The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

In austerity land, thinking about fiscal rules

I am now in Maastricht, The Netherlands where I have a regular position as visiting professor. It is like a second home to me. The University hosts CofFEE-Europe, which we started some years ago as a sibling of my research centre back in Newcastle. My relationship with the University here is due to my long friendship and professional collaboration with Prof dr. Joan Muysken who works here and is a co-author of my recent book – Full Employment abandoned. Our discussions last night were all about the Eurozone and I was happy to know that most of the Dutch banks are now effectively nationalised as part of the early bailout attempts. It is also clear that the ECB is now stuck between the devil and the deep blue sea. If it stops buying national government debt on the secondary markets those governments are likely to default and the big French and German banks the ECB is largely protecting will be in crisis. Alternatively, every day it continues with this policy the more obvious it is that the Eurozone system is totally bereft of any logic. Once the citizens in the nations that are being forced to endure harsh austerity programs realise all this there will be mayhem. The other discussion topic was the possible revision of the fiscal rules that define the Maastricht treaty. That is what this blog is about.

On the plane coming over here – in between reading Swedish detective novels and designing my macroeconomic simulation model that I am presenting here I watched the movie The Most Dangerous Man in America which is the story of Daniel Ellsberg and the way he leaked The Pentagon Papers to the press in the early 1970s. The leak exposed that four US presidents (Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson) had systematically lied to the American people which ultimately had the effect of putting their troops in fatal jeopardy. 58,000 US soldiers died in the Vietnam sham which was a lie from the start. I note that 2 million Vietnamese also died.

The point is that the lies also extend to the way the top office runs the largest economy in the world and to the top office in most countries.

Anyway, there has been a lot of discussion among the commentators of this blog about the constraints that different sectors face in the course of their decision making. While I welcome comments and diversity of perspective and certainly I welcome technical corrections in conceptual matters I have found some of the discussion to be somewhat at odds with my desire to achieve a perspicacious understanding of how the different sectors (government and non-government) work in a modern monetary system.

The clear intent of some of the inputs has been to suggest that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) which I have helped to develop as a principle part of my academic work is somehow “simplistic” and misleads people into believing that the government sector faces different constraints to the non-government sector. One comment concluded that the government sector in a fiat-currency issuing nation is financially constrained just like a household. To which I say – BS – which is the polite way of saying rot!

Understanding what a sovereign government is

We often need reminding of just what a sovereign nation is. The distinction between sovereignty and non-sovereignty is crucial to understanding how the monetary system operates and the options that the government has under the two states. For example, the financial press call Greece a sovereign nation when it clearly doesn’t issue its own currency, has to take the interest rate set by the ECB, and uses a currency that is not floating (for it) in the foreign exchange markets (that is, bears no direct relationship to its net exports and net capital flows). That is not a sovereign nation.

Essential background reading includes the following blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Then you should read these more specific blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3.

A national government in a fiat monetary system has specific capacities relating to the conduct of the sovereign currency. It is the only body that can issue this currency. It is a monopoly issuer, which means that the government can never be revenue-constrained in a technical sense (voluntary constraints ignored). This means exactly this – it can spend whenever it wants to and has no imperative to seeks funds to facilitate the spending.

This is in sharp contradistinction with a household (generalising to any non-government entity) which uses the currency of issue. Households have to fund every dollar they spend either by earning income, running down saving, and/or borrowing. Clearly, a household cannot spend more than its revenue indefinitely because it would imply total asset liquidation then continuously increasing debt. A household cannot sustain permanently increasing debt. So the budget choices facing a household are limited and prevent permanent deficits.

These household dynamics and constraints can never apply intrinsically to a sovereign government in a fiat monetary system.

A sovereign government does not need to save to spend – in fact, the concept of the currency issuer saving in the currency that it issues is nonsensical. A sovereign government does not need to borrow to spend. A sovereign government can sustain deficits indefinitely without destabilising itself or the economy and without establishing conditions which will ultimately undermine the aspiration to achieve public purpose.

Further, the sovereign government is the sole source of net financial assets (created by deficit spending) for the non-government sector. All transactions between agents in the non-government sector net to zero. For every asset created in the non-government sector there is a corresponding liability created $-for-$. No net wealth can be created. It is only through transactions between the government and the non-government sector create (destroy) net financial assets in the non-government sector.

This is an accounting reality that means that if the non-government sector wants to net save in the currency of issue then the government has to be in deficit $-for-$. The accumulated wealth in the currency of issue is also the accounting record of the accumulated deficits $-for-$.

So when the government runs a surplus, the non-government sector has to be in deficit. There are distributional possibilities between the foreign and domestic components of the non-government sector but overall that sector’s outcome is the mirror image of the government balance.

To say that the government sector should be in surplus is to also aspire for the non-government sector to be in deficit. In a nation such as Australia, where the foreign sector is typically in deficit (foreigners supplying their savings to us), the accounting relations mean that a government surplus will always be reflected in a private domestic deficit. This cannot be a viable growth strategy because the private sector (which faces a financing constraint) cannot be in deficits on an on-going basis. Ultimately, the fiscal drag will force the economy into recession (as private sector agents restructure their balance sheets by saving again) and the budget will move via automatic stabilisers into deficit.

The relationships between a sovereign government and the non-government sector cannot be defied. Private debt build up can allow the government to run surpluses for some time (when the balance of payments is in deficit) but not for very long.

Sub-national governments who use the currency of issue are akin to a household in that they face financing constraints. The only (and major) differences between a household and a sub-national government is that the latter typically has the power to tax (or levy fines) and can thus access cheaper funds in the debt markets as a consequence. While a sub-national government does have some risk of insolvency the reality is that it is extremely low and close to zero.

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability involves a conceptualisation of a government which is free of financial constraints and has a range of possibilities that are not available to any non-government entity. It would never invoke a notion of public solvency. A sovereign government is always solvent (unless it chooses for political reasons not to be!)

Further, given the non-government sector will typically net save in the currency of issue, a sovereign government has to run deficits more or less on a continuous basis. The size of those deficits will relate back to the pursuit of public purpose.

I also note that some people do not like the term “fiat”. It is what it is – a legislative statement (the “fiat”) that the currency of issue is required to extinguish non-government tax liabilities and is issued under the legislative power vested (as a monopoly) in the national government. It is a totally appropriate term for what it describes. The currency has no intrinsic value. Its value is given by the fiat held and dispensed by government.

With that discussion in mind, the following constraints can be usefully identified.

A sovereign government is never intrinsically financially constrained. If you think otherwise then I am sorry to say that you do not understand the nature of the monetary system. Yes, the government may impose a voluntary constraint on itself – for example:

- It might say that it has to borrow a matching sum from the private bond markets and put it in some bank account at the central bank before it can spend that sum.

- It might say it has to have a matching sum of tax revenue in some bank account at the central bank before it can spend that sum.

- It might say the Treasurer has to run three times around the block and count up to a number in 2s before it can spend the sum of the Treasurer’s recitation.

All that and more might form part of the day-to-day institutional machinery that regulates the transactional relationship between the government and non-government sectors. But none of these “constraints” are financial in nature and they stand in denial of the essential or intrinsic characteristics of the fiat monetary system.

These constraints are ideological and/or political in nature and have no intrinsic standing when the underlying (true) fiscal capacities of the government are considered. A sovereign government can never be revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. It is only when it imposes these voluntary (unnecessary) constraints on itself that it might appear to be revenue-constrained. But those constraints are only to be understood within the flawed logic that led to the ideologically-based restrictions. They have no standing outside of that and certainly no standing in relation to the underlying characteristics of the monetary system.

The only economic constraint that a sovereign government then faces is what we term the real constraint. Nominal public spending may be unlimited in capacity but given that the object of such spending is to garner public control of real goods and services then clearly the availability of these goods and services for sale becomes a binding constraint at some level of economic activity.

The government desires to access these real goods and services so that it can advance its conception of public purpose which is derived from the socio-economic mandate it received upon its election. Clearly, if the government was to push nominal spending beyond the capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output then it would be in breach of this responsible charter – all it would be doing is promoting inflation once there was no capacity for the economy to grow further in real terms.

So the inflation barrier becomes the real constraint on government spending. This is obvious but then the question becomes what is that barrier? There is a huge disparity of views with the mainstream macroeconomics paradigm – dominated by the flawed concept of the NAIRU adopting much slacker levels of real resource utilisation than would be the case if an employment buffer stock capacity – such as the Job Guarantee.

If there is a buffer stock of jobs unconditionally available at a fixed wage then the national government can always afford to provide them and in doing so they create a nominal anchor that provides for stable inflation.

Some people claim that there is another constraint on a sovereign government that MMT ignores to its detriment – the external balance. The claim is that fiscal policy will promote a worsening external situation which will ultimately see the currency collapse and inflationary pressures and foreign debt escalation forcing the government to move towards surplus to stabilise the economy.

But how does this stop the national government from using fiscal policy to maintain the highest levels. The may be constraints on the overall economy arising from external sources. MMT always acknowledges that the only way a nation can enjoy the real terms of trade benefits associates with an external trade deficit (more real goods and services entering the nation from abroad and going the other way) is because, in a macroeconomic sense, the foreign sector desires to accumulate financial claims (bits of paper) denominated in the local currency.

It is clear that this desire can change and if it disappears then the flow of imports into the economy will contract as quickly as the desire to accumulate the financial claims contracts. It is surely a constraint on citizens living in the local economy. One day they are enjoying lots of imported gadgets and the next they are being forced to go without them (in a macro sense). That is an external constraint. The desires to accumulate financial claims in the local currency are the desires of foreigners – and can change. So what?

But that doesn’t impose any intrinsic constraint on the government capacity to use fiscal policy to advance public purpose. Except in extreme cases where all food is imported, the government can always employ any idle labour to the benefit of domestic production regardless of the external situation. A depreciating currency places no constraints, for example, on a sovereign government unconditionally offering a minimum wage job to anyone who wants it.

A depreciating currency also sets in play forces that reduce the underlying terms of trade effects on the nominal exchange rate anyway and serve to reinforce expansionary fiscal policy not threaten it. Some might say the threat of imported inflation renders fiscal policy hostage to the exchange rate.

First, the actual impact of price rises arising from depreciation is dependent on how significant imports are to the total consumer price index. Mostly, the impact is low. Clearly, when there is a major supply price shock the situation is different.

The inflation of the 1970s was not the same beast that the deficit terrorists are telling us is just around the corner now. In the mid 1970s there was a huge price rise in oil as the OPEC cartel flexed its muscles and knew that the oil-dependent economies had little choice, at least in the short-run, but to pay up. This represented a real cost shock to all the economies – that is, a new claim on real output. The reality is that some group or groups (workers, capital) had to take a real cut in living standards in the short-run to accommodate this new claim on real output.

At that time, neither labour or capital chose to concede and there were limited institutional mechanisms available to distribute the real losses fairly between all distributional claimants. The resulting wage-price spiral came directly out of the distributional conflict that occurred. Another way of saying this is that there were too many nominal claims (specified in monetary terms) on the existing real output. This is sometimes called the “battle of the mark-ups”; the “conflict theory of inflation” or the “incompatible claims” theory of inflation. Sometimes this is referred to as “cost push” inflation because its initial source is a push upwards in costs that are then transmitted via mark-ups into price level acceleration especially if workers resist the real wage cuts that capital tries to impose on them – to force the real costs of the resource price rise onto labour.

Ultimately, the government can choose to ratify the inflation by not reducing the nominal pressure or it can break into the wage-price spiral by raising taxes and/or cutting its own spending to force a product and labour market discipline onto the “margin setters”. The weaker demand forces firms to abandon their margin push and the weakening labour markets cause workers to re-assess their real wage resistance. That is ultimately what happened in the 1970s.

However, under a Job Guarantee policy, the labour market slack required to discipline the wage-price spiral would manifest as a redistribution of workers into a fixed price employment sector (the JG) rather than under a NAIRU approach (the current approach) that forces workers into a buffer stock of unemployed. MMT tells us that the welfare losses of the latter are much large than under the former.

MMT also tells us that the national government can always afford to buy the services of any idle labour that wants to work. But the important part of the inflation control mechanism in the JG is that the government should not buy this labour at “market prices” but rather pay a living minimum wage. At any time the private sector can re-purchase the labour services by paying a wage above this.

Anyway, now that I am travelling in the lands of austerity the issue of voluntary constraints is central in my mind. The British government has decided that it doesn’t like its sovereign status and wants to bolt itself down with some pre-conceived notions of fiscal prudence. We are already getting a sense that the impacts of this approach will be very destructive. We have seen Ireland leading the way in the how to damage the economy by relinquishing government sovereignty.

So this discussion led me to think about fiscal rules again. A lot of readers have written to me asking me to explain in more detail why I am totally opposed to the use of such rules. One response is simple: they generally don’t work if they are designed to impede government actions. When they do work in the way the designers intended they are destructive. But to understand these points I though a little simulation exercise with some narration might help.

Please read my blog – Fiscal rules going mad … – for more background discussion on fiscal rules.

So many readers write to me wanting me to specifically explain my abhorrence to what they think are reasonable fiscal rules – that is voluntary constraints imposed on the government’s budget inputs and/or outcomes in the interests of “discipline”. I actually always thought that in a democracy the ballot box was the disciplining device and in between elections we wanted governments to act in our best interests according to the mandate that they won at the time of the election.

It would appear to me to be the anathema of democracy to constrain our elected representatives to rules determined by faceless officials who are not accountable to us for their actions. In that context, I always find it curious that the freedom loving Americans who never cease to tell us non-Americans how strong their democracy is yet also seek to constrain their governments with mindless rules.

As an aside, the Daniel Ellsberg story I noted at the outset certainly should disabuse anyone of the notion that America represents a robust democracy!

In terms of fiscal rules, consider the Maastricht treaty which says that the budget deficit of any member nation has to be below 3 per cent of nominal GDP. Should the deficit exceed that then the government has to contract its discretionary fiscal stance in an attempt to bring the deficit down below that ratio. Apparently some one has constructed the 3 per cent as something meaningful. The imposition of that rule is in fact arbitrary – there is no hard analysis which suggests 3 per cent is “better” than 4 or 2 or 3.5 per cent.

To get some background on fiscal rules, you might like to read the paper – Fiscal rules OK>? – published in January 2009, by the Centre-Forum which is a UK-based “liberal think tank”.

At the outset they note that:

After 16 consecutive years of economic growth, the UK is now facing the sharpest downturn in a generation. The crisis is also wreaking havoc with the public finances. Government debt is set to spiral to levels not seen since the 1970s. This explosion in debt represents a failure for Labour’s economic policies, above all its promise to bring order to fiscal policy through the application of strict rules. But the Conservatives are wrong to think that their proposed ‘independent fiscal council’ would be any more successful …. there is no straightforward definition of what constitutes ‘good’ fiscal policy … Fiscal policy is a political issue. The question of how to tax, spend and borrow cannot be deduced by technical calculation. There is no simple answer to whether 40, 50 or 60 per cent of GDP is an unsustainable level of debt. Labour used the fiscal rules to divert voters’ attention from the political choice that was being made for them: of higher long term debts in return for investment in public services.

And in that statement and what follows you see the classic deficit-dove perspective emerging that is often characteristics of the progressive or “liberal” response to neo-liberalism. I do not find it a compelling response at all.

First, there is no intrinsic meaning to the term “wreaking havoc with public finances” when applied to a sovereign national government. There is meaning to an analysis that traces a rising budget deficit to the response of automatic stabilisers which signal that the real economy is slowing and unemployment is rising. That is a “bad” situation and the rising deficit is the canary. But equally, a rising budget deficit might indicate a demonstration of leadership by the government committed to smoothing the business cycle and using its discretionary spending and taxation capacities to maintain high levels of activity in the face of fluctuations in private spending. The is a “good deficit”.

So the havoc was being wrought in the real sector. An emphasis on what the canary was doing largely distracts us from the nature of the budget balance and biases the public debate towards having to “fix the deficit”. This is not a productive route to take because it immediately plays into the hands of the neo-liberals and confines the discussion to what the deficit should be – in isolation to what is happening elsewhere in the economy.

Further, discussing the possibility that a public debt ratio could be unsustainable is the hallmark of a deficit dove. What do they mean by unsustainable? That is, forget the calibration, what could it mean in concept? For a sovereign government no ratio would ever be unsustainable even though within the typical ranges that the business cycle historically swings very high debt ratios are highly unlikely.

Unsustainable means that the government faces a solvency risk. No sovereign government can ever be insolvent unless it borrows in foreign currencies. Please read that as never! So if unsustainability means something else then it would be good to have that clearly articulated.

Does it mean that the income payments involved in servicing a growing debt ratio will become excessive? Excessive in relation to what? Certainly not in nominal terms because a sovereign government is never revenue constrained. So perhaps the payments will push the growth of nominal aggregate demand beyond the real capacity of the economy to absorb it via real production increases. Any component of nominal spending growth – private, external or public – might be implicated in that risk. Why single out interest-servicing payments?

But if that was the case then the government has the capacity to eliminate that risk fairly quickly. For example it could reduce interest rates and/or increase taxes. Yes, you might ask – with independent central banks how would it achieve that? Well it could legislate to make the central bank part of treasury if it really wanted to. But the point is that this “unsustainability” – is nothing intrinsic to public debt. If the nominal aggregate demand hits an inflation barrier then functional finance tells us the government should do something about that.

You pick up the implicit biases in the Centre-Forum paper when you read that:

In contrast to monetary policy, there is no economic or political consensus about the goals of good fiscal policy.

The so-called consensus about monetary policy is a purely neo-liberal construction. The shift to constructing monetary policy as the primary vehicle to maintain inflation stability and in doing so, use unemployment as a policy tool rather than a policy target (the NAIRU unemployment-buffer stock approach) is only acceptable among mainstream economists. Monetary policy hasn’t always been seen in that way.

If you examine the legislative acts that set up central banks you will see that they were typically entrusted with maintaining full employment, price stability and external stability. It is only during the neo-liberal period that this focus has narrowed to maintaining price stability. The way they have avoided the obvious criticism that they have abandoned their charter to maintain full employment, given that they have used unemployment capriciously as a policy tool, is to redefine what full employment is.

This is the NAIRU ruse – the full employment level of unemployment just rises or falls to suit their rhetoric. In that way they can always say they are acting within their original charter despite the reality that they abandoned it years ago. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

MMT has a very clear construction of what full employment means – it requires there be sufficient jobs and working hours to match the preferences of the workers at the current wage levels.

The Centre-Forum paper then defines what it considers to “to describe the character of good fiscal management”. First, good fiscal management involves:

Achieving low borrowing costs – High and unpredictable borrowing undermines confidence in the financial markets, which punish the government by charging a greater interest charge for lending.

I do not care to describe “good fiscal management” in terms of ideologically-motivated practices such as debt-issuance and the arrangements surrounding that which give unnecessary power to the recipients of corporate welfare (the bond markets). Rather good fiscal management should allow the government to pursue its mandate without being threatened by the sectional interests (bond markets) which rarely coincide with the overall national interest.

Second, the Centre-Forum paper says good fiscal management involves:

Avoiding a ‘deficit bias’ – The benefits of short term fiscal profligacy usually accrue to the current government, leaving future administrations to repay the debt. This produces a bias in favour of deficits. It can also allow the concerns of the present to unfairly outweigh those of the future, undermining fairness between the generations.

This “characteristic” is based on the fallacious nation that the “debt-burden” associated with deficits is borne by the future generations (especially if the net spending associated with the debt is underpinning current consumption – such as transfer payments). This notion is a mainstay of mainstream macroeconomics and assumes that the government pays back its debt by raising taxes at some future period.

Of-course it is very rare that a government ever pays back its debt (in a macroeconomic sense).

Third, the Centre-Forum paper says good fiscal management involves:

Smoothing the economic cycle – Government tax and spending decisions can increase macroeconomic volatility by boosting demand during upswings and cutting back during downturns. Even when macroeconomic stability is delegated to an independent central bank, excessive government deficits can compromise this independence by forcing it to raise rates to head off an inflation threat.

Any government can misuse its fiscal capacity and engage in damaging pro-cyclical net spending changes. This is exactly what the austerity packages are doing at present – contracting the government’s contribution to overall spending at the same time as the economy is in recession. That is the height of irresponsible fiscal behaviour.

But one should not assume that running a deficit during a growth period or expanding net public spending (that is, increasing the deficit) is poor fiscal practice. It all depends on the state of non-government spending and the extent of idle resources in the economy. A pro-cyclical policy response when there is high unemployment and early stages of a private recovery is sound practice.

Governments should not, however, push aggregate demand beyond the capacity of the economy to absorb it in real terms. But why would a sensible government want to do that anyway?

Fourth, the Centre-Forum paper says good fiscal management involves:

Stimulating government investment – Public investment has benefits that accrue over many years. Governments in financial difficulty find it easier to cut potentially beneficial investment plans than current spending: responsible fiscal policy should avoid such short sighted behaviour.

I largely agree that public infrastructure development is a sound fiscal goal in the sense that it allows higher quality public services to enhance the lives of the citizenry and allows private activity to lever off the capacity created (for example, road, transport and port systems etc).

I also agree that governments who are alleged (by neo-liberal standards) to be in “financial difficulty”) cut capital works because the effect of these cuts are less obvious in the short-term. The point that should be borne in mind is that what a neo-liberal defines as “financial difficulty” is usually nothing of the sort. A sovereign government can never get into “financial difficulty” as long as it doesn’t borrow in a foreign currency.

So typically governments who claim they are in “financial difficulty” are in fact just asserting an ideological distaste for public deficits (which suggest larger government access to available real resources) and a desire to allow the market to operate in a less fettered manner. I don’t share that ideological distaste which doesn’t mean I am uncritical of government involvement in the economy. My position is simple. The fact is that government is a central player in a modern monetary system whether you like it or not. I would rather design processes where the democratic scrutiny of the citizens operating with much greater access to information about government decision-making “keeps the bastards honest”.

As an aside, the “keeps the bastards honest” epithet was the motivation for the formation of a political party in Australia in the 1970s – The Democrats – who showed over time they couldn’t be honest themselves and have now faded into electoral oblivion.

The Centre-Forum paper says that:

The purpose of fiscal rules is to bind a government into responsible behaviour that may not always be in its short term interests.

They discuss the concept of “time inconsistency” which was at the centre of the orthodox attacks on the use of discretionary fiscal policy. This idea suggests that what the government might hold out in one period as being desirable may be jettisoned in another period (as an election approaches). So apparently, running a budget surplus is deemed to be desirable because it allegedly keeps interest rates low and avoids imposing debt-burdens on future generations. But then during an election campaign the pork barrelling to attract votes may lead to governments abandoning that earlier commitment.

If you think about this for a moment you will realise how dependent an evaluation of whether the government is being capricious depends on the validity of the original promises and the identification of legitimate changed circumstances. A government running a tight fiscal position in the face of a major private sector spending boom may be responsible. But it doesn’t make it irresponsible a year later to run a very expansionary fiscal stance if private spending has collapsed.

This would only be considered “irresponsible” and “time inconsistent” if you held the position that any fiscal response to counter-stabilise the business cycle was undesirable. Which of-course is the position that the deficit terrorists seek to impose on governments to the detriment of the overall economy.

Given elections are regular – the ultimate judge of whether the government is behaving capriciously should be the informed voter. Imposing inflexible rules on government that prevent it reacting to legitimate changes in economic circumstances is a denial of the purpose of fiscal policy. Which of-course is the intent of those who seek to impose fiscal rules in the first place. They don’t want fiscal policy used in any discretionary sense.

So when the Centre-Forum paper says that:

Fiscal rules are designed to encourage governments to stick to their original tax and spending plans by increasing the political cost of breaking past commitments, or even making it a statutory requirement complete with penalties for non compliance.

You can immediately appreciate the ideological nature of the rules. The government would only incur a political cost in changing fiscal tack to suit the spending decisions of the non-government sector if the citizens were misled into believing that fiscal policy was not a valid policy instrument. If instead of focusing on the deficit the media focused on the change in unemployment (as an ultimate evil) then the public would make very different political judgements of their governments.

So fiscal rules are part of the ideological machinery that the conservatives use to keep governments from advancing full employment. Ultimately, full employment is seen not to be in the interests of some sections of society who can make fortunes despite there being significant labour underutilisation. Somehow this lobby has been able to convince us that keeping a large proportion (in Australian currently around 13 per cent; in the US around 17 per cent) is in the interests of society. As a result governments have not been under any political pressure to do anything about the blatant waste of human resources and potential that the neo-liberal policy framework has generated.

The Centre-Forum paper acknowledges that:

Policymakers face a number of potential trade-offs when drawing up fiscal rules. One influential analysis concludes that eight properties mark out an effective rule: it should be well defined, transparent, simple, flexible, adequate, enforceable, consistent and efficient. But it is impossible to design a fiscal rule that meets all possible requirements. A simple, transparent and enforceable rule such as ‘governments that fail to achieve a budget surplus over the year will be dismissed’ clearly lacks flexibility; however, if it were amended to permit some discretion for a crisis, it would no longer be well defined, simple or transparent.

The arbitrary nature of the fiscal rules in place in the Eurozone are clear. Germany and France were early violators of the Maastricht Treaty rules even before the crisis. The current EMU nations in breach of the rules would have found themselves in that state merely as a result of the automatic stabilisers so severe was the aggregate demand collapse. So the design of the Maastricht rules does not distinguish between discretionary changes in the budget to GDP ratio and those driven by the business cycle which are in most cases beyond the control of the national government.

Further, the ECB is now acting in total violation of the Lisbon treaty arrangements for the Eurozone (no bailout clauses etc) but at the same time are invoking the Maastricht fiscal rules as a way of penalising certain governments and forcing them to adopt harsh austerity programs. The inconsistency is palpable.

The point is that unless the rules are embedded in the constitution of a nation in an inviolate manner (free from further political manipulation) they will always be used to advance the ideological agenda of the dominant political coalitions.

As the Centre-Forum paper notes “(i)t is difficult to find evidence that any particular fiscal institutions have helped budgetary consolidation” which should be considered alongside the knowledge that there is also no evidence that monetary policy designed along specific inflation targetting rules has led to any differences in the trajectory of inflation (stability, persistence, level etc) when compared to nations who do not indulge in this approach.

Please read my blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion on this point.

In other words, the two main macroeconomic policy planks of the neo-liberal era are not supported by any robust and accepted empirical evidence. That should tell you all you need to know about the motivation behind this sort of policy advocacy.

The Centre-Forum paper then provides a review of the British experience with fiscal rules. At one point they once again display their ideological baggage when they claim:

A key objective of fiscal policy is to convince the markets that the government will not act in a profligate manner. This ought to produce lower borrowing costs.

That has only become a “key objective of fiscal policy” in the neo-liberal era which allows the (undemocratic and self-serving) bond markets the power to determine macroeconomic policy settings. An understanding of MMT tells you that the government can control its own borrowing costs any time it chooses (and even not borrow at all with no negative consequences). In that sense, what the bond markets think should never enter the government’s mind.

The key objective of fiscal policy is to ensure that public purpose is maximised and that requires high and stable levels of employment with secure wages and conditions. It requires a high standard of public service provision. It requires a stable financial system. The conduct of fiscal policy should only be considered in that light.

Another negative aspect of the move to impose greater fiscal constraints on sovereign governments has been the rise in importance of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) or as the Centre-Forum paper terms them Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs).

Governments claimed they had “run out of money” (given the impinging fiscal rule) and so sought to involve private funding of public infrastructure development. In this blog – Public infrastructure 101 – Part 1 – I provide some detail of these scams that have largely redistributed public spending to certain private sector corporations and paid much more than was necessary for the provision of the public infrastructure and services, which have often been of inferior quality.

PPPs are a total scam.

The Centre-Forum report claim that there:

… are some valid economic reasons for introducing private finance into the provision of public services: private sector incentives can improve efficiency.

The vast array of available empirical evidence does not support that claim as noted above and in the blog I referred to.

Finally, the latest conservative ploy is to suggest that politicians should not be responsible for the fiscal rules but rather “independent” bodies (such as the Office of Budget Responsibility in the UK). This call is consistent with the neo-liberal preference that central banks be “independent” of the political process.

As discussed above – this trend represents a further incursion on the democratic rights of the citizenry. It amounts to the installation of some panel of “philosopher kings” who know better and should determine outcomes independent of the democratic process. I do not support such arrangements. They are purely designed to advance the neo-liberal ideology and narrow sectional interests (which will rarely coincide with broader notions of public interest).

Anyway, I thought that discussion might broaden our understanding of fiscal rules from a MMT perspective. I also suggest you read the companion blog – Fiscal rules going mad … – for more background discussion on fiscal rules.

What happens when you impose an inappropriate fiscal rule

I built a simplified macroeconomic model to simulate some plausible scenarios. It is simple so that the essential points can be conveyed. I have much more complicated models available to me which will give the same result (more or less) but would take a book to explain and in the interests of being inclusive to all comers who visit my blog I don’t think that would be productive.

To show you a simple example of what happens when you impose a seemingly inoffensive fiscal rule here is a simple open economy macroeconomic model incorporating a spending system that allows us to simulate a collapse in aggregate demand (motivated by a sharp decline in private investment), a subsequent counter-cyclical response by the government, a violation of a simple (but current) fiscal rule, and then two policy paths: (a) no fiscal rule imposed; and (b) obey the fiscal rule and take a self-defeating path to scorching the economy.

We follow this economy for 10 periods starting with a private-debt motivated investment binge allowing growth to occur even though the national government is pursuing a budget surplus. The external sector is initially in deficit (exports are less than imports).

The structure of the simple model is described as follows with the national income-expenditure identity providing the overarching organising framework within which we propose some simple behavioural relationships (consumption, imports etc).

National income (GDP) is:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which means that total output and income (GDP) is equal to aggregate demand – the sum of the household consumption (C), private investment (I), government spending (G) and net exports (X-M). Exports (X) add to domestic spending while imports (M) drain it.

Disposable national income (Yd) is:

Yd = GDP – T

Taxation (T) is given by a simple proportional rule involving a simple tax rate (t) and income (GDP):

T = t x GDP

In the model the proportional tax rate is assumed to be 0.15, which means that the government takes out 15 cents of every dollar of national income generated. The small x just means multiplied by.

Private consumption (C) is determined by disposable income which is the net income (1 – t) x GDP:

C = MPC x (1 – t) x GDP

where MPC is the marginal propensity to consume (set at 0.8). In figures this means that:

C = 0.8 x 0.85 x GDP

which says that for every dollar of national income that is added total consumption rises by 0.8 x 0.85 or 0.68 – that is, 68 cents.

Private saving (S) is simply:

S = Yd – C

It is thus a residual of disposable income after aggregate consumption is determined. But as income goes up saving also rises and vice versa.

Imports (M) are also considered to be proportional to GDP so:

M = MPM x GDP

where MPM is the marginal propensity to import (set at 0.2), which means that for every extra dollar of GDP imports rise by 20 cents.

The spending aggregates I, G and X are assumed to be determined outside of the model by firms, government and foreigners, respectively. They are thus assumed to be exogenous – or given in any period. The other aggregates C and M are what economists call endogenous variables because they depend on the overall solution of the model – that is, we have to solve for GDP before we know their value but, in turn, the solution for GDP depends on C and M. This is the nature of a macroeconomic system – it is a simultaneous multi-equation system.

The spending multiplier is the extra spending that would occur when an autonomous expenditure source changes. So we ask the question: What would be the change in income if I or G or X changed by $1? I won’t derive the equation for the multiplier here for the sake of simplicity but its value is 1.9 and its equation is given with no further explanation as:

k = 1/(1 – MPC x (1-t) + MPM)

So the higher is the MPC the lower is the tax rate (t) and the lower is the MPM the higher is the multiplier. That makes sense because taxes and imports drain spending from the income generating system. So as income responds positively to an autonomous injection, the smaller are the drains via taxation and imports and the higher the induced consumption – the higher is the second round spending effect which then continues to generate further income increases.

Please read my blog – – for more discussion on this point.

For summary, the behavioural parameters assumed were:

- Marginal propensity to consume = 0.8 (so consumers spend 80 cents of every new dollar they receive).

- Marginal propensity to import = 0.2 (so for every dollar of national income generated 20 cents leaks to imports).

- Tax rate = 0.15 (so for every dollar of income generated 15 cents go to taxes).

- Spending multiplier = 1.9 (which follows from the previous three assumptions).

I could clearly make the model more complex but the results would not be very different. Some will suggest the model is overly simplistic because it is a “fixed price” model and assumes supply will just meet any new nominal spending. That is true by construction and is a reasonable description of the state of play at present.

There is no inflation threat at present due to the vast quantities of idle resources that can be brought into production should there be a demand for their services.

Some might argue the external sector is too simplistic and that the terms of trade (real exchange rate) should be included in the export and import relationships. In a complex model that is true but in the context of this model the likely changes would just reinforce the results I derive. There is no loss of insight by holding the terms of trade constant.

Some might argue that the interest rate should be modelled and I reply why? The implicit assumption is that the central bank sets the interest rate and it is currently low in most nations and has been for some years. With no real inflation threat, the short-term rates will remain low for some time yet.

As to long rates (and the rising budget deficit) – show me where the significant rises in budget deficits (for a sovereign nation) are driving up rates. They have actually been falling as a consequence of very strong demand for public debt issues (almost insatiable) by bond markets and the quantitative easing efforts of the large central banks.

For an EMU nation, long-rates are within the control of the ECB as has been demonstrated once it started buying government bonds in the secondary markets. So leaving monetary policy implicit and fixed in this model doesn’t lose any insight or “fix” the results in my favour.

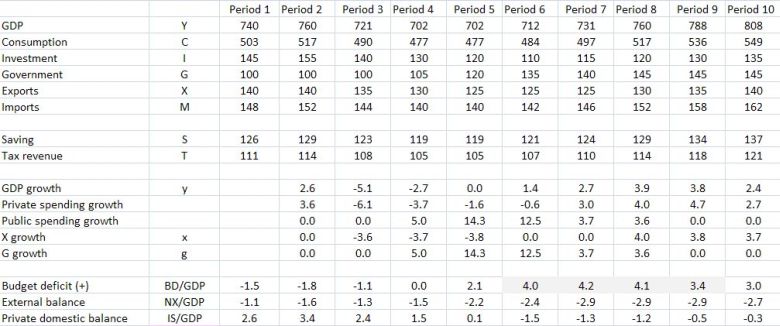

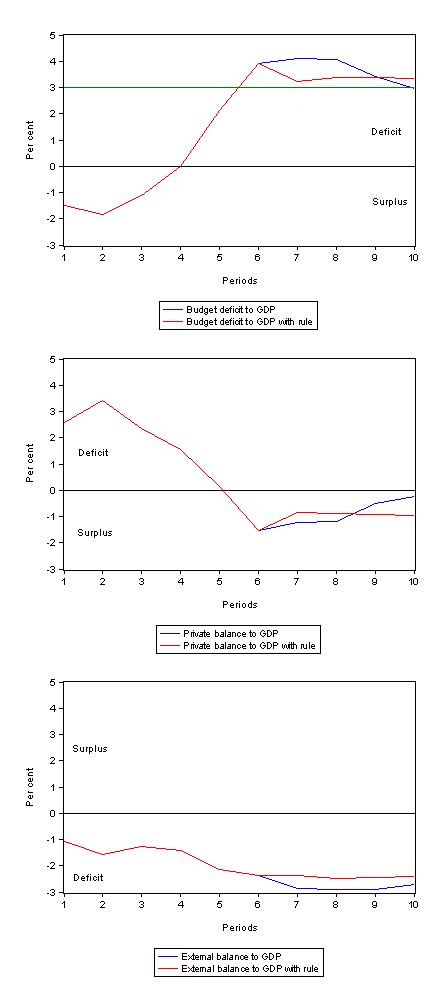

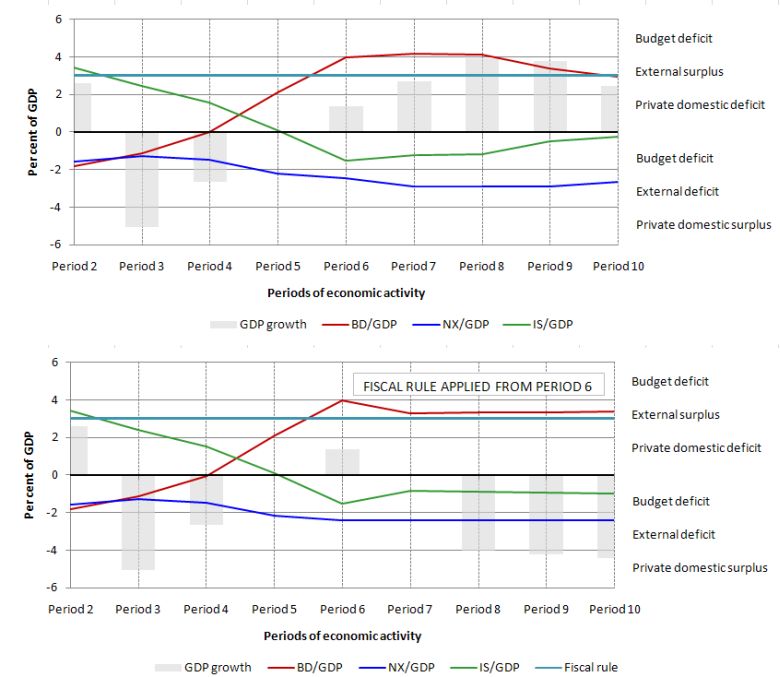

For those of you who love data as much as I do the following tables show the aggregates over the 10-period simulation for the simple economy model. Combining this information with the model specification you could easily construct your own spreadsheet although you can download mine more quickly – Clear the following file link sectoral_balances.

The top table is the situation when no fiscal rules are applied. It is clear that the government continues to support the economy as private spending recovers due to positive expectations associated with growth. The growth, in turn, allows tax revenue to eventually return and outstrip government spending and the budget balance goes below the “fiscal rule” limit by Period 10 but in an environment of growth in income and output.

This table shows the same economy but with the fiscal rule applied and forcing the government to cut back spending from Period 7 in response to the budget deficit exceeding the self-imposed 3 per cent of GDP rule limit. The differences between the economies shows up after this period and is stark.

The analysis that follows presents some salient graphs to highlight the differences.

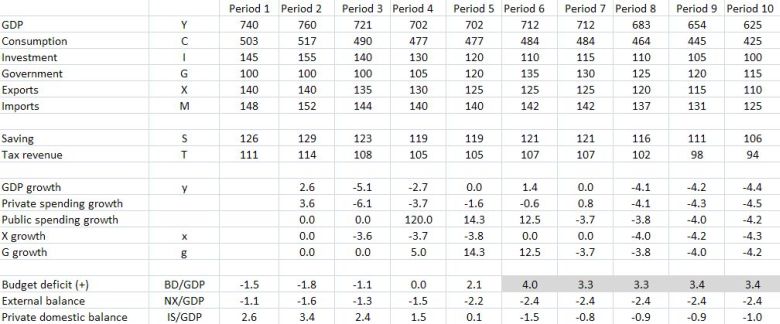

The first graph shows the evolution of the main macroeconomic aggregates: Private consumption, Private investment, Government spending, Private saving and Tax revenue with and without the fiscal rule being applied.

The economy is growing initially because the private sector is borrowing heavily to fund its spending (there is also an external deficit). As investment begins to collapse in Period 2 and beyond the economy quickly goes into recession (see accompanying tables and graphs).

The government responds by increasing spending and the budget moves into deficit as the increase in government spending is combined with a decline in tax revenue.

As the expanding budget deficit restores modest growth business investment also starts to recover in Period 6 and the consumption and saving continue to recover.

The blue lines (post Period 6) then chart what the response is when the government maintains fiscal support. All the aggregates improve and by Period 8 government spending growth flattens as the private spending recovery is entrenched.

The red lines (post Period 6) record what happens to the aggregates as a result of the application of the fiscal rule. You can see the sharp decline in discretionary government spending immediately starts to impact on its ability to collect tax revenue. This is because GDP (and income) growth declines again as the fiscal support is withdrawn.

The loss of tax revenue accelerates post Period 7 because investment, which was beginning to recover reacts to the loss of fiscal support and starts collapsing again.

You will also note that the decline in government spending is being outstripped by the decline in tax revenue which implies (see later graph) that the budget deficit is rising again despite the austerity measures.

Private consumption and saving also decline because of the double-dip GDP response (that is, national income declines again).

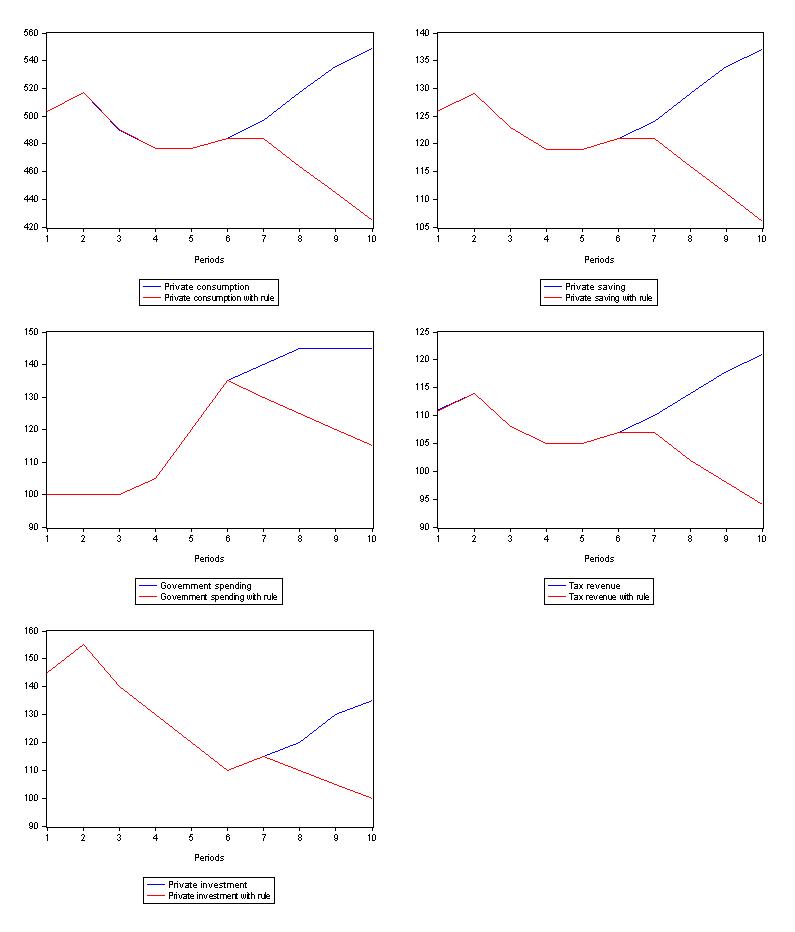

The next graph compares the evolution of the budget deficit as a percent of GDP (bar) superimposed on percentage GDP growth (line) with and without the application of the fiscal rule. The 3 per cent rule line is also shown. As the economy contracts due to the investment collapse in the second period, the budget quickly goes into deficit. The government continues to stimulate the economy as investment and exports fall and by Period 6 the budget deficit is in violation of the fiscal rule.

The responsible government response is shown in the left-panel – continuing to support growth which by Period 7 is also attracting a revivial in private investment spending. GDP growth continues as investment and exports recover and the budget deficit is below the fiscal rule limit by Period 10 and the economy is back on to “trend” growth as the fiscal contraction (the stimulus) declines.

The application of the fiscal rule is shown in the right-panel. The reaction to the budget deficit ratio going above the rule limit is to contract discretionary government spending and the impact is immediate on GDP growth. There is a slight improvement in the budget deficit ratio but the following period the economy double-dips as investment also declines again because firms realise that the dramatic withdrawal of the fiscal support to the recovery will damage their prospects of realising sales.

GDP growth continues to be negative as the recession deepens. The budget deficit ratio rises slightly as tax revenue collapses faster than the government is cutting its spending. The application of the fiscal rule fails to achieve any of the stated aims. The budget deficit ratio rise, GDP growth becomes negative and private investment declines.

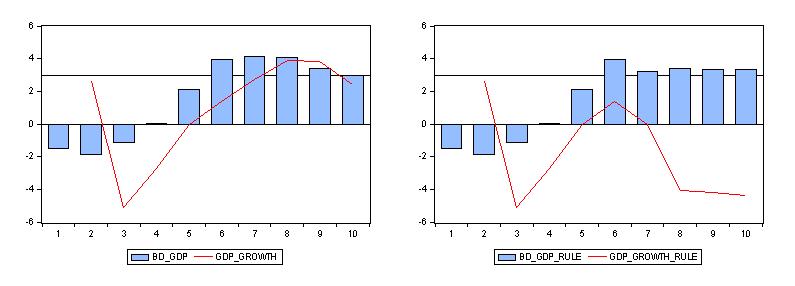

The next graph shows the evolution of the sectoral balances over the 10 periods. The sectoral balances are derived directly from the simple model above and are accounting statements that must be true.

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Combining that with our initial GDP expenditure identity (that is, equating the two different views of GDP) we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero and are described as follows (noting they are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP):

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

The evolution of the balances over the 10 periods is largely self-explanatory given the previous discussion relating to the other graphs.

The next graph shows the sectoral balances superimposed on real GDP growth for the scenario where no fiscal rules are applied (top panel) and where the rule is applied (bottom panel).

Once again the previous discussion should provide you with the explanation of what is happening here.

Conclusion

I typed this up while flying, sitting on the Eurostar and trying to sleep but not being able to! That is why it is a bit longer than usual. It is also a reflection of work I am doing for our upcoming macroeconomics textbook (with Randy Wray).

Anyway, more normal transmission will resume tomorrow.

That is (certainly) enough for today!

“Governments should not, however, push aggregate demand beyond the capacity of the economy to absorb it in real terms. But why would a sensible government want to do that anyway?”

Because you can create the illusion of wealth for a short period via asset inflation and credit expansion, and that buys votes. It happens every election.

Isn’t a fiscal rule just a misguided policy target? You can say ‘keep deficit at 3%’ or you can say ‘keep unemployment under 2%’. They are both targets.

[OT] Just spotted this:

http://pragcap.com/mmt-101

A good summary I thought.

Dear Neil Wilson (at 2010/09/30 at 19:41)

You asked:

Except that the government can keep unemployment under 2 per cent if it chooses but it may not be able to keep the deficit under 3 per cent. There are some things that a sovereign government can actually do.

best wishes

bill

Nice link Neil. Some good information.

bill you said:

“A national government in a fiat monetary system has specific capacities relating to the conduct of the sovereign currency. It is the only body that can issue this currency. It is a monopoly issuer, which means that the government can never be revenue-constrained in a technical sense (voluntary constraints ignored). This means exactly this – it can spend whenever it wants to and has no imperative to seeks funds to facilitate the spending.”

Under this definition, a country which runs a voluntary exchange rate peg (such as China) but is still the monopoly issuer of the currency would seem to be classified as a “sovereign” nation.

This is in contradiction to what you previously stated about Russia (which was a sovereign currency issuer with a voluntary fx peg) when the ruble crisis occurred. You claimed they were not a sovereign nation because of the voluntary constraints they had imposed.

Do you consider China to be a sovereign currency issuer?

bill said:

“The inflation of the 1970s was not the same beast that the deficit terrorists are telling us is just around the corner now. In the mid 1970s there was a huge price rise in oil as the OPEC cartel flexed its muscles and knew that the oil-dependent economies had little choice, at least in the short-run, but to pay up……the resulting wage-price spiral came directly out of the distributional conflict that occurred.”

Examination of the inflation data from the early 1970s will show you that inflation was on the rise well before the OPEC oil price rise in 1973. What caused this first spike in inflation?

An alternative theory to the one you have outlined above is that the oil price increase was actually in response to an already existing inflation problem which had been building throughout the late 1960s. In fact there was probably no single neat cause of the inflation of the 1970s, but a number of things played important roles, including monetary effects as well as the oil price increases.

As I understand it, the central concept of MMT is that a sovereign government has no barriers to limit its own spending in local currency given it can run whatever level of money supply it wishes. Interestingly the rating agencies do recognise this as they assign foreign and local (sovereign) ratings to issuing bodies (eg. the Australian states) which have the ability to tax and/or issue local currency.

The problem I see with MMT is that while in theory a sovereign nation can print all the money they want, in the real world no other nation would ever deal with that nation in LOCAL currency due to the unknown scarcity of that currency. Let’s say NZ suddenly adopted MMT policies and wished to set an unemployment target of 2% so they embarked on a job guarantee program which created an annual budget deficit of 20% of GDP to create and maintain this target.

Presumably the more the government expanded the money supply the lower the NZD would go against its trade partners. Would it be fair to say that the rest of the world would refuse to deal in NZD terms and as a result NZ companies would have to buy and sell goods based on USD or some other (gold?) standard?

Would it be naive to not think NZ inflation would skyrocket?

It just seems to me that MMT is a hard sell to the rational thinker due to the central theme of unlimited local money supply.

bill said:

“The only economic constraint that a sovereign government then faces is what we term the real constraint.”

“So the inflation barrier becomes the real constraint on government spending. This is obvious but then the question becomes what is that barrier?”

Bill, if you were put in charge of the federal budget, how would you measure the real constraint? How would you know whether or not you could increase government expenditure?

Would you advocate an inflation target?

This is one thing that a lot of MMT sceptics (like myself) would probably like to hear more about. What is the real constraint on government, how do we measure it?

Ray: “Printing money” is not so different from “debt-financed” deficit spending – and the lower interest rates are, the closer it becomes. Currency is just a 0% nanosecond maturity bond. They both have the same effect – being the only way net financial assets can increase. And everybody is deficit spending now, just not enough. MMTers key policy goals are demand support and full employment, not Zero Interest Rate / “print money”, which is more of a means than an end.

That “the unknown scarcity of that currency” would cause a plunge in its foreign exchange value does not follow at all. All (fiat) currencies trading against each other have unknown scarcity at present – and because so much money is bank money, not high-powered government money, not even the government controls the scarcity. So “Presumably the more the government expanded the money supply the lower the NZD would go against its trade partners.” is just not right. (Of course it would be right if NZ went nuts and mailed everyone a Trillion NZD check every day – but we are speaking realistically.) There’s a good chance the NZD would appreciate.

China followed a MMT / Keynesian recommended policy and had a nice big deficit to keep demand up and its economy humming.

So did Australia, relative to the US, for a while.

Is everyone abandoning the plunging renminbi? (Or wallpapering their houses with A$?) No, politicians are competing in demagoguery to denounce the Chinese for not letting the renminbi appreciate! (and the A$ is hitting highs against the US$)

Ray: in addition to the points made by Some Guy, the U.S. monetary base went up by an unprecedented 150% in 2009. The effect on inflation was around zero. See here:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/BASE

Conversely, inflation can get out of hand with money supply increases NOT being the main cause, as I think Gamma above suggests. It’s a bit more complicated than “print money and you automatically get a Mugabwe scenario”. But it’s not VASTLY more complicated. I could explain it all (as I see it) to an intelligent 17 year old in ten minutes.

Having said that, I agree with you that MMT is what you call a “hard sell” because of the money printing element. For that reason I’d like to see MMT advocates being a bit more careful what they say.

Hi, Bill- fascinating blog….

“At that time, neither labour or capital chose to concede and there were limited institutional mechanisms available to distribute the real losses fairly between all distributional claimants.”

“It is only during the neo-liberal period that this focus has narrowed to maintaining price stability.”

I would suggest that these are closely connected. It turned out to be quite difficult to tame inflation, at least given the intellectual mindset of the time, and we turned to rather brutal monetarism to kill the beast, as it were.

My question is.. what are the ideal institutional mechanisms that would resolve an external price shock? Government spending is rather sticky.. it can’t just renounce its economic demands to restore more of the pie to the private economy. So what would you see as an efficient way to mitigate a shock/inflation that is democratically coherent and leaves the government share of the economy reasonably stable? It sounds like the state has to engineer general deflation via tax rises/spending cuts to stop the spiral, while the private parties duke it out as they usually do anyhow. But that can be difficult to do in a political system.

I’m still convinced that the real constraint is the ballooning glut of savings that is added to with every deficit. Bill seems to regard adding to the glut of savings year on year decade on decade as some unquestionable duty we must all obey. If savings of high powered money are now >100x GDP and that is giving a damaging liquidity glut, then what on earth will it be like when savings are>1000x GDP. Remember much of that “GDP” is actually from the handling of those savings (the FIRE sector) so the ratio of real economy GDP to savings is even more out of whack.

stone– I agree that the savings (by the wealthy) – consumption ratio is out of kilter and contributed to our great recession. More of the fiscal stimulus in the U.S. needs to go to putting people back to work and boosting the income of lower and middle class Americans. Is this what you have in mind?

Ralph Musgrave: you say that “U.S. monetary base went up by an unprecedented 150% in 2009. The effect on inflation was around zero. ” My understanding was that the 150% increase in monetary base offset what otherwise would have been a huge asset price correction that would otherwise have wiped out the ramp up in asset prices that came from leveraged ponzi malinvestment upto 2008. Whilst it is true that consumer prices were not involved, it was a massive intervention to prop up those who leach off asset price inflation.

Gamma, the real constraints are the spare capital, labour resources when an economy is run below full potential, bar around 2% allowing for frictional job-change etc unemployment.

Read up the stuff on the Job Guarantee as this takes automatic fiscal stabilisers to their logical full extent.

Stone, how can the ‘ballooning’ private sector debt mountain be a sign of a ‘ballooning’ savings ‘glut’?

Stone:

“I’m still convinced that the real constraint is the ballooning glut of savings that is added to with every deficit. Bill seems to regard adding to the glut of savings year on year decade on decade as some unquestionable duty we must all obey. If savings of high powered money are now >100x GDP and that is giving a damaging liquidity glut, then what on earth will it be like when savings are>1000x GDP. Remember much of that “GDP” is actually from the handling of those savings (the FIRE sector) so the ratio of real economy GDP to savings is even more out of whack.”

Yes most of us, for some reason, like to build wealth (don’t you?), but it is not because Bill Mitchell asked us to do so.

Stone, don’t you think that as long as savings stay into their savings accounts there is not much pressure on the aggregate demand.

During periods when private sector decides to spend more than its income (spending from its savings or spending on credit) government should just act in contra balance to cool off the economy by going in to surplus (raising taxes and/or cutting spending).

Will Richardson says:

“Gamma, the real constraints are the spare capital, labour resources when an economy is run below full potential, bar around 2% allowing for frictional job-change etc unemployment.”

Yes I’m aware of what these MMT claims these real constraints are in theory. My question was: how do you measure them in practice? The unemployment rate, the underemployment rate rate, the inflation rate? I think you will have a very hard time coming up with a measure of the amount of “spare capital” (whatever that is) in the economy.

If MMT is going to argue that governments should abandon their the current budget constraint, which is based on a nominal amount of spending each year in favour of a constraint based on the level of “available real resources” in the enonomy then it’s necessary to specifically define how you measure this “real” constraint.

For example, do we say that governments can run deficits as long as inflation is below a certain level (what is this level)?

Or as long as unemployment is above a certain level (2%)?

Some combination of employment and inflation? What happens if high unemployment and high inflation occurs siimultaneously? Does this call for higher deficits to cure the unemployment or lower deficits to cure the inflation?

thanks Some Guy and Ralph M.

Just to clear a couple more things up.

As we know, exchange rates reflect currency pairs. The NZD vs the USD for example. Using NZ as a good example for the MMT experiment because it is small (ie. it is not the US or China which are hubs of world trade and political importance). Indeed pretty much all nations are experiencing huge deficit spending so there are few stressed currency pairs. Perhaps the AUD is becoming stressed due to its much higher interest rate structure and high commodity prices.

If the world suddenly recovered and governments all sought to balance budgets next year except NZ which decided to target 2% unemployment and double its budget deficit.

There is an assumption that GDP would spike higher due to the stimulus being at work in the economy with a likely inflationary effect as idle capacity was employed and resources became more scarce until industry would produce more (including perhaps net immigration if there were skill shortages).

I agree in this environment that the NZD would probably be neutral/higher against other pairs because the super strength of the economy would exert a positive NZD effect perhaps vs a negative effect due to the market disapproving of running such a large deficit in isolation to other nations.

If however, the NZ government ran this deficit funded program in isolation to other countries for 5 yrs, attained its 2% unemployment but GDP now moved back to flat/negative because let’s say commodity prices had flopped and inflation had risen to 10% due to resource scarcity (resources that NZ could not easily produce).

Under these conditions it seems likely the NZD would have a lot of downside.

How would MMT deal with these set of conditions given its central theme if to maintain its 2% unemployment target (assuming we call that full employment)?

thanks

RVM said:

“During periods when private sector decides to spend more than its income (spending from its savings or spending on credit) government should just act in contra balance to cool off the economy by going in to surplus (raising taxes and/or cutting spending).”

This statement is ridiculous ?

It’s governments going into surplus which forces the private sector to spend more than its income from savings and then resort to credit when the savings run out.

The reason why the private sector spends more than its income is to maintain as much of their current standard of living as they can as their incomes fall.

If the real-balance effect was in anyway significant you might have a point but there’s not an ounce of evidence to suggest that the real balance effects can counter the losses.

“What is the real constraint on government, how do we measure it?”

There’s no need to measure it if you have a JG – it is designed to be automatic. When unemployment rises, people will move to the JG. When private sector employment rises, people will move out of the JG. The scheme is designed to be as non-sticky as possible, with people allowed to move in and out of it relatively quickly.

Likewise, if there is high inflation there will be pressure for the government to cut spending in the private sector (not JG!). This then squeezes the private sector with fiscal drag, moves people back into the JG onto a fixed wage, and lowers overall wages. That’s how the JG controls inflation.

Of course, it’s difficult to predict exactly how much to cut spending, but the same goes for the NAIRU, the only other alternative out there. The JG method just means less human suffering.

On a broader point, I understand a lot of people’s reluctance to embrace MMT – there will always be difficulties in any economic framework, and they do need to be addressed. But you are all asking for it to be perfect, while we are straddled with a horrendously wasteful system right now. I find it hard to understand how you could believe MMT to be a worse system than the current paradigm, especially when the golden era of economics, the post war boom, was so much closer to the basic direction of MMT than anything nowadays.

stone:

The government can only really control the macroeconomic environment with any certainty, not the microeconomic one. Keeping the unemployment rate down while keeping the money supply fixed would require a very delicate microeconomic balancing act. It’s far easier and more predictable to deficit spend than try to do some tricky redistributions, or force people to cap their net savings. The above model should show what happens when the government ties it’s hands with meaningless nominal rules – it’s counterproductive and destructive. Why apply a constant money supply constraint? How could it possibly help?

A difficulty I have with MMT’s advocacy of fiat issue over borrowing as a method of “funding” deficits is not theoretical but programmatic. Let’s suppose that we have an economy with insufficient demand and higher unemployment and the government follows the course advised by MMT economists, of creating money sufficient to employ all the unemployed on a Job Guarantee on public works or similar. This brings the demand and employment levels up to full employment (which will be interpreted by investors as a Boom as Minsky said), workers move off JG employment into the revitalised private sector, etc. As a result private credit expands which expands the monetary supply (and its velocity, due to the boom). Since there was no government debt created, monetary policy is a less effective tool and government must then use fiscal policy (ideally, taxes targetted at overheated areas of the economy, speculation, the FIRE sector, etc) to withdraw money from circulation again to prevent inflation.

BUT, governments these days are extremely reluctant to raise taxes, particularly on boom sectors which a) have deep pockets with which to lobby politicians and other decision makers and b) can portray themselves in a compliant (because bought) media as the saviours and creators (rather than beneficiaries) of economic growth. Australians can observe the recent debacle of the attempt to introduce a Mineral Resources Rent Tax on a sector which was undeniably booming, benefiting from economic rent, and distorting the economy, which still nearly brought down a fairly well-functioning government. No Australian government is likely to do anything along those lines again for a generation or so.

It seems to me that the useful ideological function of deficits “funded” by government debt is that they give politicians an excuse/backbone to withdraw money from circulation during booms. The problem is that NAIRU/monetary policy ideas withdraw money in a way that creates unemployment and human suffering. What I would like to read (and I realise this is more of a political question than an economic one) is a clearer articulation of how MMT proposes to moderate boom conditions before they become over inflationary, which doesn’t necessarily rely on politicians having the courage to stand up to rent-seekers and speculators.

Dear Bill

I’m a bit lost by your reference to government options for dealing with cost-push inflation. It seems that you outline 3 alternatives: (1) the government can ratify the inflation by not reducing the nominal pressure, (2) it can break into the wage-price spiral by reducing its budget deficit, or (3) job guarantee.

Please can you spell out in more detail what you mean by (1)?

Many thanks

Grigory Graborenko said:

“:On a broader point, I understand a lot of people’s reluctance to embrace MMT – there will always be difficulties in any economic framework, and they do need to be addressed. But you are all asking for it to be perfect, while we are straddled with a horrendously wasteful system right now. I find it hard to understand how you could believe MMT to be a worse system than the current paradigm, especially when the golden era of economics, the post war boom, was so much closer to the basic direction of MMT than anything nowadays.”

Great post.

Neo-liberalism has failed to deliver for almost forty years and yet people are worried about MMT creating boom bust cycles, high interest rates, hyper-inflation, and higher taxes…blah blah blah.

Their real concern with MMT is that it will reduce the gap between the top and the bottom and that is the pill the neo-liberals cannot swallow.

JamesH: I think a far more effective backbone for the government would be the “arbitary” (in Bill’s view) fiscal rule that taxation has to match spending. However rvm says that most of us like to build wealth so that is reason enough to have taxes at a lower level such that savings build up. The idea that it is benign to let savings build up in bank accounts has been proved to be a dangerous mistake by the effect that the Yen carry trade had in the run up to the 2008 crisis. The Japanese ran deficits and Japanese savers kept the consequent savings as cash in Japanese bank accounts. The Japanese banks made short term loans to financial intermediaries who converted them into long term loans in USD, euros, GDP etc to fund the credit boom that lead to the bust. This caused $1T USD from the Japanese savers to help fund a moronic asset bubble outside Japan. This glut of Japanese savings did not cause the Yen to devalue because the carry trade loans were constantly rolled over so there was always more demand for more Yen. It also made profits for Japanese banks and that too helped support the value of the Yen. Deficit spending benefits (at least in the short and medium term) the nation that is deficit spending at the expense of the global economy. It is a bit like burning fossil fuels- the harm is not inflicted by climate change in the nation that is burning them any more than on the rest of the world. The attitude that people on here have that government printed money is a free lunch that we are all entitled to seems to me cruel and naive. No one ever gains financial power except at someone else’s expense. Money spent by the government to create aggregate demand can create real resources that would not otherwise have been made. Money remaining as savings due to government taxation not matching spending is financial power that would otherwise be in the hands of others.

Will Richardson- “Stone, how can the ‘ballooning’ private sector debt mountain be a sign of a ‘ballooning’ savings ‘glut’?” As Bill says government deficits equate to non-government savings. The private sector debt mountains are alongside private sector savings mountains that equal the private debts together with the accumulated government deficit spendings.

Grigory Graborenko says:

“There’s no need to measure it if you have a JG – it is designed to be automatic.”

“Likewise, if there is high inflation there will be pressure for the government to cut spending in the private sector…”

Grigory, you’ve contradicted yourself here. My question is: how does the government know what the real capacity of the economy is, so they know whether they can increase spending or have to decrease it?

Firstly you said there’s no need to measure it, everything is automatic, then in the next breath you say that the inflation rate is the measure.

I understand the theory that as private sector employment falls, people will move from the private sector to lower paying JG jobs, thus restraining inflation but maintaining full employment. But what causes the movement? Obviously less final demand, which could originate from less government spending or higher interest rates, both of which are at the discretion of government.

So what is the trigger to tighten? Inflation expectations? A current inflation rate above a certain level? What is that level?

Burk wrote: