I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Very costly fiscal programs are needed

In yesterday’s blog – Our children never hand real output back in time – I canvassed the recent speech by Japanese financial market expert Eisuke Sakakibara who emphasised that the world recession will be protracted (until 2015 at least) because governments are refusing to support output and income generation with appropriately scaled fiscal interventions. It was a timely warning I think. But organisations like the OECD are pressuring governments to do exactly the opposite. They want governments to accelerate their pro-cyclical fiscal austerity plans – that is, withdraw public spending while private spending languishes. It is a purely ideological demand – and will worsen the recovery prospects of any country that follows that course – Ireland is our beacon! What is required at present are very costly fiscal programs – programs that utilise as many real resources as are idle. Such a strategy would be the exemplar of responsible fiscal policy management.

In their Economic Survey of Euro Area 2010 the OECD is once again lecturing the EMU member states that “(p)rolonged fiscal consolidation and reforms will be needed to bring debt to a more prudent level, increase the ability to withstand future shocks and to prepare for future ageing costs”. They are proposing “fiscal councils” and I will write a blog about that proposal maybe tomorrow.

Basically, the proposal is to further subvert the democratic standing of so-called “free nations” by creating “independent fiscal institutions, or fiscal councils” which have full autonomy (that is, are insulated from the political process) to determine appropriate fiscal policy settings and place pressure on governments to “comply with a numerical rule”.

The claim is that “good fiscal institutions are a necessary condition for achieving disciplined fiscal performance”.

The proposal is a mindless demonstration of the ideological position that elected governments should not use discretionary fiscal policy to counter-stabilise the fluctuations in the non-government spending cycle. Instead, an unaccountable (to us!) body of neo-liberals (mainstream economists) etc would pontificate over the government and enforce pro-cyclical fiscal positions – that is, enforce discretionary contraction when the automatic stabilisers were driving the budget into larger deficits as a result of weak non-government demand.

Anyway, I will examine the OECD documents on this topic in another blog.

But the underlying proposals coming from the major world economic institutions and the vast bulk of the commentariat tell me that we have not yet understood what has happened over the last three years or so, and what caused the events of the last few years – in the decade or more before 2007.

Eisuke Sakakibara has a good understanding. And in Paul Krugman’s latest Op Ed in the New York Times (December 12, 2010) – Block Those Metaphors – the problem is set out very clearly.

Krugman comments on the latest US tax-cut deal which he labels a “short-term boost” to the US economy. I agree with that assessment. He notes that of the economists currently supporting more fiscal intervention the overwhelming bias is towards a “short-term boost” to “jump-start the economy” etc.

The title of his Op Ed indicates that he doesn’t like the metaphors for the US economy – a “stalled car” needing a jump-start and other references being made to short-term, palliative care.

He says:

Our problems are longer-term than either metaphor implies. And bad metaphors make for bad policy. The idea that the economic engine is going to catch or the patient rise from his sickbed any day now encourages policy makers to settle for sloppy, short-term measures when the economy really needs well-designed, sustained support.

However before we get too excited, I remind readers that Krugman has maintained a consistent deficit-dove position throughout the crisis. He has acknowledged the need for fiscal support in the “short-term” but has insinuated that budgets should be balanced over the course of the business cycle.

In June 2010, he forecast a lost decade. In that Op Ed he said:

But don’t we need to worry about government debt? Yes – but slashing spending while the economy is still deeply depressed is both an extremely costly and quite ineffective way to reduce future debt … The right thing, overwhelmingly, is to do things that will reduce spending and/or raise revenue after the economy has recovered – specifically, wait until after the economy is strong enough that monetary policy can offset the contractionary effects of fiscal austerity.

In other words, public debt is a problem but not at the moment.

Deficit-doves are dangerous. They believe that when private spending is weak governments should run budget deficits but when growth returns the budget should go into offsetting surpluses and balance over the course of the business cycle. They argue that the mainstream approach to run budget surpluses or balanced budgets always provides no scope for government to counteract reductions in private spending and so such as strategy commits the economy to periods of recession and rising unemployment.

The intent of the mainstream (neo-liberals) is clear – it is an ideological dislike of government involvement in the “market” and so the fiscal rules aim to limit the socio-economic role of the state.

Deficit-doves think that deficits during period of growth are likely to “crowd out” private sector investment by competing for funds. However, this proposition really makes them part of the problem.

Clearly, at any point in time, there are finite real resources available for production. New resources can be discovered, produced and the old stock spread better via education and productivity growth. The aim of production is to use these real resources to produce goods and services that people want either via private or public provision.

So by definition any sectoral claim (via spending) on the real resources reduces the availability for other users. There is always an opportunity cost involved in real terms when one component of spending increases relative to another.

However, the notion of opportunity cost relies on the assumption that all available resources are fully utilised. Unless you subscribe to the extreme end of mainstream economics which espouses concepts such as 100 per cent crowding out via financial markets and/or Ricardian equivalence consumption effects, you will conclude that rising net public spending as percentage of GDP will add to aggregate demand and as long as the economy can produce more real goods and services in response, this increase in public demand will be met with increased public access to real goods and services.

If the economy is already at full capacity, then a rising public share of GDP must squeeze real usage by the non-government sector which might also drive inflation as the economy tries to siphon of the incompatible nominal demands on final real output.

Whether a rising public demand on the finite resources is desirable depends on what the alternatives are. I do not automatically think public use of resources is inferior and private use superior. The mainstream assertion that markets allocate resources efficiently and therefore private provision is better than provision by fiat (public) is just a myth. The financial crisis should leave us with no doubts that the “private markets” are dysfunctional and require public intervention.

Ultimately, when resources are finite political decisions have to be made by government as to which sector uses them. If the government determines that its political mandate requires more public use and less private use, then fiscal policy has to be used to ensure that the private sector can spend less. Please read my blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more discussion of this.

But the possibility of physical crowding out is not the same as the concept of financial crowding out which is a centrepiece of mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and which deficit doves have some sympathy for. This concept has nothing to do with “real crowding out” of the type noted above.

The financial crowding out assertion is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention. At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking.

The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

At the heart of this erroneous hypothesis is a flawed viewed of financial markets. The so-called loanable funds market is constructed by the mainstream economists as serving to mediate saving and investment via interest rate variations.

This is pre-Keynesian thinking and was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

So saving (supply of funds) is conceived of as a positive function of the real interest rate because rising rates increase the opportunity cost of current consumption and thus encourage saving. Investment (demand for funds) declines with the interest rate because the costs of funds to invest in (houses, factories, equipment etc) rises.

Changes in the interest rate thus create continuous equilibrium such that aggregate demand always equals aggregate supply and the composition of final demand (between consumption and investment) changes as interest rates adjust.

According to this theory, if there is a rising budget deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending.

So allegedly, when the government borrows to “finance” its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment.

The mainstream economists conceive of this as the government reducing national saving (by running a budget deficit) and pushing up interest rates which damage private investment.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost self-evident truths. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

Further, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. But government spending by stimulating income also stimulates saving.

Additionally, credit-worthy private borrowers can usually access credit from the banking system. Banks lend independent of their reserve position so government debt issuance does not impede this liquidity creation.

Anyway, after that warning digression, back to the main plot.

Krugman is absolutely correct in saying that:

The root of our current troubles lies in the debt American families ran up during the Bush-era housing bubble. Twenty years ago, the average American household’s debt was 83 percent of its income; by a decade ago, that had crept up to 92 percent; but by late 2007, debts were 130 percent of income.

All this borrowing took place both because banks had abandoned any notion of sound lending and because everyone assumed that house prices would never fall. And then the bubble burst.

What we’ve been dealing with ever since is a painful process of “deleveraging”: highly indebted Americans not only can’t spend the way they used to, they’re having to pay down the debts they ran up in the bubble years. This would be fine if someone else were taking up the slack. But what’s actually happening is that some people are spending much less while nobody is spending more – and this translates into a depressed economy and high unemployment.

Yes, basic macroeconomic principle – spending equals income. Income is produced with output and supports employment. At any point in time an economy has some finite productive capacity and it is aggregate demand (spending) that provides the motivation for firms etc to deploy that capacity.

Should the spending be insufficient to that required to fully engage all productive resources then we have an economic slowdown and this can easily become a recession as firms lay-off workers and the lost income multiplies through the economy – spreading to other firms and reducing their desire to employ workers in productive activity.

An economy can be constructed in terms of two broad sectors: the government sector and the non-government sector. We can further decompose the non-government sector into the private domestic sector and the external sector.

The government sectors adds to aggregate demand by spending and reduces demand by taxation. The private domestic sector adds to demand by consuming and investing and saving is thus a withdrawal of spending. The external sector adds to demand through exports but import spending (by all domestic sectors) reduces local demand.

Understanding these spending impacts allows us to clearly see what must happen if the private domestic sector is reducing its spending in order to net save. The only way the private sector overall can reduce its debt levels is to net save. As that process has unfolded, consumption and investment spending has fallen.

The US and most other nations run external deficits which drain demand from the local economy and are thus deflationary. So with the private domestic sector attempting to repair its “balance sheet” (reducing debt) and the external sector in deficit, there is only one sector left to fill the spending gap – the government sector.

Krugman acknowledges this:

What the government should be doing in this situation is spending more while the private sector is spending less, supporting employment while those debts are paid down. And this government spending needs to be sustained: we’re not talking about a brief burst of aid; we’re talking about spending that lasts long enough for households to get their debts back under control. The original Obama stimulus wasn’t just too small; it was also much too short-lived, with much of the positive effect already gone.

So to restate the fundamental first principle of macroeconomics – firms produce to meet expected spending. All output will be sold if spending equals the sum of all income. If an agent spends less than its income, output will go unsold unless another agent goes into debt and buys that output.

If there is a generalised net desire to save – output will go unsold and the stock build-up will lead to declining production and employment.

The reverberations of the lost incomes generate a downward spiral in output. In this situation, the economic outcome depends entirely on the policy response by government. If demand for private production falls but people still desire to work then there is no valid reason not to switch them to public goods production until private demand recovers. Unemployment results when the policy response inhibits this switch.

In a paper I wrote in 1999 I said the following.

Unemployment will occur when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account, but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns. That results in involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services and translates into decreased output and employment.

In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the desire of the private sector to net save, and thereby increase spending. This point is articulated in Post Keynesian theory but plays no role in the neoclassical/monetarist explanations of unemployment.

It is the introduction of “State Money” into a non-monetary economics that raises this spectre of involuntary unemployment. Extending the model to include the foreign sector makes no fundamental difference to the analysis and as we will private domestic and foreign sectors can be consolidated into simply the non-government sector without loss of analytical insight.

The only entity that can provide the non-government sector with net financial assets (net savings) and thereby simultaneously accommodate any net desire to save and eliminate unemployment is the government sector. It does this by (deficit) spending. Furthermore, such net savings can only come from and is necessarily equal to cumulative government deficit spending. National income accounting is thus underpinned by the identity; the government deficit (surplus) equals the non-government surplus (deficit). The systematic pursuit of government budget surpluses must be manifested as systematic declines in private sector savings. This is contrary to the mainstream rhetoric.

The non-government sector is dependent on the government to provide funds for both its desired net savings and payment of taxes to the government. To obtain these funds, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

National government spending is never inherently revenue-constrained. It is only constrained by what is offered for sale in exchange for its currency.

Returning to the textbook case (with a consolidated private sector including the foreign sector), total private savings thus equals private investment plus the government budget deficit. And, if we disaggregate the non-government sector into the private and foreign sectors, then total private savings is equal to private investment, the government budget deficit, and net exports, as net exports represent the net savings of non residents.

In general, deficit spending to be necessary to ensure high levels of employment.

This framework also allows us to see why the pursuit of government budget surpluses will be contractionary. Pursuing budget surpluses is necessarily equivalent to the pursuit of non-government sector deficits.

They are the two sides of the same coin. In recent years, financial engineers have empowered consumers with innovative forms of credit, enabling them to sustain spending far in excess of income even as their net nominal wealth (savings) declines.

Financial engineering has also empowered private-sector firms to increase their debt as they finance the increased investment and production. The resulting sharp decline in the desire to net save temporarily allowed the US government to realise a budget surplus, but the process was not sustainable.

The decreasing levels of net savings ‘financing’ the government surplus increasingly leverage the private sector. Increasing financial fragility accompanies the deteriorating debt to income ratios and the system finally succumbs to the ongoing demand-draining fiscal drag through a slow-down in real activity.

It is clear that this understanding does not recognise the validity of fiscal rules that are independent of the state of the spending in the other sectors. To state that the public budget should be balanced over the business cycle is to ensure that the private domestic balance will be equal to the external balance over the same cycle.

So if an external deficit persists (and there is very little chance that the US economy will start delivering external surpluses any time soon), then pushing the budget into balance(even if you could) would be equivalent to forcing the private domestic sector into deficit (equal to the external deficit).

In other words, the fiscal austerity proponents do not understand that private deleveraging when there is an external deficit must be supported by on-going budget deficits. That is not likely to be a short-term affair.

The deficits support economic growth and income generation which provides the capacity of the private domestic sector to enjoy some consumption growth (which, in turn, is likely to stimulate investment growth) but also provides the scope for that sector to save overall. It is in this sense that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) says that deficits “finance” private saving.

Without the deficits or with deficits that are inadequate (relative to the desire to net save), the economy stagnates and the process of private debt reduction becomes very painful and probably stalls overall.

In this context, Krugman says:

It’s true that we’re making progress on deleveraging. Household debt is down to 118 percent of income, and a strong recovery would bring that number down further. But we’re still at least several years from the point at which households will be in good enough shape that the economy no longer needs government support.

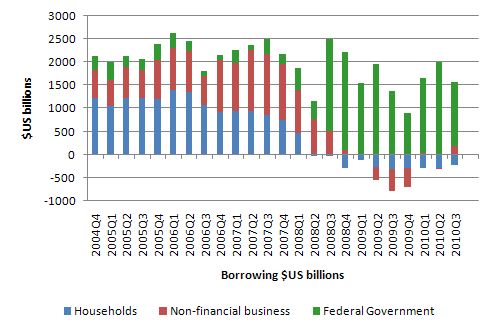

Now consider the following graphs. Some one sent me a link overnight to a page which had a version of the first graph displayed. The graph is based on the US Federal Reserve Flow of Funds data. Note to Reserve Bank of Australia: I wish we published the depth of flows data for Australia that is available to US researchers. That would be a more useful task than spending time creating unemployment and threatening household solvency by manipulating short-term interest rates.

The first graph shows total borrowing by quarter from the first quarter 2004 to the third quarter 2010 and is suggestive of the scale of the problem that the US economy faced as the private sector began to unwind its unsustainable debt positions. The particular page extolled the wisdom of this shift from private to public debt as saving the US economy but the comment displayed on that page were mostly hysterical along the lines of “US government eats US children by going on a frenzied printing money binge” etc.

The graph shows how quickly the “private debt binge” paradigm changed and the private sector withdrew their spending (implicit). The fact is that the government had to step in or else the US economy would have experienced a depression.

The debt dynamics just reflect the fact that the US government voluntarily issues debt $-for-$ to match its net spending. Although this behaviour is totally unnecessary it is nothing to be alarmed about. The US government can never be insolvent in its own currency and can meet any liabilities that are denominated in that currency. That status is not enjoyed by the non-government sector.

Please read my blog – On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose – for more discussion on this point.

So public debt is not equivalent or comparable to private debt. Please read my blog – Debt is not debt – for more discussion on this point.

Public debt is equivalent to private wealth. The Ricardians (Barro etc) tried to deny this – claiming that the deficits have to be paid back with higher taxes and so the debt today is a higher tax burden tomorrow. That claim has not foundation in reality – Please read my blog – Pushing the fantasy barrow – for more discussion on this point.

Anyway, given all of that, it is quite remarkable how little insight seems to be demonstrated on these financial market home pages, blogs etc – as indicated by the comments I read on the site referred to above which had a graph similar to my previous graph. More worrying is that (as the saying goes) “these people vote”!

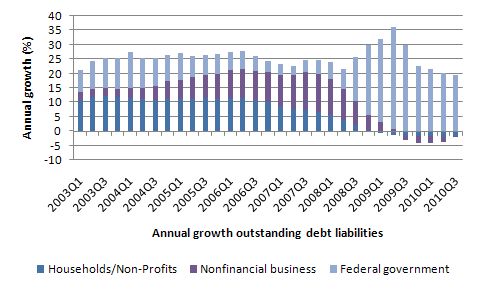

The next graph is drawn using the same data but just shows the annual growth in outstanding debt. Once again you should realise just what the US economy is having to deal with at present

Krugman then loses the plot in saying:

But wouldn’t it be expensive to have the government support the economy for years to come? Yes, it would – which is why the stimulus should be done well, getting as much bang for the buck as possible.

Exactly, why is a deficit “expensive”? All spending leads to real resource deployment. The only way we can consider “costs” is to assess the real resources that are being used to meet the spending. So yes net public spending “costs” the real resources that it brings into production.

But when the alternative is that these real resources would be languishing in unemployment or idle machines etc then the opportunity cost is very low indeed. It doesn’t take much productivity to be better than zero!

The rising debt levels and the interest payments are not costs that have any relevance. The debt levels just signify rising non-government wealth stored in that particular savings form and the interest payments are income. It never ceases to amaze me that the mainstream consider private wealth and income growth to be good but cannot get their heads around the fact that government bonds and the interest servicing associated with the bonds are also sources of private wealth and income (respectively).

Conclusion

I agree with Krugman that the net public spending should be carefully designed to ensure it maximises the employment potential and improves the lot of the disadvantaged above all else. But he is completely in the mainstream camp when he says thing like “the …[tax] … deal will cost a lot – adding more to federal debt than the original Obama stimulus – it’s likely to get very little bang for the buck.”

Yes, it might not maximise employment etc per dollar spent (or foregone) but the rise in debt is irrelevant to the assessment of the “cost”. In fact, in a sense (real terms), we actually should be extolling the virtues of very “costly” programs at present given the extent that productive capacity is being under-utilised around the world.

The more real resources that are tied up in fiscal programs the more quickly the world will recover and private spending resume.

That is enough for today!

An interesting paper has sprung up that shows how the various different monetary policy systems have affected the credit cycle.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/speeches/2010/speech463.pdf

pp28-29 have the graphs.

Deficit-doves are dangerous. They believe that when private spending is weak governments should run budget deficits but when growth returns the budget should go into offsetting surpluses and balance over the course of the business cycle. They argue that the mainstream approach to run budget surpluses or balanced budgets always provides no scope for government to counteract reductions in private spending and so such as strategy commits the economy to periods of recession and rising unemployment.

Far from being dangerous, that’s a very sensible policy, as it results in high growth, low inflation and a strong currency. Government money is spent efficiently, and it helps keep the economy afloat while the private sector deviates from its normal tendency to increase investment.

The intent of the mainstream (neo-liberals) is clear – it is an ideological dislike of government involvement in the “market” and so the fiscal rules aim to limit the socio-economic role of the state.

You’re making the mistake of assuming they all have the same motive. In reality it’s likely that many have completely different motives.

Deficit-doves think that deficits during period of growth are likely to “crowd out” private sector investment by competing for funds. However, this proposition really makes them part of the problem.

You know the phenomenon of crowding out is real even though it doesn’t happen the way most neoliberals think it does. Is the end result all that different?

Under what conditions would Paul Krugman advocate a reduction in stimulus and the deficit?

He may describe it as being ‘expensive’ yet it’s clear he believes it is worthwhile. Perhaps he recognizes that stimulus is ‘affordable’ until inflation returns. At that point, the mainstream perception of inflation as something undesirable must be addressed.

Joke of the day: Otmar Issing calls Euro bonds “undemocratic” because he believes they will cause transfer payments between Euro member states without letting tax payers have a say in it. The punchline: He is a former chief economist of the European Central Bank. I wonder whether he ever asked citizens whether they’re okay with the policies of that institution… (Source: http://bit.ly/ecAkvR – in German, sorry)

@Aidan: You might want to read up on some of the other articles on this blog. Bill’s point is that the government can only balance its deficit over the course of a business cycle if the private sector does not net save over the same time frame (if net exports are balanced). However, the private sector usually desires to net save in the long run, and so it makes no sense for government to try to balance its budget.

Also, perhaps you’re confusing two different usages of the term “crowding out” that Bill used in the article? The difference is crucial…

Mr. Krugman’s views on deficits change with administrations.

“Under what conditions would Paul Krugman advocate a reduction in stimulus and the deficit?”

If a republican is in office Krugman becomes a deficit-hawk and would warn against the dangers of deficits, as he did when Bush was in office.

In a 2003 column Mr. Krugman wrote:

“Two years ago the administration promised to run large surpluses. A year ago it said the deficit was only temporary. Now it says deficits don’t matter. But we’re looking at a fiscal crisis that will drive interest rates sky-high.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/11/opinion/11KRUG.html

A good rule of thumb is to try not to learn about economics from anyone who’s views on basic economics is politically-driven. Mr. Krugman writes a political blog and uses economics to support is ideology. Principles of basic economics do not change with administrations. Mr. Krugman writes an entertaining column but he has proven he cannot be taken seriously.

Dear Aidan,

You claim “….. as it results in high growth, low inflation and a strong currency. Government money is spent efficiently, and it helps keep the economy afloat while the private sector deviates from its normal tendency to increase investment.”

This is an assertion. Do you have the evidence – empirical data – to back this up? It would be great to see it.

cheers

Graham

Krugman is misleading here:

“The root of our current troubles lies in the debt American families ran up during the Bush-era housing bubble. Twenty years ago, the average American household’s debt was 83 percent of its income; by a decade ago, that had crept up to 92 percent; but by late 2007, debts were 130 percent of income.”

“All this borrowing took place both because banks had abandoned any notion of sound lending and because everyone assumed that house prices would never fall. And then the bubble burst”.

This “root of our current troubles” is presented backward here and this is typical of those trying not to offend the plutocrats. As Bernanke explained before a Congressional panel, and, as it has been made unquestionably clear by countless economists since then, the “root” of the problem was excess liquidity which was being fed by foreign inflows.

Many though started to realize that the Bush tax cuts had been made possible, during 2 wars, buy those same foreign inflows due to the Governments borrowing costs being so cheap at the time. And so it is interesting here that Krugman-the-China-blamer would downplay the role of the lenders by leading with the borrowers. This is disingenuous though because it is the lenders who decide who is worthy of what loans, and, the interest-rates were being held down by the foreign inflows. So it is less than forthright to ignore the foreign inflows, but, if those inflows are studied closely enough the fact that the Bush Administration was part of an ongoing effort to use dollar hegemony to manipulate the global economy in dubious ways is not hard to understand, and that effort had been ‘ongoing’ since the days of the Washington Consensus in the early ’90s. So, this is not something that can solely be blamed on the Republicans.

Basically, because the Chinese (and other nations) were taking in far more dollars than what were represented by their trade imbalance with the US, which made exchanging dollars for yuans a choice that would guarantee too much appreciation of the yuan, and because the US made it difficult for the Chinese (and other nations) to spend all of their their surplus dollars on anything other than T-bills, the US was tying up a substantial portion of global savings with deficit spending while the tax cuts allowed for increased capital formation for private sector investors. All very clever, and advantageous in competitive terms for US investors, but embarrassing if the “root” is followed down to its source of nourishment, where it becomes rather obvious that dollar hegemony-taken-too-far played an important role in the GFC. This also makes blaming China more than just difficult.

For Aidan @ 2:13

I don’t follow your point regarding crowding out. At full employment Bill notes that real resource ”crowding out” exists in that resources devoted to one endeavour cannot be devoted to another without subtracting from the first. At less than full employment, unemployed resources are available to be devoted to one endeavour without being subtracted from another since they are idle. Obviously regional and professional factors might blur this somewhat in practice but as a general statement I don’t understand your objection.

“At less than full employment, unemployed resources are available to be devoted to one endeavour without being subtracted from another since they are idle.”

I think part of the communications problems MMT advocates face is the perception that even though they acknowledge inflation as a real constraint on government spending, they believe the only resource that counts toward measuring that inflation constraint is labor. However, the stagflation era clearly showed that even if there are substantial labor resources sitting idle, government spending can still contribute to inflation if there are other binding resource constraints. This is why I have on several occasions asked about the MMT position on policies that target a specific price level besides the Job Guarantee and the more general fiscal adjustment reccomendations such as increasing taxes or decreasing spending. Things like Abba Lerner, David Colander, and William Vickrey’s Market Anti-Inflation Plan. So while it is true that policies like the Job Guarantee may be an excellent way to deal with the possible emergence of inflation in the labor market, there still needs to be a way to address inflation that emerges from a different market. Therefore, I’m definitely looking forward to Professor Mitchell’s promised blog on the MMT policy response to inflation derived from supply-side sources besides the labor market. IMHO, the web-based MMT presentations at least (I can’t claim to be too familiar with the more formal research at websites like CoFFE or the Levy Institute) need to do more to address these issues.

Bill, Basically I agree with you as usual. Just one quibble. In Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 (cited above) you mention the “target” rate of interest about ten times, without telling us what the objective of this rate is. Well the idea is in influence aggregate demand, is it not? I.e. low rates allegedly increase demand.

But since in the present environment we are trying to raise demand (certainly in the U.S.) what’s the point of having a rate that is anything other than zero?

In other words I agree with Randall Wray who suggested a couple of days ago that government should just stop issuing bonds, i.e. stop creating debt, and let the deficit accumulate as extra monetary base. See:

http://www.creditwritedowns.com/2010/12/qe2-stop-issuing-bonds.html

Warren Mosler made a similar suggestion – see 2nd last paragraph here:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/warren-mosler/proposals-for-the-banking_b_432105.html

I agree with the above two individuals. My preferred policy is to try to control demand by adjusting net spending (a la Abba Lerner). As to interest rates, let them look after themselves, i.e. let the market determine interest rates.

Dear Ralph (2010/12/15 at 9:09)

Isn’t that what I have consistently argued anyway?

Please see my blogs – The natural rate of interest is zero! and Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more explicit statements in this regard.

best wishes

bill

NKlein,

I think you are partly right… but also, the MMT makes the same mistake on the value of human capital that most other economic theory does. There is a basic assumption, which is central to Marginal Utility theory, that non-productive human capital and productive human capital are equal, but they clearly are not. A prison guard who earns the same income as a carpenter, for example, does not add to economic progress at all, the guard’s cost to society is in fact a negative, while the carpenter is unquestionably a positive, yet economists give each the same value in GDP terms. And as economies become increasingly service-based, this deceiving method of keeping score, deceives increasingly.

But it is not just human capital (time) that can deceive. For example, if two objects made from identical amounts of steel, with identical production costs as well, are compared, one of the units of steel being used to create a wrench, while the other unit is used to build an artillery shell, while the wrench might provide utility and therefore continually be a benefit to economic progress, the artillery shell may destroy a wrench factory, but of course economists give the wrench and the artillery shell the same credit toward GDP.

Not to suggest that the Labor Theory of Value may be any less deceptive, but instead to say that many ‘grains of salt’ are needed.

@Nicolai Hähnle:

@Aidan: You might want to read up on some of the other articles on this blog. Bill’s point is that the government can only balance its deficit over the course of a business cycle if the private sector does not net save over the same time frame (if net exports are balanced).

Bill is basically correct, although foreign investment and the carry trade do complicate it a bit. And I’ve been reading this blog for most of this year.

However, the private sector usually desires to net save in the long run, and so it makes no sense for government to try to balance its budget.

Bill has frequently made this extraordinary claim, but has not supplied extraordinary proof – or indeed any proof.

Most people, and some businesses, desire to pay off their debt, but this is balanced by more of them going into debt and taking on more debt to expand.

Eventually interest rate rises are usually used to dissuade the private sector from taking on more debts and the economy goes into recession. That’s the way the business cycle normally works – the private sector don’t desire to net save at all, but sometimes the central bank forces it in that direction.

Also, perhaps you’re confusing two different usages of the term “crowding out” that Bill used in the article? The difference is crucial…

It’s not that I’m confusing them, it’s that I’m asking what the implications of the difference are in practice between them and also the third kind of crowding out where an inflation-targetting central bank sees the growth in demand and decides to put up interest rates?

“Bill has frequently made this extraordinary claim, but has not supplied extraordinary proof – or indeed any proof.”

I would say it is a matter of basic mathematics Aidan. For every $100 a government spends it must always get $100 back in tax for any positive tax rate if everybody spends everything they earn instantly. The bouncing of the money around the economy on various transactions would ensure that.

Therefore if the money isn’t consumed entirely by taxation somebody outside the government sector didn’t spend all the currency injected. And the reason for that in my view is that banks are not 100% efficient at redistributing stocked currency into the spending stream. Right at the moment they are not doing their job very well at all and net-savings of currency in the private sector are piling up.

You only have to look at the National accounts to see how it works.

Arguably even if the banks had crystal ball efficiency the fractional reserve rules prevent banks from full recycling and therefore some currency must always be held back by the banks. That will show up as private sector net-saving.

“Eventually interest rate rises are usually used to dissuade the private sector from taking on more debts”

Again the evidence is that doesn’t happen. Raising interest rates does not appear to dissuade people from taking on debt. If you map the change in interest rates against the change in total debt owed (For the US that is FEDFUNDS against TCDMO) then there is no correlation.

In real terms, it doesn’t take much productivity to be better than zero. But there are additional costs, other than real resource costs.

The way I view Keynesian effects is that they describe purely financial problems, not “real resource” problems. If you were to just look at the behavior of the economy, without looking at prices or balance sheets, you would not suspect anything wrong prior to 2008. Perhaps a bit too many people engaged in housing, but not so much. But there were financial problems with the economy, in that households were paid too little and were spending too much. Prices were too high, and now there are deflationary pressures that are spilling over to real resources being unemployed.

OK, if you believe all of that — that the current problem is not structural unemployment, but a financial problem — then it becomes important that you do not distort relative prices away from sustainable levels. And that means that there are other costs, other than real resource costs, that the government needs to be concerned about. In many ways, concerns about government debt levels are about these financial costs.

You cannot just step back and say “we have 10 unsold cars just sitting in the parking lot. It’s a waste to not buy the cars and give them to those who want cars. After all, money is free for the government”. The problem is that money is not free for the private sector. The private sector has to find some way to transact so that prices clear.

The 10 customers who want to buy the cars aren’t buying them because they are too expensive. Equivalently, their wages are too low in terms of cars, and they are no longer willing to go into debt to buy the overpriced cars.

There is a battle of wills between the workers refusing to shop, and the firms refusing to lower prices or increase the wages of their employees.

If the government intervenes on behalf of the firm and buys the unwanted output, then the price adjustment doesn’t occur. The result is that, for the individual, goods will continue to be too expensive and each individual will become dependent on government support in order to be able to buy goods. As soon as the government withdraws fiscal support, then because goods remain too expensive, the recession will resume. This is an example of an economy on permanent life-support.

This does not mean that the government should do nothing, or should not engage in costly fiscal spending. It should buy the cars, or supply enough income to the unemployed to buy the car. But at the same time, it should tax any additional earnings arising from this intervention away from the firm’s shareholders, so that the after tax return on capital is the same as if the firm would have lowered prices and allowed the market to clear. At least this way, the government is interfering less in the price adjustment process, so at least the cost of capital continues to fall to some sustainable level, rather than being propped up by deficit spending.

At least, it’s something to keep in mind — there are financial costs, in terms of disequilibrium prices, that are not measurable in terms of real resource costs.

@graham says:

Dear Aidan,

You claim “….. as it results in high growth, low inflation and a strong currency. Government money is spent efficiently, and it helps keep the economy afloat while the private sector deviates from its normal tendency to increase investment.”

This is an assertion. Do you have the evidence – empirical data – to back this up? It would be great to see it.

Unfortunately I’m not aware of any government that has behaved countercyclically. Australia came close (more by accident than by design) and is doing pretty well, but the basis for my assertion is only theoretical.

Public money is spent more efficiently when there’s not much competition for resources from the private sector. Likewise private money is spent more efficiently when there’s not much competition from the public sector. The currency’s usually higher when the government has a balanced budget because it means money supply’s not increasing faster than commercial demand. And because the currency’s strong and demand relatively stable, inflation is likely to be low.

Question for the board ( a little off topic)

What do you make of claims that Consumption has returned to precrisis levels (in the US) http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/PCECC96?cid=110 Govt spending has increased http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/GCEC1?cid=107 but private investment has fallen http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/GPDIC1?cid=112.

This guy is using this data as evidence that its not an aggregate demand problem related to consumer spending but at the private investment level only. There must be something missing in this data. No way that 8 million people earning significantly less can be consuming at same level and it is unikley that the rest of us have made up all their shortfall, otherwise sales wouldnt be down…..right? What is missing in this guys analysis? I’d like to respond to him but I’m not sure where to attack his argument.

Here is his entire post

http://crankyprofj.blogspot.com/2010/12/deficient-demand-and-demand-for-labor.html

Thanks

After reading what Paul Krugman wrote in 2003, I will no longer be following his column. I was unaware that his views were that inconsistent.

Neil Wilson says:

Wednesday, December 15, 2010 at 14:30

“Bill has frequently made this extraordinary claim, but has not supplied extraordinary proof – or indeed any proof.”

I would say it is a matter of basic mathematics Aidan. For every $100 a government spends it must always get $100 back in tax for any positive tax rate if everybody spends everything they earn instantly. The bouncing of the money around the economy on various transactions would ensure that.

I’m surprised you’re making such silly claims! Firstly this has nothing at all to do with reality, and secondly it’s logically false anyway because some of the money will be spent on imports.

Therefore if the money isn’t consumed entirely by taxation somebody outside the government sector didn’t spend all the currency injected. And the reason for that in my view is that banks are not 100% efficient at redistributing stocked currency into the spending stream. Right at the moment they are not doing their job very well at all and net-savings of currency in the private sector are piling up.

You’re confusing saving and net saving. Savings pile up, but that tells us nothing about what happens to net savings (defined as savings minus investments).

You only have to look at the National accounts to see how it works.

Arguably even if the banks had crystal ball efficiency the fractional reserve rules prevent banks from full recycling and therefore some currency must always be held back by the banks. That will show up as private sector net-saving.

No it won’t. Firstly the reserves don’t all have to be held as cash – liquid assets will do. Secondly it says nothing about how much the banks have borrowed from the Central Bank. Bill’s already supplied evidence that they’re not reserve constrained.

“Eventually interest rate rises are usually used to dissuade the private sector from taking on more debts”

Again the evidence is that doesn’t happen. Raising interest rates does not appear to dissuade people from taking on debt. If you map the change in interest rates against the change in total debt owed (For the US that is FEDFUNDS against TCDMO) then there is no correlation.

If you can’t find a correlation in the statistics then I suggest you stop relying on statistical correlations to see what’s going on – for this is the main reason interest rates are adjusted!

People tend to buy the most expensive house they can afford, so when interest rates are lower they can afford more and take out a bigger loan. For businesses it’s different – the cost of equipment means it’s likely to be an all or nothing situation. New equipment may be worth borrowing for at 5% interest, but at 10% interest the do nothing option is preferable.

Aidan,

“I’m surprised you’re making such silly claims! Firstly this has nothing at all to do with reality, and secondly it’s logically false anyway because some of the money will be spent on imports.”

I don’t think I’m the one making silly claims. Whether the money ends up with a national or foreign name on it is irrelevant. Ultimately only the name changes on the currency at the central bank. Currency is either spent in the currency zone and taxed away or it is net-saved in that currency zone within any particular accounting period

Therefore the mathematics holds. The existence of the deficit is prima facie evidence of net-savings by the non-government sector.

@Neil Wilson

I don’t think I’m the one making silly claims. Whether the money ends up with a national or foreign name on it is irrelevant.

On the contrary, when considering sectoral balances it’s crucial. Money spent on imports is money the private domestic sector can’t save.

Ultimately only the name changes on the currency at the central bank. Currency is either spent in the currency zone and taxed away or it is net-saved in that currency zone within any particular accounting period

Therefore the mathematics holds. The existence of the deficit is prima facie evidence of net-savings by the non-government sector.

‘Tis easy to reach the wrong conclusion if you only go by prima facie evidence. You’re also not taking into account the original source of the money. It usually comes into existence when the central bank loans it to a commercial bank. This means it’s 100% debt, so the amount saved can’t exceed the amount borrowed

The desire by the private sector to borrow far exceeds its desire to save, particularly in good economic conditions.

Greg,

I don’t see the contradiction. Personal consumption needs to increase every year, as does output, otherwise the economy is going to be in a recession.

* We have a growing labor force

* We all have savings in the forms of bonds/stocks that must be repaid with interest

* There is growing productivity per person, so a constant level of purchases combined with growing output/employee means either deflation or unemployment.

So the statement that expenditures have “recovered” to the level of the past doesn’t mean that the economy has recovered, because we need growth, not a constant level. Personal consumption expenditures need to be 9% higher than they were 3 years ago, if the economy is to grow at 3% per year, in real terms. That means a demand gap of 9%. This is pretty close to the unemployment level.

Now if the economy does not grow at 3% but stagnates or grows at 1%, then all those firms that took on debts promising returns of 3% are going to be in a bind. All the households that took on mortgages will also be in a bind. Pension funds assuming a certain return will be in a bind; everyone will be in a bind, not to mention the unemployed who will not be hired unless there is demand for their services.

“We all have savings in the forms of bonds/stocks that must be repaid with interest”

They don’t have to be repaid with interest. That is a social convention. There is an argument that simply having the stock available to you and nobody else is social reward enough.