I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Household saving falls but private saving increases – Japan!

In recent weeks I have received many curious E-mails about Japan all asking the same question – if net exports are positive and households saving are in decline, how come the budget deficit is so big? It is a good question and the answer relates to developing a good understanding of the components of the National Accounts and the way they interact. As I explain here, the private domestic sector is increasing its saving in Japan but it is all down to the corporations sitting on huge piles of retained earnings and reducing their investment. What these trends tell anyone who appreciates the way in which the macro sectors interact is that sustained budget deficits are required in Japan and any move to austerity would be disastrous.

Last Monday (January 31, 2011) I wrote this blog – Please note: there is no sovereign debt risk in Japan! – which seemed to lead to a rush of Japan-focused questions along the lines outlined before. That blog was about whether Japan might default on its public debt. My previous blogs about Japan have been about how their experience grossly violates the main findings of mainstream macroeconomics and the fringe dwellers like the Austrian School.

It was not a blog about whether successive Japanese governments have administered their economic responsibilities very well. It was not a blog about inequality or poverty. It is clear that poverty rates as conventionally measured have been rising in Japan. You might want to consult the most recent major OECD study – Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries – to see how Japan is now exhibiting poverty rates around those common in the United States. It had the fourth highest poverty rate among OECD countries in the mid-2000s.

Does that mean fiscal policy has failed? Yes, but only because it hasn’t been expansionary enough! The decline in wealth in Japan began with the property crash which was a time when the government was running very low budget deficits.

It was not a blog about rising part-time employment in Japan which is clearly occurring and helping to undermine living standards. Like most nations, Japan adopts the ILO Labour Force guidelines and counts part-time workers as being employed. The incidence of part-time work and underemployment in Japan is rising but still below Australia, for example. This Australian Productivity Commission report – Part Time Employment: the Australian Experience – (especially Chapter 2 and Appendix A) has useful international comparisons.

It was also not a blog about saving behaviour in Japan – which I will come back too.

Later last week, I received one comment which I declined to publish because it was in contravention of my Comments Policy. As an aside, I don’t care what you say about the argument I am making as long as you back it up with a good counter-argument and stay on topic. I won’t publish a comment that seeks a podium for general mainstream thinking (or Austrian school raving) and refuses to address the specific issue.

I also won’t publish comments that question my sanity, accuse me of taking drugs and otherwise attack me as a person. My declination in this specific case was followed up by two further abusive comments from the same person which I similarly deleted. I note that the person involved is a contributor to a leading Austrian School WWW site and predicts that in 2011 Japan will default on its public debt and experience crippling inflation. I do not think either event will occur.

At no point did the person in question actually assess the argument being made that there is no sovereign risk in Japan.

But despite all that the person did raise some interesting points – or rather bald-face assertions most of which turn out to be factually wrong or misleading when you examine the data. That is not uncommon among the inflation-obsessed, governments-stealing-our-wealth Austrian schoolers.

But taken together with the other polite questions I have received of a similar vein I thought I would offer the following which looks in more detail about the saving behaviour in Japan.

The basic point is that if the Japanese government had have continued their planned deficit reduction in 1997 and not provided further fiscal stimulus to the economy the situation would have been significantly worse than what it already is. When I say we need to look to Japan to see a living example of how persistent budget deficits do not cause interest rates to rise and do not cause hyperinflation I am in no way saying that the conditions on the ground are good.

Given the behaviour of the private sector in Japan, the situation will continue more or less as it is now unless the government provides further fiscal support. I realise there is a debate about how they might do that given that you can only build so many highways. But with an ageing society comes a greater demand for personal care services and that is one labour intensive growth area that should be targetted.

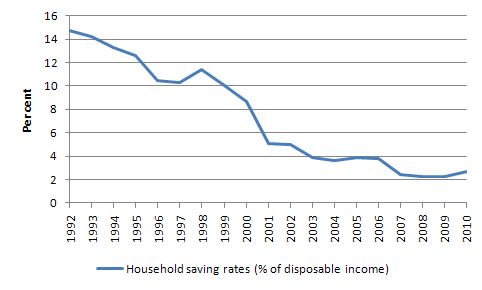

The following graph is often published as a sign of decay in Japan. The data is from the OECD and shows the household saving ratio since 1992 as a per cent of household disposable income.

If you go back to the blog in question – Please note: there is no sovereign debt risk in Japan! – you will find that I said

The fact is that the Japanese economy has required significant support from budget deficits over a long period given the relative high propensity to save by the private domestic sector.

My friend (the deleted commentator) however said that I was making “some ridiculous comments about Japan’s savings?” and in a relatively more polite manner said “Once again, you are talking out of your hat. 20 years of deficit spending and nearly zero interest rates have decimated savings in Japan and Japan now has a lower savings rate than the USA. Google search it”.

So does the household savings graph support this attack? Clearly not. If I had have said the household saving ratio was rising or households had a high propensity to save I would have been wrong. But that is not what I said. It is clear that the household saving ratio has been in decline and anyone (whether you live in Japan or have never been there – I am in neither camp) would know that without the aid of Google – all the major National Account database subscriptions (even before Google) show that.

You can read an interesting OECD statistics brief – Comparison of household saving ratios: Euro area/United States/Japan – for further information.

There are many reasons given for the decline in the household saving ratio. First, technical issues have helped reduce it since 2000. There was a major changes to the System of National Accounts (SNA) around then which led to major upward revisions in the private consumption expenditures (other than imputed rents of owned houses) and a significant downward revision in household disposable income.

But there are also underlying behavioural factors that have led to that outcome. The Japanese population is ageing and it is well known that as income flows decline people maintain their consumption by drawing on their financial assets.

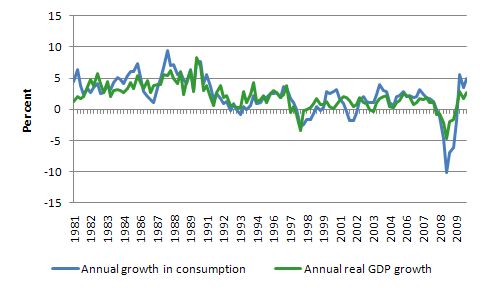

Has the declining saving ratio translated into a rise in consumption? Answer: no. Growth in real consumption has been flat for many years. The households are not engaging in a consumption boom – and that is one of the reasons the budget deficits have had to be so large.

The following graph (taken from OECD National Accounts data) shows the annual growth in real consumption and GDP since 1981.

Other factors that have been influential relate to policy changes in Japan aimed at reducing the government’s fiscal exposure to the ageing population. So there has been an increase in pension eligibility age and a decrease in retirement pensions etc which have contributed to the computation of the falling saving ratio.

But whatever the reason, the declining household saving ratio is evident. However, it doesn’t tell us that the persistent budget deficits have been detrimental. Far from it.

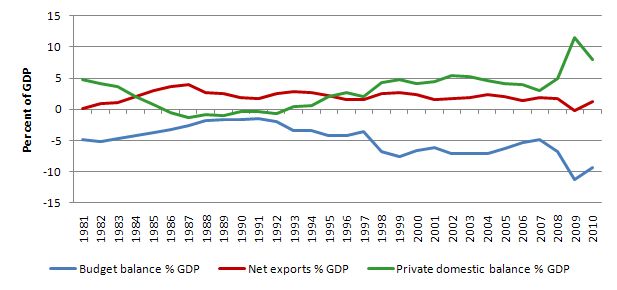

Now consider the following graph which shows the sectoral balances derived from the Japanese National Accounts. You can get reliable budget data from the Ministry of Finance. I used OECD Main Economic Indicators for the net exports data. The private domestic balance is then computed so as to ensure the balances add to zero as per the definitions in the National Accounts.

For readers well-versed in the sectoral balances skip the next section and go to the analysis. For others, you might like to refresh your understanding by first reading this blog – Twin deficits – another mainstream myth – for a derivation of the sectoral balances and more background material. Given I have derived these relations regularly I only summarise them below.

The sectoral balances are:

- (T – G) = budget balance, where T is tax revenue and G is government spending. A budget deficit would be a negative number.

- (S – I) = private domestic balance, where S is total private saving and I is total private investment.

- (X – M) = external (trade) balance, where X is total exports and M is total imports.

If (T – G) > 0 then there is a drain on aggregate demand via the public sector. If (S – I) > 0, then the private domestic sector is saving overall and this creates a drain on aggregate demand. If (X – M) > 0, then net exports are positive and this would add to aggregate demand via the foreign sector. Further, by implication, external deficits drain aggregate demand from the economy and budget deficits add aggregate demand.

These balances are linked via a strict accounting relationship which is derived from the National Accounting framework such that:

(S – I) + (T – G) – (X – M) = 0

You can then manipulate these balances in many ways to tell stories about what is going on in a country.

One way of writing the balances to show the relationship between the government and the non-government sectors:

(G – T) = (S – I) – (X – M)

That is a government deficit (G – T > 0) has to be associated with a non-government surplus, which can be distributed between the private domestic balance and the trade balance. The causality of that association depends on the context.

Another way to “view” the sectoral balances is to express the external position against the domestic position:

(X – M) = (S – I) – (G – T)

So if there is an external surplus (X – M > 0), then the right hand side also has to be in surplus. So if the budget was balanced (G – T = 0) then the private domestic sector would carry that surplus (S – I > 0).

You can then imagine what might happen if the private domestic sector increased their overall saving. In the first instance either consumption or investment would fall and the decline in aggregate demand (spending) would lead to a contraction of national income for a given fiscal and external position.

The only way the economy can continue to grow in these circumstances is if net exports increases and/or the government deficit increases. That is exactly what happened in Japan after the property crash in the early 1990s.

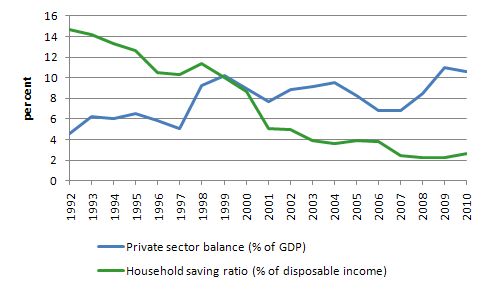

This graph compares the household saving ratio (green line) with the private domestic sector balance (blue line). The two are moving in opposite directions.

So the private domestic sector has been increasing its saving overall despite households saving a lower percent of their disposable income. What is the explanation for this? The answer is simple: corporations are retaining more of their earnings than ever before.

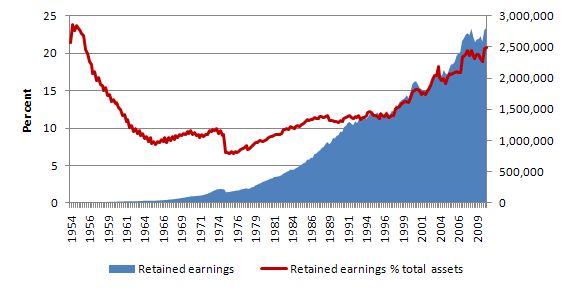

You can get historical retained earnings data from the Japanse Ministry of Finance. The following graph shows the rising ratio of retained earnings to total assets (left-hand scale) and the actual evolution of retained earnings (right-axis). Retained earnings have also risen relative to nominal GDP over the last 30 years.

So the overall private domestic sector is “saving” an increasing amount.

The Financial Times economics columnist Martin Wolf wrote an interesting piece last year (January 12, 2010) – What we can learn from Japan’s decades of trouble – which bears on our discussion.

Wolf refers to the work of Richard Koo who argued that when there is a “balance sheet recession” where an overindebted economy starts to pay down its debt:

… the supply of credit and bank money stops growing, not because banks do not wish to lend, but because companies and households do not want to borrow; conventional monetary policy is largely ineffective; and the desire of the private sector to improve balance sheets makes the government emerge as borrower of last resort. As a result, all efforts at “normalising” monetary and fiscal policy fails, until the private sector’s balance-sheet adjustment is over.

Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

As Wolf notes you can understand this in terms of the “sectoral balances between savings and investment (income and spending) in the Japanese economy”:

In 1990, all the sectors were close to balance. Then came the crisis. The long-lasting impact was to open up a massive surplus in Japan’s private sector. Since household savings have been declining, the principal explanation for this is the persistently high share of corporate gross savings in GDP and the declining rate of investment, once the economy went “ex growth”. The huge private surplus has, in turn, been absorbed in capital outflows and ongoing fiscal deficits.

Without those fiscal deficits providing the essential spending support for the Japanese economy there would have been a very ugly contraction in national income (as we saw in 1997). The poverty rates would have increased much more than they have.

The doomsayers who try to impute the causality as the on-going deficits leading to poor economic performance which would be reversed if the government pursued austerity just do not understand the macroeconomic intracasies.

As Wolf says:

… those who criticise the fiscal deficits miss the point. Without them, the country would have fallen into a depression, instead of a prolonged period of weak demand. The alternative would have been to run a bigger current account surplus. But that would have required a weaker exchange rate. Japan would have had to follow China’s exchange rate policies. The US would surely have gone berserk.

As long as Japanese corporations continue to save and restrict their investment there will be an on-going need for large fiscal deficits. The alternative – the austerity route is too grim to even think about. You don’t have to be living there to know that.

I don’t care to comment here on issues relating to “corporate control” which Wolf thinks is necessary to “to shift cash out of the hands of sleepy managements” and stimulate domestic growth. But until private spending increases, public deficits will be required and the public debt ratio will rise.

There is no cause for alarm in the latter trend. However, clearly the private sector in Japan is still in shock after the property collapse in the early 1990s and government might usefully consider policies that will assist.

The important point is that those who want to claim that the sustained fiscal deficits cause massive crowding out via high interest rates or “soaring inflation” are missing the point entirely.

Conclusion

My friend the commentator also made a fundamental error when he said that “I couldn’t disagree more with this Keynesian madness you spout off. Twenty years (now heading on thirty) of this deficit spending nonsense has gotten Japan nowhere”.

Well I don’t write anything that could be labelled “Keynesian”. It would be better if people were more precise in their use of terminology. I have actually written several academic articles criticising what I accurately denote to be Keynesian thinking.

But his claim that the sustained deficits have caused the lost decade and then some are missing the point. The crisis came and with it the need for rising deficits. The latter have supported modest growth. Everything isn’t fine in Japan – far from it. But it would have been much worse had Japan followed the austerity route that the Austrian school love to advocate from behind the safe walls of secure, well-paid jobs.

And once again – there is no risk of sovereign default in Japan. They can go on deficit spending for years and should do so as long as the private domestic sector is holding huge pools of saving and are resistant to spending.

That is enough for today!

In case anybody wants to compare I drew up the UK sectoral balances over the weekend.

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2011/02/uk-sectoral-financial-balances.html

“But until private spending increases, public deficits will be required and the public debt ratio will rise.”

Isn’t one of the issues across the globe that the government is actually subsidising the saving by issuing long term ‘corporate welfare’ bonds at a higher interest rate.

It’s fascinating that you hear loads about the ‘feckless’ individuals who ‘live on benefits’, but next to nothing about corporations that are doing exactly the same – and at several orders of magnitude greater.

The interest rate on government bonds clearly defeats any impact of loose monetary policy. The corporations are always going to take the risk free 4% corporate welfare on offer rather than undertake risky investment when demand is so weak.

It strikes me that besides the Job guarantee, the best thing a government could do is simply stop issuing bonds. Which should then force the corporations to re-evaluate their investment strategy.

I understand that government deficits are needed for private savings, but is it not correct that those deficits should be guided to labor rather than capital, unless a country is in shortage of capital? When people and corporations are linked togeather as private savings, then it is not necessary that private savings benefit the people at all.

It seems to me that in the US all the benefits of the deficits has gone to corporations and the wealthy who have used it for speculation and gambling. If allowed to go only to the few, at some point does the economy not move away from the masses to the wealthy and the large corporations? Does MMT not focus on where the money should go? If not, then would Ronald Reagon be considered a MMTer? After all, he did create deficits.

Neil Wilson,

I like your way of thinking.

However, if the govt does not issue bonds will it still have a mechanism by which it can stop the cash rate from approaching zero ?

Or is a zero rate target the intention ?

cheers

There’s been occasional commentary on MMT blogs in the past about the potential for the private sector financial balance construct to obscure the elements of its own decomposition. This blog is an example of why the decomposition of the private sector can be interesting.

In this case, the surplus position of Japanese firms has a directionally similar association with the household sector balance as that of a marginal government surplus. To the extent that the household sector has its own desire for net financial assets, that probably means that government deficits need to be all the higher.

“However, if the govt does not issue bonds will it still have a mechanism by which it can stop the cash rate from approaching zero ?”

It can pay interest on reserves as easily as it can pay it on bonds. Most of the world’s central banks seem to be moving towards paying interest on reserves to maintain the monetary policy rate (in the UK it is called the Bank Rate).

However there is no problem with zero – other than dealing with the political fallout from the ‘retired savers’.

Alan, Warren Mosler’s immediate proposal for the US is issuance of three month bills as maximum maturity. Longer term is a giveaway to rentiers, or as Warren puts it, a corporate subsidy. He also recommends setting the overnight risk-free rate to zero. See The Natural Rate of Interest Is Zero by Mathew Forstater and Warren Mosler.

Michael Hudson points out that any surplus over return on the factors that is not taxed away will go to economic rent. Taxation of economic rent and recycling it through government expenditure toward public purpose would discourage rent-seeking and encourage productive investment while building a strong economic base through education, health care, basic research and infrastructure.

JKH and others,

FYI, see my wp with Randy Wray at Levy from December–I broke down the US pvt sector balance in figure 2 there.

I have a question: why is there any inflation now in UK, with falling GDP. Inflation is around 3%. How is that possible in MMT framowork, absent increasing commodity prices? (and these do not climb, if they did they would cause inflation outside UK too, and inflation is very low in US, Japan etc).

Peter,

In the UK, the government have put up indirect taxation like VAT, fuel duty etc significantly two years in a row, and this will be a large part of the reason. Some is absorbed by companies, but probably most of it gets passed on to the consumer. I’m not sure what other factors come into play apart from food and fuel, but I don’t think anyone seriously thinks there is too much demand in the economy (demand-pull inflation).

Thank you, Bill, for this extremely enlightening discussion. The situation in Japan is one of great interest to all in trying to understand macroeconomics. Japan is clearly one of the more exteme situations and it’s economy provides fodder to support positions of all stripes, along with Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe.

Interesting graph, Scott.

The only previous episode that looks anything close to the recent double barreled spike is the 89-92 period.

Japan and some European nations cop all sorts of flak from the Growth At Any Cost propagandists because of the declining number and associated aging of their population. Some of the statements are so ridiculous one would think that the nations concerned are on the brink of extinction.In the case of Japan they advise immigration to an already overpopulated country.The Japanese are very wise to resist this,probably more for social reasons than for any notions about sustainability.

It seems that the concept of exponential growth is still not understood or acknowledged by significant sectors of the leadership,including economists.Populations must cease growing due to lack of resources and to the severe damage caused to ecosystems which we and our fellow passengers on Spaceship Earth rely on to survive.

When populations cease growing,even under the most benign of circumstances (unlikely in a lot of cases) then they will certainly decline,probably precipitously.

We are going to have to deal with declining populations or,in the best case scenario,a stable population.Like MMT,this is nothing to be afraid of.It actually opens up some very interesting and advantageous paths.

It would have been useful to discuss what these companies are doing with the retained earnings. Richard Koo explains that during the Japanese housing bubble years companies borrowed heavily using real estate as collateral. Since then, real estate prices have fallen 90% and their balance sheets are under water, so they are using retained earnings to pay down debt.

Peter,

inflation do not follow changes in aggregate demand, not at least directly. Price level is set by costs, most important being the wage level. Wage level is set by contracts, and declining wages are extremely rare in a modern society. That is why there is not usually deflation. Japan can have deflation because its labor unions accept wage reductions.

Can somebody put up the link or whatever Scott is referring to? Thanks!

Scott, can you do me a favor? Show the accounting for going off the gold standard in the 1930’s and show the accounting for not rolling over debt and the gov’t not being able to pay off the interest and principal. Thanks!

For the 1930’s, I think it is credit the demand deposit account of the person selling the gold and crediting the reserve account of that person’s bank 1 to 1. Is that correct?

JKH said: “There’s been occasional commentary on MMT blogs in the past about the potential for the private sector financial balance construct to obscure the elements of its own decomposition. This blog is an example of why the decomposition of the private sector can be interesting.”

More like necessary? Does that mean if the private sector wants to save then the gov’t sector needs to dissave is not enough?

Is it more like savings of the rich and rich corporations equals dissaving of the gov’t plus dissaving of the lower and middle class? Wealth/income inequality?

And, “In this case, the surplus position of Japanese firms has a directionally similar association with the household sector balance as that of a marginal government surplus. To the extent that the household sector has its own desire for net financial assets, that probably means that government deficits need to be all the higher.”

But should the deficit be in “gov’t currency” and not gov’t debt? Is there a difference between creating more “gov’t currency” and creating more gov’t debt?

I’m trying to understand the connection between firms de-leveraging, low household savings, and high levels of retained earnings. I wonder if this isn’t just an artifact of delayed recognition of losses.

Assume the firm has bank loans that it wants to repay, and instead of distributing earnings to shareholders it uses those earnings to pay down principle on its debt. In this case, the shareholders savings still goes up, but in the form of their equity claims on the firm. It shouldn’t matter whether a firm pays out earnings to you or re-invests, increasing your ownership stake, just as it shouldn’t matter if a firm buys back shares or pays out dividends.

But if the debt was bad — i.e. the firm suddenly swung into a negative equity position, then at that point household savings should become negative, or you can really argue that they were negative all along, but were incorrectly valued on the household balance sheet. So perhaps this is all just an accounting mismatch — the “true” household savings went hugely negative right in the beginning, and have been large and positive since then. The retained earnings by the firms really should be viewed as household savings to compensate for the dissaving that occurred when the bubble burst and the balance sheets were re-priced. Just a thought…

Firm saving adds to firm retained earnings (equity).

Household saving adds to household equity.

Household equity also incorporates changes in the market value of their claims, direct and indirect, on the retained earnings of firms.

So total household equity changes by what is effectively a market to market adjustment for (prior) claims plus an “accrual” for current period saving.

(The same accounting logic holds throughout finance and portfolio management. Even a bond portfolio is tracked in terms of market to market plus accrual effects. This distinction is sound accounting.)

Retained earnings, dividends, and buybacks can all produce very different patterns of risk and return to household balance sheets in terms of timing and eventual portfolio composition. Dividends are simply less risky than retained earnings, given the immediate option for households to stay in cash. Buybacks are often a disaster in terms of opportunity cost to investors (apart from option hedging programs).

I’d say that, notwithstanding the strong behavior of both corporate and household saving rates recently, the earlier stock market crash has so far been a drag on the otherwise beneficial effect of the two saving rates on household balance sheets.

I believe it’s corporate cash and not retained earnings per se that have been highlighted in the financial media for the most part.

I’ve been trying to get the Levy site to give me access to Scott and Randall’s wp for a couple of days now but its been unreachable from my part of the Internet.

Comment 16:18 applies to national accounts saving rates, in which sector net saving rates are embedded.

Scott’s paper, where his figure # 2 shows sector net saving rates:

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_645.pdf

Here is the link to the paper: link_http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1730744

I’m slightly confused by MMT’s view on rates. On the one hand, you hear “the natural rate of interest is zero”; and certainly the higher the level of govt debt / GDP, the more the govt needs to manage its blended interest rate towards zero (eg by only issusing 3mo maturities).

On the other hand, Mosler seems to have been referring recently to low interest rates as deflationary, or a tax on private sector savings. (A related point is that Scott F has in the past suggested that monetisation may actually (counterintuitively) be less inflationary than bond sales, since monetisation gives the private sector non-earning NFA as opposed to coupon-paying NFA.)

I would have thought that if a given output gap can tolerate a budget deficit of say 10% without making inflation accelerate, it’s better for this 10% deficit to be split 9% on targeted spending (with a proven multiplier effect) and only 1% on bond interest (which goes to capital owners and so has a low multiplier), instead of 7% vs 3%. In other words, if a govt pays out a lower amount of sovereign interest, it has more ‘room’ to pay for more useful things.

Any thoughts?

The one off fall of Sterling has given a one off push to prices, albeit that it’s bounced back a little, so mitigated that one off fall, to some extent.

if low interest rates are deflationary, that makes room for taxes to be lower

I’m puzzled by the idea that low interest rates necessarily help productive activities whilst higher interest rates help rentiers. The last few years seem to have been a bonanza for rentiers who were happy to adapt to a trading strategy rather than an interest accruing strategy. I don’t see how someone gathering money by rebalancing assets such as stockindex funds, commodity etfs and cash is any different from someone gathering money from holding government bonds paying a high real rate of interest. Simply sticking to a fixed allocation (in $ terms) as the markets chop about sucks money in to such people (and away from the rest of the economy).

JKH – I think you are saying the same thing: for a given level of deficit, and a given level of spending, a lower blended interest rate will mean lower tax is necessary to drain purchasing power to keep to stable inflation. But Mosler seems to regard the low interest rate as harmful, eg “The near 0% interest rate policy continues to suppress private interest income”

Anders,

Yes, I attempted to say the same thing.

Mosler’s point on harm is not internally inconsistent:

What he typically says along with that is that low interest rates SHOULDN’T be harmful net – because government should be reducing taxes in view of those low rates.

What ends up being harmful net is low interest rates combined with an inflexible tax policy – one that doesn’t respond appropriately to those low rates. That’s the context for his comment about harm.

This would also apply at the margin to his generic idea for a zero natural rate of interest monetary policy.

Anyway, that’s my rough interpretation of his idea here.

Think of lower rates on government debt as a relative NFA drain – offset by lower taxes as a relative NFA add.

JKH – that reconciles it. Thanks!

“So the private domestic sector has been increasing its saving overall despite households saving a lower percent of their disposable income. What is the explanation for this? The answer is simple: corporations are retaining more of their earnings than ever before.”

Has anyone broken this down into the financial and non-financial sectors?

Thanks for the links!!!!

Fed Up – which country? The UK’s ONS is pretty good on this stuff – google “Table 1.12 Summary capital accounts and net lending/net borrowing”. That table splits out HH from financial and non-financial corporations.

Anders, Japan.

Not sure if I’ll get a response after nearly a year, but I’ll put something up anyway.

I completely agree with the first half of your argument about savings increasing first and requiring deficits to avoid a depression, rather than the deficits crowding out investment. However, I don’t think it therefore follows that Japan is in no risk of default.

Looking at Japan’s budget shows that nearly half of all tax revenue is consumed in interest payments. Given Japan’s demographic issue have not been solved and don’t look like being solved anytime in the next three decades at least, it seems reasonable to suppose that the current deficit spending will have to continue for at least that long. By then well over 100% of tax revenue will be spent on interest repayments if the current situation continues. Do you think that Japanese investors will continue to invest in Government bonds under such conditions? Or will they being to seek higher returns and safer investments in foriegn assets?

Another point is that as Japan’s population decreases and ages, it’s reasonable to suppose that the Government will use a higher and higher proportion of savings. Let’s assume they’ll only do enough stimulus to preserve real GDP/capita (i.e. marginally falling real GDP). Based on S+T=I+G+(X-M) suppose that I and (X-M) fall marginally and G remains flat to accomplish this goal, then S+T will decline. In the next year, with lower S+T accumulated from the first year and flat G, G will require a higher proportion of S+T etc, etc. Does it not follow that eventually there will not be enough S+T for G to remain flat without crowding out I or X-M? This would result in higher interest rates and would also mean there’d no longer be any point in providing the stimulus. This point is largely a theoretical one to show the possibility of crowding out in Japan and in reality is a long way off.

My real interest, though, is in your response to the issue of savings being funnelled offshore resulting in the Japanese Government not being able to get sufficient capital to fund its deficits and being forced to print, default, or, if the scale is small enough, engage in austerity. History tells us that the first two options always end badly, and the third option is simply the one that the spending was aiming to avoid. The third option would also probably have to be done much more harshly than it could’ve been done 15 years ago.

History tells us that the first two options always end badly, and the third option is simply the one that the spending was aiming to avoid.

History doesn’t tell us that. In fact, I read an article where it was announced that the UK had already passed Weimar Republic’s levels of financing through currency creation, and that the US was nearing at an alarming pace. Yet, inflation is under control in these two countries.

Another historical example would be Nazi Germany, which managed to obtain an unparalleled economic recovery by the extensive use of currency creation.

This blog has a very good post on Zimbabwe, if you use that search tool at the very top of the page and search, you’ll see an explanation of Zimbabwe’s example.

I’d be interested to see the article on the UK and US. When you say “levels” I presume you mean something like “as a percentage of GDP” or similar, rather than absolute values. Obviously, this would be the only way that it would mean anything.

Regardless, there are two problems with these examples in terms of what I meant. Firstly, they are not yet “history”. That is, we don’t yet know that the UK and US won’t have problems with inflation as a result of their printing. Secondly, I was talking about situations where governments can’t get sufficient funding from bond markets and print in preference to defaulting or slashing expenditure. Neither the UK or the US printed because they couldn’t get the capital from the bond market, so the situation that I suggested Japan may arrive in is not analogous to the US or UK currently. As such, I stand by my claim that history tells us that the first two options always end badly.

Hi,

thank you for the really informative article.

I am just curious. You say that you are not at all interested in Keynesian ideas. It seems to me though that what you are describing is very similar to what Krugman is talking about when he says that Japan is experiencing troubles due to a liquidity trap, which is a Keynesian idea after all.

I can see that there is a difference in what Krugman prescribes as a solution, but otherwise the problem seems the same. It would be fantastic, if you could outline me the differences.

Thanks,

Sebastian