The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The Euro bosses ignore all the lessons

I was thinking about the recent European Council meeting today which was held in Brussels over the weekend. It is clear that the Eurozone bosses are choosing to ignore all the lessons that the current crisis has provided to them about the basic design flaws of their monetary system. They think the solution to their problems is to make it even harder for member governments to provide net spending to their economies at times of stress. They fail to articulate the most basic macroeconomic fact that confronts them – unemployment is rising across the zone and production generally is stagnant because there is not enough demand for sales of goods and services. If the private sector won’t provide that demand then the government sector has to given that they cannot rely on net exports to cure the deficiency. By deliberately restricting governments and effectively forcing them to engage in pro-cyclical fiscal responses the Euro bosses are not only prolonging the agony the citizens are facing but are also engaging in a self-defeating strategy. As we are seeing budget deficits are rising as austerity is imposed. The solution to the Eurozone problems is to disband the zone and restore individual currency sovereignty at the national level. It would be painful to do that but in the medium- to long-term it will be less painful than the trajectory they are following.

The recent developments in the Eurozone are pretty depressing.

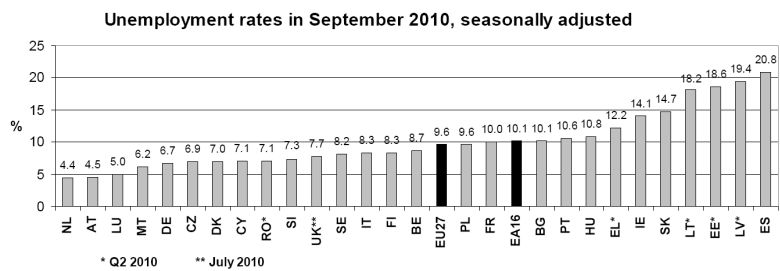

As I reported yesterday, Eurostat (October 28, 2010) released their latest – Labour Force data – which shows that unemployment continues to rise and is now above 10 per cent.

The Report says that there are:

… 23.109 million men and women in the EU27, of whom 15.917 million were in the euro area, were unemployed in September 2010. Compared with August, the number of persons unemployed increased by 71000 in the EU27 and by 67000 in the euro area. Compared with September 2009, unemployment rose by 0.656 million in the EU27 and by 0.424 million in the euro area.

The following graph is taken from Eurostat’s publication and shows the distribution of unemployment rates across the EU. Note those out to the right.

So this is a system that knows how to get the potential out of its workforce!

Further, Eurostat report (October 28, 2010) that – Quarterly Sector Accounts – for the second-quarter that household saving ratios and real household disposable income continue to fall in the Euro area. This is not the sign of a healthy economic block.

Eurostat also published their latest Government deficit and debt figures for 2009 on October 22, 2010. If you examine it closely you will see that the nations that have already adopted austerity saw expanding deficits in 2009 contrary to their plans. The nations with very large changes in their fiscal positions (larger deficit to GDP ratios) are typically those out to the right of the unemployment rate graph above.

The Euro wannabees like Estonia and Latvia are particularly problematic and their governments have lost the plot with respect to maximising the potential of their citizens. The politicians seem content to trash the living standards of their citizens so they can get to more sumptuous dinners down at Brussels.

But the increases in deficits etc just tell me that the automatic stabilisers were working hard to provide some fiscal support for their economies as private spending continued to collapse and discretionary net spending by the governments fell. The reaction of the budget bottom line is totally predictable and to think otherwise reflects a total ideological blindness.

The governments knew it too but lied. They are trying to “finish” off the neo-liberal smashing of the welfare state and taking this opportunity to do it under cover of a crisis.

As an aside, the 2009 data for the UK shows a deficit equal to 11.4 per cent of GDP. This will rise as its austerity programs undermine growth and drive the automatic stabilisers into providing more fiscal support for the economy.

That is all background to the latest “reform” proposals from the EU bosses.

The Economist Magazine reporting from Brussels (October 28, 2010) where the European Council meeting was held conclude that the result is – Game, set and match to Angela.

You can read the full concluding statement of the EU Council meeting HERE.

The Council conclusions were (chopped up a bit to save space):

- “The European Council endorses the report of the Task Force on economic governance. Its implementation will allow us to increase fiscal discipline, broaden economic surveillance, deepen coordination, and set up a robust framework for crisis management and stronger institutions.”

- “speed up work on how the impact of pension reform”.

- “establish a permanent crisis mechanism to safeguard the financial stability of the euro area as a whole … [and implement] … a limited treaty change required to that effect, not modifying article 125 TFEU (“no bail-out” clause).”

- “to ensure that spending at the European level can make an appropriate contribution to … fiscal discipline … to bring deficit and debt onto a more sustainable path”

- A note to support the G20 “Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth, notably concerning fiscal consolidation plans, financial regulatory reform, social cohesion, job creation and the need for further structural reforms”.

- A note to broaden the IMF membership etc as agreed by the G20 meeting in Seoul.

- Some generalised motherhood statement about climate change.

So they plan to set up a bail-out fund but not call it that and force stringent anti-people rules and conditions on any nation that dares to access it. Apparently they are going to include an “exceptional circumstances” clause thus recognising that the design of their monetary system is incapable of actually dealing with the flux and uncertainty of aggregate spending.

But instead of abandoning the system or putting the capacity in place to deal with asymmetric demand shocks (that is, a unified fiscal authority) the European Council just introduced measures which will make the situation worse both in the short-run (getting out of the current mess) and in the medium-term, when the next negative demand shock arrives.

They EU plans to impose harsher fiscal discipline on governments without questioning the nature of the cyclical effects on the state of member nation budgets. In other words, they will force pro-cyclical discretionary fiscal responses from government when they are beset with a major negative demand shock.

And … meanwhile … to the East a bit, the European Central Bank will continue bailing the whole show out (so far more than 60 billion euros in purchases) with its treaty violating “fiscal policy” purchases of government debt in the secondary markets. As long as the ECB continue buying the debt that the bond traders are avoiding at lower yields the Eurozone will stumble along mostly in a state of near recession.

The Euro bosses can then attend their sumptuous councils and summits and wine and dine to their hearts content dreaming up ridiculous “reforms” to their sinking ship. None of these reforms will help their system if the ECB curtail their “fiscal spending” policy.

It is hard to believe these characters are taken seriously. How did they get into leadership positions? More on that later.

Inflation-obsessed Germany has been pushing hard to introduce even harsher fiscal rules than are already in place in the Eurozone in the face of general opposition from the other member states. So the fact that the European Council went along with Germany’s wishes is the context in which the Economist considers Angela won the tennis match.

If only it was a game!

The Germans only partially “won” though. They actually had been pushing to take voting rights off nations who violated their (stupid) fiscal rules. The Economist points out that this would have led Ireland to call a referendum about the reforms, which, given the state of the place and the voter anger, would have been lost. So either by default or the people rightfully jacking up – the Eurozone would have started to crumble … as it should.

Earlier, on September 23, 2010, the Economist Magazine ran a story – How to run the euro – Fixing Europe’s single currency – where they laid out what they considered to be the blueprint for an efficient solution to the current issues facing the EMU countries.

In referring to the creation of the euro bailout fund (the legality of which is about to be challenged in a German court) and the fact that the ECB has been “funding” several governments as their deficits worsen because they are imposing austerity on their citizens, the Economist said:

These efforts have staved off the sense of emergency, but the euro zone’s underlying problems are not easily fixed.

The temporary measures do not amount to palliative care which generally tries to ease the pain of the patient while they die. In the Eurozone case, the patients – and it is a ward full of sick nations – are being kept alive but the quacks are still forcing deep pain on them.

The situation is getting ridiculous. The Euro statisticians are currently debating whether the Irish bailout of the state-owned Anglo-Irish Bank which is on the verge of collapse should be included as Government’s discretionary spending. At present, the Irish budget deficit is rising (and is around 12 per cent of GDP). This is generating even more shrill calls from the Euro bosses to cut back further.

But if the bank bailout is included then the the budget deficit will jump to over 20 per cent of GDP and you can imagine what the Brussel-Frankfurt bullies will be saying next. It is sheer idiocy.

In the European Council document I did not see one reference to the fact that the Eurozone fails all the basic tests of an optimal currency area (OCA). This concept was used way back to “justify” the decision to create the common currency although all the decision-makers at the time clearly would have realised the conditions for an OCA were absent.

It was just another case of hiding behind some arcane economic theory to implement a political agenda.

But at present the EMU zone looks less like an OCA than ever before. Some of the big member states (Germany, Netherlands, and Austria) are riding a manufacturing wave (which is about to break and dump them) while the southern states are in continued recession and likely to deteriorate in real terms even further.

The European Council makes no reference to these widening disparities and the fact that some of the member states are in impossible situations. It clearly wants to deny that there is no coherent basis for the monetary union.

Economists developed the concept of an Optimal Currency Area (OCA) in the 1960s although it was always a dodgy case of textbook theory, inapplicable to the real world, being applied to suit ideological ambitions.

Three essential conditions have to exist to justify the formation of a monetary union as an OCA:

- The countries should face common consequences if hit by a negative shock (no asymmetric shocks). So, for example, unemployment rates should be similar across the countries in the union;

- There should be a high degree of labour mobility and/or wage flexibility within the group of countries.

- There is a common fiscal policy that can transfer resources from better performing to poorly performing countries.

Yes, the EMU should disband immediately using these “theoretical conditions” if they are still claiming it to be an OCA.

You might like to compare this list of “theoretical conditions” with what emerged out of the Maastricht treaty which stipulated five conditions: convergence in interest rates, budget deficits, public debt, inflation rates and stable exchange rates prior to the formation of the union.

These conditions are not remotely like those that were used to define an OCA and reflect more the blind neo-liberal ideology that was gathering pace at the time and was dominating policy makers.

The point is that the EMU countries did not (and do not) satisfy the criteria for an OCA yet they still went ahead with the common currency which meant that each sovereign nation gave up their monetary policy independence and allowed the Stability and Growth Pact to hamstring their fiscal sovereignty.

The ability to absorb external shocks is very different across the Eurozone countries. The stronger industrial countries like Germany (who has a huge external surplus) as do the Netherlands, are in totally different situations to the capital importers such as Spain. The stronger nations can absorb shocks much better than Spain.

Finland, for example retains close cultural and trading ties to Norway and is not linked much in trade with Spain. Ireland maintained strong trading relationships with the UK and less with continental Europe.

The labour mobility criteria is required because if unemployment rises in one country, the workers are able to move within the union to find other work. Given that national identities are still strong in Europe, labour mobility is relatively low.

One of the interesting side effects of the coincidence of a major real crisis and a housing collapse is that labour mobility is now reduced (in all countries).

In bad times, those that can move tend to move to chase job opportunities elsewhere. However, when there is a major real estate collapse this mobility doesn’t occur as significantly because people cannot afford to move – especially those with negative equity in their residences.

You might get mobility (according to the theory of an OCA) if there was wage flexibility across the union. So workers in recessed regions would reduce their wage demands and make it easier for firms to hire them. Allegedly, this would also lower prices of final goods and services produced in that region which improves their competitiveness.

So while the EMU is really a fixed exchange rate system imposed on a number of countries and so nominal exchange rate depreciation cannot occur, real terms of trade changes can happen if relative unit labour costs change.

This is how the “textbook” theory claimed it would work. The recessed nations could improve their competitive by cutting wages and unit labour costs (a real rather than a nominal depreciation) which would attract firms into that region away from other regions in the union.

Of-course, this assumes that employment is driven by wage levels. If a nation such as Spain tried to cut real wages (engineering this would be difficult in itself) then there would be a huge drop in demand by Spanish workers. It is highly unlikely that the so-called “real depreciation” impacts would offset the local income effects on demand.

One of the other constraints on mobility is that the EMU did not develop a common language. Workers are thus disadvantaged when they move into a different language zone.

There is very little wage flexibility across the European economies (which is a good thing) but hardly consistent with the OCA criteria. Unions still play significant roles in wage determination and resist nominal wage cuts, especially in times of hardship.

But Germany also made sure that these “competitive” effects would not occur. They were aggressive in implementing their so-called “Hartz package of welfare reforms”. The Hartz reforms were the exemplar of the neo-liberal approach to labour market deregulation. They were an integral part of the German government’s “Agenda 2010?.

The Hartz process was broadly in-line with reforms that have been pursued in other industrialised countries, following the OECD’s Job Study in 1994; a focus on supply side measures and privatisation of public employment agencies to reduce unemployment. The underlying claim was that unemployment was a supply-side problem rather than a systemic failure of the economy to produce enough jobs.

The reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market (so-called mini/midi jobs) and there was a sharp fall in regular employment after the introduction of the Hartz reforms.

The German approach had overtones of the old canard of a federal system – “smokestack chasing”. One of the problems that federal systems can encounter is disparate regional development (in states or sub-state regions). A typical issue that arose as countries engaged in the strong growth period after World War 2 was the tax and other concession that states in various countries offered business firms in return for location.

There is a large literature which shows how this practice not only undermines the welfare of other regions in the federal system but also compromise the position of the state doing the “chasing”.

In the current context, the way in which the Germans pursued the Hartz reforms not only meant that they were undermining the welfare of the other EMU nations but also drove the living standards of German workers down.

Further, the OCA concept required that there be a union-wide fiscal capacity to maintain uniformity of outcomes within the nations that made up the monetary union in the face of demand shocks.

The design of the Eurozone deliberately prohibited such a capacity being established. An OCA clearly requires a single fiscal authority that can transfer net spending from one region to another to even out economic performance. This criteria is absolutely essential in defining a theoretical OCA.

However, the real politik that led up to the creation of the EMU was not even remotely consistent with the criteria. Germany (and to a lesser extent France) were paranoid about the possibility that some of its southern neighbours (Italy and Spain) would use fiscal policy in an irresponsible manner. This led to the prohibitive clauses in the Growth and Stability Pact that force all EMU members to limit their budget deficits to 3 per cent of GDP or face penalties.

If the EMU countries were serious about creating conditions consistent with an OCA they would have handed over their fiscal powers to the European Parliament. But the European Council’s latest intent – to make the SGP rules even more stringent and to enforce them more closely is exactly the opposite to what is required. The decision is just making the design flaw even more glaring.

The logic of the Euro bosses was this – they had to severely constrain fiscal policy because they believed that if say, Italy spent up this would cause inflation and the ECB would “have” to (as if they have no choice) increase interest rates for all nations and damage growth generally.

The other opinion on this reflected Germany’s inflation obsession. They considered the ECB would start “printing money” to fund the deficits and this would cause inflation or that the Germans would have to raise taxes to bail out Greece or Italy or some other nation without the Teutonic discipline.

However, the resulting design provided no sensible capacity to deal with the negative demand shock that came along with the GFC. The automatic stabiliser impacts drove budgets outside of the rules quite apart from any discretionary changes in government fiscal policy.

Spain was an exemplar of Euro fiscal discipline and is now staring at more than 20 per cent unemployment, an impending collapse of its banking system and nowhere to turn.

It is mindless to design a monetary system and impose rules whereby the normal operations of the automatic stabilisers force a nation to violate those rules. It is even more mindless to then turn on that nation and impose pro-cyclical policies which further damage the welfare of the citizens.

The Economist Magazine says:

The euro allowed these internal imbalances to grow unchecked and now stands in the way of a speedy adjustment, because euro-area countries whose wages are out of whack with their peers’ cannot devalue. For critics of the euro this only points up how far the zone is from being an “optimal currency area”. America’s regional economies may often diverge: a drop in oil prices might prompt a consumer boom in California while leaving Texas depressed. But wages and prices are far more flexible in America and workers have generally been more inclined to move from state to state to find work. By contrast, say the sceptics, the economies of the euro area are too diverse to live with the same money and too inflexible to adjust to imbalances when they arise.

And moreover, the US government provides strong fiscal transfers to the states that are triggered in times of need. They are not sufficient and in the current context need to be much larger but the fact is that the US system has a central fiscal capacity which is absent in the design of the EMU and is only operating at present – and outside of the rules – courtesy of the ECB “fiscal” actions.

The Economist, however, doesn’t get it. They claim that:

The euro’s weaknesses can, with difficulty, be addressed and measures can be put in place that should at least mitigate the build-up of similar problems in future. The zone’s woes are not unique. Few single countries would meet the academic criteria for optimal currency areas. America has its share of depressed spots-and since almost a quarter of those with mortgages owe more than their houses are worth, America’s workers are less mobile than they were. Nor is the euro wholly to blame for the credit booms in parts of the zone. Low interest rates and an underpricing of risk were widespread: credit boomed in many countries-America, Britain, Iceland-with floating exchange rates.

The only reason why American states are in as much trouble as some of the EMU states or that Britain and Iceland are suffering can be traced to a common problem – an inadequate fiscal response. However, that is where the comparison ends. Member states in the EMU are not sovereign whereas the US, Iceland and the UK governments remain sovereign in their own currencies.

In the EMU, there will typically be an inadequate fiscal response by construction. That is the design flaw that makes the whole system dysfunctional and the current ECB actions ad hoc to say the least. Necessary but totally arbitrary and in defiance of the logic of the system.

In the case of the US, Iceland and Britain the pain is totally voluntary – their respective governments refuse to use the fiscal capacity they have as sovereign nations.

But reflecting how misguided the Economist Magazine usually is, they argue, under the heading “the fiscal fix is in”:

New rules to encourage fiscal discipline should help the euro area. They will reassure the bond-market vigilantes-and should come in handy if the vigilantes drop off again. Now would be a good time for national governments to adopt home-grown fiscal rules, as Germany already has. And as euro members are to underwrite each other’s debts through the EFSF, it is natural that they should demand more say in each other’s budgets. European reviews of national budgets for the coming years have already been brought forward by six months. Firmer sanctions, such as withholding of EU funds or suspending members’ voting rights in the euro group, may be considered, but they would be politically fraught.

But reflecting how misguided the Economist Magazine usually is, they argue, under the heading “the fiscal fix is in”:

New rules to encourage fiscal discipline should help the euro area. They will reassure the bond-market vigilantes-and should come in handy if the vigilantes drop off again. Now would be a good time for national governments to adopt home-grown fiscal rules, as Germany already has. And as euro members are to underwrite each other’s debts through the EFSF, it is natural that they should demand more say in each other’s budgets. European reviews of national budgets for the coming years have already been brought forward by six months. Firmer sanctions, such as withholding of EU funds or suspending members’ voting rights in the euro group, may be considered, but they would be politically fraught.

You might like to read this blog – Fiscal rules going mad … – where I outline the recent constitutional developments in Germany that aimed to outlaw budget deficits in the coming years.

I repeat my earlier point – if the normal operations of the automatic stabilisers violate the rules (when there is a severe negative demand shock) and the stricter imposition of these rules will force even harsher pro-cyclical policy responses – then the system is flawed at the most elemental level. Imposing even harsher rules just exacerbate that situation.

What this proposal for increased “governance” is really about is making sure they don’t get embarrassed again by nations that breach their ridiculous fiscal rules. They are prepared to impoverish millions of European citizens just so they can hang onto some ill-conceived neo-liberal rules that make no sense in a complex economic world subject to major demand and supply shocks – which, in turn, are asymmetric in their regional impacts.

Given the diversity of the EMU member nations this asymmetry is lethal to the weaker nations. It beggars belief that the citizenry in those weaker countries would ever tolerate this entrenched austerity for very long.

What benefits do the workers in these nations gain from being subjected to a significantly higher risk of unemployment, declining real wages and working conditions; and diminished access to public infrastructure?

It is clear that the Eurozone leaders haven’t really learned anything from the crisis at all. Their system has failed to meet the first crisis it faced. Some might say that it succeeded because no government has defaulted. But that is only courtesy of the ECB “fiscal” operations disguising the design flaws. Overall, the Euro bosses have breached the strict intent of the “no bailout” rules.

Further, the only sustained fiscal response to the crisis by the EMU has been to pressure member governments to employ pro-cyclical policies to get back within the “rules” even though the rise in the budget deficits was driven significantly by the automatic stabilisers. Pro-cyclical fiscal policy is the exemplar of bad policy practice and defies the concept of sustainable fiscal intervention.

There are only two ways out: (a) disband the system; or (b) create a central fiscal authority.

The Economist magazine addressed the second option. After noting some advantages (“cheaper and more efficient to raise taxes centrally”; “cheaper to borrow” (not that a sovereign fiscal authority has to borrow); etc, they reject the idea because:

A country with high unemployment, say, would have less incentive to make its labour market more supple if jobless benefits were financed federally. Anyway, European countries are nowhere near ready to cede so much fiscal autonomy.

QED! The design flaw will persist and the policy initiatives being considered will entrench them and make outcomes when the next negative shock hits even worse.

All the rest of the proposals that the Economist Magazine considers relating to increasing international competitiveness (for example, to force Germany as a trade surplus nation to spend more domestically) will fail. But nations are already being bullied into cutting wages and conditions in a vein attempt to become more export-oriented.

Please read my blogs – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – and Export-led growth strategies will fail – for more discussion on why those policy options are deeply flawed.

Conclusion

If I lived in Europe right now I would be consulting immigration rules and heading to Australia. Apart from the weather being better at least our government saw fit to introduce strong and early fiscal interventions to quell the worst of the crisis. We are far from being Shangri-La but by comparison some of the Euro nations are becoming hell on earth.

All the policy initiative of the European Council will work to make the situation in Europe even worse and do nothing to address the fundamental design flaw in their monetary system which reflects the dictates of the prevailing neo-liberal logic.

To review the key blogs I have written about the EMU and its failings – the following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

- EMU posturing provides no durable solution

RBA puts rates up again

Apart from the bank economists getting it wrong again (I joined them this time!) today’s decision by the RBA to lift interest rates even though by their own admission there is a benign inflation environment at present is mindless. I will address the logic tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

I have been talking to a poster over at Steve Keens Talk Finance about FRB. You say “The way banks actually operate is to seek to attract credit-worthy customers to which they can loan funds to and thereby make profit. These loans are made independent of their reserve positions.” You are right and you are wrong there. Banks dont lend funds. They promise funds if you want them. And because you our your counterparty might want funds rather than ious then the bank must be mindful of its reserve positions.

Each large bank has a few hundred million in cash as a float in the branches, where cash and reserves are both central bank money and where cash can be sold to another bank for reserves. Each day a bank has to know what its reserve position is likely to be so it can get cash if it needs it to maintain the branch float. You simply cannot say that lending can happen independant of the reserve position. Banks already operate on the smell of an oily rag. They cant regularly totally run out of cash or confidance would evaporate. If a large bank usually only lends a few hundred million max without arranging finance in advance (new deposits for the larger loans) then the branch float alone enables money multiplier to be correct for those lending instances.

Money multiplier theory while fundamentally wrong does fit many aspects of banking accurately that can be *misunderstood* by people who imagine banks create money only via a stroke of a pen rather than with the reality they need creditors to create **spendable money** – otherwise the money is destroyed and there is no bank credit remaining and actual cash/reserves is supplied or interbank loans are made.

Now way! Just last week our national oracle of truth – tabloid BILD – ran a big headline on page one citing colleague economist Hans-Werner Sinn. The next 10 to 15 years will be very good years in economic terms. Germany will have 10-15 Golden Years. What BILD and Hans-Werner Sinn says is TRUE by definition. QED.

PS: I will take the liberty and forward above quote to my Austrian government. They will be delighted to hear that from an Australian perspective Austria is a big member state of the European Union 😉

Andrew,

The fallacy of the money multiplier occurs at two levels.

The first level is macro, which means the level of the banking system. The central bank always makes reserves available to the banking system as a whole such that reserve funds will trade at the target overnight night. That means that sufficient reserves are always available in proportion to the specified reserve requirements for individual banks. And the central bank supplies any increase in required system reserves when such requirement takes effect – which is following the corresponding deposit expansion. This allows the banking system to expand its loans and deposits without the central bank having supplied any new reserves beforehand. I.e. the central bank supplies reserves at the macro level after the deposits that give rise to the requirement have been created. Conversely, the banking system actually lends on the basis of credit demand and its own capital position, independent of any macro pre-supply of reserves. Capital is required to support risk taking of all sorts. New capital (or unutilized capital) is required to support risk and lending expansion; new system reserves aren’t.

The second level is micro, which means the level of the individual bank. Individual banks require reserves to make payments for all matter of transactions, including lending. An individual bank must square its reserve position on any given day. If it makes a new loan, and the borrower moves his funds to another bank, the lending bank can attract the reserves it needs to square its position in a variety of ways, including attracting new deposits. But the point is that those reserves already exist at the system level. If the lending bank is healthy, it will be able to attract them, because if that doesn’t occur, some other bank will end up with an excess reserve position, which is typically uneconomic. A banking system that is functioning effectively in its micro parts will accommodate any redistribution of reserves that is required for individual banks to square their positions each day. And the central bank is always available for LLR support if there are hiccups. Finally, individual banks run according to their own liquidity management policies in order to keep their own participation orderly – e.g. liquid asset positions, avoiding concentrated short funding exposures, etc. etc. I think this is the kind of thing you refer to in your comment, effectively.

The MMT debunking of the multiplier fallacy doesn’t claim that micro redistribution of the existing macro reserve supply doesn’t occur or isn’t required – that would be absurd, of course. That sort of thing is happening everyday for all sorts of reasons. What MMT claims and what is absolutely true is that the banking system in total doesn’t require new reserves before it lends. By implication that means individual banks don’t require new macro supply or their own share of new supply in order to lend. What individual banks require is their own functioning liquidity management systems that allow them to source reserve payments through the interbank payment system as needed – from the existing macro supply of reserves.

Defenders of the multiplier theory, when first knocked to the mat, sometimes get up and say that the multiplier theory is true, ex post. Well, if that’s what its creators meant, they wouldn’t have called it the multiplier theory. They’d have called it the ratio theory – in honour of those who have operational difficulty with the manipulation of numerators and denominators. The multiplier theory asserts in textbooks still that the central bank supplies macro level reserves before hand in order for banks collectively and individually to propagate lending. One chronic result of that nonsense is the existence of a host of monetarist blogs who continue to promote that false theory, while puzzling over what’s happened to their precious multiplier mechanism as the Fed has piled up $ 1 trillion in excess reserves for entirely different reasons. MMT just looks operational reality in the face, and explains it properly.

Andrew

Have you checked out the RBA financial aggregate data and its balance sheet? There is only approx. $47bn in cash on issue, out of a $1.2trn in broad money. Over $150bn a day is settled between the banks. Therefore, actual cash is immaterial in our monetary system.

The banks have a fair idea what reserves they need everyday for settlement based on experience. The RBA is estimates each day what shortage/surplus it expects to be in the system. If bank is short then it can sell government bonds/bills (fed and state), debt securities or USD outright or they can can repo them (sell with a side contract to repurchase them back from the RBA at set price) to obtain the necessary reserves. If they have surplus reserves they can buy assets from the RBA and obtain a better return then the cash rate less 25 basis points.

So money multpier does not apply and the research shows that because no one has been able to pin point what the number is because it keeps changing. It is a statisical measure that has no relevance.

JKH and Steven

I am not defending money multiplier theory. An unregulated bank does not need reserves or cash to promise you can spend that promise and transfer that promise to another of their customers. The issue i am wanting to deal with is the reality that banks need creditors to create money you can spend. If there is no creditor then the credit is set to zero and cash or reserves provided to the other bank or customer. And of course banks get flows from other banks all of the time because these banks zero their created credit and send what amounts to real money over.

Steven

>>actual cash is immaterial in our monetary system.

Cash and its electronic equivalent is the king pin of the Australian banking system. Each bank is like a man with a set of accounts in a temple. Each man deals with the other man via loans of ‘cash’ or actual ‘cash’. Yes it is true that each man can go to God for an interest only loan for the day if he offers an acceptable asset, and yes God will give an overnight loan in the same manner at his descretion – as published in advance. And yes God will offer longer term loans in the same manner if required if he is so inclined. But these longer term ‘standing facility’ loans only happen about 17 times a year according to the RBA. So each bank can swap a monetary asset for another monetary asset which is RBA money. And yet the rules of asset quality have been pushed to limits. But ‘cash’ is the glue that holds the system together even so.

Andrew,

One of the flaws to your argument is that you assume reserves are used to finance a loan. Have you ever left a bank after getting a loan with cash? Never! A bank is going to manage its cash position completely (or nearly so) seperately from its lending position. I work for a bank and we employ people to MINIMIZE the amount of cash held at the institution. We uses excess cash to buy bonds, float on the federal funds market all sorts of stuff to maximize its return. What we don’t do is call the lending group and tell them to make more loan. If by change the lending group does make more loans someone else in the finance group will make the proper balance sheet moves to ensure we met our regs, but that has little to no barring on how much cash we keep on hand.

JKH

While it is true no reserves at all are absolutely required to expand lending the creation of deposits leaves each individual bank exposed to a run, either from its own depositors or via another bank refusing to be its creditor.

Banks therefore have their own monetary policy. They have branch cash for example and more or less dare not totally run out of cash. Yes if you want more than 2000 and dont start screaming, you will be asked to come back tomorrow but even so we expect the cash machines to have cash in them somewhere in town.

So on the one hand there is the idea and indeed truth, that reserves are not needed and no fractional reserve is present and then the practical reality that this does not apply in the real world 99.99% of the time.

And more or less nobody can walk into a bank and get a loan of one million dollars and get that sent over to another bank on the spot. In reality lines of credit are available and interbank loans can be arranged by the time the customer gets the official word the funds are ready to be drawn down. A branch with no cash for example can reason that by 3pm it will have a few thousand it can lend to a customer and get securicor to deliver more as required. To say reserves do not need to be considered when a loan is made is just too simplistic.

“the creation of deposits leaves each individual bank exposed to a run, either from its own depositors or via another bank refusing to be its creditor.”

Not if the system is set up correctly with the central bank as lender of last resort. A bank run cannot happen if that is available if the central bank is part of the entity that issues the currency.

The bank might run out of physical notes, but can electronically transfer every deposit it has elsewhere. The central bank then clears it at the end of the day.

Any restrictions in place at the moment are down to system inefficiencies that are likely hangovers from the convertible era. Ultimately the central bank should just create the money and lend it to the bank as required. Since the central bank is the regulator of that bank, there can be no issue of whether the bank is good for the loan – unless somebody has been asleep at the regulatory wheel.

Adam,

>>One of the flaws to your argument is that you assume reserves are used to finance a loan.

Reserves or cash or an interbank loan are required to finance a loan if a loan needs financing. But of course many loans do not need financing for a considerable period of time, during which time other amounts of reserves and cash are continually streaming to the bank.

Yes dead cash does not earn a profit. The whole idea is to make a profit and maximise the amount of central bank money available.

If you have pre registered bonds held in Austraclear which your people are busy buying with surplus cash, you can get an instant RBA interest free loan of Reserves when you require them electronically without asking the RBA by selling that bond to the RBA electronically. You can then RITS over one million to another bank and because you have these bonds the transaction does not fail. You are however poorer by one million and have to buy that bond back by close of buisiness or arrange an overnight loan on the telephone to the RBA.

Neil

” the central bank should just create the money and lend it to the bank as required. Since the central bank is the regulator of that bank, there can be no issue of whether the bank is good for the loan – unless somebody has been asleep at the regulatory wheel.”

Regulation?? Do you really thing some human being working for the regulators is going to go visit each property and talk to each personal loan holder? You cannot believe that.

Which is why central banks only normally lend to their banks by taking collateral acceptable to the CB so that if the bank turns out to be a big turd they have some measure of security.

But you must realise regulation has been disasterously lacking??

‘Each day a bank has to know what its reserve position is likely to be so it can get cash if it needs it to maintain the branch floats. You simply cannot say that lending can happen independent of the reserve position. Banks already operate on the smell of an oily rag. They can’t regularly totally run out of cash or confidence would evaporate. If a large bank usually only lends a few hundred million max without arranging finance in advance (new deposits for the larger loans) then the branch float alone enables money multiplier to be correct for those lending instances.’

That’s why god gave us overnight banking loans and an international confederacy of national government fools: to ensure that monetary flows look like bank stocks that are in constant danger of totally running out of cash and the ‘oily rag’ of bankers is the only possible ‘smelling salts’ that can save the real productive capacity of the economy from an attack of vapours -as if.

Apologies, Andrew Wilkins, my immediate response to your words is less than tempered, analytical or reasoned, but my response is not intended to be disrespectful and is not a response to you or your opinion.

It is merely my own wee rant I needed to have to get my head around the above proposition.

I simply have spent too much of day picking up the pieces of people fragmented by the economic delusions of the ” Powers That Be” and their failed economic policies to put the concerns of banks first here.

There’s a lot on this site to disabuse anyone of the notion that banks are ‘doing it hard.’ Unlike most human beings, they don’t actually need cash to survive in the current configuration of the economy.

Specifically the above brings this post from Bill to mind.

‘So the level of bank reserves is a stock – measured at some point each day. Government spending and taxation, consumer spending, saving, investment, exports, imports, etc are all flows of dollars per unit of time. Government spending adds to bank reserves and taxation reduces (drains) the stock of reserve’ -Stock-flow consistent macro model – https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=4870

“Which is why central banks only normally lend to their banks by taking collateral acceptable to the CB so that if the bank turns out to be a big turd they have some measure of security.”

And that is the problem. The Central bank’s security is that the bank is properly regulated by them. In other words the capital buffer the bank has and the amount of loans against it is considered satisfactory by the central bank’s regulation team for the issue of a licence to operate a fractional reserve system on deposits.

Then if the bank does go titsup it is right that the Central bank funds the shortage of reserves caused by the fractional system, but only once the bank has been put into administration. That way shareholders and bondholders in the bank take a bath and depositors are protected.

That to me is how a bank with fractional reserve capability should be run under a fiat system once MMT shows you how it really works.

“But you must realise regulation has been disasterously lacking??”

It has, and because the government has fallen down on the job then they should have to foot the bill for their incompetence. The main failure is that bank shareholders have in a lot of case been left with some equity. They should have lost the lot.

FDIC has currently done just that to about 900 banks with a similar number on the watch list. Another 6 or so are judged too big to fail but I imagine some of those will get split up once this is all done and dusted.

FDIC only covers depositors up to 200,000. People who invest in bad banks also have to take a bath. Why should the tax payer protect them? Should the tax payer protect the depositing banks also? or just the frail and vulnerable depositors?

Andrew:

Reserves or cash or an interbank loan are required to finance a loan if a loan needs financing. But of course many loans do not need financing for a considerable period of time, during which time other amounts of reserves and cash are continually streaming to the bank.

And more or less nobody can walk into a bank and get a loan of one million dollars and get that sent over to another bank on the spot. In reality lines of credit are available and interbank loans can be arranged by the time the customer gets the official word the funds are ready to be drawn down. A branch with no cash for example can reason that by 3pm it will have a few thousand it can lend to a customer and get securicor to deliver more as required. To say reserves do not need to be considered when a loan is made is just too simplistic.

You are of, course right, about the reality of needing funding with base money for various cash outflows during bank daily operations.

In theory, banks can operate with zero base money borrowing from each other, as needed, on the interbank market at close to zero interest rate whatever their loan commitments might be. In other words, theoreticians assume “frictionless” interbank market. In practice, the bank that assume frictionless interbank network goes down the tubes with a pretty good degree of certainty.

One can imagine the banking network as a system of outflow channels (loans, lines of credit, withdrawals, etc.) and inflow channels (depositary base primarily). Those banks that neglect depositary inflows and rely to an excessive degree on interbank, wholesale deposits, etc., pay dearly or shift the cost of such reliance onto the taxpayer.

Even Basel III recognizes the reality of cash flow management (two previous Basels pretended that the interbank market was frictionless) and requires a 30 day cash/close to cash funds cushion with an assumption that the interbank, or any other source of cash, is unavailable during those 30 days in a “liquidity shock” scenario.

There is no uniformity with respect to cash flow(“liquidity”) management in the US. Practices vary widely from bank to bank, from spreadheet based estimation to almost real time monitoring of cash movement. Some do “fund transfer pricing” to include the cost of procuring cash into lending profit margins, some assume zero cost, but the majority clearly understand that the interbank market is not frictionless and the loan creation “ex nihilo” is just a crude approximation of what happens in real life.

”

In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.

“

Andrew:

I missed a comma in the following:

In theory, banks can operate with zero base money, borrowing from each other, as needed, on the interbank market at close to zero interest rate whatever their loan commitments might be.

VJK

Thanks. So is MMT described by “normal bank lending where you would create credit when you dont have any excess reserves and you worry about it later” or there more to it than that?

Andrew:

I am not the person to ask as I disagree with certain MMT ideas while recognizing validity of others. So, I would not dare to answer for fear of being accused of misrepresentation 😉

A true MMT’er, such as Scott Fulwiler or Mosler, would be a more reliable source of what MMT is about.

Bill,

On Estonia, here’s something that you’ll find to be of interest. Estonia seems to have conjured up the magic of cutting expenditures and increase taxes without the deficit going up. Estonia was different from Argentina — there the

cuts caused the deficit to increase.

You know how they did it? In 2007 the European funding to Estonia was 3,75 billion kroons. Then, it grew to 5.45 billion in 2008 and to 11 billion in 2009. The entire Estonian 2009 budget was 89 billion. Estonia’s dirty little secret — how to cut the budget and have income fall without the deficit going up. This is EU regional funding. In effect a massive fiscal transfer from those “profligate Europeans”!

In Canada, the banking system operates with 0 reserve balances held overnight.

It is a central tenet of MMT that banks require reserve balances to settle payments, and that the creation of a loan quite often (even usually) requires that a payment be settled. But, the issue is not whether or not an individual bank can acquire reserve balances–it can–the issue is at what price it can acquire them, and then how this price affects the profitability of the loan in question. When MMT’ers say banks are not constrained by reserve balances in making loans, they are pointing out that it is the price of obtaining reserve balances, not the quantity of reserve balances the bank has, that matters for deciding whether or not to make a loan.

Scott

Most systems today are operating with zero required reserves overnight. But if the total system reserves is a few hundred million and each bank holds bonds whereby each bank can get reserves during the day from the central bank it does not mean much. ‘Cash’ still holds the system together, and all banks are going to have cash in their branches where reserves and cash amount to the same thing – central bank money. If you have bonds you can electronically and programatically convert to reserves while wiring money to another bank the concept of no reserves is a bit meaningless. If the banks had no liquid monetary assets that would be a very different thing.

What i dont get here is that central bankers recognise the banks can lever up their balance sheets only subject to their ability to manage the liabilities that creates for them and that money multiplier theory is invalid. So this appears to make them MMT’ers. And yet other people on other forums saying they believe in MMT evidently do not understand how a bank operates. This blog does however understand how a bank operates with only the comments about cash being irrelevant. suggesting otherwise.

“People who invest in bad banks also have to take a bath. Why should the tax payer protect them”

Because the bank is licensed and regulated by the government to operate a fractional reserve system in its currency. If the bank fails, that’s because the regulators didn’t ensure the capital buffer was big enough for the loans the bank was undertaking.

Why should depositors who trusted a government licensed bank instead of putting their cash under the mattress lose out?

Andrew @3:31

Banks aren’t using these liquid assets to manage intraday liquidity. Prior to fall 2008, the Fed was making intraday loans to the banking system–without collateral–of about $40B each minute, and the average day’s peak intraday lending to banks was $150B. In Canada, the banks end up with net positive or net negative positions in reserve accounts from the day’s trading and then settle up with each other at the end of the day so that each has zero balance.

Andrew @23:26

When you say “finance a loan,” MMT’ers would say “settle a payment resulting from liabilities created by a loan.” No real disagreement, except the language is more precise. When the bank “books” a loan, it creates a deposit for the borrower that may or may not ever be withdrawn from the bank’s books (e.g., if the borrower makes a payment to another of the bank’s customers). No “finance” required–the bank doesn’t deduct its reserve account when it books the loan, only when the borrower withdraws balances from the bank.

Scott Fullwiler, “When MMT’ers say banks are not constrained by reserve balances in making loans, they are pointing out that it is the price of obtaining reserve balances, not the quantity of reserve balances the bank has, that matters for deciding whether or not to make a loan.”

Does the quantity of reserve balances influence the price that they can be obtained at though?

Scott:

In Canada, the banking system operates with 0 reserve balances held overnight.

Not quite.

The requirement of the settlement account is indeed zero as in some other countries.

In reality, let’s say during last October, the average settlement balance at BoC was about about $50M. Additionally, the banks held cash deposits with BoC in the amount of about $2.8B in May and about $151M recently, having apparently substituted < 3year bonds for cash lately if I am reading the BoC balance sheet correctly.

So, even the Canadian system does require some grease of base money to make it work, unsurprisingly.

In some sense, the Canadian system is freak of nature that, while being built on similar fragile, sandy foundations as any other banking system in the "developed" world, appears to be more robust.

Perhaps, it's a cultural thing that is only temporary. Let's hope not.

Stone

The CB sets the short-term rate, overall, by supplying whatever balances the banking system needs to keep the overnight rate at the target. Individual banks may find they pay a higher rate than this given credit risk/maturity/liquidity, etc. Much of it is done via negotiated lines of credit. Note that the only reason this occurs is that the Fed desires banks to do this off the Fed’s balance sheet. By contrast, MMT’ers like Mosler argue that the Fed should simply set the rates paid at short-term maturities for banks, and enable them to borrow from the Fed. The rationale is that the Tsy is on the hook for much of the bank’s liabilities, anyway, and the banks (in theory, at least) shouldn’t be holding any assets not approved by govt regulators–so, the view is that the prospect of forcing banks to private markets and the potential hits to their capital as a result is counterproductive (that is, given that the Tsy is on the hook).

Scott:

Prior to fall 2008, the Fed was making intraday loans to the banking system-without collateral-of about $40B each minute,

An intraday loan does not come for free: it costs 0.5% currently and is capped depending on the borrower capital.

The Feds most certainly require a collateral of good quality for discount window borrowing overnight.

The volume is interesting, though. Could you give a reference ?

Off topic I’m afraid but I thought someone might be able to give me a sensible answer quite quickly.

In the UK the Office for Budget Responsibility predict household debt to rise by £400 billion over the next 5 years.

Over the same period I understand accumulated budget deficits will be of a similar order.

If you add in the trade deficits doesn’t that mean we are looking at up to £1 trillion of savings or increase in private wealth somewhere else?

What am I missing ?

Thanks Scott, is the “logic” of the present system that although the government is on the hook, it is supposidly protected by the fact that bank shareholders will have a sense of self preservation that will curb reckless lending? If banks could borrow at commercially attractive rates from the central bank then wouldn’t that allow credit fueled asset bubbles to flare up to an even worse extent than at present? It sounds like the government would become charged with making the decision as to whether an expansion was a bubble (and so to be curbed) or a wise prediction of future value (and so to be encouraged). I’m afraid I’m yet to be convinced that the best way to make such decisions isn’t to have a system where providing credit to the fantastic new investment requires disinvestment from existing assets (ie a non-expanding monetary system) :).

Hi VJK

Banks (many of them, at least) can waive the vast majority of intraday borrowing expenses (at one point, it was the first $25 or something like that, but this covered most expenses for most banks–not large banks, obviously), but yes, there is a (very small–last I heard, it was about 1/2 what you are quoting at an annualized rate) cost to encourage them to minimize (again, Fed prefers to keep this off its balance sheet, and Congress has actually directed it to do that by charging for its services). One way banks avoid this is to try and batch/send payments during high payment flow periods of the day, since balances debited but then credited by incoming flow within the same minute do not incur daylight overdraft charges.

As for sources, there’s James McAndrews research at the NY Fed, and the BIS has a committe on payments systems that publishes annual data.

Stone . . . I suppose that’s part of the logic, certainly, but note that even with that, regulation of what’s on the asset side is always necessary. And note that high short-term interest rates don’t necessarily discourage speculative activity–the 1980s in the US are a case in point.

VJK,

The data I quoted in a paper I wrote in 2008 was from BIS 2005, and at that time the intraday overdrafts were $36B/minute, with an average peak of $116B. The data tended to trend up over time–don’t know if the $150B figure is exact or not, but it was floating in my head (so it must be right :)).

Scott

In Australia the payment system is set up to enable automatic intraday repo at no interest without any human contact with the RBA. Perhaps it is not used so often but the option is there. All that is required is that the necessary highest quality security is registered with the system so that ownership can be automatically transferred to the RBA. For other terms the RBA will not lend without elligible collateral for overnight or for longer term.

But it appears so far that i am an MMTer?

Scott

“When MMT’ers say banks are not constrained by reserve balances in making loans, they are pointing out that it is the price of obtaining reserve balances, not the quantity of reserve balances the bank has, that matters for deciding whether or not to make a loan.”

I would re-state slightly. Banks are not constrained by a shortage of reserves as long as (1) their capital position is adequate and (2) they have enough govt/semi-govt assets to repo in exchange for reserve balances.

Some some MMT-leaning posters (not yourself) seem to want to extrapolate this quite nuanced understanding to a very simplified position like “reserves don’t matter” or “reserves are irrelevant to bank lending” etc. This then becomes the standard response to any discussion over whether an EXCESS of reserves (not shortage as mentioned above) is inflationary or will stimulate additional lending.

Personally I think the situation of the large excess of reserves in the US does have the potential to be highly inflationary because the process of getting those reserves has involved banks selling mortgages and agencies for them, which improves their capital position and liquidity position in one go.

Stone,

The present price of a firm is a function of the expected future prices, which are a function of the current and future firm behavior, which itself is a function of the present price of the firm. So what would a non-expanding system look like?

How would you enforce it? The best you can hope for is some institutional limits and some form of reaction function, and then still you will occasionally have expansion, even if you only have securities to trade.

The creation of a contingent contract does not require any disinvestment, but these contracts have a price, and therefore can be sold to fund real investment. The matching “disinvest” consists of someone else holding a short position, but that position need not be closed until far in the future, so the disinvestment is separated in time from the investment, which is really the point of creating these contracts in the first place. If the disinvestment need not occur at the same time as the investment, then you can have expansion.

Here’s a nice survey of Arrow Debreu literature (e.g. attempts to argue that there exist equilibria with “rational” and “optimal” securities prices, with some gems:

Scott:

I found what is perhaps more recent info:

Overall, aggregate average daylight overdrafts averaged $62 billion per day in 2008, with aggregate peak daylight overdrafts averaging $169 billion each day. In 2008, ten institutions accounted for about 78 percent of total average overdrafts.

So, the growth is not so dramatic but close to what you’ve indicated. “ten institutions” is quite interestiong. One wonders what institutions ?

Ah, the reference:

//www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/files/fedfunds_coreprinciples.pdf

Scott Fullwiler,

Hi… Since you were on the topic of the costs of bank loans, perhaps you might be willing to consider some recent thoughts of mine and tell me if they seem mistaken. A couple related questions first.

You said “it is the price of obtaining reserve balances, not the quantity of reserve balances the bank has, that matters for deciding whether or not to make a loan.” But how big a factor is this in the loan-or-no-loan decision, really? In the US the reserve ratio is 10%, so a new $10,000 loan requires only an additional $1,000 in reserves. Even if the overnight rate was way up near 5% as it has been before, that would still only add 0.5% in costs to a potential loan, right? That’s not nothing, but you seem to imply cost of reserves as a dominant factor. I would have thought credit risk, inflation risk, interest rate risk, and the current interest rate on bank deposits would collectively dominate the loan rate determination. In fact, there should even be times when a bank makes money on its own reserves (when it has excess reserves to lend to other banks), rather than reserves always being a cost. (Yes I do realize the cost in that case could be the associated deposit liabilities, but I listed those above among other rate determination factors).

How does a company choose whether to borrow via a bank loan or via issuing a bond? How does a bank decide whether to hold a consumer loan or sell it to investors in some form (e.g., via Fannie/Freddie)? From a macroeconomic perspective, what competitive process determines the outcome of which type of lender ultimately funds a given prospective borrower?

I wrote up some tentative ideas on this because I didn’t find obvious answers in my searches, but I likely missed something… In summary it seems to me:

(1) the private sector should roughly self-determine its money supply semi-independently from the total borrowing it does, as an outcome of its bank lending vs non-bank lending decisions, and

(2) bank loans seem like a private sector “lender of last resort” rate anchor that should prevent longer term borrowing rates from rising above a fundamental level even when there is insufficient demand from investors/savers to trade bank deposits for longer duration assets.

It is not my goal to pollute the internet with fallacies so I’d love to amend my write-up if it’s way off or has been covered more accurately elsewhere.

Andrew:

All that is required is that the necessary highest quality security is registered with the system so that ownership can be automatically transferred to the RBA. For other terms the RBA will not lend without elligible collateral for overnight or for longer term.

Fedwire operates in a similar way: free when collateralized intraday or 50 bps charge plus cap uncollateralized; must be collateralized overnight. Not sure about the automatic part.

VJK . . .yes, very interesting stuff. Thanks for posting.

Andrew . .. so far, so good! 🙂

Gamma . . . agree that in so far as MBS purchases by Fed improved capital, it helped lending “capacity,” Excess reserves have nothing to do with it, though. Consider, for instance, if the Fed would have simultaneously issued time deposits to drain the reserves created by the MBS purchases–lending capacity is unchanged (aside from the difference in interest earned on Fed time deposits and reserves, which would affect profits and capital) while excess reserves are largely eliminated.

I do have a problem with the presentation so far about banks being able to get reserves, when they want them, at very short notice at some cost, where the central bank is providing reserves at the target rate.

Banks have to provide reserves by wire in real time for many transactions. So unless they have prearranged lines of credit they can instantaneously draw upon there is no way they can turn up and wing it on the fly by ‘going to the market’.

Both RTGS RITS run by the RBA and Fedwire enable a bank to access intraday loans from the feds but this is only possible for institutions with good quality assets as far as i know. Certainly directly so for the RBA and probably indirectly so for the Feds.

think about it, you have a hundred branches across the country and you are saying that nobody knows the state of play of the current loans in transit or the likely demand for reserves for the season, or the day of the week, or day of the month, and the loan officer can just say yes and agree the draw down day and whatever reserves are required on the moment can be supplied and they never fail?

What we know from the RBA is that only about 17 times in total do the combined banks have to go to their version of the discount window, where this facility is used by banks that have miscalculated their reserve requirements for that day and get caught out *and* they have to provide collateral.

The reality of the big banks is that they all have accounts with each other and have lines of credit ready to go. So one bank might not have any reserves but it can simply ask for its deposit back to supply them, or net an amount of a deposit present at the receiving bank and this all happens via agreement long before the loan officer gets up in the morning.

For the Fed, at least, Regulation J guarantees that a payment sent via Fedwire will settle, whether or not the bank has requisite balances in its account. As far as I know, the Fed doesn’t reject payments, only penalizes. I have never seen anything explicitly noting the Fed would reject a payment sent via Fedwire, though that doesn’t mean it won’t happen. I do recall the Fed proposing doing so a few years back, but then it decided not to.

“The reality of the big banks is that they all have accounts with each other and have lines of credit ready to go. So one bank might not have any reserves but it can simply ask for its deposit back to supply them, or net an amount of a deposit present at the receiving bank and this all happens via agreement long before the loan officer gets up in the morning.”

I fail to see how this contradicts MMT or validates the money multiplier.

This discussion has so far completely ignored the pivotal role of commercial bank money market operational functions – the purpose of which is to attempt as best as possible to square reserve accounts on an overnight basis through offsetting transactions with non-bank counterparties (e.g. wholesale deposits from regular institutional clients, or treasury bill purchases), by taking into account as best as possible the reserve effect of non-money market transactions such as loan draw downs – and quite apart from the in and out intra-day operations of any central bank overdraft facility for the payment system.

“think about it, you have a hundred branches across the country and you are saying that nobody knows the state of play of the current loans in transit or the likely demand for reserves for the season, or the day of the week, or day of the month, and the loan officer can just say yes and agree the draw down day and whatever reserves are required on the moment can be supplied and they never fail?”

You still haven’t understood the argument. The argument is that what matters for the bank is the PRICE of obtaining reserves to settle a payment. (And, of course, it’s not altogether clear there will be a debit to the reserve account when proceeds from a loan are drawn down–the borrower could make a payment to someone already banking at the lending bank, or the payment could go to one of many netting clearinghouses, or the payment could be sent at the same minute as an incoming payment as banks in the US try to do, etc., etc.). The CB essentially guarantees that sufficient reserve balances will be supplied to the banking SYSTEM at the price it sets–and if there is pressure on the rate to rise, more balances are supplied. Since most or even all CBs don’t want to take all interbank lending onto their balance sheets, this means that there is some pricing based on credit risk, etc., for individual banks, as these balances are distributed to where they are wanted. BEFORE IT MAKES THE LOAN, the bank has considered (a) whether it might have a liquidity need if it makes the loan, (b) what this might be, and (c) what the price of obtaining this liquidity will be, and (d) how obtaining this liquidity will affect the profitability of the loan. THIS IS WHAT MMT SAYS WILL HAPPEN, and IT IS NOT CONSISTENT WITH THE MULTIPLIER THEORY which argues that the constraint is quantity. For all the attempts you have made at critiquing MMT, YOU HAVE NOT YET ADDRESSED THESE POINTS that form the core of the MMT argument. In fact, the points you’ve made are already contained within the MMT understanding.

JKH @8:59

I didn’t think we’d gotten that far yet, actually. But, yes, that’s another layer to add, obviously.

Also, JKH, that’s at least implicitly included when MMT’ers say “it’s about price, not quantity,” when explaining why the quantity of reserve balances does not constrain bank lending.

VJK @ 4:37

The operations of the Canadian banking system and the Bank of Canada (BoC) have the advantage of being very clear and not confused by the unnecessary requirement of banks holding excess reserves. The BoC releases all the relevant info on its website. With respect to excess settlement balances (excess reserves in the US), the BoC required 0 until the financial crisis hit, then required $3 billion to ensure the interest rate stayed at the floor rate which the Bank set at 0.25%, then in June 2010 it phased in 0 settlement balances again (in fact $25 million of ”grease” as you call it) over a few weeks. That explains the $2.88 billion and lower numbers later I believe. Currently excess settlement balances are $25 million, the approximate 0 the Bank uses.

The Canadian banking system is not a freak of nature but rather a tightly regulated, quite conservative, oligopoly. There are only half a dozen large very profitable banks that don’t take large risks because it is not in their interest to do so. In a nutshell that is why they sailed through the financial crisis without requiring any capital injections. Some support was provided them when the BoC engineered an asset swap of mortgages for Government of Canada securities. The mortgages were already largely guaranteed by another Government of Canada entity.

JKH:

wholesale deposits

They were mentioned earlier in the discussion.

It is very well known that wholesale deposits are *less* reliable and *more* expensive source of funding than retail deposits.

VJK @9:12 . . . very true, but nevertheless big banks (which do the bulk of the lending among banks) use wholesale sources to manage their payment settlement at the margin, as JKH noted.

Exactly, Scott.

FALLACY OF COMPOSITION, FALLACY OF COMPOSITION, FALLACY OF COMPOSITION, FALLACY …

This subject of bank reserves, along with everything else in economics, depends on understanding it.

And that’s really all there is to understanding economics.

Keith:

Not contradicting in general, but just clarifying:

settlement balances are $25 million

You took the lowest number during Oct. The average is about $50M.

It is not the settlement account balance that fell from $2.88B to $25/50M, but the additional cash deposits with the BoC that fell to $150M.

That means the *total* deposits with the BoC are about $200M, currently, rather than $25M.

I may be misreading the balance sheet, but that’s unlikely.

large very profitable banks that don’t take large risks because it is not in their interest to do so.

The Canadian banking system is no different, in essence, from the American or Australian one. It is as broken by design as the other two.

According to available information, some “large very profitable banks” were quite willing to engage in the same kind of suicidal activity as their American counterparts, but the regulators prevented them from doing so.

So, their robustness is explained by cultural factors (conservatism, tradition, etc) rather than some technical reliability features. That’s exactly what I meant by “a freak of nature” epithet which should be considered a praise rather than condemnation.

Andrew,

The source of our disagreement over at TalkFinance was your statement:

>And how does a private bank do something that i cannot do?<

You clearly understand banking systems much better than I do, but you still haven't convinced me that banks do nothing you cannot do.

Our discussion has covered much ground as I try to figure out the basis for your statement. I've learned quite a bit in doing so, and that is good. It has made me be more precise with the words I use as it's very easy to go round and round on a misunderstanding of terms.

I’d just like to diferentiate myself from the other Andrew. As regular readers will know, my banking knowledge is hazy, so I stay clear of bank operation discussions. Doesn’t look like any macro-economic points were made. Aside from that, I’d be really ashamed if I was caught defending the banking system.

In response to the references to accounts in a temple and visits to the RBA God…. The only time Jesus ever got violent was with the money lenders at the temple. Annoyed with their marked up exchange rates and extortionate fees.

After 2000 odd years nothing much changes does it.

Scott

>>You still haven’t understood the argument.

That is your opinion. In Australia if you dont have the reserves for RTGS your request will be requeued and you have one minute to get them before it fails. You can repo with the RBA automatically. The RBA claim they are not at risk during settlement. They claim you have reserves for settlement or it fails.

If other central banks are at risk during settlement the situation is obviously different as the private bank does not have to think much about the situation now and can work out something during the day – as JHT is talking about with overnight lending etc which supposedly ‘we have not got to yet’.

I am not defending the banks or Money multiplier theory! I am just trying to work out what MMT is. As you can see from Jeff65, he thinks the banks have some kind of special power that is not available to any individual able to retain savers who offers credit. Even a small credit provider could go to his lender of last resort if push came to shove and he can afford the loan. Another MMTer i spoke to had the same problem understanding what i was saying – hence i came here.

I realise lines of credit do not support money multiplier theory. However it is still true that when the loan officer gets up in the morning his lending is covered by the prior willingness of other banks to support his credit if the liabilities created cannot be managed by only the banks new borrowing – which seems to be the thrust of what people are saying here.

Andrew & Co, why did you come here pickering from steve keen’s finance forum when we have perfectly good blog post from bill mitchell here, some of us would like to, maybe, um you know… discuss it and eurozone problems, instead of having to read your mindless rants about some esoteric off-topic issue? Please.

Dear Poop3r (at 2010/11/03 at 17:53)

Thanks for your comment but remember that we are polite to each other when making comments.

And why not discuss the blog in question and let us know what you think of the Eurozone problems? Any constructive input is more than welcome.

best wishes

bill

Also i am really struggling with the way you talk about reserves as being everything but dont take account of the way cash moves out of the jointly owned private cash warehouses or central bank cash warehouses upon payment of reserves and vice versa, where the banks have a substantial cash float in all of their branches and the ATM’s and need to maintain it all day long, where it cannot be instantly replaced by overdrafts with a central bank permitting overdrafts.