I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When you’ve got friends like this … Part 4

Some time ago I started a theme “When you’ve got friends like this” which focuses on how limiting the so-called progressive policy input has become in the modern debate about deficits and public debt. Today is a continuation of that theme. The earlier blogs – When you’ve got friends like this – Part 0 – Part 1 – Part 2 and Part 3 – serve as background. The theme indicates that what goes for progressive argument these days is really a softer edged neo-liberalism. The main thing I find problematic about these “progressive agendas” is that they are based on faulty understandings of the way the monetary system operates and the opportunities that a sovereign government has to advance well-being. Progressives today seem to be falling for the myth that the financial markets are now the de facto governments of our nations and what they want they should get. It becomes a self-reinforcing perspective and will only deepen the malaise facing the world.

One of the authors I consider today is associated with the New Political Economy Network and I considered that organisation’s input into the policy debate in this blog – A new progressive agenda?. This blog could have easily been Part 4 in this series.

There was an article in the UK Guardian (March 18, 2011) – Osborne must change tack, or risk being blown off course – which sounded, on face value, that is was probably going to be on-track.

Before I read it I clicked on the links attached to the author’s names to see what their affiliation was.

One of the authors, Adam Lent is the “programme director” at the RSA which is the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. The RSA describes itself in this way:

… has been a cradle of enlightenment thinking and a force for social progress. Our approach is multi-disciplinary, politically independent and combines cutting edge research and policy development with practical action.

Okay, sounds progressive. My initial thinking about the title was probably going to be right and I could just skim the article and move on.

The other author, Tony Dolphin is a senior economist at the Institute for Public Policy Research (ippr).

The IPPR describes itself in this way:

Independent, radical, progressive

ippr has established itself as one of the most influential think tanks in British politics. Our research and policy ideas have helped shape the progressive thinking that is now the political centre ground since 1988. Our work has always been driven by a belief in the importance of fairness, democracy and sustainability. And now, at a time of economic and political crisis, we are using radical thinking to take this agenda forward.

Whoa … that is definitely progressive sounding and radical too.

Dolphin says his “areas of expertise include macroeconomic policy, the structure of the UK economy, Taxation and households’ saving and borrowing”. So he should know a thing or two about sectoral balances, monetary systems and the opportunities that being a monopoly-issuer of a currency bestows on a government such as in the UK.

I imagined that they were going to tell their readers that spending is essential for economic growth and that with private spending faltering (from a very flat position) in the UK and net exports still subtracting from growth the the austerity plans to cut spending would be devastating for the British economy.

I expected them to debunk the notion that consumers and firms are not spending in the UK at present because they are so scared of future tax increases to “pay back the deficits” that they are saving up to pay for them. This has been a central claim of the austerity proponents.

I expected them to tell their readers that the multiplied response from the public cutbacks would reduce growth (perhaps even push the UK economy back below the zero growth line) and increase unemployment. Last week’s labour force data showed unemployment to be rising again in Britain and the cuts have not even began to be felt.

I expected them to tell their readers about automatic stabilisers will probably undermine the British government’s plans to cut its deficit anyway because as economic growth falters, tax revenue will fall and welfare payments (even with the cuts) will rise automatically and push the budget into further deficit (and therefore offset the cuts in net spending).

I expected them to tell their readers about the sectoral balances – that is, debunking the myth that the government and non-government sector can simultaneously reduce their debt levels (under current arrangements).

And given that they were both associated with radical thinking (Lent is also associated with the IPPR) I wouldn’t have been surprised if they developed a narrative about how ridiculous it is that governments claim they operate at the behest of the “bond markets” which has been a central theme of the UK government as they tried to justify the unjustifiable – cut public spending in a weak economy with rising unemployment.

All those expectations ran through my mind as I began to read the article.

You can be wrong occasionally. If this article is what goes for progressive thought in the UK these days GXX help us!.

The Guardian article is a shortened version of a paper – Deficit Reduction Averaging A Plan B for fiscal tightening – put out by the IPPR this month under the author’s names.

The basic idea is that they think the British economy is still weak and vulnerable to further damage if the Government’s deficit reduction plan continues.

I agree.

They claim that the Government’s deficit reduction plan has to legitimately balance two competing sensitivities:

First, it would need to maintain market credibility by convincing those holding or purchasing gilts that the government still has a credible medium-term plan to reduce the deficit in a transparent and methodical fashion (and not by inflating it away).

Second, it would, nevertheless, need to incorporate some degree of flexibility to allow the process of deficit reduction to be slowed, or even halted, while the economy remained weak but then speeded up when output and job creation recovered.

If the word “dove” coming into mind as you read this … deficit doves.

Deficit doves think deficits are fine as long as you wind them back over the cycle (and offset them with surpluses to average out to zero) and keep the debt ratio in line with the ratio of the real interest rate to output growth. Torturous formulas are provided to students on all of this under the presumption that the government does have a financing constraint but as long as it is cautious things will be fine.

Deficit doves are within the same species as the “deficit hawks” in that they believe that the long-term deficits pose serious risks although short-term deficits might be necessary during a recession. A standard aspiration for a deficit dove is thus to propose the government runs a “balanced budget” over the business cycle which is clearly dim-witted as a stand-alone goal and un-progressive in philosophy.

From the dove viewpoint, public borrowing is constructed as a way to finance capital expenditures. Since government invests a lot in infrastructure and other public works, those investments should at least allow for a deficit. This was already recognised by the classical economists as a golden rule of public finance.

The problem that deficit doves ignore is that the budget outcome is not autonomous – that is, a deterministic balance that is controlled by the government. The budget outcome in a modern monetary economy is endogenous and determined, ultimately by the non-government saving desires. While the government can try to reduce its deficit by cutting net spending if this runs, for example, against the desires of the private domestic sector to increase their saving ratio (assuming, say a current account deficit) then the government’s aspirations will be thwarted.

The fiscal drag will combine with the spending withdrawal of the private domestic sector (and the leakage from net exports) and the economy will contract further pushing the deficit back up via the automatic stabilisers.

It is impossible for a government in a fiat monetary system to guarantee a budget deficit outcome if it is working against the behaviour of the non-government sector.

Context is everything. The reason that the deficit dove position is unsound at the national level is because they ignore the context. For example, if a government is facing an external deficit and the private domestic sector are net saving (spending less than they are earning) then to maintain economic growth the government has to be running a budget deficit.

So unless a nation can generate significant current account surpluses, then the balanced-budget over the cycle rule that deficit doves hold out will be equivalent to aiming for the private domestic sector to be dis-saving and becoming increasingly indebted over the same cycle (to the extent that the external account is in deficit).

The average extent of this private domestic sector deficit position would mirror the average current account deficit (if a budget balance was achieved). This would be tantamount to returning to the unsustainable growth path where the private domestic sector accumulates ever increasing levels of debt. That is total idiocy and reflects a lack of understanding of the way the monetary system and the aggregate relationships between the government and non-government sector work. –

In my view, deficit doves actually make the political case for full employment harder to make because they are held out as the “left wing” of the debate. So regression towards to mean takes us further to the right. Centrist positions now are out there a fair distance to the right and a long way from what we used to call the centre!

The authors want to develop a deficit reduction strategy that balances what they call “market and economic sensitivity in a simple and transparent fashion”.

The economic sensitivity is the impact of the deficit reduction on the level of activity. It will be negative – so any reduction strategy must think that a negative public contribution over the next several years is warranted. I come back to that point.

But their blind observance to the market sensitivity is what really amazed me. They say in the Guardian article that:

Osborne would counter that his most important task is to keep the markets calm by convincing them he is serious about cutting the UK’s sovereign debt. Any wavering risks higher interest rates which in itself would bring economic turmoil and hardship. He is not wrong in this but the measure of a good deficit reduction plan is its ability not simply to hold down bond traders’ blood pressure but to do so in a way that allows for a flexible response to economic uncertainty.

In their extended Report they go one step further and say it is:

… important to recognise that bond investors would be wary of any plan that lacked detail and might be more susceptible to deviation for political gain. There would, therefore, be an important role for the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which would be charged with establishing the economic outlook and determining the appropriate pace of deficit reduction in the short-term. It would also ensure that the government’s medium-term plans remain on course to achieve the ultimate target of eliminating the structural deficit by the specified date.

Aghast!

Where is the evidence that the bond markets are not calm? Answer: there is none.

Further, who cares about the bond markets. The UK government has all the power. It can simply ignore the bond markets if they get uppity. In fact a truly progressive position is to advocate the merger of the treasury and the central bank and stop issuing public debt altogher.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

But it gets worse doesn’t it? The OBR is an unelected institution made of of mainstream fiscal conservatives. What right should they have to determine “the appropriate pace of deficit reduction in the short-term”. These so-called “independent” fiscal watchdogs are a neo-liberal stunt to impose political pressure on governments to adopt conservative fiscal strategies and entrench excessive unemployment as a result.

In a democracy, the government is elected and takes the responsibility for its decisions. If we don’t like them we vote them out at the next election. We cannot vote out the OBR!

How can a progressive advocate an elected government relinquishing these important fiscal decisions and putting them into the hands of such a body as the OBR? This is neo-liberalana personified!

Lent and Dolphin typify how progressive now means right.

They say that:

To save the British economy, the chancellor should commit to an average annual reduction in the deficit, rather than set targets …

To be cute, the authors propose a Plan B – “Deficit reduction averaging”.

How does it work?

Under this plan, the government would commit to eliminating the structural deficit by a particular financial year through a mixture of spending cuts and tax increases, with the pain initially planned to be spread evenly over the life of the deficit reduction plan. Then, in each subsequent year, the required annual reduction would be recalculated, based on the actual deficit in the latest fiscal year.

In addition, should the outlook for the economy deteriorate, the government could reduce the pace of deficit reduction until economic conditions improve, at which time the pace would be speeded up in order to return the plan to target. This ensures economic sensitivity.

In effect, the Treasury would set an overall target to eliminate the deficit by a set date by achieving an average reduction in the size of the deficit each year. Because the goal for each year is an average of the remaining reduction required, rather than a pre-determined annual target (as in the current government’s plans), there is greater opportunity to change the pace and depth of consolidation in response to short-term economic fluctuations.

This approach would still require the government to establish clear spending and tax plans designed to meet each year’s fiscal target, together with an overall plan for medium-term deficit reduction. But the pace of reduction would be varied in response to different outcomes for the economy.

So that is Plan B.

What should we make of it? Answer: it is a neo-liberal ploy with softer edges and fails to address the fundamental issue – why would the British government want to eliminate the structural budget deficit?

It is taken for granted that this is an appropriate aim.

Brief refresher – what is a structural deficit?

In his New York Times article (January 6, 2011) – The Texas Omen – Krugman said that the structural budget deficit is “a deficit that persists even when the economy is doing well”.

You are led to think that when the economy is doing well there should not be a deficit. This is the standard deficit dove line that most progressive tout – thinking it sets them apart from the deficit terrorists who advocate balanced budgets or surpluses irrespective of the context.

The following blogs will give more insight into structural deficits – Structural deficits – the great con job! – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers.

The term “structural deficit” is being increasingly used in the public debate as the weak recovery ensues and the talk has turned to credible “exit” plans for fiscal policy. The mainstream economics position that budgets should be balanced or in surplus (and that the deficits being experienced at present will need to be “paid” for by offsetting surpluses then leads commentators to conclude that any estimated structural deficit is a problem.

A structural deficit is the component of the actual budget outcome that reflects the chosen (discretionary) fiscal stance of the government independent of cyclical factors.

The cyclical factors refer to the automatic stabilisers which operate in a counter-cyclical fashion. When economic growth is strong, tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this decreases during growth.

In times of economic decline, the automatic stabilisers work in the opposite direction and push the budget balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit. These automatic movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

The problem for economists is to determine whether the chosen discretionary fiscal stance is adding to demand (expansionary) or reducing demand (contractionary). It is a problem because a government could be run a contractionary policy by choice but the automatic stabilisers are so strong that the budget goes into deficit which might lead people to think the “government” is expanding the economy.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this ambiguity, economists decided to measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the budget balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

As a result, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. As I have noted in previous blogs, the change in nomenclature here is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical version of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

This framework allowed economists to decompose the actual budget balance into (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical budget balances with these unseen budget components being adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

The difference between the actual budget outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical budget outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the budget balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the budget is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual budget outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual budget outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the budget into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The question then relates to how the “potential” or benchmark level of output is to be measured. The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry among the profession raising lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. I considered that controversy in the blogs cited above.

The outcome is that the mainstream employ a biased measure of full employment (the NAIRU) to serve as the benchmark which means that any estimate of the structural deficit will always suggest that the discretionary fiscal position is “too expansionary” when in fact it is too contractionary. This reflects the bias towards higher unemployment than is necessary which is built-in to the mainstream approach.

So measurement issues aside, why should the structural deficit be zero at full employment? Answer: there is no logic to that aspiration.

It all depends on the what is going on in the economy.

it is crucial that people start to understand how the sectors that comprise the macroeconomy interact. You cannot understand statements about public sector aims – that is, whether they are appropriate or not – unless you also know what the context is.

The context is that there is no real prospect of a strong external contribution (the current account deficit widened towards the end of the year) in the UK any time soon and a highly indebted private sector suffering widespread negative equity in their housing assets. The household saving ratio has risen in recent years as they try to reduce their debt exposure. Private investment is very weak.

So under these conditions the only way that growth can continue (and expand) is that the public sector run deficits commensurate with the spending gap left by the private domestic saving and the external deficits. Given that growth has faltered in the UK and is not strong enough to prevent unemployment from rising these conditions mean that the public deficit has to expand.

Any notion of a “deficit reduction” strategy is simply irresponsible and committing the nation to rising unemployment and stagnant economic activity.

Even at full employment, if there is an external deficit and the private domestic sector desires to save overall (spend less than they earn) then the budget has to be in “structural” deficit. If from that position, the government tries to eliminate the deficit it will quickly force the economy to shed jobs and the maintenance of full employment would be impossible.

Given that the British economy is nowhere close to being at full employment and is heading away from that goal at present there is a need to widen the structural deficit.

What is clear – no progressive should entertain any notion of deficit reduction at present.

Is the deficit reduction averaging approach any different to a fiscal rule?

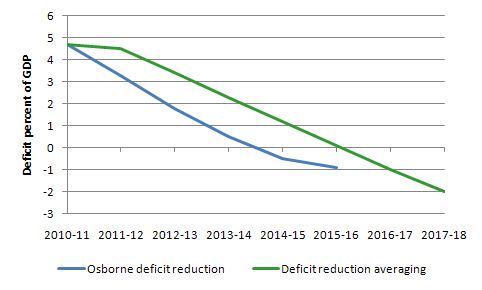

Here is a graph I created to compare the current Osborne deficit reduction plan which plans to deliver a structural deficit as a per cent of GDP of -0.9 (that is a surplus) by 2015-16 to the “progressive” deficit reduction averaging approach which plans to deliver an even larger surplus (2 per cent of GDP) two years later by 2017-18.

The latter approach takes a more gradual approach by starting less severely and then taking the difference between the end goal (which is just an imposed fiscal rule) – 2 per cent surplus – and the current budget position and dividing it by how many years are left in the deterministically-imposed adjustment path to compute how much deficit reduction occurs in each of the following years.

So it is just one fiscal rule being replaced by another. If all hell breaks loose they both fail and the automatic stabilisers will wipe them out.

You might also be wondering about why they are not only proposing to eliminate the structural deficit but actually drive it into surplus.

In the Report the authors say:

We believe that the government is right to aim for a surplus on the current budget …

Why is that an appropriate aim?

There is no further discussion which might have outlined a strong export-led strategy whereby the external sector would drive such surpluses that the private sector’s desire to net save overall would be satisfied and the government sector would have to run surpluses to take the heat out of the economy.

On all their simulated growth estimates I do not see an overheating economy envisaged.

I also don’t see any discussion about external surpluses nor a heavily debt-burdened private sector. All these realities which are intertwined with the government’s budget outcome and economic are ignored in the Report.

Is that an important oversight? Answer: definitely. Refer above to my discussion about the sectoral balances.

These characters are drawing up deficit reduction strategies without any coherent reference to the other major macroeconomic aggregates.

So if the external sector remains in deficit (and it will likely do so), their fiscal reduction plan will drive the private domestic sector into deficit (and increasing indebtedness) slightly more slowly than the Osborne plan will.

One of the major problems facing Britain at present is that indebtedness of the private domestic sector. That sector has to reduce its debt exposure. It will not be able to do that under either deficit reduction plan.

The “progressive” Report is silent on that issue which suggests to me that they haven’t even considered it. But then given at least one of them is self-proclaimed expert in “macroeconomic policy, the structure of the UK economy, Taxation and households’ saving and borrowing” it would be astonishing if they didn’t.

Which means their plan is crazy rather than just ill-informed.

Total aside – that only Australians will get

Our Prime Minister was interviewed yesterday and the press report today (March 21, 2011) that she admitted to being:

… a cultural traditionalist, indicating she will oppose moves by the Greens for euthanasia and gay marriage laws and that she believes it is important for people to understand the Bible- despite the fact she is an atheist.

I saw this photo today and wondered whether The Greens had kidnapped her and forced her undergo the “Green Treatment”.

Further, research reveals that we were not so lucky, she was visiting a laser laboratory at the ANU.

During the interview she also said that The Greens:

… did not have an economic philosophy about “reform or about growth”

That is true. Our progressive hopes are thoroughly neo-liberal when it comes to macroeconomics – that is, the big questions regarding fiscal policy.

Please read my blog – Neo-liberals invade The Greens! – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

Stay tuned for Part 5 in the series. The self-proclaimed “progressives” are trying to be relevant in the debate but really just hand over the debate to the conservatives. It is very disappointing.

That is enough for today!

Thinktanks such as the IPPR are actually a highly valuable part of the neo liberal life support system. Thay present themselves as on the left and adopt the consensus even more wholeheartedly then their so called opposition.

There is no evidence that our chancellor, or anyone else in the government, cares about the deficit.

Their outlook is basically aristocratic, and their goals are the appropriation of the public sector. I think their hatred, contempt and fear of the welfare state is the only genuine thing about them.

By crowding out genuine discourse the IPPR and their ilk do them a great service. Think of the reveal in ‘die hard 2: die harder’ when the fake soldiers are found to have been firing fake bullets at the fake terrorists.

To be fair, they might genuinely be unaware they are firing blanks, but that just means they should lay off the publications and think harder.

Their main intelectual inspiration in the paper has a rather creepily titled ‘Ten Commandments’. no X:

Commandment X: You shall coordinate your policies with other countries.

In a number of advanced countries, the reduction in budget deficits must come with a reduction in current account deficits. Put another way, if the recovery is to be maintained, the initial adverse effects of fiscal consolidation on internal demand have to be offset by stronger external demand. But this implies that the opposite happens in the rest of the world.

Good luck with that one.

Only math wonks would start counting from zero!..

But seriously, thank you, Mr Mitchell, for yet another enlightening article.

“Only math wonks would start counting from zero!”

But zero! equals 1!

I love the RSA Animates and wish someone would do one for MMT.

In the Unites States, state/local/Fed govts control ~45% (and rising) of the total annual output, up from 35% +/- since the 1970’s, 20% around 1920, and <10% at the turn of the last century- is that neoliberal austerity? What is the proper role of govt. in terms of control of the output- 60%? 80%? 100%?

Paul: There is no evidence that our chancellor, or anyone else in the government, cares about the deficit.

Their outlook is basically aristocratic, and their goals are the appropriation of the public sector. I think their hatred, contempt and fear of the welfare state is the only genuine thing about them.

Same in the good ol’ USA. Elite capture of the apparatus of the state through campaign finance, lobbying, and the revolving door ensures this. It’s all about extracting wealth from the middle and bottom, and some people are finally beginning to wake up and figure out that its class warfare, first against the poor and now against the middle class.

Yossarian, I’m not sure that government expenditure was 20% of all output during 1920. Will check up on that, but of course we haven’t had any Great Depressions where unemployment blows over 12%, or indeed, 20% for over a decade. But to answer your question, I think the “appropriate level” of output is “enough to absorb any collapse in investment output during a recession”. So probably around 30 percent.

Bill, the irony is a Christian Democrat is more likely to implement the policy recommendations flowing from MMT than a progressive liberals/Greens/ALP. After all, it was Abbott who supported the idea of a job guarantee in the last election, and in Switzerland (the world’s richest and only democracy – where they regard unemployment over 2% as an “unemployment crisis”) they (Christian Democrats) have proposed similar schemes.

Spadj: we are at ~45%- am I to assume that you would support cutting the various govt budgets by 15%?

Well, to clarify, I was focusing on the Federal government, as unlike the states, the Federal government is not finanically constrained (in the sense that states do not issue the national currency, but the Federal government does). Although I support subsidiarity so I can only think of Federal grants to administer public works locally… so whatever is necessary for it to absord the collapse in investment…

Btw, I checked up on my data, and found that Federal Government expenditure as a % of GNP back in 1929 was 2.5%; 7.2% by 1933-34. By 1970 it was 20.6%; by 1975 23.0%. I imagine it would be in the thirties today, as I initally postulated (although would need to check up on the data).

I’m surprised nobody’s defended the deficit doves yet. Though they’re wrong on some of the details, their policies are often preferable to what Bill advocates!

Long term deficits do pose a serious risk, namely that of significant currency devaluation. The effects of people losing a large part of the value of their savings are serious enough, but it also feeds into inflation.

It would only be tantamount to that if it were the household subsector accumulating ever increasing levels of debt. But the corporate subsector is a different matter entirely. Far from being unsustainable, an ever increasing debt is the sign of a healthy economy. It’s only during a downturn, when opportunities dry up, that its desire to save exceeds its desire to invest. And when that happens, it can usually be remedied by cutting interest rates.

Having seen how socialism has been unfairly discredited by the actions of those on the hard left, I can’t agree with you. I think the real reason centrist positions have drifted so far to the right is because of the lack of scrutiny that the assumptions and implications of the right get in the mainstream media.

As for structural and cyclical deficits, there is no need to complicate it with explanations that relate to capacity. The truth is far simpler – Britain was running a deficit before the credit crunch occurred. That’s a structural deficit. Now they’ve got a cyclical deficit as well.

“Long term deficits do pose a serious risk, namely that of significant currency devaluation. The effects of people losing a large part of the value of their savings are serious enough, but it also feeds into inflation.”

ya? how’s that work?

“It’s only during a downturn, when opportunities dry up, that its desire to save exceeds its desire to invest. And when that happens, it can usually be remedied by cutting interest rates.”

cite it

studentee says:

Increasing the supply of money reduces its value. In the short term this can be counteracted by increasing productivity, but in the long term it would be difficult to sustain a sufficient improvement.

It feeds into inflation because it increases the price of imports and of internationally traded commodities.

Why? Seriously, there’s so much crap about economics about that a reference would prove nothing.

But think about it – it’s built into the economic cycle! Normally recessions don’t spontaneously occur but are the product of interest rate rises. The most recent one is an exception, partly because there was a huge expanse in household debt.

“Increasing the supply of money reduces its value. In the short term this can be counteracted by increasing productivity, but in the long term it would be difficult to sustain a sufficient improvement.

It feeds into inflation because it increases the price of imports and of internationally traded commodities.”

this isn’t an argument about deficits. this is an argument about spending beyond the productive capacities of an economy. prof. mitchell always, always notes this. furthermore, capacity absolutely matters. if we target fiscal policy tightly enough, that is, at the underutilized resources, inflation pressures are minimal

“Why? Seriously, there’s so much crap about economics about that a reference would prove nothing.”

you should use evidence when making empirical assertions.

“But think about it – it’s built into the economic cycle! Normally recessions don’t spontaneously occur but are the product of interest rate rises.”

what? interest rates are an exogenous variable. you’re arguing that the recessions we’ve suffered are purposely caused by the us gov’t increasing interest rates? recessions have many causes

“The most recent one is an exception, partly because there was a huge expanse in household debt.”

so your argument about lowering interest rates as an end-all solution to when the economy is struggling fails, because it does not help in this most struggling of economies

Why? Seriously, there’s so much crap about economics about that a reference would prove nothing.

Most sensible thing I’ve read in a very long time.

i meant an empirical reference, evidence. when has a recession been averted because interest rates were lowered, i’m genuinely curious

That’s impossible to be proven, empirically or otherwise.

If recession has been averted, how would you know?

scratch averted, insert fixed. it’s a lot easier to find recessions fixed by increasing the size of the deficit

anyways, the guy said that during times when desired savings were greater than desired investment, monetary policy showed up to improve prospects. that’s something to be looked up, correct? just show me correlation, somewhere

studentee says:

This is an argument about whatever we argue about. You chose to dispute my assertion about currency devaluation.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t automatically assume Bill to be correct.

Of course capacity matters. But in the long term, tight fiscal policy is incompatible with deficits.

Maybe, but it’s not my blog – and I’m getting tired of Bill repeating the assertion about the private sector desiring to net save. There’s no evidence for it, and relying on it diminishes the quality of his arguments.

Politically, recessions have many causes. But economically it’s far simpler: they’re caused by a decline in spending. It could be declining government spending, declining exports, declining business investment or declining household spending. Interest rates affect the last two and are the primary cause of most recessions.

I didn’t say it wouldn’t help, I said it was insufficient. There’s a big difference.

As for when recessions have been fixed by lowering interest rates, the answer is nearly every recession where the government is running a consistently balanced budget (because interest rates are then the only tool they have left). USA 1920 is a particularly interesting example because it’s what the deficit hawks use to prove that moving from a deficit to a balanced budget can revive the economy. In reality a cut in interest rates was all it took to get the economy going again despite the fiscal contraction.

And most Australians recognise the (1991) Recession We Had To Have as being both the result of and the end of Paul Keating’s high interest rate policy.

“This is an argument about whatever we argue about. You chose to dispute my assertion about currency devaluation.”

you miss my point. *you* made an argument about fiscal deficits causing currency devaluation. i asked why. you said that increasing the money supply decreases the value of the dollar. i said that this is only the case if the productive capacity of the economy is unable to absorb the increased money supply via quantity, rather than price, adjustments. so your argument collapses into an argument about increasing the money supply beyond capacity, and is not about deficits, categorically

“Politically, recessions have many causes. But economically it’s far simpler: they’re caused by a decline in spending. It could be declining government spending, declining exports, declining business investment or declining household spending. Interest rates affect the last two and are the primary cause of most recessions.”

interest rates are the primary cause of most recessions, or are the latter two declining factors? i am unfamiliar with evidence that household consumption is much influenced by the prevailing interest rates. households will reduce spending when their *incomes* decline. incomes could be supplemented by taking out loans and loans are much determined by interest rates, but this approach to income augmentation is ill-advised, and the private sector’s increased leveraging was the prime factor in the instability before the most major economic collapses in us history. it is of course especially foolhardy in balance sheet recessions such as this one. continuous releveraging, this is the pattern you wish to continue?

“Of course capacity matters. But in the long term, tight fiscal policy is incompatible with deficits.”

how is it incompatible? what does the qualifier ‘tight’ connote?

“As for when recessions have been fixed by lowering interest rates, the answer is nearly every recession where the government is running a consistently balanced budget (because interest rates are then the only tool they have left).”

i’m asking just because i’m lazy here, but there haven’t been many times that a gov’t has been running a balanced budget, correct?

“Maybe, but it’s not my blog – and I’m getting tired of Bill repeating the assertion about the private sector desiring to net save. ”

Net saving is a funny concept, but it boils down to the fact that the government spending didn’t turn into taxation. If there was no ‘net-save’ bias in the economy then it would waggle up and down around zero.

So in a fiat currency with a free floating exchange rate and no foreign debt, I would say a persistent non-government surplus with no demand inflation is prima facie evidence of ‘net saving desire’. It wouldn’t exist otherwise.

studentee says:

You omitted a very important qualifier: entirely.

It is difficult for the productive capacity of the economy to entirely absorb the increased money supply via quantity rather than price adjustments.

Interest rates are the primary cause. The latter two are the mechanism.

I’m amazed that you’re unfamiliar with it. A substantial proportion of people have mortgages. When interest rates rise, they have to pay more, and they usually react by spending less. Surely you don;t think this is ill-advised?

Increased leveraging wasn’t the prime factor at all. Gross overvaluation of securitized loans was. As for continuous releveraging, I see nothing wrong with it in most cases. In the financial sector it’s a different story, which is why regulations are necessary.

The qualifier “tight connotes the government keeping it firmly under control, and that’s difficult at the best of times. But in the long term it’s much more difficult because targetting the money at underutilized resources means they cease to be underutilized.

There have been many times, though probably nowhere near as many as they tried unsuccessfully to.

MamMoTh: “If recession has been averted, how would you know?”

If you go 10 years without a recession, that is evidence that a recession has been averted. If you go 50 years without a financial panic, that is evidence that more than one financial panic has been averted. (We did that in the U.S., by the way. 🙂 )

Aidan: “I’m getting tired of Bill repeating the assertion about the private sector desiring to net save. There’s no evidence for it, and relying on it diminishes the quality of his arguments.”

There is evidence of a desire in the private sector to net save, namely, the fact that it does. Does anybody, or any institution, force people to net save? (Arguably, the payroll tax in the U.S. is forced savings, but I do not think that it is counted as private sector savings. 😉 ) The default assumption is that people who are not under duress or compulsion do what they desire to do. We can argue about that, but that takes us into psychology and philosophy.

Min says:

Claiming it to be a fact is not evidence. Do you have figures showing when it does?

Not exactly force, but central banks push people into it by raising interest rates.

“Claiming it to be a fact is not evidence. Do you have figures showing when it does?”

i think neil did a pretty good job of demonstrating this.

“You omitted a very important qualifier: entirely.

It is difficult for the productive capacity of the economy to entirely absorb the increased money supply via quantity rather than price adjustments.”

well, it depends *entirely* on how well-targeted the fiscal injections are. if the govt simply hired the unemployed, that’s targeting an obvious bad, an obvious under-utilization. if there is some inflation caused by this, so be it, i say. if you think that likely mild inflation is a greater risk than generationally entrenched poverty, so be it, you say.

“I’m amazed that you’re unfamiliar with it. A substantial proportion of people have mortgages. When interest rates rise, they have to pay more, and they usually react by spending less. Surely you don;t think this is ill-advised?”

so, there is a segment of the population with mortgages. and of this segment, a segment has loans that are floating rate. so it is a segment of a segment that would yes, be forced to pay more if interest rates are raised. but at the same time, the gov’t is issuing debt at the new rate, and at a higher rate, so larger coupon payments are going out. that is stimulative. i’d agree with you that the contractionary forces in a rate hike are larger than the expansionary ones, but it is certainly not a wash. furthermore, it needs to be noted that who are these people who are being forced to pay more when the rates are hiked? floating-rate mortgage burdened households are working class, middle class

“Increased leveraging wasn’t the prime factor at all. Gross overvaluation of securitized loans was. As for continuous releveraging, I see nothing wrong with it in most cases. In the financial sector it’s a different story, which is why regulations are necessary.”

increasing leveraging is the flip-side of those grossly overvalued securities. what were those securities made up of? how could they exist? because of the leveraging up of the private sector, particularly the working class

“There have been many times, though probably nowhere near as many as they tried unsuccessfully to.”

it is my understanding that there have not been many times

using just monetary policy to promote price stability and full employment is messy.

it has been shown to have been mostly useless in the current recessionary period

Neil Wilson says:

I’m not denying the existence of what most of us have in our pockets. But net saving is where savings increase faster than investment, and with a debt backed monetary system there is no reason why there must or should be a desire to do this.

What variable would waggle? Zero in what units?

Things happen whether or not there’s a desire for them to.

“…and with a debt backed monetary system there is no reason why there must or should be a desire to do this.”

knightian uncertainty

studentee says:

Whereas I think Neil demonstrated nothing.

…until the government runs out of unemployed to target.

The issue we were discussing is whether it causes currency devaluation, not whether it’s worth doing.

And that segment of a segment is over a quarter of the total population.

The expansionary forces in a rate hike are insignificant. For those who have money in the bank or the bond market, they have a greater incentive to keep it there. For those who owe the bank money, it makes sense to pay off as much as they can so they won’t end up owing more.

So you agree it’s better to keep interest rates low?

I was referring to leveraging up of businesses, not households. The latter can be a problem, but I think land taxes are the best solution. But even there, my point stands: banks would not have made those loans if others hadn’t been willing to buy up securitized debt for far more than it was actually worth.

I don’t dispute that. My point is that it can be an effective course of action, not that it’s the best one.

I’ve already said it’s insufficient this time.

“…until the government runs out of unemployed to target.”

yup

“The issue we were discussing is whether it causes currency devaluation, not whether it’s worth doing.”

hiring individuals who are not bid on at the minimum fixed wage is not inflationary

“And that segment of a segment is over a quarter of the total population.”

i’d like to see a cite on this one. not because i don’t believe you, i’m just curious where to find information like this.

“The expansionary forces in a rate hike are insignificant. For those who have money in the bank or the bond market, they have a greater incentive to keep it there. For those who owe the bank money, it makes sense to pay off as much as they can so they won’t end up owing more.”

you can claim this, i guess, but it’s clearly not a wash. and again this only applies to those whose rates are adjustable. and again those most punished are those who will and can’t just start paying off quickly

“So you agree it’s better to keep interest rates low?”

i believe the position taken by many mmt’ers is that the rates should be kept near zero

“I was referring to leveraging up of businesses, not households. The latter can be a problem, but I think land taxes are the best solution. But even there, my point stands: banks would not have made those loans if others hadn’t been willing to buy up securitized debt for far more than it was actually worth.”

yeah, see, that’s why i called it the flip-side. the two coexist. and that’s what monetary policy is much about, releveraging. only capital injections through fiscal policy can actual improve wrecked balance sheets

studentee says:

It’s something I found out watching TV. But there are plenty of online reports backing it, such as

http://www.rpdata.com/property_news/proportion_of_homes_with_mortgage_on_the_rise.html and

http://www.infochoice.com.au/home-loans/news/fixed-rate-loans-gaining-popularity/38888/2/1,22,24,3,37

The phrase “not a wash” is not used here, so I’m not sure whether you’re agreeing with me or not.

And that’s a sensible position… but once the economy is going well then inflation will need to be high unless the government runs surpluses.

How do you mean?

“with a debt backed monetary system there is no reason why there must or should be a desire to do this.”

It depends what you mean by desire. In aggregate there is a constant accumulation of the nominal unit. If that isn’t an expression of choice to hold the unit of currency then you need to come up with a different explanation of what it is and why it comes about automatically.

“What variable would waggle? Zero in what units?”

The government deficit would waggle up and down around zero in the nominal unit of currency with savings and investment perfectly balanced over time.

“Things happen whether or not there’s a desire for them to.”

Again it depends upon what you interpret from the term ‘desire’. However the facts are clear. Currency users accumulate the nominal unit over time. There has to be a reason why they do that.

“Not exactly force, but central banks push people into it by raising interest rates.”

So is that the same as saying that the central bank’s policy influences people’s desires?

Neil Wilson says:

No. I’m saying that the central bank’s policy influences people’s behaviour, which is a different thing entirely.

What evidence do you have that there’s a constant accumulation of cash? Are you sure you’re not confusing net saving with saving?

I disagree, as there would still be scope for prolonged external imbalances.

“No. I’m saying that the central bank’s policy influences people’s behaviour, which is a different thing entirely.”

It seems to me that you have taken your definition of the word ‘desire’ and interpreted the language from your perspective.

I would say influence behaviour is precisely the definition of ‘aggregate desire’.

“What evidence do you have that there’s a constant accumulation of cash?”

There is a constant accumulation of the nominal unit – that is what the national debt is. It’s not denominated in rabbits.

“I disagree, as there would still be scope for prolonged external imbalances”

Two centuries of accumulation is a bit long to suggest that it is an imbalance.

Moi: “There is evidence of a desire in the private sector to net save, namely, the fact that it does.”

Aidan: “Claiming it to be a fact is not evidence. Do you have figures showing when it does?”

This is not an empirical question, but a definitional one.