I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When you’ve got friends like this … Part 6

Today I continue my theme “When you’ve got friends like this” which focuses on how limiting the so-called progressive policy input has become in the modern debate about deficits and public debt. Today is a continuation of that theme. The earlier blogs – When you’ve got friends like this – Part 0 – Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4 and Part 5 – serve as background. The theme indicates that what goes for progressive argument these days is really a softer edged neo-liberalism. The main thing I find problematic about these “progressive agendas” is that they are based on faulty understandings of the way the monetary system operates and the opportunities that a sovereign government has to advance well-being. Progressives today seem to be falling for the myth that the financial markets are now the de facto governments of our nations and what they want they should get. It becomes a self-reinforcing perspective and will only deepen the malaise facing the world.

First up today was the Op Ed (August 31, 2011) – No excuse for inaction – by Adam Posen who is an external member of the Bank of England’s nine-member Monetary Policy Committee. He certainly wants more policy action given the danger at the moment faced by nations dipping back into recession.

He acknowledges that “most economists … [have] … acknowledged the grim outlook for the advanced economies” at present.

His diagnosis?:

Too much attention has been paid, however, to the failings of fiscal policies and to the shortfall from effects of earlier quantitative easing. Further asset purchases by the G7 central banks are needed to check not just a downturn, but the lasting erosion of productive capacity and of debt sustainability – especially when even justified fiscal and financial consolidation is undercutting short-term recovery. Easier monetary policy will increase the odds of other policies improving, and those policies’ effectiveness when they do.

To which I said to myself something unprintable.

He correctly says that there “is no credible threat of sustained higher inflation in the advanced economies that should restrain central bank action” and that

“(c)redit and broad money aggregates are barely growing and current account deficits are slowly shrinking” and that “interest rates on long-term G7 government bonds display no consistent rise in inflation expectations”.

So why does he say that fiscal consolidation (aka austerity aka scorching the domestic economic earth) is “justified”? If all these conditions are benign then a fiscal expansion is a much more direct way of stimulating aggregate demand than QE.

As I explain in this blog – Quantitative easing 101 – QE can only really stimulate demand by lowering longer-term (investment) interest rates.

It was erroneously thought that QE made it easier for banks to lend by adding reserves. Clearly that view is false. Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Further, hoping that a low interest rate environment would stimulate investment ignored the fact that business confidence is extremely low. Banks are not reserve-constrained in their lending. The major constraint is a lack of credit-worthy customers lining up for loans. The dearth of borrowers relates to the extraordinary uncertainty at present driven by a very sluggish growth environment which is being exacerbated by the foolish implementation of fiscal austerity.

In this regard, Posen offers this puzzling assessment of the QE actions to date:

True, the quantitative easing measures undertaken by the world’s central banks since late 2008 have not created a strong, sustained recovery. I warned in October 2009 that mechanistic monetarism could not be relied upon, that the stimulus from the stock of assets kept on central banks’ balance sheets would diminish faster than many expected, and thus that the only way central banks would know that they had made sufficient asset purchases was when the sustained recovery of domestic demand was achieved. That is an argument for G7 central banks to purchase more assets, while removing any fears of overshooting with such purchases. It is not a reason to give up on the effort.

So why hasn’t the substantial asset purchases to date been sufficient?

He claims that the QE in Britain and the US have had a “positive significant effect on consumption, on the relative prices of riskier assets, on credit availability, and on liquidity in the financial system” but that the dose wasn’t large enough.

Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for a detailed discussion which would challenge that point.

However, I agree with his statement that “(t)here are no negative side-effects to speak of from greater asset purchases, beyond some politically induced nausea” and that “all the claims of gold bugs and defenders of undervalued exchange rate pegs that QE was debasing the currencies of activist central banks have been proven unfounded”.

Finally, Posen uses a soccer/hockey/whatever analogy:

When you are the goalkeeper, there is no excuse for inaction, even if it is embarrassing when some shots do get past you, and even if your teammates fail to play defence. Additional monetary stimulus is the last line of defence for the advanced economies today. G7 central banks should purchase more assets if we are to have any hope of our economies ever catching up.

I agree that now is not the time for inaction and that the dive in world growth is directly related to the political malaise that has beset the advanced economies. It is clear that the conservatives do not have a growth agenda and are using their power (media, corporate etc) to white ant the nascent, fiscal-driven recovery for their own purposes.

But I don’t consider monetary policy in the form of QE to be “the last line of defence”. The evidence does not support an argument that QE is a very effective tool for expanding aggregate demand.

The main problem at present is the lack of overall demand. Fiscal policy tools are perfectly suited to stimulating demand – directly and quickly. The problem hasn’t been that the QE dose has been too conservative. The problem is that the fiscal expansions were too small in the first place and have been withdrawn too quickly.

Then I noted an article (August , 2011) – 4 Liberal Myths that Distort the Deficit Debate – in the Fiscal Times which has been described as “tycoon-funded propaganda”, the tycoon in this case being the deficit-terrorist supremo (the bank roller) Peter G. Peterson.

The Fiscal Times claims it is:

… an editorially independent enterprise, written, edited and produced by experienced professional journalists, that provides an array of original reporting and analysis.

If you examine the content you won’t find any articles about the “Million Conservative Myths that Distort the Deficit Debate.

See this interesting article (January 6, 2010) – Conservative Mogul Buying Up Reporters to Promote His Regressive Agenda – by William Greider which documents the origins of the “Fiscal Times”.

I also note our friend Mark Thoma who often claims MMT is simply wrong but refuses to debate that claim while also continuing to claim there is a money multiplier and banks lend reserves is listed as among the “Columnists, Analysts, Bloggers” who contribute to this rag.

Anyway, article noted above claims – after claiming that “How to Lie with Statistics is not just a book title” that:

The U.S. will never solve its debt and deficit problems unless we face reality … Here’s a reasoned take on a few of the most frequently garbled arguments making headlines these days.

Note: a balanced argument would not assume that the US has “debt and deficit problems” at the outset. What problems? The mainstream media just assert that now as if it is a truth.

Anyway, the fourth left-wing myths are:

1. “The Left proclaims that President Obama “inherited” the deficit crisis, and that it stemmed from the Bush tax cuts, two wars and the passage of the Medicare drug program”.

I note that some Democrats say this and are just as wrong as the Republicans who claim that “Longer term, entitlement outlays threaten our outlook” (which is one of the responses the Fiscal Times makes to the “myth”.

There is no deficit crisis. There is an unemployment crisis. Mass unemployment indicates deficits are too small not too large. Causality goes from mass unemployment to deficit not the other way around.

2. “Another favorite liberal narrative is that corporations don’t pay taxes”.

I agree that the left is crippled by these sorts of responses to the budget debate. They take it as written that there is a debt problem but then argue about who should pay to fix it up. One might want corporations to contribute more to tax revenue on equity grounds but any argument that says that we need higher taxes so that we can fix the deficit up without as many cuts to spending is missing the point completely. Unfortunately, the “left” falls into this hole often. See the discussion under the next “myth”.

3. “… the wealthy should pay a little more.”

I also agree that the left is crippled by these sorts of responses to the budget debate. They take it as written that there is a debt problem but then argue about who should pay to fix it up.

Such arguments play in to the hands of the conservatives. They are not germane to the current problems facing the US. At present, the only reason you would want the high income earners to pay more would be on equity grounds. There is no inflation threat and an urgent need for higher aggregate demand. Raising any taxes is contra-indicated.

So if you wanted to raise the taxes on the rich now you would certainly be looking for expansionary measures to ensure that the budget deficit increased. There is always the capacity within fiscal policy to increase spending while changing its composition (across sectors and income cohorts). That is the beauty of fiscal policy as a counter-stabilisation tool.

4. “Many on the left have argued that we should not cut government spending, suggesting that every dollar goes to programs essential to the survival of the United States.”

The response of the Fiscal Times is to argue that at least ” $100 billion of projects and programs” in the current US Budget “can be eliminated” because they are wasteful duplications.

This raises an interesting point.

I do not support public waste – which I measure in the way real resources are utilised by the public sector and the benefits of that usage distributed. Given our environmental imperatives (climate change etc) all of us should be seeking to economise on real demands on the environment and seek less environmentally-damaging ways to employ people productively and add values to our lives.

But presumably the “wasteful” spending is still entering the aggregate demand stream and helping drive growth in output and employment. In that sense, if you eliminate “waste” and “duplication” that is actually part of aggregate spending you have to replace it with less wasteful spending overall.

Cutting “wasteful” demand will not help the economy overall. The problem at present is a lack of aggregate demand. The distribution of aggregate demand should always be part of the debate but not at the expense of the growth relative to available productive capacity. At present that growth is deficient. Evidence: entrenched high levels of unemployment.

To take this out of the public sector spending is wasteful bias I would add that a lot of private spending (and production) is destructive and wasteful. All those cheap imports we now have available – plastic things that fall apart as soon as you open them etc – are wasteful in my view. But as it stands they represent jobs and livelihoods and so serve an important function.

The Fiscal Times concludes by saying:

We are in trouble, and it is time for both the left and right to discard the tired poll-tested canards that now pass as “truth” and face facts. We have work to do.

I didn’t actually read any right-wing “canards” mentioned.

The US does have work to do. The main problem is that there is no funding to make the work operational. At present, to get more people working requires higher public net spending (either through tax cuts and/or spending increases). I favour spending increases.

The poorly framed commentary is not restricted to the right however. For many years, the Dollars and Sense Organisation in the US which markets itself as “real world economics”, has been published magazines and books which aim to challenge the mainstream assumptions about the way the economy operates.

The Dollars & Sense Organisation says it:

… publishes economic news and analysis, reports on economic justice activism, primers on economic topics, and critiques of the mainstream media’s coverage of the economy. Our readers include professors, students, and activists who value our smart and accessible economic coverage.

They also publish books which question “the assumptions of mainstream academic theories and empowering people to think about alternatives to the prevailing system”.

It emerged out of the 1970s oil price shocks and was sponsored by URPE (the Union for Radical Political Economics) – the spearhead of Marxist and radical thought in America. It “sought to challenge the mainstream media’s account of how the US economy works by publishing popularly written, critical articles in an accessible format” and they say that consistent with its origins it is “still working as a collective to meet the need for left perspectives on current economic affairs”.

In its most recent editorial (August 25, 2011 edition) we read:

Public ownership of capital and democratic control over credit is the only way to avoid the veto of the bond market (being felt so painfully in Europe at the moment) …

Eek! Exactly which veto are we talking about here?

Who exactly issues the US dollar? Where does government spending come from? Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

From Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) you learn that government spending comes from nowhere and enters the non-government sector via the government crediting bank accounts in the units of currency that it issues. The bond markets do not have “money” that the government hasn’t already spent.

Governments issue debt because they are still suffering the hangover of the gold standard. It suits the conservative agenda that governments continue to issue debt unnecessarily because the neo-liberals can use the media they control to twist the public debate in their favour by misrepresenting the increase in public debt – as if it is a burden on the private sector.

If only the private sector realised that public debt is private wealth.

But below the ideological surface, MMT shows that debt-issuance is a monetary policy operation which permits the government (via its central banking arm) to drain excess bank reserves (caused by the budget deficits) and therefore allow the central bank to maintain a non-zero interest rate without offering a support rate on the reserves.

MMT categorically demonstrates that bond issuance is not a funding operation but an interest-maintenance operation conducted by the central bank. The currency-issuing government doesn’t need to fund its spending unlike a household or a business firm which uses the currency.

If a currency-issuing government wanted to increase pension cheques each fortnight by some margin they wouldn’t get the funds from the bond markets. Some computer operators in the finance departments of government would simply alter some computer program to make the increase possible. Bank credits would be increased accordingly.

Who in the world thinks that a national government consults with the bond markets before they spend. The power is always in the hands of the government. The bond markets will always have a thirst for government debt when there is no solvency risk (that is, most nations excluding Eurozone members).

The Dollar and Sense claim that the bond market has a veto is as ridiculous as the recent article (August 31, 2011) – Economist Calls Entitlements A Massive Ponzi Scheme And Says US Is Actually $211 Trillion In Debt – which quotes Laurence Kotlikoff claiming the that pensions and medicare policies were unfunded liabilities that would send the nation broke.

There is no such thing as a currency issuing government going broke in terms of commitments denominated in its own currency. Ponzi schemes only have any meaning when the originator is a currency user.

Funny about that – both Dollars and Sense and Laurence Kotlikoff are located in Boston!

So how might Dollars and Sense rationalise this apparent neo-liberal line of argument? Are they thinking that there is some political constraint?

First, the concept of a veto implies some external power – that government spending has to go before the bond markets who give it the thumbs up or down. That causality never applies to a national currency issuing government.

Second, the bond markets – which represent wealth and power typically (although many worker pension schemes are tied up in fixed income assets) – clearly do have the capacity to lobby governments. This article (August 31, 2011) – Some U.S. firms paid more to CEOs than taxes: study – provides some discussion on the power of corporate America in terms of manipulating governments.

But that is a different matter altogether – and has nothing to do with economic necessity or vetoes. The elites have always tried to defend and maintain their hegemonies. Inasmuch as we are passive they get away with it.

Third, we might be generous and assume that the Dollars and Sense editorial was pushing that line – the political rather than economic line. But then if you read further you will see that they have a very mainstream grasp of macroeconomics.

Take this recent article (August 5, 2011) as an example – Jobs, Deficits, and the Misguided Squabble over the Debt Ceiling. This article outlines a standard Keynesian “deficit dove” position.

Deficit doves think deficits are fine as long as you wind them back over the cycle (and offset them with surpluses to average out to zero) and keep the debt ratio in line with the ratio of the real interest rate to output growth.

Deficit doves are within the same species as the “deficit hawks” in that they believe that the long-term deficits pose serious risks although short-term deficits might be necessary during a recession. A standard aspiration for a deficit dove is thus to propose the government runs a “balanced budget” over the business cycle which is clearly dim-witted as a stand-alone goal and un-progressive in philosophy.

From the dove viewpoint, public borrowing is constructed as a way to finance capital expenditures. Since government invests a lot in infrastructure and other public works, those investments should at least allow for a deficit. This was already recognised by the classical economists as a golden rule of public finance.

The problem that deficit doves ignore is that the budget outcome is not autonomous – that is, a deterministic balance that is controlled by the government. The budget outcome in a modern monetary economy is endogenous and determined, ultimately by the non-government saving desires. While the government can try to reduce its deficit by cutting net spending if this runs, for example, against the desires of the private domestic sector to increase their saving ratio (assuming, say a current account deficit) then the government’s aspirations will be thwarted.

The fiscal drag will combine with the spending withdrawal of the private domestic sector (and the leakage from net exports) and the economy will contract further pushing the deficit back up via the automatic stabilisers.

It is impossible for a government in a fiat monetary system to guarantee a budget deficit outcome if it is working against the behaviour of the non-government sector.

Context is everything. The reason that the deficit dove position is unsound at the national level is because they ignore the context. For example, if a government is facing an external deficit and the private domestic sector are net saving (spending less than they are earning) then to maintain economic growth the government has to be running a budget deficit.

So unless a nation can generate significant current account surpluses, then the balanced-budget over the cycle rule that deficit doves hold out will be equivalent to aiming for the private domestic sector to be dis-saving and becoming increasingly indebted over the same cycle (to the extent that the external account is in deficit).

The average extent of this private domestic sector deficit position would mirror the average current account deficit (if a budget balance was achieved). This would be tantamount to returning to the unsustainable growth path where the private domestic sector accumulates ever increasing levels of debt. That is total idiocy and reflects a lack of understanding of the way the monetary system and the aggregate relationships between the government and non-government sector work. –

Deficit doves actually make the political case for full employment harder to make because they are held out as the “left wing” of the debate. So regression towards to mean takes us further to the right. Centrist positions now are out there a fair distance to the right and a long way from what we used to call the centre!

Anyway, back to the Dollars and Sense article. After outlining the standard Keynesian dove position you then read the following:

Why are budget deficits problematic? Deficits can cause inflation. They can also put upward pressure on interest rates, and these higher interest rates, by making borrowing more expensive, can restrict the accessibility of capital to businesses and households, which can be a drag on investment and growth. Over the long term, this sort of chronic under-investment can be substantial, as can its effects on our living standards down the road. (For the wonks and/or economics majors among you, economists refer to this as “crowding out,” as in government borrowing may crowd out private borrowing and investment). It is worth worrying about, for sure.

The “good news” is that, in this depressed economy, interest rates are extraordinarily low. Inflation is also a minor concern; indeed “deflation” is arguably a greater threat … At this moment in time, borrowing is especially easy and cheap because there are lots of potential investors sitting on big piles of cash and, further, in a depressed economy there are relatively few attractive alternatives-especially for risk averse investors.

That tells me that the Dollars and Sense “Collective” doesn’t grasp basic macroeconomics as it applies to a fiat monetary system.

First, deficits can cause inflation just like any nominal spending expansion (private or public) that drives nominal (money-value) aggregate demand beyond the real productive capacity of the economy to absorb it and respond to it in real (output) terms.

But budget surpluses can also cause inflation in the same way. Take a case where there is a booming net exports sector and the private sector is not saving. Then if the budget surplus is too small total aggregate demand growth might outstrip real productive capacity. The only constraint the government faces in terms of its spending capacity is the real productive capacity. Obviously, when there is significant idle capacity that constraint is not binding at present.

Second, how do deficits put upwards pressure on interest rates? The dynamic is the reverse. The deficits add to bank reserves which stimulate competition among the banks to reduce their excess reserve holdings which pushes rates down (in the absence of a support rate being paid by the central bank).

The Dollars and Sense quote reads like it comes out of a mainstream macroeconomics textbook – using terms like “crowding out”. The causality in those models is that the government spending competes with private uses for finite “savings” in a loanable funds market, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

At the heart of this erroneous hypothesis is a flawed viewed of financial markets. The so-called loanable funds market is constructed by the mainstream economists as serving to mediate saving and investment via interest rate variations.

This is pre-Keynesian thinking and was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

So saving (supply of funds) is conceived of as a positive function of the real interest rate because rising rates increase the opportunity cost of current consumption and thus encourage saving. Investment (demand for funds) declines with the interest rate because the costs of funds to invest in (houses, factories, equipment etc) rises.

Changes in the interest rate thus create continuous equilibrium such that aggregate demand always equals aggregate supply and the composition of final demand (between consumption and investment) changes as interest rates adjust.

According to this theory, if there is a rising budget deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending.

So allegedly, when the government borrows to “finance” its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. The mainstream economists conceive of this as the government reducing national saving (by running a budget deficit) and pushing up interest rates which damage private investment.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost self-evident truths. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

Further, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. But government spending by stimulating income also stimulates saving.

Dollars and Sense might reply and say they didn’t imply this causality. But why would they say “For the wonks and/or economics majors among you, economists refer to this as “crowding out,” as in government borrowing may crowd out private borrowing and investment”. That is an appeal to the mainstream myth.

They could argue that the central bank might increase interest rates because they fear that the budget deficits will add to inflation. That is just an acknowledgement that central banks set the interest rate. Interest rates rise when there are budget surpluses and often fall when there are budget deficits. In other words, there is no empirically robust relationship ever been found to show that higher budget deficits are always associated with higher interest rates. Part of the reason for that lack of relationship is the fact that the budget deficit can rise when times are bad (via the automatic stabilisers).

Further, there is scant evidence to show that the sensitivity of investment to changing interest rates is high independent of expected earnings streams. When aggregate demand is high enough for the central bank to start hiking rates, profits are normally buoyant and earnings strong which encourages more investment.

Conclusion

I admire organisations that try to run counter to the mainstream and improve the lives of ordinary people. But in the case of Dollars and Sense, their macroeconomics input leaves a lot to be desired and they become part of the problem rather than part of the solution. They often, for example, rely on Paul Krugman as their “progressive oracle” – a big mistake.

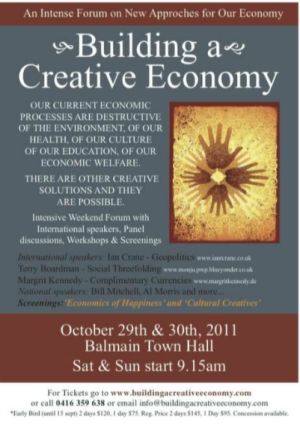

Upcoming Conference

I agreed to speak at this Conference – Building a Creative Economy which might be of some interest to readers. The Conference is being held in Sydney on the last weekend in October. I am talking on the Saturday of the two day event. I expect there will be some interesting discussions although this is not a MMT conference.

The Conference is a grass-roots effort and is trying to promote alternative ways of thinking about the economy and our lives which sit with social justice and environmental sustainability. It deserves support for that reason if nothing else.

That is enough for today!

“It [Dollars and Sense] emerged out of the 1970s oil price shocks and was sponsored by URPE (the Union for Radical Political Economics) – the spearhead of Marxist and radical thought in America.”

I have a lot of time for Marx as an economist but I was reading some of the old American Marxists the other day (Sweezy, Baran, Magdoff etc.) and they’re just neoclassicals that draw weird conclusions.

Example: they claim that the high-interest rates in the early 1980s were correlated with the deficit and there was some sort of causal link — they don’t state what, they’re very vague on this point. Then they note that high deficits were accompanied by low-interest rates in the WWII era. So, what’s their explanation. Erm, an ‘expanding finance sector’. Yeah, no mention of the Volcker shock or tackling inflation — an ‘expanding financial sector’ is to blame… someone… even though they don’t make clear how. (‘Economic History as it Happened: Vol. IV’)

As far as I can see a lot of Marxist economists just take the worst elements of Marx — the ‘supply-side’ conclusions that you CAN draw from his work (and are, in a sense, encouraged to) — and claim that capitalism is inherently evil. That’s it. You draw out the worst aspects of neoclassicism while keeping within that frame — and then promise Communism and revolution will solve everything.

Annoying.

Regarding:

“It is clear that the conservatives do not have a growth agenda and are using their power (media, corporate etc) to white ant the nascent, fiscal-driven recovery for their own purposes.”

“White ant”? Not familiar with this term…

Dear Dale

White ant = undermine

As in the white ants that invade houses and eat away the wood frame and beams etc.

best wishes

bill

@Dale

Termites are called white ants in Australia.

“Mark Thoma who often claims MMT is simply wrong but refuses to debate that claim”

Observing mainstreamers’ struggle with MMT (Nick Rowe and Scott Sumner are good examples, Krugman to a little extent) I see a pattern (and not a very smart one):

1. They cook up an argument critiquing MMT

2. They are proven wrong or that they misrepresented MMT

3. They call MMT a cult and a bunch of idiots.

1. They cook up an argument critiquing MMT

2. They are proven wrong or that they misrepresented MMT

… and so it goes.

Thoma simply saves everybody time and sticks to #3.

Bill,

Thanks again, as usual.

You have written pretty extensively against government issuing debt unnecessarily, given that monetary sovereignty exists in a fiat money system, among other reasons.

It may be worth mentioning that the government here does not issue the currency – our money supply is issued, and reclaimed, as bank-credit by private bankers at their motivation and to their benefit, acknowledging at the same time the tenet of MMT that this is merely a self-imposed constraint BY the ignorati, we the sovereign peoples and our government.

Again, whereas in the “real-MMT” world, the government does not need to borrow to fund its deficits, the GBC presently mandates that there is a taking through taxation or a debt-issuance OF EXISTING MONIES to balance government spending.

Regardless, we do not HAVE currency-issuing governments.

Defending government debt-issuance as a necessary measure for managing interest rates and reserves remains a prop to the fractional-reserve banking system that all progressives should abhor on its surface. The privileged class of bankers that get to create their assets out of nothing and collect rents from the masses, ending here at debt-saturation, should be on every progressively minded person’s chopping block as number-one.

Thus, and only thus, do I agree with the Dollars and Sense observation –

“Public ownership of capital and democratic control over credit is the only way to avoid the veto of the bond market …” – more correctly – the blatant power of the bond marketeers over our government.

You quasi-defend increasing government indebtedness as a necessary evil to manage the dictates of the fractional-reserve banking system. To which I say, resort to a full-reserve system not only removes the moral hazard of government backstopping the bank excesses that Minsky lays at the base of financial instability, but it also removes any mechanistic necessity for a central bank role in stabilizing or managing interest rates and reserves.

With adequate money in existence along with full-reserve banking, we resort to the ‘natural’ interest rate and allow supply and demand(the market) for loans to determine interest rates.

In the “unreal” non-MMT world, not only do bond markets have money that the “government” has not created, i.e. bank-credit-money, but also, through their shadow and non-bank structures, they create monetary assets – things that serve as money – in various levels of “junk” that have the power to topple the real economy, as we have already seen and are now feeling. Reform of the monetary system must include ending the non-bank and non-money charade.

So, speaking of reforms, as I asked at the Teach-In, where is the list of legal constructs that DO exist and DO drive political reality today, due to the ignorance or misunderstanding of the rest of the world, that we would need to change in order to have the awakening to a system that MMT theorizes is possible?

MMTers, including brother Warren who runs for all political office in order to propound MMT ideals, like to say they only theorize and postulate an unrecognized macro-economic monetary structure that IS. The others say they do not organize and they are not activists. But until someone sits down and lays out the legislative proposal to turn MMT into the legal reality of the day, well, the broad goals of full-employment and economic democracy will remain on the theoretical shelf, eluding us all.

Maybe another, With Friends Like These…

Thanks for everything, Bill.

PS Including, for anyone who doesn’t have it, the new Pressure Drop release.

“resort to a full-reserve system”

A full reserve system doesn’t help unless the discount window at the central bank is closed. And that means you have to be prepared to put banks into administration for cashflow issues rather than just running out of capital. Which probably means banning maturity transformation as well.

You cite the following as a “left-wing myth” (arguing, I presume, as someone on the left):

3. “… the wealthy should pay a little more.”

“…They take it as written that there is a debt problem but then argue about who should pay to fix it up.

“Such arguments play in to the hands of the conservatives. They are not germane to the current problems facing the US. At present, the only reason you would want the high income earners to pay more would be on equity grounds. There is no inflation threat and an urgent need for higher aggregate demand. Raising any taxes is contra-indicated.

“So if you wanted to raise the taxes on the rich now you would certainly be looking for expansionary measures to ensure that the budget deficit increased. There is always the capacity within fiscal policy to increase spending while changing its composition (across sectors and income cohorts). That is the beauty of fiscal policy as a counter-stabilisation tool.”

I agree entirely with your last paragraph on the necessity of expansionary fiscal policy, but you underestimate the harmful economic effects of wealth inequality — and the economic arguments for for higher taxation, not merely on “equity grounds.”

High wealth inequality produces insufficient aggregate demand. Since paying down debt is obligatory, aggregate demand won’t increase until deleveraging (“saving” not consuming) occurs in the mass of households. In the interim, insufficient taxation of high wealth feeds surplus saving (“hoarding” in safe assets) or speculation (asset inflation without new production). For this reason, I also think you underestimate the inflationary effects of QE:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/aug/14/quantitative-easing-riots

http://www.cnbc.com/id/43237587/El_Erian_Why_Fed_Is_Unlikely_to_Have_Third_Round_of_Easing

As you point out, the money needs to be spent by the government in targeted fiscal policy which, essentially, redistributes wealth toward debt re-payers and aggregate demanders (not holders of safe assets or asset speculators). A great economic opportunity was lost when vast amounts of debt was re-secured via the bank bailouts in the U.S. Now that will all have to be deleveraged by households, rather than written off by investors. That will delay recovery.

It seems to me that MMT’s macro-analysis needs to be fleshed out with a “semi-macro” (effects of wealth stratification) analysis (especially as it affects hoarding and inflation of, e.g., commodities) and a (macro-, semi-macro, micro) balance-sheet analysis (e.g. Richard Koo).

They’re not inconsistent with MMT — except when MMT suggests that wealth redistribution (and, by extension, debt forgiveness) is only a question of equity. They make good economic sense.

“If only the private sector realised that public debt is private wealth.”

Once again:

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t (preferably with debt) plus dissavings of the lower and middle class (preferably with debt)

joebhed said: “Regardless, we do not HAVE currency-issuing governments.”

Yes! And, is that one reason central banks exist?

Ron T said: “”Mark Thoma who often claims MMT is simply wrong but refuses to debate that claim”

Observing mainstreamers’ struggle with MMT (Nick Rowe and Scott Sumner are good examples, Krugman to a little extent) I see a pattern (and not a very smart one):”

Ron T, if you ever get the chance, ask these “examples” if they can tell the difference between what I would call “currency” and “debt”. I’d like to know what they say.

Neil Wilson, joebhed, Ron T, and anybody else:

Why not have a zero debt (both private and gov’t) economy? It seems to me that would give the best chance(s) of distributing productivity gains and other things evenly between the major economic entities AND evenly in time.

joebhed,

“Regardless, we do not HAVE currency-issuing governments.”

I understand the point you are making here, and yes mandates like that should not exist, but I still think that from a technical stand-point one could argue that the government still issues the currency, but the CB is mandated to convert this to bonds unnecessarily. Even if you interpret the mandate to mean that the spending happens after the issue of bonds, it would still be converting govt issued currency from the previous period.

Anyway, the correct thing to do would be to remove the mandate and regulate (or nationalise) the banks. Ending FRB would not be necessary perhaps. In the UK a new committe in the Bank of England has been set up which will utilise old laws (abandoned in the monetarist period) allowing it to regulate bank lending. It is called the Financial Policy Committe. I don’t know how effective it would be though.

Let me ask a kind of devil’s advocate question. I challenge anyone to answer it.

If MMT is substantially correct about the economy under fiat currency conditions (and I consider it is);

If Keynes, Marx and Minskey (to name 3) are among the best historical analysts of capitalism;

If the Limits to Growth theory of Meadows et al is substantially correct (and I consider it is);

If these thinkers have been marginalised and ignored by the main stream, the media outlets and the public;

If being so ignored has been fate of all our best thinkers who sound verifiable warnings; and

If this has been consistently the case since the advent of empirical science;

Then what hope have we now to change this picture and for the first time in history get the mass of humanity to listen to science, logic, reliable prediction and prescriptions for action based on conclusions from the empirical method? I would suggest the chance is zero. The system will roll on to its doom with humans being just as stupid, short-sighted, greedy, selfish and cruel (en masse) as they have always been.

I would be intrigued if anyone can draw a different conclusion from mine and suggest why I am wrong and what are the fallacies in my above argument.

Dear Joel Bernard (at 2011/09/02 at 2:49)

You stated:

To be clear – these were quotes (all four “myths”) – from the Fiscal Times article. They were not my own statements. I was putting them in a context.

best wishes

bill

Perhaps a better article by Liz Peek would have been “Confessions of a TARP Wife, which though unsigned, was found to be written by Liz. [“Forget the opera. Cancel dinner at Bouley. How life has changed since my CEO husband went on the government dole.]

Or maybe you simply could have said that she’s a frequent “contributor” to Fox?

joebhed,

I would like to know what you mean by “full reserve banking”. I agree with Neil – I don’t think changing the reserve requirement to 100% will accomplish what you believe it will, so I think you must mean something other than “full reserve banking”.

Jeff

Ikonoclast,

history is full of paradigm changes in the economic policy. Before great depression it was mercantilism, after it it was Keynesianism until 70s, and after that it was monetarism until recently. Undertanding and arguments about economy have improved constantly. Problem has been that in the good times there have not been lot of debate going on. Unfortunately people do not feel motivated to argue these issues if there is no crisis. Crisis has opened opportunity for yet another paradigm change, and, unfortunately, one of the risks are that it would go away too easily to get trough any meaningful changes.

Below are figures for UK bank reserves BL22 during the financial crisis in millions.

You can see the effect on reserves of 200 billion of QE from March to November 2009

Without QE you might have expected reserves to hit say 50 billion by now. With it 250 billion

My question is, assuming UK borrows to cover its deficit and PFI spending, does the difference between the 250 billion and the actual July 11 figure of 127 billion represent a reduction in private debt?

31-Jul-08, 27942

31-Aug-08 28696

30-Sep-08 36309

31-Oct-08, 48367

30-Nov-08 45621

31-Dec-08 43098

31-Jan-09, 40425

28-Feb-09, 39467

31-Mar-09, 40758

30-Apr-09, 71314

31-May-09 98689

30-Jun-09, 125383

31-Jul-09, 152083

31-Aug-09 142932

30-Sep-09 137382

31-Oct-09, 143626

30-Nov-09 148830

31-Dec-09 145830

31-Jan-10, 153796

28-Feb-10, 156405

31-Mar-10 , 152275

30-Apr-10, 151883

31-May-10 150950

30-Jun-10, 149737

31-Jul-10, 150051

31-Aug-10 150370

30-Sep-10 144380

31-Oct-10, 143153

30-Nov-10 143494

31-Dec-10 139953

31-Jan-11, 139245

28-Feb-11, 138500

31-Mar-11, 135420

30-Apr-11, 132537

31-May-11 131523

30-Jun-11, 128903

31-Jul-11, 127196

@joebhed

Ah, an Austrian-school libertarian like my dad!

You do realise that since any record of a debt can function as money, what you are really proposing is a return to a barter system, with money being just another commodity? That you would need to abolish all ‘money-like’ instruments of trade; cheques, invoices, 30-day terms, payment on account, bar tabs, along with mortgages, personal loans, and derivatives?

Because as soon as you start allowing people to create and accumulate non-money financial assets they will, and there goes your ‘loanable funds’ market (again). And if do somehow succeed in stopping people ‘paying it forward’ by incurring debts, back we go to subsistence poverty.

“does the difference between the 250 billion and the actual July 11 figure of 127 billion represent a reduction in private debt?”

I don’t think so, because the banks have been using this stockpile to buy government gilts on the primary market, so you need to look at the holding of gilts by banks over the same period to get the full view on the vertical position.

The general theory going around is that banks are outbidding the rest of the private sector on gilts, but then providing their own saving products to fill the demand for saving. (Which is more evidence that gilts are pointless).

The stats at the ONS are complicated by the fact that they roll the Bank of England into the Private Banking sector. It makes it very difficult to tease out the position on vertical liabilities.

“I don’t think so, because the banks have been using this stockpile to buy government gilts on the primary market, so you need to look at the holding of gilts by banks over the same period to get the full view on the vertical position.”

But does it matter if the banks are buying up the primary debt? They would have anyway wouldn’t they? and the net result is the same assuming my assumption that pound for pound deficit spending is ‘borrowed’ holds i.e. it shouldn’t affect the overall reserve position

Bill,

On the website it says that you are presenting on the Sunday (30th) at 2:15pm. Above you stated that you are presenting on the Saturday.

Apart from that, the conference looks interesting. It fits in well with my assessment schedule, so I may see you there.

Andy,

The only thing that can eliminate bank reserves is taxation not the elimination of private debt. Private debt is a horizontal transaction.

In theory government excess spending is matched with gilt issue so there shouldn’t be any increase from that direction (which as you rightly point out should soak up the primary gilt market), and taxes should be paid from the rest of government spending in that period.

The BL23 time series gives you the change in reserve balances which appear to be down about £23 bn over the last year.

So its a bit of a mystery to me where those have gone. The only thing I can think of is repos expiring where the bank has to return some money to the central bank which was secured against gilts they already held.

The balance sheet graph here for the Bank of England shows the other side of the transactions.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/images/liabilities_assets.jpg

Andy, Neil,

My understanding is that, consistent with the fact that the broad money supply is endogenous and driven by demand for credit, If in a particular period the banking system as a whole lends more principal than the the amount of principal repaid (bank net-lending), it is logical that system-wide reserves should also increase in that period.

Dear mdm (at 2011/09/02 at 17:32)

The program is currently not updated. I am speaking on the Saturday at around 14:00 and then on a panel until about 17:00.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Neil & Charles

I think I need to revise my understanding of reserves. I had assumed that when private debt was repaid, the deposit used to repay disappears along with the debt and that bank reserves are reduced by the same amount. Also that when banks lend, they create deposits and reserves are increased by the same amount.

There is something, probably bloody obvious to everyone else, I’m missing.

Andy,

The reserves don’t change. They are simply not required until a customer draws on a deposit for payment at a different bank.

A loan advanced is simply:

DR Loans advanced

CR Customer deposits.

and that’s it.

Neil. Got it. Thanks. Now I need to re-read some 101 blogs.

Andy, reserves get created when the Treasury spends into non-government. The Treasury obtains the reserves for settlement from the cb. Reserves transferred to banks through settlement of govt. expenditure get drawn down by taxation. Deficit spending (addition of reserves in excess of withdrawal by taxation) creates excess reserves in the settlement system, which must be neutralized if the cb desires to set an overnight rate in that system greater than zero. This requires that either tsy issuance to drain excess reserves, or payment of interest on reserves (IOR) by the cb.

In the case of tsy issuance instead of IOR, the tsys act as a buffer that the cb uses to adjust available reserves to bank needs in a way that allows maintaining the target rate. The cb does this through open market operations (OMO) by converting tsys to reserves and vice versa as changing conditions require. In addition, if banks need reserves they can repo tsys at the cb to obtain them, or use the discount window and pay a penalty rate. This switches tsys to reserves and back iaw operational requirements and pursuit of optimal return.

Loans create deposits, which require reserves for settlement as they are drawn upon. Banks cannot create reserves themselves, but must obtain them by getting deposits that transfer reserves to them in settlement, borrow them from other banks in the interbank market, or obtain them from the cb either through repo or at the discount window.

Some say that “deposits create reserves,” which is true in a way, but this can give the wrong impression. Deposit don’t actually create reserves in the way that the cb does and only it can do. Customer deposits draw reserves to the banks reserve account (or add to vault cash in case of cash deposits, which the bank can exchange for reserves at the cb). Loans creating deposits necessitate the bank obtaining reserves from other banks or the cb to meet reserves requirements and clear its liabilities as necessary in the interbank market as deposits are drawn down. Banks create deposits through extending credit (“inside money,” endogenous, horizontal), but they cannot create reserves, which constitute “outside money,” exogenous, vertical.

Tom Hickey said: “This requires that either tsy issuance to drain excess reserves, or payment of interest on reserves (IOR) by the cb.”

What about raising the reserve requirement?

Let me see if I have this straight.

With private debt and when the recipient’s demand deposit account is marked up, there is no 1-to-1 reserve account markup. So, when the private loan is “attached”, there is no 1-to-1 reserve account markdown. Correct?

With gov’t debt and when the recipient’s demand deposit account is marked up, there is a 1-to-1 reserve account markup. So, when the gov’t loan/bond is “attached”, there is a 1-to-1 reserve account markdown. Correct?

Fed Up,

“What about raising the reserve requirement?”

Doesn’t work. If the discount window is open and the central bank is targeting a rate then they just have to supply the amount of reserves required for the system to clear. Either side of that the rate plunges to zero, or goes sky high.

ISTM that the reserve requirement just increases the amount of government subsidy going to banks if there is a positive interest rate.

Confession time

Over the last few months I had built up a nice cosy little picture of MMT that turns out to be false.

In my MMT world somehow all deposits existed in member banks’ reserves with the central bank (not necessarily the same bank as the depositor’s)and were increased by deficit spending and private lending and reduced by taxation, government debt issue and repayment of debt.

A mere look at the numbers would have put me straight.

So now, if I have it straight, reserves are there for settlement only as far private banks are concerned but can be used by government for to carry out both monetary and fiscal policy.

Central banks are not as powerful as I thought they were. Private banks are more so. I understand now why Bill has stated many times that central banks can’t control lending.

God knows how I got the notion that loans create deposits create reserves but If I did I’m sure others did also.

Fed up

“Let me see if I have this straight.”

It seems that you’re looking at it from a strange angle and missing some intermediate transactions.

When anybody receives anything from a third party bank (public or private) the transaction is the same from the recipient’s private bank’s point of view – Bank Reserves go up and Customer deposits go down (remembering that customer deposits are a liability of the bank). (DR Bank Reserves, CR Customer deposits)

You can simplify money creation to an overdraft which is essential just a positive number in a customer deposit account from the bank’s point of view (remembering that deposits are bank liabilities and overdrafts are bank assets). So private debt is really just a load of positive Customer deposit accounts.

Now private banks are customers of the government sector and their bank reserves are just customer deposit accounts from the government sector’s point of view. The same balance sheet expansion process applies there. Payment simply marks the government’s own deposit account up and the private bank’s deposit account with the government down (again remembering that private bank deposit accounts are a liability from the government’s point of view). That then causes a payment in the private bank’s accounts (bank reserves up, customer deposit down).

The public debt can then be said to be simply how much the government deposit account with itself is overdrawn and since it owns or controls the central bank that makes the public debt an equivalent asset from the government sector’s point of view.

And that is why the government neither has, not has not any money – because the debt and the asset are always equivalent and cancel each other out.

So private debt is effectively positive customer deposit accounts at a private banks and public debt is the government’s positive customer deposit account with the government.

Public debt payment

Government

DR Government’s deposit account

CR Private bank’s deposit account

Private Bank

DR Bank reserves

CR Recipient Customer Deposit

Private Debt Payment – interbank

Bank A

DR Borrower Customer Deposit

CR Bank Reserves

Government

DR Private Bank A Deposits

CR Private Bank B Deposits

Bank B

DR Bank Reserves

CR Recipient Customer Deposit

This ignores that private savings often means money removed from the economy. Most people save, then spend the money after they retire, but wealthy people just accumulate money which means goods and services forgone. Higher taxes on the wealthy are just forced spending, bringing that money back into the economy. Yes, the government can simply borrow instead, but they would have to fight this damper on economic action.

Wow, been away.

Pobably too late, but…

uummm, Begruntled – no, not an Austrian or Libertarian, I am a progressive monetary student.

It’s a pity that those who would broad-brush with their own ignorance a position that is widely recognized as a most progressive position – that of full-reserve banking is limiited to right-leaning politics for the simple reason that it is correct, macro-economically speaking.

Read-up on the Chicago Plan for Monetary Reform and the Monetary Control Act of 1934.

Read up on the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform.

These were the most rogressive political economists of their time.

The author of 100 Percent Money , Irving Fisher, is widely recognized for his efforts to restore economic, financial and monetary stability, especially hen we abandoned the gold standard.

I advocate for the system proposed by Dennis Kucinich

http://kucinich.house.gov/UploadedFiles/NEED_ACT.pdf

Perhaps you think of him as an Austrian.

It does abolish all those faux-money aspects of financialization that you mention.

Nothing serves as money except money, all created through the government paying it into existence, once full-reserve banking is achieved.

Just like the MMters do through Fiscal Economic Sustainability

One would thin that Bill’s students were better informed.

Sorry.

Jeff said:

joebhed,

I would like to know what you mean by “full reserve banking”. I agree with Neil – I don’t think changing the reserve requirement to 100% will accomplish what you believe it will, so I think you must mean something other than “full reserve banking”.

Neil Wilson says:

“resort to a full-reserve system”

A full reserve system doesn’t help unless the discount window at the central bank is closed. And that means you have to be prepared to put banks into administration for cashflow issues rather than just running out of capital. Which probably means banning maturity transformation as well.

Neil followed my discussion of full-reserve banking at Rodger Mitchell’s site months ago.

I am starting to believe that MMTers have a blind spot when it comes to full-reserve banking, despite the fact the BoE Governor Mervyn King recently (Buttonwood Gathering) recommended same as a means to end the boom-bust economic cycle.

Full-reserve banking works whether the discount window is open or not, but the Kucinich proposal closes the discount window and all other interest rate and reserve management CB functions.

Like I said in my comment, GIVEN adequate money exists to achieve all the MMT goals, there is no need to manage interest rates at all. The Fed manages interest rate in a string-pushing mechanism to control the money supply and therefrom inflation.

Then Neil claims that closing the discount window somehow means you need to put banks into “administration” for cash-flow purposes.

Gawd.

With full-reserve banking, the regulation of ALL banking become minimal for the reasons I stated.

Banks without adequate cash-flow would fail, because deposit insurance would not exist – no moral hazard.

Then Neil adds – “which means banning maturity transformation as well”.

Huh?

Banning maturity transformation?

Whereas maturity-MATCHING will become the high mark of sound banking, I don’t even know what ‘banning maturity transformation’ means.

Banks would be free to make any term loans they want.

But the would have to be ‘fully-reserved’ at all times.

If the bank does not have the money, then the bank cannot lend it.

On to Jeff’s point about what do I mean, I suggest a read of the Kucinich Bill- again:

http://kucinich.house.gov/UploadedFiles/NEED_ACT.pdf

But, more importantly, read the Central Bank Chapter on Reserve Requirements in Ritter’s Money and Economic Activity – written by progressive economist Irving Fisher, author of both the 100 Percent Money book and the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform.

My one sentence description would be thus:

Full reserve banking means the real monetization of “demand-deposits”, the result of which is that all money in banks is real money, and upon that transformation, banks cannot lend M1-type demand-deposits, and can only lend the money that depositors receive interest on.

The result is monetary stability.

Again, read the Kucinich Bill for the mechanism.

Thanks.

To Charles J.

I agree that government bonds are funded with previously issued dollars, but not that those were of “government-issue”. Those were of private bank credit issuance.

I don’t agree at all about nationalizing the banks – banking is properly a private activity. But issuing the national circulating medium is a government function, and should be restored to ‘we the people’. Thus it is the nationalization of the money system that is needed.

Once you nationalize the money creation process, FRB is history, all in one swell foop.

Banks are bankers, and government governs.

As to the effort underway in GB, please google the PositiveMoney.org submission to the FPC.

Thanks.

joebhed,

I don’t believe MMTers necessarily have a blind spot with regard to “full reserve banking”. The term means something specific in the context of the system we already have. If someone wants to give the term an entirely new meaning perhaps they should expect to be repeatedly misunderstood. I’m not claiming you’ve done this as I expect this is what other people have named these proposals, but they are misnamed.

I haven’t looked at the specific proposals you refer to, but it has been my experience that proposals turning the banks into maturity transformation entities come from people who misunderstand the nature of credit. Banks’ special power is not credit creation – any entity can do that; think of your JC Penney credit card or the “no money down” offers you see everywhere. The special power of a bank is access to a statutory payments system (the Fed, etc. were created by an act of federal law) that makes bank created credit good everywhere.

The problem is that:

1) The govt grants access to the payments system too cheaply; it could insist the bank follows any rules it wishes. A good rule I can think of is to not allow banks to sell loans they have originated.

2) The rules that are in place have been routinely ignored; Lehman should not have been the only bank to end up in resolution.

Apologies if this mischaracterises the nature of the proposals you mention.

Cheers,

Jeff

joebhead,

The problem you are missing, and the entire full-reserve proposals miss, is that banks cheat. That’s how fractional reserve banking came about in the first place. And there is huge incentive to cheat given that it allows you to beat the market with leverage.

So if the discount window is open then banks can get reserves after the fact and you end up with the same system we have now, just with a pile of cash or reserves on the accounts rather than a state insurance policy.

Full reserve only works if the banks have to say at some point ‘sorry we’re full’ and go bust if they run out of money.

Full reserve is not a free market banking nirvana.

To Neil Wilson

I guess you REALLY do not get, so I apologize for saying that you do.

If you followed my lengthy discourse with Rodger Mitchell, in which you commented, you would not make this statement:

“So if the discount window is open then banks can get reserves after the fact and you end up with the same system we have now, just with a pile of cash or reserves on the accounts rather than a state insurance policy.”

?? GET reserves??

Sorry, in a fully reserved system, and I have already given the references here and elsewhere, there is no place to GET reserves.

ALL MONEY IS REAL MONEY, after the monetization of bank credits to full-reserves.

There is no NEED for reserves as their is no lending against any portion of reserves.

Why not read the Kucinich Bill and say how the banks would be motivated to attempt to acquire reserves after all former “fractionally-reserved” monies become real money through the real-monetization process?

It is NO DIFFERENT than as was laid out in the 30s by Irving Fisher and as is contained in many economic textbooks in their treatment of central bank reserves.

The discount window is obviously not open, and the central bank resorts to operations that do NOT affect the money supply at all.

You’re a little closer to the truth with this statement:

“”Full reserve only works if the banks have to say at some point ‘sorry we’re full’ and go bust if they run out of money.””

But only a little.

Every bank will want to lend out all of its investment and savings deposits – fully.

When that happens, they do not go bust – they prosper.

Since banks make money on their interest rate spreads, how can lending out all their money – maximizing their profit potential – mean they go bust?

How do you dream this stuff up?

Sorry, Neil, this is EXACTLY what I mean about MMT blinders on full-reserve banking.

Please stop pretending that it is not understandable.

Google up the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform.

tely

Jeff

Jeff,

Cheers, backatcha.

You say ‘full-reserve banking’ means something within the context of the system that we already have, perhaps something different from what I mean.

What does it mean?

When Bank of England Governor Mervyn King says we need to consider “full-reserve banking’ as a means to restore financial and economic stability, he means the same thing that I mean – which is the same thing that Irving Fisher(Yale), Henry Simons(Chicago), Charles Whittlesey(Princeton), Paul Douglas(Chicago), Earl Hamilton(Duke), Wilford King(NYU), Frank Graham(Princeton) Frank Knight and Aaron Director(Chicago) and Lloyd W. Mints – author of The History of Banking Theory mean by the term.

These were all among progressive economists supporting full-reserve banking, as well as, on the conservative side, Milton Friedman’s proposal in his Fiscal and Monetary Framework for Economic Stability.

Their full-reserve proposal was intended as the necessary step to end what they called “the lawless variability in the supply of our national circulating medium”

(From the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform – a document PUBLICLY-supported by over 400 economists at the time.).

I do not accept the implication that it is me that is trying to give the term “full-reserve banking” new meaning other than what you may think it means today.

I ask you to explain what you think it means, and provide me some reference for that meaning.

It is EXACTLY that bank power to CREATE things that serve as money that would necessarily end with full-reserve banking. So, we need a new federal law to replace the Fed Act, and we have one here:

http://kucinich.house.gov/UploadedFiles/NEED_ACT.pdf

Please have a read.

Cheers.

joebhed,

Clearly these proposals are misunderstood today due to the misleading name “full reserve banking”. This, to me and others, implies that you want to change the reserve requirement to 100% which will accomplish almost nothing on its own. It doesn’t imply the other stuff (doing away with the central bank, etc.)

Can you offer a descriptive link that offers more than “full reserve banking” but is easier reading than the bill? I’d be particularly interested to know how such a system deals with these issues:

1) not having a central bank (how does the payment system work?)

2) how do we fund ideas after the banks have loaned out all time deposits? (do we have to wait for grandma’s term deposit to mature to free up funds to pursue an idea that seems likely to lead to a cure for cancer?)

3) how do you stop people and businesses from offering store credit? (if banks as they exist today lost access to the payment system they could continue to create credit – the created credit could be used to pay other customers of the same bank)

These proposals stem from the idea that private credit creation is inherently bad. The fact that it is the basis for the earliest forms of money contradicts this idea. Instead it seems to say that it is inherently good.

joebhed,

Then the discount window is closed in your suggestion. Sorry but above you said “Full-reserve banking works whether the discount window is open or not” and I was clarifying that.

And what happens when banks cheat – which they will since that is how fractional reserve came about in the first place?

Jeff,

The term ‘full-reserve banking” SHOULD imply changing the reserve requirements to 100 percent. To say it would accomplish nothing is a little gratuitous on your part.

Noted monetary economist Irving Fisher writing in his 100 Percent Money proposal, sometimes called 100 Percent Reserves and full-reserve banking, lists the following advantages:

1. The end of bank runs on commercial banks.(no FDIC-based moral hazard today)

2. Therefore, Fewer bank failures.

3. Reduction / elimination of government debt.

4. A simplified money system – all of our circulating medium would be actual money.

5. The banking system would be simplified – as between what is a demand deposit and a savings/investment deposit/loan.

6. The basis for great inflations and deflations, therefore booms and busts, would be eliminated – stabilizing and leveling the business cycle.

7. Banks would no longer control industry – they would NOT be the source for money, only for loans.

I didn’t mean to imply the end of a national central bank, just that many of today’s central bank functions could be eliminated. A public central bank still performs clearing , supervisory and regulatory functions for the banking industry, and makes loans to bankers if needed.

As far as offering a ‘descriptive link’ that is easier to read than the Bill, I see the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform as the best proposal. It includes but is not limited to full-reserve banking.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Program_for_Monetary_Reform

1) not having a central bank (how does the payment system work?)

Remains the same, with the nationalized Fed under Treasury.

2) how do we fund ideas after the banks have loaned out all time deposits? (do we have to wait for grandma’s term deposit to mature to free up funds to pursue an idea that seems likely to lead to a cure for cancer?)

That’s cute, Jeff – bringing in Grandma and curing cancer. It’s the grandkids, and preventing cancer you should be thinking about here.

If there is adequate money created, and we have monetized the exiting demand deposits exactly where they are located – the banking SYSTEM will not run out of money and the normal inter-bank lending provides for locational liquidity needs.

Also, under the Bill, which you should read selectively to answer these questions -these are the duties of the Federal Reserve Bureau after it has been integrated into DoTreasury.

From Section 303 of the Act:

Federal Reserve Bureau

(c) DUTIES.-

(1) MONETARY POLICY.-The Bureau shall-

(A) administer, under the direction of the Secretary, the origination and entry into circulation of United States Money, subject to the limitations established by the Monetary Authority; and

(B) administer lending of United States Money to authorized depository institutions, as described in section 403 (‘Revolving Fund’) to ensure that-

(i) money creation is solely a function of the United States Government; and

(ii) fractional reserve lending is ended.

(2) TRANSFERRED FUNCTIONS.-After the effective date, the Bureau shall exercise all functions consistent with this Act which, before such date, were carried out under the direction of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

______________________________

3) how do you stop people and businesses from offering store credit? (if banks as they exist today lost access to the payment system they could continue to create credit – the created credit could be used to pay other customers of the same bank)

Hopefully there will be MORE store credit. Store credit does not create any money. I assume the store accepts already-created United States Money in payment for the customers’ debts. They might also accept local exchange instruments – OK with me.

These proposals stem from the idea that private credit creation is inherently bad.

OK, Jeff. You’re intelligent.

Have you watched this video? http://blip.tv/file/4111596

The top half of the equation is the credit money(IOU) that is created. : $10 Trillion

The bottom half is the debt-service-payments-due(U-O-ME) – the debt part. $20 Trillion.

When you borrow (necessarily) $1,000 and need to pay back $2,000 – but only $1,000 has been created – Is that inherently bad?

Try to understand both Dr. Senf’s observation about ‘the fog around the interest’, and his 5 socio-economic crises that result from that fog.

The fact that it is the basis for the earliest forms of money contradicts this idea. Instead it seems to say that it is inherently good.

Gawd, anecdotal guidance here.

First of all, you are totally wrong – all of the earliest forms of money were, by necessity, fully-reserved.

The gold exchangers had ONLY the gold to trade.

Only when the gold traders started trading ‘receipts’ in excess of their gold-holdings, did the illegal and immoral practice of fractional-reserve banking come into existence.

Neil.

Thanks.

First, yes, in the Kucinich Bill, almost every ‘discount window’ transaction involving the sale of government securities is ended. There is still the need for discounted overnight liquidity. Most of that would be an inter-bank function. But the new FRBureau can still lend to banks for any reason as necessary – just that it would not ever affect reserve status.

Second, yeah, thanks for clarifying for Jeff that it was the cheaters at the gold exchanges that conceived of fractional-reserve banking.

In today’s world, under a reformed money system, where the books of the bankers are basically open electronically to the regulatory authorities, I don’t see how cheaters can be very successful for long.

If your observation is that TONNES of fraud have gone unpunished in recent years, that’s mainly due to the unregulated, wildcat quasi-banking, near-monied environment that we have been living in.

There is a bank balance sheet.

It’s cash-reserves and demand deposits are equal.

It’s deposits and bank-money are equal to its loans.

That is why Fisher identified the simplification of the banking and money systems as advantages of full-reserve banking.

joebhed,

There is history that predates the goldsmiths, whose story I was already quite familiar with, thank you. I recommend reading the following:

http://moslereconomics.com/mandatory-readings/what-is-money/

I had a look at this link you provided: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Program_for_Monetary_Reform, particularly the sections on 100% banking.

I have to ask do you read the articles here at billy blog? If so, I’m surprised you don’t ask questions or enter into discussions about some of the points made here. There’s no “blind spot” – MMT flat out says that article is wrong! The author of the article believes in the money multiplier, thinks banks lend deposits and that reserves are FRNs lying around in vaults!

The reckless expansion of bank credit could easily be controlled within the existing framework if there were political will to do so. Abolishing bank created credit to achieve a similar outcome is like chopping off your leg to cure a sprained ankle.

A philosophical question meant for everyone, not just joebhed:

What is the significance of the ratio of reserves to the “circulating medium” if the reserves themselves are fiat? I don’t see how such a relationship could have any significance at all. Warehouse receipts for gold reserves in the vault, I can see, but if both are fiat isn’t it simply an arbitrary convention?

One of the blogs mentioned yesterday that the reserve ratio just puts up the cost of banking and that Canada has the most advanced system because their reserve ratio is zero.

The significance of the ratio is that lots of people think it controls something. It’s another religious position based on causation not correlation.

“and makes loans to bankers if needed.”

If the central bank makes loans to bankers in any circumstances that involves the expansion of the balance sheet of the central bank (ie the central bank isn’t subject to the full reserve requirement as well) then you defeat the full reserve system because then bankers can cheat by making loans and getting newly creating money from the central bank.

The entire bank ecosystem must have a fixed consolidated balance sheet size for the system to work.

Jeff,

I had read Warren’s postings of the Innes “book” a while back.

It was mainly a treatise on the history of coins as money, an attack on A. Smith for the author’s currency, and an advancement of the notion – to which I do not subscribe – that money is NOT, and credit IS.

Anyway I’m not what sure what you wanted me to get out of that.

It’s a great historical read, and helped pave the way for acceptance of the Fed’s fractionally-reserved bank-credit money system.

I think it’s fair to say that the question of what money “is” remains open for discussion.

I’m more inclined to DelMar’s historical perspective on money and civilization. And on Soddy’s scientific analysis of The Role of Money and his Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt as the turning point for discussion.