I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

National output gaps matter

A Reuters market analyst (John Kemp) has created a stir by effectively declaring that the global economy is governed by some global NAIRU – a non-accelerating rate inflation rate of unemployment – such that the advanced economies cannot reduce their unemployment rates by expansionary fiscal policy and major structural reforms are needed. In a recent article – Mind the global output gap – he argues that “(e)scalating food and fuel prices are a sign the global economy is approaching full resource utilisation and the limits of sustainable output”. He claims that the “high unemployment and idle factories” in the advanced economies are not a sign of a “cyclical lack of demand’ but rather reflect “structural shifts”. From a policy perspective this is natural rate theory on a global scale and effectively denies that sovereign governments can influence domestic demand and real output (within their own policy boundaries) through aggregate demand management. This is the ultimate neo-liberal denial of the effectiveness of fiscal policy. It doesn’t stand scrutiny as you might expect.

Kemp says:

… a quick look at the global picture makes it clear that the problem is structural (distribution of demand) rather than cyclical (lack of demand at a worldwide level).

Yes, I might add a very quick look. His quick look (and subsequent outrageous claim) consists of examining an industrial production index (base year 2000 = 100) which is derived from the Dutch Centraalplanning bureau (CPB) a government agency that generally puts out very mainstream (neo-liberal) research and has heavily promoted the NAIRU-myths over the years. Kemp claims that the CPB are “one of the most respected trackers of global output and trade flows”. It all depends who you ask.

I have written papers in the past with my Dutch colleague Joan Muysken exposing how slippery this organisation (the CPB) is with their data usage. In several cases we have explored (using their data) we were able to produce very different econometric modelling results compared to their published output by varying sample sizes. In some cases, so called “structural variables” which they claim “cause” unemployment (like replacement ratios, tax wedges etc) were full of cyclical noise. Once we took the cyclical frequencies out of the time series the so-called structural variables ceased to be statistically significant in the models. In other words, the results the CPB produce are often very suspect and tainted. I could go on … the measure of it is that I would not conclude they are very respectable!

The CPB Industrial Production index is contained in its World Trade Monitor database, the most recently published being November 2010. It is a volume indicator and has been typically used as a coincident indicator of world trade activity – one of many such indicators. You can find studies that compare how accurate these indicators are and you will soon appreciate that results and predictions vary depending on which indicator you choose.

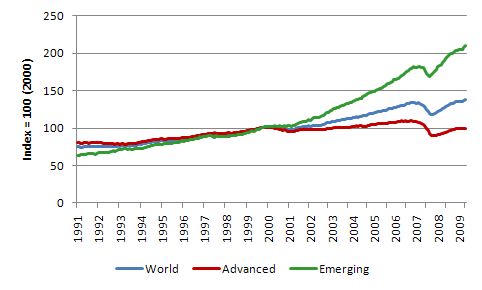

Anyway, here is the graph that Kemp provides as his “quick look” at the global picture. It shows the CPB industrial production index for the World, the advanced economies (essentially OECD excluding Turkey, Mexico, Korea and Central European countries) and the Emerging Economies.

Kemp concludes from this chart that:

Central bank officials and commentators in the United States and Europe focus on the persistence of an “output gap” in the advanced economies. But the chart suggests there is no output gap in emerging markets. For the world economy as a whole, the output gap is probably small or non-existent.

Okay, assuming this data is an accurate depiction what can it tell us? Does it support Kemp’s rather dramatic conclusion?

The reality is that the graph tells us nothing more than the following – the emerging countries have recovered from the recession much more quickly than the Advanced nations and the gap between the two growth rates is widening.

Anything else? For example, does it provide any information about how close these nation groups are to potential productive capacity? Answer: nothing at all. There is no supply side information that can be independently deduced from this data.

So can Kemp conclude from this data that the unemployment problem across the world is “structural (distribution of demand) rather than cyclical (lack of demand at a worldwide level)”? Answer: absolutely not! There is no information in this chart that allows you to conclude that. In other words, he is just asserting this on the basis of some price rises in commodities in recent quarters.

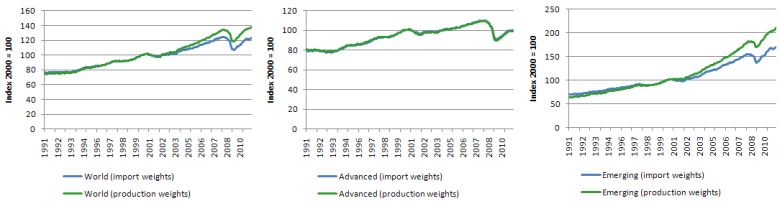

Some further points to note. Kemp plots the data on the basis of production weights rather than import weights – the CPB provide data for both. The series are somewhat different if you use the import weighting especially for the emerging economies. Consider this graph which compares the two weightings for the three groups (World, Advanced and Emerging).

The debate about which weighting system to use is complicated and beyond this blog. But the point I want to make is that in any exercise where the data can be presented in more than one way you should be cognisant of the fact that the results can be very different depending on the choices made. In this case, the industrial sectors in the Emerging economies are growing more slowly if we consider the import weighted version of the CPB series when compared to that picture presented when we present the data using the production weights.

Further, you will notice that the series excludes the construction sector from the goods-producing (industrial) index. The construction sector is heavily dependent on domestic demand and has little traded-good exposure. The point is that the the CPB industrial production index is focused on predicting trade movements and doesn’t tell us much about capacity limitations or usage in any domestic economy.

Moreover, this is emphasised by the fact that the CPB industrial output index is a volume index focusing on the goods sector and excludes the service sector output. So even though manufacturing, for example, might be growing strongly and reaching capacity, there can still be scope for the economy to expand services when there is idle labour. The services sector typically requires less additional capital for expansion. The graph Kemp presents tells us nothing about the performance of the service sector which can be targetted by expansionary fiscal policy to provide many jobs in labour-intensive activities.

So I laughed when I saw the claims spreading through various financial market blogs that we had reached global capacity – because John Kemp had said so – based on a quick glance at a picture that is incapable of telling us anything about capacity.

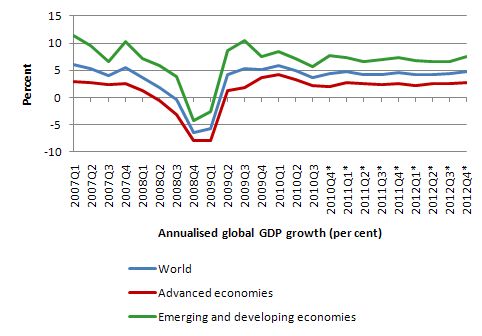

Then consider this graph which is taken from the January Update to the IMF World Economic Outlook (I reproduced it from this data).

If this graph is accurate then while the Emerging and Developing countries have resumed growth and their growth rates are much higher than the Advanced economies, they are still below the pre-crisis peaks. The point is that this graphic would not suggest they are near capacity yet.

Kemp’s main claim is that observed increases in:

… commodity prices, tightening supply-demand balances, and falling inventories, tend to confirm that the global economy is nearing its maximum sustainable output, at least in the near term … In this context, it may not be possible to use fiscal and monetary policy to make advanced economies grow much faster and reduce unemployment without triggering big increases in the cost of food, oil and other industrial raw materials … Only increases in productivity, reductions in real wages and incomes, weaker currencies and a shift into higher-value adding businesses can solve the problem of mass under-employment.

According to this view the recession was just the “painful reverse side of globalisation” and the rising unemployment that occurred was a “structural shift” whereby the “increased integration into the world economy” of the emerging nations “means more competition for resources and employment in the advanced economies, and reduced living standards for households and firms which compete most directly with rivals in developing economies. Globalisation is creating losers as well as winners”.

Conflating the cyclical effects and the longer-term structural effects is problematic. I agree that the challenge ahead for advanced economies is the increased use of energy by the emerging economies particularly China. In this blog – Be careful what we wish for … – I argued that the workers in the advanced economies who had enjoyed cheap energy (to heat their houses and fuel their cars) will lose out in the competition for this energy to the rising middle classes in the emerging economies.

But that doesn’t replace the major cyclical impacts of the collapse in aggregate demand that explains the rise in unemployment since 2008. Structural shifts do not occur in such a short-time period with such savagery and they do not tend to be closely correlated with shifts in aggregate demand.

The challenge that the global economy has to face with the changing demands for energy as previously poor nations become rich does not reduce their capacity to use fiscal policy to improve general well-being within their own borders. The growth of China and the other emerging economies and their increased demand for resources does not mean that governments in advanced nations have lost their scope for increasing domestic employment?

What it means is that competing for resources which are already in high demand is likely to contribute to inflationary pressures. It also means that governments may have to use their fiscal design to alter the composition of resource usage while at the same time ensuring the level of demand (or its growth rate) remains sufficient to provide enough jobs for those who wish to work.

The fact remains that the government can always deploy resources that are available for sale in the currency of issue and for which there is no market bid. The existence of huge pools of idle labour signals such a resource.

Kemp says that “(s)tructural shifts are not new” and points to the decline of agriculture in C19th Britain and other examples of how global shifts in production harm nations. He says that:

The point is these shifts were structural, not due to lack of demand. Attempting to reverse them by boosting government spending or cutting taxes and interest rates would not have resulted in long-term gains unless it was accompanied by competitive devaluations of the exchange rate and protectionist measures — precisely the retreat into autarky which intensified the Great Depression in the 1930s.

Underpinning his thesis is the implicit notion that fortunes are won and lost via changing trade patterns. They are not. Sure enough capitalism is about seeking out cheap labour sources to extract as much surplus as possible and there is no loyalty to national boundaries which are the limits of sovereign governments.

But as noted above, the traded-goods sector is a small proportion of the overall economy. And while many sectors rely on imported capital in some nations, there are many activities that can be targetted by a well-designed fiscal intervention which are still more than capable of expanding and absorbing the idle labour resources available in the Advanced world.

Leaving an economy to the dictates of an unregulated private market to make all allocation decisions is a sure way of exacerbating the impacts of the global shifts in production. But an enlightened government should see that for every job lost to an emerging nation – notwithstanding the adjustment burden borne by local communities that lose the jobs – there is a worker freed for other pursuits. The role of government is to ensure that there are new job opportunities and adjustment assistance when these compositional changes impact.

Kemp actually notes exceptions:

With some exceptions, such as Germany’s precision-engineering and capital goods industries, the same hollowing out (now called off-shoring) is occurring across much of the North American and European manufacturing and service-producing sectors.

The exception is important because it indicates a different cultural attitude and different policy stances by the governments involved. More interventionist governments foster productivity growth without hacking into wages and conditions whereas other more laissez-faire nations fail in this regard.

Kemp claims that:

Policymakers and commentators are still focused too much on measures of unemployment and spare capacity within individual economies. But in a globalised economy, it makes little sense to focus on national output gaps.

Commodity prices and other forms of inflation are driven by the global supply-demand balance rather than joblessness and silent factories at national level.

Policymakers can try to re-allocate demand from one country to another by manipulating exchange rates … But competitive devaluation is not feasible for larger economies such as the United States and the euro zone — and it cannot be pursued by all countries at the same time, otherwise it will become mutually self-defeating.

In a global economy with little or no spare capacity overall, particularly in the natural resource sector, a strategy of monetary expansion and competitive devaluation will simply result in accelerating inflation.

There is no doubt that global demand and supply forces condition commodity price movements. But that doesn’t lead one to conclude that “national output gaps” should not be a source of policy focus. The implicit sentiment here is that the only policy concern should be inflation and that because globalisation has broadened the inflation-generating mechanism beyond the interplay of national demand and supply forces we should conclude that all national unemployment is structural.

I also agree that competitive devaluations will fail as they have in the past. But none of this tells me that fiscal policy has reached the end of its limits of effectiveness.

None of this tells me that the US has 10 per cent structural unemployment. None of this tells me that if the US government announced a Job Guarantee tomorrow and offered work in the community sector that productive output would not be forthcoming with little impact on the price level.

Further, in the Emerging and Developing economies there are millions of idle workers and no shortage of resources to deploy to bring these workers into production.

The ILO Short term indicators of the labour market tell me that there are extensive idle resources in the emerging economies.

In the recently released (January 25, 2011), the Global Employment Trends 2011: The challenge of a jobs recovery (be careful the PDF document is 9.83 mb) – the ILO examine the “labour market situation during the recovery from the global economic crisis” and provides some sobering assessment of the distribution of excess capacity. The report demonstrates massive idle labour resources throughout the Emerging and Developing world.

Kemp is alleging that these workers cannot be productively employed – which means he is asserting that development has reached its limits under current circumstances? My work in developing countries tells me that there are a near infinity of opportunities for productive employment if the respective states are willing to use their fiscal capacity to target domestic production and service delivery.

For example, South Africa has abundant resources in the form of timber, concrete etc and more than 60 per cent of their population without work, income or adequate housing. Is anyone seriously going to argue that a large-scale public employment program designed to employ people building their own houses (in the first instance) and using locally sourced resources is not possible without driving inflation into an accelerating spiral?

Further, the analysis fails to acknowledge that fiscal policy has two major features: (a) it can alter the level of aggregate demand (spending) or the rate of growth; (b) it can alter the composition of final demand by targetting components of final demand – stimulating some components and restricting others.

It is this capacity to target expenditure components that is a significant advantage of fiscal policy over monetary policy which just affects all interest-rate sensitive spending. Fiscal policy changes can for example reduce the purchasing power of one income cohort while expanding the purchasing power of another cohort while at the same time tailoring overall aggregate demand to the desired level (relative to real output capacity).

Going back to our South African example – Kemp would argue that the extra demand for food of workers employed to build their own houses (relative to the spending possible when they were unemployed) will exacerbate the global demand for food and trigger inflation. First, demand for food might rise and in the case I am using that would be desirable because poverty, joblessness and inadequate food consumption go together. Second, if the world is truly at its capacity to produce food (and I doubt that seriously especially given the extensive capacity to re-use land for more efficient cropping – vegetable protein replacing animal protein), then the government can simply reduce the capacity of other income groups to consume food. Given the trend to obesity among the higher income cohorts that would also have significant health benefits.

How much extra demand would there be if workers in advanced economies were employed? This clearly depends on what income support arrangements are in place for the unemployed. In most advanced countries there are some income support provisions which are not that far from the minimum wage. If a Job Guarantee was introduced and workers paid a minimum wage then the extra demand would be relatively small. Should that push the economy beyond the inflation barrier (highly unlikely) then

The other major shortcoming in Kemp’s analysis (if we dare call it analysis) is that he fails to acknowledge that the underlying causes of the food price rises could be supply motivated rather than demand.

I agreed with Paul Krugman’s assessment of this issue which he aired in his recent New York Times Op-Ed (January 31, 2011) – A Cross of Rubber

… food and energy prices – and commodity prices in general – have, of course, been rising lately … What’s that about?

The answer, mainly, is growth in emerging markets. While recovery in advanced nations has been sluggish, developing countries – China in particular – have come roaring back from the 2008 slump. This has created inflation pressures within many of these countries; it has also led to sharply rising global demand for raw materials. Bad weather – especially an unprecedented heat wave in the former Soviet Union, which led to a sharp fall in world wheat production – has also played a role in driving up food prices.

So we have to differentiate the supply constraints (weather, natural disasters) from the demand effects when assessing the rising prices. In Australia, rising food prices are being overwhelmingly driven by natural disasters – first flooding then the cyclone. Elsewhere, as Krugman indicates weather factors have been prominent.

Krugman then considers what the rising prices (especially in China) means for policy in advanced nations:

First of all, inflation in China is China’s problem, not ours. It’s true that right now China’s currency is pegged to the dollar. But that’s China’s choice; if China doesn’t like U.S. monetary policy, it’s free to let its currency rise. Neither China nor anyone else has the right to demand that America strangle its nascent economic recovery just because Chinese exporters want to keep the renminbi undervalued.

What about commodity prices? The Fed normally focuses on “core” inflation, which excludes food and energy, rather than “headline” inflation, because experience shows that while some prices fluctuate widely from month to month, others have a lot of inertia – and it’s the ones with inertia you want to worry about, because once either inflation or deflation gets built into these prices, it’s hard to get rid of … It’s hard to see why the Fed should behave differently this time, with inflation nowhere near as high as it was during the last commodity boom.

I will leave the issue of imported inflation for another blog as it is a topic in its own right.

The point is that national output gaps do matter and tell a government that there are idle resources that can be brought back into productive use with appropriate policies to expand demand. The appropriate policies may include changing the composition of demand as well as the level. If there are price pressures coming through imports then that demand can be squeezed a bit with targetted tax policies. That is also a topic in its own right.

And I also haven’t considered issues relating to bio-fuels, public transport and dietary shifts to provide longer-term solutions to the growing food crisis.But in the writing I have been doing on these topics (for a book I am working on) none of these alternatives imply cutting the real living standards of workers in advanced nations and holding 10 per cent or more American workers in a state of joblessness.

What is essential is that as the world exhausts its finite pool of natural resources governments will have to provide leadership in a reconsideration of our energy use and what constitutes work.

For example, we will have to adopt very broad notions of what is productive work. The private market will never accept this broadening (the way I conceive of it) because there would be no private profit in the activities. For example, I can see advantages in broadening our notion of work to include surfing – whereby the surfer would be a state employee who might offer workshops to school kids on water safety, sand dune and coastal maintenance and physical fitness. The rest of the time they can surf to their heart’s content. I would call that a productive way of accessing the distribution system which would reduce our overall call on natural resources but still provide wages to workers.

A shifting industrial pattern just tells me that there are new opportunities in the domestic economy to take up with the labour that is freed.

Conclusion

Been tied up in Sydney working today so have had little time to write. More next week.

Saturday Quiz

Will be available some time tomorrow as usual unless plenty of people write in and tell me they are bored with it!

That is enough for today!

Bill ~ In yesterday’s blog, you referred back to an older post, “Functional finance and modern monetary theory”. That post in turn started with a mention of the “manufacturing as an economic necessity” argument, which is a main talking point for just about every liberal media talking head in the US, and leads to their support for protectionism. I suspect that what these people are saying is an economic necessity however is really only a political preference, but I’m not sure how to make that argument in MMT terms.

In that functional finance post, you simply dismiss the argument (with a reference to something you call vertical integration), promising to go into the “manufacturing as a necessity” argument in greater detail in a later blog. I’ve checked the archives for a title suggesting a post addressing the topic, but have come up empty. I was wondering whether that blog ever materialized, as I need some help with my arguments on this. Thanks much.

Dear Benedict@Large (at 2011/02/04 at 19:57)

Please see this blog from September 2010 – What you consume or what you produce?.

It was the materialisation of the promise you mentioned.

best wishes

bill

Oxfam say that rising food prices is due to weak harvests, rising oil prices and an increased demand for bio fuels.

One could have thought that we now should have a better understanding how to tackle macro shifts in production patterns than 100 – 150 years ago, that we better understand the process, a much more advanced capacity to observe it and superior organizations skills to not let it hit large parts of the population negative.

Thanks Bill. Look forward to the imported inflation blog when it comes

What a clown Kemp is! Looking at his contention from a much more basic perspective, the world has hundreds of millions of subsistence farmers, huge amounts of capital that could have been used to make these people more productive has been squandered in real estate bubbles, yet the world economy is at full capacity? Does not compute.

China’s Innovative Way of Skinning the United States!

Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. – Albert Einstein

As long as the United States continues to allow China to manipulate the U.S. Dollar and therefore manipulate our trade with ALL our trading partners:

– our balance of trade with ALL our trading partners will be worse than it would otherwise be.

– free trade agreements will work to our disadvantage and we should halt entering into new ones.

Mark Twain is credited with an early use of the cliché “more than one way to skin a cat” in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, as follows: “she was wise, subtle, and knew more than one way to skin a cat, that is, more than one way to get what she wanted”. Thefreedictionary.com defines beggar-thy-neighbor as: an international trade policy of competitive devaluations and increased protective barriers that one country institutes to gain at the expense of its trading partners. Under the guise of fostering ‘indigenous innovation’, the Chinese government has creatively used a non-conventional, subtle version of beggar-thy-neighbor. Its version doesn’t entail the competitive devaluation of its own currency, which would enhance China’s exports and inhibits its trading partners’ exports to China. China’s version perpetrates an over-valuation of the currencies of one or more of its trading partners. This negatively affects all the trade of the pegged trading partner(s), not just trade with China. During the recent period China pegged its currency to the U.S. Dollar, its version of beggar-thy-neighbor was 8 times as damaging to the U.S. economy as what the media refers to as “China keeping it currency undervalued”.

In November 2003, Warren Buffett in his Fortune, Squanderville versus Thriftville article recommended that America adopt a balanced trade model. The fact that advice advocating balance and sustainability, from a sage the caliber of Warren Buffett, could be virtually ignored for over seven years is unfathomable. Until action is taken on Buffett’s or a similar balanced trade model, America will continue to squander time, treasure and talent in pursuit of an illusionary recovery.

When the food price hike was during 2006 to 2008 the case was made to put the “blame” on growth in China and India and its growing middle class indulge in guzzling but according to demand from those countries actually fell by 3 percent over the period; and the International Grain Council stated that global production of wheat had increased during the price spike.

I maybe different now but whenever an economist or ditto proclaimed expert say something one have to expect that its all about excuses for neo-liberals. They are not even remotely trustworthy anymore and whatever they say have to be checked and controlled and controlled again and again.

As with the blame on China for oil price hikes after the record low prices during Clinton. I just happened then to look at OPEC report covering the period from the fall of Soviet empire to 2004. Well China had significantly increased its consumption but the former Soviet had dropped more than that and USA was the place where oil consumption on an per capita basis had increased way more than anywhere else. Otherwise there is a good correlation with the invasion of Iraq and the take off for oil price hike. From one day to another the market, oil experts and so on come aware of China’s oil consumption, peak oil and so on. The oil reserve was much lower during the Clinton period when it even dropped below $10, albeit a “strong” dollar. Oil reserves are calculated related to the oil price, the higher price more is economically to extract.

UK still waiting for that Richardian consumer to fill the gap.

“High-street gloom as consumers stop spending

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/feb/04/shopping-consumers-slump-cars-homes

• People cut spending on everything from homes to DVDs

• Record numbers of people declared insolvent”

“Bank of England chief Mervyn King: standard of living to plunge at fastest rate since 1920s

Households face the most dramatic squeeze in living standards since the 1920s,

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/8282354/Bank-of-England-chief-Mervyn-King-standard-of-living-to-plunge-at-fastest-rate-since-1920s.html

“The squeeze on living standards is the inevitable price to pay for the financial crisis and subsequent rebalancing of the world and UK economies.””

Mervyn King

LOL@import certificates.

Americas main problem is that they make poor quality products that are no match in terms of price or quality with what’s available elsewhere.

Cars in particular are of ridiculously poor quality.

This wasn’t always the case – but it appears to be the norm in recent times.

“UK still waiting for that Richardian consumer to fill the gap.”

According to the Shadow Chancellor, the Ricardian consumer is saving up waiting for the austerity measures to come.

So apparently the Ricardian consumer is confused, which is kind of difficult given that the entire premise of the theory is that they are magically omniscient.

“Ricardian agents as economic Deus ex Machina. Discuss” 🙂

I’d heard that Osborne believed that Ricardo thought that it was so dam cold that he stayed at home and refused to spend in minus degrees. With Osborn and Cameron at the helm it is doubtful if there won’t be anything be icy waters ahead for Ricardo.

Many of these so called economists should put their own name to the theories they throw about rather than tagging them with David Ricardos name.

In much the same way that James Mill and J.R McCullock used J.b Say’s name for their own ideological games it would appear the modern orthodoxy has taken similar liberites with Ricatdo and to a lesser extent Adam Smith.

I’d prefer to think of Ricardo as the founding father of modern economics.

That’s not to say that he didn’t make mistakes.

G’day Bill and all Billy Blog devotees,

Although I think Kemp is totally misguided in much of his explanation for the rise in food and fuel prices, in my view he is correct (perhaps inadvertently) when he says that the global economy is reaching the limits of sustainable output. In fact, if the Global Footprint Network’s measure of humankind’s ecological footprint is any guide, the global economy has well exceeded ecological limits. Humankind’s EF is now 35% larger than the Earth’s biocapacity. The global economy is only able to keep growing because we are still able to relatively safely draw down the planet’s natural capital, a lot of which we use consists of non-renewable resources. We can thank planet Earth’s remarkable resilience for not yet keeling over, but we cannot rely on it forever.

If markets properly reflected the cost of natural resource use and waste generation, the prices of food and fuel would be much higher than they are at present. That’s why policy-makers are terrified of doing the economically responsible thing of internalising spillover costs by introducing depletion/pollution taxes or cap-auction-trade systems.

Kenneth Boulding once pointed out something that seems pretty obvious but is often overlooked – it is the most limiting factor of production that determines ‘sustainable’ productive capacity, whether it be at the national or global level, although there is some leeway with the former if, as a country with an ecological deficit, you can import resources from countries that can maintain suitably large ecological surpluses. This aside, the most limiting factor at present is natural capital. We cannot, therefore, solve the unemployment dilemma independently of the ecological dilemma. We somehow must find a way to achieve full employment when it is clear that we must also reduce our demands on the planet. That won’t be easy. It’s hard enough trying to convince policy-makers to achieve and maintain full employment at a time when continuous growth is still considered plausible.

As I see it, the beauty of the Job Guarantee proposed by Bill and his MMT colleagues, is that it can help achieve full employment regardless of where we stand in relation to ecological limits. If we are still short of ecological limits, the JG can generate the extra demand required to fully employ everyone who wants a job in a non-inflationary manner (i.e., can close the u/e gap). If we have exceeded ecological limits, the JG will lead to cost-push inflation (temporarily) that will reduce real incomes, reduce demand, deflate the private sector, and bring about a non-inflationary outcome that is likely to correspond to a very large ratio of JG workers to conventional workers, although the size of the JG workforce will depend on how efficiently we utilise the incoming resource flow. That is, if we have exceeded ecological limits and we are forced to reduce our demands on natural capital, and this reduces real output to a lower, sustainable level, the JG can ration the lower real GDP in a way that can still result in a non-inflationary, full employment outcome. Some people might not like the second scenario. But if that’s the situation we are in, it will effectively be the result of humankind having failed to do something in the past about population growth and excessive resource consumption.

Extracts from Bill’s post: “Further, in the Emerging and Developing economies there are millions of idle workers and no shortage of resources to deploy to bring these workers into production. For example, South Africa has abundant resources in the form of timber, concrete etc and more than 60 per cent of their population without work, income or adequate housing. Is anyone seriously going to argue that a large-scale public employment program designed to employ people building their own houses (in the first instance) and using locally sourced resources is not possible without driving inflation into an accelerating spiral? ; demand for food might rise and in the case I am using that would be desirable because poverty, joblessness and inadequate food consumption go together.”

I was in South Africa last year and I was interested in the housing projects underway there. Demand for housing is endless as the shanty townships have at least 2 million people in them mostly refugees from other troubled African nations. As I see it the Item most likely to keep the poor poor is energy prices. It looks like the oil producing nations will continue to subsidise energy cost for their people subsidised by the export of Oil at continually increasing prices, which is inflation. How will the poor prosper in a world of real energy inflation? Most of the oil companies are owned by Sovereign Countries who can use oil profits to subsidise energy costs internally.

Paul Zane Pilzer pointed out years ago that the unemployed are a resource. It is up to Governments to use this precious resource via fiscal manipulation. Perhaps they see the unemployed as merely a resource for private profits by keeping them unemployed. Australia’s biggest companies have tricked our politicians into believing we have a skills shortage panicking the Government into all sorts of stupid policies. Like cutting services to pay for flood reconstruction.

Good comments,

We have a fundamental problem. We simply don’t need all the people in the world to produce all the stuff people actually need to live free from poverty.

The question is what do we do with the unrequired surplus of people’s time, yet still ensure they have a share of the resources necessary to live a reasonable life?

Clearly the answer to that can’t be produce endless quantities of unnecessary stuff. We really need to look at systems that can somehow separate ‘work’ from ‘income’.

Neil, what is happening now is that gains from productivity are being hoarded at the top instead of being broadly shared, which is leading to increasing inequality. Historically, rising inequality is unstable and always ends badly. Moreover, as Dee Hock, the founder of VISA International, observed, the corporation was founded to privatize gain and socialize loss, e.g., the British East India Company (chartered as a corporation in 1600). Historically, corporations have successfully pushed to expanded their power and reduced their liability. The result is the corporate state aka “the predator state” (See James K. Galbraith, The Predator State (2008)).

The fact is that through technological innovation, the work ethic is no longer an evolutionary plus and needs to be replaced with something more evolutionary, i.e., produces a greater return on coordination. This can easily be done by sharing the wealth through taxing away economic rent, changing incentives and reorienting major institutions. This would increase nominal aggregate demand, lead to increased productive investment, and foster greater technological innovation. This is not difficult to do with present knowledge. The problem is with cognitive, cultural and institutional inertia.

Rather than great wealth for a few, the world could be enjoying greater prosperity and leisure for all. As democracy spreads and technology results in greater interconnectivity, people are going to figure this out. See Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942).