I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Economy faltering – Australia’s wind-up Treasurer “We will cut harder”

On May 10, 2011, the Australian Treasurer delivered his Budget Speech 2011-12. At the time I wrote these blogs – Australian Federal Budget – more is not less and Time to end the deficits are bad/surpluses are good narrative. Some 6 months later the Australian government received news (November 07, 2011) – Swan warned on surplus timeline – that indicated the economy was slowing and tax revenue was going to be much lower than estimated. It is becoming obvious to most people now (what was clear months ago) that the Government’s obsession with achieving a budget surplus is undermining the growth prospects of the economy. They should never had withdrawn the fiscal support in the first place but now they should definitely abandon this surplus obsession. The Australian Treasurer was like a wind-up doll yesterday when told the economy was faltering. All he could say was “We will cut harder”. Moronic.

The report from a private forecasting firm suggested that the Government had to abandon its “plan for a budget surplus in the next financial year” and that “further cuts to spending as the Government tries to honour its pledge to get back into the black by the end of 2012-13 … could harm the economy”.

I would say will definitely harm the economy.

The report merely repeats what some of have been saying for months – when the Treasurer first made the pledge – that the economy is not strong enough (that is, external activity and private spending is not strong enough) to justify a surplus or allow a surplus to be achieved (without massive damage to real GDP growth.

The Treasurer said in response that:

We’ll take commonsense decisions … We’re always on the lookout for savings. We’ve been up for a very big savings task over four years. We will be making further savings with this process but we’ll do it in a way that’s consistent not only with the economic outlook but with our fiscal rules.

He later elaborated:

We are certainly determined to bring our budget back to surplus in 2012/13 … That means tough decisions will have to be made in terms of the budget … In past budgets we have found over $100 billion worth of savings. So we go through that process.

He also accused the Opposition of preaching a “bit more voodoo economics” when the latter changed a policy which left their own budget surplus estimates some $A70 billion short.

To understand why this obsessive pursuit of fiscal rules is damaging the following logic applies.

The budget estimates were based on assumptions that at the time were too optimistic and in the passing of time have been revealed to be so. The constant narrative that our “once-in-a-hundred-years” mining boom was going to bring bounty to all of us has fallen well short of realisation. Employment growth has been virtually zero for some months and other indicators of growth are faltering.

The ABS published the latest International Trade in Goods and Services, Australia for September 2011 today which showed the trade surplus (before invisibles) narrowing with exports falling on the back of declining terms of trade (so prices rather than volumes falling).

The The RBA Commodity Price Index is showing that commodity prices have fallen by around 4 per cent in the past three months.

The talk among those who analyse the data is that the export boom is slowing and increasing current account deficits (with trade deficits) are likely.

The private sector in Australia has not filled the spending gap left by the government fiscal withdrawal. There was no sound reason to assume it would given how much debt it is carrying as a result of the credit binge leading into the crisis.

The external sector continues to act as a brake on growth.

So tax revenue is falling below estimates because real GDP growth is not as robust as the Treasury claimed. Further, the world economy is imploding which will further undermine our export revenue.

The Treasurer at that point should admit this and demonstrate leadership by introducing new fiscal stimulus measures to ensure our growth trajectory lifts and we avoid getting dragged back into the mire that many advanced economies are now headed for (or in).

Let’s go back to May 2011 when the Treasurer delivered his Budget Speech. In that Speech he said (among other things) that:

1. “the purpose of this Labor Government, and this Labor Budget, is to put the opportunities that flow from a strong economy within reach of more Australians. To get more people into work, and to train them for more rewarding jobs. So that national prosperity reaches more lives, in more corners, of our patchwork economy”.

2. “And to succeed in the good times as we did in the bad – by choice, not by chance – by applying the best combination of hard work, responsible budgeting, and well-considered policies to the difficult challenges ahead”.

3. “And just as deficits are the right thing to fight a global recession, or to rebuild from natural disasters, so too are surpluses right for an economy set to grow strongly again. We have imposed the strictest spending limits … ensuring our country lives within its means. We are on track for surplus in 2012-13, on time, as promised”.

4. “our commitment to tightening our belt has not diminished one bit. We’ll be back in the black by 2012-13, on time, as promised. The alternative – meandering back to surplus – would compound the pressures in our economy and push up the cost of living for pensioners and working people”.

5. “We will reach surplus despite company taxes not recovering like our economy”.

6. “Our economy transitions from sluggish growth to stretching at the seams; our Budget from deficits in tough times to surpluses in better times”.

And so on … you get the message.

This is the same nonsense that has driven the UK economy backwards since the new government took office in May 2010. Claiming that consumers and firms were just waiting for a commitment by government to lower the budget deficit before they would unleash a renewed spending burst (the Ricardian equivalance argument), the British government embarked on a harsh austerity drive – with the worst is yet to come.

The British economy started to slow almost immediately they were elected and promising drastic cuts and has been going backwards ever since. Yesterday’s release of the BRC-KPMG Retail Sales Monitor – which has a good track record in predicting movements in spending showed how bleak things have become in Britain.

The Monitor reports that:

UK retail sales values were 0.6% lower on a like-for-like basis from October 2010, when sales had risen 0.8% … Food sales growth slowed and non-food sales also weakened, with big-ticket items suffering most.

The official commentary went like this – “Which part of the wave we’re riding varies from month to month but the water is consistently chilly … This is evidence of the basic weakness of consumer confidence and demand and worrying this close to Christmas”.

There has been almost “no growth in non-food sales”.

The British government is single-handedly undermining private sector confidence and destroying jobs and private wealth. History will not judget their obstinate pursuit of free market ideology very well.

So while the Australian economy is not in as bad a shape as Britain the same vandalism by elected governments is out in force.

In Budget Paper No 1 you find the Table 1: Domestic economy forecasts, which provide the forward estimates of the key economic indicators that condition the budget estimates.

Budget Paper No. 1 says:

The current account deficit is expected to narrow sharply in 2010-11, reflecting the expected increase in the terms of trade, and then widen in 2011-12 and 2012-13, reflecting strong growth in import volumes and the expected gradual fall in the terms of trade. The trade balance moved into surplus in 2010-11 and is expected to remain in surplus over the next two years. The net income deficit is expected to widen over 2011-12 and 2012-13, as rising export earnings generate increased equity income outflows.

I agree that is likely to occur – an ongoing deficit – or drain to domestic demand (spending). This is one of the areas of macroeconomics that people find it hard to get their head around. Australia is enjoying record terms of trade (the prices of exports relative to imports) and export volumes are strong.

And with all the crazy commentary in the media (which is tapering off lately) about our “once-in-a-hundred-year” mining boom creating conditions of wealth never before seen, it is little wonder that people are looking for the golden lining.

But the reality is that the external sector remains a contractionary force because more of the income we earn from our booming exports are going into imports. So the rest of the world is actually enjoying our mining boom in terms of growth impetus. We end up with lots of imported gadgets etc but a drain on growth. I realise this is hard to for people to understand.

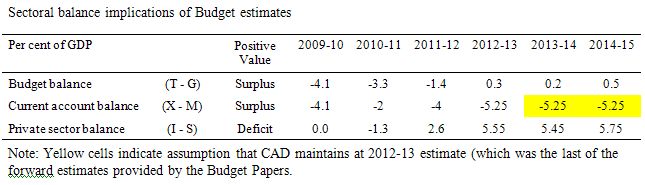

The following Table is constructed from the actual Budget estimates presented in May 2011. The Budget balance and Current account balance are taken directly from Budget Overview (budget balance) and Budget Paper No 1 (external balance).

The Private Domestic Balance is then computed according the National Accounting rule that the sum of the balances has to equal zero.

- The budget balances (T-G) – is positive if in surplus and negative if in deficit. T is total taxation and G is total government spending.

- The external balance (X-M) – is positive if in surplus.

- The private domestic balance (I-S) – is positive if in deficit (spending more than income) and vice versa. I is total investment and S is total private saving.

Please see this blog – Saturday Quiz – November 5, 2011 – answers and discussion (Question 2) – for a more detailed discussion of the way the sectoral balances are derived and interpreted.

The point is that the forward estimates are based on the range of assumptions that the Treasury make about government spending and tax policy settings, private spending growth, overall real GDP growth, inflation, interest rates, the labour market etc. Based on these assumptions, the national income trajectory would deliver these outcomes.

So this is what the Australian Government thought would happen back in May 2011 and reflected their fiscal strategy over the next several years. You will appreciate the following points:

1. The Australian household sector is carrying record levels of debt as a result of the credit binge prior to the crisis. It is now trying to increase its saving ratio back to the norms that pervaded before the financial sector unleashed the array of tantalising credit products.

2. The Australian property market is overvalued by a considerable margin as a result of the boom and prices are now dropping. I don’t expect there will be a collapse in the housing market along the lines we have witnessed in the US and in Europe but there will be an increasing number of Australians with negative equity over the next several years.

At the time I noted that the Government’s growth strategy hinged on the private sector going further into debt as the public sector withdrew spending support for the emerging growth process. Even at the time of the budget in May it was clear that private spending was weak and the intention was to save.

The other point is that the growth strategy replicated the circumstances that led the world into this crisis – a reliance on the private sector borrowing increasing amounts (spending more than it earns) – to drive spending and hence output growth.

At a time when the private domestic sector should have been deleveraging significantly (and for several years into the future) the Government was deliberately putting into place a strategy that relied on exactly the opposite occurring.

You will not read any analysis like this in the official Budget Papers. It certainly wasn’t in the Government’s political interests to admit that it could only achieve the planned surpluses by 2012-13 if it created conditions that forced the private sector into further indebtedness overall.

The reality is that the Government despite their “tough talk” were never going to succeed in achieving their fiscal ambitions. The reason – growth will not be strong enough. Why? Because the external sector is not adding to growth despite the boom and the private sector is now resuming more normal patterns of spending and saving. I say more normal to mean the behaviour that was evident for decades before the neo-liberal free market credit binge occurred.

In these “normal times” the Australian government ran budget deficits to support growth. The recent period of budget surpluses (1996-2007) was abnormal. On the rare occasions that the Australian government has run surpluses, a major slump has followed. That pattern is common in most nations – especially if they run external deficits.

Even the Canberra Times Editorial today (November 8, 2011) was calling for the Treasurer to abandon his surplus obsession.

They said:

Wayne Swan’s commitment to returning the federal budget to surplus by 2012-13, first made in the depths of the global financial crisis in 2009, has wavered little in the 2 years since. Nothing – not continuing economic uncertainty, declining tax revenues, draconian public sector ”savings” nor the misgivings of some economists about the necessity of a surplus in such circumstances – has been allowed to influence the Government’s thinking. However, a sharp deterioration in the Commonwealth’s financial position since the May budget makes it highly unlikely the goal of a $3.5 billion surplus by 2012-13 will be achieved.

They note that the Treasurer’s “determination that the deficit should be wiped by the appointed date is understandable from a political standpoint” given the Labor government has chosen to set the political terrain over fiscal responsibility in straitjacketed mainstream terms – the bigger the surplus the better – no matter what.

They are desperate to be seen by the electorate as “efficient economic managers” and so the surplus becomes an imperative.

It tells you how misguided the public debate over economic policy and budget outcomes has become. The electorate are so indoctrinated into believing that surpluses are good and deficits are bad that the actual reality is lost.

The Canberra Times adds to this nonsense by saying that:

Though a laudable aim of governments, budget surpluses are not always to be regarded as the fiscal equivalent of the holy grail.

Why are surpluses a laudable aim of governments?

Why is it laudable for government to deliberately:

1. Aim to increase the overall spending gap (fiscal drag) especially when the external sector is always in deficit (dragging on growth) and there is at least 12.5 per cent of willing workers idle according to the ABS (either unemployed or underemployed).

2. Force the private sector to have less purchasing power than otherwise.

3. Ensure there is less private employment.

4. Ensure there is less public employment.

5. Ensure there is less public infrastructure investment.

6. Ensure less education and training is provided.

7. Ensure there are less public services provided.

8. Ensure there is less scope for income support.

It is a different matter if a nation is running a strong external surplus (such as Norway) so that the first-class public services can be provided and full employment sustained at the same time as the private sector can save to their desired levels.

But that is a rare situation and one that Australia has never found itself in in recent decades. In our context, budget surpluses are very damaging to the economy.

The Canberra Times Editorial continues in this vein:

Indeed, in times of economic uncertainty they are undesirable (and probably unachievable). What is of greater importance is that governments run more surpluses than deficits over the economic cycle.

Again more confusion. Running “more surpluses than deficits over the economic cycle” is another ridiculous rule to aim for. Even so-called progressive economists fall prey to this seemingly reasonable ambition.

The logic goes like this. When the economy falters, it is okay to run a deficit. But overall the government should run surpluses.

Why is that reasonable? It just means that over the cycle the private sector would be running deficits that we equal (on average) to the average external deficit over the cycle. In other words, the private sector would be – on average – be continually spending more than they earned. The crisis was caused by that sort of growth strategy.

Any pre-imposed fiscal rule about budget balances make no sense at all. The only approach that makes any sense is to start by defining why we bother with government in the first place. We want government to advance the well-being of the populace. We might call this the public purpose role of government.

The state should maximise the potential of its population. The sustainable goal should be the zero waste of people! I consider this at least requires the state to maximise employment. Once the private sector has made its spending based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

Non-government spending gaps over the course of the cycle can only be filled by the government. The national government always has a choice:

- (a) Maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap – that is run budget deficits commensurate with non-government surpluses; OR

- (b) Maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a budget surplus will be possible.

The irony and this relates to the Canberra Times bracketed assessment that the budget surplus is “probably unachievable” anyway, given what is happening in the economy, is that taking Option (b) in the hope that the fiscal austerity will deliver the surplus will probably result in a deficit anyway.

I call those sort of deficits – bad – because the economy doesn’t get anything good to show for it. The deficit is driven by rising unemployment which means tax revenue declines and welfare payments rise – a state of general malaise.

The automatic stabilisers ultimately close spending gaps because falling national income ensures that that the leakages equal the injections – so sectoral balances hold. But the resulting deficits will be driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

Alternatively, taking Option (a) produces good deficits because the public support for aggregate demand keeps output and employment growth strong and consistent with the aspirations of the workforce (for work) and incomes high.

Option (a) also generates virtuous movements in the automatic stabilisers (rising tax revenue and declining welfare spending because activity is high) which has the effect of reducing the deficit anyway.

Fiscal sustainability is about running good deficits to achieve full employment if the circumstances require that. You cannot define fiscal sustainability independently of the real economy and what the other sectors are doing.

Once we focus on financial ratios, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

That is why fiscal rules as stand-alone goals are meaningless or ideological. Please read my blogs – Fiscal rules going mad … and Fiscal sustainability and ratio fever – for more discussion on this point.

This suite of blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – also bears on this topic.

The Canberra Times Editorial does make some sense though and seems to realise that now is definitely not the time to be trying to run federal surpluses:

The GFC was a clear-cut case of an economic crisis that warranted a large dose of Keynesian pump-priming. As a result of the size and speed of Labor’s stimulus measures, Australia was one of only a handful of developed economies to avoid a recession. Nevertheless, and despite this achievement, Labor apparently remains obsessed by the notion that the one true indicator of good economic stewardship is a budget surplus, and that this can and must be achieved, even if it requires further cutbacks government outlays. However, a further round of austerity cuts at this time – when the global outlook remains uncertain and signs of weakness have reappeared in the Australian economy – is questionable, and probably unwise. As hard as it as to walk away from this particular promise, Mr Swan should accept that circumstances have changed and adjust his goals accordingly.

They should have gone further. A “further round of austerity cuts at this time” would not “probably” be “unwise” they would be completely irresponsible and demonstrate just how little the Government knew about sound fiscal management.

I don’t deny the politics are pushing the Government in this way.

The Opposition has been claiming that they would cut spending further to achieve a surplus – clearly thinking that the dollars the Government spends go no-where!

In reply to yesterday’s report, the Opposition Treasury spokesperson said:

This just confirms what we’ve been saying for an extended period of time … Labor can’t deliver surpluses, it’s not in their DNA. They haven’t delivered one since 1989-90, and I suspect they’re not ever going to deliver a surplus.

The facts are that since 1989-90, the Australian Labor Party’s tenure (to 1996 and then from late 2007) in government has coincided with two massive recessions – early 1990s – the worst downturn for Australia since the Great Depression and now the current crisis.

There is no way the government could have delivered a budget surplus in those year even if it had wanted to (which they did!).

Last night, as it became clear that the economy was shrinking and tax revenue was going to fall well short of the estimates, the Opposition leader said:

I think it’s important that the Government gets us back to surplus. I doubt very much that this government has the ticker to do so … Obviously if the Government does deliver the fiscal responsibility that Australia needs, we’ll applaud it … There are so many examples of waste under this government, the classic example is the $50 billion-plus national broadband network …

Meaning he would cut the only innovative infrastructure (fibre national network) project that this Government has introduced which will deliver massive benefits to future generations once in operation. It is akin to the development of railways and highway systems in the C19 and C20 century.

I do not support wasteful public spending – but I realise that it is a vexed area trying to determine what is wasteful or not. But what is important to realise is that whether the spending is wasteful or efficient doesn’t figure when we consider the impact on aggregate demand.

A dollar wasted has the same impact on overall activity as a dollar well spent.

So while I applaud attempts to cut waste – and I would start by cutting consultancy budgets and the sort of salaries that management get in public institutions like government departments, universities and statutory authorities – cutting spending to eliminate waste introduces the imperative to replace it with “good” spending to ensure that aggregate demand doesn’t falter.

When the conservatives rail about cutting public waste they don’t understand this point at all.

Conclusion

But the point is that by compromising sound economic management by political considerations just means the Government is failing on both grounds. They are failing to provide political leadership which would necessitate they disabuse the public of these notions that surpluses are good and deficits bad.

And by bowing to the rabid conservative hatred of deficits they are undermining the health of the economy.

What the whole debate misses is that Any financial target for budget deficits or the public debt to GDP ratio can never be a sensible. The budget outcome is largely endogenous!

It is highly unlikely that a government could actually hit some previously determined target if it wasn’t consistent with the public purpose aims to create full capacity utilisation.

Further, the government cannot impose incompatible goals on the economy. So with external deficits, it is impossible for the private domestic sector and the public secotr to run surpluses.

There is a need for a new macroeconomics narrative as a demonstration of political leadership. A revised macroeconomic narrative can help us understand: (a) The operational features of the monetary system; (b) The opportunities each monetary system presents to the national government.

A sovereign government always has the capacity to maintain continuous full employment. To achieve that goal – and bring the political and economic dialogues into accord – we have to abandon the focus on financial matters and reorient the debate toward the real side of the economy.

A new macroeconomic narrative is essential if the public is to be disabused of the myths that have been used to erode the collective will. Governments that abandon full employment and then punish the victims of this policy failure including low wage workers should not be supported. A fiscally responsible government aims to maximise the potential of all of its citizens. Public policy should always reflect that goal.

In response to the news that the surplus goal was unlikely to be possible, the Australian Treasurer just said he would cut spending further. The same nonsense that is killing Europe, the UK, and other places that have imposed fiscal austerity as a matter of ideology rather than good management.

The other point is that if they actually understood what was going on they would have realised the the surplus obsession was bad politics anyway. They were never going to achieve that goal given the other parameters and so they have just set themselves up to fail – yet the electorate will not equate failure in this case with a good outcome (which it is). That is how tragic the whole situation is.

That is enough for today!

It all boils down to fixed amount of money thinking. They genuinely believe that if government doesn’t spend the money somebody else will – not realising that banks simply aren’t the 100% efficient recyclers of money they believe they are.

It’s homeopathy vs modern medicine again.

Sad thing is, the other lot aren’t going to be any better. I’m not confident that any of these clowns even has a tenuous grip on reality at best.

Many right wing movers and shakers fully understand the significance of deficits/surplus vis a vis fiscal policy and monetary policy. They do get MMT. It’s impossible to believe senior bankers working closely with treasury and central banks don’t understand the system they designed and operate themselves.

Why do they keep chanting like sheep….surplus good….deficit bad?

A) They are in opposition and say it to discredit the ruling party. It is an argument easily accepted by general public. Same thing when Thatcher came to power there was a ‘high pound good…low pound bad’ mantra to dicredit labour policy of the day. Now in a different economic environment the Conservatives are applauding themselves for devaluing the pound.

B) The elites don’t work for a living in the same way as us mere mortals. They organise others work, living on economic rent and surpluses of others labour. They will favour any policy that keep wages low and profits high.

C) The primary objective of modern political parties is to get power by saying whatever they think people want to hear (or can be led to believe). The deficit lie is as good as any other lie in that regard.

Most people I talk to seem to believe that a countries’ finances are just like those of a household. Try to tell them and explain the differences and they will not even listen. I’ve tried many times now, the reaction is instantaneous and usually follows the same pattern. Finding a way through takes more time than the timespan of attention that people now seem to have. They want answers, they want change; but they won’t work at it. Depressing…

Access economics sums up the situation perfectly….

“”Mr and Mrs Suburbs think a dollar in surplus means you’re a genius, and a dollar in deficit means you’re a dunce. Politicians of both sides have played to that. They should back off.”

“Abandoning the surplus will be a bitter pill for the government to swallow and an easy target for the opposition to attack. The government should do it and the opposition should hold fire.”

http://www.petermartin.com.au/2011/11/there-aint-going-to-be-budget-surplus.html

Sad to say, but at this point in time, abandoning the stated goal for a federal budget surplus pretty much hands the next election to the opposition on a silver platter.

Politicians have such a poor record in spending the public purse or explaining the value of doing it that they would sooner espouse public spending cuts as they know the public will lap them up thinking it is doing the country good.

It is all about power and will always be so until we have some political leaders with backbone who see the big picture. If one of the main developed countries did take MMT seriously and made good decisions the rest would follow like sheep because thats what they do!! Very sad really.

I actually had a great laugh out loud moment yesterday evening driving home from Work.

On RTE radio in Ireland they interviewed Rachel Sanderson from the FT about the situation in Italy. The presenter asked her a fairly obvious question “Italy has had serious debt levels and deficit since the early 90’s. What’s the big difference now?

The Financial Times Journalist answers with complete authority saying something like “It’s a lot to do with confidence….. Italian Bankers very good but…….. now investors have looked at debt in a completely different way…. suddenly Italian growth is not strong enough so they have no ability to fund itself”

Complete nonsense. All she needed to say was, they no longer issue and control Lira but are slaves to the Euro madhouse! I’m not surprised people are confused.

You can listen to the exchange here at 1hr 19mins 50 seconds (will only last til about midnight 08-11-11)

http://www.rte.ie/radio/radioplayer/rteradioweb.html#!rii=9%3A3103151%3A83%3A07-11-2011%3A

@Richard

I have had similar experiences. They seem to get it during one conversation but at the next, they come up with the Tory bullshit. I think this is partly due to the deficit message being hammered down the air waves day after day while the opposite view hardly gets an airing. I don’t know how we can change this.

The mainstream journos also fail to put the other side on their own by offering it as an alternative in their reports. Even Paul Mason isn’t very good at this. He has been criticized for this but doesn’t seem to be taking it on board. And he is one of the decent ones.

I am a layperson in economics. However, it seems obvious to me that if;

(a) there is unutilised labour (both physical and intellectual capacity);

(b) there are unutilised resources (idle plant, wind power, solar power etc.);

(c) there are infrastucture shortfalls; and

(d) this could all be addressed by injecting money into the system by deficit spending;

then a government clearly ought to do (d) above.

Propositions a, b and c are uncontentious. All sides of politics agree that more employment, more utilisation of idle assets and resources in a sustainable fashion and better infrastructure are clear economic pluses.

The only apparent contention can be about the efficacy of deficit spending when the economy is soft or in recession. However, all the historical empircal evidence is that appropriate deficit spending does re-prime the economic system. We don’t have to look far back to see the truth of this. Australia’s deficit spending during the GFC was prompt, sizeable and reasonably well targeted. The only possible criticism was that it was withdrawn too soon. Australia survived the GFC in better shape than the great majority of countries.

We have to ask why (when a, b and c above are uncontentious and d is supported by at least 100 years of empirical economic evidence) is the prejudice and bias against deficit spending so great? Why is so much propaganda manufactured to “support” the notion that government deficits are always and everywhere a bad thing? Clearly, this false view must be in the interests of a powerful, manipulative class. I think an earlier poster on this blog (probably in a previous thread) hit the nail on the head.

He said essentially that the financialisation of the economy and the defacto handing over of the management of money supply to the private banks (along with the spurious notion that fiat currency issuing governments need to borrow money from private banks) is the main point of the game. It is finanacial and corporate capital taking over the running of our society and in the process rendering democratic government impotent.

This is an extremely dangerous trend and is in fact the final stage of what some call the dictatorship of capital. Where democratic wishes are suppressed and this is combined with ever greater financial slavery and even real impoverishment of the masses, this will lead to violent upheavals in our society. The violent upheavals in the middle east are greatly do with this same dictatorship of capitalism (albeit crony rather than corporate capitalism).

Bill,

Does this not mean the Central Bank is forced to stimulate by way of much lower cash rates? Surely then a halving of the household interest bill would be enough to re-stimulate credit and the economy.

I admit, there may be only one or two more cycles until we reach ZIRP, but the near term outlook is not as dire as you suggest.

Chris,

I’m not Bill, but if you follow the news you will see the RBA and bank chiefs “concerns” The household sector is entering a period of sustained de-leveraging. In other countries such as US and UK the deleveraging trend was not halted by falling interest rates.

Personally I think lower interest rates will allow Australians to keep servicing their mortgages. Taking some of the sting out of minuscule pay awards, rising costs and shorter work hours. No great property crash….. but not off to the races any time soon either.

Thanks Andrew.

I think your points are valid.

I think Credit growth is low because mortgage rates are 7% (which would have been the equivalent of 14% in 2005 when household debt was half). How much will this change if mortgage rates hit 2% (under ZIRP)?

And, to what extent is “de-leveraging” the choice of a household, versus the accounting realities of Government deficits?

Finally, why must we assume Australia will continue to run a current account deficit. Why does Bill assume this is the “constant”, and Government budgets must accommodate? If Australia swings into a CA surplus (say by way of a substantially lower AUD), then Swan get his balanced budget, and Australians can continue to de-leverage.

I am new to MMT so some of my comments may be naive. What am I missing?

Bill you said:

“What the whole debate misses is that Any financial target for budget deficits or the public debt to GDP ratio can never be a sensible. The budget outcome is largely endogenous!”

As if to prove your point, this article from the BBC:

“Canada delays balancing its budget”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-15648526

“Canada’s finance minister says he will not be able to balance the country’s budget by 2014-15 as promised.

Jim Flaherty blamed the European debt crisis for damaging Canada’s outlook.”

Kind Regards

Chris,

“If Australia swings into a CA surplus (say by way of a substantially lower AUD), then Swan get his balanced budget, and Australians can continue to de-leverage.”

Not sure what Bill would say, but I think that not issuing debt $-for-$ to match the deficit will alter the exchange rate as you describe – yet when you export basic commodities, there is often not much profit in that, compared to, say, hi-tech exports. Much of the plant and machinery needed in Australian mining may well be imported. I suspect it is not straight forward.

Bill –

The Canberra Times is right on this. Didn’t I explain this a few months ago?

1: Growth is determined by a combination of fiscal and monetary policy.

2. The slowing effect of a surplus can normally be compensated for by cutting interest rates.

3. Lower interest rates make it cheaper for businesses to invest, increasing their profitability. It also makes it easier for businesses to stay profitable, as it reduces their costs.

4. In a downturn, when interest rates are low anyway, surpluses should be avoided. But when the economy is going well, surpluses are a better way of controlling inflation than interest rate rises.

What objection do you have to this argument? It seems rather puzzling, as IIRC you were the first person I’ve heard suggest using taxation policy to control inflation.

The Reserve Bank has been too hawkish on interest rates, but that doesn’t invalidate the point.

Lower interest rates increase the purchasing power of the private sector and ensure there is more private employment, which counteracts the decline in public employment.

Running a surplus does not itself ensure any of those things. They’re all the result of a political decision to prioritize low taxation.

Why are you so obsessed with the myth of the private sector’s desired saving levels?

The budget surpluses were far less damaging to the economy than the tax cuts that ended them. The Rudd tax cuts didn’t result in full employment, but did result in higher inflation.

NO IT WAS NOT!

The crisis did not start in Australia, which almost escaped it.

The crisis started in the USA, which was running a prioritize low taxes growth strategy and running deficits.

As a preimposed fiscal rule, it doesn’t make sense. But choosing to give low interest rates greater priority than low taxes makes a lot of sense, and following that principle is likely to result in surpluses a lot of the time.

The only theoretical reason the private sector can not fill them is one of semantics – if the private sector fills them then they’re not non-government spending gaps. You could just as easily say that government spending gaps over the course of the cycle can only be only be filled by private enterprise.

But if you look at the total spending gap without preclassification, the government does indeed have a choice: it can fill them itself, or it can cut interest rates to enable the private sector to do so. The second option is very unlikely to be effective in a depression, but will be effective under normal conditions.

Aiden,

Good post. Much of what I was thinking (so my judgement is biased).

If / When we reach ZIRP the only way to kick start an economy is either

– Export led growth or

– Deficit spending

Until we reach this point, interest rate policy is highly effective. Remember rate cuts began a few months ago with the major banks cutting fixed loans by as much as 50bpts. Since then of course we have sen OCR reduced by 25bpts. Some interesting data points today;

1. Home loans continue to rise

http://www.smh.com.au/business/home-loans-continue-to-rise-20111109-1n6dp.html

2. Consumer sentiment has increased

http://www.smartcompany.com.au/economy/20111109-consumer-sentiment-reaches-six-month-high-after-rate-cut-midday-roundup.html

3. Myer has announced Retail sales gaining momentum leading into Xmas

http://www.smh.com.au/business/myer-welcomes-early-christmas-cheer-from-shoppers-20111109-1n65q.html

Aiden, Chris,

I strongly disagree. A side effect of increasing investment caused by lowering interest rates if bank lending is not curbed would be an acceleration in the growth of the stock of private debt as the current savers won’t dis-save and buy the equities (thus re-injecting money) just because the interest rates are lower.

The issue of the growth of private debt is something entirely overlooked by the mainstream economics and the root cause of the GFC. The last thing we need here in Australia is kicking the can down the road and more private debt! Bill is 100% right that the process of repaying that debt and shrinking the balance sheets of the banking sector needs to be accommodated by running the appropriate budget deficits. Then the existing savers would hold public debt instead of private debt, which would be partially repaid.

ZIRP of course makes sense to me but coupled with severe restrictions on lending for anything what is not strictly productive activity.

BTW I would interpret the news you mentioned in a slightly different way.

Ak,

Your comments assume private debt is too big.

I accept is is large (in fact larger than most countries), but how large is too large?

Surely the answer to that question is the cash rate – until recently 4.75%, and in no way are we experiencing the same economic conditions as the US / UK. We have had deficit spending but so too has the US.

I think there are a number of reasons why Australia can have a substantially higher level of private debt compared to other countries. But to name two;

1. Most of our private debt growth has resulted in growth in private superannuation accounts (MMT teaches us the private sector can not net save without Government / external accounts). People like Steve Keen have assumed credit growth has led to house price growth – I think our superannuation system and MMT contradicts this notion. Aussie super accounts are now +$1T, similar to household debt. So interest payments are being made to ourselves.

2. Australia has much better distribution of income versus most other countries. I know it could be better, but we are streets ahead of the US. This is important, because if the middle class have 10% increase in real income, then this can support +30% increase in private debt. This is because even without debt, households have operational leverage. So a 10% increase in real income can lead to a substantially higher level of DISPOSABLE income.

It is for these reasons (along with deficit spending) we have had 7.5% mortgage rates, and the economy has not tanked. It is for these reasons I see continuing credit growth.

Chris,

What percent of super is in cash and bonds?

Who has more the super…. Top 20% or bottom 80%

How many households have sufficient disposable income to service additional interest payments?

I should add, they can more easily support the interest payments when rates drop but they won’t take on much more debt because they dont want to be repaying capital when they are old and grey. More and more people believe the crazy crazy house price boom is well and truly over.

Interestingly, nobody will expect rates to stay low for ever, they fear being caught out if rates rise. Don’t tell them rates will still be near zero in 2030.

Hi Andrew

“What percent of super is in cash and bonds?”

About 20% excluding foreign cash holdings. But the amount of cash that has gone into the system since 1991 (actual cash payments) totals about $650bn. The $1.2T value includes $550bn mark to market which is not relevant in MMT. So $650bn increase in household debt can be attributed to the Superannuation System.

“Who has more the super…. Top 20% or bottom 80%”

Probably the top 20% – only because they have worked for longer and therefore have converted more of their intangible un-earned income into an asset.

“How many households have sufficient disposable income to service additional interest payments?”

Not sure what you mean by “additional” interest payments since I think we can all accept rates are now lower than last week, and likely to head even lower if Swan keeps pushing for his surplus.

But overall I reckon 99% of households have sufficient income to service their mortgage. Mortgage arrears in this Country are about 1%. I suspect this arrears number is now lower after the rate cut.

Andrew,

I’m not sure how you know what other people are thinking. Perhaps you are right, and no-one wants to take on more debt.

On the other hand, we have seen examples in other countries (with floating mortgage rates) continue to increase private debt (some well in excess of Australia) – and continued house price growth too.

Norway, Sweeden, Switzerland, and Canada come to mind. Interestingly, like Australia, they have a relatively broad distribution of income too.

Chris,

The process leading to an increase of the private debt and at the same time hoarding monetary assets while houses and other real assets appreciate is a one-way street with a thick wall at the end. Some countries like Japan, the US, Ireland, the UK have already hit the wall (the process of cleaning up the mess is well advanced in Japan where the crash happened 20 years ago). Central European countries are also affected by debt deleveraging. Canada, Australia and Israel are different but one may ask for how long.

We will see how negatively geared investors here in Australia behave when they realise that house prices stopped doubling every 7 years and how first home buyers react to negative equity. I don’t want to say that the bubble cannot be restarted by lowering the interest rates but my point is that the system cannot be restrained or stabilised – it either collapses under its own weight or expands in a bubble – because the driving force are either capital losses or capital gains and they drive the positive feedback loop from one extreme to another.

There is absolutely no reason to assume that the system based on private financing of investment and private superannuation saving leads to better allocation of resources than the state capitalism. Of course this is a kind of zero-sum game (or slightly-negative-sum game).

There are quite wide social groups in Australia like the infamous baby boomers who benefited enormously from the new order introduced by Paul Keating and John Howard. People who arrived too late have to pay for their lavish lifestyle a hefty mortgage tax. What is even worse, a lot of young people, not necessarily from the filthy migrant background (like me) but true-blue Anglo-Saxon Aussies are denied even the chance of being exploited.

We will see in a few years time what the long term effects of the neoliberal social engineering are.

ak,

not sure what you mean by “We will see how negatively geared investors here in Australia behave when they realise that house prices stopped doubling every 7 years and how first home buyers react to negative equity”

I’m not sure where you live, but in NSW between 2003-2008 there was flat prices (decline in real terms). So for about 1/3rd of Australians population the notion that “property doubles every 7 years” is not relevant.

So after 5 years of stagnant/ negative growth what did we get in 2009? +20%.

So the facts do not support the theory (like most neo-classical analysis).

Bottom line – MMT tells us most private debt / money creation has gone into superannuation – not houses. I’m not saying that’s a good thing. In fact it is a terrible thing, and will ultimately destroy the value of equities with too much capital chasing too little output. Like the Future Fund, Compulsory superannuation is a flawed policy.

Chris,

“Like the Future Fund, Compulsory superannuation is a flawed policy.” – I absolutely agree with that.

Some investors panicked in 2005/2006 – I had to move houses every couple of months because of that.

I am not entirely sure what you mean by “MMT tells us most private debt / money creation has gone into superannuation – not houses.”

You probably mean that the stock of the deposit money created when mortgage loans were extended finally ended up on the bank accounts of the superannuation funds and on the accounts of the foreign entities. That’s fine and I agree. What seems to be missing is what happened with that money between the time it was created and saved. A lot of this money was spent on buying housing assets – often the same housing assets over and over again thus leading to the ratcheting up prices process.

We must look at the flows of money when we analyse the demand for new and existing assets. I do not fully agree with Steve Keen that all the flow dL/dt stimulates the aggregate demand. Only that part of the volume of the new loans which is spent on purchasing new assets or spills over from the housing market (RE fees) has any direct impact on the rest of the economy.

Let’s look at the boundary case.

Imagine that we had 1000 houses worth $200k each and all of them had 50% of the owner equity. The stock of loans and debt was $100mln. What will happen if the prices for these houses are bid up to $400k and no mortgage repayment takes place? We have 1000 houses worth $400k with 25% of the owner equity and the stock of loans and debt increases to $300mln.

Much more can be said about the price ratcheting process but it is mostly related to the prices of land which is in (artificially) limited supply.

ak,

thanks for your response – I hear what you are saying re: MMT and flows into super. I will give this more thought.

Re: your example – if prices move above intrinsic value, it encourages new supply. Simple.

I know there are lost of conspiracy theories about land held back or artificial blocks in supply. I do not subscribe to this view for two reasons

– Property developers make money by maximising return on capital. Return on capital = margin x turnover. So developers are incentived to turnover (sell) land as often as possible for any given margin. There is very little incentive to hold back stock.

– A cursory glance at the annual report of any listed developer will tell you there are hundreds of thousands of blocks for sale. Stockland (4% of market) has over 30,000 for sale. The problem is price (not high enough). That is why supply is low.

Chris –

You’re overstating it a bit – remember a lot of countries are in a much worse situation than Australia, and we don’t need to reach ZIRP for interest rate cuts to be ineffective – all it requires is a situation where banks consider the risk of lending money to be too high.

Aidan,

Fair point