I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

A new progressive agenda?

Today I am heading into the lands of austerity – those scorched, barren places where people with increasingly hollowed out faces are being forced by their misguided polities to forego wages and conditions and pensions and their happiness because some neo-liberal told them that government deficits were bad and all that. I am off to London this afternoon (I am typing this on the train to Sydney) and then to Maastricht University where visit each year and my colleague Joan Muysken is located. I have been thinking about various efforts that have emerged in the recent period suggesting that a new progressive agenda (narrative) is required to reverse the onslaught of neo-liberalism. This is clearly a topic close to my own heart. I have been thinking about the development of an alternative economic paradigm for my whole academic career. So whenever I see some progressive efforts I am always interested. This blog considers that question. So now a long flight then I will report on how hollow those faces are becoming.

At the outset, I note that the IMF are “demanding” a further incursion into the democratic rights of citizens with their proposal to require – financial stability tests for the top financial centres (nations).

Up until now, the IMF has been running what they call the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) which countries voluntarily acceded to. This assessment examines – from the biased (neo-liberal) perspective of the IMF – the “soundness of the banking and other financial sectors” and the regulative structures in place. It is interesting that the IMF who now considers it qualified to judge these things promoted policy frameworks and lauded private sector behaviour that created the crisis in the first place.

The IMF paradigm is a central part of why we are in crisis. It is also part of the reason why the resolution to the recession is taking so long and the reason why many nations are facing the prospects of a double-dip in the coming months.

But now they think they are to be the major judges of sensible financial regulation and bank behaviour.

In that regard, the Washington bullies are now claiming that submission to their processes are mandatory for the countries that comprise “the world’s top 25 financial sectors”.

They claim that:

This decision is a concrete step toward strengthening the IMF’s surveillance of those members whose financial sectors could have the biggest potential impact on global stability.

You can see the list of 25 nations (which includes Australia) at the IMF home page.

So Julia (Australia’s new Prime Minister), send the IMF a quick E-mail and tell them to take a long walk (off a short pier). Along with the supposed “independent” central banks and the rising swell to impose tight fiscal rules on government treasury operations, this type of policy development represents a further erosion of our rights to determine what the government does and how.

The neo-liberal IMF paradigm want the big companies (on Wall Street etc) and unelected officials (in Washington and on central bank boards) to determine economic policies and they want to bolt down our elected officials (who determine fiscal policy stances) as much as possible.

For some reason as I was reading the IMF Press Release this morning, I started to recite the 1971 poem/song – The Revolution Will Not Be Televised – by Gil Scott-Heron. Here is the mantra:

The revolution will not be televised, will not be televised,

will not be televised, will not be televised.

The revolution will be no re-run brothers;

The revolution will be live.

Ultimately these degradations of our democratic rights will have social and political consequences. The impact of the Washington consensus has been to increase inequality within and between our nations. Then overlay that with the crisis that the blind doctrine of market self-regulation brought which has impoverished millions and put back economic growth for years. The upshot will be social instability in many nations.

That may be the way we jettison the dominance of the econocrats from Washington and elsewhere (Frankfurt, Brussel etc).

While on the topic of revolutions, my favourite song on this theme comes from the fabulous band (one of my favourites) – the Brooklyn Funk Essentials who told us that Revolution was Postponed because of Rain. It is a very stark commentary on the so-called progressive side of the political struggle. For your enjoyment, I have posted the lyrics to the song at the end of this blog. The music is equally exceptional – here at You Tube.

Which brings me to my main topic today.

Last week, in this blog – Heading back to where we started – I noted that the New Political Economy Network in Britain has been established to develop alternative economic policy as a way out of the IMF-type straitjacket.

The Network published a new e-book which outlines “ideas for what a new political economy for Labour should look like”. Labour being the British Labour Party that lost its way badly when it conjured up its Third Way nonsense and proceeded to act in a thoroughly neo-liberal manner with the result being that they messed up but in doing so has pushed Britain further to the right than one could imagine.

So it is apposite that groups of informed citizens form networks to prosecute revolutionary overalls of their political institutions. Revolution being in my mind today!

There was an article which appeared in the UK Guardian on September 21, 2010 – Britain’s economy is broken. This is how to start fixing it – which provided a brief glimpse into the manifesto that the New Political Economy Network is proposing.

In general, the problems with the policy structures and visions that the major political parties now squabble over are not confined to Britain. Just look at the dysfunctional mess that is US politics. Further, the recent Australian federal election demonstrated the poverty of policy development here.

In that campaign, we saw the two major parties which used to represent left and right, respectively, now fighting about the “centre” which has moved significantly towards what used to be called right-wing.

The major economic stance being articulated in this struggle was who would deliver the biggest budget surplus in the shortest period of time – at a time when we have official labour underutilisation rates of around 13 per cent.

So the New Political Economy Network is really reflecting a global problem – Capitalism is broken. This is how to start fixing it.

I also agree with them that the financial crisis which morphed quickly into a real economic crisis should have marked the end of the dominance of neo-liberalism in the policy sphere. There should have been new insights into the relative importance of fiscal policy viz-a-viz monetary policy. Organisations such as the OECD and the IMF should have been disbanded and their official retrained to fight cancer or otherwise perform useful tasks. The Eurozone should have collapsed. Most of the economics departments should have closed down and new political economy departments formed.

All this is dreaming I know. The reality is that the dominance of mainstream economists has been shaken but not destroyed. The left-wing appears to be unable to mount any coherent attack on the dominant neo-liberal paradigm – often because it is so divided within itself. Arcane internecine disagreements have always undermined the solidarity of the progressive side of politics.

I think the progressive response in the current crisis has also been fairly weak. Please read my blogs – The enemies from within and When you’ve got friends like this … Part 1 and When you’ve got friends like this … Part 2 and The progressives have failed to seize the moment – for more discussion on this point.

The New Political Economy Network notes that the British Labour Party:

… hasn’t debated what that alternative should be – not just during this summer’s leadership campaign but for the best part of two decades. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that since 1994, the party’s mainstream outsourced its economic thinking to Gordon Brown, who in turn took his cues from straightlaced economists and the City. The result was neoliberalism-lite, and some of the most unsightly political contortions ever pulled by a prime minister.

As I noted in my blog the other day, I have a lot of sympathy for this view. In my view, the progressive side of the debate will only be advanced when central macroeconomic myths about the way the monetary system operates and the impacts of budget deficits etc are challenged head -on.

Too often the so-called progressives engage in “cute” political discourse along the lines that they will balance the budget across the economic cycle without knowing what that actually implies for the outcomes in the private domestic sector (for example). They buy into the surplus-obsession saying they will “run surpluses but be fairer about it”.

This has been a central criticism I have made of the most progressive political party in Australia – The Greens. They advocate economic policies that largely undermine the capacity to pursue their enlightened social and environmental policies. Please read my blogs on this topic – Neo-liberals invade The Greens! – A response to (green) critics … Part 1 – A response to (green) critics … Part 2 and A response to (green) critics – finale (for now)! – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that by accepting this mantra they fail to fundamentally challenge the mainstream macroeconomics myths. Leadership is about pushing the boundaries of the political debate rather than being constrained by the existing orthodoxy – which in this case has categorically failed to achieve what they held out – stable growth, increased living standards and more incentives for people to advance their own lives.

I note that there has been some attention in the press given to the e-book manifesto from the New Political Economy Network in recent days. I also note that has put out a new book by Will Hutton – Them and Us: Politics, Greed and Inequality – Why We Need a Fair Society – which also purports to outline a new path for the progressives in Britain (but presumably everywhere).

Both books were reviewed in the UK Guardian over the last few days. The UK Guardian also carried a review of Will Hutton’s latest book by Robert Skidelsky (September 25, 2010) – Them and Us: Politics, Greed and Inequality – Why We Need a Fair Society by Will Hutton.

Skidelsky, who was Keynes biographer said that Hutton’ book is another “passionate and erudite proposal to fix Britain’s broken economy”. I haven’t read this book so I will leave my judgement of it for another day.

The e-book traverses a similar theme to that developed in my blog last year – The origins of the economic crisis. It notes that wage share in the UK has fallen dramatically over the last three decades and that:

The rising wealth and income gap has been a relentless trend that three Labour administrations have failed to reverse.

The manifestation of this rising inequality is to be found in the fact that “(w)ages for most of the population have been falling behind the growth in productivity, and at an accelerating rate”. This is not a trend that is confined to the UK. This has been the hallmark of the neo-liberal period and is a significant causal factor in relation to the financial crisis.

The declining wage share has meant that more real output (income) has been able to be expropriated by capital and these expanding surpluses, accumulated at the expense of the workers who created the product, became the gambling chips for the rapidly expanding financial sector.

We were all fed the story that this was the path to wealth for all of us. For a while, nominal wealth did grow although its distribution did not become fairer. But the financial crash wiped out significant portions of accumulated wealth that workers had accumulated. The top-end-of-town however has been less damaged.

Further, as the wage share has declined the distribution of wages has become more unequal with an:

… increasing concentration of earnings at the top … real earnings have risen much faster for high-earners than for median- and low-earners. As a result, the brunt of the falling wage share has been borne almost entirely by middle- and lower paid employees, with the bottom two-thirds of earners facing a shrinking share of a diminishing pool.

Again, this is a trend among most advanced nations. In part, it has been due to the growth of the FIRE sector.

The e-book from the New Political Economy Network argues that three “key elements of market fundamentalism have caused this problem”.

- The abandonment of the post-war commitment to full employment.

- A succession of measures aimed at weakening unions, axing employee rights and eroding the role of collective bargaining.

- The adoption of a new business model of shareholder value was aimed at maximising short-term share prices and profits, through a wave of financial engineering and cost-cutting.

I totally agree with this assessment.

In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned we cover these themes in detail.

We outlined what we called the full employment framework and its traced its demise under neo-liberalism and its ultimate replacement with the diminished full employability framework. We noted that under the former framework, everybody who wanted to earn an income was able to find employment. Maintaining full employment was an overriding goal of economic policy which governments of all political persuasions took seriously.

In Australia, for example, unemployment rates below two per cent were considered normal and when unemployment threatened to increase, government intervened by stimulating aggregate demand. Even conservative governments acted in this way, if only because they feared the electoral backlash that was associated with unemployment in excess of 2 per cent.

While unemployment was seen as a waste of resources and a loss of national income which together restrained the growth of living standards, it was also constructed in terms of social and philosophical objectives pertaining to dignity, well-being and the quest for sophistication. It was also clearly understood that the maintenance of full employment was the collective responsibility of society, expressed through the macroeconomic policy settings. Governments had to ensure that there were jobs available that were accessible to the most disadvantaged workers in the economy. We called this collective enterprise the Full Employment framework

.

This framework has been systematically abandoned in most OECD countries over the last 30 years. The overriding priority of macroeconomic policy has shifted towards keeping inflation low and suppressing the stabilisation functions of fiscal policy. Concerted political campaigns by neo-liberal governments aided and abetted by a capitalist class intent on regaining total control of workplaces, have hectored communities into accepting that mass unemployment and rising underemployment is no longer the responsibility of government.

As a consequence, the insights gained from the writings of Keynes, Marx and Kalecki into how deficient demand in macroeconomic systems constrains employment opportunities and forces some individuals into involuntary unemployment have been discarded. The concept of systemic failure has been replaced by sheeting the responsibility for economic outcomes onto the individual.

Accordingly, anyone who is unemployed has chosen to be in that state either because they didn’t invest in appropriate skills; haven’t searched for available opportunities with sufficient effort or rigour; or have become either “work shy” or too selective in the jobs they would accept.

Governments are seen to have bolstered this individual lethargy through providing excessively generous income support payments and restrictive hiring and firing regulations. The prevailing view held by economists and policy makers is that individuals should be willing to adapt to changing circumstances and individuals should not be prevented in doing so by outdated regulations and institutions. The role of government is then prescribed as one of ensuring individuals reach states where they are employable.

This involves reducing the ease of access to income support payments via pernicious work tests and compliance programs; reducing or eliminating other “barriers” to employment (for example, unfair dismissal regulations); and forcing unemployed individuals into a relentless succession of training programs designed to address deficiencies in skills and character. We called this new paradigm the Full Employability framework.

The framework is exemplified in the 1994 Jobs Study published by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Its main message (OECD, 1994, vii) accurately summarises the current state-of-the-art in policy thinking

… it is an inability of OECD economies and societies to adapt rapidly and innovatively to a world of rapid structural change that is the principal cause of high and persistent unemployment … Consequently, the main thrust of the study was directed towards identifying the institutions, rules and regulations, and practices and policies which have weakened the capacity of OECD countries to adapt and to innovate, and to search for appropriate policy responses in all these areas … Action is required in all areas simultaneously for several reasons. First, the roots of structural unemployment have penetrated many if not all areas of the socioeconomic fabric; second, the political difficulties of implementing several of these policies call for a comprehensive strategy … third, there are synergies to exploit if various microeconomic polices are pursued in a co-ordinated way, both with regard to each other and the macroeconomic policy stance.

The OECD Jobs Study (1994: 74) also ratified the growing macroeconomic conservatism by articulating that the major task for macroeconomic policy was to allow governments to ‘work towards creating a healthy, stable and predictable environment allowing sustained growth of investment, output and employment. This implies a reduction in structural budget deficits and public sector debt over the medium term … [together with] … low inflation.’

Prior to the financial crisis, the OECD consistently claimed that its policy recommendations were delivering successes in countries that have implemented them. Unfortunately, the reality is strikingly at odds with this political hubris. Even with more than a decade of fairly stable economic growth in most nations leading up to the crisis, most countries still languished in high states of labour underutilisation and low to moderate economic growth.

Further, underemployment is becoming an increasingly significant source of wastage. Youth unemployment remains high. Income inequalities are increasing. The only achievement is that inflation is now under control, although it was the severity of the 1991 recession that expunged inflationary expectations from the OECD block. Since that time, labour costs have been kept down by harsh industrial relations deregulation and a concerted attack on the labour unions.

The policy approach used to banish one of the twin evils – inflation – has left the evils of unemployment and underemployment in its wake. The result is that after 30 years of public expenditure cutbacks and, more recently, increasing government bullying of the jobless, OECD economies generally did not get close to achieving full employment. These pathologies have magnified as a result of the recent crisis and the policy frameworks established under the aegis of the OECD Jobs Study have only made workers more vulnerable than they otherwise would have been.

In the midst of the on-going debates about labour market deregulation, scrapping minimum wages, and the necessity of reforms to the taxation and welfare systems, the most salient, empirically robust fact of the last three or more decades – that actual GDP growth has rarely reached the rate required to maintain, let alone achieve, full employment – has been ignored.

An understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) allows one to lay most of the blame for this labour underutilisation across OECD countries lies with the policy failures of national governments. At a time when budget deficits should have been used to stimulate the demand needed to generate jobs for all those wanting work, various restrictions have been placed on fiscal policy by governments influenced by orthodox macroeconomic theory.

Monetary policy has also become restrictive, with inflation targeting – either directly or indirectly – pursued by increasingly independent and vigilant central banks. These misguided fiscal and monetary stances have damaged the capacities of the various economies to produce enough jobs.

The attacks on the welfare system have, in part, been driven by the overall distaste among the orthodox economists for the activist fiscal policy essential to the maintenance of full employment. Counter-cyclical fiscal policy is now eschewed and monetary policy has become exclusively focused on inflation control. There are many arguments (fears) used to justify this position, including the (alleged) dangers of inflation and the need to avoid crowding out in financial markets.

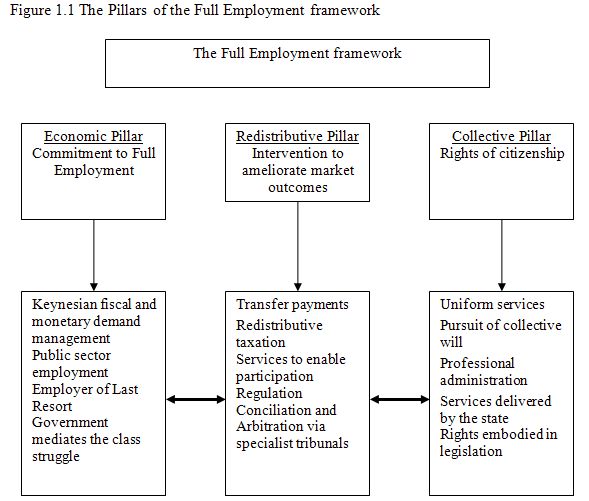

The following graph sketched our depiction of the full employment framework and is taken from the our book – Full Employment abandoned.

The three pillars defined the Post World War 2 economic and social settlement in most Western countries First, the Economic Pillar was defined by an unambiguous commitment to full employment, which became increasingly blurred as the NAIRU dogma emerged in the late 1960s. Second, the Redistributive Pillar was designed to ameliorate market outcomes and defined much of the equity intervention by government. It recognised that the free market was amoral and intervention in the form of income support and wage setting norms was a necessary part of a sophisticated society. Third, the Collective Pillar provided the philosophical underpinning for the Full Employment framework and was based on the intrinsic rights of citizenship.

This depiction is a stylisation and that there were many individual nuances in particular countries over the period considered.

The Great Depression taught us that, without government intervention, capitalist economies are prone to lengthy periods of unemployment. The emphasis of macroeconomic policy in the period immediately following the Second World War was to promote full employment. Inflation control was not considered a major issue even though it was one of the stated policy targets of most governments.

In this period, the memories of the Great Depression still exerted an influence on the constituencies that elected the politicians. The experience of the Second World War showed governments that full employment could be maintained with appropriate use of budget deficits. The employment growth following the Great Depression was in direct response to the spending needs that accompanied the onset of the War rather than the failed Neoclassical remedies that had been tried during the 1930s. The problem that had to be addressed by governments at War’s end was to find a way to translate the fully employed War economy with extensive civil controls and loss of liberty into a fully employed peacetime model.

As a consequence, in the period between 1945 through to the mid 1970s, most advanced Western nations maintained very low levels of unemployment, typically below 2 per cent. Figure 1.2 shows that the performance of the labour market during the Keynesian full employment period was in stark contrast to what followed and what had preceded it.

However, while both private and public employment growth was relatively strong during the Post War period up until the mid 1970s, the major reason that the economy was able to sustain full employment was that it maintained a buffer of jobs that were always available, and which provided easy employment access to the least skilled workers in the labour force. Some of these jobs, such as process work in factories, were available in the private sector.

However, the public sector also offered many buffer jobs that sustained workers with a range of skills through hard times. In some cases, these jobs provided permanent work for the low skilled and otherwise disadvantaged workers.

Importantly, the economies that avoided the plunge into high unemployment in the 1970s maintained what Paul Ormerod described in his book The Death of Economics (1994: 203) as a:

…sector of the economy which effectively functions as an employer of last resort, which absorbs the shocks which occur from time to time, and more generally makes employment available to the less skilled, the less qualified.

Ormerod said that employment of this type may not satisfy narrow Neoclassical efficiency benchmarks, but notes that societies with a high degree of social cohesion and a high valuation on collective will have been willing to broaden their concept of costs and benefits of resource usage to ensure everyone has access to paid employment opportunities.

Ormerod (1994: 203) argued that countries like Japan, Austria, Norway, and Switzerland were able to maintain this capacity because each exhibited:

…a high degree of shared social values, of what may be termed social cohesion, a characteristic of almost all societies in which unemployment has remained low for long periods of time.

The full employment commitment (the Economic Pillar) was buttressed by the development of the Welfare State, which defined the state’s obligation to provide security to all citizens. Citizenship embraced the notion that society had a collective responsibility for the well-being of its citizens and replaced the dichotomy that had been constructed between the deserving and undeserving poor.

The Redistributive Pillar recognised that the mixed economy (with a large market-component) would deliver poor outcomes to some citizen, principally via unemployment. Extensive transfer payments programs were designed to provide income support to disadvantaged individuals and groups. Underpinning the Welfare State and the economic commitment to full employment was a sophisticated concept of citizenship (the Collective Pillar).

The rights of citizenship meant that individuals had access to the distribution system (via transfer payments) independent of market outcomes. Furthermore, a professional public sector provided standardised services at an equivalent level to all citizens as a right of citizenship. These included the public sector employment services, public health and education systems, legal aid and a range of other services.

The stability of this Post-War framework with the Government maintaining continuous full employment via policy interventions was always a source of dissatisfaction for the capitalist class. This was particularly the case in the late 1960s as national debates arose about trade union power. Taking Australia as an example, there is compelling evidence to show that the captains of industry were pressuring government to create some labour slack in the economy and that the entreaties were received sympathetically by key conservative politicians. However, the chance to break the Post-War stability came in the mid-1970s.

Following the first OPEC oil price hike in 1974, which led to accelerating inflation in most countries, there was a resurgence of pre-Keynesian thinking. Inflationary impulses associated with the Vietnam War had earlier provided neo-liberal economists with opportunities to attack activist macroeconomic policy in the United States.

Governments around the world reacted with contractionary policies to quell inflation and unemployment rose giving birth to the era of stagflation. The economic dislocation that followed provoked a paradigm shift in macroeconomics. The Keynesian notion of full employment, defined by Nobel Prize winner William Vickrey (1993) as ‘a situation where there are at least as many job openings as there are persons seeking employment’ was abandoned as policy makers progressively adopted Milton Friedman’s conception of the natural rate of unemployment.

This has more recently been termed the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) approach. This approach redefines full employment in terms of a unique unemployment rate (the NAIRU) where inflation is stable, and which is determined by supply forces and is invariant to Keynesian demand-side policies.

It reintroduces the discredited Say’s Law by alleging that free markets guarantee full employment and Keynesian attempts to drive unemployment below the NAIRU will ultimately be self-defeating and inflationary. The Keynesian notion that unemployment represents a macroeconomic failure that can be addressed by expansionary fiscal and/or monetary policy is rejected.

Instead, unemployment reflects failures on the supply side failures such as individual disincentive effects arising from welfare provision, skill mismatches, and excessive government regulations (OECD, 1994). Extreme versions of the natural rate hypothesis consider unemployment to be voluntary and the outcome of optimising choices by individuals between work (bad) and leisure (good).

As, what is now referred to as, neo-liberalism took hold in the policy making domains of government, advocacy for the use of discretionary fiscal and monetary policy to stabilise the economy diminished, and then vanished. In the mid-1970s the opposition to the use of budget deficits to maintain full employment became visible for the first time and the inflation-first rhetoric emerged as the dominant discourse in macroeconomic policy debates.

The rhetoric was not new and had previously driven the failed policy initiatives during the Great Depression. However, history is conveniently forgotten and Friedman’s natural rate hypothesis seemed to provide economists with an explanation for high inflation and alleged three main and highly visible culprits – the use of government deficits to stimulate the economy; the widespread income support mechanisms operating under the guise of the Welfare State; and the excessive power of the trade unions which had supposedly been nurtured by the years of full employment.

All were considered to be linked and anathema to the conditions that would deliver optimal outcomes as prescribed in the Neoclassical economic (textbook) model. With support from business and an uncritical media, the paradigm shift in the academy permeated the policy circles and as a consequence governments relinquished the first major pillar of the Post-War framework – the commitment to full employment. It was during this era that unemployment accelerated and has never returned to the low levels that were the hallmark of the Keynesian period.

The NAIRU approach extolled, as a matter of religious faith, that government could only achieve better outcomes (higher productivity, lower unemployment) through microeconomic reforms. In accordance with the so-called supply-side economics, governments began to redefine the Economic Pillar in terms of creating a greater reliance on market-based economic outcomes with a diminished public sector involvement.

In many countries successive governments began cutting expenditures on public sector employment and social programs; culled the public capacity to offer apprenticeships and training programs, and set about dismantling what they claimed to be supply impediments (such as labour regulations, minimum wages, social security payments and the like).

Within this logic, governments adopted the goal of full employability, significantly diminishing their responsibility for the optimum use of the nation’s labour resources. Accordingly, the aim of labour market policy was limited to ensuring that individuals are employable. This new ambition became exemplified in the 1994 OECD Jobs Study.

As a result, successive governments in many countries began the relentless imposition of active labour market programs. These were designed to churn the unemployed through training programs and/or force participation in workfare compliance programs. The absurdity of requiring people to relentlessly search for work, and to engage in on-going training divorced of a paid-work context, seemed lost on government and their policy advisors. That the NAIRU approach seduced them at all is more difficult to understand given stark evidence that since 1975 there have never been enough jobs available to match the willing labour supply.

The OECD Jobs Study (1994) set the tone for this neo-liberal labour market agenda. This agenda makes the goal of full employability pre-eminent and disregards policies that might increase the rate of overall job creation.

A fully employed economy provides life-long training and learning opportunities in the context of paid employment. Firms become responsible for adjusting hiring standards and on-the-job training programs to match the available talents of the labour force. Under the flawed doctrine of full employability, labour market programs mainly function to subsidise the needs of private capital. Further, unemployment has become a business.

Many market-based organisations have benefited from this new approach to delivering labour market services. Small entrepreneurs, community activists, and private welfare agencies have become the agencies that administer these neo-liberal labour market policies.

The shift to an emphasis on full employability was accompanied by substantial changes in the conduct of macroeconomic policy. In Chapter 6 we consider inflation targeting, which was one strand of the macroeconomic accompaniment to the supply side microeconomic policy agenda set out in the 1994 Jobs Study.

Not only have the neo-liberals rejected the notion that demand deficiencies can occur. They have also been successful in making inflation appear to be a worse bogey person than unemployment. It is clear that the political importance of inflation has been blown out of all proportion to its economic significance. After dismissing the arguments that inflation imposes high costs on the economy, Alan Blinder wrote in 1987 (page 33) that:

The political revival of free-market ideology in the 1980s is, I presume, based on the market’s remarkable ability to root out inefficiency. But not all inefficiencies are created equal. In particular, high unemployment represents a waste of resources so colossal that no one truly interested in efficiency can be complacent about it. It is both ironic and tragic that, in searching out ways to improve economic efficiency, we seem to have ignored the biggest inefficiency of them all.

The abandonment of full employment presented neo-liberal governments with a new problem. With unemployment persisting at high levels due to the deliberate constraints imposed on the economy by restrictive fiscal (and monetary) policy, rising welfare payments placed pressures on the Redistributive Pillar. These pressures were erroneously seen as a threat to the fiscal position of government.

It is clear from the perspective of MMT that national governments (non EMU) are never financially constrained and so the neo-liberal justification for cutting welfare to ‘save money’ is flawed at the most elemental level.

However, the neo-liberals managed to convince policy makers that fiscal conservatism was necessary and that the only way to resolve the pressures on the Redistributive Pillar was to reduce the public commitment to income support and the pursuit of equity. Accompanying the neo-liberal attacks on macroeconomic policy were concerted attacks on the supplementary institutions such as the industrial relations system and the Welfare State. For these attacks to be effective required a major recasting of the concept of citizenship.

Governments, aided by the urgings of the neo-liberal intellectuals in the media and in conservative think tanks, thus set about redefining the Collective Pillar, which had been an essential part of the rationale for the system of social security.

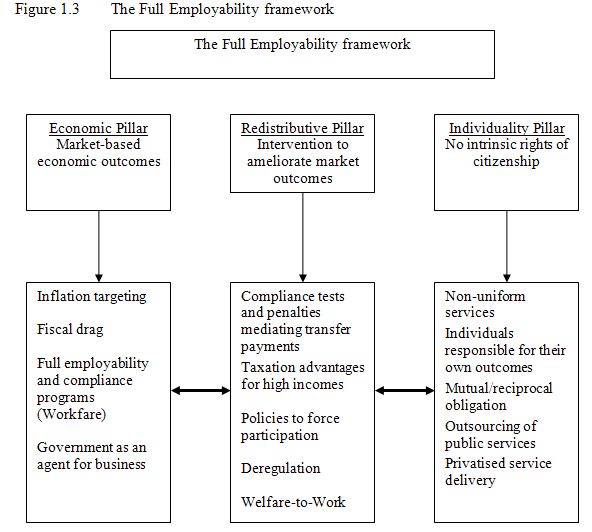

The next chart shows our conception of the Full Employability framework. Under this framework, collective will has been usurped by the primacy of the individual. The hallmark of the neo-liberal era is that individuals have to accept responsibility, be self-reliant, and fulfill their obligations to society.

Unemployment is couched as a problem of welfare dependence rather than a deficiency of jobs. To break this welfare dependency required responsibility to be shifted from government to the individual. To force individuals to become accountable for their own outcomes, governments embraced a shift from active to passive welfare and the introduction of alleged responsibilities to counter-balance existing rights.

This is sometimes referred to as reciprocal obligation. Individuals now face broader obligations and, in many countries, their rights as citizens have been replaced by compulsory contractual relationships under which receipt of benefits is contingent on meeting behavioural criteria. Reciprocal obligation was developed as a leading principle in several countries as a means of reintegrating the allegedly, welfare dependent underclass into the community.

Unfortunately, there is no reciprocal obligation on government to ensure that there are enough jobs for all those wanting work. The major shortcoming of the Full Employability framework is that the focus on the individual ignores the role that macroeconomic constraints play in creating welfare dependence. It is a compositional fallacy to consider that the difference between getting a job and being unemployed is a matter of individual endeavour or preference. Adopting welfare dependency as a lifestyle is different to an individual, who is powerless in the face of macroeconomic failure, seeking income support as a right of citizenry.

I read the e-book from the New Political Economy Network within the context of my thinking about full employment and full employability. If you decompose the policies that accompanied each framework it is not hard to see why the distribution of national income moved dramatically in favour of capital.

It is not hard to understand the rising dominance of the financial sector and the proliferation of financial products that ultimately were time bombs. It is clear that the fault lies with government – its failure to regulate – its failure to provide enough jobs, thinking that a self-regulating private market would step in where the public sector used to play a crucial role as a buffer stock employer.

The New Political Economy Network notes in relation to the UK that:

In government Labour bowed to the interests of the City. It failed to protect the security of its citizens because it did not regulate the dangerous activity of the financial markets. It allowed the housing bubble to grow and personal debt to balloon – as a means of covering up for the huge gulf that was growing between the small wealthy elite and the rest.

In other words, governments allowed the destructive inner logic of capitalism to roam wider than in the past. They stopped playing a role as an intermediary between labour and capital – a role which ensured the spoils were more evenly shared and that no-one went without a paid job. Instead, they became the support team for the financial sector and introduced policies that allowed that sector to capture increasing proportions of real income.

I consider the New Political Economy Network narrative about the “development of market fundamentalism” and “the growing power of finance” – all with the assistance of our elected representatives to be interesting and compelling. It represents a good reference analysis for how we lost oversight of our representatives and didn’t notice they were no longer serving our interests but the interests of capital – more or less exclusively.

I also liked the discussion about the way we were bribed (“a new kind of consumer compact between the individual and the market began to replace the old social welfare contract”) into accepting this new policy framework. There was significant divide and rule strategies employed by governments as agents of capital to ensure that the “middle class” didn’t ask too many questions. Blaming the unemployed as the lazy detritus of this new entrepreneurial age was aided by doling out credit which allowed the rest of us to indulge in a consumption binge. The victims of all this – the most disadvantaged were easily vilified.

So there is a lot to recommend in the e-book by the New Political Economy Network.

But there is also a lot to worry about if this is purporting to be a manifesto to unite to the left and restore a progressive politics.

Rachel Reeves writing in the Guardian (September 24, 2010) says that the e-book from the New Political Economy Network should be – Essential reading for Labour’s next leader – because whichever person takes over the leadership of the Opposition they “must find a positive alternative to ideologically motivated cuts” that the Tories are implementing.

She believes that “(t)here is no bigger challenge for the next Labour leader than to build an economic policy to counter the coalition’s austerity package” – there must be a “platform that is at once both economically coherent and politically popular”. In this context, the e-book from the New Political Economy Network “offers the analysis and vision that could provide the building blocks of that strategy”.

Reeves is mostly positive but then says of the e-book:

That is not to say it has all the answers – the authors do not address how, in the medium term, they would reduce the budget deficit, which Labour must answer if we are serious about governing again.

The fundamental question that any progressive agenda has to come to terms with is the role of net public spending in the income-generating (growth) process. When I talk about growth I am always assuming we should be aiming for full employment and ecological sustainability. Growth per se is not the goal.

The New Political Economy Network say that:

In the immediate future, Labour needs to develop an alternative approach to the deficit that is more than simply opposing cuts. It has to be based on stoking environmentally sustainable growth and job creation: reducing the deficit as the economy grows. The preelection commitment to a four-year deficit-reduction plan is unnecessary and too rigid. The deficit has not sparked a crisis in the bond markets. Bond yields remain low because Britain is not Greece, but a country with a long record of honouring its public debts and a large pool of domestic savers who reliably mop them up. The principal concern of government should be to restore capital investment and to ensure sufficient demand to restore business confidence.

The alternative approach to “the deficit” is to ignore it. It should never be the object of policy. Why would any progressive manifesto consider it otherwise?

Further, the reason Britain is not Greece has nothing to do with having a “long history of honouring its public debts and a large pool of domestic savers who reliably mop them up”. This implies that the New Political Economy Network accepts the myth that the British government needs to finance its public spending by issuing debt. Nothing could be further from the truth despite the imagery that the government creates as puppets in the neo-liberal theatre.

The reason Britain is not Greece is because it is fully sovereign in its own currency whereas Greece is not. A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. A progressive agenda should start with the articulation of this point and tease out the implications.

These implications include the rejection of any neo-liberal agenda based on alleged financial constraints on government. Further, there has to be leadership in public debate that leads to the conclusion that the whole “gold-standard/convertible currency” practice of issuing debt to match net public spending is unnecessary and provides corporate welfare benefits (the bonds) to the top-end-of-town and allows them to receive risk-free annuities which do not advance public purpose in any way.

The citizens have to start appreciating that the bond markets are parasites on government and that the latter is in charge at all times. That should be the foundation of a progressive agenda and the New Political Economy Network is silent on it.

So when the New Political Economy Network says:

Labour bought the snake oil of neo-classical political economy. It must now discard it, and become an organisation at the leading edge of new economic thinking. It needs to develop a moral economy, based on a democratic covenant with the people and macroeconomic policies for investment and sustainable economic development and market growth across the regions of Britain.

I wonder if they are still keeping some of the snake oil in the form of a reluctance to take the fiscal myths head on. At this time, the British government needs to expand the deficit not reduce it. It needs to do this because there is significant idle capacity (labour and capital). I didn’t get the impression from the e-book that the New Political Economy Network were contemplating a head-on assault against deficit terrorism. The narrative read as if they were deficit-doves a position I do not find satisfactory as a basis for a progressive fightback.

They are clearly defensive when it comes to deficits saying:

The popular association of Keynes with budget deficits and an active fiscal policy is, however, misguided. Keynes argued that this policy was required in times of exceptionally low demand in the economy, as in the 1930s or currently; but it was not his preferred solution to what he termed ‘the economic problem’. In the ordinary run of things he would have preferred to run an economy by monetary rather than fiscal policy …

Over the next few years – in sharp contrast to the austerity policies of the coalition – the economy will need higher government spending on infrastructure: social housing, transport projects and the green industries of the future. Over the medium term, however, the monetary lever will be more important than the fiscal, as Keynes, by background a monetary economist, also recognised. A policy of fiscal Keynesianism based on boosting consumption – essentially the macroeconomic policy pursued by governments up to the mid-1970s – will eventually force demand to levels well in excess of supply and result in inflation.

The e-book thus insinuates that budget deficits are only to be used when demand is “exceptionally low” and typically the main aggregate policy response will be monetary to discipline inflation. That is, a deficit-dove position with neo-liberal overtones.

I disagree with this emphasis and fail to see it as a progressive macroeconomic position.

Budget deficits are required whenever there is a non-government spending gap. That will always be the case if the non-government sector overall desires to save. Given that it is preferable that economic (green) growth is associated with the non-government maintaining sustainable levels of indebtedness and having overall savings (to allow for risk management etc), this means that budget deficits are always required. It is possible that the export sector will be strong enough to allow for high levels of domestic activity without ever increasing private indebtedness. Then the public balance could be in surplus without undermining the prosperity.

But that situation cannot hold for all countries or even many. It is not the basis of a progressive position. Normally, budget deficits will be required.

In my view (of-course) this MMT insight should be the basis of a progressive attack on the orthodoxy. There is no inevitability that inflation will result if governments maintain high levels of demand and support private consumption. The trick is to understand that the deficits are also supporting net private saving (the other side of the consumption coin). Deficits beyond that support level do introduce inflation risk. But then who advocates that?

The starting point of a progressive attack then is to understand how the monetary system actually works and the opportunities it provides a sovereign government. I don’t sense that is understood in this e-book.

A reliance on monetary policy has allowed high rates of labour utilisation to persist even when the economy has been growing. Persistent labour wastage always indicates that fiscal policy is too constrained. The primary role of fiscal policy is to ensure high levels of spending are maintained to keep employment at high levels and underutilisation of labour at low levels.

The emphasis of monetary policy on price stability has been at the expense of a fiscal policy emphasis on employment stability. Proponents of inflation targeting claim that in the long-run real output growth will be favourable if inflation is stabilised but fail to convincingly explain why high levels of labour underutilisation persist.

It has been the basis of the abandonment of the full employment framework. There is much that I find compelling in the e-book but I consider that many of the reforms they are advocating will not be achievable unless they abandon the conservativism with respect to the deficit.

MMT criticises the orthodox ideology and challenges its claim that price stability maintained ostensibly via the creation of a buffer stock of unemployment is preferable to a policy environment where full employment and price stability is maintained via active fiscal policy with monetary policy passively setting a rate structure consistent with robust long-term investment.

Proponents of MMT argue that full employment can be maintained by the introduction of an open-ended (infinitely elastic) public employment program that offers a job to anyone who is ready, willing and able to work and cannot find alternative employment – that is, a Job Guarantee.

These jobs ‘hire of the bottom’ in the sense that the minimum wages paid which are not in competition with the market sector wage structure. By avoiding competing with the private market, the Job Guarantee anchors the nominal value of money and the economy avoids the inflationary tendencies of old-fashioned ‘military Keynesianism’, which attempts to maintain full capacity utilisation by ‘hiring off the top’ (making purchases at market prices and competing for resources with all other demand elements).

The major test of inflation targeting or active monetary policy (buttressed with passive fiscal policy) is whether it can achieve and maintain full utilisation of labour resources in a stable price environment. The evidence to date is that monetary policy has failed to deliver on this goal.

A progressive position will never in my view subjugate fiscal policy and promote monetary policy as the principle counter-stabilisation policy tool.

Conclusion

Anyway, my train trip is coming to an end and I am soon to catch the plane to austerity. I think there is a song title in that – “The Plane to Austerity”. Lyrics may follow.

I will not be in contact with my servers much in the next 18 hours or so and as a result moderation of any comments will be delayed. If you post a comment that has an external link then it will always be moderated. I will be able to approve such comments during the stopover in Singapore and later when I get to London. So patience is the key!

That is enough for today!

For your enjoyment, here are the lyrics to the Brooklyn Funk Essentials – Revolution was Postponed because of Rain

The underlying

immediate

political

socio-economic

and trigger mechanism causes

were all in place when

some nee-gro or the other got hungry

had to stop at the McDonald’s

had to get on the line

with the new trainee cashier

“uhh, where’s the button for the fries?”

so we missed the bus…Then the leader couldn’t find his keys

didn’t want some poor ass moving

his brand new 20″ and VCR

out his living room on the shoulders.

It was too late when the locksmith cameThen our demo expert Willie Blew got arrested

came out with his head hanging under his hoody

“Didn’t know they started doing that

for jumping the turnstiles,” he said.

“How many times must we tell you –

Don’t.. get.. caught.”

We voted against shootin’ him on the spot

In the winter we were all depressed

so we leaned our guns against the sofas

and listened instead to Tim Tim Tiree

singing about his dysfunctions:

“Sometimes I wonder if ah’ll ever be free

free of the sins of my brutish daddee

Like the cheating, the stealing, the drinking, and the beating”. . .The weatherman said the 17th would be sunshine

and it wouldn’t be too hot –

Tim Tim Tiree doesn’t like sweatin’

but that night the weatherman came on crying

saying he didn’t control the weather

that God was real

that he’s lucky He, God, didn’t strike him, the weatherman, with lightning

for taking the credit sometimes

and that he, the weatherman, was in no way responsible

for the hurricane coming

and that we, the viewers, should

pray Jesus into our hearts

before it was too late.Superbowl Sunday was out

all the women wanted

to see the game

and the men were pissed

at their insensitivityThe 20th was supposed to be a definite

we looked for some Bastille to storm

didn’t find any

settled on the armory instead

before they moved the homeless in…

“We’ll bum-rush it anyway,” I said

“It smells like a collection

of a thousand farts in there,” they said

So we waited for the approval of the city

contract to build a Bastille

which set the revolution back five years.Peace wanted to start the revolution on Tuesday

She was in a pissed-off mood

her tax return didn’t come in time for the rent

But they showed the We Are the World video

on cable that evening

and we all held hands

and cried to stop from laughing

and our anger subsided

Looking back, it could’ve been a plot

but there are more substantive plots to expose

than the We Are the World conspiracyNow we wait for the rain to stop

All forces on the alert

some in Brooklyn basements

packed in between booming speakers

listening to Shabba Ranks and Arrested Development

bogling and doing the east coast stomp

gargling with Bacardi and Brown Cow

breaking that monotony with slow movements –

slow, hip-grinding movements

with the men breathing in the women’s ears to

Earth Wind & Fire’s Reasons

and wondering what the weather will be like

next weekend.

Can anyone explain why the huge regular annual wage demands of the trade unions in the late 60’s weren’t a significant factor for inflation in the 70’s? This always seems to be neglected here, unless I have missed an article that addresses it. I always thought that public dis-satisfaction for the power of the trade unions is what allowed the neo-liberal mindset to take hold.

Interesting post here: http://pragcap.com/why-qe-doesnt-work

“Early last year, I argued that the textbook model of the fiscal multiplier is also baloney. In the February 9, 2009 Morning Briefing, I wrote: “I can’t think of a more tired old theory than the Keynesian notion that $1 of additional government spending will generate $1.5 of real GDP. This ‘multiplier effect’ is taught in every introductory macroeconomic textbook. Yet, it is both theoretically and empirically questionable.” I then went on to quote the supporting evidence for my view in an OECD working paper by Roberto Perotti titled “Estimating the Effects of Fiscal Policy in OECD Countries,” which is linked below.”

Are both the money multiplier and the fiscal multiplier myths?

Then he outlines a strategy

” If the monetary and fiscal multipliers are figments of the imagination of macroeconomic textbook writers, what works? Profits! The Fed does not create jobs. The Treasury can’t do it either. Profitable companies create jobs and expand their capacity to hire more workers when they are optimistic about the outlook for profits. Profitable companies can drive up the stock market even if investors aren’t doing so. They can do that by using their record cash flow to buy other companies and to buy back some of their shares.”

Is he right? If not then where is the flaw in the argument and the evidence to support it?

A clear and cogent analysis and of particular interest to me since I was reading the blog post in the Guardian you refer to just the other day. Thank you, Prof Mitchell.

ps. I do not think you are going to like the temperature much here in London but I hope you have a good trip.

Have a good trip. Take some protective equipment.

Give a word up to Red Ed Miniband and quick change Nick.

Maybe just let the Tories be. They are doing a fine job, tying a noose with their own slack.

@houseman: The big inflation in the 70s was essentially entirely due to the oil shock.

And public dissatisfaction with the power of the trade unions was certainly never an issue over here (this may be different in some countries with weird politics). My impression is that it is the other way around: factory owners were dissatisfied with the power of trade unions and managed, via influencing politics and media, to create the false impression that the public was dissatisfied. A lie repeated often enough finally caused members of the general public to adopt the falsehood as their own opinion.

Bill you say: “actual GDP growth has rarely reached the rate required to maintain, let alone achieve, full employment”. To my mind full employment needs aggregate demand and that could come from redistribution even if the money paid out was matched by enough taxation such that there was no deficit and no nominal GDP growth (due to deflation). You quite rightly bemoan the growth of the FIRE sector of the economy but the FIRE sector simply grows to accommodate the amount of money accumulated in savings. The long term deficits you advocate as a means to accommodating the non-government sector’s “desire to save” equates to accommodating the FIRE sector’s desire to grow. I wish the emphasis was on the taxation needed to shrink the FIRE sector and to restore the relative financial power of the poor. To my mind expanding currencies are no more than a tool for increasing wealth inequality.

Nicolai: I don’t know how you can say wage inflation had no effect. If you look at the UK’s inflation statistics, you will see inflation topped 10% in June 71, well before the first oil shock.

stone, you almost hit the nail on the head;

(minor quibbles about utility of distributing tax burdens to co-manage ag-demand AND nominal deficits, since any country pursuing stagnant growth is pursuing eventual suicide)

All these issues occur in a complex economy, but the thread running through all the points of contention is political will and aggregate awareness. There is always a conflict between perspectives on individual options and awareness by those same individuals of simultaneous group options. When unbalanced, that perspective discord is expressed as political conflict – and forced, political decisions are the result.

The only time groups make adaptive aggregate decisions is when they are adequately informed.

Then only time they’re adequately informed in when adequate interactions are occurring – which gets harder to maintain as population size scales up.

If you view any population as an analog-computing-system or network, it’s quite clear that group intelligence is always expressed as the body of messages passed between computing elements, which in this case constitutes public discourse. Once taking that perspective, it’s also clear that management of group intelligence reduces to maintaining adequate rates of message-passing, i.e., adequate interaction levels.

In response to Bill’s question, my suggestion would be for the entire field of economics to consciously switch from managing the single, arbitrary metric of fiat currency holdings, to conscious management of the required level of interconnectivity in national aggregates supposedly exhibiting group intelligence.

[To accelerate things, you could simply replace most current economics faculty with faculty specializing in analog-computing-networks, make all economics professors teaching assistants, and give ’em all a year to get acquainted with respective jargons.]

Until then, economics is, by default, always reverting to the non-scalable, Libertarian view that sequestering resources from one another within a group is the noblest sport, while totally ignoring the lead point of adaptive survival in social species – group survival among competing aggregates. It’s a simple point of logic that individual views alone cannot scale up to direct formation of a group that needs to be “greater than the sum of it’s parts” in order to compete with other, organized aggregates. End of story!

Roger erickson, I agree that in the present set up any nation pursuing stagnant growth is going to loose out to those nations pursuing expansion. I just think that economists need to start thinking about what is optimal for the global population rather than what will allow their nation to prevail over other nations to the overall detriment. To my mind if the world trade organisation was to dictate that in order to partake in global trade a nation had to have a non-expanding currency, then that would be a better starting point. Then nations would no longer compete on the basis of who could get the most money into asset price inflation.

Many thanks for pointing out the weakness of the Network’s proposals. They don’t seem really know how to move forward on the issue of Aggregate Demand and where ignoring the deficit fits in. Are we in danger of this timid document being taken seriously as a guide for policy?

stone: deficit reduction is in essence dictating that nations must have a “non-expandable” currency. It sounds as if you support the IMF position.

Note that during the period 50s-70s, there was very little asset price inflation. This was not due to a lack of monetary expansion, but a regulatory framework that, among other things, separated commercial and investment banking.

pebird: Anyone who held Disney stock between 1962 and 1972 would have seen huge asset price inflation. There’s usually a bull market going on in some asset class depending on what’s fashionable at the time…

stone says:

“I agree that in the present set up any nation pursuing stagnant growth is going to loose out to those nations pursuing expansion. I just think that economists need to start thinking about what is optimal for the global population rather than what will allow their nation to prevail over other nations to the overall detriment”

Stone, I think we’re talking at subtle cross purposes. Int’l competition between aggregates is exactly the variance that allows discovery of what does/doesn’t work better/faster/cheaper. It needn’t be to the detriment of all. We learn by copying what works, and discarding what doesn’t – all while accommodating geographic & other minor differences in context. Given sexual/other recombination, hybrid vigor is the majority method for disseminating adaptive mutations – whether at genetic, behavioral, cultural or market levels.

Without variance, there can be no natural selection – since there’s no diversity to select from. The “moment of selective power” now is centered on selection among aggregate models – make no mistake about that. We’re wasting far too much time sequestering uselessly local honeypots & ignoring natural selection of aggregation models.

It’s a vicious class war going on; it have not been any a failure of policies. The policies have been extremely successful in shifting wealth from the many to the few. A success story way beyond anyone could have dreamed of thirty to forty years ago when full employment had shifted power to the many on the labor market. If the left and especially social democrats and labor parties fail to recognize that it’s a class war that has hit them and that the opponents are ferocious class warriors that will not give an inch of what they have gained without a fight they will forever be losers.

The social democrats and labor movement that once was had no problems recognizing what it was about. It’s about power, it always is, the technical issue is secondary.

The sad thing is that in most of the industrial world the heirs of labor movement early on did choose the “wrong side” in the class war, albeit the winning side. But no one trusts a traitor, so by now they have burn the candle at both ends.

But to fight back it’s absolutely necessary to know and understand the core that underpin the neoliberal myths, to know and understand that the foundation is hollow.

What stone said here:

\”I just think that economists need to start thinking about what is optimal for the global population rather than what will allow their nation to prevail over other nations to the overall detriment”

If taken within the context of his other comments on this thread, that statement is borderline brilliant if the reader understands what is currently underway in an effort to solve the current unemployment problem in the US. The \’powers-that-be\’ are trying to inflate away a portion of the US debt while also pressuring China to allow the yuan to rise about 30%. In theory, this will create jobs via a rise in exports and a drop in imports.

Those jobs though will come at the expense of global purchasing-power on 3 fronts. 1) oil prices will rise as the value of the dollar falls. 2) as Chinese exports diminish globally there will be price inflation without wage inflation because competition for global market share will continue to maintain downward pressure on wages worldwide as seen over the past 30 years. 3) the value of all global savings that are invested in dollar-related assets will be eroded by inflation.

I suspect that this is along the lines of what stone is getting at.

Perhaps I should also add that this may well be the only way that the Democrats can keep the Republicans out of power in 2012. So, there is the age old ‘end justifies the means’ argument involved here. I try, however, to avoid counter-factual crap that reeks of coincidental benefits for the presumed benefactors. What is worth noting though is that an increase in exports in the US means an increase in competition with global wage levels so… although unemployment may decrease the distribution of wealth in the US will exacerbate as a result of this ‘inflate down the debt’ ploy, and, in the end those who need to benefit the least, will be those who benefit the most.

A simple guiding rule is that wages need to rise along the bottom layers of the global economy, not come down from from the the upper layers.

Raylove@ Wednesday, September 29, 2010 at 10:35

“that statement is borderline brilliant if the reader understands what is currently underway in an effort to solve the current unemployment problem in the US. The \’powers-that-be\’ are trying to inflate away a portion of the US debt while also pressuring China to allow the yuan to rise about 30%. In theory, this will create jobs via a rise in exports and a drop in imports.”

As you say this is a theory. In the process of experimentation, millions will lose their jobs the actual economy of real products and services will shrink. The US will be lowering it’s living standards to compete with China. To boot there will be a large transfer of wealth from the already impoverished to the already wealthy. Truly a wonderful strategy. Some more, as MMT adequately explains the US debt is an artificial and unneccesary construct.

Neil Wislon said: “Then he outlines a strategy

” If the monetary and fiscal multipliers are figments of the imagination of macroeconomic textbook writers, what works? Profits! The Fed does not create jobs. The Treasury can’t do it either. Profitable companies create jobs and expand their capacity to hire more workers when they are optimistic about the outlook for profits. Profitable companies can drive up the stock market even if investors aren’t doing so. They can do that by using their record cash flow to buy other companies and to buy back some of their shares.”

Is he right? If not then where is the flaw in the argument and the evidence to support it?”

Probably not right. It sounds like he assumes a supply constraint and no demand constraint.

Profits come from quantities (Q), pricing (P), and margins (Mar).

If company(ies) can supply enough now and in the near future, they won’t expand because it would probably lower the stock price. It seems to me in the USA there is Q problem because of budget problems for the lower and middle class. A lot of economists can’t comprehend that there might be demand constraints because their models are based on the post WWII experience.

Peabird: you say “Note that during the period 50s-70s, there was very little asset price inflation. This was not due to a lack of monetary expansion, but a regulatory framework that, among other things, separated commercial and investment banking.”

I thought that the 50s-70s period was the period when the Bretton Woods system was in place with the USD pegged as $30/ouncegold or whatever it was and other currencies pegged to the gold-pegged USD. So there was a very strong brake on asset price inflation. Even if there is no long term global asset price (or consumable) inflation (due to all currencies being nonexpanding) some nations will have expanding economies whilst others retract in line with which nation is providing what the rest of the world wants. The difference would be that it wouldn’t be distorted by monetary expansion.

rayllove and andrew wilkins, my guess was that the “powers that be/global elite banks” see China as the only credible threat to their power (as us lot ie the electorate are such manipulatable morons 🙂 ) and China can see very clearly how the “powers that be/global elite banks” are bleeding the world dry. The idea that the Chinese economy is only 1/6th the size of the US economy or whatever seems entirely based on the artificial USD/yuan exchange rate. If things were to continue as they are now for another decade and then say China was to say hand out the USD bonds held by state companies to Chinese workers and let them do whatever they wanted with them wouldn’t that lead to such a shift in the exchange rates that China would then have the global reserve currency and the ratio between Chinese and US wages would be the other way around. My guess was that just the looming possibility of such a scenario is what is scaring the “powers that be/global elite banks” into deficit reduction. Maybe the Chinese actually have a benign agenda of forcing the rich world to act in a more equitable manner. My point is that we could both have zero deficits and also have low unemployment/ proper education/health care etc if we simply taxed enough to match the spending.

To me what is most striking about the post 1970s period is how much poorer the poorest 10% of the world’s population have become. The expanding currency system seems to be perfect for transferring wealth from them to the richest 0.0001% of the world’s population.

Stone, redistribution/greater income equality would reduce the overall saving rate, but there’s still the paradox of thrift problem such that public deficits are needed to fund net saving, given trade balances net out to zero globally.

This is what Job Guarantees do, it’s a wealth welling/springing up rather than trickling/crumbying down.

Arguably there is a global need for the poorest to do the same, mabye augmented by richer world cashflows to support poorest world Job Guarantees, but the point is fiat currencies provide sovereign governments the policy tools to achieve this.

The worry for me is that quality of government/corruption in two thirds world governments, if you think our rich are bad, check out theirs!

Will Richardson: The parodox of thrift issue is avoided if the overall level of net saving is kept constant indefinately by a wealth tax and inheritance tax. At the inception of a fiat currency system you need a deficit so as to create a stock of money. Once that is done, then you never need to have a deficit again. The existing stock of fiat money can circulate indefinately just as silver pieces of eight circulated from 1500s to 1900s or cowerie shells were used in precolonial Africa or whatever. The idea that the stock of money needs to constantly increase year on year decade on decade seems madness to me. It has not happened for the vast bulk of history and is clearly causing awful problems after just the last few decades of it being done up until now.

stone:

If you have a growing population and a constant money supply, it will eventually result in deflation. If people can have their money gain value just by keeping it in their mattress they probably won’t invest it. I suppose that this would prevent asset price bubbles but it might prevent all sorts of other stuff like start-up companies and so forth. Perhaps assets do need to inflate at least a little bit on a constant basis. For example, land remains constant when populations are growing – this suggests that kind of asset inflation is real. The problem occurs when it inflates too quickly and crashes.

Stone,

To add to Grigory’s point that you need more currency to fund your country’s population growth…often what also can develop is a zealous desire by aliens (external sector) to obtain and hoard or even to try to use your own country’s currency.

If this is also not addressed monetarily it looks like it can straightaway lead to chaos and social strife within your domestic society (there becomes not enough money to go around).

Resp,

Grigory Graborenko and Matt Franko:- I think the supposed peril of deflation is the key piece of disinformation that defends the expanding currency set up (scam 🙂 ). In a non-expanding currency system deflation will always be limited. If say each currency had a fixed one trillion units each unit with a serial number and matched levels of tax and spending kept all one trillion in circulation- then even if half of that money was horded that would only be a 50% reduction. What is more the hording would have increased the scarcity value of money for investment. That would have driven up potential earnings from investment so making it much less likely that people would hoard money. The same is true if the population increases two fold or even ten fold. Loaves of bread simply cost half (or one tenth) as much in nominal terms but so what. It is value that matters not the nominal units of currency. Reductions in the nominal amount of currency just increase the value per unit. People will invest if the investments make earnings even if asset prices are deflating. People invested in the industrial revolution in the 1800s because the investments made great earnings because they were providing a valued utility. People malinvested in the Irish property bubble up to 2010- building houses that still have not been occupied- because asset price inflation blinded them to the reality that the investment would never make earnings but they wanted to jump onto a ponzi escalator. If there is a limited stock of money, then money for investment has scarcity value and that means that it will be wisely used and only employed where it is going to get maximal earnings. I’m proposing having a wealth tax (ie to legally own something such as cash, real estate or stocks you need to show that you have paid tax on it for the past year) that will mean that people will know that if they just keep money in a giro account then they will have it eroded by tax. However money for investment would have scarcity value and so earnings from investment would be there to be had. Under the current system the amount of money available for investment is so bloated and increasing that earnings (dividends, rents, interest whatever) are becoming an insignificant part of what investors look to. Instead they are left chasing asset price bubbles. That is a disaster because it is earnings that relate investment decisions to the real economy’s needs in terms of rational resource allocation. The idea that deflation in the prices of consumables or services could be a problem is even less credible. Computers have had astonishing levels of price deflation ever since they were first invented. That may have made people sometimes wait until they needed a computer before buying one but that is a good thing. Deflation leads to peoples’ labour and natural resources being given due value.

Stone,

“Loaves of bread simply cost half (or one tenth) as much in nominal terms but so what.”

How do people (for instance young persons), who do not have a previous stock measure of money hoarded away, obtain the money to buy the discounted bread to eat when they are thrown out of their jobs? Thievery? Prostitution? Blackmail? Intimidation? Beggary? Take your pick.

Suggest you look at ancient Judea under the Roman currency system right about 2,000 years ago for your case study.

Resp,

Matt Franko, Asset price deflation would not lead to loss of jobs if government spending meant that there was plenty of aggregate demand. I’m totally for government spending to create aggregate demand to create jobs. I’m just saying that that government spending needs to be matched by a wealth tax and inheritance tax.