare payments, trade-union wage goals among other “structural” influences were all implicated in the rising estimates of the inflationary constraint.

The NAIRU achieved such rapid status among the profession as a policy-conditioning concept that I thought it warranted close scrutiny.

My basic proposition was that persistently weak aggregate demand creates a labour market, which mimics features conventionally associated with structural problems.

The specific hypothesis I examined was whether the equilibrium unemployment rate is a direct function of the actual unemployment rate and hence the business cycle. That is the hysteresis effect.

By developing an understanding of the way the labour market adjusts to swings in aggregate demand and generates hysteresis, providing a strong conceptual and empirical basis for advocating counter-stabilising fiscal policy (aggregate policy expansion in a downturn).

So while it might look like the degree of slack necessary to control inflation may have increased, the underlying cyclical labour market processes that are at work in a downturn can be exploited by appropriate demand policies to reduce the steady state unemployment rate.

In that work I outlined a conceptual unemployment rate, which is associated with price stability, in that it temporarily constrains the wage demands of the employed and balances the competing distributional claims on output.

I introduced a new term the macroequilibrium unemployment rate (the MRU) which I noted was, importantly, sensitive to the cycle due to the impact of the cyclical labour market adjustments on the ability of the employed to achieve their wage demands. In this sense, the MRU is distinguished from the conventional steady state unemployment rate, the NAIRU, which is not conceived to be cyclically variable.

What I wanted to show was that there was an interaction between the actual and MRU which would establish the presence of the hysteresis effect.

To be clear – the significance of hysteresis, if it exists, is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy.

The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate. That is why I chose to use the term MRU, as the non-inflationary unemployment rate, as distinct from the NAIRU, to highlight the hysteresis mechanism.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

So why would there be some unemployment rate that is consistent with stable inflation. Remember this is a non Job Guarantee world. The introduction of a JG would change things considerably (more favourably).

There is an extensive literature that links the concept of structural imbalance to wage and price inflation. A non-inflationary unemployment rate can be defined which is sensitive to the cycle.

My work at the time was contributing to the view that inflation was the product of incompatible distributional claims on available income. So when nominal aggregate demand is growing too quickly, something has to give in real terms for that spending growth to be compatible with the real capacity of the economy to absorb the spending.

Unemployment can temporarily balance the conflicting demands of labour and capital by disciplining the aspirations of labour so that they are compatible with the profitability requirements of capital. That was Kalecki’s argument which I considered in the blog – Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment.

A lull in the wage-price spiral could thus be termed a macroequilibrium state in the limited sense that inflation is stable. The implied unemployment rate under this concept of inflation is termed in this paper the MRU and has no connotations of voluntary maximising individual behaviour which underpins the NAIRU concept that is at the core of mainstream macroeconomics.

Wage demands are thus inversely related to the actual number of unemployed who are potential substitutes for those currently employed.

Increasing structural imbalance (via cyclical non-wage labour market adjustment) drives a wedge between potential and actual excess labour supply, and to some degree, insulates the wage demands of the employed from the cycle. The more rapid the cyclical adjustment, the higher is the unemployment rate associated with price stability.

Stimulating job growth can decrease the wedge because the unemployed develop new and relevant skills and experience. These upgrading effects provide an opportunity for real growth to occur as the cycle reduces the MRU.

Why will firms employ those without skills? An important reason is that hiring standards drop as the upturn begins. Rather than disturb wage structures firms offer entry-level jobs as training positions.

It is difficult to associate wage demands (in excess of current money wages) with the workforce. While the increased training opportunities increase the threat to those who were insulated in the recession this is offset to some degree by the reduced probability of becoming unemployed.

The subsequent empirical work I did and which has since been built on by others has blown the NAIRU concept out of the water. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

At the time, and since, a lot of progressives have objected to the idea that there is some steady-state unemployment rate that disciplines inflation. They claim is sounds like a NAIRU and is a concession to the mainstream paradigm.

Rowthorn clearly understood that at some level of unemployment – which emerges when the government tightens its policy settings – inflation stabilises. This sounds like a NAIRU.

In my 1987 article I wrote:

Inflation results from incompatible distributional claims on available income, unemployment can temporarily balance the conflicting demands of labour and capital by disciplining the aspirations of labour so that they are compatible with the profitability requirements of capital … The wage-price spiral lull could be termed a macroequilibrium state in the limited sense that inflation is stable. The implied unemployment rate under this concept of inflation is termed in this paper the MRU and has no connotations of voluntary maximising individual behaviour which underpins the NAIRU concept …

That is a crucial distinction – it is no surprise in a capitalist system that if you create enough unemployment you will suppress wage demands given that workers, by definition, have to work to live.

But you can underpin this notion of equilibrium without recourse to the individualistic and optimising behaviour assumed by the mainstream.

Raw material price rises

Raw material shocks can also trigger of a cost-push inflation. They can be imported or domestically-sourced. I will devote a special blog to imported raw material shocks in the future.

But the essence is that an imported resource price shock amounts to a loss of real income for the nation in question. This can have significant distributional implications (as the OPEC oil price shocks in the 1970s had). How the government handles such a shock is critical.

The dynamic is that the imported resources reduces the real income that is available for distribution domestically. Something has to give. The loss has to be shared or borne by one of the claimants or another. If the workers resist the lower real wages or if bosses do not accept that some squeeze on their profit margin is inevitable then a wage-price/price-wage spiral can emerge.

The government can employ a number of strategies when faced with this dynamic. It can maintain the existing nominal demand growth which would be very likely to reinforce the spiral.

Alternatively, it can use a combination of strategies to discipline the inflation process including the tightening of fiscal and monetary policy to create unemployment (the NAIRU strategy); the development of consensual incomes policies and/or the imposition of wage-price guidelines (without consensus).

Progressives argued that the best way to deal with such the likelihood is via an incomes policy saying that the NAIRU strategy is very costly in terms of real output losses.

They consider incomes policies can be developed with mediate the claims on the real income available to render them compatible over time. I will write a separate blog about incomes policies as I did a lot of work on them in the late 1980s and into the 1990s.

I also wrote some papers in the 1980s on having wage-price rules driven by productivity growth in certain sectors (for example, in the so-called Scandinavian Model (SM) of inflation.

This model, originally developed for fixed exchange rates, dichotomises the economy into a competitive sector (C-sector) and a sheltered sector (S-sector). The C-sector produces products, which are traded on world markets, and its prices follow the general movements in world prices. The C-sector serves as the leader in wage settlements. The S-sector does not trade its goods externally.

Under fixed exchange rates, the C-sector maintains price competitiveness if the growth in money wages in its sector is equal to the rate of change in its labour productivity (assumed to be superior to S-sector productivity) plus the growth in prices of foreign goods. Price inflation in the C-sector is equal to the foreign inflation rate if the above rule is applied. The wage norm established in the C-sector spills over into wages growth throughout the economy.

The S-sector inflation rate thus equals the wage norm less its own productivity growth rate. Hence, aggregate price inflation is equal to the world inflation rate plus the difference between the productivity growth rates in the C- and S-sectors weighted by the S-sector share in total output. The domestic inflation rate can be higher than the rate of growth in foreign prices without damaging competitiveness, as long as the rate of C-sector inflation is less than or equal to the world inflation rate.

In equilibrium, nominal labour costs in the C-sector will grow at a rate equal to the room (the sum of the growth in world prices and the C-sector productivity). Where non-wage costs are positive (taxes, social security and other benefits extracted from the employers), nominal wages would have to grow at a lower rate. The long-run tendency is for nominal wages to absorb the room provided. However in the short-run, labour costs can diverge from the permitted growth path. This disequilibrium must emanate from domestic factors.

The main features of the SM can be summarised as follows:

- The domestic currency price of C-sector output is exogenously determined by world market prices and the exchange rate.

- The surplus available for distribution between profits and wages in the C-sector is thus determined by the world inflation rate, the exchange rate and the productivity performance of industries in the C-sector.

- The wage outcome in the C-sector is spread to the S-sector industries either by design (solidarity) or through competition.

- The price of output in the S-sector is determined (usually by a mark-up) by the unit labour costs in that sector. The wage outcome in the C-sector and the productivity performance in the S-sector determine unit labour costs.

An incomes policy would establish wage guidelines which would set national wages growth according to trends in world prices (adjusted for exchange rate changes) and productivity in the C-sector. This would help to maintain a stable level of profits in the C-sector.

Whether this was an equilibrium level depends on the distribution of factor shares prevailing at the time the guidelines were first applied.

Clearly, the outcomes could be different from those suggested by the model if a short-run adjustment in factor shares was required. Once a normal share of profits was achieved the guidelines could be enforced to maintain this distribution.

A major criticism of the SM as a general theory of inflation is that it ignores the demand side. Uncoordinated collective bargaining and/or significant growth in non-wage components of labour costs may push costs above the permitted path. Where domestic pressures create divergences from the equilibrium path of nominal wage and costs there is some rationale for pursuing a consensus based incomes policy.

An incomes policy, by minimising domestic cost fluctuations faced by the exposed sector, could reduce the possibility of a C-sector profit squeeze, help maintain C-sector competitiveness, and avoid employment losses. Significant contributions to the general cost level and hence prices can originate from the actions by government. Payroll taxation, various government charges and the like may in fact be more detrimental to the exposed sector than increased wage demands from the labour market.

Although the SM was originally developed for fixed exchange rates, it can accommodate flexible exchange rates. Exchange rate movements can compensate for world price changes and local price rises. The domestic price level can be completely insulated from the world inflation rate if the exchange rate continuously appreciates (at a rate equal to the sum of the world inflation rate and C-sector productivity growth).

Similarly, if local price rises occur, a stable domestic inflation rate can still be maintained if a corresponding decrease in C-sector prices occur. An appreciating exchange rate discounts the foreign price in domestic currency terms.

What about terms of trade changes? Terms of trade changes, which in the SM justify wage rises, also (in practice) stimulate sympathetic exchange rate changes. This combination locks the economy into an uncompetitive bind because of the relative fixity of nominal wages. Unless the exchange rate depreciates far enough to offset both the price fall and the wage rise, profitability in the C-sector will be squeezed.

It was considered appropriate to ameliorate this problem through an incomes policy. Such a policy could be designed to prevent the destabilising wage movements, which respond to terms of trade improvements. In other words, wage bargaining, consistent with the mechanisms defined by the SM may be detrimental to both the domestic inflation target and the competitiveness of the C-sector, and may need to be supplemented by a formal incomes policy to restore or retain consistency.

I remind all progressives of what Rowthorn (a Marxist economist) noted:

…trade unions cannot afford to be too successful …

Which means in a capitalist system which is driven by the rate of profit, workers can create unemployment by being tpo successful in their wage demands.

Modern Monetary Theory policy considerations

As I explained in Part 1 of this series – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1 – a cost-push inflation requires certain aggregate demand conditions to continue for its fuel. In this regard, the concept of a supply-side inflation blurs with the demand-pull inflation although their originating forces might be quite different.

An imported raw material shock just means that real income is lower and will not cause inflation unless it triggers an on-going distributional conflict. That conflict needs “oxygen” in the form of on-going economic activity in sectors where the spiral is robust.

The preferred approach is to use employment buffer stocks in conjunction with fiscal policy adjustments to allow the available real income to be rendered compatible with the existing claims.

Modern Monetary Theory rejects the NAIRU approach (the current orthodoxy) – that is, the use of unemployment buffer stocks – where inflation is controlled using tight monetary and fiscal policy, which leads to a buffer stock of unemployment. This is a very costly and unreliable target for policy makers to pursue as a means for inflation proofing.

Employment buffer stocks rests on the government exploiting its fiscal power that is embodied in a fiat-currency issuing national government to introduce full employment based on an employment buffer stock approach. The Job Guarantee (JG) model which is central to MMT is an example of an employment buffer stock policy approach.

Under a Job Guarantee, the inflation anchor is provided in the form of a fixed wage (price) employment guarantee.

Full employment requires that there are enough jobs created in the economy to absorb the available labour supply. Focusing on some politically acceptable (though perhaps high) unemployment rate is incompatible with sustained full employment.

In MMT, a superior use of the labour slack necessary to generate price stability is to implement an employment program for the otherwise unemployed as an activity floor in the real sector, which both anchors the general price level to the price of employed labour of this (currently unemployed) buffer and can produce useful output with positive supply side effects.

The employment buffer stock approach (the JG) exploits the imperfect competition introduced by fiat (flexible exchange rate) currency which provides the issuing government with pricing power and frees it of nominal financial constraints.

The JG approach represents a break in paradigm from both traditional Keynesian policies and the NAIRU-buffer stock approach. The difference is a shift from what can be categorised as spending on a quantity rule to spending on a price rule.

I noted interest in this concept today among the comments and I will write more about it in due course. But the point is that under a spending rule (which is the current policy approach), the government budgets a quantity of dollars to be spent at prevailing market prices.

In contrast, under a price rule (the JG option) the government offers a fixed wage to anyone willing and able to work, and thereby lets market forces determine the total quantity of government spending. This is what I call spending based on a price rule.

How does the government decide that net public spending is just right? Answer: the JG is an automatic stabiliser. The last worker that comes into the JG office to accept a wage tells you the limits of the program and the size of the budget commitment.

This becomes more complicated when there are other programs being offered. But given the automatic stabiliser nature of the JG, the government at least knows exactly how much it has to outlay each period to maintain (loose) full employment. What is does in addition to this depends on its policy ambitions and the degree of excess capacity in the non-JG sectors of the economy.

Many economists who are sympathetic to the goals of full employment are sceptical of the JG approach because they fear it will make inflation impossible to control.

However, if the government is buying a resource with zero market bid (the JG workers) and moving resources from the inflating sectors to the fixed price sector then inflation control is possible – no matter the origin.

Some people have argued that the JG could be offered in conjunction with an incomes policy if the implied JG-pool that is required to resolve the inflation spiral is too large.

This is entirely possible if you can devise an effective incomes policy. It is unnecessary for inflation control once the JG is in place but could reduce the size of the shift in resources between the private economy and the JG pool should that be considered problematic.

Conclusion

My main concern about the rising prices at present that are of supply-side origin relate to the FAO issues raised at the outset. The number (and proportion) of people in hunger will rise and that should be a government policy priority.

It certainly will not be a priority as long as governments continue headlong into fiscal austerity.

Further, under current policy approaches based on the NAIRU, if the central banks use demand-side policies to deal with a supply-side motivated problem the costs will be very high. The only way that demand-side policies should be used to effect when there is a supply-side motivated inflation is when there is an employment buffer stock system in place.

Total aside – be careful when builders are around

We are currently getting some work done on our house to make it more functional. So walls are getting torn down and all that sort of thing. When I get home at night I am interested in seeing the progress and so far so good.

Not so for one person in Pittsburgh – see story.

So next time there are builders in your street make sure your house is either scheduled for work or someone else’s is!

That is (more) than enough for today!

Great post Bill, but I think my brain developed an out of memory error half way through. I’ll have to read it again once the garbage collection routine has completed.

🙂

Deep stuff.

Bill, that’s a really interesting follow up to your first inflation post, thanks. There is so much in there to think about.

Regarding your final comments about the JG and inflation control, I have a couple of questions.

1) I understand the concept of the buffer stock of employment replacing a buffer stock of unemployment as a means of inflation control. So rather than move from employment to unemployment, people move from employment in a non-JG job to employment in a JG job. But I still don’t understand how the govt/central bank effects this transition. In the current system, the CB increases interest rates, activity slows, unemployment (or the possibility of it) goes up, inflation cools. But you advocate a 0% policy, so the tightening must be fiscal. How would this work exactly?

2) Also, how does the govt determine the “right” proportion of JG workers to non-JG workers. For example the country could be at full employment with 98% non-JG / 2% JG mixture, or 70% non-JG / 30% JG mixture. These would be very different economies. As the JG is by definition a minimum wage position, I would guess that the more people with non-JG jobs the better. So what is the measure that the govt can use to determine if they have “room” to stimulate (cut taxes or increase spending) which would draw people away from the JG into non-JG jobs? The rate of inflation?

Bill,

Is it possible inflation and unemployment have no relation at all? High levels of emploment mean more goods/services are being produced and owners of proction will take more aggressive actions to increase productivity to keep labor cost down while labor supplies are tight. And when unemployment is high, welfare payments will allow for consumption without production and owners may find it cheaper to higher labor than to increase productivity. Both would suggest an inverse relationship between employment and inflation. I know this is just intuition and not based on in depth economic analysis, models, formulas, etc. But the late 70s had high inflation and high unemployment, while the late 90s had low unemployment and low inflation. Look what is happening now, high unemployment with energy and food prices moving higher.

Bill, Your section “Conflict Theory of Inflation” above certainly contains an element of truth. But there are counter arguments. E.g. on the subject of hysteresis there are two studies which claim hysteresis is not significant (1 & 2 below).

Re skills, several studies have been done in Europe which show that the sort of training associated with JG type schemes (or offered as alternative to JG type schemes) does NOT improve subsequent employment chances. (Straightforward subsidised work is better.)

There is also a fundamental conflict between the requrements of training schemes of JG type work, as follows. People doing the latter type of work MUST be available for jobs else aggregate labour supply is reduced, which could be inflationary. On the other hand training courses almost invariable last a SPECIFIC length of time. Look at schools, universities, etc: there is no other way of organising training or education.

Conclusion: this is a difficult and complicated area!

1. http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/cjeconf/delegates/webster.pdf

2. Goldstein, H., Knut, R. and Oddbjorn, R. (1999) “Does Unemployment cause Unemployment?” Applied Economics Vol 31 No 10 pp 1207 – 18.

Hi, Bill-

Could I plead with you to be more succinct? This post was both abstruse, involving many barely articulated concepts, and very broad, ranging over several historical models of inflation and other issues.. you are taxing your (lay) readers in the extreme. At ~7000 words, it was about 28 pages worth of typical book material, or two chapters. But we appreciate your work!

“The preferred approach is to use employment buffer stocks in conjunction with fiscal policy adjustments to allow the available real income to be rendered compatible with the existing claims.”

To be brief, it seems that in your scheme, an army of the marginally employed and marginally paid replaces the army of the unemployed and unpaid which exists now to discipline wage demands and inflation. To a naive observer, wouldn’t an equal effectiveness require a larger army of the former than of the latter? Certainly a great deal of suffering would be averted, but wouldn’t one result be a net leveling-down of worker incomes? I guess the core argument is that if the army of marginally employed actually accomplish something and also bolster their productivity over the long term, everyone is better off. But still the question of the prospective size of the JG pool seems significant.

Gamma @ 22:14: In the current system, the CB increases interest rates, activity slows, unemployment (or the possibility of it) goes up, inflation cools.

In theory, but not in practice. Interest rates are a blunt instrument and have proven rather ineffective, as we are now seeing. Moreover, it is not necessary to create a recession to stem inflation. That’s essentially what interest rate manipulation does historically.

But you advocate a 0% policy, so the tightening must be fiscal. How would this work exactly?

Taxation withdraws nongovernment net financial assets, decreasing nominal aggregate demand. (See Abba Lerner’s principles of functional finance.)

Also, how does the govt determine the “right” proportion of JG workers to non-JG workers.

Government doesn’t; private sector demand for labor does. Government just stand ready to hire anyone willing to work that can’t find employment elsewhere. Since the JG wage is the floor wage, it is not competing against the private sector. One way to handle this is set the JG floor wage beneath the legal minimum wage for the private sector.

Uh, Burk, I think that the idea is that one is supposed to study these posts. This is Bill’s course in macro – for free. 🙂

Tom Hickey,

You said the private sector demand for labor determines the size of the JG. That may be true, but it is the govt that can determine the private sector demand for labor. If taxes are too high it can cause private sector aggregate demand to fall short of employing all labor. It is a loop that only govt fiscal policy can change. So Gamma\’s question is valid, what is the level of JG that MMT desires?

Tom,

Taxation withdraws nongovernment net financial assets, decreasing nominal aggregate demand. (See Abba Lerner’s principles of functional finance.)

Of course, my question is how exactly? Do you increase income tax rates, lower the tax thresholds, increase consumption tax rate?

Government doesn’t; private sector demand for labor does. Government just stand ready to hire anyone willing to work that can’t find employment elsewhere. Since the JG wage is the floor wage, it is not competing against the private sector. One way to handle this is set the JG floor wage beneath the legal minimum wage for the private sector.

Have a think about this again. You’re claiming that the govt can’t affect the level of employment in either the non-JG public sector or the private sector. That’s absurd. They can directly hire people to non-JG govt jobs or they can spend money on programmes which contributes to aggregate demand and will tend to draw people from JG jobs to non-JG jobs.

Tom, with all respect, have you noticed that I have posted here before, quite of few times? I have read much of Bill’s stuff, including this piece. I’m well aware of the basic concepts, you don’t need to reply to a specific question with general motherhood statements.

Cheers.

Bill, I don’t understand how the JG is supposed to “anchor” the price level. Elsewhere, you mention the use of monetary and fiscal policy to combat inflation, which would be unnecessary if the JG really was a price anchor.

On the other hand, we are using monetary and fiscal policy to combat inflation now even without a JG.

So what is the role of the JG vis-a-vis inflation?

The way I understand it is that the government is not promoting the JG any more actively than government promotes unemployment assistance. These are “passive” programs the purpose of which is respond to changing economic conditions, not programs that government actively promotes to provide employment, in competition with the private sector, for instance.

The purpose of the JG is two fold. First, its purpose lies in its purpose of setting an price anchor in the effort to replace the present monetary-based practice of targeting inflation using a buffer stock of unemployment as a tool. What government does actively through MMT is fiscal, by way of functional finance. Depending on how government uses functional finance to achieve optimal capacity utilization, full employment and price stability, the JG buffer stock of employed will expand or contract accordingly. Secondly, the JG reduces the cost to the economy, to the society and to individuals that results from unemployment.

Wm. Mitchell & Martin Watts, ““A Comparison Of The Macroeconomic Consequences Of Basic Income And Job Guarantee Schemes,” Vol. 2, Fall 2005, No.1, p. 14

Bill Said “Inflation results from incompatible distributional claims on available income.”

Can someone explain this in plain terms for me? I have read all Bill’s posts on inflation and 99% is understandable but the above language is outside my day to day experience.

In any case when it comes to inflation in Australia we have a Reserve Bank of Australia that is only focused on taming inflation and wage demands by puting up interest rates.

Big business is so big and profitable now they should have their own pool of unemployed in training as a reserve pool instead of bleating about skills shortages for the past 5 years. If they had invested in a training pool each year for 5 years they would now have a steady stream of skilled workers joining their workforce. This in turn would keep wages claims to manageable levels. Big business should be able to contract with an unemployed or under-skilled person to train them over a number of years in return for a minimum fixed period of employment of about 5 to 7 years. The Military do it so why not similar contracts for big business?

Gamma, sorry if I came across as preachy. I was summarizing a position for those who may not be familiar with it, assuming that many people look at the comments, and some are not up on the context.

We know that the basic idea of functional finance is withdrawing nongovernment NFA with taxation to address inflation. We also know that targeting taxes differently produces different results in different time frames. There is some debate about how best to do this.

This is not my bailiwick, but I have formed some opinions on taxation. As general principle, I would recommend taxing economic rent (land rent, monopoly rent, and financial rent) instead of taxing either income or production investment. If a government has a handle on fiscal policy it should be able to target taxation to incentive productive investment/income and disincentivize rent-seeking to minimize swings.

But it may be necessary to increase other taxes at times to stem inflation by directly addressing consumption through income or consumption taxes. Then is a matter of multipliers and time frame.

Punchy: Bill Said “Inflation results from incompatible distributional claims on available income.”

Say there are five things and five tokens equally divided among holders. Then given equal effective demand the price would be 1 token.

Increase everyone’s tokens by 1 so everyone has 2. Now the price goes to 2. The price is higher but distribution is not affected.

But suppose of the 5 extra, 1 person gets three extra, one person gets 2 extra (=5), and the other two people get zero increase. The price will rise but because effective demand is unequally distributed, some people will have more purchasing power and others less. This is what happens in an inflationary environment, where asset prices increase first and wages last.

The top of the town makes out (3), the upper middle class does OK (2), and the lower middle class and poor working class are left holding the bag. Generally speaking, asset appreciation is not recognized as inflation so it is not addressed, and asset holders and those gaining from economic rent do very well. Inflation does not get addressed until wages begin rising as workers demand more income to keep up with rising prices. Then the monetary authority steps in and raises rates (price of money) in order to cool demand by raising the price of money. Inventory builds up as demand contracts, recession sets in, unemployment rises, and wages fizzle.

Thanks Tom your time and effort are very much appreciated.

Cheers Punchy

Fiscal austerity and continual increase in prices seem incompatible. Wont fiscal austerity reduce demand taking pressure off prices?

Also increasing energy costs will reduce demand just like a tax or interest rate increase. That reduced demand should result in reduced prices not an increase shouldn’t it? I get we may have capacity constraints forming but this ability to supply real goods to eat will be helped by reduced demand due to rising prices. Even the new middle class in China are not immune to the effects rising energy prices has on their ability to consume. Under these conditions we have an obligation to subsidise food purchases for any Country that needs food.

Rising energy prices, Global Warming (now Climate Change because GW was too hard to prove), fiscal austerity, currency imbalances, debt reduction, real estate bubble (Australia may still have one), retail under siege from Internet are all insignificant if there is any father and mother on the planet who cant feed their kids a balanced meal tonight.

The size of JG pool relates not to the decision of the government but indicates the effectiveness of government economic policies. It means that by tweaking other policies, e.g. taxation, the government can both increase or decreasing the “equilibrium” share of JG pool. As a residual macroeconomic policy JG should be used only to mitigate negative effects but JG only addresses consequences and not the reasons of changes of private sector spending decisions. A permanent rise in JG share reflects changing economic conditions which is equivalent to increasing sub-optimality of existing economic policies of the government.

A permanent rise in JG share reflects changing economic conditions which is equivalent to increasing sub-optimality of existing economic policies of the government.

This is important to consider. The US has had a dismal record of job creation over some years with the result that employment and underemployment are threatening to become structural. There seem to be no will for either a basic income or job guarantee, so the outcome is now uncertain and does not portend well.

However, neither a BI or JG is ideal under the circumstances in that it creates a permanent underclass with virtually no chance of escape, other than for a few lucky or very talented individuals.

Government policy needs to take this into account. For example, without redirecting rent to productive investment in the US, the problem will only grow in the face of global labor arbitrage until the global wage levels. Multinational corporate profit gained from outsourcing should be taxed away as rent in order to encourage domestic productive investment.

This post is geared to a JG. But what does MMT say for those countries which have yet to (and it could be some time before they) implement a JG?

What about the UK for example, with its 3-4% CPI from imported commodity price inflation – what (short of implementing a JG) should the govt do?

Thanks

Anders

The 3-4% CPI in the UK is 50% attributable to an increase in sales tax. The CPI ex that is only 1.6%.

Bill, I agree with your analysis and definitions. BUT regarding the 1970s, correct me if I’m wrong, but during wasn’t the inflation (a) already taking place *BEFORE* the oil shock (in fact, 2 months prior to the ‘shock’ monthly CPI in the US rose by 22%) and was maintained throughout the 1970s – even though oil prices fell throughout the remainder of the decade;

(b) with Australia being an exception, weren’t real wages actually FALLING during the 1970s? (hence, NO wage-price spiral);

(c) Didn’t profits during the 1970s for the top 50 US corporations in fact rise by 300%?;

(d) if wage explosions were the cause of the 1970s recession or unemployment more broadly, why did construction employment fall, and why did it remain very low during the 1975-78 period? Might it have something to do with the vacancy rates of 40% (due to excess supply from the 1972-73 property boom)? This suggests more of a Minsky FIH view on the cause of the 1973-75 recession. Point (c) may be consistent with your mark-up points.

This leads me to conclude that the 1970s inflation was just as much as a DEMAND SIDE, as a supply side issue (although bottlenecks did exist) – (1) Big Government – quite rightly (it prevented a depression!) was the cause of the 1970s ‘flation’ in stagflation – transfer payments rose exponentially (hence, why healthcare inflation was something like 20% or above) and (2) the unemployment was due to the ‘hangover’ of the previous property boom.

Bill, any comment on the above views?

Caveat: (b) with Australia being an exception, weren’t real wages actually FALLING during the 1970s [in places like US, Japan and the UK]? (hence, NO wage-price spiral);

Thanks Neil – so the question is then: if the UK’s ‘normalised’ / ‘recurring’ inflation were 3-4%, would this warrant some management downwards of agg demand by fiscal or monetary means? What if inflation were at this level but unemployment were still c. 8-9% – or is this a contradiction in terms?

Spadj,

(b) with Australia being an exception, weren’t real wages actually FALLING during the 1970s? (hence, NO wage-price spiral);

Well the wage-price inflation spiral is a nominal battle. The fact that real wages fell means that prices won.

But I agree with some of your other points. There is some evidence that the 1970s inflation was caused by monetary factors as well as supply-side factors. Inflation in Australia was rising before the OPEC oil price increases in 1973.

“What if inflation were at this level but unemployment were still c. 8-9% – or is this a contradiction in terms?”

If ‘ifs’ and ‘ands’ were pots and pans…

If you have inflation and unemployment then you have ‘stagflation’, which probably means there are real supply side restrictions that need dealing with (planning and land banking . Government then has to force somebody to absorb the real costs associated with freeing those up. In the 70s Maggie came to power and forced the labour part of the economy to absorb the cost.

Gamma,

Glad you agree with my other points, and while I agree that the wage-price spiral is a nominal battle, even in nominal terms there were not BURSTS of wages – I’ll try and dig some research up on this. Perhaps you know some?

In any event, I don’t think this explains stagflation of the 1970s – as I said, one should look at the property bubble bust of 1973-75 and its 2-3 year aftermath.

Neil – cheers. Any idea whether Bill has blogged on supply-side constraints / stagflation in detail?

This post was that!

Bill refers above to the conflict theory, but the only ‘solution’ to stagflation I can see is the traditional approach of increasing interest rates to increase unemployment and reduce workers’ bargaining power; unless he is saying that govt spending to reduce workers will increase AS so that it exceeds AD, reducing inflation?

Wait wait wait. Surely in an inflationary environment which is *not* stagflationary, the JG pool will drop to its minimum size as full employment is achieved wihtin the private sector. How then do you control inflation? I realize this is an extremely theoretical possibility. But suppose this happens, full employment in the private sector, wages continue to go up in the private sector, firms raise product prices to maintain margins, the prices are paid for by the workers with their increased incomes, we continue with the classic wage-price spiral, and we get a long, steady inflation, *except that the value of the JG program drops* because ths price offered for it is losing real value.

Oh — I get it. You said that the JG is *price targeted*. That means that if the economy overheats, you raise the wage paid to people in the JG program, thus sucking people out of the “productive” sector of the economy.

The political environment necessary to *raise* the wages of people in a make-work program in order to cool down the economy is tough to get.

I think to do it you have to express it differently. You have to have not a job guarantee program, but an income guarantee program, and call it a “worker conservation program”, much like the “soil conservation program”. Explicitly say that people are working too hard and what this country needs is more people devoting their time to bettering the world. Pay people to study (to become better citizens); to do the sort of jobs massively underprovided by the private sector, but not essential (the ones usually done as hobbies or as volunteer or charitable work); pay people for the sort of public works projects which are routinely underprovided but not absolutely necessary; hell, pay people to be writers and musicians. (The essential jobs must be filled at all times so they can’t be part of a JG program, but these are classes of jobs which clearly could be, and which traditionally are not well-paid anyway). But you have to have a political selling point for raising the wages of people in these JG jobs when there’s huge demand for working in the “private sector”, and I think the only logical selling point is that of the French: people are working too hard, more people need to be working on making our lives better.

No, wait, I still don’t see it. There’s still a problem here: the wage-price spiral can only be cut by removing *somebody’s* pricing power. Whose is it?

Increasing the number of people in the JG sector simply tightens the labor market in the corporate sector without reducing their desire to set prices and raise profit margins.

I suppose if you assume most businesses or most households are financial-capital-constrained in this environment that you can raise lending rates to businesses, which we’ll assume the central bank can do. But will all businesses will be financial-capital-constrained in this environment. They could be constrained only by a lack of physical capital, or by the hard resource limits on the time it takes to expand capacity, without being constrained by finance. They could all be Berkshire Hathaways, sitting on mountains of cash. In which case what?

There’s a fundamental problem that when sufficient wealth is legally controlled by private actors the effective money supply, the velocity of money, and inflation, all become immune to government control. So if you have sufficiently many private actors with sufficiently much wealth, how does the government regain control?

I suppose the answer is a suitable form of taxation, sufficient to restore people’s and business’s spending to a cash-and-borrowing-constrained state, by sucking the money out of the actors who have huge “savings” credits.

Or, in the alternative case where it is banks who have manufactured the money to meet demand, I guess we need banking regulations.

Private banks could obviously create really dramatic inflation bubbles if they could get everyone to accept their privately printed currency, and can evidently arrange to do so without paying significant taxes under any of the current tax systems.

The current disasters are partly caused by banks deliberately arranging to make loans in arbitrarily large amounts, and *not* going to the Fed to finance them; simply failing to finance them, basically, not getting deposits at all, not selling anything, just using shells and accounting fictions to create more liquidity. This is money creation pure and simple, it can be used to keep a wage-price spiral outside of government control if the bank so chooses (though it was used for other purposes this time) and yet I don’t see how the government can control it, except through intensive regulation of the operation of banks.

I can lay out explicitly where the money gets created in the current scheme: it’s when the bank “sells” the “securitized” mortgage to another bank, who credits it as a liquid asset and therefore claims to have the same amount of money to lend as before, thus evading the bank regulations. The bank which “sells” the mortgage also claims to have more money, because of the money the second bank gave it, and credits this money to the account of the borrower. Essentially, the transmutation from long-term to short-term is a manufacture of money.

Given the ability of the private sector to manufacture money to order, how on Earth is the government or the central bank supposed to cut a wage-price spiral? The only way is to *discredit the private money*, isn’t it?

OK, one further thought. Stagflation. If you’re running with the conflict theory, then the alternative to breaking *workers’* bargaining power is to break the price-setting power of *capital*. Price controls seem to be an excessively blunt instrument for this. An excess profits tax, such as was implemented during wartime in many countries, would probably do nicely.

You may have to break both sides’ price-setting power if the loss of real income is large enough. 😛 Which is why it’s important to have an environmentally sustainable economy which is resilient to external shocks.

Dear Nathanael (at 2011/04/02 at 2:24)

You said:

The JG wage is fixed and that is the point. It provides the nominal anchor. The government never tries to compete at market prices with the private sector.

I think you need to read more about the JG.

best wishes

bill

I think Nathanael is confused because this is a separate, non-automatic disinflationary mechanism from the JG buffer stock, where private sector inflation takes people out of the JG, which is an automatic fiscal tightening. What Bill is saying, as I understand it is that when we have serious, bubblicious inflation, the government can create a depression to deflate and simultaneously cure the depression by the JG: Net result, a few more on the government payroll at the fixed JG wage & less inflation. This is No-More-Mr-Nice-Guy, MMT is getting Austrian on you anti-inflation.

Of course neither mechanism is necessary, because laissez-faire capitalism is 100% stable, provides 100% employment, and our pets would all have flying cars that could reach Mars in 1 minute if we just left the free market alone. 🙂