I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

There is no such thing as a “weak” budget outcome

I imagine a doctor when confronted with a set of symptoms being presented by a patient carefully goes through each one and draws on his/her bank of knowledge, understanding and experience to arrive at an interpretation. A patient that has been sick for some time and is in the early stages of recovery may still exhibit signs of stress and the doctor appreciates that and doesn’t ring any alarm bells. It seems that the same doesn’t apply to my profession. Members of my profession seem to jump on any bandwagon that arrives and which triggers their favourite narratives about excessive government spending and borrowing and all that sort of public misinformation. The most recent example of this came yesterday (December 21, 2010) when the UK Office of National Statistics released the latest data for Public Sector Finances (as at November 2010) which showed that British government spending continues to grow and tax revenue is still lagging. The press reaction and that of my colleagues was expected and as is typically the case way off beam. We can summarise the problem by stating that there is no such thing as a “weak” budget outcome. An economy can be weak but it makes no sense to say a budget outcome is weak unless you have an ideological bias towards some particular outcome.

The UK Guardian (December 21, 2010) said in its article – UK budget deficit reached record £23bn in November – that:

George Osborne received a blow as it emerged that state borrowing soared to the highest on record for a single month despite the government’s austerity measures to rein in the deficit.

News that higher spending on defence, the NHS and contribution to the European Union had left Britain in the red by £23.3bn stunned the City, which had been expecting the early fruits from the chancellor’s spending restraint to cut the deficit from the £17.4bn recorded in November 2009.

So the universal fact is that the bank economists are typically wrong wherever they are.

But why use terms like “soared” and is this “record” meaningful. The answer to the second question is that it makes no sense to compare budget outcomes in terms of their numerical outcomes. Record in relation to what? Some previous outcome? And what was the real economy

The only deficit that matters is the real deficit which we measure in terms of real output gaps, unemployment, underemployment, lower productivity, falling potential output, suppressed real wages and the like. I didn’t read any discussion about “real” deficits yesterday among the commentators reported in the British media.

All the talk was about this record deficit and the rising borrowing.

Coming back to the theme of the blog I note that in this UK Guardian commentary – UK economy may be on track but signals still mixed – (December 21, 2010) the writer says that:

… one set of weak data on public finances does not destroy Osborne’s thesis. But it does illustrate why you should not declare victory on the basis of one set of GDP numbers.

The use of the term “weak” tells me everything. There is no meaningful concept of a “weak” fiscal outcome. The actual numbers that appear on the budget sheet have no meaning in themselves. They always have to be related back to the real economy to aid our interpretation. A rising budget deficit is not good nor bad just as a falling deficit is not good nor bad. It all depends and the only metrics that matter are real aggregates (employment, output, productivity etc).

The UK Guardian was also concerned there was “virtually no improvement on last year” in the budget outcome. Exactly how do we construe an improvement? The mainstream economists who adopt the view that deficits are bad and surpluses are good – which is the sentiment reflected in the press coverage always conclude a falling deficit is an improvement.

However just as the concept of a “weak” budget is awry, the idea of an improving deficit also completely misses the point as to what a deficit is and what it reflects. As I have written previously the deficit is like a barometer of real economic health. But it is an ambiguous indicator. Why?

The budget outcome is the product of two separate but not fully independent components. Overall, the budget balance is the difference between total government revenue and total government outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved.

So:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) + (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

Decisions by the non-government sector to increase its saving will reduce aggregate demand and the multiplier effects will reduce GDP. If nothing else happens to offset that development, then the automatic stabilisers will increase the budget deficit (or reduce the budget surplus).

So in that sense, the causality runs from the non-government sector to the government sector.

However, the government may decide to expand its discretionary spending and/or cut taxes. This will add to aggregate demand and increase GDP. The deficit will increase by some amount less than the discretionary policy expansion because the automatic stabilisers will offset that increase to some extent. But the non-government sector will also enjoy the increased income and this allows them to increase total saving.

So the causality in this situation runs from the government sector to the non-government sector (and feeds back again as the automatic stabilisers go to work).

In general, if the private sector desires to increase its saving, the role of the government is to match that to ensure that the income adjustment will not occur – with the concomitant employment losses etc. In that sense, fiscal policy has to be reacting to private spending and saving decisions (once a private-public mix is politically determined).

Please read my blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that a rising budget deficit might reflect improved real outcomes in the economy just as it might reflect an ailing economy. It all depends which component of the budget is dominant and what is happening in the real economy.

Just mindlessly staring at some budget numbers and computing a change from month to month and then concluding if the deficit has risen that things are worse – just because the number is bigger – gets us nowhere. That is largely what the professional commentary on yesterday’s British data did.

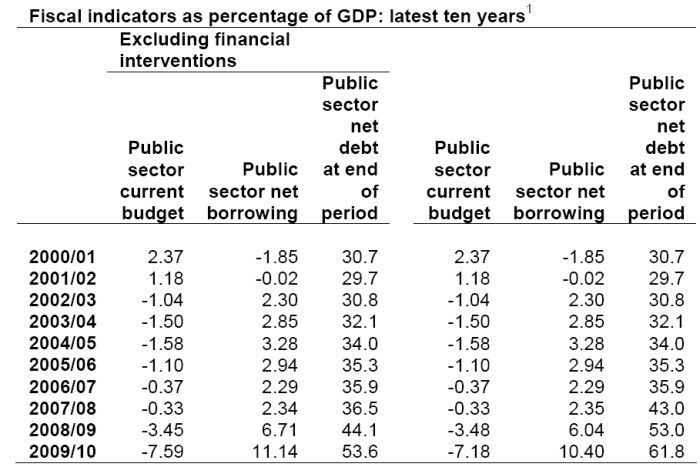

This is the data that got everyone into a spin.

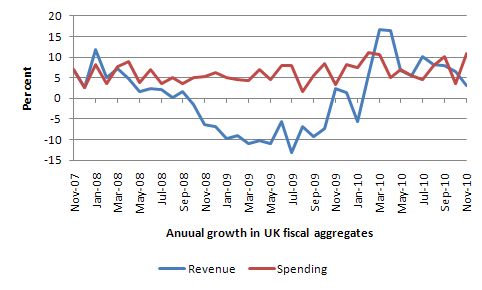

The next graph shows the annual growth in total central government spending and revenue in the UK since November 2007. You can see how significant the downturn in the economy was by the collapse in revenue. But you can also see that spending has hardly blown out in the period of the crisis.

In fact, the British government has been too stingy by far in its reaction to the crisis and that is why unemployment is persisting at high levels and the real output gap is also very high.

The prognosis for the British economy is that it will deteriorate over the next several months as the conservatives cut into spending and push up taxes. The reaction of the Treasury (as reported in the UK Guardian) to yesterday’s data was:

November’s borrowing figures show why the government has had to take decisive action to take Britain out of the financial danger zone …

Presumably that Treasury spokesman is looking to the Chancellor for a promotion because he wouldn’t say such a stupid thing if he wasn’t trying to curry favour with architect of the austerity vandalism.

The borrowing figures indicate that non-government wealth has increased in line with the government spending increase. The bond holders have traded in low or zero earning financial assets for interest-bearing bonds. They will then earn income which will be of benefit to the economy.

Why would we construct that as a negative outcome in the context of an extremely sick economy.

Britain is a sovereign nation (fully in its own currency) and will never enter “the financial danger zone”. This is bond market hype.

We got no better from the “Chief Economist at the British Chambers of Commerce” who said:

These figures are much worse than expected and show a significant increase in the deficit compared with the same month a year ago. Britain’s fiscal position is very serious and it is essential for the government to implement its tough strategy aimed at stabilising our public finances. British business supports these measures and wants to see the government continuing to focus on spending cuts rather than tax rises. But, in order for this policy to be successful the austerity measures must be supplemented by a credible growth strategy so that businesses can drive a lasting recovery.

The only reason the British economy is currently growing is courtesy of the fiscal stimulus (even though it was too small). Where does business think it gets its sale from? Private spending is still way to subdued in the UK for private firms not to suffer when the government starts to seriously cut back.

I also remind readers that the contribution from net exports to aggregate demand in the UK is negative at present and will remain so for the indefinite future.

So why would British business support measures that will damage its bottom line?

The UK Guardian (December 21, 2010) briefed us on Public borrowing: What the economists are saying but only seemed to interview financial market economists. Their responses were revealing.

One said that:

These figures really are a bolt from the blue and will ensure a miserable Christmas for the Treasury … the November figures pretty much wipe out all of the 2010/11 reduction in borrowing in one fell swoop … That it is largely spending which has caused the surge in borrowing is a concern … the strength of spending will provide more fuel for the sceptics who question whether the government can really achieve the scale of public spending cuts that it plans.

I don’t think the budget outcomes were surprising at all given the state of the real economy. Sure enough there has been some growth but there is still a very large output gap.

I am also not the slightest bit concerned that spending has grown

One commentator said that:

The public finances were truly horrible and much worse than expected in November. This is dire news for Chancellor George Osborne to digest over Christmas and is likely to reinforce the government’s belief that there must be no let-up in the fiscal consolidation efforts.

That takes the “cake” for stupid and misleading commentary. Words like horrible have no meaning in this context. They just reflect the ideological bias of the commentator.

A rising deficit which signals a weakening economy (which is probably what is going on at present) should tell the Chancellor that he is on the wrong track. Exactly the opposite to what this commentator thinks is the message.

I wonder if he would be so comfortable if we said that his job would vanish if unemployment rose in the face of Osborne’s austerity cuts. I wonder if his message wouldn’t change somewhat.

The rescue packages have helped the financial sector in the US (and elsewhere) and feathered the pay packets and job security of these sorts of commentators. It is easy for them to propose cuts for everyone else but it would have actually been better if the government had have let most of these banks and speculators go broke and instead concentrate their stimulus measures at the bottom end of the labour market.

The same commentator also said:

A further serious problem for the government is that interest payments are increasing markedly. Indeed, the breakdown of central government expenditure shows interest payments were up to £4.5bn in November from £3.0bn a year earlier. The government is highlighting this as a key reason to why the public finances must be improved as quickly as possible.

Given that the British government is sovereign and not revenue constrained and given there is excess capacity in the economy why are these interest payments a “further serious problem”. They provide the non-government sector with income and there is zero opportunity cost to the government.

Why is interest income from the government bad and dividends from a private firm good? I can only ever interpret that sort of claptrap through as ideological statements which reflect the distaste of the commentator for public life and public service.

Another “capital markets” economist said that:

If borrowing continues to increase in this manner in the next few months, the government will be in danger of overshooting the £149bn deficit projection set out by the OBR for the current financial year. And while the higher VAT rate from January should help to boost revenues, a sharp slowdown in consumer spending will dampen its near-term effect on revenues.

Yes and yes.

The projections are nonsensical and the government cannot control the budget outcome anyway. It is always better for the government to concentrate on ensuring there is enough spending in the economy to support employment growth and the desire to save by the non-government sector.

Further, the fiscal austerity will be counter-productive if the government’s aim is to reduce the deficit. You need economic growth to achieve that outcome and that will be better achieved via increasing the discretionary component of the budget.

What really matters …

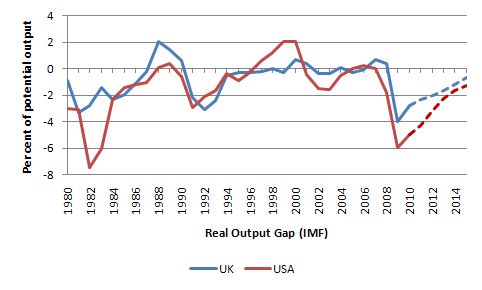

To see these results in perspective you need to look at the real economy. The following graph shows the real GDP output gap as a percentage of potential output as measured by the IMF in its World Economic Outlook database as at October 2010. The dotted segments are the IMF forecasts to 2015.

As at October 2010, the UK output gap was as bad as it was in the second year of the 1982 recession. In that episode it took a further five years before the economy reached potential again (according to this measure). For various reasons, the gaps are likely to be very conservative (that is, understate the true gaps). So you best consider them in relative terms.

The point is that the UK economy has improved a little as the spending boost from the deficit has been working its way through the system. But even with the improvement there is still a huge shortfall of capacity that is being underutilised. With fiscal austerity about to bite the economy will go into reverse.

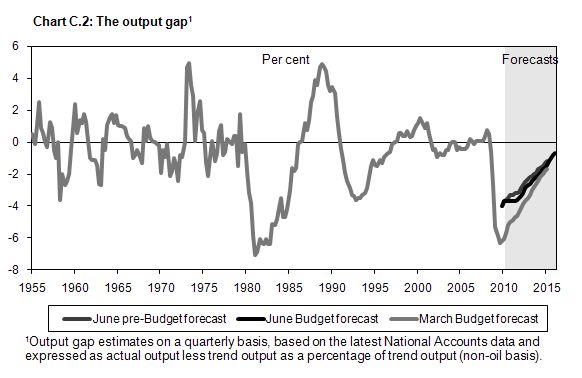

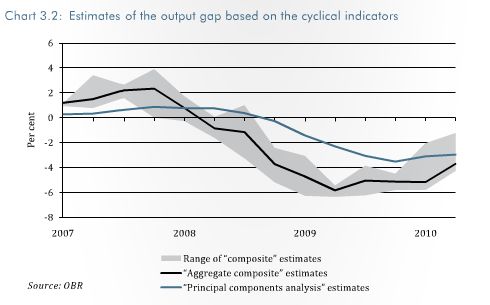

The next graph is an alternative depiction of the UK Output Gap produced by the Office of Budget Responsibility and used by the British Treasury in framing the current Budget which was released in June 2010.

The graph shows the percentage deviation in actual real GDP from trend (expressed in terms of trend output). This is also likely to understate the extent of the real output gap given the methodology that the Office of Budget Responsibility uses to estimate trend real output.

You can read about the issues involved in the production of an output gap measure in the Economic and Fiscal Outlook November 2010 produced by the Office of Budget Responsibility – look for pages 129-132.

They detail various measures that have been produced using different methodologies. Their best guess is an output gap around 4 per cent which is larger than that produced by the IMF.

Whichever way you want to look at it the British economy is still a long way from reaching its capacity and in that sense still requires fiscal support.

I could have also produced several perspectives of the idle labour story in the UK at present. While unemployment and underemployment have an important human dimension which should never be ignored, from an economic perspective they tell us the same sort of story as the output gap. Foregone incomes, foregone output – never to be regained – wasted daily which would be reduced if aggregate demand was stronger.

So I see yesterday’s fiscal outcomes as heading in the right direction relative to what the real economy (the patient) is telling me. Now is the time to expand government net spending in the British economy.

The consternation about the rising debt in the UK is also amusing and demonstrated that the commentators have not really understood what public debt is and the voluntary nature of its issuance.

Please read my blogs – Debt is not debt and On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

To repeat: The UK economy requires further fiscal support and that indicates a rising budget deficit. In that context, the figures for November released yesterday are heading in the right direction.

Whatever, using terms such as “weak”, “horrible”, etc to describe some budget numbers is as stupid as describing a logarithm as yellow!

That is enough for today!

Sorry to ask this here, but I appeal to an MMT’er to explain to a hapless fool (or show me a blog) to help me understand a bit better the internal effects of stimulus financing. Bear with me on this.

For example, during the GFC the Govt decides to secretly stimulate the economy by crediting Raymond D’s bank account with a billion dollars which in turn I agree to spend as fast as I can at various retail outlets.

Now considering I don’t tell anyone and dutifully shop till I drop how would anyone know that the money supply has expanded? I expect this would be inflationary as I have taken out of the system more commodities than I would previously have been capable of but is the recording of the money supply an honourary duty of the government to reveal or could they sneakily create a huge stimulus and then perhaps equally secretly reduce their reserves when the economy responds without anyone being the wiser?

Perhaps one of you can help me with something I’m struggling with.

“Given that the British government is sovereign and not revenue constrained and given there is excess capacity in the economy why are these interest payments a “further serious problem”. They provide the non-government sector with income and there is zero opportunity cost to the government.

Why is interest income from the government bad and dividends from a private firm good? I can only ever interpret that sort of claptrap through as ideological statements which reflect the distaste of the commentator for public life and public service.”

I understand the sentiments here, but isn’t it the case that the interest payments are being made largely on bonds and they are paying an interest rate higher than the Bank Base Rate (0.5%), and that higher interest rate means that the currency exchange rate is higher than it otherwise would be – favouring imports over exports.

If the UK suddenly stopped issuing bonds and paying interest (so that more and more money only received the Bank Rate), but moved that government spending elsewhere (so there is no difference in the net-injections into the non-government sector) would the exchange rate be expected to stay the same?

“I expect this would be inflationary as I have taken out of the system more commodities than I would previously have been capable of ”

That depends whether there was a billion dollars worth of stuff that nobody else wanted. If there was, then it would not be inflationary – instead you would have prevented a price collapse. Not only that but your spending would have signalled that there was still demand in the market to suppliers who would have at least maintained production if not increased it.

One of the main problems with mainstream economics appears to be that they don’t believe there is ever any slack in the system. Perhaps their religion forbids it.

Businesses would know that their sales were up, profits up, sales and profits taxes up, no doubt some imports up, less job losses, less welfare payments, in short demand and incomes would be higher as there’s spare capacity to respond without much/any price increase. MV equates to PT so Ms up, V depends on if you save more or less than the mean, Transactions up, Prices unlikely to change much. Why bother draining reserves? Money supply is hard to measure but all the other economic factors I’ve mentioned are easier…the real economy is on a better income/demand/growth track…’rah!

Ray,

I am not an economist but I think that I can suggest an answer based on my understanding of impulse/step responses of low-pass digital filters.

If what I’ve written is unclear please have a look at link_https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=6949

If you spend extra 1 bln on goods and services over a certain period of time (let’s say 6 months) this will temporarily increase the flow of goods and services. (I am talking about a one-off injection not a permanent increase in expenditures).

Retailers will see that their sales are going up. They will order goods from the manufacturers of final goods who in turn will order more intermediate goods. All these firms will generate additional income for households on top of the usual flows. Assuming unused productive capacities, commodity prices and wage level (labour price) may not increase and there will be no input to inflation. Otherwise why would you stimulate the economy?

Now let’s assume that people only consume and save with the marginal propensity 20% (there is no investment financed directly from profits and we ignore taxes and import). Let’s assume that the average production/consumption cycle also takes 6 months and won’t change as a result of the injection (we can refer to money velocity here). The additional injection of money will lead to an increase in wages/dividends by 1bln over the first cycle (over the unbiased GDP), 0.8 over the second cycle (as 20% would be saved), 0.64 over the third cycle etc… The influence of the stimulus will disappear over time as we just injected money once, not increased the flow permanently.

However if increased spending affects the investment decisions (this is the only place where I refer to “expectations” or possibly “rational” human behaviour) – the influence of the one-off stimulus may be persistent.

In our case information is not carried by the market pricing channel but by the increased volume which leads to increased profits. This is also a market signal.

Let’s assume that buoyed by (temporarily – but they don’t know about that) increased sales – by demand for final/intermediate goods, business owners/managers increase their investment (flow) by $20mln/year (this process is described by the accelerator theory). This is the only non-linear element of the circuit as all the other components are linear and all the changes to flows (not stocks) caused by an one-off stimulus are reversible. Since investment spending generates its own savings flow which has to match the increase in the investment, the GDP will increase by 5*20mln/year that is by 100mln/year (5 is 1/0.2 as the marginal propensity to save is assumed to be 0.2 – this is described by the investment multiplier theory). Over time the investment decisions may be revised downwards when the influence of the original injection weans off however there will always be some residual persistent increase in the GDP (hysteresis) as the increase in investment has already brought about its own increased flow of consumption (and savings).

Neil, Re your concern about the exchange rate, I don’t think this is important. The exchange rate is an example of a so called “intermediate objective” (frowned on in economics).

The more fundamental question is whether government borrowing (i.e. bonds) are a good idea: in particular, would they be a good idea in a closed economy (i.e. where there is no foreign trade). Or to use the wording of your last para would it be a good idea “If the UK suddenly stopped issuing bonds and paying interest . . . but moved that government spending elsewhere”?

My answer to the latter question is “yes”. That is because I favour the Abba Lerner policy of just altering government net spending, and not using bonds or interest rates to influence aggregate demand.

On that point discovered from Warren Mosler’s site this morning that Congressman Dennis Kucinich is pushing a bill that would abolish government borrowing. I support that, though some of his ideas are nonsense.

Ralph, I think it is important to note that Dr. Lerner later amended his position on functional finance to include an explicit inflation targeting mechanism besides just increasing taxes or decreasing government spending. From: “”Functional Finance, New Classical Economics and Great Great Grandsons,” by David Colander:

“To integrate the necessity of dealing with the institutional problem of sellers’ inflation by changing institutions rather than accepting whatever unemployment was required to stop inflation, Lerner and I arrived at a modification of the rules of functional finance. Specifically, we added a fourth rule: ‘The government must establish policies which stabilize the price level and coordinate both the money supply rule and the aggregate total spending rule with this stable price level at the unemployment level it prefers.’ With this fourth rule the rules of functional finance can once again be relevant to modern economic problems.”

The specific policy to “stabilize the price level and coordinate both the money supply rule and the aggregate total spending rule with this stable price level at the unemployment level it prefers,” Dr. Colander formulated and Dr. Lerner approved of was called the “Market Anti-Inflation Plan (MAP).” I have talked about that plan several times here on Billy Blog and hope that Professor Mitchell will address the MAP proposal when he does his post on supply-side inflation.

Forgot to include a link to the “Great Great Grandsons,” paper:

http://community.middlebury.edu/~colander/articles/Functional%20Finance,%20New%20Classical%20Economics%20and%20Great%20Great%20Grandsons.pdf

Also, if you’re interested in learning more about the MAP, a good place to start is Dr. Colander’s “A Real Theory of Inflation and Anti-Inflation Plans.” Specific discussion of how the MAP would function starts on page six of the PDF:

http://community.middlebury.edu/~colander/articles/real_theory_inflation.pdf

thanks Adam, that makes sense but the part I was most interested in was about the money supply and changed scarcity of money.

We are talking about an undisclosed increase in the money supply crediting my bank account. From what you have mentioned, the ‘economy’ sort of finds out by the effect on consumption but what processes are in place to prevent a Government simply printing money into the system without anyone knowing?

What if they credited my bank account by a trillion dollars which I spent? When does the penny drop within the system that something is amiss? Alternatively, what if the money printing company unlawfully prints an extra trillion in hundred dollar notes and gives it to me? Where are the checks and balances in place that this doesn’t happen and how would anyone ever find out (from an economics rather than accounting point of view)?

When purchasing power exceeds an economies’ ability to produce, the availability of goods and services will decline and prices will rise. That would be a sign that something is amiss.

Meanwhile there is lots of money sitting idle in the private sector. Instead of being spent on goods and services it is ‘invested’ in the Wall Street casino. Yet another sign that something is amiss.

http://kucinich.house.gov/UploadedFiles/NEED_ACT.pdf

Dennis Kucinich, House of Representatives, U.S.A., has proposed legislation to create a full employment economy. This bill will likely be reintroduced in the next session of the U.S. Congress. This bill is a radical departure from the system that failed the U.S. and world economies.

Please comment on the bill’s efficacy. Apart from the difficulties in passing it, will its ideas provide a basis for popular support based on a real possibility of meeting its stated goals? I’m looking for comment from people who are in agreement with the need for substantial changes, such as populate this discussion group.

Ray,

“what processes are in place to prevent a Government simply printing money into the system without anyone knowing?”

This is a very good question – about the Government accountability in either democratic or oligarchic systems.

… what processes are in place to prevent a Government invading a Middle-Eastern country rich in oil? What processes are in place to prevent a Government allowing for another massive speculative bubble forming in the economy because of reckless money lending and securitization?

I have to admit that I am not sure whether I know an answer.

Ray – I’ve wondered the same. Surely in practice this billion couldn’t hide, given the BoE and ONS bottom-up reporting regimes in place, which – critically – permit a reconciliation of net gilt issuance to the public sector net cash requirement etc.

Separate question is of course why this reconcilable regime exists – and whether a govt could try and sneak in a billion in cahoots with these two organisations.

Whilst the effects might be apparent (more so if there’s no output gap), I’m not clear how anyone could ever find out what had happened!

MMTP

MMTP,

I suspect it comes down to credibility. If it is Zimbabwe then this practice has probably happened a million times and the results are apparent however in the more accountable countries it is assummed this sort of devilry cannot occur.

I would think an awful lot of retail stimulus could be easily created with a few well placed bank account credits considering multiplier effects throughout the economy and have often wondered just what prevents this happening.

As Adam says, if a country can bring itself to invading others, engaging in covert assassinations et al, then surely secretly self-stimulating 😉 is going to be a most minor evil.

Ray,

Zimbabwee’s problems were a result of supply-shock factors, as are most hyperinflations (Chinese hyperinflation, Weimar etc – often after a radical economic restructing following a war). With Zimbabwee, think about it: output collapses (and output potential as a result of land distribution problems and draconian anti-white laws), which then causes prices to increase (without even needing to “print money” per se), which then further causes the money supply and velocity to increase as more and more people seek to claim distributional claim on finite resources that are available, if anything. A vicious cycle between the two emerge. The question is why “print” money implies printing money is the inital casual problem. It isn’t. It is an effect shock that exacerbates the supply shock. You could “print” money in the U.S. but if output potential is high, it won’t do very much. There are alot of resources to go around economy-wide. The banks effectively “accomodate” the endogenous demand for money, so as things spiral out of control higher “currency” emerges (from a 100 dollar note, to 1 000 000 000 ). Of course, the government should simply say “NO” and freeze the currency, as happened with Weimar Germany.

Hyperinflation is far more complex than “printing money”.

Has the US had a domestic war which has occupied it’s entire economy? NO! Is the U.S. productive capacity faltering or capacity utilisation uncapable of increasing? NO! Btw, if “Raymond D’s” account were credited, how do we know Raymond won’t first use the money to pay off hids $700 000 mortgage? And if he spends, how do you know those businesses won’t simply pay off their business and private debt?

It is an effect shock: sorry, meant to read : “It is an after shock that is a consquence, and then exacerbates the supply shock”.

Spadj says:

Thursday, December 23, 2010 at 11:13

“if “Raymond D’s” account were credited, how do we know Raymond won’t first use the money to pay off hids $700 000 mortgage? And if he spends, how do you know those businesses won’t simply pay off their business and private debt?”

I guess if that occurred then it frees up capital that would otherwise have been allocated in the future for such purposes.

I think I see now where Bill is going in saying that there ought be fiscal stimulus up until the point where excess capacity has been utilised which in turn should mean unemployment is cyclically low.

One question however; it seems in the modern world economy that there is always plenty of idle capacity rather than the other way around therefore one could argue for stimulus in perpetuity thus resulting in continued government deficits. Perhaps just a handful of countries (China) could reasonably be expected to plan for budget surpluses to aid monetary policy in dampening demand for production and redirecting money from investment to savings.

Have I gotten this right?

Dear Bill,

For anyone interested a chart of the sectoral financial balances for the US: http://pragcap.com/sectoral-balances-and-the-united-states

Cheers…

jrbarch

“I think I see now where Bill is going in saying that there ought be fiscal stimulus up until the point where excess capacity has been utilised which in turn should mean unemployment is cyclically low”.

Ray, I’m glad to hear it.

Via Naked Capitalism I found this article interesting:

http://www.qfinance.com/macroeconomic-issues-viewpoints/understanding-and-forecasting-the-credit-cyclewhy-the-mainstream-paradigm-in-economics-and-finance-collapsed?full#s4

It made me think about the whole concept of the “money supply”, which I am coming to believe is about as useful as that of the “money multiplier”.

When you consider that we have a public fiat money system linked with a private credit money system – thinking about what happens if I win the global lottery and spend $1 trillion, while thought provoking, is somewhat off point. (You need to ask, where was that $1 trillion before I won it – a topic for a comment at a later date).

The article makes an interesting political economy assertion as to why Japan has stagnated despite significant government spending. Although the government spends, the private sector has contracted credit. You get a political standoff, a stagnation – exactly what has been happening in Japan. As the article says, “Fiscal policy on its own does not create credit.” Very significant point.

I was thinking this is an interesting way to look at hyperinflation episodes, such as Zimbabwe. From a real economic perspective, certainly the lack of economic capacity raises real prices. But from a monetary dimension, this is reflected in a collapse of credit, so the government must step in to issue more base money – but this can only be a political stopgap, because once that happens, credit will never return until there is a new monetary regime.

The other thing I was thinking is that there really is no “money supply” in the way in which it is often thought. This goes to Bill’s quiz question last week about base money adjusting to changes in the money supply. Of course, the private credit money “supply” is leveraged off the base. A contraction of base money will constrict credit creation, but the converse is anything but true (as we know from the “pushing on a string” and liquidity trap thesis).

When you consider the private credit money system, the money supply does not steadily increase or decrease, it is completely dynamic and volatile. The classical methods of monetary expansion (government spending, taxes, bonds) doesn’t really tell us what is going to occur in the credit world (influences, but does not determine), but the credit money world is where the action is (in terms of driving real economic output).

Another thinking point from this article is the idea that “There Is No Such Thing As A Bank Loan” – the bank doesn’t really loan (transfer control) of anything – issuing credit is fundamentally different from loaning money. Need to consider that a bit more to understand the implications.

It is not enough to recommend increased government spending – there has to be a corresponding set of regulations over the private credit money system. Again, the article makes a simple regulatory principle – distinguishing credit creation for GDP spending vs. non-GDP spending. Very elegant.

pebird,

I think Richard Werner’s point is that he wants the government to step in and expand the horizontal credit creation channel normally the domain of the private sector instead of waiting until the private sector becomes comfortable to start taking on new loans. A permanent credit expansion through pubic and private waves.

There was a FT article where Bill quoted some financial analyst that said it was the primary credit creation that was important and not the derivate of the initial credit expansion. He said he would come back to it but probably forgot about it.

pebird,

I think Richard Werner’s point is that he wants the government to step in and expand the horizontal credit creation channel normally the domain of the private sector instead of waiting until the private sector becomes comfortable to start taking on new loans. A permanent credit expansion through public and private waves.

There was a FT article where Bill quoted some financial analyst that said it was the primary credit creation that was important and not the derivative of the initial credit expansion. He said he would come back to it but probably forgot about it.