I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Landlocked … but still swamped by budget hysteria

I am feeling a little uncomfortable at present – landlocked. I am working in Almaty, Kazakstan, which is part of Central Asia and one of only 44 countries that do not have a sea edge. But it would be worse if we were in Uzbekistan which is one of only two countries that is doubly-landlocked. That means it is a landlocked country surrounded by other landlocked countries so I would have to cross two national borders to get to the surf! I will report on what I am up to over here in more detail at a future date. But even though this is a remote region, the Australian national broadcaster the ABC has tracked me down. They rang early this morning and want to talk about the Australian Treasury’s claim that unemployment fears are easing and skills shortages are now the threat to our economy – what? 14 percent of our labour underutilised and we are now back to the skills shortage debate. Anyway, the ABC has been on my mind overnight …

I received an E-mail yesterday from Australia yesterday from “someone” who knows me very well – it said “… I heard an interview driving home from work today that would have caused you to drive the car into a brick wall. Robert Carling from the Centre for Independent Studies talking to Mark Colvin. Unbelievable.” Anyway, like a loser, I read the transcript of the interview after I had finished a torrid day here in Almaty discussing structural adjustment options for the CAREC economies. I was safely esconced in my hotel room – in control of nothing more dangerous than my little mp3 player (which didn’t get thrown at any brick wall after I read the transcript. I remained calm.

The interview was on the national radio current affairs ABC PM program. It demonstrates the sad shape of public commentary and the now confirmed right-wing bias of ABC current affairs broadcasting. It also sits with some of the nonsense that I read in the European press in the last few days about Latvia.

The opening gambit from the interviewer (Mark Colvin) was:

As the global financial crisis eases there are some voices warning that complacency could lead the world into another economic crash. One of them is the former New South Wales Treasury economist Robert Carling, now a senior fellow at the free-market Centre for Independent Studies. He’s been studying the latest figures from the United States Congressional Budget Office and the deficit figures he’s seen there have him worried.

Carling was Executive Director, Economic and Fiscal at the NSW Treasury from 1998 to 2006, the period over which the NSW government squandered a huge boost in stamp duty revenue that came there way as a result of the Sydney property boom. and oversaw the largest degradation in public infrastructure in our history. The state government pursued surpluses over the entire boom period instead of maintaining the essential state infrastructure. It hired a massive squad of private consultants to help it cut spending. It entered into various public-private-partnerships which devolved its responsibilities for public infrastructure provision and handed them over to private equity interests who evaluated their investment decisions based on private profit rather than public good.

The capacity of public hospitals was devastated; railway bridges became dangerous. By the time the credit boom that had driven the NSW property boom was over and the commodity price boom saw the mining states (WA and Queensland) start booming, the NSW economy – the largest in Australia – was dead. All under the watch of NSW Treasury and its culpable Executive Directors. I could go on about the handling of the NSW economy by the state government at length. I no longer use the word government and NSW in the same sentence!

As an aside, in the 1990s (before Carling arrived there but part of the same culture he now expresses) the NSW government, in pursuit of surpluses, began a privatisation binge. It started flogging off valuable state assets at massive discounts (to ensure the sales succeeded and hence avoid the political embarassment) where the consultants who brokered the deal made millions and the state of public service fell.

I was involved in one of those sales – the privatisation of the Port Macquarie Base Hospital, which is located in a medium-size regional centre on the East coast about 310 kms north of Sydney.

I was asked by the Port Macquarie community group who opposed the privatisation to help them prepare an economic defence against the arguments developed by the NSW Treasury. The government was running a very high profile public campaign to make its ridiculous decision to privatise the main public hospital in the region look like a good decision. They kept quoting from a Treasury report about how good a decision they had made.

However, the government refused to make the modelling report public and just hectored the opponents who wanted to see the evidence. They kept referring to the report but no-one could evaluate whether the case being made was defensible or not.

The matter went the Land and Environment Court which handles disputes about planning and land use. As part of preparing the economic case for the community group who had mounted the court challenge, I received a leaked copy of that main Treasury evaluation report (I have friends everywhere!).

It was a disgrace and the modelling was seriously flawed. My evidence to the Court would have been devastating for the Government’s case. But I never got to provide the evidence as it was declared “inadmissable”. This decision by the Court arose after several hours of legal debate which arose because the NSW government and its developer mates (who wanted to get their hands on the public assets) opposed the community group’s use of my evidence. The argument was that because the Report was leaked, any information in that Report could not then be used to develop alternative economic modelling which would be against the privatisation.

There was no claim that my evaluation was wrong – just that nobody could hear it because the Report was leaked. The legal babble was pretty amazing and after two days the judge declared my report “inadmissable”. The Government etc, in orther words, had silenced me using legal technicalities rather than economic arguments, which was where the debate should have been focused.

The community group’s challenge was subsequently defeated and the Government privatised the hospital (it was the the first hospital privatisation in Australia). It was a total disaster.

The service contract gave the monopoly private operater much higher per head care payments that were offered anywhere else in Australia. As time passed, the standard of care fell and the public costs of providing health care in the region rose. The company fighting to make higher profits cut nursing staff further. According to NSW Health Department peformance metrics, under privatisation, the hospital developed one of the longest waiting lists and one of the poorest performance records of all NSW hospitals. The private operator also found it hard to make profits.

Eventually, the NSW government was forced to buy-back the privatised Port Macquarie Hospital. All of what happened was foreshadowed in the modelling I provided in my suppressed Report. It was clear before the privatisation that it would fail because the economic cost-benefit analysis conducted by the NSWTreasury was seriously flawed. When I presented a more reasonable discounted cash flow analysis the privatisation was always doomed to fail (quite independent of your emotional position about public-private ownership). You can read about the failed privatisation here.

Anyway, that was a digression to the main blog.

Back at the interview , Carling replied to the question in this way:

Well they’ve just announced their budget result for their last fiscal year, which ended on the 30th Septmber and that was $US1.4 trillion, or to make it easier to understand in Australian terms, it was 10 per cent of GDP, which is more than double what we are projecting. The really scary figures are in their long-term projections and these are official projections by the Congressional Budget Office, which suggest that under realistic assumptions, they could be looking at a deficit of 15 per cent of GDP 25 years from now and 22 per cent of GDP in 2050 with a public debt burden as a multiple, several times of their gross domestic product.

The most recent 10-year budget projections from CBO were issued in August 2009 in The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update, where the CBO said

… that, as the economy recovers, if current laws and policies remained in place, the deficit would shrink but remain above $500 billion per year, or more than 3 percent of GDP, throughout the 2010-2019 period. As a result, debt held by the public would continue to grow as a percentage of GDP during that time. That debt, which was as low as 33 percent of GDP in 2001, would reach an estimated 54 percent of GDP

The CBO also produces highly speculative long-term projections and Carling was presumably talking about the estimates which were summarised in Table 1-2 (Projected Federal Spending and Revenues Under CBO’s Long-Term Budget Scenarios) on page 8 of the The Long-Term Budget Outlook, which were published by the CBO in June 2009 with accompanying data.

The CBO provide two alternative long-run scenarios: (a) “The ‘extended-baseline scenario’ adheres most closely to current law, following CBO’s 10-year baseline budget projections for the next decade and then extending the baseline concept beyond that 10-year window. The scenario’s assumption of current law implies that many policy adjustments that lawmakers have routinely made in the past will not occur”; and (b) “The alternative fiscal scenario” represents one interpretation of what it would mean to continue today’s underlying fiscal policy. This scenario deviates from CBO’s baseline even during the next 10 years because it incorporates some policy changes that are widely expected to occur and that policymakers have regularly made in the past. Different analysts might perceive the underlying intention of current policy differently.”

You can view these assumptions on Table 1-1 on page 2 of the above document. The longer-term projections are largely driven by health expenditures as the US population ages. There is a huge amount of uncertainty about the health care assumptions. I actually think they are probably inaccurate and being driven by the mainstream budget fears that an ageing population is a disaster. So which scenario is more likely is highly speculative but the deficit naysayers focus on the alternative fiscal path as being more likely because they project higher deficits as a percent of GDP.

I say … from the standpoint of modern monetary theory (MMT) … whatever!

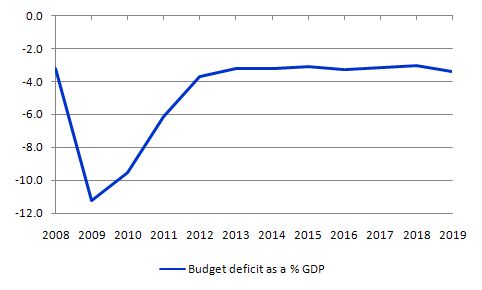

The following graph shows the deficit as a percentage of GDP projections out to 2019 which are heroic enough. It is dangerous to project beyond that given the “political nature” of the assumptions. The data for the graph is from the most recent CBO projections. In my view it presents a more reasonable depiction of what is likely to 2020.

But it is still a case of why should we be focused on the budget outcome, which after all is being strongly driven by the automatic stabilisers in the US at present.

The interview then went like this:

MARK COLVIN: The United States is a big, rich, powerful economy. Can’t they afford that kind of deficit?

ROBERT CARLING: I think that they can in current circumstances because their private sector is on its knees, it’s not investing much and it’s not borrowing much so it’s not competing heavily with the Government for loanable sums. They also have in their favour the fact that the US dollar is still the major currency and there is a strong demand from countries like, surplus countries like China for US Treasury securities. But they can’t rely on all of these conditions continuing.

So what does Carling know about how a modern monetary economy such as the US works? Answer: nothing.

First, the US government is sovereign in its own currency – it can always afford whatever deficit arises.

Second, the affordability is not related whether the private sector is “on its knees” or not. The size of the deficit is influenced by whether they are on their knees or not but solvency is not a question.

Further, when we ask the question what can a government afford we always focus on the wrong (totally erroneous) construct. The numbers Carling thought would be scary are just numbers that arise from an accounting system. These numbers are not economic costs. MMT tells us that costs are real constructs which means that the government can afford to buy whatever real goods and services are offered for sale.

Third, the fact that the parts of the private sector are now attempting to repair their balance sheets after the decade of credit bingeing is a stabilising trend. The fact they are not borrowing much at present has no implications at all for the capacity of the US government (or any sovereign government) to spend. Absolutely nothing at all. Carling is just plain wrong to think otherwise.

There is no store house of “funds” that the government is borrowing from that is now larger because the private sector is not borrowing. The private banks will lend to anyone who is credit worthy and is certain that their investments will provide robust returns. Loans create deposits and the reserves are added afterwards.

Further, the federal government is just borrowing back the reserves it created with the deficit spending. Even if private sector borrowing increases as confidence returns, there will be no shortage of “loanable funds”. The private sector may decide they want less government paper which means that yields on government debt will rise (as demand falls).

But this is just because of the nonsensical arrangement that the Australian government voluntarily imposes on itself whereby it auctions of debt to the private sector to match $-for-$ its net spending. The rising yields are nothing intrinsic to the government spending. They typically suggest the private sector is feeling better and as they translate that into higher spending, the deficit falls anyway via the automatic stabilisers.

The China argument is nonsense, but because it resurfaces in the interview I will deal with it later.

The interview then continued (I left out a stupid interchange about Japan and Italy):

MARK COLVIN: So are you saying that the United States is really going to rely on other countries to bail it out – China in particular – and will that happen?

ROBERT CARLING: They certainly will be depending on those surplus countries to continue buying their US Treasury securities. Whether that continues to happen depends on a host of factors but it’s a very risky proposition to maintain that dependence and I think that countries like China would really be doing the US a favour if they curbed their demand for US Government securities.

The spending by the US government is not reliant on China buying its securities at all. The US government spends in USD. The Chinese government doesn’t issue USD nor send any to the US Government so it can spend them. The Chinese government is desiring to accumulate financial assets in USD as part of some strategy they are following (to keep their exchange rate low and help net exports).

The only issue about that is why would the Chinese population want its government to be exchanging China’s real resources (which could be consumed domestically) for USD-denominated financial assets. The claim that China could close down the US government’s capacity to spend is a non-issue – it just reflects the ignorance of those who make such statements.

What would happen if the Chinese stopped buying US government securities? Well for a start they would have huge USD-denominated bank reserves earning nothing and still be net shipping real goods and services to the US. If demand for US treasuries fell then yields rise and they become more attractive for other investors. Meanwhile the US government would continue net spending.

The sensible thing for the US would be to change laws and stop issuing treasuries at all. But that is not likely to happen. But what is clear is that what China decides in relation to its investment in foreign-currency denominated financial assets presents no constraint on the capacity of the US government to spend.

Repeat after me three times and repeat it every morning when you first awake: China does not fund US government spending.

The interview then continued:

MARK COLVIN: So they need a short, sharp shot, the Americans?

ROBERT CARLING: Yes and shock US politicians into acting more swiftly on this deficit problem.

They have had a very sharp shock already and that is why the budget deficits increased in the first place. A significant increase in US government net spending is being driven by the automatic stabilisers – that is, the endogenous response to a failing economy – tax revenues falling and welfare spending rising.

The first misconception, just to reinforce my earlier comments, is that the Chinese cannot give the US economy a short sharp shock of the sort that Carling is implying by stopping by US government treasuries. As above.

But if the US government attempted to use discretionary policy changes to act “more swiftly on this deficit” outcome then they would only create the conditions for an even higher deficits in the future. Why? Because unemployment would continue to rise beyond its already catastrophic levels (see this blog for a reminder). Further, more firms would close and never reopen and the long-term potential growth potential of the economy would decrease as productive capital was trashed by these disappearing industries.

It would just entrench much higher deficits as the automatic stabilisers turned harshly against the US government. What does Carling think is the growth path out of that sort of malaise? What are his unemployment projections that would accompany this sharp shot? He clearly doesn’t understand the dynamics of government budgets.

Further, it is unlikely that a further sharp shot would be short. The US economy has been in decline since December 2007. There is limited private sector job creation occuring and the banks are still in a fragile state. The commercial real estate debt overhang has not yet unwound and there is still some way to go cleaning up the residential real estate mess. Any attempt by the US government to wind back now would further stall any private recovery. It would be an act of gross vandalism on the part of the government to attempt this.

The major issue is why is the US Government delaying a further discretionary increase in net spending? It is desperately needed.

The bias in the interview is demonstrated by the fact that interviewer didn’t pursue Carling on these issues. Why did Colvin not seek comment on the rising unemployment and underemployment in the US? Why didn’t Colvin force Carling to explain the budget dynamics rahter than just allow him to deceive the listeners with falsehoods?

The interview continued (leaving out a stupid interchange about interest payments):

MARK COLVIN: You seem to be suggesting a crisis is coming unless they wake up pretty fast and yet all the signs, the global signs seem to be that the recession is, if not over at least coming towards an end. It doesn’t look as if anybody is going to wake up does it?

ROBERT CARLING: That is the short-term view and probably politicians with the focus on the short term are not confident that they are going to face up to this longer-term budget problem and they may get some support for that in the next few years because some of these temporary factors that have pushed up the US budget deficit will moderate. So it may appear that the problem is coming under control. But that will be a false impression because these longer-term problems – the demographic change, the ageing of the population, the relentless growth of health-care costs in the US – they are all longer-term problems ticking away there like a time bomb for the future year’s budget.

The longer term issues – the ageing debate, health care etc – are all political debates that should be fully explored. But whatever is decided politicially, there will be no intrinsic financial constraints on the US Government.

If the US population decide, politically, that they want to improve health care for older Americans then they will require the US government to take spending decisions that will be consistent with that. The US Government will always be able to implement those politically-resolved spending decisions, unless, of-course, American runs out to real resources, which is implausible.

If that requires a reallocation of total resources towards, say, health care then that will be resolved politically. If the economy is at full capacity (in real terms) then the political process will have to mediate those changes. In that event there will be losers (those who are no longer able to access the diverted resources) but all that will be a political process.

Whether the government has been running large deficits or small deficits relative to GDP will not make any difference to its capacity to provide budget support to the political process.

However, what is also clear is that the public resources that will be required to provide this future care will be larger if the government tries to run surpluses (or reduce deficits) now as a contrary move to the desires of the non-government sector in the US to increase their saving ratio.

The best thing that the US government can do is to “finance” the non-government desire to increase its saving ratio – by running deficits consistent with that desire – and maintain high employment levels. Then the private sector will be better placed to fund their own health care in the future. A depressed economy with an inability to increase private saving is unlikely to be able to afford adequate private health care and hence the responsility for this provision will fall back onto the public sector.

Why didn’t the interview cover those issues?

Finally, the interview turned to the relevance of all this for Australia:

MARK COLVIN: How much of this is a problem for Australia? We seem to be increasingly decoupled from the US economy and coupled more to the Chinese economy.

ROBERT CARLING: Well there would be two implications for Australia. The US may become less of an engine of growth for the world economy in the future than it has been over the long term. Obviously it’s not an engine of growth at the moment, but taking the long view over history it has been. It may be less of that in the future if these large budget deficits drain capital away from the private sector and damage productivity growth and the growth of the US economy. It’s likely to become a more sluggishly performing economy and that will have implications because of its size for the global economy. Also, Australia, long-term interest rates in Australia depend in significant part on global conditions and if the US and other countries, I should say, it’s not just the US, but other countries, especially in Europe, their big budget deficits, their big borrowing requirements drive up long-term interest rates in the future, there’ll be some spillover effect of that on Australia.

I have not listened to the interview but I am sure Carling was breathless as he tried to get as many of the scare slogans into his last response. I guess he ran out of breath before he got to the inflation bogey.

The large budget deficits will not drain any capital away from productive investment. As soon as there is a confidence in the capacity of the economy to support returns on productive investment it will happen. Banks will create loans when there is a demand for them from borrowers. That demand is likely to rise if there is sufficient budget deficit support to underpin a return to growth.

Further, the central bank sets the short-term interest rate which conditions the term structure and the longer duration rates. Calring should study Japan to see what happens in a modern monetary economy when governments run large deficits, borrow large sums, and the central bank targets a zero interest rate. He clearly doesn’t understand what happened there and why?

Conclusion

I received some other E-mails this morning which contained reports that legislation to extend unemployment benefits is stalled in the U.S. Senate amid a partisan dispute over how to finance the plan. The republicans want cuts to “pay” for the move. Idiots. Why don’t they understand they will have a bigger problem on their hands for longer in this regard (higher unemployment) if they try to cut federal net spending now?

The real question is why do my friends do this to me? (send me such E-mails?). Answer: they know I will just find the reports anyway – so they are saving me time. Aren’t they considerate.

Anyway, it is very early over here and it is time to go running into the cold morning Almaty air – currently 2 degrees celsius. Landlocked and freezing … and the day ahead is about managing revenue from resource exports. Fun ahead for me.

“The major issue is why is the US Government delaying a further discretionary increase in net spending? It is desperately needed.”

I know you are asking this question as an economist, but the answer is a political one: The major issue is that the current group of ruling politicians are afraid of a populist backlash.

I think more Americans would be willing to go along with higher deficits if they understood why they were necessary and if it could be shown that the current US administration is sincere in wanting to help those hardest hit by the downturn while at the same time causing the least damage to those who have not been as affected. Instead, the current administration — in my opinion — is increasingly fomenting distrust from the general US populace.

It is not helpful for his trust that Mr. Obama to continually apologizes for the US. Nor is it helpful that he has not done much to deliver on his promises of increased legislative transparency. Nor the proliferation un-elected “czars,” the unfolding corruption scandals of many of his associates (ACORN, Blagojevitch, etc.), the communist sympathizing of many of his associates, or the lavish vacations he has been frequently taking. Add to these things the continuing bailouts of firms like Goldman Sachs who then turn around and announce “record profits” while +500,000 jobs are still disappearing every month.

Unfortunately, I am also of the opinion that if indeed the current US administration were to increase it’s net spending, it still wouldn’t help the unemployed — instead, it would be just like the first “stimulus” bill, where most of the money would be set for release years in the future and targeted to earmarks and political favors.

In explaining modern monetary theory (MMT), I think you are right to simplify the number of sectors in order to explain the flows of currency. However, when you de-aggregate, when one starts to get into the details of who in the non-federal-gov’t sector receives the newly issued currency, then many questions arise. If politicians could be trusted to spend in ways that preserve and protect the freedoms of the populace while still helping those in need, then I think the increase in spending could be politically feasible. But, if there is any political candidate talking like that in the US, he or she is not well known.

I know you are trying (rightly) to focus your blog on economics and not politics or opinions. But, the fact is, what we in the US need is real change and for people to go along with change, they need to trust the champion of that change. That is increasingly a big hurdle for the US.

— Aside —

By the way, as someone who has lost his job more than once, let me make clear that I am very sympathetic to the plight of the unemployed. I think the idea of the “job guarantee” (as I understand it today) is far superior to current welfare and unemployment benefits policies in the US. From a behavioral science perspective, it is important that people receive pay for work performed, instead of receiving pay for doing nothing. It is psychologically much healthier. I also think the concept of “job” is ripe for deconstruction, but that’s a whole different issue.

— /Aside —

— Phil

Hi Bill,

I minor technicality. There is something about your blog which shows up differently in Internet Explorer. In Firefox this post appears fine but in IE, after (and including)

for a reminder). Further, more firms would close and never reopen and the long-term potential growth potential of the economy would decrease as productive capital was trashed by these disappearing industries. …

everything appears as a hyperlink. Also when you use bullet points (elsewhere), they don’t appear in IE – the bullet symbols.

Thanks Ramanan – fixed now. IE should be banned from the planet for its attempts to redefine the WWW standards (introducing its own rules) and thus render them proprietary. But the problem with the blue link in this case was a coding error by me. The dot point problem is more intrinsic to the way IE distorts the standards and that requires some more css hacks (as they say) which I will look into when I get home next week. But I hope people are sensible enough not to use any version of IE.

best wishes

bill

“the communist sympathizing of many of his associates”

I try to keep pretty close touch on the Obama news – I’ve missed that one.

It’s amazing how just a few words can destroy credibility and render an entire comment meaningless.

“I try to keep pretty close touch on the Obama news – I’ve missed that one. It’s amazing how just a few words can destroy credibility and render an entire comment meaningless.”

Perhaps my comment did venture too far into the political realm for this blog. I did so only because the political situation is definitely affecting the economic choices made by the current US federal government. It is an issue related to trust.

As for the “communist sympathizing” comment, I was referring to associates such as Anita Dunn, who has said (paraphrasing) that Mao Tse Tung is one of her favorite philosophers. Whether you agree with that sentiment or not, the fact is that many in the US would and do feel uncomfortable by such admission. You can look up (if you like) other associates such as Van Jones, Bill Ayers, Cass Sunsteen, etc. (If you do, may I suggest British or Canadian news media — they tend to act more like journalists than the US news media.) Such sentiments, I think, are contributing to a growing lack-of-trust problem for the current US administration.

Note: I specifically did not say that Mr. Obama was a communist. I am not aware of him saying anything that would suggest that he is so inclined.

Interestingly, Mr. Bush had a similar problem during his presidency, but for different reasons. Maybe it is time for a third party to have a go at governing?

Because one has “associated” with someone does not mean those people are “associates”, certainly not in the way you imply.

And, of course, you did not say that Mr. Obama was a communist – but certainly that was the intention. Why else focus on his “communist” associations, and not the more influencial associations with financial interests, neo-liberal political interests, pharmaceutical industry interests, etc.?

Were you trying to imply that such “communist” associations had more sway over his intentions than say, Lawrence Summers or Tim Geithner or Ben Bernanke? Where did Bill Ayers end up in the Administration, by the way? Do you seriously believe this is the source of Obama’s public perception problems?

The lack-of-trust problem Obama has in the US has everything to do with the fact that he was elected under a very-nonspecific but clear mandate to act in accordance with the interests of the public, but once in office has taken actions that have been anything but. In fact if Obama actually put himself on the line to support something that could remotely be construed as “communist” – such as a public option in the health care reform – his ratings would increase.

Now, if you were implying that the right-wing news media outlets in the US are misconstruing policy decisions as “communist” to encourage opposition to Obama’s neo-liberal policies, then I strongly agree and I am sorry I missed the irony.

Visiting the British (I assume the Daily Mail or the Murdoch-Times) or the Canadian press (National Post, Toronto Star?) would be instructive, but if your point is that the US public lacks trust in Obama, it certainly is not due to their reading of the foreign press.

And while I have no idea as to what similar “communist” problems Bush made have had, I also have absolutely no desire to find out.

“And, of course, you did not say that Mr. Obama was a communist — but certainly that was the intention. Why else focus on his “communist” associations, and not the more influencial associations with financial interests, neo-liberal political interests, pharmaceutical industry interests, etc.?”

My intention was to focus on perceptions of him and not on his intentions. I think the “associates” that I mentioned are more influential towards shaping the lack-of-trust perception than Larry Summers or Tim Geithner. If I thought Mr. Obama’s problem were a lack-of-competence perception, then I would have mentioned Summers and Geithner.

Frankly, I think you understood my intention but are being defensive.

However, this comment is interesting: “In fact, if Obama actually put himself on the line to support something that could remotely be construed as ‘communist’ — such as a public option in the health care reform — his ratings would increase.” Maybe, maybe not. However, if a public option in health care reform is passed with anything other than ordinary voting procedures (and the understanding that the congresspersons actually did read the bill before voting on it), then the lack-of-trust perception will be greatly exacerbated.

(In my opinion, Mr. Bush had more fascist than communist perception issues due to polices such as the Patirot Act, the increased tax penalties for expatiration, and the TARP bailout. You may consider these policies very different from Mr. Obama’s policies, but they factored in to a lack-of-trustworthiness perception.)