I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When governments are financially constrained

I don’t run a blog on demand service. But today a specific request – almost a desperate plea – from one commentator to provide some analysis of a specific article coincided with many requests I have had for clarification about when a government is revenue constrained. The specific article in question apart from being one of the worst examples of uniformed economics journalism covers the ground about levels of government perfectly. So I decided to behave like a blog on demand service today despite wanting to write about how the US is a failed state. That will wait until Monday though and by then even more Americans will have slipped into poverty driven there by failed US government policy and a sclerotic system of government dominated by two main parties that are now incapable of governing in the public interest.

As an aside, I laughed this morning when my mate Marshall Auerback e-mailed me with the quip that Christine O’Donnell was a perfect candidate to advance the case for extreme fiscal austerity because she appears to be against stimulus of any kind. That was an amusing start. But apparently “she is very good looking” and given the quality of the US system of elections that she will apparently “get many votes through that alone” (Source). I have no opinion about either point! But how the hell does someone like that get anywhere near the halls of power? Answer: the failed state conjecture!

The specific article I was asked to discuss was published by our national daily (the only national newspaper) The Australia which is the centrepiece of News Limited (a la Fox) attack on sensible debate in this country. It is a bit more literate than the US Fox channel and its right-wing vehemence and outright biases are slightly more muted. But it is Rupert’s baby nonetheless.

The article (published September 17, 2010) carried the headline – States’ debt binge to top $240 billion as private sector faces squeeze.

While the article is focused on the behaviour of the Australian state governments the analysis I provide here is relevant to any federal system.

Australia’s system of government comprises a hierarchy with federal, state and local levels. The federal government which is fully sovereign in the sense that it issues its own currency and floats it on international markets.

The Australian government is never revenue constrained as a result of it being the monopoly issuer of the currency (the $AUD). Its status is equivalent to that of the national governments in the US, Japan, the UK, etc. The national governments in the Eurozone do not share this status and are not sovereign in the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) usage of this term.

Below our national government are state governments (6 states and 2 territories). These governments have specific spending and revenue-raising responsibilities and powers as specified in the constitution. We do not have the ridiculous balanced budget rule that the US system enforces on their state governments. State governments are free to run deficits if necessary and can raise debt if desired. They have no income taxing powers and raise most of their cash from land taxes (stamp duties) and receive significant redistributions of federal revenue via an revenue-sharing arrangement.

Local governments are in charge on urban amenities and levy rates on land values which provides most of their revenue.

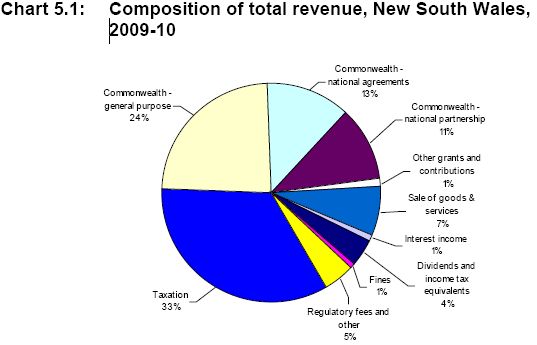

To give you an idea, the following graph is taken from the 2010-11 Budget Papers for the New South Wales government (the state I live in) and shows where the State government gets its revenue from. The domination of Commonwealth (that is, federal) redistributions is typical across the nation although different states exhibit variations on their own revenue sources. Some have less taxation capacity (because of land value variations) and impose more fines.

But the general point is that there is significant vertical fiscal imbalance in the Australian government system with the federal government having the lion’s share of the revenue sources, yet the states having significant spending responsibilities under the Constitution. This largely arose from the federal government assuming the states rights to raise income tax (in 1942) and the High Court banning the states from raising excises which are only federal powers.

Anyway, this blog isn’t about the relatively mundane structure of government in Australia or their fiscal relationships. My own view is that state governments should be eliminated (they are mostly corrupt bodies in the hands of land developers) and local government cleaned up (to eliminate the influence of land developers) making us a two-layer system of government. Then the national government could fund the Job Guarantee and the local governments would implement it along the lines laid out in this report – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy

But back to the article in question.

You immediately get the bias that is embedded in the article by the inflammatory headline – binge. That is what drunks do.

The article says that:

BORROWING by state governments is forecast to hit more than $243 billion, reducing available credit for the private sector as the economy recovers.

This is putting new pressure on Julia Gillard to rein in the federal budget and reduce debt … the borrowing is forecast to soar 52 per cent from $159.6bn this year to $243.2bn in 2014 to help fund upgrades to rundown transport, electricity and water infrastructure.

First, when you scale this against the State Product the proportion of borrowing over proposed by state governments over the next several years is minimal.

Second, the statement that state government borrowing is “reducing available credit for the private sector” is patently false. Yes, the state governments are revenue-constrained like a household. It is at this level of government that the analogy between the government and the household budget has resonance.

This means that the state governments have to finance their spending either via taxes and charges, borrowing, or asset sales. Over the neo-liberal period, the states adopted the view that borrowing was evil and so privatised significant assets (at bargain basement prices after paying huge fees to investment banks to facilitate the sales). It was a total disaster. Many of the assets have had to be re-purchased by government because the private operator went broke and the essential services would have been lost.

As an aside here is some personal experience.

Over the growth period leading up to the recent recession, the NSW government squandered a huge boost in stamp duty revenue that came there way as a result of the Sydney property boom and oversaw the largest degradation in public infrastructure in our history. The state government pursued surpluses over the entire boom period instead of maintaining the essential state infrastructure. It hired a massive squad of private consultants to help it cut spending. It entered into various public-private-partnerships which devolved its responsibilities for public infrastructure provision and handed them over to private equity interests who evaluated their investment decisions based on private profit rather than public good.

The capacity of public hospitals was devastated; railway bridges became dangerous. By the time the credit boom that had driven the NSW property boom was over and the commodity price boom saw the mining states (WA and Queensland) start booming, the NSW economy – the largest in Australia – was dead. All under the watch of NSW Treasury and its culpable Executive Directors. I could go on about the handling of the NSW economy by the state government at length. I no longer use the word government and NSW in the same sentence!

In the 1990s the NSW government, in pursuit of surpluses, began a privatisation binge. It started flogging off valuable state assets at massive discounts (to ensure the sales succeeded and hence avoid the political embarrassment) where the consultants who brokered the deals made millions and the state of public service fell.

I was involved in one of those sales – the privatisation of the Port Macquarie Base Hospital, which is located in a medium-size regional centre on the East coast about 310 kms north of Sydney.

I was asked by the Port Macquarie community group who opposed the privatisation to help them prepare an economic defence against the arguments developed by the NSW Treasury. The government was running a very high profile public campaign to make its ridiculous decision to privatise the main public hospital in the region look like a good decision. They kept quoting from a Treasury report about how good a decision they had made.

However, the government refused to make the modelling report public and just hectored the opponents who wanted to see the evidence. They kept referring to the report but no-one could evaluate whether the case being made was defensible or not.

The matter went the Land and Environment Court which handles disputes about planning and land use. As part of preparing the economic case for the community group who had mounted the court challenge, I received a leaked copy of that main Treasury evaluation report (I have friends everywhere!).

It was a disgrace and the modelling was seriously flawed. My evidence to the Court would have been devastating for the Government’s case. But I never got to provide the evidence as it was declared “inadmissible”.

This decision by the Court arose after several hours of legal debate which arose because the NSW government and its developer mates (who wanted to get their hands on the public assets) opposed the community group’s use of my evidence. The argument was that because the Report was leaked, any information in that Report could not then be used to develop alternative economic modelling which would be against the privatisation.

There was no claim that my evaluation was wrong – just that nobody could hear it because the Report was leaked. The legal babble was pretty amazing and after two days the judge declared my report “inadmissible”. The Government etc, in other words, had silenced me using legal technicalities rather than economic arguments, which was where the debate should have been focused.

The community group’s challenge was subsequently defeated and the Government privatised the hospital (it was the the first hospital privatisation in Australia). It was a total disaster.

The service contract gave the monopoly private operator much higher per head care payments that were offered anywhere else in Australia. As time passed, the standard of care fell and the public costs of providing health care in the region rose. The company fighting to make higher profits cut nursing staff further. According to NSW Health Department performance metrics, under privatisation, the hospital developed one of the longest waiting lists and one of the poorest performance records of all NSW hospitals. The private operator also found it hard to make profits.

Eventually, the NSW government was forced to buy-back the privatised Port Macquarie Hospital. All of what happened was foreshadowed in the modelling I provided in my suppressed Report. It was clear before the privatisation that it would fail because the economic cost-benefit analysis conducted by the NSW Treasury was seriously flawed. When I presented a more reasonable discounted cash flow analysis the privatisation was always doomed to fail (quite independent of your emotional position about public-private ownership). You can read about the failed privatisation here.

These privatisations and outsourcings and whatever else they have been called are one of the dirty jokes that the neo-liberal era visited on all of us in the name of economic efficiency and responsible government. I use the word “joke” because the beneficiaries of all this public largesse must have been laughing all the way to the bank as the stupid public officials (governments etc) fell prey to their lobbying and joyfully handed over the keys to the public purse. Overall, these events were an integral aspect of the way governments abrogated their true responsibilities to pursue and safeguard public purpose. Governments should never have become agents of private profit. The fact they have become such agents goes a long way to explaining why this huge global economic and social crisis is now upon us.

The other strategy that these neo-liberal obsessed state governments adopted was to pretend they had no funds for infrastructure development and so needed to form so-called public-private partnerships.

With PPPs, public purpose disappears and governments become underwriters of private profit. In NSW trade union superannuation funds have become compromised by the participation in PPPs and the conflict of interest that it presents the union movement. In PPPs, the risk is never transferred to the private sector. The only things transferred are public oversight in the infrastructure planning process and the delivery of public services; huge volumes of public funds; and, ultimately, the overriding public purpose of interest becomes usurped by the unquenchable pursuit of private profit. Not a good look at all.

Please read my blog – Landlocked … but still swamped by budget hysteria – for more discussion on this point.

I should also note that the household-government budget analogy never has resonance at the federal level if the national government is sovereign.

Anyway, back to the article. My meandering reflects that it is late Friday afternoon and it has been a long week already!

The fact is that the issuing of debt by the state government is an essential way it can raise funds to finance large and expensive public infrastructure developments which underpin economic growth in the state economies.

The reluctance to borrow over the last decade or more by state treasurers to has been a myopic strategy. The governments were drowning in property tax revenue and decided to wipe out their outstanding debt because the deficit terrorists had convinced them that the debt was evil and compromising the capacity of the state to grow.

Nothing could have been further from the truth. The Government’s reluctance to use their burgeoning coffers to fund infrastructure growth has reduced the potential growth path of the states and the debt retirement and interest savings have destroyed the wealth holdings and incomes of private savers.

The run-down of existing infrastructure is now revealing itself to be a myopic strategy – one that will cost more in the long-run than if there had been steady capital spending growth over the life of the Government.

State governments are now realising that their past penury is catching up with them. At last they are realising that debt can be good a good thing – spreading the burden of public investment over the generations that will benefit from it.

Education is a good example. Investment in public education underpins child and community development but as the state governments built their surpluses in recent years they allowed teachers’ pay and conditions to lag behind other occupations.

The Government is starting to realise that a responsible fiscal position for a state government is that they should borrow to build public infrastructure. These assets spread benefits into the future and borrowing allows future generations to pay a share of the costs in some proportion to the benefits they receive.

The Government’s previous exhortations that debt was irresponsible have been abandoned and they will now borrow to provide $3.5 billion for increased spending on roads, rail, hospitals and education.

So the renewed commitment to borrowing is a signal that the state governments are behaving the way they should act. The lack of attention paid to essential infrastructure including public hospitals, public schools; public transport; mental health and disability services; water and the environment has created a state of crisis.

Why have they waited so long to realise that state budget deficits funded by debt provides public infrastructure and services which generate enduring benefits beyond immediate users? This enhances productivity and economic growth and creates new employment and apprenticeships.

Government inaction has seen the mentally ill receiving treatment in prison because of a lack of crisis and community care. It has forced young people with brain injuries to live in Commonwealth nursing homes because of a lack of supported state accommodation. The public transport systems are in chaos. Our public schools fail to provide safe and stimulating learning environments for our kids.

Does the private sector get squeezed by state borrowing?

Short answer: No!

The Australian article claims that:

The burgeoning public debt levels have sparked warnings about higher interest rates as the private sector competes for funding as the economy gathers pace.

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry director of economics and industry policy Greg Evans pointed to International Monetary Fund research that found rising public debt levels could lead to interest rate rises.

The financial crowding out hypothesis is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw’s awful macroeconomics textbook, which poisons thousands of young minds daily and is representative of the overall approach taken by my (disgraceful) profession, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory.

Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

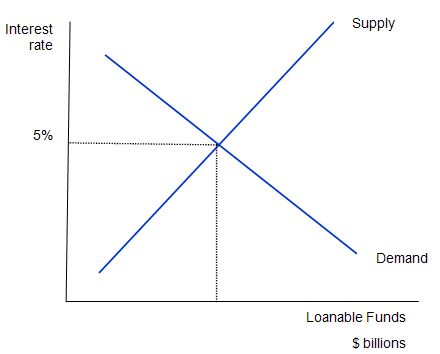

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment.

Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that budget surpluses are akin to this. They are not even remotely like private saving. They actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of budget surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to “any other market in the economy” despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates – read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consquences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a budget deficit. Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

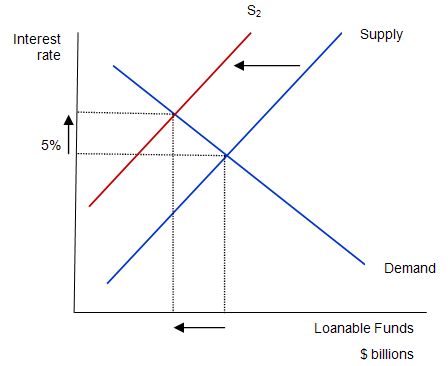

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2. Why does that happen? The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising budget deficit reduces public saving and available national saving. The budget deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Sometimes, this makes is hard to know where to start in debunking it. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But national and state governments do borrow. The former for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations and the latter because they are financially constrained.

So doesn’t this borrowing increase the “public” claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no!

MMT does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates. MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors.

Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading “financial crowding out”.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

From a macroeconomic flow of funds perspective, the funds (net financial assets in the form of reserves) that are the source of the capacity to purchase the public debt in the first place come from net government spending. Its what astute financial market players call “a wash”. So at the federal level, the funds used to buy the government bonds come from the government!

The funds to buy government bonds come from government spending! There is just an exchange of bank reserves for bonds – no net change in financial assets involved.

What about the impact of state government borrowing on financial markets?

The significant point to understand that there is no finite pool of saving that is competed for by any level of government. At the level of commercial banks, loans create deposits so any credit-worthy customer can typically get funds. Reserves to support these loans are added later – that is, loans are never constrained in an aggregate sense by a “lack of reserves”.

So credit-worthy private borrowers are not constrained by the state borrowing.

Further, total saving grows with income. Importantly, deficit spending by both federal and state governments generates income growth which generates higher saving. It is this way that MMT shows that deficit spending supports or “finances” private saving not the other way around.

If the state governments are using the borrowed funds to develop productive public infrastructure that also leveraged by the private sector to expand their profit-making opportunities then the future growth path will likely be higher. This will not only stimulate growth in saving but also expand the revenue-base that the state government may tap in future years.

However, other forms of crowding out are possible. In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

Further, while there is mounting hysteria about the problems the changing demographics will introduce to government budgets all the arguments presented are based upon spurious financial reasoning – that the government will not be able to afford to fund health programs (for example) and that taxes will have to rise to punitive levels to make provision possible but in doing so growth will be damaged.

However, MMT dismisses these “financial” arguments and instead emphasises the possibility of real problems – a lack of productivity growth; a lack of goods and services; environment impingements; etc.

Then the argument can be seen quite differently. The responses the mainstream are proposing (and introducing in some nations) which emphasise budget surpluses (as demonstrations of fiscal discipline) are shown by MMT to actually undermine the real capacity of the economy to address the actual future issues surrounding rising dependency ratios. So by cutting funding to education now or leaving people unemployed or underemployed now, governments reduce the future income generating potential and the likely provision of required goods and services in the future.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues. If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that. It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example). But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

The Australian article quotes the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry director of economics and industry policy who offers the following nonsense:

Business wants government to return the budget to balance and reduce public debt as a stronger budget position means greater flexibility to deal with future economic shocks but it is also important in reducing pressure on long-term rates … Higher than necessary long-term rates impact economic growth and the investment decisions made by business. In periods of economic expansion it makes it harder for smaller and more exposed borrowers as they effectively get crowded out of the market, making it more difficult to access funds at reasonable levels.

He would never pass a macroeconomics course at any university that I was teaching at!

This is a common myth though. A sovereign government (such as our federal government) has no more or less flexibility as a result of its past fiscal outcomes. Whether it was in deficit or surplus in the past means nothing in terms of its capacity to spend in the current period. Spending in the current period places no constraints on its capacity to spend next year or the year after.

It might be that by running appropriate budget deficits now it can net spend less next year as economic activity improves but that is not a financial constraint. It just says that budget deficits will have economic outcomes that may require varying fiscal positions in the future.

But why is this quotation being offered in the context of a rave about revenue-constrained state governments? The journalist clearly has got the levels of government confused and fails to understand that the analysis of the implications of spending and borrowing is quite different at each level. She is seemingly desperate to get as many myths into her article as possible and so just had to pump out the tirade from the business lobby which is not even pertinent for her article’s main message.

The previous analysis on crowding out should allow you to reject the nonsense the business representative is offering anyway, whatever level of government.

The rest of the article is a series of quotations from business economists – each one falling into the “crowding out-need for fiscal discipline” logic failure.

One quote comes from the Federal Opposition Treasury spokesperson which confirms why they would have been unfit to govern (they lost the recent federal election). Mr Hockey says the:

… massive surge in public sector borrowings is going to crowd out the credit markets at a time when we’ve got above-trend growth … There is only so much money available to Australia as a proportion of the global economy. If there is a gap between the demand for funds from Australia and our proportion of the size of the global economy, then it does have an influence on the availability of funds more generally to the Australian private sector.

That could be a question for students – as a demonstration of some of the worst pieces of economic reasoning you could ever find. Who is advising this man? Where was the advisor educated? For sure, it will be another university that goes on my black ban list for prospective students wanting to learn some real macroeconomics.

The ability of the banks to expand credit is not constrained in the way suggested. It is all about price not volume. Please refer back to my earlier discussion above about crowding out.

What are the implications of state government borrowing for federal spending capacity?

You will note that the article claimed that the increase in state borrowing (to fund infrastructure) is “putting new pressure on Julia Gillard to rein in the federal budget and reduce debt”. Julia Gillard is the Prime Minister for those who haven’t realised that we actually now have a federal government after the non-result at the August 21 election.

Does this statement have any credibility? Answer: None!

Why? For all the reasons noted above. The federal government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. It voluntarily chooses to borrow (erroneously thinking that it somehow indicates fiscal responsibility). But it really (conceptually) borrows back what it has spent. Its a wash.

It doesn’t compete with anyone for funds in this regard.

Conclusion

This article will qualify as a finalist for the worst article by an economics journalist for 2010 which I will announce in my annual awards on December 31.

It rehearses every myth and lie and misunderstanding that you can find. I take that back. It failed to squeeze in a discussion about the ageing population.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

Bill, I’m very scared about the level of complacency there seems to be about the glut of money building up at the wealthiest end of the economy as a result of budget deficits. You seem entirely blase about the fact that endlessly increasing savings/investments/asset prices leads to a ponzification of the global economy. To my mind you haven’t offered a credible justification for why MMTers are reluctant to match £ for £ the government spending with taxes on wealth. You point out the accounting reality that there would be no nominal growth in the global economy if all countries did that. But so what- what matters is not nominal growth but for the work that needs doing to get done and for people to be able to enjoy the real benefits. The current global glut of wealth (meaning value of investments/assets versus earnings) surely is a severe impediment to that goal being achieved. I agree that if one country manages to get a speculative bubble going then that can parasitically suck resources in from the rest of the world but that is hardly a basis for an enlightened economic system.

Just a small clarification that, in the US, there is no legal restraint — either from the Constitution itself or from the Federal Government — which requires state governments run a balanced budget. State governments have placed this constraint upon themselves through the adoption of balanced budget amendments to their respective constitutions. The worst element of these balanced budget amendments is that they also forbid surpluses, so state governments have absolutely no choice but to act in a pro-cyclical fashion.

At present, i think 48-49 out of the 50 states require a balanced budget.

“It might be that by running appropriate budget deficits now it can net spend less next year as economic activity improves but that is not a financial constraint. It just says that budget deficits will have economic outcomes that may require varying fiscal positions in the future.”

This seems to imply there is some legitimacy to financial planning for budget deficits, based on the expected rollout of real constraints in the future.

It also suggests that planning based on an erroneous interpretation of future financial constraints is not entirely unproductive, given the prospect of some degree of correlation (inadvertent) between strategies that correspond to either the correctly inspired planning process or the incorrectly inspired one.

I.e. the value of planning is somewhat invariant to whether the true constraint is real or financial.

State governments are nothing more than economic vandals.

Wow. A LOT of useful comments Bill. Yet there is always room for more.

1) Given the endless confusion about public debt, isn’t it even more helpful to stress to students and newcomers that sovereign nations do not “voluntarily choose to borrow”, rather, they voluntarily pretend to borrow

2) Since any sovereign can create it’s own currency at will, and can only constrain it’s spending as a voluntary political decision, doesn’t national financial constraint equate to constraining public initiative?

ps: DS, thanks for the info about US state budgetary laws; if you’re in the states, I’d like to discuss that further with you offline; please write to me at rge at operationsinstitute dot com; many thanks

Bill –

I think the NSW state government is the only one that’s actually corrupt. Unfortunately the other states often achieve similar results by sheer incompetence!

However I disagree with your solution of abolishing state governments for two reasons. Firstly there are some things that can be done more efficiently at state level than at local level. Secondly the federal government makes exactly the same mistakes, and I suspect local government does too.

I think the solution is total transparency. At the absolute minimum, all non disclosure agreements should have short (no more than a year) sunset clauses. Ideally everything relating to economic matters should be made public. Indeed there’s very little justification for keeping anything at all from the public – the only exception I can think of is where there are civil defence implications, and that’s more likely to be a federal matter.

I also take issue with your description of stamp duties as a land tax. They’re a land transfer tax, and there’s a big difference – land transfer taxes are an impediment to business. There are land taxes at state level as well, but they’ve generally got too many exceptions to be an adequate revenue source.

It’s depressing. Even a sympathetic compassionate guy and nobel laureate in economics like Joseph Stiglitz doesn’t get it. He writes about the need for another stimulus in Politico:

What is Stiglitz thinking? That the computers at the treasury and the FED have some memory limit and refuse to store numbers greater than 9,999,999,999,999? “System Error #179: Number out of range! Please shut down the system. Possible solution: Reduce the deficit.”

Off topic – news on banning fractional reserve banking. There was a lively debate on Billyblog in January on the latter subject. A bill was presented to the U.K. parliament yesterday which aims to ban fractional reserve banking. Plus there was an article with the same aim in the Wall Street Journal yesterday by a U.K. politician. URLs respectively are:

Billyblog: https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=7299

U.K. parliament: http://www.positivemoney.org.uk/2010/09/douglas-carswell-mp-introduces-bill-to-stop-fractional-reserve-banking/

WSJ: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703376504575491611740494630.html

Bill, I just want to get my head around the MMT idea that all “desire to save” should be accommodated by deficit spending. In the UK >4000 bankers get annual bonuses greater than £1M. That makes scant contribution to consumer price inflation because they already have more money than they could possibly spend. Under MMT would you actually decrease taxes for the immensely wealthy (as per G.W. Bush) as money going to them does not increase consumer price inflation? You say money only matters if it is being spent and so there is no possibility of “excess money”. Are you saying that there is no such thing as an overly wealthy oligarchy?

Bill:

This is a great post. One of the takeaways for me was that there are significant differences in how economic principles operate between the public and private sectors. The most obvious is borrowing. Then when you started discussing real constraints, I started thinking about how public infrastructure should be seen as a real resource and how I had always conceptualized it as capital investment. Thinking of public provision for infrastructure as “capital investment” creates other kinds of misunderstandings.

Clearly public infrastructure is available to all economic participants (households and firms), so it differs fairly obviously from private investment. The idea that public investment needs to “provide a return” doesn’t really make sense, because the private actors who use these resource generate a return, we are asking the public investment to provide double returns. It is another form of socializing losses and privatizing gains.

stone: I think you fail to see how direct government spending can reduce the “glut” by redistribution of net financial assets from the top back to the public. In fact, the lack of spending – running surpluses – increases income inequality and increases the reliance on private lending to generate economic activity, which requires increased indebtedness and therefore higher asset prices. The fact that current economic policies worldwide are not designed to help the public is not an indictment of MMT’s description of the financial system.

Don’t blame the hammer if someone hits you on the head with one.

Stephan: I don’t think Stiglitz is saying what you imply. The US debate over tax increases to the wealthy is an interesting one. While tax increases reduce aggregate demand at the macro level, once you start to apply that to social segments, different rules may apply. For example, if the wealthy tend to save their tax cuts vs. most households spending theirs, you would want a tax cut focused to most households.

The political reality in the US is that spending is being constrained by deficit fear mongering. Also, if the f*****g banks aren’t lending, I don’t expect the wealthy to start a spending spree. If the government can use those tax “funds” (from a political perspective) to increase spending, that would be preferable to allowing the wealthy to continue to bank theirs. Obviously increased deficit spending overall would be preferable. The fact that Stiglitz uses neo-liberal language to make a political point doesn’t mean he doesn’t get it.

September 17, 2010

This is the print preview: Back to normal view »

Ellen Brown

Author, Web of Debt

Posted: September 17, 2010 02:25 PM

Basel III — Tightening the Noose on Credit

The stock market shot up on September 13, after new banking regulations were announced called Basel III. Wall Street breathed a sigh of relief. The megabanks, propped up by generous taxpayer bailouts, would have no trouble meeting the new capital requirements, which were lower than expected and would not be fully implemented until 2019. Only the local commercial banks, the ones already struggling to meet capital requirements, would be seriously challenged by the new rules. Unfortunately, these are the banks that make most of the loans to local businesses, which do most of the hiring and producing in the real economy. The Basel III capital requirements were ostensibly designed to prevent a repeat of the 2008 banking collapse, but the new rules fail to address its real cause…

What precipitated the credit crisis and bank bailout of 2008 was not that the existing Basel II capital requirements were too low. It was that banks found a way around the rules by purchasing unregulated “insurance contracts” known as credit default swaps (CDS). The Basel II rules based capital requirements on how risky a bank’s loan book was, and banks could make their books look less risky by buying CDS. This “insurance,” however, proved to be a fraud when AIG, the major seller of CDS, went bankrupt on September 15, 2008. The bailout of the Wall Street banks caught in this derivative scheme followed.

The smaller local banks neither triggered the crisis nor got the bailout money. Yet it is they that will be affected by the new rules, and that effect could cripple local lending. Raising the capital requirements of the smaller banks seems so counterproductive that suspicious observers might wonder if something else is going on. Professor Carroll Quigley, an insider groomed by the international bankers, wrote in Tragedy and Hope in 1966 of the pivotal role played by the BIS in the grand scheme of his mentors:

[T]he powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent private meetings and conferences. The apex of the system was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the world’s central banks which were themselves private corporations.

The BIS has now become the apex of the system as Dr. Quigley foresaw, dictating rules that strengthen an international banking empire at the expense of smaller rivals and economies generally. The big global bankers are one step closer to global dominance, steered by the invisible hand of their captains at the BIS. In a game that has been played by bankers for centuries, tightening credit in the ebbs of the “business cycle” creates waves of bankruptcies and foreclosures, allowing property to be snatched up at fire sale prices by financiers who not only saw the wave coming but actually precipitated it.

Nill,

Great article on the politics and operational aspects of state budgets, deficits and borrowing, notably related to public infrastructure.

Thanks, as usual.

Given that monetary sovereignty accrues only to national governments – that of all the people – the lack of revenue-sharing of sorts leaves the states without the benefit they should have of providing for their priorities without paying excessive borrowing costs.

Again, these should be unnecessary as it is the same group of taxpayers and citizens that own the sovereign money system, organized and setting priorities on a different level.

These benefit transfers from the federal government to the states for public infrastructure are included in the reforms proposed by the American Monetary Institute (www.monetary.org) .

Under the AMI proposal, the self-restraint that requires the issuance of federal debt is lifted and the government is actually using its sovereign money-creation powers to fund our national economic objectives via the annual budgeting process. A portion of that funding is set aside annually to provide debt-free money to the states to obviate the need for state government borrowing and to protect those same sovereign citizens from the payment of unnecessary taxes at the state level.

Even state governments can benefit from our release of the legal constraint of forced borrowing by the government.

The more of billy blog I read the more it makes sense.

This is the true test. The more conventional economics I read the more I get confused.

The existing monetary system and associated economic theories are convoluted on purpose. To disguise the iniquity in the system.

I’m starting to see through the mainstream propaganda (especially articles from bank economists). Once I recognize the profit intent behind an article it gets easier to debunk.

Thanks Bill.

Aidan,

I never got around to thanking you for considered reply to my somewhat facetious post.

Your points on mining are spot on.

But I am curious.

Have you considered that what is impedes business might be how business determines productivity?

If asset inflation, in the form of the monetary value of land title, drive profits then of course land transfer taxes are an impediment.

It’s a construction of profit, value, and productivity that leaves title holders perpetually vulnerable to the vagaries of asset inflation, if land value is divorce from productive -real goods and service provision – value.

A brief conversation with any knowledgeable Indigenous person on thhowe subject of land value can dispel any illusions about axiomatic relationships between monetary value and land title value. Talk to any farmer on the productivity issue and it will give you nightmares.

Surely it is more of benefit to all concerned to work within an economic system that has the ability to co-ordinate these perspectives of land value rather than distorting markets by predominantly accounting profitability in ways that discount productivity and sustainability.

I am using sweeping generalisations here, and we do seem to have a regime of land of taxes that are crude, unfocused and, at times, ridiculous. The regulation of land, title and value needs to be managed with taxation that accounts for the fundamental reality that it ‘aint going nowhere’ and we are all destined to die.

What works with the land and how we work with it is what, ultimately, makes an economy that no business acumen can override.

What we consider to ‘good’ business, a ‘good investment’ or a ‘profit’ is meaningless without that perspective.

And, no, I don’t think that understanding can be forced. I think that accurate information will lead most people to draw a similar conclusion.

As for NSW being the only corrupt state hmmm. Come to Queensland.

Apologies for poor proof reading in my post

‘land value is divorce from productive’ should read ‘land value is divorced..’ and ‘Indigenous person on thhowe subject’ simply ‘Indigenous person on the subject’

stone:

I think I understand where you’re coming from – you worry about wealth distribution not just aggregate wealth. Fair enough – this is a problem.

The solution to rich people accumulating massive amounts of assets is not tight budgets, because that usually hurts the poor the most. If the expenditure is well targeted, ie at the lower income brackets, then it’s supporting their ability to save first and foremost, with a trickle up effect for the rich.

The main cause of inequality is uneven flows of income between the sectors – right now in the US income is being distributed upwards at crazy rates, and yes, they spend it on risky wall street assets that then inflate and pop. The best way to deal with this is simply a better structured tax system. Get rid of loopholes and up the rates on the higher brackets. After all, during the post war boom, inequality dropped, and the middle class grew and saved, all because of deficits and well designed tax systems.

MMT says you have to tax – not to get revenue, but to stabilize the currency, and promote the public good. Asset bubbles are in no one’s best interest.

(I cut and pasted this comment from the last blog because you might have stopped checking that one)

@ Andrew, “The existing monetary system and associated economic theories are convoluted on purpose. To disguise the iniquity in the system.”

“The demand for the new freedom was thus only another name for the old demand for an equal distribution of wealth.” – Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom.

Enjoying the blog Bill, Thanks.

Thanks Bill, illuminating as always.

You have to give it to the conservatives though. Hypocrisy is no barrier to them. They do prove, however, that you can fool most of the people most of the time. The article is breathtaking in scaremongering about debt in the context of highlighting the need to upgrade “rundown” infrastructure, without ever admitting the reason it came to be that way……the previous Federal government underfunded these programs since the mid-90s through insufficient State transfers in the interests of maintaining an inappropriate budget surplus (and scoring political points to be sure, given funding pressures in Labor states fitted their “debt is bad” narrative). The unfortunate consequence of this was that revenue-constriained State governments bought into this idea as well because public opinion had been hoodwinked too, but also because they were becoming politically unpopular. Resources such as water, health and education can become awfully run down over a 12yr period, as we’ve found out.

There is also a fair degree of chutzpah….we’ve just lived through the largest financal and economic crisis we’ve witnessed in our lifetimes (fingers crossed), thanks mainly to governments providing stimulus, however hamfisted it might have been. So the theory about crowding out and public debt had the perfect laboratory in which to assert itself. It wasn’t even a close thing though, was it, despite articles like this banging on senselessly about some link. Quite apart from the loanable funds theory you note, actual demand for private debt during that time was essentially donut. Investors and banks didn’t want a bar of it. This is typical of all recessionary periods I’ve lived through or watched from afar. Crowding out is something I’m sure these people yelp when the doctor taps their knee with a hammer/. And guess what, public debt is large, and demand for private debt is going nuts. How do rags like “The Australian” explain this. Answer? They simply don’t include it in articles.

Re Hockey’s comment……the fact that he doesn’t understand a fraction of what he talks about is scary. He should know that demand for Australian and State Government bonds is actually rising, and at a time when we have a budget deficit. Oh the horror of intellectual poverty.

Mark Lennox

It looks like a good read, might give it a go one day. I am familiar with George Orwells work. As an aside, George Orwell warned against Hayeks book. “return to ‘free’ competition means for the great mass of people a tyranny probably worse, because [it would be] more irresponsible, than that of the state.”

I was pondering. Animal Farm is entrenched in the modern western physche, such that there is an intense fear of a left wing highly centralised command economy.

As I have played Monopoly as a child I am very aware that “Free Markets” eventually get corrupted by monopoly powers. Monopoly being the inevitable result of the leverage of accumulated capital. There are also trade associations, loose cartels, oligopolies etc to worry about. “Free Markets” reward those that run fastest first and get ahead, thereafter it becomes increasingly easier to stay ahead. Over time, there is ever increasing reward for capital accumulation and diminishing reward for productive effort.

I wonder if Hayek or Orwell had written a book driving Free Market capitalsim to a logical end state. A single bond type supervillain controlling the population through warped 24 hour news, false flag wars, crippling debt repayments and corrupt crony politicians. If they had, Maybe there would be so much Hubris and Chutzpah knocking around the neo-liberal ranks.

Maybe there would NOT be so much Hubris and Chutzpah knocking around the neo-liberal ranks.

No edit feature here.

George Orwells new book. “The Free Farm”.

Read how the cunning Pigs take over the farm from a hapless Farmer. Pigs run the bank and Horse is made president. Laugh with us, as they introduce debt bearing vouchers to finance all farm activity. Squeal with delight as the sheep are forced to pay rent for their grazing rights.

The observer – I never laughed so much in all my life. Watching those dumb sheep competing for the best investment plots.

Andrew,

Haven’t you read 1984?

Grigory Graborenko: Thanks for your response telling me that “MMT says you have to tax – not to get revenue, but to stabilize the currency, and promote the public good. Asset bubbles are in no one’s best interest.” I think the dispute I have with MMT is that to me it is clear that those taxes are needed (for the reasons you describe) but what is more they need to be sufficient to prevent any “global economic growth”. To my mind “global economic growth” is just a euphemism for a global asset price ponzi scam that can only benefit those starting off with the most wealth. By definition sufficient taxation would be that which matched government spending £ for £. Tight budgets hurt the poor when they are designed to do so (as in the IMF austerity measures). How could you say that inheritance tax would hurt the poor? Or there could be a flat % tax on property. In order to legally have ownership of anything (cash, real estate, stocks whatever) you could have to demonstrate that you had paid tax on it. Such taxes would make sure wealth no longer accumulated at the top end of the economy. I’m utterly baffled at how MMTers wring their hands about wealth inequality and the power of the banks and then say that they do not believe in taxing away that wealth back to post WWII levels or even taxing it sufficiently to prevent the divergence of earnings and asset prices from widening further.

Neil,

Yes I did, a long time ago, and it’s stuck in my head. Great book.

I must proof read more. The first “Animal Farm” reference should have referred to 1984.

Cack.. that spoilt the point I was trying to make.

Andrew Wilkinson,

I’ve read 1984. Who was Orwell again? i remember reading an article that said he was an insider to the plans of the few or was that Aldous Huxley? On second thought it was Huxley but he was a friend of Orwell yes? Google.

Remember Fredreich Hayek was an acclaimed economist, not in the watered down sense of knowledge and accreditation we now see ala Barack Obamas Nobel Prize or the continual disregard for the business cycle by the Princeton educated economic rockstar Bernanke (http://ht.ly/2JAT5) but of advancing understanding.

Friedrich Hayek, wrote that many economists by mimicking the methodology of the physical sciences had an inferiority complex because the social sciences required a different methodology than the physical sciences.

For me, ying/yang or the star of david. There is ALWAYS another side of the argument, that’s what nature is all about… cycles.

Lennox, Hayek held doctorates in law and political science but not economics, and he is often considered to be chiefly a philosopher owing to his trans-disciplinary work that bridges philosophy, political science, and economics.

Wynne Godley did not hold a degree in economics either, so he was not technically an “economist” – something that apparently concerned him (needlessly).

@Tom

My new hobby. To defend my dead compatriots (Mises, Hayek, Schumpeter, Polanyi, …) against silly appropriation from US citizens 😉

@Andrew

You are mostly right about Hayek. What is important to note is, that there was not such a thing as economics in academia for guys like Mises and Hayek. Political economics was part of the curriculum of law or philosophy. Anyway you must always read Hayek in the proper historical setting. You might be astonished but Hayek would have been in favor of a public option in healthcare. He has written that even while fearing to walk down the road to serfdom. His contemporary US followers are illiterate and should be simply ignored. Hayek would for sure not join their ranks. Although I still think its makes more sense to read Polanyi then Hayek. Guess that is a polictical choice.

Stephan: To defend my dead compatriots (Mises, Hayek, Schumpeter, Polanyi, …) against silly appropriation from US citizens

I like Mises, Hayek, Schumpeter, and Polanyi, but they were creatures of their times and they need to be approached that way, just like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx, and Keynes. They all made important contributions, but when the are almost deified by their followers, what they had to say becomes a lot less helpful today and can become a hinderance if taken to an extreme, since none of them had all the answers.

What many people don’t realize is that Keynes read The Road to Serfdom and complimented Hayek on it. Hayek was right to be concerned about statism. I am too, which is why I call myself a libertarian of the left. The principal concern now is state capture by plutocratic oligarchs and the major problem is socialism for the rich.