Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – August 7, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Mainstream economists use the notion of “crowding out” to argue that public spending squeezes out private spending and results in a less efficient allocation of resources overall. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) denies that crowding out can occur.

The answer is False.

The normal presentation of the crowding out hypothesis which is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention is more accurately called “financial crowding out”.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory. Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

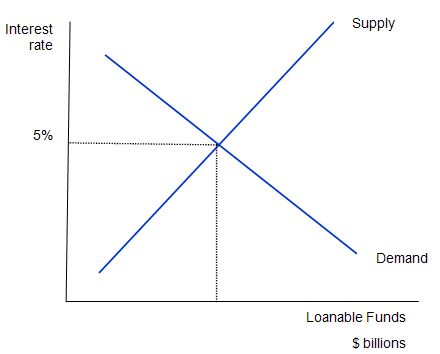

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment. Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that budget surpluses are akin to this. They are not even remotely like private saving. They actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of budget surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to “any other market in the economy” despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates – read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consquences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a budget deficit. Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

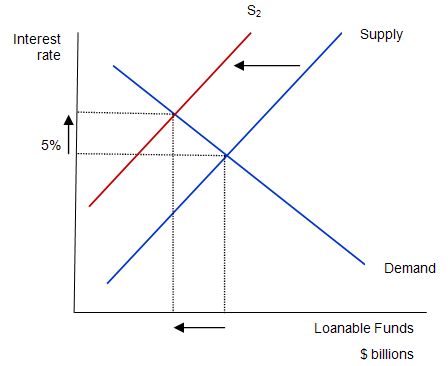

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2. Why does that happen? The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising budget deficit reduces public saving and available national saving. The budget deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Sometimes, this makes is hard to know where to start in debunking it. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no! Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors. Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading “financial crowding out”.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

However, other forms of crowding out are possible. In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

Further, while there is mounting hysteria about the problems the changing demographics will introduce to government budgets all the arguments presented are based upon spurious financial reasoning – that the government will not be able to afford to fund health programs (for example) and that taxes will have to rise to punitive levels to make provision possible but in doing so growth will be damaged.

However, MMT dismisses these “financial” arguments and instead emphasises the possibility of real problems – a lack of productivity growth; a lack of goods and services; environment impingements; etc.

Then the argument can be seen quite differently. The responses the mainstream are proposing (and introducing in some nations) which emphasise budget surpluses (as demonstrations of fiscal discipline) are shown by MMT to actually undermine the real capacity of the economy to address the actual future issues surrounding rising dependency ratios. So by cutting funding to education now or leaving people unemployed or underemployed now, governments reduce the future income generating potential and the likely provision of required goods and services in the future.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues. If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that. It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example). But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

Question 2:

It is impossible for all national governments to simultaneously run public surpluses without impairing real economic growth because it is likely that the private domestic sector in some countries will desire to save overall.

The answer is False.

The question has one true statement in it which if not considered in relation to the rationale for the true statement would lead one to answer True. But the rationale presented in the question is false and so the overall question is false.

The true statement is that “it is impossible for all governments (in all nations) to run public surpluses without impairing growth”. The false rationale then is that the reason the first statement is true is “because it is likely that the private domestic sector in some countries will desire to save overall”.

The question thus tests a knowledge of the sectoral balances and their interactions, the behavioural relationships that generate the flows which are summarised by decomposing the national accounts into these balances, and the constraints that is placed on the behaviour within the three sectors that is evident in the requirement that the balances must add up to zero as a matter of accounting.

Once again, here are the sectoral balances approach to the national accounts.

We can view the basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics in two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

So you might have been thinking that because the private domestic sector desired to save, then the government would have to be in deficit and hence the answer was true. But, of-course, the private domestic sector is only one part of the non-government sector – the other being the external sector.

Most countries currently run external deficits. This means that if the government sector is in surplus the private domestic sector has to be in deficit.

However, some countries have to run external surpluses if there is at least one country running an external deficit. That country can depending on the relative magnitudes of the external balance and private domestic balance, run a public surplus while maintaining strong economic growth. For example, Norway.

In this case an increasing desire to save by the private domestic sector in the face of fiscal drag coming from the budget surplus can be offset by a rising external surplus with growth unimpaired. So the decline in domestic spending is compensated for by a rise in net export income.

So it becomes obvious why the rationale is false and the overall answer to the question is false.

It is impossible for all governments (in all nations) to run public surpluses without impairing growth because not all nations can run external surpluses. For nations running external deficits (the majority), public surpluses have to be associated (given the underlying behaviour that generates these aggregates) with private domestic deficits.

These deficits can keep spending going for a time but the increasing indebtedness ultimately unwinds and households and firms (whoever is carrying the debt) start to reduce their spending growth to try to manage the debt exposure. The consequence is a widening spending gap which pushes the economy into recession and, ultimately, pushes the budget into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

So you can sustain economic growth with a private domestic surplus and government surplus if the external surplus is large enough. So a growth strategy can still be consistent with a public surplus. Clearly not every country can adopt this strategy given that the external positions net out to zero themselves across all trading nations. So for every external surplus recorded there has to be equal deficits spread across other nations.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

- Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 3:

A rising government deficit will always allow the private domestic sector to increase its saving in nominal terms.

The answer is False.

This answer should be read as a complement to the discussion in Question 2 as it also can be considered in terms of the sectoral balances.

If the external balance is zero (that is, net exports equal zero) the there is a one-to-one correspondence between the government balance and the private domestic sector balance such that, for example, a 2 per cent budget deficit must be associated with a 2 per cent private domestic sector balance surplus.

So in this circumstance the answer would be true.

But things get complicated when we introduce positive or negative external balances. Then a 2 per cent budget deficit might be associated with a 3 per cent external deficit and so the private domestic sector balance will be in deficit.

So the answer is only true if the budget deficit is larger (as a percent of GDP) than the external balance and growing faster.

Question 4:

If government net spending increases (rising budget deficit) then policy is becoming more expansionary shift and the only risk is that the nominal aggregate spending growth might exceed the real capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output.

The answer is False.

Again this question has two premises – a statement and a related consequence. In this case the statement that “If government net spending increases (rising budget deficit) then policy is becoming more expansionary” is false and the related consequence that “the only risk is that nominal aggregate spending growth might exceed the real capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output and cause inflation” is true.

Taken together the answer is false.

First, it is clearly central to the concept of fiscal sustainability that governments attempt to manage aggregate demand so that nominal growth in spending is consistent with the ability of the economy to respond to it in real terms. So full employment and price stability are connected goals and MMT demonstrates how a government can achieve both with some help from a buffer stock of jobs (the Job Guarantee).

Second, the statement that a “If government net spending increases (rising budget deficit) then policy is becoming more expansionary” is exploring the issue of decomposing the observed budget balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the budget process.

The federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 5:

Assume the government increases spending by $100 billion in the each of the next three years from now. Economists estimate the spending multiplier to be 1.5 and the impact is immediate and exhausted in each year. They also estimate the tax multiplier (which captures the impact of rising tax rates on GDP) to be equal to 1 and the current average tax rate is equal to 30 per cent. What is the cumulative impact of this fiscal expansion on GDP after three years?

(a) $135 billion

(b) $150 billion

(c) $315 billion

(d) $450 billion

The answer was $450 billion.

In Year 1, government spending rises by $100 billion, which leads to a total increase in GDP of $150 billion via the spending multiplier. The multiplier process is explained in the following way. Government spending, say, on some equipment or construction, leads to firms in those areas responding by increasing real output. In doing so they pay out extra wages and other payments which then provide the workers (consumers) with extra disposable income (once taxes are paid).

Higher consumption is thus induced by the initial injection of government spending. Some of the higher income is saved and some is lost to the local economy via import spending. So when the workers spend their higher wages (which for some might be the difference between no wage as an unemployed person and a positive wage), broadly throughout the economy, this stimulates further induced spending and so on, with each successive round of spending being smaller than the last because of the leakages to taxation, saving and imports.

Eventually, the process exhausts and the total rise in GDP is the “multiplied” effect of the initial government injection. In this question we adopt the simplifying (and unrealistic) assumption that all induced effects are exhausted within the same year. In reality, multiplier effects of a given injection usually are estimated to go beyond 4 quarters.

So this process goes on for 3 years so the $300 billion cumulative injection leads to a cumulative increase in GDP of $450 billion.

It is true that total tax revenue rises by $135 billion but this is just an automatic stabiliser effect. There was no change in the tax structure (that is, tax rates) posited in the question.

That means that the tax multiplier, whatever value it might have been, is irrelevant to this example.

Some might have decided to subtract the $135 billion from the $450 billion to get answer (c) on the presumption that there was a tax effect. But the automatic stabiliser effect of the tax system is already built into the expenditure multiplier.

Some might have just computed $135 billion and said (a). Clearly, not correct.

Some might have thought it was a total injection of $100 billion and multiplied that by 1.5 to get answer (b). Clearly, not correct.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

OMG !!! Has anyone else seen the Wikipedia entry for “Quantitative Easing”?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantitative_easing

Dear Bill,

I believe that there could be an issue with the questions 2 and 4

I read these questions as logical implications not logical conjunctions.

If we make a false initial proposition but the implied proposition is true, the whole sentence is true.

SOURCE_http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truth_table

I know that this is counter-intuitive but this is how implication has been defined. Otherwise we would need to say “if and only if” and we would have logical equality. Or to say (proposition1 AND proposition2) which was possibly your intention – to have a conjunction.

Bill, you contradict yourself in Q4. You say “So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes” which means the answer to Q4 is maybe because we can not conclude that “If government net spending increases (rising budget deficit) then policy is becoming more expansionary” without additional information. It might be expansionary and it might not.

Since you asked for any comments, especially if you’ve made an error. I think I’ve spotted one. You’re entire approach and the entire body of your theory is fundamentally flawed because you ignore political constraints.

KD