I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Public infrastructure does not have to earn commercial returns

The Australian government released the business plan for NBN Co today which outlines the “cost-benefit” case for creating a monopoly wholesaler of fibre-based broadband services in Australia and investing some $A27 billion in public funds to create the network. The business case has been the focus of much political debate over the last year or so and as usual most of the debate has been conducted on a spurious basis – that is, the assumption is that the budget outlays proposed represent a “cost” to government and that by committing funds to this project the government is less able to “afford” other projects – presumably because there is some “budget balance outcome” that it cannot deviate from. Neither proposition is valid. While this blog has an Australian flavour the general economic principles apply to all national governments contemplating large-scale public infrastructure developments. The general point is that the provision of public infrastructure does not have to earn commercial returns.

The Government hasn’t helped its case by continually making statements that it is committed to getting the budget back into surplus as soon as possible without reference to what the other sectors (external and private domestic) might be intending. The budget outcome is not determined by government alone and by artificially imposing a constraint on itself it may well guarantee that the budget moves in the opposite direction to that intended.

By imposing these nonsensical fiscal rules on itself independent of the actual trajectory that private spending may take the Government is taking a high risk strategy. If private spending is weaker – and we have already seen that the exchange rate appreciation is reducing the capacity of the Government to achieve these fiscal targets – then the overall aspiration for a budget surplus may be impossible to realise.

It is far better for governments to acknowledge that the budget outcome is driven by a combination of discretionary government spending and taxation decisions in addition to the spending decisions taken by the non-government sector (including the state of net exports, household saving and private gross fixed capital formation).

Further, the decision to invest in a national broadband network (NBN) should not be taken on “financial” grounds. Rather the social costs and returns should be considered along with the availability of the real resources (and their competing uses) necessary to construct the infrastructure. I previously wrote about the NBN proposal in this blog – Free public broadband is required.

Anyway, I tried to access the 160-page business plan from NBN Co’s home page and got this message:

Not a good start I thought for a national broadband provider!

I finally was able to access the document at this – address – the PDF is 3 mgbs.

The document is very interesting in many ways not the least being the engineering detail involved. I found all those aspects fascinating. But the economics of the case is less than compelling and exposes the whole plan to its neo-liberal bias.

The goals of the NBN include:

- The network should be designed to provide an open access, wholesale only, national network.

- NBN Co should offer uniform national wholesale pricing over the network.

- The expected rate of return should, at a minimum, be in excess of current public debt rates.

So the first two goals (among others) are fine and reflect the fact that Australia has had an very poor record of broadband provision since the privatisation of Telstra (which effectively represented a natural monopoly in copper wire telecommunications).

The first two goals also recognise that Australia is a vast land mass with a highly dense population hugging the coastline and a much sparser population living inland but our national psyche says that all citizens should enjoy equal access to public infrastructure such as telecommunications, post and other essential services.

In practice, it doesn’t work out that way but the principle is ingrained in our public policy debates and large cross-subsidies to the regional and remote areas have long been the norm – particularly in the provision of telecommunication services. For years, the high volume long distance services between the capital cities has been milked (higher prices) to provide the resources to ensure that telephony is available to the low-volume areas in the regions.

I have long been a critic of the hidden cross-subsidy approach that successive governments adopted as part of their charter to ensure that public or partly-public owned enterprises fulfull what have been called community service objectives (CSOs). My argument has always been that if there are CSOs to be delivered then there should be an explicit recognition that real resources are being so diverted and that some indication of the extent of this “real” diversion should be publicly available.

Then the citizens can decide via the ballot box whether they want to collectively use these real services in this way with the full knowledge of what is involved.

However, the final goal listed above tells us that the neo-liberals are well and truly running this initiative and that this ideological bias is probably distorting the investment decision-making framework being used by the Government.

The NBN Co document (page 12) recognises “the need to cross-subsidise non-commercially viable market segments” and that “NBN Co will not be able to compete effectively with cherry pickers, who focus on commercially attractive areas only”. So legislative or economic (levies) protection will be required to prevent the cherry pickers from rendering the NBN uncompetitive.

On page 13, the plan says:

NBN Co has reflected the Government’s decision that the Company should implement an internal cross-subsidy to provide uniform national wholesale pricing over the network, from a PoI to a premises.

PoI = point of interconnection to the wholesale network.

On Page 100, the “pricing principles” are outlined. I found most of this discussion irrelevant although the comparisons between the proposed services (speeds, technologies) and existing capacity was interesting. The message is clear – we are being so poorly served at present. But why should NBN Co care about pricing in relation to existing commercial services?

The press conference today (when the Prime Minister released the report) was dominated by discussions of pricing. There is no reason why the NBN Co should seek a commercial return at all. This is a public good that is being provided.

The whole argument appears to be based on the Prime Minister’s claim that the “taxpayers will get all their funds back with interest”. The reality is that the taxpayer will not be putting any funds into the project. Please read my blog – Taxpayers do not fund anything.

By forcing NBN Co to deliver a near commercial rate of return, the Government is ensuring that the retail prices will be higher than is necessary for such an elemental service.

On Page 104, the NBN Co summarises the internal rate of return (IRR) that is expects.

The response from News Limited via the national daily – The Australian (December 20, 2010) was that – NBN return to be lower than in a commercial world, business plan shows – to which I said so what?

The Australian article said:

THE National Broadband Network will deliver an internal rate of return of 7 per cent … NBN Co boss Mike Quigley said the internal rate of return for the business case was lower than might be expected in a commercial business plan … It will also be profitable, meaning taxpayers’ investment in the NBN “will be returned with interest”, while uniform wholesale prices will also be achieved.

There are several different cost-benefit indicators that can be used when determining capital budgeting and assessing different uses of such capital.

The Internal Rate of Return is one such measure and is often referred to as the “the discounted cash flow rate of return (DCFROR) or simply the rate of return (ROR)”.

For those not familiar with discounted cash flow analysis, we recognise that a large-scale project involves revenue and outlays over multi-periods and to assess the return on such a project over some “lifetime” we have to devise a way to compare these temporal flows on a consistent basis.

The Present Value concept recognises that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow because it can be invested and interest gained. So revenue or costs in future periods cannot be readily compared with revenue and costs now.

To overcome this temporal issue, we define a present value by “discounting” future cash flows to take into account the “time value of money” and “investment risk”. We thus use some interest rate (discount rate) to bring all future revenue/outlays back to a present day value. You can look up formulas to see how this is done if you are interested.

The net present value (NPV) is just the sum of the revenues (in present value terms) minus the sum of the outlays (also in present value terms). The NPV indicates the value on a long-term project and if the NPV > 0 then the project adds value to the firm.

There is a huge debate about the short-comings of NPVs as a guide to capital expenditure. I will leave it to your curiosity to pursue the literature further should you be interested.

In the context of this blog, one such issue is that NPVs do not tell you the profit in percentage terms of investing in a specific project. They merely indicate the value of an investment. They do not provide information about the efficiency or yield of the investment. In this context, the use of the internal rate of return is indicated in the literature.

Imagine you want to know the break-even discount rate where the present value of all outlays equals the present value of all revenue. That discount rate is the IRR. The higher the IRR, the more desirable the project.

The finance literature claims that a firm should undertake all projects where the IRR > cost of capital. It is for this reason that the NBN Co’s business plan makes it clear the the IRR (7 per cent) exceeds the long-term bond rate (the yield associated with the issuance of long-term public bonds). But in the biased parlance of the government, the long-term bond rate is what they think is the “cost of raising funds”.

The literature on discounted cash flow analysis is full of warnings about the pitfalls in using IRR measures to guide capital budgeting. One major qualification relates to interim cash flows that a project might or might not deliver over the life of the project. For example, see this this article.

However, the concept – the cost of raising funds – has no application to a sovereign government which is not revenue-constrained.

To make headway we need to take the National Broadband Plan out of the “free market rhetoric” and see it as an essential public good that is best constructed as a “natural monopoly” by the national government which faces no financing constraints. Then you have a different perspective altogether and most of the debate that is going on at present falls away as irrelevant and its ideological basis becomes immediately obvious.

First, why should the provision of the optic fibre network be evaluated in commercial value (read: what will make profits for a private corporation)? In saying that I am not considering so-called value-adding services that might use the network. Just consider the network itself – the optic fibre into our houses.

Why should that not be seen as essential public infrastructure? In that context, it is immediately obvious that it becomes the legitimate responsibility of the Federal government to provide it to advance public purpose? Clearly if we ignore the neo-liberal biases that have derailed the global economy after years of eliminating public provision of essential infrastructure the benefits of having a universal and single infrastructure based on best-practice are obvious.

Second, what does it actually cost? There is very little discussion of this in the NBN Co’s business plan. How many workers are going to be employed? What skills mixes will be required? What training is NBN going to provide to ensure the huge pool of idle labour currently available will benefit from the infrastructure development? And questions like this that relate to the real resource implications of the project …

The only reference to employment appears on Page 153 of the Plan, where we read that:

Under the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, these principles support the creation of quality jobs by ensuring that NBN Co procurement decisions are consistent with the Fair Work Act and its aims, including promoting fair, cooperative and productive workplaces.

Okay, that is a good principle – the NBN is not going to undermine employment conditions.

Answer: there is nothing in the Business Plan about these issues. So the rate of return analysis is in my view irrelevant. I want to know what real resources are going to be deployed and what alternative uses these resources may have been occupied in. Then we can consider the true costs against the social benefits forthcoming.

However, the general principle is that if the real goods and services that are required to construct it are available then the Federal government will be able to purchase them using deficit spending. No debt issuance is required. The only reason that debt might be issued coincidently with the spending incurred to construct the network is if the Federal government considered there was too much liquidity in the private economy which was thwarting its overall economic management (most notably monetary policy).

It is highly likely that the results of the current economic downturn will be a protracted period of under-utilised capacity, particularly labour and so net government spending (rising deficits) will be extremely beneficial to the economy.

So arguments about how the government will pay for the broadband network (and the “costs”) are largely irrelevant. It will pay for it like it pays for anything else by signing cheques and crediting private bank accounts. Then it will monitor the general state of the economy and it might increase taxes or issue bonds if they want private purchasing power to be less.

Of-course, it might also decrease taxes and buy back bonds if it considers more private purchasing power is required. You can see the point. These liquidity management issues are not related in any causal way with the decision by the Federal government to net spend in the AUD to build the broadband network.

Further, once we clear the neo-liberal baggage surrounding “financing issues” then we can further dismiss the arguments about the broadband network being doomed to fail because the high access fees that will be necessary to recoup commercial returns will choke off household demand. These arguments are just nonsensical and rely on us believing that the only value that matters are commercial (privatised) returns.

Why are we being manipulated by all and sundry into constructing this infrastructure solely in terms of a market-based (privatised) commercial project?

In 2003 I wrote this article – Divisions over public debt – for the self-styled progressive organisation the Evatt Foundation, which was set up to honour H.V. Evatt a prominent Labor politician during the 1940s and 1950s and which has been largely funded by state and federal labor governments.

The article noted that

The recent Commonwealth Treasury Debt Management Review highlights the damaging divide among ‘progressive economists’ in Australia when it comes to macroeconomic analysis. This fracture is greater than the things that bind us and helps the neo-liberal orthodoxy to defend their appalling economic record.

This was in reference to a public enquiry set up by the Federal Government in 2002 to address concerns expressed by the Sydney Futures Exchange and other beneficiaries of corporate welfare in the form of public debt. The conservative government had been running consistent budget surpluses and retiring public debt to the point that the bond markets were became too thin and this threatened the welfare received by the bond traders in the form of a ready supply of risk-free annuities that the government bonds provided.

At the time, two submissions were made to the Treasury Review by progressive economists. The Evatt Foundation submission, based on papers by Tony Aspromourgos and Frank Stilwell, was the polar opposite to that submitted by the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE) (written by myself and Warren Mosler).

The other review submissions were largely self-serving pleadings for continued government assistance from the major players in the Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) market. Why would the Evatt Submission reach the same conclusion as the financial markets?

I noted that the:

The equations in the Evatt Submission are derived from the GBC model. Stilwell also operates within this framework, saying that “Governments can finance their expenditure either by taxes or by borrowing … [and with political constraints on taxation] … reduced government borrowing means lower capital expenditure. So the deterioration in public infrastructure – in the quality of ‘public goods’ in general – is a direct consequence of the commitment to debt reduction”.

Immediately, the argument then becomes one of ‘why isn’t there more debt issuance’ as opposed to ‘why aren’t there budget deficits’. The decline in the quantity (quality) of public goods is a direct consequence of inadequate levels of government spending and has nothing at all to do with the extent of CGS issuance. To link the two essentially independent functions is to constrain the macroeconomic analysis within an orthodox paradigm.

The reality is that the Australian government like all sovereign governments does not have to finance its spending either by raising taxation revenue or borrowing. A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.

This has to become a fundamental postulate of progressive economists or else they will always be locked into the nonsensical mainstream logic that is derived when you interpret the government budget constraint (GBC) as representing an a priori financial constraint. The only sensible (and boring) interpretation of the GBC is that is is an ex post accounting statement of the stock-flow relationships that pertain to government spending, taxation and debt-issuance.

The GBC never tells us that there is a binding financial constraint on government spending. The fact that governments issue debt and continually talk about taxpayers’ funds just reflects their obedience to the dominant neo-liberal paradigm rather than saying anything intrinsic about the operational possibilities of the monetary system it operates.

The ‘financing’ trichotomy in the GBC (taxes, printing money, borrowing) is not a robust description of the way in which government spending and financial markets work. The government spends by crediting an account at a Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) member bank.

This process cannot be revenue constrained (government cheques don’t bounce). Governments don’t spend by ‘printing money’. Taxation consists of debiting an account at a RBA member bank. While the funds debited are ‘accounted for’ they don’t actually ‘go anywhere’ nor ‘accumulate’.

Please read my blogs – Taxpayers do not fund anything and On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose – for more discussion on this point.

Stillwell also said that:

Of course, government borrowing involves a cost – the interest payments on government bonds, for example … But whether the interest constitutes a ‘burden’ depends upon how it compares with the social benefits arising from the government spending. As in the case of the carpenter’s personal debt, the interest payments are not a net burden if the future income-generating capacity is enhanced.

This is the old Keynesian defence of the unnecessary and is almost apologetic in nature. It is a sort of ‘well if it is good for the household then it must be good for government’. In doing so we are left with the false neo-liberal analogy between the private agent (user of the currency) and the government (issuer of the currency).

The factors that lead a private investor to borrow are varied, but all of them are irrelevant for the government spending decision. If there is a social ‘rate of return’ for a particular item of government spending then it will accrue whether there is debt issued or not. To say that some public debt is wise and some is unwise, as the Evatt Submission does, is to fundamentally misconstrue the purpose of the debt issuance – which is to drain excess liquidity to allow monetary policy to work.

I concluded that article by saying that once we accept that government spending is not financially constrained and appreciate that public debt issuance is about monetary policy we can see that progressive talk about an optimal debt ratio is both irrelevant to achieving full employment and damaging to the progressive cause.

An economy can easily sustain zero public debt issuance without aberrant economic consequences. The important point that must bind progressive economists is that the government must net spend to sustain aggregate demand levels consistent with a full employment objective.

It is clear that more discussion has to occur between progressive macroeconomists to search for ways in which our differences can be resolved. In general, I believe the answer lies in rejecting the orthodox paradigm outright and gaining a sharper appreciation of how financial markets actually work. It is very different to the way that orthodox macroeconomics textbooks pretend they work.

A further erroneous claim is that by using public outlays to provide a better infrastructure for the middle-class to watch high-speed IPTV the Government is reducing its scope to reduce hospital waiting queues or improve public transport systems or ensure public schools are first-class.

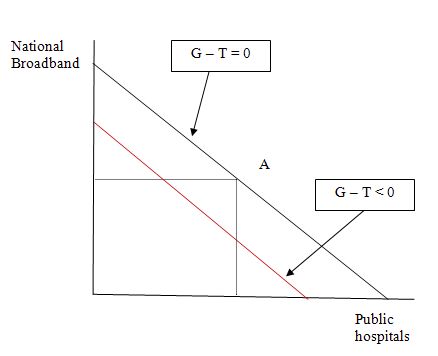

This claim stems from the underlying bias that the budget should be balanced. Take the following diagram which depicts two alternative uses of public service provision.

So the budget will be balanced if (ex post) tax revenues are equal to public spending. Assume the government has only two spending options – national broadband and public hospitals (the latter could be considered all other public options).

The downward sloping line depicts all combinations of spending on the two options that would be consistent with a balanced budget. Point A is one such mix. The more spending the national broadband network absorbs the lower will be the provision of public hospital services along this line. The extremes are all broadband or all hospitals. This sloping line is just a “balanced budget possibilities” frontier.

The policy debate is continually being conducted as if this downward sloping line is a real constraint whereas, in fact, it is just a voluntary fiction imposed on governments by political forces of the right.

The point is that the sloping line is an artificial (ideological or political) constraint and thus has no economic or financial basis.

The Australian government has actually imposed an even harsher voluntary constraint (the red line) because it is trying to pursue budget surpluses even though there is more than 12.5 per cent of available labour resources idle.

Further, while an increased provision of both hospital care and the national broadband network is entirely dependent on the availability of real resources and has nothing to do with financial capacity, the point ignored by the neo-liberals is that such an increased provision can actually ensure a wider set of possibilities for the private sector.

The NBN Co Business Plan makes a convincing case that the private sector will enjoy enhanced benefits as a result of the higher quality broadband infrastructure. So in fact the social returns (taking into account all the externalities) are likely to be very significant.

The whole discussion of rates of return is misleading. In a future blog I will address what criteria should guide public sector capital infrastructure provision.

Conclusion

We need a fundamental re-think about how the role and status of the national broadband network. It should not be considered in commercial (private market) terms. Using commercial logic is likely to lead to under provision of the infrastructure and excessive pricing of its services. The social gains alone are likely to be significant.

Further, it is clear that building a first-rate broadband infrastructure will also increase employment growth (the sheer size of the investment will do this) and stimulate all sorts of new private businesses to innovate in the areas noted in the previous paragraph. So the private sector spins off the public infrastructure but not in a way that compromises the fundamental efficiency and equity aims of the exercise.

Whether you want private retail providers to exist is another question that I might address another day. But if there are significant social returns (not accounted for in the NBN Co’s business plan then the “rate of return” is likely to be much higher than they have estimated and therefore the wholesale prices on offer could be much lower – or even zero.

Whatever, the provision of public infrastructure does not have to earn commercial returns.

That is enough for today!

It’s like the neo-libs are holding public services hostage. “Choose which one will live and which one will die!” The GBC is the imaginary gun.

In Brisbane, we only got a proper sewer system in the 60’s. Imagine if that had to go through a cost-benefit analysis. Good thing Turnbull wasn’t around to raise a fuss about how future advances in technology would make a sewer system a white elephant.

In An Essay On Principles Of Debt Management 1963, in Fiscal and Debt Management Policies James Tobin said

Its a nice article and Tobin clearly understands things. Now somewhere in this article, he messes up with money multipliers but lets just give him the benefit of doubt. He lived in the Anglo-Saxon world and probably hadn’t read Dennis Robertson or Nicholas Kaldor.

Unfortunately, saying anything beyond what Tobin said is going for the overkill. And that overkill is likely to produce all kinds of misinterpretation of the credit nature of money. The fact that there is no neat way to distinguish monetary management from debt management had led the Chartalists to conjecture that it is silly to issue debt and ideas as such. The production sector’s investment decision may not have sensitivity to interest rates one normally sees in the real world, but consumers have. The low interest rate environment engineered by Alan Greenspan did play a part in households’ speculating on real estate. Now MMT argues that taxes take care of aggregate demand. Now there is some crazy logic here. Taxes reduce aggregate demand but may not do the whole trick. The situation in the US is a proof of this fact. What are you trying to say ? On the one hand, you argue that US households were overtaxed and on the other hand you want to control asset price bubbles by taxing ????

Its true that more regulation would have prevented a few things from happening, but c’mon – enough to prevent an asset bubble ?

Then there is this theory of the US fiscal policy *forcing* the private sector to borrow! Now this is funny – thats an argument that budget deficits are exogenous. Its true that the fiscal policy was tighter. However it was the private sector itself going into higher debt by increasing its propensity to consume. The argument of being forced would have been true if the propensity had not changed.

The external sector is crucial to understanding Macroeconomics. The way the international monetary architecture is set up shows how money is credit and not Chartal. If there had been only one country in the world, would money be Chartal.

So how does my comment about debt management relate to Open Economy Macroeconomics ?

Government securities plays the role of settling for international debt. The two WMs say

This can be given a chance to be promoted to truth only if ALL exports to Australia are invoiced in AUD. “FEATURE ARTICLE: EXPORT AND IMPORT INVOICE CURRENCIES” from the RBA gives a different picture. Imports are invoiced in USD more than 50% of the time. Trade deficits are the result of competitiveness of local producers versus the rest of the world. Keynesianism roolz.

Amazing I have written about this so many times. The argument doesn’t even go beyond this. Then I see a comment which assumes that imports are in the local currency!

Then

and

It is true that after 1971, the government (“the State”) no longer has to make the currency convertible. However, in the present world, the IMF for example uses phrases such as fully convertible and capital account convertibility Some nations do not allow full convertibility on the capital account and there may be other restrictions such as non-resident converitibility. It can however be argued that the last one is insufficient to prevent capital flight. This happens through the international arrangement the banking system has put in place.

Its a huge MMT assumption that foreigners are mousetrapped. I do not know where it came from – its probably from the Chinese example of selling goods to the US where China’s main motivation is getting hold of Treasury securities – the modern equivalent of Gold – and not wishing to sell it off because their import dependence gets invoiced in USDs.

All items on the balance of payments (in the IMF format or the “Pink Book” format are processed through the correspondent banking architecture – via the Nostro/Vostro accounts. When Australia makes imports, the Australian banking sector credits the importer’s AUD account and gets into an overdraft at its foreign correspondent account. The Australian bank (“the respondent”) has three choices:

a. Buy foreign currency for AUD

b. Borrow in foreign currency

c. Enter into a currency swap.

Option (c) may be preferable, but in general all three are used. The banking system may also use some derivatives in case (b). The Australian banking system is thus indebted to the rest of the world in foreign currency, even if it may have hedged movements. If there is capital inflow, some of the above is reversed. However, foreigners have to be attracted to purchase AUD denominated securities. Normally MMT presents the story as if foreigners come in a ship and sell their products in exchange for “worthless paper”. Its as if their sales are restricted from the supply side. Plus treating money as if it is endogenous locally but exogenous as far as international trade and finance is concerned.

What about capital flight ? It is not surprising that most nations constantly struggle to put restictions on capital movements. They are not always successful. Its simple to see why foreigners may not get mousetrapped. The simplest way to see it is by studying illegal flows – using fake import bills. The IMF bans restriction on current account convertibility. However there are legal ways in which capital can fly. Let us say foreigners are invested in Australia and want to make a capital flight. A simple route to use is non-resident convertibility. Another way to see is this: let us say PIMCO banks with JP Morgan, New York and wants to sell AUD-denominated securities. It instructs JP Morgan to do that and JP Morgan sells them on behalf of PIMCO and credits PIMCO’s USD account. JP Morgan’s Australian correspondent will credit JP Morgan’s AUD account. It may seem that foreigners are still mousetrapped with AUDs but its not so. Some version of the reflux principle may he used here – JP Morgan may retire a currency swap with the amount credited – in which case, foreigners have made a capital flight.

Lots of mental modeling above – but a general case can be made for proving that no mousetrapping can occur and that ALL money is credit. The CGSM discussion paper authors may not know sectoral balances but come tantalizingly close to describing some things well.

Repeat Tobin’s wisecrack:

MMTers keep claiming Keynesians do not understand central banking operations. This is a challenge for them to talk in terms of the international correspondent banking system.

I hope Anon comments on this. He/she has not agreed on many things I have said over the past so many months (but we agreed on so many things on a different matter!), but would still like an opinion.

Ramanan:

One very quick thought train on an interesting essay (perhaps more somewhat later):

I think the crux of the currency issue is whether or not the liabilities that reflect the cumulative capital account surplus are denominated in local currency or not (e.g. US dollars).

That’s the end game for the beginning of the currency argument – rather than the currency in which the trade account is being invoiced.

The currency mix of capital account liabilities should be observable – e.g. whether or not the sovereign has issued foreign currency debt, etc.

A point I’ve made previously is that you won’t find the big banks taking massive naked short positions in the dollar. Rogue operations maybe; but not the center of gravity as in a civilized, relatively risk supervised commercial banking system (e.g. Australia).

In other word, the end game for the beginning of the argument is the degree to which the local economy has shifted the potential foreign exchange risk associated with dollar invoicing a trade deficit over to the source of the net capital inflows.

P.S.

“The two WMs”

🙂

Anon,

Thanks for your input. Will reply. In a hurry. Intervening to clear some typos crediting importer’s account should be debitting etc. (Before anyone uses it to dismiss my argument. )

At several points Bill says that given excessive unemployed resources, broadband can be paid for with printed money. Agreed. E.g. he says government will pay for broadband “like it pays for anything else by signing cheques and crediting private bank accounts..”. But I don’t think the printed money point is relevant here.

If the social and commercial costs and benefits of broadband compare favourably to the equivalent costs and benefits of ALL OTHER possible uses of scarce resources when the economy is nowhere near capacity, then broadband will also compare favourably when the economy is at capacity, and broadband CANNOT be funded by printed money.

So is the printed money point relevant?

Anon,

More thoughts. I agree with you about banks behaving in a civilized way etc., and going by commentators on this blog, I would imagine that Australian banks are doing good in that aspect.

That is the reason I brought the currency swap – option (c) in my story above. It hedges movements in currency. I will provide a reference in the next comment which will appear tomorrow only – its a book written by two currency traders.

A perfect riskless system is difficult to achieve because if a nation is paying a lot in imports, as a whole it is increasing its indebtedness to the rest of the world, which can be shown by going through some BP/IIP analysis. Banks may somehow insure against movements but not all.

I think currency swaps are a standard technique to achieve this and the Reserve Bank of Australia also shows some analysis on the banking system in the international context. To complicate matters, banks also raise money in foreign markets, independently – and one shouldn’t conclude that they are doing it for other purposes. Its also partly because international payments flow through the correspondent banking channel.

There are advantages of course of issuing liabilities in the local currency. Governments do not face issues in borrowing for example. Another advantage is that if the currency depreciates, there is no capital loss on liabilities. If the liabilities are in foreign currency, more has be earned to service the liabilities if the currency keeps depreciating.

Now the question is what is currency itself and I believe that there is no way of defining it without going into circular arguments and illustrating with a few examples. All attempts to define it keeping “Money is Credit” in the sideline is doomed to a failure.

We agree that it is better to have liabilities in the local currency – but another argument I presented is that foreigners’ holding is not “mousetrapped”. That is why one sees so much talk of capital controls in developing nations. That is why I quoted a few things in my first comment. Foreigners cannot be guaranteed to hold your liabilities if you persist running current account deficits.

Coming back to banks, they may face huge risks if there are outflows. Many times, governments try to rescue the banking system by borrowing in foreign currency. Governments spend in local currency and there is no use of borrowing in foreign currency. The effect however is to provide relief to the banking system. There is a paper by Brad Setser and Nouriel Roubini on this. Forget the fact that they may make Monetarist claims in a few places but they make good points on many issues. ”

“A Balance Sheet Approach to Financial Crisis” at IMF’s website.

I understand that there are zillions of arguments here – starting from “let the currency depreciate, exports will increase” which I am completely against .. but I understand that the arguments can continue no end.

However, what I am claiming is that it is dangerous for a nation to not pay attention to exports and persistent current accounts are usually cured via the IMF way – restrict demand. Current account deficits themselves restrict demand and plausible future government action – restricting demand – does more damage. MMTers however argue that the opposite should be done to cure the demand leakage through imports!

I see the MMT argument analogous to Milton Friedman’s arguments in the days Monetarism became popular. He agreed that central banks do not control the money supply but blamed it on the central bank’s incompetency.

More importantly I see the causalities itself being messed when things start getting described in the way “net save in A$” etc.

Australia’s Treasury’s quoted above says many right things – importance of government debt in the international context.

Also, there is a difference between banks acting as intermediaries to bring supply and demand equality for foreigners’ demand for local currency and payments on import invoices versus banks as banks and converting currencies.

Page 103 “7.5. Cash Management with Forex Swap” here on currency swaps and Nostro/Vostro accounts.

http://ajaxfinancial.com/downloads/Practitioner_Guide_to_Forex_Trading.pdf

Ramanan,

Very interesting posts. With a nod to anon’s comment, I would add that the important thing is the currency that the “cumulative capital account surplus” (ie net foreign debt) is denominated in.

In the case of Australia we have the equivalent of about AUD 650 – 700bn of net foreign debt and virtually all of this is denominated in AUD.

Gamma,

Thanks for the update. Do you have a source? Most likely RBA, I guess. Note you have to be careful about denomination of the debt and “currency exposure”.

5308.0 – Foreign Currency Exposure, Australia, March Quarter 2009

looks like the one. Only that I have to study how to analyze this.

My comments are just part of the story. More importantly I am trying to prove that it doesn’t really matter (too much). That is surprising, given the importance I have placed on the currency in my previous comments!

The reason I place so much importance is that the arguments I am critiquing begin giving so much attention to currency.

The logic roughly is that while its advantageous to be liable to foreigners in your own currency – don’t face depreciation risk etc, you still bear the risk of capital flight. You cannot mousetrap foreigners. That depends on how foreigners like your growth story and how well the nation does in foreign trade.

Some complicated logic there – hope you ponder over it with some thought.

Re Ramanan @ 23:52

”The low interest rate environment engineered by Alan Greenspan did play a part in households’ speculating on real estate. Now MMT argues that taxes take care of aggregate demand. Now there is some crazy logic here. Taxes reduce aggregate demand but may not do the whole trick. The situation in the US is a proof of this fact. What are you trying to say ? On the one hand, you argue that US households were overtaxed and on the other hand you want to control asset price bubbles by taxing ????

Its true that more regulation would have prevented a few things from happening, but c’mon – enough to prevent an asset bubble ?”

I don’t recall an MMT argument that asset bubbles be prevented through an increase in taxes. I believe the MMT argument is that asset bubbles should be controlled through regulation. I recall Bill Mitchell noting the housing price bubble could be dealt with by tighter regulation of mortgage lending. I don’t follow why this seems so preposterous to you. When discussing an increase in Canadian house prices (less extreme than in the U.S. but still substantial), Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of Canada, said almost precisely the same thing as Bill perhaps a year and a half ago in a committee hearing of the Canadian Senate. Since then the Canadian Banker’s association has asked the Bank to restrict mortgage lending and it has done so. Not surprisingly house prices have begun to weaken and are expected to continue to do so next year as a result of the regulatory changes. The suppression of house price bubbles through regulation is not an MMT solution, it is simply common sense, and it works.

If regulatory control seems preposterous it is because the banking system is not properly regulated, not that regulation won’t work. Of course inadequate financial regulation is a major problem of the U.S. economy.

hi ramanan, you might find this usefull

http://www.rba.gov.au/publications/fsr/boxes/2010/mar/b.pdf,

“Then there is this theory of the US fiscal policy *forcing* the private sector to borrow! Now this is funny – thats an argument that budget deficits are exogenous. Its true that the fiscal policy was tighter. However it was the private sector itself going into higher debt by increasing its propensity to consume”

budget deficits are to an extent exogenous ramanan, due to automatic stabilisers coming into play, and whilst its not the whole truth when it comes private sector dissaving as you have indicated, government surpluses draw savings from the private sector.

so our surplus fetish that seems to be doing the rounds at the moment doesnt help in terms of private sector savings

only have to look at rba data over the last 20 or so years to understand that evry recession or near recession has been preceeded by a series of budget surplus, which have exacerbated the debt addiction of the private sector.

Dear Ramanan (at 2010/12/20 at 23:52)

First of all your comment is very tangential to the specific post and reads like a lecture from the soapbox.

Second, Tobin was a deficit dove who believed that the government budget constraint was a binding ex ante financial constraint. In a fiat monetary system that is totally inaccurate and hence his macroeconomics is questionable at least. I would not be using him as an authority.

Third, you are too willing to set up straw persons. You say:

When commenting on my blog please do not verbal me. Attribution is important.

(a) My understanding of MMT is that taxes are but one policy instrument to influence aggregate demand. Your assertion is thus inaccurate. Depending on the circumstances, the nature of the spending shock, the distributional complexities involved tax changes will usually have to be accompanied by spending changes in levels and composition.

(b) What situation in the US? When you ask “what am you trying to say”, given that you are addressing my post I assume you are asking what am I trying to say. In relation to what? The comment has no context or meaning as it stands. Where have I ever argued that US households are overtaxed? If you are referring to someone else then please go to their blog and comment there. Otherwise, if it is relevant to my post, please attribute specific comments (like this) to the author. For the record, I have never said that US households are overtaxed.

You then continued in this “straw person” argument by saying:

(a) Which theory is that? Where have I actually written that US fiscal policy forced the private sector to borrow. I think your lack of understanding of what I have written is the “funny” aspect that is being revealed. For the record, I have never said that US fiscal policy forced the private sector to borrow in the sense that the government directly coerces the private sector in some way. The situation is that if the government is intent of using its discretionary fiscal capacity to squeeze private purchasing power then the only way the economy can grow (when there is an external deficit) is if the private domestic sector goes into deficit (which means increasing its indebtedness). It is the income adjustments that follow the push for fiscal austerity that promote the dynamic in the private domestic sector in that case. Then bring in increasingly aggressive financial engineering working within newly deregulated financial markets and the dynamic is reinforced. Yes, the growth in private debt “finances” private spending which keeps economic growth going and tax revenues strong. But if the private sector didn’t increasingly accumulate debt then the economy would collapse because of the fiscal drag and the budget surpluses would vanish – as we have seen in the crisis. Macroeconomics is about how aggregates push individuals around.

The fact is that whenever the US government has run a surplus, a major economic downturn follows on its heels. There is no coincidence.

(b) The budget outcome has an exogenous component (the discretionary policy choices) and an endogenous component (the automatic stabilisers). I have never said any different.

The rest of your comment contains material that you have noted before.

At the end of it all, we are still waiting for you to come up with an example of an advanced country running a full fiat monetary system with flexible exchange rates and no government debt denominated in foreign currencies that has seen its currency collapse because it has run a budget deficit. You claimed that was the norm. We have been waiting for you to produce such an example for some months.

Your only effort was Iceland and that fails the test. I would stop looking though – you won’t find an example which tells me that your notion of the external constraints are exotic to say the least.

best wishes

bill

“Lots of mental modeling above – but a general case can be made for proving that no mousetrapping can occur and that ALL money is credit.”

i’ll have to think about this mousetrapping issue, but i dont think thats the problem, whether i have to pay in australian dollars, or american or euro’s.

the viability of the currency in terms of foreigners accepting its convertibility into other acceptable currencies is the issue.

at source local currency denominated bank accounts are being credited and debited, even though conversion into other currencies may be taking place.

whether or not foereigners wish to hold local currency denominated assetts will largely be determined by the internal mechanisms within the domestic economy that maintain the value of that currency, such as the taxation power of thegovernment , the productive potential of the economy , and the prices the government is willing to pay for goods and services.

forex speculative plays aside, ultimately the value of the currency will be determinded by fundamentals.

i have difficulty with the idea that all money is credit,

there are two sources of currency into the economy, one is government created fiat(deposits) and the other is private bank and central bank created credit deposits,

so at source government created fiat money may be an interest bearing assett for a non government private sector entity, but thats a discretionary operational constraint, not a fate a compli.

its possible that government injection of nett financial assetts can be used for leveraging by the private sector, but just as easilly it can be used for investment and savings,

so i dont understand how all money is credit , it will depend on whose balance sheet it ends up in and what purpose its used for

In the OECD, this last cycle had house price bubbles — measured in terms of price to income ratios — in the U.S, France, Italy, U.K, Canada, Australia, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Spain, and Sweden.

You didn’t get bubbles in Switzerland, Germany, Japan, and Korea.

Of course Japan had a previous real estate bubble 🙂

//www.oecd.org/dataoecd/41/56/35756053.pdf

And I would throw in Latvia as well as eastern europe in the bubble camp. I’m not sure about Latin America — perhaps someone else can chime in.

It’s difficult to argue that this is all due to poor regulation, as these nations had different regulatory regimes.

Households are payment constrained, and for a given payment, the amount borrowed goes as 1/rate. So a drop in the rate from 7% to 4% is going to expand purchasing power by 175%. Now maybe with good regulation, that’s only 150% increase, and with poor regulation, you get a 200% increase. Germany has high downpayment requirements, for example, so perhaps there households could be downpayment constrained. But Canada’s house prices are more bubbly than the U.S., and their banks are supposed to be well regulated.

There is a role for regulation in influencing the severity of the bubble, but at the end of the day, falling interest rates, for a given level of income, will lead to asset price increases. It may not happen right away, or in all cases, but it generally does happen.

Bill said:

“The press conference today (when the Prime Minister released the report) was dominated by discussions of pricing. There is no reason why the NBN Co should seek a commercial return at all. This is a public good that is being provided.”

What is the “public good” being provided? I would not see broadband internet as a public good, personally. To me a public good is a something that is “useful” but is very difficult, inefficient or impossible to charge users for, and hence the private sector will not provide them. For example, roads and parks are public goods. It would be hugely inefficient to try and charge every person who benefits from a particular road or park individually, so they are provided by governments as public places.

I would agree with the NBN plan that the network should seek a return that basically covers the risk-free rate. After all 99% of the benefits of having a broadband network accrues to those who use (and can be charged for using) the network. I can’t see any sort of greater “public” benefit that might justify it being provided as a free or subsidised public good. Can anyone make a case that there is a public benefit involved?

That is not to say I disagree that the government should be involved in providing a broadband network. I think there are good reasons for government involvement. Most important, this broadband network MIGHT be a natural monopoly, and hence better provided by government than by a private monopoly.

Gamma:

I think it’s fairly easy to make a case that the NBN is a public good.

First of all, data pipes are very useful. We started with telegraphs, then we needed phones. Now we need internet. We have squeezed a lot out of our copper, but it’s reaching it’s limits. Fiber optics will be a huge step up. This will facilitate far more information transfer than before. Our company, for example, would benefit greatly. We need to send councils and road authorities many gigs of road data every month. The NBN would be awesome for us.

I don’t think public goods are about how you charge for them. I think it’s about how they get provided in the first place.

As for the NBN being something the private sector can provide, I just don’t see how. For one thing, it’s a highly centralized piece of infrastructure, like electricity, gas or water lines. You need to lay cables in public spaces all over Australia.

Another problem is you need to do it all at once. Doing it in a piecewise fashion would not work. This is because any individual length of fiber optics would be wasted due to bottlenecks elsewhere. So the cost-benefit of each single line is terrible. It’s only when all the bottlenecks are eliminated that each line become valuable.

On top of this, the timeframe for returns on investment might be fairly far off. It won’t change the country overnight, but at some point there will be a huge amount of critical services that require it. It will seem dead obvious in hindsight.

It’s something that requires a massive, simultaneous national effort with very undefinable (but real) benefits. No way the private sector would ever touch this. Otherwise they would have done it already!

Bill

“At the end of it all, we are still waiting for you to come up with an example of an advanced country running a full fiat monetary system with flexible exchange rates and no government debt denominated in foreign currencies that has seen its currency collapse because it has run a budget deficit.”

With respect to your above comment to Ramanan. The Russian crisis in 1998 was an example of a sovereign country eventually coming to ruin attempting to run large fiscal deficits, even with the debt denominated in local currency. They did not have a fully floating exchange rate, however. But would the situation have been any different if they had one? If the ruble was a free float, the exchange rate probably would have declined over a longer period of time rather than the sudden adjustment that occurred after they abandoned their peg. I fail to see how this would have avoided the massive inflation that followed.

RSJ,

I read a bit about housing bubble in Poland and it was a result of a certain policy. An assumption was made that the housing shortages problem would have been solved if enough cheap credit had been provided. The invisible hand of market was supposed to act. It worked very well – everyone was feeling richer. Just imagine a 40sqm appartment in a provintial city (not in Warsaw) being priced at 80000USD in 2007 – while wages were still 3 times lower than in the USA.

What kind of regulation are we talking about? People were allowed to take loans for more than 100% of the value of the property in a foreign currency (as joining Euro was only a matter of time). Actually the loans were mostly provided by foreigh (European) banks.

What is the most stunning is that you can again get them there. No I haven’t made this up. Every attempt has been made to restart the bubble.

link_http://www.kredythipoteczny.net.pl/

MBank:

Hipoteki na 110% wartości nieruchomości! up to 110% value of the property

Deutsche Bank:

do 100% wartości nieruchomości także w walutach obcych (up to 100% value of the property, also in foreign currencies)

kredyt nawet na 40 lat, do 30% na dowolny cel (up to 30-40 years term, for any purpose)

wymagany dochód min. 6 000 netto (minimum net income USD2000/month)

It is not a failure of regulation it is the lack of any intention to regulate. Fiddling with interest rates won’t make much difference if most of the borrowing is Ponzi-like as higher interest rates would kill the business lending instantly.

The root cause of the crisis is the profound paradigm change which happened in the West in 1980-ties. I think this may have affected not only in Poland, USA and Australia but it also explains all the housing bubbles.

Now back to the main set of questions raised by Ramanan. To me the key issue is whether we live in a “money is credit” world what might have been true to some extent during the gold standard era or whether we assume that the state money is not debt (bank money certainly is backed by debt 1:1)

I think that we live in a fiat system which is dressed up to resemble the system from the gold standard era. Again this is based on certain assumptions and normative decisions.

We have to acknowledge that the dispute is about the axioms. If governments have to borrow money before they spend (which is a normative statement) no matter how much we are convinced that from the functional point of the system is fiat and money is created by spending, destroyed by taxing or bond sales etc. – we have to acknlowledge that the government can run out of money (like in the UK) due to the arbitrary constraints it imposed on itself. These constraints only make sense in the context of monetarism and their violation would result in hyperinflation according to that theory.

To me the core of MMT is about acknowleging that from the functional point of view these constraints are artificial in the fiat money era – they are a result of certain political climate and decisions.

To me the real axiom is that private property rights are so sacrosaint that the government has to act like one of the equal agents. There is no true sovereignty because it would violate the assumption that the government must not create net money “out of thin air” without creating a corresponding liability and asking financial markets to price that liability. In that sense the current system is not fiat – all the money is private money because the government is just like a city council – without the seignorage. And central banks are “independent”, just targetting short term interest rates, forex markets have to operate in a certain way described above, etc…

Until commercial banks have to be bailed out of course – then it’s time to socialise the losses.

I certainly have a problem with the current axioms and I don’t think that the system is stable unless it is in a permanent recession.

Grigory,

I agree with most of what you have written, but I don’t think you have made the case that the NBN is a public good.

Perhaps we are using different terminology here. I am using the term “public good” in it’s economic sense, not simply to mean something that is provided by public sector. I agree that there is a strong case for the NBN to be provided by the federal government, but this does not make it a public good.

A public good is something that can be used by members of the public for free or where significant benefits accrue to the the public for free. It is not practical or efficient to charge people for the benefit they obtain. A park is an example of a public good. It is not really practical to charge people directly for using and enjoying a park, and further some benefit accrues to people who don’t directly use the park (they may have a view of the park, for example).

Therefore there is a good justification for provision of things which are public goods by governments for people to use freely. But what are the public or social benefits that will accrue from the NBN in excess of the private benefits? This is a genuine question….I have an open mind.

Bill has written:

“Great public infrastructure projects generate massive social returns. It is possible that privatised benefits are small but the social benefits enormous…..All the evidence available points to the social returns being significant.”

Where is “all the evidence” for this? For me some justification is required.

Bill,

My comment was not tangential at all. It is related to what you have quoted and the links you have provided on issues such as interest rates, government debt and the external world.

I am not verballing, whatever it means. I am just trying to get into an honest to goodness discussion on international movements and its relation to fiscal policy. Unfortunately none of my comments move forward about specific points such as import payments in a different currency. If one starts with a false premise – a story where imports are paid in local currency – as if its the generic case then there has to be someone to challenge the proposition. In your story, foreigners land up to sell their products to accumulate foreign currency of the land and its the story which I am challenging.

As far as exchange rate falls are concerned, I think you gave it away yourself – Australia’s currency fall. I mean do I need to even go and find out examples. Plus what is the claim there – a nation can import like crazy and no problem ??? Where does it stop ? How much can the external debt go ? 300% ? Plus never said budget deficits cause currency collapse. There is a a huge story here about the various causalities involved and if I gave the impression that I said “budget deficits create currency collapse” – I don’t even know where to start explaining my stand.

Did Australia have full employment during the fall ? You say the sky didn’t fall but politicians in Australia say that Australia faced the recession that wasn’t.

At any rate – there are lots of examples in

“Are Pegged and Intermediate Exchange Rate Regimes More Crisis Prone” by Andrea Bubula and Inci Otker-Robe (IMF) – appendix 4

“Current Account Reversals and Currency Crisis – Empirical Regularities” by Gian Maria Milessi Ferretti and Assaf Razin (IMF) -appendix 1

“Exchange Rate Regime Choice and Currency Crises” – Ahmet Atıl Aşıcı (ERF Annual Conference) – Table A.3

Now I havent had the time to analyze them in detail and economists have fought with each other themselves on this. So you can always come up with an exception saying the government had $x in foreign debt. All governments have debt in foreign currency and even Japan managed to retire it last year only. Plus even if x=1 cents, its a problem ?

At any rate I dont see why Iceland fails the test – that too miserably. Had the government not bailed banks by borrowing in foreign currency, the nation would have shut off from the rest of the world. The banking system holds a special position in international transactions. Nationalize the banks – you end up picking up their foreign currency denominated debt as well, going against the MMT guideline! Self contradictions there.

As far as other matters about fiscal policy that you noted are concerned, will come back and quote specifics.

At any rate, what I am trying to say is that it is difficult to give up interest rate targetting. If there is an asset price bubble, the only way you can stop is by increasing taxes in that case and its not guaranteed to do so. It will create further unemployment when there is already no full employment. In that case you hike interest rates. You also adjust interest rates due to external factors – most third world nations do that and it seems – going by the CGSM article, important for advanced nations such as Australia as well. I know the sectoral balances too well. When you say the US government ran a surplus, you should also attribute it to the role played by the private sector.

Its the ultimate rule of macroeconomics – fiscal policy is useful as long as the foreign sector permits it! Its no surprise that nations give so much importance to the external sector. They can’t be fooling themselves all the time.

Keith,

A short answer, if you don’t mind – zero interest rates and you can prevent asset price bubbles ? Here in India, the regulations have been tighter than most nations – hasn’t prevented asset price increases.

More importantly, interest rates are important when considering the external sector as well.

Mahaish,

Do not see any disagreements, but can be talk specifics ?

Adam, I’m ready to believe the worst for Poland, sure, but what about Sweden? Alternately, if pretty much all the OECD, as well as North America, can’t figure out how to regulate the banks, then why do you remain confident that it can be done? There are real issues here — e.g. during the bubble incomes go up, balance sheets appear stronger due to more equity, default rates are low, etc.

About interest rates, well this has been beaten to death. I don’t care about government needing to borrow or not. It doesn’t cost the government more to create a bond than it would to create money. The issue is the private sector, which does need to borrow. Government borrowing or not borrowing is relevant only to the degree that it distorts private sector rates. Rates are not exogenous, if they are too high or too low, then the economy will be hurt. It’s not the quantity of money per se, but the price of money that matters.

Gamma,

The premise of your question is that government shouldn’t attempt to add value except when it is theoretically impossible for the private sector to do so.

I don’t think this is realistic. A more nuanced version would be to admit that there are value creating opportunities overlooked by the private sector, and government can add value by stepping in to fill the gap.

The private sector hasn’t historically been effective at funding large scale infrastructure.

Look, for example, at ports. In the U.S. at least, most ports are public.

It’s not hard to charge someone for using a port. But creating the port creates a new market, so you can’t charge people up front. You have to first build the port, then see who uses it, and those are the people you charge.

These types of big, risky projects are often not undertaken by the private sector, and the government can add value by doing what the private sector fails to do.

Same for interstate highways, canals, railroads, etc.

I don’t think it has anything to do with the good being rival, so much as the private sector being too risk averse and/or short-sighted to really fund long term infrastructure investment. It just doesn’t happen on a large scale. If, based on principle, the U.S. government refused to build any airports, sea ports, or, for that matter, the internet, we would be much poorer as a nation.

Therefore historically governments provide infrastructure services, particularly when those services increase efficiency and promote the creation of new markets, even though it is pretty easy to charge fees for the use of the infrastructure.

You can argue that there are spillover effects — e.g. living next to a subway stop increases your property value, but that seems pretty weak. The same is true for a good restaurant. The fact is, a private sector actor *could* build public transit if they wanted to — that happened with San Francisco’s cable cars — but most of the time they lack the desire and/or means to pull off large scale projects like that.

RSJ,

I have never said that just re-regulating the banks would stop housing bubbles. Much stronger political will is required (land taxes and capital gain taxes replacing income taxes, investment in social housing, planning policies) but obviously the most of the Western democratic countries may be unable to act quickly when the most influential social groups are having such a great time and bankers can lubricate the political system by lobbying.

Let’s see how it works in a countr with a different system (China) whether they succeed in prickling the bubble or whether they end up having the same mess as everyone else. My theory is that they’ll survive the artificial crash next year and power ahead but I may be wrong…

In regards to interest rates why do you think that they are distorted? They are used by the Central Banks as the main tool to regulate the economy and the error signal is CPI. This is probably one of the root causes of the problems. We have a simple PID controller where filtered error signal is applied to the input of the object. CPI inflation up – interest rates up. CPI inflation down – interest rates down. In that sense in the current system short-term interest rates are exogenous. Long-term rates may not be fully exogenous but this is a result of an arbitrary decision discussed in my previous post in regards to not using naked money creation as a tool. This sets other parameters of the system which are dependant as for example we cannot accumulate too much public debt while the “markets” determine bond yields. This puts a real constraint on the fiscal policy (limits deficit spending G-T) but this all is a result of some arbitrary normative assumptions.

Again to me this is a matter of designing the topology of the feedback loop and setting the working point of the system. The current settings lead to unstability due to Ponzi-type bubbles forming and as a consequence to long-term loss in potential GDP growth due to aggregate demand gap, high unemployment and low investment.

To me the only stable attractor in the current topology is a state of a permanent deep recession otherwise bubbles will form.

A slightly modified system can work at a different operating (bias) point what has been seen in Japan.

There can be an alternative set of parameters (interest rates, unemployment, particular taxation policy, GDP growth, exchange rates) which may or may not be a stable attractor. The error signal for MMT (as I understand it) will be productive capacities utilisation and the control input will be (G-T)

In that case G-T is assumed to be irrelevant on its own and long-term interest rates may be low. Nobody has proven that this will lead to inflation and bubbles forming if speclative behaviour is made less profiatble and actively discouraged. Banks will still limit lending only to these project which offer good return. Will it make sense to lend 110% of the value of the house for 40 years?

N.B. In China they are trying to maximize I (investment) and they use all the other parameters as control inputs – regardless what they are saying this is how they run the system to maximize GDP growth. The rest is irrelevant. “Whatever it takes”. This is their political choice.

Gamma:

“A public good is something that can be used by members of the public for free or where significant benefits accrue to the the public for free”

Does this mean that a toll-free road is a public good, while the Clem7 tunnel isn’t, because they charge money? Could you turn the Clem7 into a public good by making it free? If so, then the NBN can be a public good by making broadband free for all subscribers. Is this really the only difference?

As for public/social benefits that accrue from private benefits, do you mean indirect benefits? In other words, would I have to show how someone who is not a service provider or user benefits? Take roads, for example. Toll-free or not, they indirectly help a lot of people who don’t drive by providing a way for supermarkets to efficiently distribute food to shops, thus lowering prices. That is a clear social benefit.

First and foremost amongst indirect beneficiaries from the NBN would be companies that can now provide services they could not before. Whole new business models would now be possible. They are a third party, yet they gain from the NBN.

Another benefit is that it takes us closer to a massively parallel, distributed computing system. The PC you and I have at home probably wastes at least 90% of it’s clock cycles running idle. This computing power goes to waste. You can download programs that do computationally expensive protein folding simulations (to discover new medicines), but this sort of thing is network-limited. The app I described was itself only made possible by the speed increase from dial-up to broadband. Imagine if we could use a highly-networked computing grid to do amazingly high-res climate simulations, or earthquake predictions – these are tasks that require intercommunication between all nodes (unlike folding@home). Current broadband is nowhere near powerful enough to handle this. Essentially this would be the next revolution in supercomputing.

Those are two benefits I can think of off the top of my head. There will be countless other benefits no one can predict.

RSJ,

“The premise of your question is that government shouldn’t attempt to add value except when it is theoretically impossible for the private sector to do so.”

That was not my suggestion at all. I have no problem with a government providing services and infrastructure. I think the NBN is a reasonable idea. My objection is to the idea that the internet broadband is a “public good” and hence should be provided to all citizens for free, which is Bill’s suggestion. The justification for providing things to citizens on a free or subsidised basis is that there are significant social or public benefits which are not captured in the private transaction between buyer and seller – ie “positive externalities” to use the jargon. But where have these benefits been identified?

Personally I cannot see them and hence I agree with NBN plan that provision of broadband services should be largely on a commercial basis. In my view the vast majority of the benefit of high-speed internet accrues to the direct users of the network, who can easily be invoiced for the use.

To use your example of ports, do you think that they should be classified as public goods, and hence governments should stop charging fees to users of the ports?

Not all services and infrastructure provided by governments are necessarily public goods, and also not all public goods are provided by governments.

Gamma,

What’s the difference between public roads and public broadband?

The justification as far as I can see is that the government can build these things considerably cheaper than anybody else as they have no cost of capital. Therefore doing it communally is cheaper. In fact in almost all circumstances it is more efficient to do things communally. The problem is that humans tend not to work that way, as they are naturally selfish.

It’s precisely the same argument as that for open source software. Much better to build one operating system everybody can use freely.

Adam: To me the real axiom is that private property rights are so sacrosaint that the government has to act like one of the equal agents. There is no true sovereignty because it would violate the assumption that the government must not create net money “out of thin air” without creating a corresponding liability and asking financial markets to price that liability. In that sense the current system is not fiat – all the money is private money because the government is just like a city council – without the seignorage. And central banks are “independent”, just targetting short term interest rates, forex markets have to operate in a certain way described above, etc… Until commercial banks have to be bailed out of course – then it’s time to socialise the losses. I certainly have a problem with the current axioms and I don’t think that the system is stable unless it is in a permanent recession.

Exactly. This is the conservative presumption is to consider government as an equal market player in stead of acknowledging the vertical-horizontal relationship. This is what crowding out and Barro’s version of Ricardo are based on. The smart ones know about the operational reality of a fait system and have designed various ploys, legal and propagandistic, to neuter it in favor of “property rights,” aka treating money chiefly as a store of value which serves the wealthy that hold intergenerational wealthy in bonds.

These people also recognize the usefulness of the operational reality of a fiat system, which is why they have no problem with unlimited military expenditure to fund an empire that benefits their interests, as well as to socialize losses of the financial sector due to overreach. They are well aware of why the Nixon abandoned gold to support his Vietnam adventure along with the rest of the empire. We know from Warren that Laffer, who craved Reagan’s supply-side “voodoo” economics, was well aware of the operational reality of fiat, hence, that “deficits don’t matter” (Cheney). It’s also why W had no problem funding his Iraq adventure while cutting taxes and running huge deficits pro-cyclically.

It’s the liberals that are in the dark and being taken for a ride. Notice how the GOP recently led the charge against the deficit and debt in the name of fiscal responsibility and discipline, and then unabashedly forced extension of a huge tax cut that blows up the deficit and increases the debt. Of course, this is part of their stated objective of ending social welfare programs or privatizing them.

Bill @ Tuesday, December 21, 2010 at 9:57,

Regarding invoking strawmaning as defense, let me quote this from an old post

Now combined this with your latest comment, it may seem that we are splitting hairs here but we don’t have to.

But I am claiming that both the private sector and the government were responsible for the mess, instead of the sympathy shown to the private sector in the quote above.

Back to my original comment, what I intended to say was completely missed. In the scenario of the United States, with tight fiscal policy and low interest rates, asset prices kept increasing. If you argue that both fiscal policy has to be relaxed and use the “no bonds” zero interest rate proposal, its not difficult to imagine what would have happened to asset prices. On the other hand, taxes could not have been used in an environment where the private sector was in deficit.

The truth is that we live in an imperfect world and interest rates have to be moved around.

(Plus the external sector as well, but won’t go into that here).

Anyway

BIS Working Papers No 314 Chronicle of Currency Collapses: Re-examining the Effects on Output By Matthieu Bussière, Sweta C. Saxena and Camilo E. Tovar

In fact according to a Banco de Mexico report, the exchange rate had plummeted to around 15.5 around April-2009.

Mexico has a history of current account imbalances and a huge negative International Investment Position.