I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Not the best way to keep interest rates down

The article by Fairfax economics editor Ross Gittins today (September 27, 2010) – How to limit the looming interest rate rises – is a testament to how ingrained the neo-liberal thinking is when it comes to discussing sensible economic policy. He argues that the Australian government needs to get back into budget surplus as quickly as possible and then continue to generate bigger and bigger surpluses and pay down all the outstanding public debt. Evidently this is because we are experiencing strong export conditions and face a dramatic inflationary threat. However, even if that is true (the boom and inflation threat) there are better ways to manage the adjustment process so that inflation remains stable especially when the private sector is still so heavily indebted (as a result of the last credit binge). The other policy options available to the Australian government clearly warrant continued budget deficits. The sticking point: Gittins and most other commentators think that when you have 13 per cent of your willing labour resources idle you are approaching full capacity. I consider that the fact that that proposition has currency is the ultimate evidence of the success of neo-liberalism in poisoning our judgement and distorting the policy debate and policy choices.

The article seeks to offer input into the growing discussion (cacophony) that monetary policy in Australia has to tighten significantly over the next 12 months to head off a looming inflation crisis.

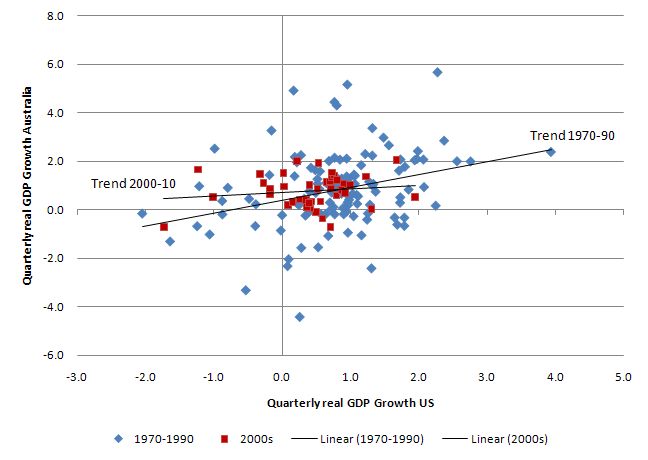

First, have a look at this graph that shows the relationship between quarterly real GDP growth for Australia and the US since 1970. The sample is divided into two periods, 1970-2000, and 2000-June quarter 2010. The black lines (demarcated for each sample) are simple regression lines. You can see that the relationship has become weaker between the two economies in terms of real GDP growth over the course of the 40 odd years shown.

The simple correlation for the first sample is 0.3 with the 1980s recording 0.5. The correlation for the last sample (2000-2010) is 0.2 and dropping below that towards the end of that period.

It used to be said that if General Motors (as a symbol of the US economy) sneezed, Australia came down with a heavy cold. This was in reference to the empirical reality maintained over a long period of time that Australia’s business cycle was highly synchronized with the US business cycle.

The reality now is different and Australia is no longer as directly dependent on the US growth fortunes. But we are now more increasingly an Asian-nation and that means the data will increasingly show tighter synchronisation with the fortunes of China and to a lesser extent India.

The first signs of that were the fact than in 2001, while the US went into recession Australia largely avoided a serious slowdown in economic growth. In the previous two US recessions (1982 and 1991) Australia suffered severe simultaneous downturns.

The most recent evidence is that the Australia was among the few advanced nations which did not experience a “technical” recession in the last few years. Australia had one negative quarter of real growth only. Further, while the rest of the world is labouring with low growth rates in their recoveries and teetering on going backwards, the Australian growth rate is near recent-past trends (which is still below what it should be to provide enough jobs) and we are enjoying very strong terms of trade as a result of China’s demand for our commodity exports.

All the policy talk in Australia is currently about the threat of inflation whereas the debate in the northern hemisphere is the reverse.

Even though Japan is still Australia’s major export destination (19.3 per cent of total exports in 2007-08) compared to the US (5.9 per cent) and China (14.9 per cent), the latter market has been growing at 18.1 per cent per annum while the Japanese market has been growing at 7.1 per cent.

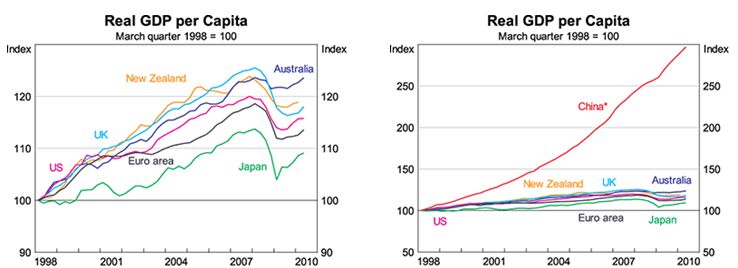

The following graph is compiled from a speech made by the Governor of the RBA last week. The left-panel shows real GDP indexes for selected advanced economies and then the right-panel superimposes China onto the other data. The idea is that the rapid growth that China is experiencing is giving us a ticket to ride away from the economic cycles currently being endured by other advanced nations.

Very rarely however, do you read or hear anyone point out that it was their aggressive fiscal policy response that kept the Chinese economy growing throughout the turmoil.

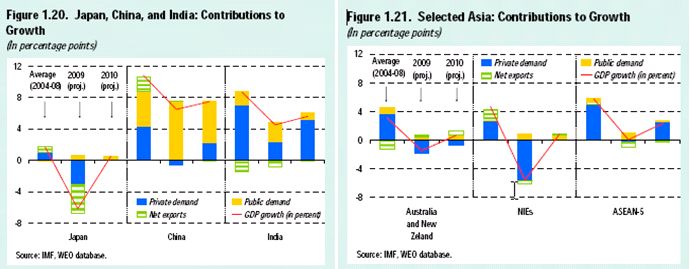

In this blog – Where the crisis means death! – I provided some IMF data from their Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific Report 2009 that split the contribution to growth of public demand (net government spending), private demand and net exports for some Asian nations from 2004 to 2010.

China stands out. Most people think of China’s growth coming from its burgeoning export sector. But it has a very strong domestic economy and a large public spending program – its called “nation building”.

Nations need to be continually built and the comparison between China’s performance with Japan (with virtually no public sector) and the performance of Australia and New Zealand, which have only minuscule growth originated from public spending, is compelling.

The IMF Report noted in that:

In China, GDP growth will also slow down notably from the average pace of the recent past. Still, the aggressive policy response is expected to support domestic demand and maintain growth at rates close to the level authorities consider necessary to generate jobs consistent with social stability. In particular, the massive program of public investment initiated late last year is expected to compensate for the decline in private investment and absorb productive resources no longer utilized in the tradable sector.

The graph highlights, in my view, the importance of very large fiscal interventions. My Chinese friends tell me there is no discussion over there about the country drowning in debt and all of that nonsense. They know full well that they are sovereign in their own currency and can deficit spend to further their sense of public purpose (which may not be my sense).

While I disagree with the Chinese government approach to freedoms etc, much of the spending is developing public infrastructure (for example, world’s best train systems, better housing, first-class schools and universities) which will provide a rising material standard of living for their people (as seen in the fantastic growth in real GDP per capita in the above graph.

What they appear to have developed is a more sophisticated understanding of the opportunities that they have as a monopoly supplier of their currency than the western governments have demonstrated. And they are taking those opportunities more than other nations around them that are caught in and are being choked by the neo-liberal web imposed on them by the advanced nations.

In his speech, the RBA Governor said that the Australian economy may face some risks in the coming year:

Possible candidates might be a return to economic contraction in the United States, or a bigger than expected slowdown in China, or the resumption of financial turmoil that abruptly curtails access to capital markets for banks around the world and damages confidence generally. But if downside possibilities do not materialise, the task ahead is likely to be one of managing a fairly robust upswing.

In that context, he outlined what he claimed were the objectives of monetary policy. But these objectives have clearly changed over the last several decades.

The Reserve Bank of Australia was legally constituted to pursue full employment as one of its three goals (price stability and general welfare being the others). The functions of the RBA Board are set out in Section 10 of the Reserve Bank Act 1959. However, the RBA has been significantly influenced by the NAIRU concept and it conducts monetary policy in Australia to meet an openly published inflation target. The persistently high unemployment in Australia over the last 35 years, would suggest that the RBA has not been working within its legal charter.

However, circa 2010-neo-liberal style these objectives have now become:

… to preserve the value of money over time and to try, so far as possible, to keep the economy near its full employment potential. Over the long run, these are mutually reinforcing goals, not conflicting ones.

So he is invoking the NAIRU-dogma that keeping inflation low even at the expense of rising unemployment will eventually lead to full employment. In other words, there are no real impacts on pursuing an inflation-targetting regime.

In September 1996, the Treasurer and Reserve Bank Governor issued the Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy, which set out how the RBA was approaching its goals, and articulated that inflation control was its primary policy target (RBA, 1996: 2).

The RBA emphasises the complementary role that “disciplined fiscal policy” has to play in an inflation-first strategy. There was no discussion about the links between full employment and price stability except that price stability in some way generated full employment even though the former required disciplined monetary and fiscal policy to achieve it. In a stagflation environment if price spirals reflect cost-push and distributional conflict factors the RBA will always have to control inflation by imposing unemployment.

The RBA answers this apparent contradiction by arguing that the trade-off between inflation and unemployment is not a long-run concern because, following NAIRU logic, it simply doesn’t exist. A senior official (Malcolm Edey) in 1999 said:

Ultimately the growth performance of the economy is determined by the economy’s innate productive capacity, and it cannot be permanently stimulated by an expansionary monetary policy stance. Any attempt to do so simply results in rising inflation.

The empirical evidence is clear that the economy has not provided enough jobs since the mid-1970s and the conduct of monetary policy has contributed to the malaise. The RBA has forced the unemployed to engage in an involuntary fight against inflation and the fiscal authorities.

The NAIRU-discourse was the result of a paradigm shift in the way that the concept of full employment was constructed. In the 1940s and early 1950s the emphasis was in ensuring that there were enough jobs for all those who desired and were willing to work.

By the late 1950s and into the 1960s, the obsession with inflation was mounting (the Phillips curve era) and so full employment became tied with some desirable inflation rate (and a trade-off between unemployment and inflation was conceived as being something policy makers could exploit).

This concept of full employment was challenged by expectations-augmented Phillips curve of Friedman and Phelps which emerged in the late 1960s. This monetarist-type attach established the concept of the natural rate of unemployment (NRU). Allegedly, the inflation-unemployment trade-off was, in fact, a trade-off between unemployment and unexpected inflation.

When all expectations are realised, the NRU is the only unemployment rate consistent with stable inflation. My own work has shown this to be a major theoretical break from the existing Phillips curve orthodoxy because the causality from quantity disequilibria to price changes was reversed. Unemployment was considered voluntary – the outcome of optimising choices by individuals between work and leisure. Accordingly, discretionary aggregate demand management was considered futile and so the link between the use of budget deficits to restore deficient demand and the maintenance of low unemployment was abandoned – Says Law was restored.

Full employment occurred at the NRU even if that involved considerable unemployment. In some of my earlier published papers I describe how Australian economists defined full employment in the mid-1980s as being equivalent to an 8 per cent unemployment rate. According to the theory, the NRU could only be reduced by microeconomic changes if it was considered to be excessive. As a consequence, the policy debate became increasingly concentrated on deregulation, privatisation, and reductions in the provisions of the Welfare State. Unemployment continued to persist at high levels.

The NRU is closely related to the concept of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU), first proposed in 1975. So the claim is that there the NAIRU is such that as long as the unemployment rate is above it, there will be a deceleration of inflation.

It was also claimed that the NAIRU could only be reduced by structural policies and that attempts to maintain unemployment below this “natural rate” would only cause inflation.

The resulting “fight-inflation-first” message has dominated public policy makers since the first oil shocks of the 1970s, and has exacted a harsh toll in the form of persistently high unemployment. Full employment as initially conceived was abandoned at that time.

The move to inflation targeting on the back of an overwhelming faith in the ‘NAIRU ideology’ marked the final stages in the evolution of an abandonment of full employment. The modern policy framework is in contradistinction to the practice of governments in the post World War II period to 1975 which sought to maintain levels of demand using a range of fiscal and monetary measures that were sufficient to ensure that full employment was achieved.

The way that the RBA reconciles their “failure to maintain full employment” – that is, their legislative failure – is to redefine the problem away. That is, full employment is now alleged to be around 5 per cent. In the period after WW2 and up until the 1970s, unemployment rates were usually below 2 per cent and that is what we considered full employment to mean.

We also didn’t have any significant underemployment during that “full employment era” whereas now underemployment is running at 7.5 per cent (and that is a conservative estimate).

For more discussion of the NAIRU please read this blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! .

The empirical world doesn’t support the RBA Governor’s faith in the ephemeral nature of the costs associated with maintaining high unemployment to discipline price inflation (the NAIRU unemployment buffer stock strategy employed by the RBA).

My own work and that of others has categorically shown that the so-called sacrifice ratios (the real GDP cost of reducing inflation by 1 per cent) are high and persistent. The long-term losses of this policy strategy that emphasises inflation-first monetary policy management are very significant.

Please read my blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion on this point.

Anyway, that was all background to my brief discussion of Ross Gittins article, which generalises to a broader discussion of the use of fiscal policy.

Gittins worries that the RBA is going to have to start increasing interest rates – as early as next week – because:

… the economy is already growing at trend (3.3 per cent over the year to June) with little spare capacity (the unemployment rate is down to 5.1 per cent) … What’s worrying the Reserve is that, whereas business investment spending has been flat … the survey of firms’ capital expenditure plans suggests it could grow by as much as 24 per cent in nominal terms next financial year, with mining accounting for most of that.

Although sky-high commodity prices will be feeding incomes and flowing into consumption, it’s such huge rates of increase in physical investment that will make the resources boom so big and so potentially inflationary – “the largest minerals and energy boom since the late 19th century”, according to Stevens.

Stevens is the RBA Governor.

In this blog – Redefining full employment … again! – I discuss the absurdity of this construction of full employment.

On July 19, 2010 I wrote this blog – Full employment apparently equals 12.2 per cent labour wastage – which highlighted how much ridiculous claims that the Australian economy was at full employment were. The total labour underutilisation rate has risen since then as the rate of growth has not been sufficient to absorb the growth in the labour force.

So Gittins is very much in the NAIRU-denial camp.

Gittins claims that “it’s investment booms and improvements in the terms of trade, rather than recessions, that pose the greatest challenges for macro-economic policy – mainly because mismanaged booms invariably lead to recessions.”

The last two major recessions were poorly managed by the government who didn’t rise to the policy challenge and led to very sharp increases in unemployment. The residue of that labour underutilisation has never been successfully addressed by policy.

If you deny that such waste is a problem then it follows that managing a recession and its aftermath is not a big “challenge”. But that is just NAIRU-style reasoning.

His principle argument is that in the past resource booms governments have been lax in their vigilance of the inflation pressures. Then they:

.. panic, jam on the brakes, keep raising interest rates because they don’t seem to be working and eventually the economy runs off the road and crashes, hurting passengers and bystanders alike.

He considers the RBA won’t let “that happen this time” and will push rates up in advance of any realised inflation spiral.

He lists several possible limiting factors. The appreciating exchange rate that is squeezing “non-mining export and import-competing industries” and suppressing wages growth.

Further, consumer spending is flat “as households seek to get on top of their debts”. He claims that:

The ratio of household debt to disposable income has been steady for the past few years and it would be nice to see it falling over coming years. But how long it will take for the boom to overwhelm households’ present restraint is anyone’s guess. Mine is: not long.

Despite his claim, the ratio of household debt to disposable income has not been steady over the last few years as my graphs later will show. It has continued to rise even during the slowdown. There has to be serious support for households to rather significantly reduce their debt exposure. This implies budget deficits as I will explain.

Gittins disagrees and suggests the best way to ease the pressure on interest rates is for the government to run ever increasing surpluses.

The answer is for Labor to continue its present strictures on tax cuts and spending, allowing the budget surplus to grow ever-bigger each year, something that could be readily justified to the mesmerised punters as needed to pay back our supposedly stupendous public debt.

So first of all tell lies to the “mesmerised punters” who have been assaulted with prior lies about the “supposedly stupendous public debt” which appears to be a fine goal for a national government to pursue!

But the logic of this policy approach is all NAIRU. I accept that the central bank is likely to keep pushing rates up now given its own NAIRU outlook. But that does not mean that the government has to run surpluses. Deficits are no threat to the inflation rate while there is a vast amount of idle labour.

Persistent labour wastage means that aggregate demand is not growing strongly enough. Involuntary unemployment is defined as labour unable to find a buyer at the current money wage. In the absence of government spending, unemployment arises when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to spend less of the monetary unit of account than it earns.

Nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless they somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save and increase spending. The non-government sector depends on government to provide funds for both its desired net savings and its tax obligations. The private sector cannot by itself ‘net save’ because saving is a signal to lend and so savers are always in an accounting sense matched by a borrower.

To obtain these funds, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed currency units. This includes, of-course, offers of labor by the unemployed. Thus, unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

So normally, a government deficit will be required to ensure high levels of employment.

Persistent budget surpluses also force the private sector into increasing indebtedness. The sectoral balances (private, public and external) in the national accounts are:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

Equation (1) says that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G - T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. What happens to the public surplus? It is often argued that 'public saving' can be used to fund future public expenditure. This is Gittins logic. But public surpluses do not create a cache of money that can be spent later. Government spends by crediting a reserve account. That balance doesn't 'come from anywhere', as, for example, gold coins would have had to come from somewhere. It is accounted for but that is a different issue. Likewise, payments to government reduce reserve balances. Those payments do not 'go anywhere' but are merely accounted for. A budget surplus exists only because private income or wealth is reduced. In an accounting sense, when there is a budget surplus then there is a destruction of base money and/or a destruction of private wealth. The budget surplus may be applied to running down debt (that is, forcing the private sector to liquidate its wealth to get cash) but this strategy is finite. The alternative is to destroy liquidity (debiting reserve accounts) which is deflationary. The weaker demand conditions would force producers to reduce output and lay-off workers with rapid increases in joblessness. Investment irreversibilities driven by uncertainty of future demand conditions then retard capacity growth and prolong the downturn. The pursuit of public surpluses necessitates an increase in the net flow of credit to the private sector and increasing private debt to income ratios. Is a threshold reached where the private sector, by circumstance or choice, becomes unwilling to maintain these deficits? If so, then the reliance on rising indebtednesses to underwrite private spending is ultimately, an unsustainable growth strategy. The private sector (and the spending the debt has supported) becomes increasingly vulnerable to interest rate increases, declining asset values and lost incomes. We examine the dynamics of this trend to fragility next. The sectoral balance model also suggests that the private domestic sector can save overall even with budget surpluses if net exports are strong enough. This is what Gittins is thinking will happen perhaps. But history tells us that it is highly unlikely that net exports will contribute enough to real GDP to achieve this. Please read my blog - A mining boom will not reduce the need for public deficits – for more discussion on this point.

However, our external position is unlikely to move into surplus, which means that public deficits will be required to “fund” the private domestic surpluses.

Commentators who do not recognise these intrinsic relationships that are embedded within our national accounting structure are prone to make erroneous conclusions and in doing so just become passive mouthpieces for the neo-liberal agenda.

The mining boom if it happens will not create an external surplus on the current account. Norway’s oil resources are driving a strong external surplus. But the mining sector is not large enough in Australia to do that.

So if our external position remains in deficit, which it surely will (especially as growth will stimulate imports) – then we know from our national accounting that if the government moves into surplus by dint of the growth in revenue from the boom and discretionary cuts in its spending, then the private domestic sector will be in deficit – spending more than it earns.

That is exactly what we need to avoid because household balance sheets are still fragile from the debt-binge of the last decade. In other words, if the external sector remains in deficit, the only way the private domestic sector will achieve a surplus position, is if the government sector continues to run deficits.

Further, by choking off private spending via tax rises the government can reduce the pressure on imports which will give more scope for exchange rate to provide an inflation-dampening impact. At the same time, the government can continue to deploy real resources not being absorbed by the mining boom via its own spending choices.

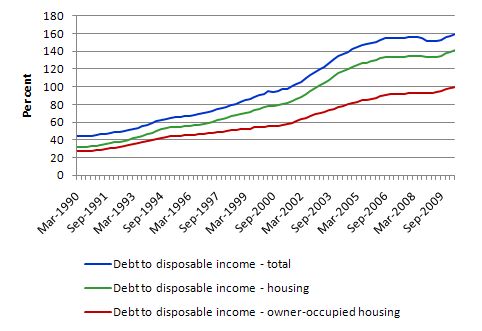

It is clear that the Australian household sector is now carrying record levels of debt, a lot of it attributed to an over-investment in housing. The following graph uses RBA data – Household Finances – Selected Ratios – Table B21.

In March 1990, the ratio of Debt to disposable income was 44.7 per cent with housing debt being 32.2 per cent of disposable income and in terms of debt carried by owner-occupiers the ratio was 27.6 per cent.

By June 2010, these ratios were 159.2 per cent (total), 141.6 per cent (housing) and 99.1 per cent (owner-occupied housing). So most of the debt is owed to banks, usually for dwelling mortgages, with the growth facilitated on the supply side by the machinations of the financial engineers in the form of securitisation. The misnomer for the aggressive behaviour of these engineers is “financial innovation”.

The pursuit of budget surpluses between 1996 and 2007 exacerbated the situation because it gave the banks an incentive to innovate because the supply of risk-free interest bearing securities (public debt) decreased and asset-backed bonds became the best fixed interest security available.

The standard line in defence of these trends is that the household debt growth reflects spending based on increasing wealth. However, household assets have grown more slowly than household debt. The two other realities are that a vast majority of the assets are not liquid (real estate and superannuation and an increasing proportion of the “wealth” is in the form of speculative assets (shares and other investments).

So while in theory a household facing a major crisis could clear a substantial proportion of their debt obligations by liquidating the reality is different. In the event of a crisis, some of these liquid assets would lose value significantly.

On a per household basis, the problem of realisation is also demonstrated by the falling equity in real estate assets as a result of debt outstripping the value of the real estate owned. Thus the portion that can be liquidated is steadily being eroded. However, it is problematic to seek security by examining what might be possible in a ‘fire sale’.

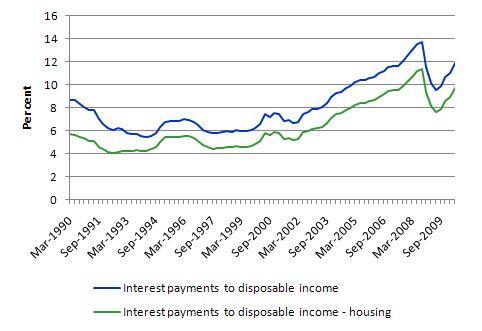

What has been the trend in debt servicing capacity over the same period? The interest payments to disposable income ratio is shown in the following graph. Clearly, the capacity to service debt by Australian households is deteriorating.

The lower interest rates during the early period of the crisis eased the pressure a little but that trend is now reversing.

Overall, the household sector in Australia remains highly vulnerable and has to continue to restructure its balance sheet (overall) to ensure a more stable future.

It was also interesting that a report just released by Goldman Sachs property division – A Study On Australian Housing: Uniquely Positioned Or A Bubble? says that:

Australian house prices are 35 per cent overvalued

Their lower bound estimate “currently suggests that house prices are 24 per cent overvalued.” Whichever measure you adopt, the forecast is that a significant fall in Australian housing prices is due in the next three years.

The Sydney Morning Herald today (September 27, 2010) carried a story – Australian property is overvalued, and time is running out to bring down debt.

The article reports on ABS data which shows that housing prices in Australia have risen by:

… a whopping 18.4 per cent over the past year, 50 per cent over the past five years, 165 per cent over the past 10 years, 246 per cent over the past 15 years and 289 per cent over the past 20 years.

The SMH article also recognises that “Australians are now so geared with debt that it’s not possible to inflate our way out of the situation with higher house prices” at the same time as we are “suffering from a chronic housing shortage, which is set to worsen over the next two years as demographic demand outstrips supply.”

Part of this shortage has been the lack of investment in public housing as the neo-liberals influenced governments to cut back on public infrastructure investment over the last 25 years.

The SMH article paraphrases the GS Report which suggests the motivation of the latter:

The prospect of an abrupt and sustained decline in trade with China or an oversupply of resource commodities in world markets may be the catalyst for a fall in house prices. Tighter fiscal policy and “jaw boning” property owners with higher interest rates may prevent households from becoming even more exposed in the face of a downturn … Government policy should aim to bring forward budget surpluses and bank them in a sovereign wealth fund to smooth the rough ride ahead.”

So yes, squeeze the economy and spend the “surplus” on financial asset speculation which GS can help organise! That is just the sort of policy emphasis one would expect from GS.

But running surpluses as noted will not help the private sector reduce its overall indebtedness unless net exports provide a much greater contribution to real GDP growth than has been the case in the past (and during past growth booms).

The other problem is that there needs to be a massive increase in public housing to address the appalling housing affordability problem being driven by the shortage of housing stock.

It is clear that our fiscal approach to housing is all wrong.

First, the Australian government should eliminate the tax advantages that are provided to a minority (of better-off Australians) in the form of negative gearing (writing off losses on investment properties against income). This would force the investors to bear all the costs and improve the assessment of capital gains.

Second, we should tax the capital gains more rigorously to mostly eliminate the speculative market for housing. People will still compete for the scarce assets but within a much different costs and benefits environment which would put a brake on the speculative excesses (for example, owning multiple properties).

Third, a crucial point about the arguments surrounding rental property availability, is that they usually ignore the provision of public housing and never consider the obvious solution for low-income earners – a publicly-provided fund for house purchase.

Public housing has been subjected to the neo-liberal attacks on government spending over the last 20 years or so and waiting lists remain very high. There is a huge shortage of low-end housing stock in Australia as a result.

According to the Commonwealth State Housing Agreement national data published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (latest report covers 2007-08 and published January 2009), there were around 389,000 social housing dwellings in Australia. Social housing includes public housing, government-owned and managed Indigenous housing, public-subsidised community housing and various types of crisis accommodation.

The latest data says that there are still more than 225,000 people waiting for social housing in Australia. By far the largest component of social housing (around 85 per cent) is public housing. Over the last decade or so there has been around a 5 per cent drop in the provision of public housing as governments have adopted neo-liberal strategies to force more private ownership/rental. As at 2007-08 (latest estimates) there were 178,000 people waiting for public housing and the delays can be years.

Again housing authorities have toughed eligibility criteria and reviewed the status of many residents deeming them no longer eligible. This has reduced the waiting lists by around 16 per cent but only by reducing demand.

I consider that the housing problems have been seriously exacerbated by the poor design and implementation of fiscal policy in Australia. In that regard, I believe an appropriately designed taxation system with targetted policies to stop housing speculation would be far more efficient at controlling asset price bubbles than using the blunt end of monetary policy.

Monetary policy is a very inefficient policy tool. It cannot discriminate across regional space. We have seen that in recent decades a booming capital city can be accompanied by stagnant regional and remote economies. And the considerable regional disparities in economic performances have persisted even during the growth spurt.

In cases like this, when, say a major city (for example, Sydney) is booming and housing prices are escalating, increasing interest rates impacts severely on the stagnant areas of the country.

This would not be the case using a well-targetted fiscal instrument – mostly in the form of specific taxation measures that can discriminate by region and demographic-income-property cohorts. You can never get that richness in policy design using monetary policy.

Further, if public housing is considered undesirable as a solution the federal government (with some constitutional reforms) could set up a fund to allow access to cheap mortgage instruments to low-income families and allow them to purchase housing (publicly- or privately-provided) with minimal distortion to the price distribution. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) tells us that the federal government can always afford to do this.

But this doesn’t mean we should be tightening fiscal policy overall. That is the beauty of fiscal policy – you can tighten and squeeze certain spending segments yet maintain overall support for economic growth (running deficits overall).

Please read my blog – Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

The policy debate is so confined to supporting rising interest rates and budget surpluses at the moment at a time where the government should be creating more than 1/4 million public houses and providing deficit-support to the growth process to allow the non-government sector to continue to pursue balance sheet restructuring.

The last thing that is required right now is to re-create the conditions that means that growth is reliant on on-going increases in private sector indebtedness.

That is enough for today!

I guess the lucky country is still lucky… For now!

Their flawed neo-liberal economic policy is made to look smart by so called “reckless” deficit spending of another country. Communist to boot….. What rich irony.

They have a once in a lifetime opportunity to stay lucky. With slight adjustment to policy settings they could (hopefully) slowly deflate the housing bubble. Then, by hanging onto the tails of Chinese Cheongsams and running a job creation budget surplus. They could just about avert a serious recession. It could be a masterstroke. Nobody outside Oz would even notice what happened.

The problem is. The solution requires a fundamental change in ideology. Can’t see Swan, Gillard and Glen changing spots anytime soon. Extend and prentend are the marching orders of the day……..Bill for PM.

Bill, satisfying the “desire to net save” seems to be the crucial justification for long term global deficit spending versus matching taxation to the required government spending. I wish that concept was expanded upon more rather than just flatly stated in each blog (I appreciate your bog is not a request show!). It is clear to me that people want and should have a buffer of savings but I don’t see why the size of that buffer in aggregate across the global economy should increase year on year. Some people will be building up their savings when they are earning (or otherwise appropriating 🙂 ) but not spending so much and others will be drawing down their savings when they are spending more than they earn. To my mind there is an optimal ratio of global money in savings versus global money being spent on consumables (goods and services). Continuous deficits just cause the global economy to stray further and further from that optimum and to me at any rate that appears to be the key driver of world poverty.

“The policy debate is so confined to supporting rising interest rates and budget surpluses at the moment at a time where the government should be creating more than 1/4 million public houses”

Housing affordability is indeed probably the single biggest challenge for the government thesedays and the RBA’s imminent tightening(s) seems at odds with tackling this problem as already high private debt levels will face higher funding costs. I wonder if there was any cost/benefit analysis done within the government at the time when the Building the Education Revolution was initiated vs immediately building hundreds of thousands of houses in regional Australia and offering them for free to those who might want to relocate away from cities.

Unfortunately the political debate throughout the election by politicians and economists has been this irrational obsession with producing a budget surplus at any costs and as soon as possible. Remarkable, even for a capitalist like myself to understand.

The RBA is given the responsibility to maintain a 2-3% inflation target over the business cycle and this is being threatened again (notwithstanding the good Q2 outcome). In this regard it has little choice but to hike. I see few alternatives given this mandate and the strength of the export sector. If the government got their act together and imposed a sensible mining profits tax then the RBA’s work would be easier as this would be a better way to help contain the 2-speed economy and return some equity to the public.

Andrew Wilkins says:

Monday, September 27, 2010 at 19:21

“Their flawed neo-liberal economic policy is made to look smart by so called “reckless” deficit spending of another country. Communist to boot….. What rich irony.”

AW, we still need to be cognizant that much of China’s sudden rise is still as a result of oppressive slave-like labour conditions. So they might be getting paid 2 bucks now (and 5 bucks tomorrow) rather than 2 bob last decade which is magnifying incomes many fold. Add into the equation the new hospitals, roads, schools etc and there is doubtless a boom in standards of living.

Now look at the minimum wage in Australia, US etc and we will never be able to compete with China but I’d like to think we are a more just country with regards human rights.

The Chinese government now reflects a sort of market communism which is good for its citizens however I’d be cautious in pointing to this as a model economy just yet given how far things still need to evolve.

Stone: I don’t think it’s much use criticising the private sector for wanting to save more than you or anyone else thinks is “optimum”. The brute reality is that if the private sector wants to save, it will try to, and unless government supplies cash to satisfy the desire for cash savings (or bonds), unemployment will ensue.

Also I don’t see why it desperately matters whether average savings per household are $500 or $5,000. As long as households can manage their affairs efficiently on either figure, who cares?

You could argue that the level of saving in some countries (notably Japan) is ridiculously high and this is a potential source of instability in that if Japanese households all decided to spend half their savings at once, the result would be chaos. On the other hand even in countries which are notoriously poor savers (Anglo-Saxon countries), if every household went wild with their credit cards at the same time, the result would be equally chaotic.

Ray,

I was more thinking we can ride the wave of mineral exports to China. While building up the non mining economic sectors, in a manner that creates sustainable jobs. Investments have to avoid pumping the housing bubble further, as this is largely unproductive and IMO unsustainable.

I am no fan of China’s social policy. From my personal experience, I found China a hotbed of misery and cheating.

The appalling reduction in spending on public housing, especially under Howard, did have its effects and on a human level they are quite terrible. Figures in the Productivity Commissions Report on Services 2007 show that the Libs progressively decreased investment so that by 2005-06 spending on public housing was $400 million per annum less. Not only were new houses not built but existing Australian stock went down by around 20,000 units.

But the tax concessions to investors are the big issue, a wasteful direction of funds and amounting to a subsidy of billions of dollars to already well off Australians at a cost to the rest. Also of course driving up housing prices for the poorest, those without a home. See the Henry Report for the costs of this tax regime and the stark statement that on average those who own/buy homes end up 12 times wealthier than those who do not.

Economics wise it is obvious what to do: politically it is unlikely to happen. 1.7 million Aust households own housing investment properties and they and the industry are vociferous in defending and promoting themselves. Just see how housing was avoided as an issue by both parties in the election and how quickly the lobby groups started screaming when the subject of restricting immigration was raised. Though of course this was just rhetoric anyway. Seventy percent of households are owning or buying a house, though the ratio of those buying is going up. Their interest in housing affordability is now at best neutral, if anything it is fixated on having their house increase in value. They will continue to be interest rate sensitive but that is all.

BTW I like your point about budget surpluses not actually being coins in a jar put away for a rainy day. The reduction of public economic discourse to a level which is below that of running a milk bar has been one of the major changes of the last ten years. And it was driven by the so called party of economic responsibility that prefered soundbites and propaganda to discussion. Keating drove an obsession with economics and finance markets into the centre of political discourse, Howard and Costello, and now Abbot, took this fetish and then stripped it of its content to create scary slogans about debt. And such is the paucity of economic knowledge in the media and by the public they seem to get away with it. Journalists meet their outrageous statements with grave faces and silence rather than the laughter that such statements made with a straight face should elicit.

I may be naive about political reality. I find it a shame and indictment on the political system when the right thing does not get done. When the leaders are fully aware of the solution and choose not to implement it. Instead they choose to extend their short term mandate. Clinging onto power.

My old Grandads wisdom again. “Anyone wanting to be a politician should automatically be disbarred from the job”

The ridiculously short term of office in Australia does not help the situation. At least they could spend 3 years to try and explain the concept. If effective in educating the population, maybe they could get a concensus to implement in the following term.

Bill, do you really believe in the housing shortage argument? Could it not be that we are simply in the middle of a speculative bubble? I agree with you prescriptions for removing the relaxations on capital gains for housing, and the negative gearing rules, but these alone should greatly reduce prices – and probably cause massive economic disruption.

Rents are pretty flat, so I really don’t buy the housing shortage argument.

Ralph Musgrave: You say quite rightly that if saving increased, that would cause unemployment. I’m not advocating allowing saving to increase, I’m saying the global level of savings needs to be kept constant by using taxation (such as inheritance tax or wealth tax). You say that it does not matter if average savings are $500 per household or $5000 per household. The fact is though that savings are not evenly distributed like that. Instead a they collect so that a few people become billionairs. Don’t you agree that beneficial (for the real economy) capitalism requires capital to have scarcity value and that that is lost when the economy is flooded with an ever increasing stock of capital. If the government has a policy of increasing the stock of capital year on year then that amounts to providing a ponzi scheme with asset prices.

G’day Bill,

The problem about winding back negative gearing is that the inevitable outcome will be increased rents. Those with highly geared properties purchased in the last couple of years are running at fairly significant losses. For example, we pay $420 p/w but if negative gearing is removed we’d be looking at around $650 just for the landlord to cover the mortgage let alone other property costs. The market distortion will be enormous; those with older properties can afford to have lower cost recovery yet those with newer have a high cost recovery. This will create a disincentive to invest in new property.

Can’t remember where I saw the stat, but approx. 80% of all investment properties are owned by the middle class, not the ‘rich’ as often thought. The rich people I know won’t touch rental properties. The mass transfer of wealth has been at the expense of the middle class, rather than the rich who have been the kind recipients, through the mass accumulation of debt to the middle class.

Don’t expect of political “leaders”, both federally and locally, to take any leads in resolving the issue. State governments now reply on property taxes to support their budgets and the Feds will not change the status – just look at the initiatives announced during the election, hang on, there were none. We’ve dug a f**king deep hole for ourselves that we can’t get out of without a massive dose of pain.

Johnno,

Renters can only pay so much out of their budget. If everyone put the rent up at the same time, it would be impossible to find renters for higher end homes. Rents would eventually find equilibrium, with landlords taking bigger losses. Most proposals call for removal of NG on the secondary market but to retain NG for new housing. The incentive to build new rental housing would still be there.

The problem is speculators in the secondary market would sell on mass, crashing the housing market. There might also be a short term housing crisis, with a lot of homes for sale temporarily out of the rental market. That’s why the NG subject can’t get airtime in the corridors of power.

Hi Stone,

Firstly I think you might be mistakenly taking Bill’s suggestion that a desire to net save is what is needed to be removed in order for full employment to be achieved and for poverty to end. My understanding of what Bill is trying to highlight is that given that the private sector on aggregate has higher savings than it invests (S>I) also known as a desire to net save, that the Government should play a role in providing employment opportunities by increasing its spending (on Infrastructure projects, community development housing, disability support etc etc) and maintaining (or reducing or increasing minorly) its taxation rate (G>T).

Secondly when you use the term capital, do you mean financial capital (money) or do you mean capital in its true economic sense as productive machinery and infrastructure.

I’ll assume you mean financial capital because you refer to it-

“If the government has a policy of increasing the stock of capital year on year then that amounts to providing a ponzi scheme with asset prices.”

I’m not 100% sure what you mean by the above statement but i’ll hazard a guess that you mean that if the Government increases its spending year on year that eventually this will result in asset price inflation or consumer price inflation. If you could clarify what you mean by ponzi scheme that would be great.

To this I would merely say that no one is suggesting that you run year on year budget deficits no matter what economic indicators are saying. Once sufficient Govt spending enables the achievement of full employment then know one is suggesting going beyond that, furthermore if the private sector desire to net save reduces then further changes in Govt spending may need to occur in accordance with those changes.

Hope that clarifies a few things for you

Nick

Nick, you are right, I meant financial capital- thanks for the clarification as to what to call things. What I meant about the ponzi scheme was that as far as I can make out, Bill recommends government spending of a level to produce full employment BUT ALSO taxation levels much less than the spending levels with the difference being accounted for as savings of the non-government sector. As the amount of money in savings increases year on year, there is more and more money available to push up asset prices (even if households keep money in the bank, doing so enables banks to offer cheaper loans to leveraged investors). This benefits those that were holding the most assets at the start of the process and is a Ponzi structure. Each nation competes with the other nations to attract investment money by favoring such ponzi growth. The countries that have the most ponzi friendly economy attract the most investment leading to inequality between countries. On a global scale that leads to a transfer of resources from the poorest of the poor to the richest of the rich. There is free flow of money from country to country so say the Japanese or USA government can think that it is fine to pump out more money but then carry trades create an asset price bubble somewhere else. The financial elites are able to play one country off against another so as to gain control of increasing levels of financial power. A non-expanding currency system together with redistribution by a wealth tax system would reverse that process.

Not sure I understand this entirely:

“The budget surplus may be applied to running down debt (that is, forcing the private sector to liquidate its wealth to get cash) but this strategy is finite. The alternative is to destroy liquidity (debiting reserve accounts) which is deflationary… the pursuit of public surpluses necessitates an increase in the net flow of credit to the private sector and increasing private debt to income ratios.”

– by running down debt do you mean private sector holdings of government debt?

– I don’t see how debiting reserves is deflationary in a particular way, compared say to letting bonds mature without replacement issues

– by pursuit of public surpluses, do you mean cumulative surpluses? I don’t see why running down an existing private sector NFA position with incremental surpluses necessarily requires increasing private debt. E.g. the existing US private sector NFA position is about $ 6 trillion. Why couldn’t that be run down (in theory) simply by the government paying off bond maturities with surpluses, without private sector borrowing?

(These are all theoretical points, I suppose, separate from the present fiscal situation)

Andrew – Speaking of housing issues, the SMH reports that Fitch will undertake a “stress test” on Australia’s largest banks that promptly sent the market into a retreat. Firstly I thought that the market knows more than it’s letting on but then realised it was Fitch – one of the rating agencies behind all of those wonderfully AAA rated securities. I think we know the outcome; a few criticisms but overall ok – let the bubble continue. None the less, we’re in a hole that just keeps getting deeper and no one has a clue what to do.

Hi Stone,

I understand and agree with what your saying in terms of the benefits of a wealth tax system.

Interestingly everything your describing in terms of a asset price inflation occurred in Australia during a period in which the federal government ran 11 or 12 consecutive budget surpluses not budget deficits. This would lead to question on the surface the logic of your argument that budget deficits would cause asset price inflation. This doesn’t imply that it couldn’t happen but you would have to agree that it does cast doubt over a the link between government budget deficits (G>T) and asset price inflation that would need to be resolved through further investigation.

Your description of a Government run ponzi scheme seems to resemble a description of the events that lead to the Global Financial Crisis is that a fair assessment of what your describing when you say-

“As the amount of money in savings increases year on year, there is more and more money available to push up asset prices (even if households keep money in the bank, doing so enables banks to offer cheaper loans to leveraged investors). This benefits those that were holding the most assets at the start of the process and is a Ponzi structure. Each nation competes with the other nations to attract investment money by favoring such ponzi growth. The countries that have the most ponzi friendly economy attract the most investment leading to inequality between countries. On a global scale that leads to a transfer of resources from the poorest of the poor to the richest of the rich. There is free flow of money from country to country so say the Japanese or USA government can think that it is fine to pump out more money but then carry trades create an asset price bubble somewhere else. The financial elites are able to play one country off against another so as to gain control of increasing levels of financial power.”

The only part that doesn’t fit in my assessment is the initial sentence regarding savings levels causing asset price inflation, the rest is a description of what occurs when you get a global speculative asset bubble which the GFC was in part. The reasons that savings doesn’t fit is because most industrialised nations from my understanding had really poor saving rates leading up to the GFC which would yet again cast doubts on the assertion that increased saving levels results in asset price inflation.

My personal belief is that what causes asset price inflations is not found in economic indicators like savings rates and budget deficits/surpluses but is a social phenomenon known as speculative behavior. Speculative behavior has history of arising out of range of circumstances that can be traced back to as early as tulip mania that occurred in Holland during the 17th century when the dutch community became obsessed with the beauty of the tulip, and this lead to the price of tulip bulbs increasing astronomically, this result in speculative behavior as more and more people bought and sold an increasing amounts of tulip bulbs making a tidy profit on each sale, this caused people to begin to borrow money to buy tulip bulbs under the expectation that prices would continue to grow. At the height of this tulip speculative asset bubble in todays terms tulip bulbs were sold for nearly $50000. This had nothing to do with savings or budget deficits but clearly was a social phenomenon that arose. If you want to read a good book pick up “A short history of financial euphoria” by John K Galbraith it is really insightful and was written well before the GFC and yet predicts an event similar will occur.

Regards

Nick

Nick, I agree that speculative bubbles happen in a fixed currency system (as in the tulip case) but in that case when they crash the inflation is extinguished by asset price deflation. In the post 1970s period asset prices have been able to ratchet up in fits and starts year after year, decade after decade. That never could happen in a fixed currency system. In a fixed currency system an asset bubble would cause asset price inflation, then the crash would cause asset deflation and so after a hundred years asset prices would be the same by and large as they were at the start. My understanding was that the Australian case of asset price inflation during surplus years was due to inflow of money from the rest of the world. I thought that the Japanese bubble in the 1980s was also caused by inflows of money from the rest of the world into Japan and coincided with Japanese surpluses. In fact in the midst of a full on asset price bubble there is typically so much money flowing into the nation hosting the bubble that that is the time when it is most likely to have a government budget surplus.

“The alternative is to destroy liquidity (debiting reserve accounts) which is deflationary… the pursuit of public surpluses necessitates an increase in the net flow of credit to the private sector and increasing private debt to income ratios.”

Like anon, I’m a little confused about this. How can reducing reserve balances be deflationary if increasing reserve balances is not inflationary? This seems contradictory from my naive position. I’m also unsure of the causal connection between the pursuit of public surpluses and increased leveraging of the private sector; I can see that the latter could follow from the former, but I don’t see why it necessarily has to.

Stone,

Yeah that’s really interesting would you recommend a book or a string of journal articles that I could read on the analysis of Japan’s bubble or Australia bubble, I’m all ears to reading about these types of crisis and how they emerged.

I have question though what comes first the money flowing in that stimulates the speculative behavior or does the speculative behavior cause the money to flow in.

Nick, I must admit that my sources are not very scholarly 🙂 eg http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_asset_price_bubble. But if you google everything seems to be in agreement. That wikipedia article makes out that with all that money to hand, a speculative bubble was inevitable. To my mind a speculative bubble needs both a glut of money and people willing to speculate. Also I get the impression that most bubbles don’t start as bubbles. Initially genuine real growth (due to efficient innovative production) attracts investors wanting a piece of the action. The inflow of money then tips things over to pure momentum trading speculation. Japan since the 1991 crash is a classic example of somewhere where there is a glut of money but asset price deflation because the Japanese have been frightened off speculating – but as that article mentions, the Yen carry trade allowed the Japanese glut of money to then fuel other subsequent bubbles in other countries where the speculators were not Japanese.

Stone,

Wikipedia ain’t a good source to base your economic arguments on seriously. It can be written by anybody and will generally reflect opinion that has not be reviewed by academics and professionals in the field. Wiki can be a good starting point for research into topics but in social science fields like economics which are highly debatable the opinion expressed in wiki needs to be read with the understanding that wiki will generally reflect only one of the numerous economics schools of thought for that topic. Also it will generally give a very simplistic view on a topic so that everyone can get the general simple idea of that topic. The reality is the economic world is far more complex then a simplistic mathematical functional relationship that wiki is describing in this insistence (i.e. speculative bubble = glut of money + speculative people).

I recommend that if your interested in economics look beyond wiki, as I said its a good starting point but you shouldn’t be basing your entire economic arguments on a source that is prone to bias and simplicity. You are only short changing your own understanding of a complex world by allowing your own opinion to be captured by such simplistic explanations of what is a complex economic world.

Nick, I totally agree that wikipeadia should only be a springboard for starting off from. To be fair to wikipeadia, the speculative bubble = glut of money + speculative people simplistic idea was my own bullshit not what wikipeadia said. The quote from wikipedia was “With so much money readily available for investment, speculation was inevitable, particularly in the Tokyo Stock Exchange and the real estate market.” If you come accross something that disagrees with the factual points (rather than the interprative bit) of that particular wikipeadia artical I’d love to hear about it. That artical does have references that can be followed up. To give wikipeadia some credit, they do have a very diverse set of economics entries from a very wide range of viewpoints. I totally agree that it is vital to base any understanding on raw data rather than other people’s interpretations. For me economics is a bit of a furtive side interest but I do try and avoid being biased in reading stuff just from one school of thought or from one type of author.

Stone,

I’m not denying that wiki isn’t a good starting point for research and I use it regularly for that purpose that’s what I’ll give wiki credit for.

I disagree with the statement that with so much money available speculative bubble was inevitable, because I think other aspects would also have to be present for speculation to lead to a crash, if we use just one aspect that springs to mind- the level financial regulation within an economy would clearly have an impact upon the ability of firms to speculate and even with excess funds within an economy if financial regulation and legislation restricts this type of behavior (i.e. Glass-Steagall Act 1932 in the USA) speculative financial crashes are less likely to occur. That is just one very simple example and by no means is a definitive statement like you would find on wiki that would say “if you have financial regulation you will not get speculative financial crashes.” The reality is that even with financial regulation you can get speculative financial crashes.

Nothing is inevitable history is contingent upon an infinite range of variables.

Nick, to my mind if there is £100B in savings, then realistic mundane regulation will be able to keep financial services working for the good of the real economy. If there is £100T in savings then there is absolutely no hope of having a regulatory framework capable of holding back the tide of speculative madness. Specifically about Glass-Steagall -my understanding was that Glass-Steagall prevented investment banks from being linked to regular deposit banks. Glass-Steagall would have done nothing to prevent Lehmanns Brothers (a pure investment bank). It would basically have still let the bubble form and burst. As far as I can see, Royal Bank of Scotland was one example of a deposit bank that made catastrophic losses from investment banking and was bailed out BUT- HBOS, Anglo Irish and Northern Rock made catastrophic losses from real estate lending that would not have been prevented by Glass-Steagall. The TBTF concept is supposed to be prevented by Glass-Steagall because pure investment banks like Lehmanns can be left to die but mixed banks like RBS or Barclays supposidly can not. To my mind, the goverment could have let RBS die but 100% guarenteed the deposits (ie wiped out the share holders and bond holders and left most of the employees looking for new jobs- just keeping a skeleton staff on to oversee the winding down process). The TBTF concept seems to me a political state of mind and Glass-Steagall is powerless to protect against it.

Stone,

Yet again I ask can you produce a book or a string of journal articles to back up your claims or analysis. I’m interested in your analysis but I don’t want a repeat of what you admitted a couple of blogs before “the speculative bubble = glut of money + speculative people simplistic idea was my own bullshit not what wikipeadia said.”

The Glass Steagall Act prevented the merging of the two institutions commercial banks with Investment banks we agree on that. If you are interested in the role of the merging of these two institutions played in the GFC I recommend you read Hyman Minsky’s “Stabilizing the unstable economy”, John K Galbraith’s “1929”, Alan Greenspan’s “The Age of Turbulence” and have a watch of the following youtube clip- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VlvVumYdMGs&feature=related. These will provide you with insight into how the merging of these two institutions through financial deregulation over the past 30 years played a massive role in the GFC.

To state that the real estate losses ie the ability of Collateral Debt Options to be passed and approved between a merged super institution (rather than two separated institutions) under the supervision of their own self regulation (rather than financial regulation provided by the Federal Reserve), had nothing to do with the removal of the Glass Steagall Act and similar legislation around the globe is absolutely hilarious and really embarrassing for you. Fact if Lehmann Brothers had only engaged in the standard investment bank operations that they had performed before the removal of the Glass Steagall Act for over 100 years they would still be in operation today. Even in the year of their collapse that part of their business was highly profitable. It was Lehmann Brother engagement in the new practices of real estate speculation that was their undoing which was only made possible through financial deregulation. Seriously go and do some reading.

You need to understand this- your not a professor, your not a professional in the field, your opinion while interesting and comedic is wish washy at best. The reason it is wish washy is because you have not spent the countless hours reading, analysing and writing a thesis, or masters or PHD. Those people who have done these things are the people who should be listened to by people like me and you, because their opinion is valued (and debatable) and has been subject to academic rigor and criticism.

I’m not saying you can’t have an opinion I’m just saying when you give an opinion it should be backed by your reading of experts in the field. I’m trying to be pleasant and understanding of your enthusiasm for economics and your desire to improve your understanding of the field but please take my advice even though it might seem harsh at first, it will help your understanding economics if you give a little a respect to the professionals in the field by reading extensively before forming an opinion.