I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Chill out time: better get used to budget deficits

The latest economic news from the UK and the US is hardly inspiring. Further, detailed examination of the sectoral balances in the OECD nations reveals a massive drop in private demand since 2007. The mirror image of that spending collapse has been the increase in public deficits via the automatic stabilisers (discretionary stimulus packages aside). These swings are just signs that economies are adjusting back to more normal relations (private saving, public deficits). The sharpness of the swings reflects the atypical period that preceded the crisis where growth was fuelled by private debt in the face of fiscal contraction. It will take some years for the adjustment to be completed and the danger is that ideological attacks on the fiscal deficits will derail the process. But when the sectoral balances return to more normal levels in relation to GDP then guess what? We will still have budget deficits and we all better get used to it.

In that context, I can see the development of a new industry – psychological support services for deficit terrorists – which will help them make the transition back to happiness once they realise deficits are here to stay. Any entrepreneurs out there want to licence this idea from me? (-:

Anyway, to the data first …

The news from the UK is that it “may not have emerged from recession after all”. The revised GDP figures come out today and based on yesterday’s investment data there is a real possibility that the UK has remained in recession during 2009 despite the earlier positive growth figures for the fourth quarter.

So while we have been thinking a double-dip is on the cards, particularly as the electoral cycle drives mad fiscal austerity programs, the fact is you cannot double-dip until you have finished dipping once!

The UK Office of National Statistics released the Business investment, Provisional results – 4th quarter 2009 yesterday (February 25, 2010) which showed that:

Business investment … for the fourth quarter of 2009 is estimated to have fallen by 5.8 per cent from the previous quarter and is 24.1 per cent lower than the fourth quarter of 2008.

The following graph shows real business investment in the UK (seasonally adjusted) since the first-quarter of 2007. This is a lengthy and dramatic decline in spending. In case you don’t realise the significance of this – that spending supports output and jobs – it has gone!

One of the implications of this investment free-fall is that the growth in potential capacity will be much lower when the overall economy finally resumes growth. This is the hysteresis effects that I outlined in this blog – The Great Moderation myth.

It is one of the costs of not ensuring that your fiscal interventions are large enough to restore private sector confidence. So when all these political leaders have been falling into the deficit hysteria mantra and assuring us that they would be invoking fiscal austerity strategies in the coming year – all that was telling private investors (that is, the real investors who build productive capacity) was that demand would probably deteriorate even further and so why create new productive capacity.

It becomes a vicious circle – private spending declines – the automatic stabilisers drive up the public deficit – the deficit terrorists go crazy and because they have control of the media create political pressures for the government – the government runs scared and announces austerity – private spending declines further on the news – the automatic stabilisers drive up the public deficit and so on.

What this also means is that private UK economy will not be able to respond rapidy when the rest of the world starts growing – Why? because they have trashed significant volumes of productive capacity.

Madness.

And imagine what is going on in Greece, Ireland and Spain? How are they going to get out of the spiral that their artificial monetary system (the EMU) has imposed on them? Not without significant human suffering and deaths that is for sure. And all for a lousy and mindless monetary system that the economic gurus told the citizens was in their best interests. It never was in their best interests even in the growth period. Now the citizens are seeing that they are still being spun the same lies from the technocrats in Frankfurt and Brussels who wave reports from economists in their face as authority.

Total madness.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics released (February 23, 2010) its latest mass layoffs data which showed that:

Both mass layoff events and initial claims increased from the prior month after four consecutive over-the-month decreases.

In other words, not a lot is happening in that labour market that is positive. A double-dip is very likely now without further stimulus support.

Other headlines today – among others:

“Downgrade from Moodys could prevent Greece from swapping its bonds with the European Central Bank as collateral for loans” – (Source).

“Investors spooked as Fed says it is investigating role of Goldman Sachs and other companies in Greece’s debt dilemma” (Source).

“More than 20,000 people took to the streets of Athens to demonstrate against the Government’s austerity measures (Source).

Conclusion: there is nothing in the financial and economic news that is signalling that the crisis is over yet which brings me to a piece written last Tuesday (February 23, 2010) by Financial Times economics writer Martin Wolf entitled – The world economy has no easy way out of the mire.

To which a three word response might suffice – no there isn’t. But you will want more from me than that.

Wolf said:

Anybody who looks carefully at the world economy will recognise that a degree of monetary and fiscal stimulus unprecedented in peacetime is all that is prodding it along, not only in high-income countries, but also in big emerging ones. The conventional wisdom is that it will also be possible to manage a smooth exit. Nothing seems less likely …

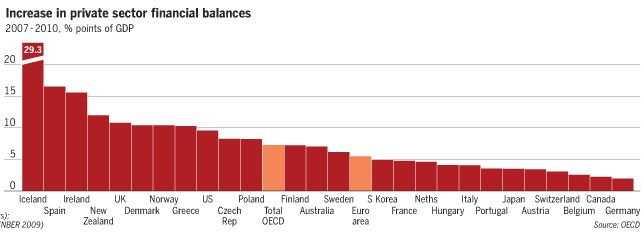

He then referred to the following graph (which I captured from his article). It is from the OECD Economic Outlook and shows that the private sector in many nations “is now spending far less than its aggregate income”. This is one of the sectoral balances I refer to regularly.

Wolf summarises the OECD analysis of the graph saying that:

… in six of its members (the Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden, Japan, the UK and Ireland) the private sector will run a surplus of income over spending greater than 10 per cent of gross domestic product this year. Another 13 will have private surpluses between 5 per cent and 10 per cent of GDP. The latter includes the US, with 7.3 per cent. The eurozone private surplus will be 6.7 per cent of GDP and that of the OECD as a whole 7.4 per cent.”

That is a massive reversal from the period that preceded the crisis. The shifts shown for the period 2007 to 2010 are dramatic and unusual by historical standards but just as dramatic and atypical was the period that preceded it when private sectors gorged themselves with debt.

And … just as dramatic and atypical … was the fact that this debt fuelled economic growth (in construction and real estate etc) which generated tax revenue beyond normal levels and allowed national governments to run budget surpluses.

So while all the tecnocrats in the EMU, the IMF, the OECD and in economics departments around the World were applauding the budget surpluses and proclaiming an end to the business cycle – problem solved – the Great Moderation – the reality was very different and these goons were too ideologically blinkered and stupid to realise it.

All the macroeconomic trends in the last decade or so have been atypical and we are now seeing the adjustment swinging back to more normal sectoral balances – except in the process of adjustment we are getting very large opposite swings – like the move back into overall private sector saving shown in the graph, which is very strong.

The resulting swing in public balances (into deficit) have also been very quick and large by historical standards. But modern monetary theory (MMT) understands these swings are part of the adjustment back to normality – painful as it is.

The swing to private saving was of depression-creating magnitudes. Any economist with job tenure or similar who claims the fiscal interventions were unnecessary (as in Barro yesterday) should offer to resign immediately if they cannot tell us how unemployment would not have risen even more sharply in the face of this private spending contraction. What would have filled the spending gap if not fiscal policy is the question they have to answer?

And … they should therefore tender their resignations and join the queue to see how much they like the “pursuit of leisure” (which is how they characterise unemployment in their textbooks).

So the adjustment process we are undergoing – some private debt payback, private saving and public deficits – which is the normal pattern for a healthy growing economy – will have to continue indefinitely.

Wolf however is concerned with how we exit the malaise. He considers that you need to understand “how we entered” the malaise to fully appreciate the solution. I definitely agree with that.

He then discussed whether loose monetary policy caused the lax credit and resulting asset bubbles which is one of the mainstream claims. I provide a critique of those claims in this blog – Monetary policy was not to blame.

The claim is also tied into the current mis-debate about the likelihood that the buildup in bank reserves will be inflationary. They will not be and I cover that argument in this blog – Building bank reserves is not inflationary.

The point is that the growth strategy based on increasing private sector debt, “the explosion of the balance sheet of the financial sector and increase in its exposure to risk” and the “soaring consumption of durables in high-income countries and booming construction of housing and shopping malls in countries such as the US” etc – was never sustainable despite what governments and their economic lackeys were saying during the “boom”.

It is also clear we cannot go back to that strategy. Private deleveraging has to continue and private spending has to be supported through income rather than credit growth.

If we allow the financial sector to go back to past behaviour then it will just foreshadow the next major financial and real economic crisis.

So what then?

Wolf says that:

I can envisage two ways by which the world might grow out of its debt overhangs without such a collapse: a surge in private and public investment in the deficit countries or a surge in demand from the emerging countries. Under the former, higher future income would make today’s borrowing sustainable. Under the latter, the savings generated by the deleveraging private sectors of deficit countries would flow naturally into increased investment in emerging countries.

Under either scenario, fiscal deficits are here to stay as they should stay given the historical behaviour of the sectoral balance that are now being reasserted most brutally.

The only way that the large nations can grow again given the return to overall private sector saving is for that saving to be supported. What does that mean?

An explicit shift to higher saving directly impacts on aggregate demand. This will cause inventories to accumulate and soon enough firms start cutting back production and employment and the process of output-spending losses them multiplies as the rising unemployment becomes a deflationary force in itself.

The only way the shift to higher saving can be realised without the descent into recession and even depression is for fiscal intervention to fill the spending gap.

The higher incomes support the saving and the deflationary impacts of unemployment are avoided.

The typical pattern of advanced nations is to run current account deficits and support private saving with public deficits. In a modern monetary system that combination of sectoral balances is entirely sustainable and will support economic growth levels that are sufficient to maintain high employment levels.

This growth pattern is also the best for emerging economies who rely to some extent on strong export markets for growth.

But we have to be absolutely clear that this does not mean “exit plans”. It does not mean that we plan to go back into budget surpluses as soon as all the shouting has died down. It means permanent deficits will be required and the public has to be made aware of that and understand that this strategy is the only one that sustain steady growth.

Where a nation can exploit a strong net export position, then surpluses are possible (depending on the strength of the external position and the strength of the desire to save by the private domestic sector. But not all nations (obviously) can run external trade surpluses. So it is a special case.

Continuous public deficits is the general and normal case and they should be directed and building strong public infrastructure include first-class education and health systems. Investing in people is the only durable investment.

And for the Chicago and Austrian School types that are now whipping up inflation fears consider Japan – again – they have growing deficits and are still fighting deflation.

Wolf concludes that:

Most people hope, instead, that the world will go back to being the way it was. It will not and should not. The essential ingredient of a successful exit is, instead, to use the huge surpluses of the private sector to fund higher investment, both public and private, across the world. China alone needs higher consumption. Let us not repeat past errors. Let us not hope that a credit-fuelled consumption binge will save us. Let us invest in the future, instead.

You will appreciate that I agree (mostly) with this summation.

Where I disagree is with his depiction of the causality between the sectoral balances. MMT tells us that public deficits help fund the huge private sector surpluses (through the mechanisms I outlined above) – not the other way around.

Part of the problems were are enduring is that commentators like Wolf continue to reinforce the erroneous notion that national currency-issuing governments are financially constrained and need to be “funded”. They don’t and as soon as we understand that we will be able to see more clearly why the crisis occurred – that is, the role played by the budget surpluses – and how we stay clear of crises in the future.

The FT graph demonstrates clearly the way policy has to go. Budget deficits will be required indefinitely and we better get used to it. All the exit plans in the world cannot deny this reality.

Austerity packages will just be the acts of ignorant vandals who are committing crimes against humanity by unnecessarily impoverishing their citizens and increasing suicide rates and all the rest of the pathology of unemployment.

What is desperately needed in all economies (EMU included) is a very substantial new fiscal injection. Several percentage points of GDP will be required in most countries including Australia.

Failure to do that will ensure very slow growth if at all and the real danger of slide back into recession and more havoc.

Meanwhile … back in Washingon

Bernanke spills the beans!

The US central bank boss appeared before the House Committee on Financial Services on Wednesday, February 24, 2010.

After various speeches and presentations were made, the Q&A session started and at 41.05 minutes into the televised proceedings you will see and hear this interchange:

Chairman Barney Frank: We hear this threat that the rating agencies might reduce our debt rating because of the deficit … Do you think there is any realistic prospect of America’s defaulting on its debt in the foreseeable future?

Bernanke: There certainly … Not unless Congress decides not to pay which I don’t anticipate. I don’t anticipate any problem …

Chairman Barney Frank: There is not a fear of default!

Okay, sovereign governments will not default on its national debt unless the legislative body “decides not to pay”.

Major deficit terrorism scare put to bed!

Counselling support services will be needed to help them adjust to this!

End of story.

Meanwhile in the banking sector

Consider the following scenario – in 2002 an organisation is “censured” by the authorities for money laundering. In the ensuing years it becomes a major predator in its industry causing havoc to other firms.

The organisation then posts record losses and the government assumes 84 per cent ownership as a strategy to stop the industry collapsing due to the incompetence of the management of this and other firms like it.

It is also reported that the organisation is under investigation by the regulative authorities for money laundering and suspicious funding of take-overs and poor handling of customer complaints.

A major real crisis then emerges as a result of the incompetence and dishonesty of the management in this industry – major unemployment arises – poverty rates increase, whole countries face serious austerity campaigns, and the mainstream economics profession goes into hiding (but as you know they emerge soon after the government has stopped the free-fall – and are as arrogant as ever).

Since being publicly-owned the current management of this organisation also fail to meet the own lending targets agreed with government as part of the bailout.

And … at the height of the losses in the organisation … the public reads this headline in the national daily newspaper – Bank loses £3.6bn – but finds £1.3bn to pay bonuses.

That is about as crazy as it gets. It must be some bad dream!

But The Times article reported that:

More than 100 bankers at Royal Bank of Scotland will take home bonuses of at least £1 million even though RBS, 84 per cent-owned by the taxpayer, made a £3.6 billion loss last year.

At least two employees in RBS’s investment bank will receive about £7 million each, the bank revealed yesterday as it reported a near-doubling of bad debts to £13.9 billion in 2009.

And what did RBS say by way of defence? The chairman claimed they were conflicted by “being deeply loss-making and relying on government handouts” but also having to face the “realities of running the business.”

And what might those realities be – given they are not really running any business but supervising public money and transferring significant portions of that public money to their own bank accounts via share bonuses?

The RBA chairman also said they were only trying to pay:

the minimum necessary to retain and motivate staff …

Here is some logic to help us work through this imbrolgio.

In economics there is the concept called economic rent. The rent component of a person’s remuneration is the difference between their current pay and the minimum amount that they would supply their labour for to do what they are doing at present. If minimum pay is lower than the current remuneration then the worker is receiving rents which are unnecessary to elicit supply.

Eliminating the rent component – for example, by a tax – would thus not alter the supply of labour.

Question: How many financial market workers would be prepared to go to the office on a daily basis and make extravagant gambles that they had no chance of assessing properly; create ridiculously complex products and foist them onto innocent third parties just to maximise return; and wave ten pound notes out their windows to demonstrators who were just expressing their concern for the future of the planet – and – receive lower pay?

Answer: (its only a Barro-type guess) … lots.

Implication: The claim by the RBA chairman that there are zero rents in this industry – given his statement above – is likely to be false.

Solution: impose substantial taxes on them to eliminate the rents.

I had this old-fashioned idea that “performance bonuses” were paid if you did a good job. You know – make a profit if you were a capitalist firm, or helped society in some way by increasing employment and reducing poverty.

But I admit now I was totally wrong. It is clear that peformance bonuses vary in some inverse way with the level of incompetence you bring to your job and the amount of damage you inflict on others through the products you create.

And finally … poor Peter

… should have stuck with Midnight Oil.

Saturday Quiz

Yes, another week down and its nearly time for the Saturday inquisition. Look out for it some time tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

On “poor Peter”, psephologist Possum commitatus does something that no-one in the media has thought of doing so far – checking to see if there actually was any stuff up or whether hysteria has taken over.

http://blogs.crikey.com.au/pollytics/2010/02/24/did-the-insulation-program-actually-reduce-fire-risk/

Dear Bill,

Fully agree with you about Martin Wolf’s deplorable article.

But no one is perfect: I’d like to correct one of your sentences. You say “Continuous public deficits is the general and normal case and they should be directed at building strong public infrastructure include first-class education and health systems.”

I suggest that the fundamental reason for continuous deficits is, as I pointed out a few days ago, the fact that given modest inflation (say around 2%) and given constant private sector desired net financial assets in real terms, a continuous deficit is needed to maintain the latter in real terms.

Determining the optimum amount to spend on infrastructure, education and health is completely separate from the deficit.

Best wishes, Ralph.

Bill,

I was reading Marshall Aurbach”s piece this morning on Naked Capitalism and noticed that Japan is used as an example which ever side of the argument one resides on. Your contention is that Japan is proof Sovereigns are not revenues constrained unless they choose to be, and that the bond markets are of no importance. A lot of the critiques of Marshall’s column were of the opinion that Japan has only been able to get away with this due to the health of it’s export markets etc. If you have a moment could you comment on this or direct me to a past blog.

Thanks.

Am willing to accept that there is no risk of sovereign default or inflation in Japan. OTOH, it seems that they have concreted the entire country over with infrastructure spending (some of it of very dubious lasting value). Why is Japan seemingly unable to pull itself out of a two decades plus malaise even with big public deficits?

Hi nmtdoc

That’s a typical response to the “look at Japan” argument of MMT’ers.

There are several points to make in response, but I’ll just make one here that I haven’t seen elsewhere:

As described by the financial sector balances, there are two possible ways for a government deficit to accompany a non-govt surplus–a domestic private sector surplus, or a current account deficit. Those are the only two possibilities, by accounting, or some combination of the two. US and Japan represent the two extremes . .. Japan’s government deficits have been largely accompanied by domestic private sector surpluses, while US govt deficits had been largely accompanied by large current account deficits. That interest on the national debt in both countries has behaved essentially the same–i.e., not responding to the size of deficits but rather mostly following monetary policy–demonstrates at the very least that whether there is a domestic private sector surplus or a current account deficit accompanying a deficit is quite immaterial to how interest on the national debt behaves.

For MMT, the operative factor regarding interest on the national debt is whether or not the government is a sovereign currency issuer (issues a currency under flexible exchange rates), though there are some technical detaisl to add (such as some points whether the govt chooses to default, or chooses to enable operations that allow bond markets to dictate, etc.). The size of the deficit and what sector of the economy has the net saving are not the operative factors.

It’s also worth mentioning that the recent large increase in US govt deficits have actually been accompanied by a sizeable narrowing of the current account deficit and a sizeable increase in the domestic private sector’s net saving. That is, as MMT’ers generally predicted, as the US govt ran larger deficits during the crisis to enable private sector deleveraging, by necessity the breakdown of who has the net saving started to be more along the lines of Japan (so the “Japan has large domestic savings compared to the US” argument becomes less true, and it wasn’t ever actually relevant).

Best,

Scott

You believe that if the government had not run large deficits that the private sector would not have de-levered? Households were forced to continue borrowing, and they were waiting for the government to increase deficit spending in order to “enable” them to stop borrowing?

Clearly the government deficits have enabled certain portions of the private sector to accumulate more financial assets than they otherwise would have, particularly holders of bonds that were at risk of default. But government actions have not “enabled” de-leveraging, they have attenuated it. Without the deficits there would have been a wave of defaults and very rapid de-leveraging that would have occurred to a greater extent than what we see. The government deficits were attempts to minimize and slow down de-leveraging, not to “enable” it.

RSJ . . .I was just describing the accounting. The non-govt sector can’t net save unless the govt sector runs a deficit. Some within the sector can deleverage, but they would be offset by leveraging of others absent govt deficit. Regarding enable vs. “attenuate,” I think you’re being too picky in your critique of “enable” . . . I meant it again in the accounting sense (that is, if the govt sector had raised taxes, etc. as the non-govt sector tried to net save . . . ), but the way you described the actual process is fine with me.

..and I would add that this is why Japan has been stuck with zero NGDP growth for so long, because the deficits were successful at delaying the de-leveraging process, which could have been completed in a month if the government had truly used it powers to enable de-leveraging.

Instead, they got 2 decades of stagnation and a wealth transfer of almost 2GDPs from the government sector to private sector asset holders, as the government replaced private liabilities with public ones.

No, if I go through a bankruptcy procedure or default on debt, then I have de-levered and this de-leveraging has not been offset by anyone else.

Only if the government steps in and makes my creditors whole is my de-leveraging offset by someone else (the government’s). But whether or not the government makes creditors whole, the de-leveraging will occur, even in an accounting sense.

“No, if I go through a bankruptcy procedure or default on debt, then I have de-levered and this de-leveraging has not been offset by anyone else.”

If you default, then your counterparty writes off the asset and writes down equity.

“Only if the government steps in and makes my creditors whole is my de-leveraging offset by someone else (the government’s). But whether or not the government makes creditors whole, the de-leveraging will occur, even in an accounting sense.”

The opposite is true, actually. If the govt steps in and makes the creditors whole, they have not lost equity, and net financial assets are increased. If the govt doesn’t step in, then the defaultor loses the liability w/ no loss of equity (increase NFA) and the creditor loses the asset with a loss of equity (decrease NFA, since no change liabilities).

Scott:

I think RSJ is right. The private sector can delever by itself if it simply pays down debt (both asset and liability and debited, equity remains the same, hence leverage is smaller.) If the private sector writes down debt, the asset and equity liability is debited on bank side, but borrower retains their own equity. Not sure what net effect it.

Moreover, you are ignoring real asset, which reduces leverage even though it is difficult to value sometimes.

You are accurate if you say Govt deficit spending has increased net financial asset position of private sector.

“If the private sector writes down debt, the asset and equity liability is debited on bank side, but borrower retains their own equity. Not sure what net effect it.”

The net effect is no change in NFA, as I said at 4:55. Borrower retains own equity, but doesn’t have the liability anymore, so NET financial assets for borrower have increased, and they have decreased for creditor.

Also, the sector financial balances are about FINANCIAL equity. Obviously we leave out real assets; we know that, and we understand the implications. Recall that Greenspan and others said we didn’t have to worry about increased mortgage debt because households had a real asset there (the house). Oops.

Dear RSJ, Scott and zanon

Yes the private sector can delever by itself. It is called mass bankruptcy, loss of asset value and depression. Real assets are then left to decay because there is a limited market for them – have a look at some of the industrial areas in major cities during a recession.

best wishes

bill

Bill . . .yes, but deleveraging in that way doesn’t mean you raise NFA for the sector. I shouldn’t have mingled the two at 4:22. I know the difference, and that’s probably what got us off on this tangent. Apologies.

“It is clear that peformance bonuses vary in some inverse way with the level of incompetence you bring to your job and the amount of damage you inflict on others through the products you create.”

The Chinese way is a bit harsh in my opinion but they do appear to have a different approach on corporate crooks. 😉

“The Hebei Higher People’s Court upheld original verdicts for Geng Jinping for producing and selling poisonous food, and Zhang Yujun for endangering public safety. The two were sentenced to death on Jan. 22 by the Shijiazhuang Intermediate People’s Court.”

People’s Daily Online

“Death penalty handed to Zheng Xiaoyu has fully proven the will and desire of the people across China, eloquently showed the spirit of the fairness and justice of legal sanction as well as the firm resolve of the Party and the state. For corrupt officials, no matter whoever he is, what a high position he occupies and how deep he has hid himself, probes into the cases he is involved will be carried out resolutely and thoroughly, but no indulgence or soft hand will be granted to him.”

People’s Daily Online

Zanon . . . I see your point now. For some reason, as I noted at 7:17, I started saying “deleverage” when I meant to say “increase NFA” at 4:22, and didn’t stop. That’s why my reply to RSJ at 4:55 refers to NFA and RSJ refers to leveraging/deleveraging. I’m right about NFA there, and RSJ’s right about leveraging/deleveraging (and so are you and Bill). Sorry about that. TGIF!

Woah, a lot of pots and pans spinning in the kitchen.

Issue 1: Can the private sector “de-lever” all by itself?

Yes!

Leverage is defined as Assets/Equity = (Assets)/(Assets-Liabilities) = A/(A-L)

Given many entities, each with their own assets and liabilities (A_i, L_i) The (equity-weighted) leverage for the private sector as a whole is:

(equity_1*Leverage_1 + equity_2*Leverage_2…)/(equity_1 + equity_2 + ..)

Private Sector Leverage = (A_1 + A_2 + …. + A_n)/(A_1-L_1 + A_2-L_2 + … + A_n-L_n)

In the denominator, all the private liabilities cancel out, and you are left with the NFA of the private sector (government liabilities held by the private sector).

Therefore,

Private Sector Leverage = (A_1 + A_2 + …. + A_n)/(NFA)

During a default/repayment event (or even as debt is paid down), the NFA is unchanged, whereas as the total assets decrease, therefore private sector leverage decreases — all by itself!

Issue 2: If the government steps in to make creditors whole in the event of default, does this mean that the leverage of the private sector is decreased?

Answer 2: Yes! Swapping one of the assets (A_i) with an asset corresponding to a government liability will leave the numerator is unchanged and the denominator is a bit larger. Therefore the ratio is smaller.

Issue 3: Seeing as how default/repayment causes the leverage to decrease, and that government taking on some private sector debt also causes the leverage to decrease, which operation causes leverage to decrease more?

Government bailout of A_1:

Private sector leverage before = L = (A_1 + A_2 + …. + A_n)/(NFA)

Private sector leverage after = (A_1 + A_2 + …. + A_n)/(NFA + A_1)

Default/repayment of A_1:

Private sector leverage before = L

Private sector leverage after = (A_2 + …. + A_n)/(NFA)

So if L > 1 + A_1/NFA

— which will typically be the case — then default/repayment decreases leverage more than having the government assume the liability A_1. And if this is done in a 2 step operation:

step 1: assets are marked to the level of expected default

step 2: the government comes in supplies enough income or takes the asset on its books

…then private sector leverage *increases* from step 1 to step 2.

Issue 4: Will de-leveraging cause a depression?

No! Those who believe that loans create deposits should not fear this. Government can decrease the numerator all it wants, and also increase the denominator to deal with the shock via jobs programs, a government banking system, government supplied pensions, etc. Such a situation will not create a depression, but will create an opportunity to reform the financial system — something we lost when we backed bondholders. Moreover, it would have put us on a sustainable path of asset levels versus incomes, so that assets are not so great as to not be serviceable out of current wage levels. Financial asset liquidation need not the same as real-economy liquidation.

RSJ . . . agreed! Woot! Woot!

As I noted, somehow I was thinking “NFA” and saying “leverage.” I’m normally very careful about specifying the difference, much as you just did. Sorry for the unnecessary diversion as a result. Also, I don’t think Bill was referring to the deleveraging case with govt stepping in as you suggest in issue 4.

Thank you Bill for realizing that we should tax excessive behavior( speculation) and the economic rents in the bonuses for exploiting complexity induced opportunities.

Ahh, Scott, I didn’t see the previous comment you made. We are in agreement on the accounting.

I know Bill is a good guy and is not advocating direct bailouts. He is fighting the good fight against deficit terrorists trying to scare us, but there are also about the bondmarket terrorists insisting that if we let a bondholder lose a dime, then the world will end in Armageddon. How times have changed since the S&L fiasco when we closed hundreds of banks and only bailed out depositors — not a single bondholder was spared in that action, and yet no depression occurred. The difference in mood now is indicative of how much more financialized our economy has become, and it will only get worse.

The canonical example is Lehman, and how that “taught us” that the economy would end unless bondholders were protected. Therefore we must generate sufficient government income to keep those bonds performing.

I say that you can do an orderly receivership and the real economy will be fine. Only a lot of people will not be as wealthy as they thought they were — so what? Those claims could never be made good given the current wage levels. Even now, they can’t really be made good — we are in the limbo period of extend-and-pretend.

So we have complete freedom to *not* support prices and let a fifth of the mortgage bonds default, let Fannie and Freddie default, let GMAC default, and let most of the banks be put into receivership. Unless you are holding a treasury or a deposit in an FDIC protected bank, your assets should not be protected if your debtors can’t pay. It bothers me that holders of agency debt are receiving yields in excess of treasuries but at the same risk level. No one has a right to pile up claims on their fellows in excess of their wage growth, and then expect those claims to perform. Government pensions and jobs programs can pick up the slack and we can go through the whole process with full employment and a solid social safety net.

RSJ, Scott, Bill et all,

The accounting manipulations do not prove that default/repayment decreases leverage more. I think you guys shold realize that values of productive capacity (nominal capital varies) vary since risk/uncertainty for the economy rises from capital changes as NFA (public liabilities) change. Private liabilities still cancel out but capital has a rising cost to produce because of financing conditions, transaction costs and traditional technical conditions. The rise in NFA from deficit spending covers the financing conditions providing the liquidity cover of uncertainty but unless innovation changes technical conditions the price of capital will decrease and leverage will rise (Remember good old Marx!). In this case public spending will not bring the full employment of resources you target. As I have written in an older comment there could also be a debt leverage spiral effect (MInsky moment).

Nick Rowe has a thoughtful post today, “Fire-and-forget” fiscal policy, on creating efficient and effective automatic stabilizers that would preclude the need for politically messy ad hoc fiscal policy as much as possible. Nick is asking what it would take to accomplish, and what the the proper criteria are.

Henry C. K. Liu wrote an article, summarizing Chartalism clearly, concisely and precisely. He suggests that government can effectively manage the economy to promote the general welfare through fiscal policy, but he doesn’t spell out the details regarding how, since it’s a short piece. He also brings in the external factor – trade, flexible rates, etc, that have an impact on this in an open economy. According to Liu, the US is in a privileged position because of dollar hegemony, and it will fiscal management would work for the US, it would be difficult for others, who must export to accumulated dollar reserves, since only the US can create them at will.

These thoughts have been in my mind for some time, ever since I learned about the possibilities that MMT suggests. But I don’t have the economic chops to address the details in any depth. It would be helpful to get some elaboration on this from economists that non-economists can understand and communicate to others, since these are questions that inevitably come up when people want to know what such a world would look like and how we could get there.

Hi Tom,

That point is an interesting one, but I guess Bill wouldn’t believe if anyone can achieve a fire-and-forget policy. The main reason is uncertainty. Even if policymakers understand how the modern monetary system works and lets assume their training in graduate school is excellent, such a thing may not work in practice. Of course it will be highly beneficial to society if they are well trained.

Firstly, the issues of how the government spends etc keep changing according to time. Also, it will be really difficult for the government to adjust the policy to achieve full employment. Imagine this – there is a period when full employment is not there. The government cuts taxes to stimulate aggregate demand. However it is possible that the increased economic activity leads to higher taxes in $s inspite of lower rates and this leading to a slightly lower demand in the next period. It is really difficult to achieve full employment without the active role of the government and impossible to “automate” the process.

Hi Ramanan,

Nick opines that a fire-and-forget solution may be unreachable but adds: A fire-and-forget fiscal policy is also a good thing for economists to think about. It imposes a beneficial mental discipline on how we think about fiscal policy. If we propose a fiscal policy that would need to be changed in the light of circumstances, we might forget to think about the consequences of those changes, and expected changes. So even if a fire-and-forget fiscal policy is a Holy Grail that we can never find, we might nevertheless benefit from looking for it.

I think Nick makes a good point here for another reason. The objective should be to come as close to fire-and-forget solution as possible because fiscal policy is not only an economic issue but also a political one, and every fiscal move has to be legislated by Congress and approved by the president in the US. This is a slow, cumbersome, and contentious process, as the present state of politics goes to show. It’s pretty well agreed that a second stimulus is necessary and should have been implemented some time ago. But the political process is making that impossible. If we didn’t have the automatic stabilizers in place that we do, the situation would be a lot worse. If they were designed for a situation such as this, all the better. Right now the system is becoming overwhelmed, and the political response is underwhelming.

Off topic here, but Ellen Brown has an article in HellenesOnline, Europe’s small, debt-strapped countries could follow the lead of Argentina, in which she cites Marshall Auerback. Marshall is turning up in a lot of other places, too. These ideas are getting out there.

Roger E. A. Farmer has two short posts, Macroeconomics for the 21st century: Part 1, Theory, and Macroeconomics for the 21st century: Part 2, Policy, presenting what he claims is the outline of a Keynesian solution to future monetary policy through targeting wealth (asset prices) rather than demand. He claims that fiscal policy that focuses on AD and monetary policy that focuses on the overnight rate are not effective, while Fed actions influencing the yield curve that augment the wealth effect through asset prices are.

Interesting proposal, with some typically strange assumptions to make the model work, and flawed in that he clearly doesn’t understand monetary economics, when he concludes, Policies that restore private wealth and private expenditure are superior to fiscal expansions that increase the size of government and place our children and our grandchildren further into debt to overseas investors.

But it it worth looking at in terms of rival solutions to MMT.

I always thought that leverage is _liabilities_ versus assets. And since as liabilities people normally classify financial liabilities so it is fine to divide them by (net) financial assets. And then we get to leverage.

What do you achieve by dividing aggregated assets by net financial assets? I guess it is not a leverage ratio in financial sense or do I miss something?

I wish to associate myself with Sergei’s comment above.

The calculation of macro equity and leverage above is incorrect. The calculation as presented effectively equates macro equity in the denominator to the equity value of net financial assets. This makes no sense as a denominator for a leverage ratio. NFA is a relatively small subset of total assets and makes a relatively small incremental contribution to total macro equity.

Macro equity for the US is approximated in the Fed flow of funds report as household net worth. Household equity includes the embedded value of all business equity by construction. This is because it includes direct equity claims and indirect equity claims. The latter is because it includes direct equity claims on financial intermediaries that hold those indirect claims (e.g. a pension fund that holds stocks and bonds). There is no asset that is not reflected this way in the calculation of household net worth. The only exception to this is the net international investment position of the foreign sector, which is relatively small. Together, the household sector and the foreign sector include all macro equity, including the equity value of MMT NFA:

The approximate numbers:

Household assets $ 67 trillion

Household net worth (equity) $ 53 trillion

Leverage 1.25

Foreign NIIP (equity) $ 3.5 trillion

Total equity $ 56.5 trillion

MMT NFA (approximate) $ 10 trillion (included in total equity)

MMT NFA is a derivation of the sector financial balances model, which itself is a derivation of the national accounts model. NFA is a measure of net financial assets. It is NOT a measure of total macro equity. It is a subset of total equity.

Total macro equity includes net financial assets plus cumulative saving (equivalent to cumulative real investment), marked to market where designated.

Interesting video of Max Keiser interviewing Ellen Brown here. This is important politically in the US because her popular presentation of monetary policy is influential. I am often asked questions about this by friends.

If you are interested in US economic/monetary policy and populism, you may want to take a look. Half is on the problem, and half is on her solution involving state banks on the model of the Bank of North Dakota, the only state bank now operating in the US. Brown is a lawyer and successful author, not an economist, and she seems somewhat confused about the US monetary system, but probably less so that many mainstream economists. Anyway, this is where a lot of people are getting their information.

Dear Tom, Thank you for the Brown article and the Farmer posts. I have ordered the books although I am not in agreement with his arguments. Discovering is my pleasure as I read 10-20 papers in Economics/ Mathematical Finance a m0nth. Between you and me a lot of crap!

Dear JKH,

A drop in capital prices (capital loss) from a rising cost of investment (uncertainty,traditional methods of production, transaction costs) reduces net worth. In order to avoid that and mantain capital prices, liquidity of net public liabilities must be offered from public spending to support the use of existing resources to approximate full employment and furthermore the investment in productive capacity part of the spending is required to come with additional embedded technology/innovation. Any comments?

Panayotis,

Your question is beyond my expertise. It seems to combine asset deflation with input cost inflation. It’s not obvious to me how MMT’ers would prescribe a balanced response to those conditions, but your suggestion seems reasonable.

i think it matters what is increasing the cost of investment. my instinct is to increase demand for investment so that the supply price is lower then the demand price and persue a policy thats cut the rate of cost growth but i will second jkh’s comments that this is beyond my expertise.

As a non-economist (biochemist), I have been following this blog for several months and have been trying to understand MMT. I have yet to find an understandable short summary; would appreciate knowing of a suitable reference article(s)/book. After reading Stephen Zarlanga’s ‘The lost science of money’, and Ellen Brown’s ‘Web of debt’, I got the impression that the common ideas expressed by these non-economists indicated that they (and, perhaps, the economist Michael Hudson who is in some way affiliated with the AMI) may be interested an economic model somewhat similar to that which Bill Mitchell/LR Randell describe(s) as MMT. Is this matter discussed somewhere in the billy blog (https://billmitchell.org/blog/) other than in comments such as those mentioned above?

William, Winterspeak has a very brief summary here. Henry C. K. Liu has a brief summary of Chartalism here. While the article has to do with China’s trade surplus, it is mostly about Chartalism. I suggest you pick up a copy of L. Randall Wray, Understanding Modern Money: The Key to Full Employment and Price Stability (1998). It’s written for non-economists. See Google Books here.

As far as Bill’s blog goes, I would start with In the Spirit of Debate and follow the navigation at the top left to do to the next post. There are three more, for a total of four posts. Bill also structures the links for learning. The first link is to Steven Keene’s blog, where the exchange originated. It contains a good summary of Chartalism by Bill.

Bill is a Chartalist and Steve is a Circuitist. Private debt is more the subject of Circuitism than Chartalism. Circuitism is chiefly concerned with the horizontal (private banking and finance) and Chartalism with the vertical-horizontal (government/non-government) relationship. Private debt arises in the horizontal system of money creation by commercial banks, where loans create deposits. Chartalism is more concerned with using fiscal policy instead of monetary policy to manage the economy than with the commercial banking system. But this is a matter of emphasis. Chartalism and Circuitism are complementary, if correctly understood.

I haven’t read Zarlenga or Brown’s books, but my impression is that they, like Michael Hudson, are mostly concerned with the effects of debt. As I understand it, Zarlenga and Brown put forward proposals to get away from credit in money creation.

According to Chartalism, the way to avoid driving the excessive accumulation of private debt is to balance the sectors contributing to GNP. See Bill’s Stock-Flow Consistent Macro Models, for example. The principle is that government deficit (surplus) corresponds to non-government surplus (deficit), so that if the government budget is in surplus then the private sector is in deficit unless net exports are sufficient to make up the difference. When the private sector is in deficit, then consumers are forced to go into debt to maintain their lifestyle. So, for Chartalists, avoiding this situation is important policy-wise.