I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

IMF agreements pro-cyclical in low income countries

I am researching a new book project at present. I plan with a (development economist) colleague to outline a new development agenda for low income countries. The imposition of neo-liberal policy agenda has artificially and immorally constrained development in the poorest nations. This paradigm is in denial of the opportunities forthcoming to a sovereign government to expand employment and national well-being. We intend to outline a modern monetary approach to economic development as a rival development paradigm. As part of this project, I was reading a research report released last week by the Centre of Economic Policy Research (Washington). The report shows that around 75 per cent of IMF agreements in the current downturn are pro-cyclical. That is we learn what we have always known – the IMF should not be allowed out without supervision.

The research paper:

… looks at IMF agreements with 41 countries. These include Stand-By Arrangements (SBA), Poverty Reduction and Growth Facilities (PRGF), and Exogenous Shocks Facilities (ESF) … [and] … finds that 31 of the 41 agreements contain pro-cyclical macroeconomic policies. These are either pro-cyclical fiscal or monetary policies – or in 15 cases, both – that, in the face of a significant slowdown in growth or in a recession, would be expected to exacerbate the downturn..

Pro-cyclical means going in the same direction as the business cycle. So in a recession, a procyclical policy is one which contracts the economy further – that is reinforces the recession.

Some of the problem arises from the fact that the IMF forecasts for these nations were overly optimistic. The forecasting errors arose because the IMF failed to see the crisis coming. Why?

Easy. Despite it having a huge research capacity the IMF employs economic theory and analytical frameworks which are inapplicable to fiat monetary systems and so the lens through which they attempt to understand the economy is blurred from the start.

Where I see a budget surplus squeezing non-government liquidity and forcing the latter into increased indebtedness to keep the level of spending up and growth going and conclude that a crash is imminent; the IMF sees a virtuous state of government saving and retiring public debt and the non-government sector building wealth. Every six months it releases its World Economic Outlook and we read this sort of analysis from them, as the asset bubble was inflating and it was only a matter of time before it burst.

Further, where I see a budget deficit underpinning social and economic development in a poor nation – providing education, health advances, public infrastructure, employment; the IMF sees a dangerous inflationary bias building up which will release a torrent of speculation on the nation’s currency and social decay will follow.

And again, where I see ships loaded with trees for export and the devastation of a country’s natural eco-system and subsistence agriculture as an anti-development strategy; the IMF encourages export-led growth strategy in every case. It is obsessed with ripping the natural resources from countries and turning sustainable subsistence farming activities into commercialised cash crops. When the world’s supply becomes excessive and the nations start to falter, who else but the IMF steps in with loans. Meanwhile, the subsistence methods become lost because the farms have been turned into machine-laden cash crop centres.

So given the way they attempt to understand the world and tell us about that understanding is flawed at the most elemental level, it is no surprise that the IMF is incapable of foreseeing unsustainable situations emerging. It is also no surprise that they will always invoke policies that constrain and economy from achieving full employment and, instead, propose policies which will never generate sustainable development with high employment levels.

In this context, the Report makes an interesting point:

… the IMF has a history of over-optimistic projections in many countries. So it is not so easy to separate forecasting errors from an underlying bias toward overly restrictive fiscal and monetary policies.

However, we know that the IMF does have an underlying bias towards restrictive policy settings irrespective of their forecasts.

Part of the problem also relates to their obsession with inflation – or expelling it from the system. This obsession dates back to the dominance of monetarism and Milton Friedman in the 1970s and 190s. The IMF thus sees tight monetary policy (that is, high interest rate regimes) as being in some way a safeguard against inflation.

In the current recession this has been especially an issue given the IMF confused the oil price hikes with a permanent upward trend in inflation and pushed tight (procyclical) monetary policy onto nations.

This all might come as a surprise to you given that I have written about the IMF support from the expansionary fiscal policies (and relatively easy money policy) in the current recession – see this blog, as an example.

So what is going on? Well the IMF takes a different view to developing countries. The Report captures it in this way:

The economic argument for this double standard is that developing countries face a much more binding foreign exchange constraint. That is, if they stimulate their economies during a downturn they run the risk of expanding current account deficits and therefore running low on foreign exchange. Countries with hard currencies (the United States, Eurozone countries, Japan) do not face the same constraint, and of course the U.S. has the added advantage that the U.S. dollar is the world’s key currency. However, developing countries that have sufficient reserves are in very much the same position as the high-income countries.

This is backwards reasoning. I should note at the outset that the CEPR, while sympathetic to a progressive policy agenda is still very much wedded to the deficit-dove approach, that old-style Keynesians follow. They see the need for deficits sometimes but worry about public debt issuance (fail to understand why it is issued) and have nonsensical rules that debt-GDP ratios should be stable. In turn, these rules limit the size of the deficit – or so they think.

So “deficit doves” think deficits are fine as long as you wind them back over the cycle (and offset them with surpluses to average out to zero) and keep the public debt-GDP ratio in line with the ratio of the real interest rate to output growth. Torturous formulas are provided to students on all of this under the presumption that the government faces a financing constraint and as long as it is cautious things will be fine.

The CEPR has in recent days proposed employment policies which clearly indicate it doesn’t understand how the currency works. I intend to analyse these in a separate blog sometime soon.

But the point here is that under fixed exchange rates, a current account deficit was problematic and limited by the accumulation of foreign reserves (particularly US dollars) that a country had. Chronic CAD countries were always faced with domestic contraction to take the pressure of their currency and allow the central bank to maintain the fixed parity.

The political fallout that CAD nations had to deal with was one of the reasons the Bretton Woods system collapsed (finally) in 1971. For example, in the 1960s, Britain was faced with stagnation if it held its Sterling parity with the USD. A large nation like this carried clout and its subsequent “competitive devaluations” placed the fixed exchange rate system into jeopardy … and ultimate collapse.

Further, under flexible exchange rate system, any country which is running a CAD is according to modern monetary theory (MMT) “financing” the desires of foreigners to accumulate financial assets (or other assets) in the currency of issue. That is the reason that the foreigners are willing the ship more real goods and services to the country than the latter has to ship back to the foreigners.

So a CAD in any country with flexible exchange rates, are positive for welfare because exports impose costs and imports provide benefits to the nation in question.

It is true that the foreigners may reduce their desire to hold financial assets in the currency of that nation, in which case its trade account is forced to adjust. There is no doubt that a sharp and sudden adjustment can be hard on welfare levels.

It is also true that a lot of countries are bullied into contracting in foreign currencies which then cause it problems if their export revenue declines. The IMF in particular forces developing countries to contract in foreign currencies. This is madness and exposes the country to the risk of insolvency should it run short of foreign currency reserves. MMT tells us that a nation should never contract in foreign currencies if it wants to to preserve the zero risk of insolvency that a sovereign currency bestows on a government.

Finally, as Argentina has demonstrated – a nation that runs out of foreign reserves can default on its foreign currency obligations without long-term problems. Normally, a nation running a flexible exchange rate will not be forced into this position.

As an aside, Argentina’s problems arose from the fact that it was running a currency board where the peso was pegged against the USD. It was madness to enter into such an agreement in the first place given it was sovereign in its own currency. As soon as it entered that agreement (in 1991) it lost sovereignty and was headed for the ultimate collapse that occurred in late 2001.

It is interesting to consider the case of Latvia which has entered an IMF loan agreement during the current crisis. The CEPR Report says:

In the case of Latvia, for example, the pro-cyclical policies have been part of an effort to preserve a pegged exchange rate. This is similar to IMF-supported policy in Argentina during their steep recession of 1998-2002, where a fixed, overvalued exchange rate was supported with tens of billions of dollars of loans until it inevitably collapsed. In cases such as Argentina and Latvia, maintaining the peg means that adjustment must take place through shrinking the economy and real wage declines. Latvia’s GDP is projected to shrink by 18 percent this year.

So Latvia should first abandon the peg and then default on any loans that the government cannot pay or renegotiate them in the local currency – the Lat.

So this obsession of the IMF with stifling current account deficits in developing countries and forcing export-led growth is without a firm foundation in MMT. It reflects the inapplicable notions that mainstream economics uses to analyse economic behaviour. The same precepts that have led to this financial and real economic collapse.

The CEPR Report says:

The purpose of IMF lending during a world recession should be – as much as possible – to provide sufficient reserves so that borrowing countries can pursue the expansionary macroeconomic policies that high-income countries are capable of, in order to minimize the loss of employment and output, as well as more permanent or long-lasting damage that sometimes occurs in the most vulnerable countries.

Again, they are displaying their neo-liberal bias – that governments in developing countries like high-income countries have to borrow to spend in their own currency. Of-course, they do not. They can buy whatever is for offer in their own currency including all the idle labour. Not to many impoverished workers in developing countries will demand USD before they will offer an hour’s work!

What is pro-cyclical policy?

The CEPR Report considered fiscal policy to be pro-cyclical if there was a “a programmed reduction in the fiscal deficit (or an increase in the fiscal surplus) during a recession or significant growth slowdown” and monetary policy to be pro-cyclical if there was “an increase in policy interest rates during a recession or significant growth slowdown” or an explicit “tightening of monetary policy” (via constrained “reserve money growth”).

The following table is taken from Table 1 of the CEPR Report.

The IMF has a long-history of damaging the poorest nations. The so-called structural adjustment programs (SAPs) entered the scene in the late 1970s with the debt crisis that engulfed the world. This was constructed as a crisis for the developing nations but it was really a crisis for the first-world banks. The IMF made sure the poorest nations continued to transfer resources to the richest under these SAPs.

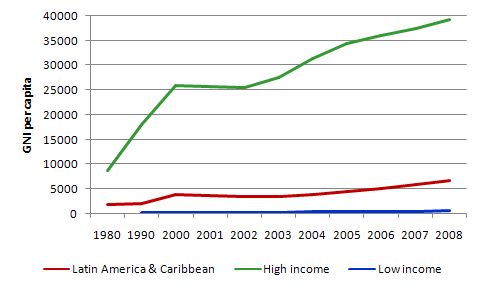

The overwhelming evidence is that these programs increase poverty and hardship rather than the other way around. The following graph comes from the World Development Indicators, provided by the World Bank. It shows Gross National Income per capita, which, in material terms is an indicator of increasing welfare.

Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa (which dominates the low income countries) were the regions that bore the brunt of the IMF SAPs since the 1980s.

While the high income countries enjoyed strong per capita income growth over the period shown (since 1980), Latin America (and the Caribbean) has experienced modest growth and the low income countries actually became poorer between 1980 and 2006.

The two trends are not unrelated. The SAPs are responsible for transferring income from resource wealth from low income to high income countries.

There are many mechanisms through which the SAPs have increased poverty. First, fiscal austerity is almost always targetted at cutting welfare services to the poor – which often means health and education (the IMF claims that educational and health cuts no longer happen). But moreover, the cuts prevent sovereign governments from building public infrastructure and directly creating public employment.

Second, public assets are typically privatised. Foreign investors often benefit signicantly by taking ownership of the valuable resources.

Third, contractionary monetary policy forces interest rates up which often discriminate against women who survive running small businesses.

Fourth, export-led growth strategies transform rural sectors which traditionally provided enough food for subsistance consumption. Smaller land holdings are concentrated into larger cash crop plantations or farms aimed at penetrating foreign markets. When international markets are over-supplied, the IMF then steps in with further loans. But the original fabric of the land use is lost and food poverty increases.

Fifth, user pays regimes are typically imposed which increases costs of health care, education, power, and in some notable cases, reticulated clean water. Many of the poorest cohorts are prevented from using resources once user pays is introduced.

Sixth, trade liberalisation involves reductions in tariffs and capital controls. Often the elimination of protection reduces employment levels in exporting industries. Further, in some parts of the world child labour becomes exploited so as to remain “competitive”.

I could go on about this at length. I haven’t touched on the way the IMF loans help private firms (often large multinationals like BP, ExxonMobil and others) undermine the natural environment in poor countries.

Anyway, next week I am off to Kazakhstan on an Asian Development Bank mission and I will be providing advice to various Central Asian governments. I will be telling them to float their exchange rates, cut their interest rates, and expand fiscal policy to provide employment guarantees and skills development.

I will report each day while away as to how things are going! The IMF have been visiting this region a lot in the last year or so and so I expect to meet a lot of resistance to different ideas. But things are not working out for these countries and they have tried 15 or more years of market liberalisation and IMF-style remedies to no avail. They realise it is time to do things better. MMT has the answers to help them do that.

Neo-liberal abuse of children

The Washington D.C.-based Employment Policies Institute (EPI) has launched what it calls a “high-profile, multi-million dollar ad campaign highlighting the threat posed by unsustainable borrowing and spending.”

They have a television campaign where young children in a classroom recite the so-called Pledge of Allegiance

I pledge allegiance to America’s debt and to the Chinese government that lends us money. And to the interest for which we pay compoundable with higher taxes and lower pay until the day we die.

Mike Norman (friend of MMT) has the video of the child abuse here. I would rather link to him rather than the original site so they don’t get deluded that 10,000 more hits have come their way.

In the press release the EPI said:

… This campaign is all about getting people to understand the frightening reality of the massive federal debt … People do not realize just how much 12 trillion dollars is, and what it will take for our country to get out from under that level of debt. Americans also aren’t aware of how much money we now owe to foreign governments and just how unsustainable our current level of spending is. We have to do something to defeat the debt now, or we will live to regret it.

You cannot get more manic than that. 12 trillion dollars = 12 trillion dollars. If that is the public debt so what? What is the unemployment rate? What is the GDP growth rate? What is the state of inner-city housing? The education system? The health system? These are the things that will determine America’s future not the debt level.

Hello Mr. Mitchell,

Last August I was researching sustainable debt levels and came across your website. I was intrigued and have followed your blog closely ever since. As a result I am currently auditing a course with Marc Lavoie and am very interested in your functional finance approach coupled with the insights into our fiat monetary system. Unfortunately I was unfamiliar with functional finance despite having received a graduate degree (Masters) in economics from McGill University in 1987.

In any event my question to you involves Cuba. I recently spent a month there and for the first time travelled around various parts of the country, speaking to people and learning Spanish. Previously I had only gone to beach resorts. It is a very odd place – two exchangeable currencies, vast undersupply of consumption goods, but good basic services (health, education, daycare) freely available. It is also safe to walk around at night even in poor areas. I went into peoples’ homes and was surprised at the level of poverty many of them live in. Understandably there is considerable frustation about that.

I was wondering if you know of a serious economic evaluation of Cuba’s economy with proposals for improvements. It seems to me that the use of MMT should be useful although the output levels of so many things there are so low I suppose they would hit the inflationary ceiling of maximum output in pretty short order.

Thanks for your blog. I am impressed by the level of time and energy you devote to it. I appreciate it very much.

Keith Newman

Gatineau, Quebec

Canada

You have a fascinating blog.

But don’t you think that China’s fixed exchange rate has helped its economic growth?

Surely the fact that it had capital controls and a fixed exchange rate prevented it from experiencing the East Asian economic crisis?

Also, what it your view of capital controls?

Don’t you think they are necessary to control de-stabilizing flows of “hot money”?

In a system where countries have free floating exchange rates and a liberalized capital account, monetizing government deficit spending will just lead to massive capital flight and a collapse in the exchange rate (possibly even hyperinflation as the cost of imports surges).

How does a country using neo-chartalist methods of government spending overcome this problem?

If you a creating money from nothing for government spending and running a current account deficit, where do you get the foreign exchange for purchasing the energy, raw materials and manufactured goods you need to import?

Just a quick comment on Cuba as well, following from Keith Newman’s remarks.

One major reason where Cuba is so poor is the United States Embargo against Cuba, which has existed since 1960. This has surely been a massive cause of economic stagnation in Cuba.

In a previous post (“D for debt bomb; D for drivel …”), you describe the pre-1982 Australian system of issuing government bonds called the “tap system”:

bond issues were made using the “tap system”, whereby the government would announce some volume of debt it wanted to issue at a particular rate and then sell whatever was demanded at that yield. Occasionally, given other rates of return in the financial markets the issue would not be fully subscribed – meaning some of the Government’s net spending would be covered in an accounting sense by central bank buying treasury bills (government lending to itself!).

My question is: how often before 1982 did the Australian central bank monetize government debt under this system?

Are “tap systems” of this kind still used by other governments?

Where would I get more information on this system (in the academic literature)?

Dear Keith

Thanks for your introductory comment and welcome. Marc is very solid in his understanding of modern monetary theory although we might has slight differences of viewpoint in terms of policy design. We also had a nice joke a few years ago together. We were sitting on a bus together going up to the Abbey of Montecassino (in Cassino, Italy) as a tour during a conference. The road was very steep and there were no safety rails and the bus was full of Post Keynesian economists. I cannot recall who said it but at one point when the bus seemed to lurch near to the edge either Marc or I said “News report – 90 per cent of the World’s progressive economists killed in a bus crash” – we laughed a lot and reflected on our minority status in the profession.

The main issue with Cuba, in my view, which Andrew noted, is the US trade blockade. After the Soviet Union collapsed Cuba’s markets collapsed. The Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (old soviet trading bloc) represented about 85 percent of Cuban trade and transactions were made in non-convertible currency. Between 1989 and 1993, trade with the Soviet Union fell by around 90 per cent and dried up with other Eastern European countries. There was a huge drop of imports which had provided inputs into Cuban industry (machinery, parts, raw materials etc). Farming supplies also fell by over 70 per cent.

MMT tells us that Cuba can employ all its people but if no-one wants to accumulate financial assets in Cuban currency then it will not be able to run current account deficits. So its living standards are largely determined by what it can produce and grow internally. That explains the scarcity of goods and services.

Inflation is low there (although some would say there is repressed inflation driven by scarcity).

Anyway, I am no expert of Cuba but I love the old son music (although I realise it was developed by the pre-revolutionaries and represents ruling class tastes).

best wishes

bill

Dear Andrew

Thanks for your comments.

Fixed exchange rate systems do not punish a country with huge net export surpluses and plenty of foreign reserves. But clearly they are in the minority.

First, I would eliminate via my banking reforms a great deal of the current “hot money” transactions. Please read Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks for more explanation.

Second, governments should only ever transact in the local non-convertible currency. With limited scope to transact in purely speculative assets, foreign investors who wish to profit in a country have to invest in physical (productive) capital. That cannot take flight. If the owners wish to abandon the country the assets remain.

Third, your statement about monetisation makes several assumptions – and I think you might read these blogs to clear a few things up. In a fiat monetary system the mainstream notion of monetisation is problematic.

Further why are you automatically assuming the mainstream logic – float, deficit, massive flight, collapse of parity, hyperinflation? Further if the exchange rate collapses why does the price of imports dominate the volume loss?

My feeling is that these things did not happen in Japan as it pushed its deficit and public debt to record levels in the 1990s – it experienced deflation and an appreciating exchange rate.

Further, if you are running a current account deficit – by definition of the accounting that accompanies it you are financing the foreign saving in your currency. If not, then you are not running a CAD.

best wishes

bill

Dear Andrew

I would have to go back into the records to answer your question about how often the market didn’t take the full issue (note I don’t use words like monetise). You can probably do that research yourself if you are interested. The answer is that the market at times didn’t take the full issue depending on the yields offered by the government.

Most governments would use auction systems now.

I would start looking back through the economic history literature relating to public finance for more information.

best wishes

bill

Re: Cuba

Isn’t Cuba as a country free to trade with every other country in the world besides the US? Has any other country imposed sanctions on them?

–Phil

Dear Phil

Yes, even the US allows some form of agricultural and medical goods trade with Cuba – FAS information.

The point is that they have had to dramatically change their export and import strategy since the collapse of the CMEA. But Canada, Mexico, Argentina, China among others are large traders.

best wishes

bill

“Where I see a budget surplus squeezing non-government liquidity and forcing the latter into increased indebtedness to keep the level of spending up and growth going and conclude that a crash is imminent”

Bill,

In this and other posts (most have been related to late 1990s Clinton surpluses in the US) you have suggested that the government surplus was the causative force in the non-government sector increasing debt in lieu of income. While I believe that this direction of causation may be true in some situations, I am unconvinced that the causation must always occur in this direction. Is this belief your opinion or a fundamental tenet of Modern Monetary Theory?

Looking specifically at the US in the late 1990s… My opinion in this case is that the domestic private sector, by choosing to both spend more than its income by increasing debt (due to belief in a “new economy” of ever rising prosperity, etc) and to “save” via asset appreciation rather than income was the primary force that drove the government into surplus (in part via higher income and therefore higher tax receipts). If the government had reacted by spending more (or reducing taxes) and swung to a deficit, could not the non government sector have just used the extra income to attempt even higher levels of spending, thereby driving up inflation to unacceptable levels? Could you please clarify whether this disagrees with MMT theory versus being a matter of opinion?

To me, the evidence appears to support my view of the direction of causation. Inflation was in the 2-3% range and rising [graph], other than a dip from 1997 to 1998 that coincided with the Asian Financial Crisis and a sharp fall in energy prices [graph]. Capacity utilization was high [graph] and labor force participation was at record levels [graph] and unemployment was falling from 5% to 4% [graph]. Real GDP was already growing at a fast pace of 4-5% [graph]. The current account deficit was growing so it’s also possible the foreign sector, rather than the domestic private sector, would have benefited from the government’s potential injection of extra income.

So in summary what is the evidence that a US government deficit in late 1990s would have maintained similar growth and spending but with less private debt, rather than adding new spending and accelerating inflation? FYI I do agree with the MMT accounting identity that an increasing non-government savings rate requires requires an increasing government deficit in order to avoid a contraction in GDP (at least ignoring debt effects), but if the government sector is supposed to react in that case to the will of the non government sector, why shouldn’t it also be reactive (rather than try to be a causative/preventative force) in the case of intentionally falling non-government savings rate?

Hi Bill

What’s the modern monetary theory take on neo-classical growth theory and ‘new growth theory’?

Have you blogged/written on this in the past?

Bill and Andrew:

Bill wrote: Fixed exchange rate systems do not punish a country with huge net export surpluses and plenty of foreign reserves. But clearly they are in the minority.

Very true on both counts, of course. Regarding the latter point, by definition, naturally. Regarding the former, getting to the point of having a huge net export surplus and large foreign reserve position may have been rather punishing to the population in the first place, as several nations have demonstrated.

Best,

Scott

“So in summary what is the evidence that a US government deficit in late 1990s would have maintained similar growth and spending but with less private debt, rather than adding new spending and accelerating inflation?”

I don’t know that there would have necessarily been accelerating inflation. And I think its less about what the late 90s would have looked like and more about 2000 – 2006.

Remember in the late 90s there was still positive savings rate in the US – albeit around 2% and declining. Household debt was around 75% of GDP in 2000, but accelerated after 2000, peaking at close to 100% GDP late 2006.

Increased government spending does not preclude increased private debt to the extent that people are willing to borrow and banks willing to lend. To the extent that government spending increases the public’s income (did not really happen with Bush’s tax cuts and military spending), some increase of consumption spending would have been paid via income instead of debt.

However, the increase in private debt was also due to a drastic relaxation of lending standards – encouraged by a lax regulatory environment and a “maturing” of debt securitization techniques – particularly sub-prime and mortgage debt. Bush did have a huge tax cut (unfortunately not payroll taxes) and increased government spending (Iraq, security), driving interest rates down.

While incomes showed some small increase in real terms, income inequality increased – essentially telling us that lower income groups had declining real incomes. Thank god (tongue-firmly-in-cheek) that the financial services industry developed sub-prime lending to such a sophisticated degree – otherwise what would have happened?

I think you can safely say the lack of standards and securitization increased the supply of debt, while the decrease in real income for most US consumers and lower interest rates increased debt demand.

Bill,

Sounds like a useful metaphor for your paper would be the bloodletting that medieval physicians routinely practiced, even though patients usually died horribly. Seems like the IMF is applying a similar “therapy” to developing nations.

I am a bit more cynical, There may be more to it than ignorance. As you point out, the result is resource depletion and the taking over of asset of assets by foreigners. Could this be just a coincidence, or is it part of the policy. Of course, the left sees it as premeditated.

The encouraging thing is that developing nations haven’t been as corrupted by neoliberal theory, so they may be more open to arguments that elude made-up minds in the West. Hopefully, your work will be able to make a difference.

Best regards,

tom

hbl: “In this and other posts (most have been related to late 1990s Clinton surpluses in the US) you have suggested that the government surplus was the causative force in the non-government sector increasing debt in lieu of income. While I believe that this direction of causation may be true in some situations, I am unconvinced that the causation must always occur in this direction.”

Let me try it. The problem with government surplus is that in a sense it contradicts the idea of growing economy which obviously means that this situation is unsustainable. If you say that surplus was driven “due to belief in a “new economy” of ever rising prosperity” then it was obviously a false assumption. So “ever rising prosperity” should have been controlled by the government by cooling some speculative demand for debt or providing extra supply of “speculative” assets. For example, government could have spend its surplus on building social housing and providing it at subsidized prices/rents. So social function is performed, extra supply is provided implying lower levels of speculation and all at the “cost” of surplus being eliminated.