I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Spending multipliers

Several readers have E-mailed about the concept of a multiplier in macroeconomics particularly in light of comments I made yesterday about the current debate as to whether the deficits will be expansionary and whether it would be better to cut taxes rather than increase spending. There appears to be a lot of confusion about the most basic concepts involved so this blog seeks to address some of those issues. It is not a comprehensive literature review.

Multiplier theory

Students begin to learn about the expenditure multiplier in a very simple model without government or external sector. It sets them up immediately to disregard the crucial relationship between government and non-government sector that really drives the dynamics of the monetary system.

In the text book that Randy Wray and I are currently working on the government/non-government relationship is introduced at the beginning of the learning process to ensure students understand the importance of net positions etc.

So I don’t think it is too hard to explain the expenditure multiplier with government spending, taxes and imports introduced from the start.

The clue is to first of all realise that aggregate demand drives output with generates incomes (via payments to the productive inputs). I won’t go into controversies here about whether the productive inputs are rewarded fairly or whether surplus value is expropriated etc. That is a separate and not unimportant discussion but not germane here to understand the accounting and the dynamics.

Accordingly, what is spent will generate income in that period which is available for use. The uses are further consumption; paying taxes and/or buying imports. We consider imports as a separate category (even though they reflect consumption, investment and government spending decisions) because they constitute spending which does not recycle back into the production process. They are thus considered to be “leakages” from the expenditure system.

So if for every dollar produced and paid out as income, if the economy imports around 20 cents in the dollar, then only 80 cents is available within the system for spending in subsequent periods excluding taxation considerations.

However there are two other “leakages” which arise from domestic sources – saving and taxation. Take taxation first. When income is produced, the households end up with less than they are paid out in gross terms because the government levies a tax. So the income concept available for subsequent spending is called disposable income (Yd).

To keep it simple, imagine a proportional tax of 20 cents in the dollar is levied, so if $100 of income is generated, $20 goes to taxation and Yd is $80 (what is left). So taxation (T) is a “leakage” from the expenditure system in the same way as imports are.

Finally consider saving. Consumers make decisions to spend a proportion of their disposable income. The amount of each dollar they spent at the margin (that is, how much of every extra dollar to they consume) is called the marginal propensity to consume. If that is 0.80 then they spent 80 cents in every dollar of disposable income.

So if total disposable income is $80 (after taxation of 20 cents in the dollar is collected) then consumption (C) will be 0.80 times $80 which is $64 and saving will be the residual – $26. Saving (S) is also a “leakage” from the expenditure system.

It is easy to see that for every $100 produced, the income that is generated and distributed results in $64 in consumption and $36 in leakages which do not cycle back into spending.

For income to remain at $100 in the next period the $36 has to be made up by what economists call “injections” which in these sorts of models comprise the sum of investment (I), government spending (G) and exports (X). The injections are seen as coming from “outside” the output-income generating process (they are called exogenous or autonomous expenditure variables).

Investment is dependent on expectations of future revenue and costs of borrowing. Government spending is clearly a reflection of policy choices available to government. Exports are determined by world incomes and real exchange rates etc.

For GDP to be stable injections have to equal leakages (this can be converted into growth terms to the same effect). The national accounting statements that we have discussed previous such that the government deficit (surplus) equals $-for-$ the non-government surplus (deficit) and those that decompose the non-government sector in the external and private domestic sectors is derived from these relationships.

So imagine there is a certain level of income being produced – its value is immaterial. Imagine that the central bank sees no inflation risk and so interest rates are stable as are exchange rates (these simplifications are to to eliminate unnecessary complexity).

The question then is: what would happen if government increased spending by, say, $100? This is the terrain of the multiplier. If aggregate demand increases drive higher output and income increases then the question is by how much?

The spending multiplier is defined as the change in real income that results from a dollar change in exogenous aggregate demand (so one of G, I or X). We could complicate this by having autonomous consumption as well but the principle is not altered.

Consumption and Saving

So the starting point is to define the consumption relationship. The most simple is a proportional relationship to disposable income (Yd). So we might write it as C = c*Yd – where little c is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) or the fraction of every dollar of disposable income consumed. We will use c = 0.8.

The * sign denotes multiplication. You can do this example in an spreadsheet if you like.

Taxes

Our tax relationship is already defined above – so T = tY. The little t is the marginal tax rate which in this case is the proportional rate (assume it is 0.2). Note here taxes are taken out of total income (Y) which then defines disposable income.

So Yd = (1-t) times Y or Yd = (1-0.2)*Y = 0.8*Y

Imports

If imports (M) are 20 per cent of total income (Y) then the relationship is M = m*Y where little m is the marginal propensity to import or the economy will increase imports by 20 cents for every real GDP dollar produced.

Multiplier

If you understand all that then the explanation of the multiplier follows logically. Imagine that government spending went up by $100 and the change in real national income is $179. Then the multiplier is the ratio (denoted k) of the Change in Total Income to the Change in government spending.

Thus k = $179/$100 = 1.79.

This says that for every dollar the government spends total real GDP will rise by $1.79 after taking into account the leakages from taxation, saving and imports.

When we conduct this thought experiment we are assuming the other autonomous expenditure components (I and X) are unchanged.

But the important point is to understand why the process generates a multiplier value of 1.79.

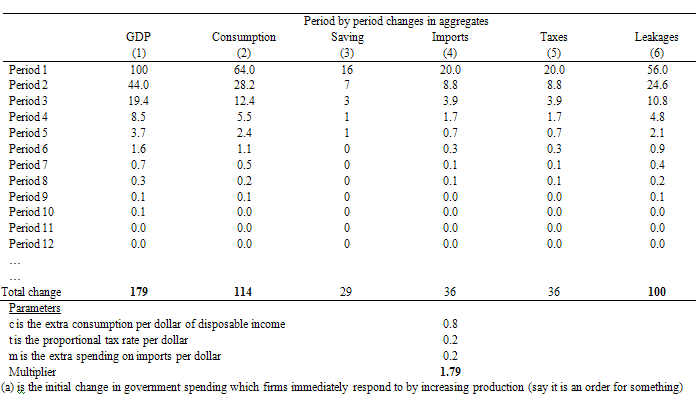

Here is a spreadsheet table I produced as a basis of the explanation. You might want to click it and then print it off if you are having trouble following the period by period flows. If anyone wants the spreadsheet I will E-mail it. If too many want it I will put a link to it.

So at the start of Period 1, the government increases spending by $100. The Table then traces out the changes that occur in the macroeconomic aggregates that follow this increase in spending (and “injection” of $100). The total change in real GDP (Column 1) will then tell us the multiplier value (although there is a simple formula that can compute it). The parameters which drive the individual flows are shown at the bottom of the table.

Note I have left out the full period adjustment – only showing up to Period 12. After that the adjustments are tiny until they peter out to zero.

Firms initially react to the $100 order from government at the beginning of the process of change. They increase output (assuming no change in inventories) and generate an extra $100 in income as a consequence which is the 100 change in GDP in Column [1].

The government taxes this income increase at 20 cents in the dollar (t = 0.20) and so disposable income only rises by $80 (Column 5).

There is a saying that one person’s income is another person’s expenditure and so the more the latter spends the more the former will receive and spend in turn – repeating the process.

Households spend 80 cents of every disposable dollar they receive which means that consumption rises by $64 in response to the rise in production/income. Households also save $16 of disposable income as a residual.

Imports also rise by $20 given that every dollar of GDP leads to a 20 cents increase imports (by assumption here) and this spending is lost from the spending stream in the next period.

So the initial rise in government spending has induced new consumption spending of $64. The workers who earned that income spend it and the production system responds. But remember $20 was lost from the spending stream so the second period spending increase is $44. Firms react and generate and extra $44 to meet the increase in aggregate demand.

And so the process continues with each period seeing a smaller and smaller induced spending effect (via consumption) because the leakages are draining the spending that gets recycled into increased production.

Eventually the process stops and income reaches its new “equilibrium” level in response to the step-increase of $100 in government spending. Note I haven’t show the total process in the Table and the final totals are the actual final totals.

If you check the total change in leakages (S + T + M) in Column (6) you see they equal $100 which matches the initial injection of government spending. The rule is that the multiplier process ends when the sum of the change in leakages matches the initial injection which started the process off.

You can also see that the initial injection of government spending ($100) stimulates an eventual rise in GDP of $179 (hence the multiplier of 1.79) and consumption has risen by 114, Saving by 29 and Imports by 36.

In this case the change in the budget position would be (100-36) = $64 which has allowed private saving to rise. The implied current account deficit (with X fixed) would have increased a bit. A full model would introduce exchange rate effects. In this case, the exchange rate would likely fall a little (under the assumption of no change in autonomous X) which would stimulate X and reduce M a bit which would “crowd in” further income growth.

Further, inasmuch some imported inflation occurred (a tiny amount if any) then real interest rates would rise and might further stimulate output via investment. These additional effects are possible but probably fairly small in magnitude.

In general, the multiplier is larger the smaller the leakages. So the lower is the import leakage per dollar and the lower the taxation rate the larger the multiplier and the

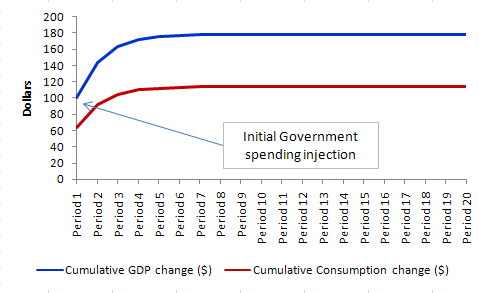

The following graph shows you the income and induced consumption adjustment path. The initial injection stimulates a lot of activity which then induces further consumption but in smaller and smaller amounts as the leakages impact in each period.

This type of approach also tells you that if the government was to cut taxes such that the households received the equivalent of $100 in extra disposable income the final multiplier would be lower because households will initially seek to save a proportion of the initial bonus. In other words, the first round injection would be less than the $100 and then the subsequent multiplier rounds would be smaller and the process would exhaust itself more quickly.

The current controversy

In January 2009, Christina Romer and Jared Bernstein released a working paper as part of the new US President’s fiscal strategy entitled – The Job Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Program.

They are the Chief economists of the US President and US Vice-President respectively.

In their Appendix 1 (page 12 onwards) you see how they derived their multipliers. They say that:

For the output effects of the recovery package, we started by averaging the multipliers for increases in government spending and tax cuts from a leading private forecasting firm and the Federal Reserve’s FRB/US model. The two sets of multipliers are similar and are broadly in line with other estimates. We considered multipliers for the case where the federal funds rate remains constant, rather than the usual case where the Federal Reserve raises the funds rate in response to fiscal expansion, on the grounds that the funds rate is likely to be at or near its lower bound of zero for the foreseeable future.

Earlier they suggest that the private forecasting model Macroeconomic Advisers, which you can learn about HERE

They then model the output (income) effects of a permanent stimulus of 1 per cent of GDP (percent) using either a public spending injection and/or an equivalent tax cut (equal to 1 per cent of GDP). The two multipliers estimated were 1.55 for government spending and 0.98 for tax cuts, which are consistent with the usual approach.

So if government spending increases by 1 per cent of GDP the total increase in GDP is 1.55 per cent after 16 periods of adjustment. They then used these estimates to further estimate the number of jobs the US stimulus package would generate.

Paul Krugman commented on the Report in January soon after it was released and said that:

… the estimates appear to be very close to what I’ve been getting.

The key thing if you want to do comparisons is to note that I made estimates of the average effect over 2009-2010, while they do estimates of effect in the fourth quarter of 2010, which is roughly when the plan is estimated to have its maximum effect. So they say the plan would lower unemployment by about 2 percentage points, I said 1.7, but their estimate may actually be a bit more pessimistic than mine. They have the plan raising GDP by 3.7 percent, but that’s at peak; I thought 2.5 percent or so average over 2 years, again not much difference.

Anyway. the multipliers that Romer and Bernstein used are fairly standard even though the way they used the FRB/US model was to suit the current situation as I note below.

In September 2009, the ECB released a working paper – New Keynesian versus Old Keynesian Government Spending Multipliers – which was written by noted anti-fiscal mainstreamers John F. Cogan (Stanford University), Tobias Cwik (Goethe University), John B. Taylor (Stanford University) and Volker Wieland (University of Frankfurt).

The ECB paper claims that by using a more robust but “typical current New-Keynesian model” they estimate “the likely GDP impact of the fiscal stimulus measures” to be “only 1/6 of the estimates presented by Romer and Bernstein”. In other words very small indeed.

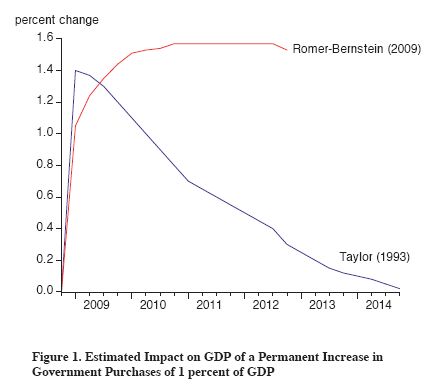

The disagreement is summarised by the following graph which is Figure 1 in the ECB paper, which (page 7) describes the Taylor (1993) model “is a rational expectations model with staggered wage and price setting and thus could be described as ‘new Keynesian'”. As they say in the classics, one of them cannot be correct.

The ECB paper (page 7) summarises the difference as:

Perhaps the most important difference is that in one case higher government spending keeps on adding to GDP “as far as the eye can see,” while in the other case the effect on GDP diminishes as non-government components are crowded out by government spending.

So you will already be anticipating what the debate will be about. It rests to no small degree on the extent to which financial crowding out occurs in money markets as a result of the stimulus package.

Attempting to gain the higher authority, the ECB paper uses the “Smets-Wouters model” which they claim is:

… representative of current thinking in macroeconomics. It was recently published in the American Economic Review and is one of the best known of the empirically-estimated “new Keynesian” models … The Smets-Wouters model was highlighted by Michael Woodford … as one of

the leading models in his review of the current consensus in macroeconomics.The term “new Keynesian” is used to indicate that the models have forward looking, or rational, expectations by individuals and firms, and some form of price rigidity, usually staggered price or wage setting. The term also is used to contrast these models with “old Keynesian” models without rational expectations of the kind used by Romer and Bernstein.

New Keynesian models are commonly taught in graduate schools because they capture how people’s expectations and microeconomic behaviour change over time in response to policy interventions and because they are empirically estimated and fit the data. They are therefore viewed as better for policy evaluation. In assessing the effect of government actions on the economy, it is important to take into account how households and firms adjust their spending decisions as their expectations of future government policy changes.

I will return to the status of New Keynesian models shortly. But their claim that Romer and Bernstein used “‘old Keynesian'” models without rational expectations” is patently false. The Federal Reserve FRB/US is hardly an “old fashioned” approach.

For those technically inclined you can read about its specification in this summary manual. Don’t waste your time if you are not interested in the macroeconometric structures of these sorts of models.

But if you read the document you soon learn that the notable developments of the FRB/US include:

… greater emphasis on modeling expectations, especially the assumption that expectations are rational or consistent with modeled outcomes; more extensive use of dynamic optimization theory to characterize responses of households and firms to shocks; expansion of the types of models in general use to include atheoretic vector autoregressions (VARs) and theoretically-based, general equilibrium models of business cycles; and development of new statistical techniques for estimation of long-run relationships among trending series and for testing facets of equation performance.

To readers not familiar with any of this jargon this description means that the structure of the model is, in fact, very modern in terms of the latest developments in the modelling literature and agents are assumed to have rational expecations.

To get to the point the model works more or less like this in the context of a government spending increase. Assuming the level of federal government purchases is increased permanently by 1 percent of GDP (as in the Romer and Bernstein experiment), the FRB/US model would normally predict an immediate increase in real GDP by 1 per cent as in the usual expenditure multiplier story.

However, because all agents (households and firms) in the economy have rational expectations (that is, on average they guess the future correctly), long-term interest rates rise which crowds out private spending and exports decline. This is the typical crowding out story in all mainstream models.

So not long after the rise in real income, the higher interest rates kill off the stimulus and the expenditure multiplier drops to zero.

However, as Federal Reserve Vice-Chairman Donald L. Kohn noted (Source):

… if financial market participants anticipate that the federal funds rate will remain at zero for an appreciable period of time following the hike in government spending, the simulated short-run fiscal multiplier rises to 1.3 for some time. Model simulations also indicate that the fiscal spending multiplier may rise even further – to around 2 – if the fiscal stimulus is expected to be temporary and to last no longer than the period when monetary policy holds short-term interest rates at the zero lower bound.

These impacts occur because the long-term interest rates are conditioned by the central bank’s target rate setting (the federal funds rate) and so there is no crowding out coming via that route. Further, if the stimulus is temporary, the perceived funding requirements of the deficits are seen to be temporary and the agents do not build in future squeezes occurring in capital markets.

This latter scenario is more or less what Romer and Bernstein assumed in their modelling (although they assumed the expenditure increase was permanent) which would reduces the multiplier below 2 and back towards 1.5.

Please note that the theoretical structure embedded in these models are pretty crazy and do not reflect the way the modern monetary system actually operates. But the point is that the ECB criticism of these models as somehow being old Keynesian approaches which have been superceded by the New Keynesian wizardry is completely without foundation.

So the ECB paper does not represent the alternative correctly.

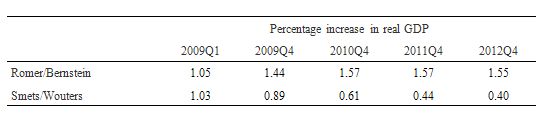

It is thus no surprise that they “cook” up a different outcome. The following Table is taken from ECB Table 1 (page 12) and shows the difference in simulations between the Romer and Bernstein modelling and the ECB modelling. How does the ECB explain the difference?

The ECB paper (page 12) conclude:

Our assumption is that, as of the first quarter of 2009, people expect the government spending increase to continue permanently (as in the Romer-Bernstein policy specification), and that the spending increase is initially debt financed. The Smets-Wouters model assumes that any increase in debt used to finance the increased government spending is paid off with interest by raising taxes in the future. We assume that these taxes are “lump sum” in the sense that they not affect incentives to work, save or invest. They do, however, lower future after tax earnings and thereby wealth. If we took such incentive effects into account the increase in government spending would eventually reduce real GDP. Hence, our assumptions err on the side of overestimating the size of the impact of government spending on real GDP.

The main driver of the small multiplier (in some simulations they claim there is a negative multiplier – that is, government spending destroys income) is the forward-looking households and firms who are changing their expectations and behaviour in direct response to new fiscal policy initiatives. In this case, it is claimed that all agents know that a penny today is a penny gone tomorrow in higher taxation.

Accordingly, when higher government spending and debt is observed people realise they will have to pay it all back with higher taxes in the future. So households immediately state consuming less today to save to pay the higher taxes. The negative wealth effect is very strong by construction in the Smets and Wouters model

So it all comes about because there is an intertemporal government budget constraint assumed and the government has to pay back the borrowing via higher taxation which impinges on household wealth and they cut consumption.

But there is also crowding out assumed via the higher interest rates caused by the debt issuance. Hence, later on you read (page 17) that:

In the Smets-Wouters model there is also a strong crowding out of investment. Hence, both consumption and investment decline as a share of GDP in the first year according to the Smets-Wouters model. This negative effect is offset, as shown in Figure 1, by the increase in government spending in the first year, but it causes the multiplier to be below one right from the start.

So government spending is assumed to drive up interest rates by competing for scarce saving and this squeezes out investment spending.

How might we assess these New Keynesian models? While, I do not usually agree with former Financial Times blogger Willem Buiter but earlier this year (March 3, 2009) in this article – The unfortunate uselessness of most ‘state of the art’ academic monetary economics – I found myself totally concurring with his insight.

Buiter was commenting on the “state of art” models in mainstream economics, particularly so-called rational expectations approaches which morphed into the New Keynesian models. He concluded:

Most mainstream macroeconomic theoretical innovations since the 1970s (the New Classical rational expectations revolution associated with such names as Robert E. Lucas Jr., Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, Robert Barro etc, and the New Keynesian theorizing of Michael Woodford and many others) have turned out to be self-referential, inward-looking distractions at best. Research tended to be motivated by the internal logic, intellectual sunk capital and esthetic puzzles of established research programmes rather than by a powerful desire to understand how the economy works – let alone how the economy works during times of stress and financial instability. So the economics profession was caught unprepared when the crisis struck.

For further in-depth analysis of New Keynesian models please read my blog – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time – for more discussion on the futility of these models.

To drive the point home further that these sorts of models have no real world applicability nor use to designing policy, Buiter noted that (emphasis in the original):

The most influential New Classical and New Keynesian theorists all worked in what economists call a ‘complete markets paradigm’. In a world where there are markets for contingent claims trading that span all possible states of nature (all possible contingencies and outcomes), and in which intertemporal budget constraints are always satisfied by assumption, default, bankruptcy and insolvency are impossible. As a result, illiquidity – both funding illiquidity and market illiquidity – are also impossible, unless the guilt-ridden economic theorist imposes some unnatural (given the structure of the models he is working with), arbitrary friction(s), that made something called ‘money’ more liquid than everything else, but for no good reason. The irony of modeling liquidity by imposing money as a constraint on trade was lost on the profession.

Both the New Classical and New Keynesian complete markets macroeconomic theories not only did not allow questions about insolvency and illiquidity to be answered. They did not allow such questions to be asked.

So they are principally exercises in counting the angels dancing on pinheads. That is, useless for determining policy outcomes in a modern monetary economy. In the event that they do have any policy implications they are asserted by theoretical imposition – so government spending always drives up interest rates and if interest rates didn’t rise then inflation would occur.

All the major results are assumed from the start and the econometric estimation procedure is “cooked” to get the structure of the model that is required to satisfy the underlying ideological preferences. Garbage in, garbage out! Please read my blog – GIGO – for more discussion on this point.

Buiter is again worthwhile on this point:

In both the New Classical and New Keynesian approaches to monetary theory (and to aggregative macroeconomics in general), the strongest version of the efficient markets hypothesis (EMH) was maintained. This is the hypothesis that asset prices aggregate and fully reflect all relevant fundamental information, and thus provide the proper signals for resource allocation. Even during the seventies, eighties, nineties and noughties before 2007, the manifest failure of the EMH in many key asset markets was obvious to virtually all those whose cognitive abilities had not been warped by a modern Anglo-American Ph.D. eduction.

Conclusion

I am not seeking to defend Romer and Bernstein here. But their estimates of the multiplier are reasonable of what is likely to happen. The way they derived them is questionable but that is another point.

It is highly unlikely that the Federal Reserve will hike interest rates in the coming year unless there is a very strong rebound in US GDP growth.

The attacks on them by Taylor and crew using New Keynesian models that are strong on conservative ideology but weak on just about every else are not worth considering.

The theoretical structure of these New Keynesian models bear no relation to how a modern monetary system operates. The assumptions about agents being forward-looking is reasonable but to think that a households predict future government policy with zero mean errors and adapt their behaviour on the basis of their predictions is far-fetched.

It is much more likely that households and investors notice the stimulus that government spending has provided and gather confidence that recovery is starting and redefine their spending decisions based on that renewed hope.

There is no empirical basis for assuming that tax rises will automatically follow government spending increases. Sometimes they do, sometimes they do not. It all depends on the circumstances and how much spare capacity there is in the economy.

It is highly unlikely that households are saving right now and withdrawing from consumption in order to pay for some tax rises in the years to come. The evidence from Australia is very clear – households are starting to spend again even though the public deficit has risen substantially as a percentage of GDP.

Hi Bill,

Maybe its worth stressing that the “equilibrium” is a short-run equilibrium and the saving leakage is not exactly a leakage – once it is reached, stock-flow consistent consumption functions – i.e., inclusion of consumption out of accumulated wealth adds an equally interesting story and we have a further multiplying effect while the government keeps injecting and taxing.

I have a boatload of questions to you Billy:

All variables used in this model are observable. How well do past data fit this model? Did someone took the time?

What would happen to the multiplier, if we add the constraint of a constant goverment debt/GDP ratio? (constraint on t)

I have a bit the feeling of sitting in a bus with two steering wheels. There seems to be missing a very important aspect in this model – monetary policy.

When confronted with the problem of understanding a complex system, it often helps me taking the systems model ad-adsurdum – see if your model behaves “reasonably” in the extremes. Make it fit “asymptotically”.

///////////////////////////////

Gedanken-experiment No 1:

///////////////////////////////

What happens if all the newly issued government debt is bought only by banks on margin? Assumptions: yield curve is steep, banks are allowed to leveage 1:999 – money supply is very very elastic.

The dynamics:

Central bank prints == buys short term debt => CBs balance sheet grows + keeps yield curve steep => makes the banker’s life easy – “borrow short term, lend long term” => demand for all “risk-free” securities along the yield curve grows => government spends newly printed money borrowed at artificially low interest rates => continues until output gap shrinks sufficiently so that inflation kicks in => nominal prices, income, wages grow => default risk and thus interest rates drop for private sector which from now on takes over.

Ordinary people have access only to their savings (and a thinny bit of leverage), but banks and government have access to an infinite pool of “savings” safeguarded only by the central bank.

Would in this case a crowding out effect occur? What is the spending multiplier in this model?

////////////////////////////////

Gedanken-experiment No 2:

///////////////////////////////

Now lets take the problem another time ad-adsurdum, but this time to another extreme:

“Helicopter Bernanke” became “Loan-shark Bernanke” => Nobody wants to borrow from CB => CBs balance sheet is empty => CB defacto disappeared from the market => We are on a quasi gold standard. Money supply is totally unelastic. Islamic banking has conquered the world – no more leverage. All issued government debt must be financed with “real” existing savings. Would in this case a crowding out effect occur? What is the spending multiplier in this model?

/////////////////////////////////

Another puzzling question… Which private investors do you economists actually mean to be “crowded out” by excessive government spending to fight deflation?

Do economists speak about those poor investors, who want to borrow, but cant, because in this deflationary environment their default risk adjusted interest rate does not cover the ROI of their investments?

Or do they speak about those other poor investors, to whom this whole situation just looks too creepy, so they dont even want to borrow?

the problem is that a higher multiplier means ‘more bang for the buck’

however that misses the point when govt. spending is not constrained by revenues, and taxes function to regulate demand and not to collect revenue per se.

so if a particular tax cut, desired by the electorate, for example, and needed to support aggregate demand, happens to have a low multiplier, all the better!

That means taxes can be cut even more to sustain demand at desired levels.

Same with a spending initiative.

Probably a dumb question, but how does debt figure in the income analysis above?

Debt repayments are presumably considered to be “saving”. Is money borrowed from banks considered to be “income”?

Hi Gordon,

Taking the liberty of answering on Bill’s behalf – any error is purely mine – Bill is never wrong (-:

This is just an illustration in a simplified economy to illustrate the concept of a multiplier.

Government debt/GDP ratio is an endogenous number outside the control of the government.

Monetary policy transmission for increasing aggregate demand is at best weak. Higher coupon payment due to higher interest rates (in the past) can improve aggregate demand.

Compare other blog posts here and you have a great explantion of what is going on in Japan.

Good for the banks if they buy all the debt. Unlikely though. There are households, corporates, mutual funds, and the rest of the world too!

Central banks don’t print for buying debt. They print if the commercial banks require currency to satisfy the daily needs of customers. They buy government bonds by increasing bank reserves. Borrow short term, lend long term is an out of paradigm view of how banks work. However government spending and less taxing increases aggregate demand because each dollar of deficit adds a dollar to the private sector. This improves their balance sheets and in the present scenario they may continue to save till the point they are comfortable with their balance sheeets and then start increasing their spending. It is the government which can achieve an increase in aggegate demand not the central bank.

Governments never “have” money or no money.

There is no crowding out. It is based on a model of the world which has a finite/constant volume of money.

Sure! Any scenario:

Too hypothetical. There are no helicopter drops. Ever seen one ? Any youtube links ? In normal circumstances only banks borrow from the CB. In these circumstances, central banks are playing the role of the lender of the last resort. CBs can’t force anyone to borrow. Government debt is not financed. It just looks like it is financed. Government spends first and then taxes.

Crowding out is a myth.

Yes – you can see a lot of posts here where the urgency of improving demand and employment is spoken about.

Mainstream economists think that the central bank sets the bank reserves and thus the money supply and the story is over. However Bill works for CofFEE – Center of Full Employment and Equity. His research has been developing the modern monetary theory and about convincing other economists and policy makers about the incapability of the private sector to provide full employment even in “good times”.

Back to multipliers. This post was just a simple illustration of the concept of multiplier and if you look at Warren’s comment above, its just an abstract concept and open to all kinds of misinterpretation. Have a bit of patience and read to read the posts in the Debriefing 101 category because mainstream economics is full of misconceptions, myths and religious indoctrination. Going back to gold standard, which many economists seem to argue – can be very dangerous.

Hi Bill and friends,

Why are imports taken leaked Y and not Yd? Can’t saved money be invested? Why is investment a injection? What evidence do you have that deficit spending will lower exchange rates?

Cheers!

Contrary to popular opinion, helicopter drops are fiscal operations, since they change net financial assets of the non-government sector. Every fiscal operation does this, while no monetary operations do this.

Tschaeff:

1. Imports can be leaked Yd if you want, just another step mathematically ,but not hard.

2. You seem to be confusing investment in capital with investment in financial assets. Investment here refers to the former, not the latter, whereas your questions appear to assume the opposite. Clearly investment in capital is an injection, as any domestic spending is, but investment in financial assets is just as clearly not in and of itself. At any rate, your question about saved “money” (I don’t like to use that term . . . I’ll assume you are referring to bank liabilities) begs the questions “how was the money created?” As a liability on the banking system’s balance sheet, it can only be created by an increase in bank assets (e.g., loans) or an increase in the qty of vertical “money” (which creates bank assets (reserves) and liabilities simultanously).

3. Regarding deficits and lower exchange rates, that’s the neoclassical view. We see it as much more complex than that and there’s no necessary relationship . . . exchange rates can go down due to a deficit (rising imports via rising domestic spending) or up (int’l investors desire to increase net saving in domestic currency as deficits strengthen the economy).

Best,

Scott

Scott,

Thank you for responding. I must have not asked the question right, and it certainly had typos 🙁 Let me try again. Bill wrote, “The injections [I,G,X] are seen as coming from “outside” the output-income generating process (they are called exogenous or autonomous expenditure variables).” Investment – Confuses me. How is it different than Consumption? In your reply you say “investment in capital is an injection, as any domestic spending is” So by that logic shouldn’t C be in injection too?

As for private savings being used for investment, isn’t that a horizontal relationship? People transfer after tax income (in the form of bank liabilities) to a business which uses it to invest in capital?

Off topic but couldn’t increasing taxes also increase the exchange rate, since it would give people a need to hold onto the local currency rather than exchange it? A problem a lot of small countries have is that any money they have they convert it on the exchange markets for dollars or euros. But that money doesn’t go away after it is exchanged, it’s just held in different hands, but the exchange rate drops, i guess? I’d love it if you guys would make a post (refer a link?) about exchange rate effects.

Bill must be assuming C is driven by income or disposable income (haven’t read the post all the way). Usually it’s assumed C has an income-driven component and an non-income-driven component; must’ve left out the latter, but it’s really not material overall. The part of C that’s income driven is endogenous, obviously, not exogenous. Only the exogenous parts are “injections,” by definition.

Regarding saving/investment . . . the point is, where did the saving come from? It’s like when reserve balances are transferred to the govt to pay taxes . . . where did the reserve balances come from? Further, just as the deficit creates net saving for the non-govt sector, the investment spending creates saving for the non-govt sector.

Exchange rates are complex. Yes, increasing taxes can raise exchange rates. It can also reduce them. Depends on many things. I can’t recall anything definitive on this, actually, but maybe someone else does.

Best,

Scott

“further, just as the deficit creates net saving for the non-govt sector, the investment spending creates saving for the non-govt sector.”

To illustrate what you’re saying: Investment = Private Saving + (Government Revenues – Government Spending) + (Imports – Exports)

Forgive me, I’m still missing something important. What would happen if a government deficit was run, and no business decided to invest in capital, consumers saved everything, there are no taxes, no ROW, the multiplier is 0. Now private savings have increased by the amount of the government deficit, but investment is left unchanged. I thought Savings and Investment all are part of the Non-Government Financial Balance. Another source of confusion is talking about investment as capital, physical things, and savings being numbers in some spreadsheet.

Dear Tschäff

Yes in this case G = S. So GDP = G (in a simple model where there is no exogenous C) and therefore all government spending would be saved by the private sector. But that doesn’t make your second statement inaccurate.

They do represent the components of the private balance (one leakage and one injection) which in your very strange example means that (I – S ) < 0 and so the private sector saves all its income.

And the multiplier would be 1 not 0 because there is no "induced consumption spending" (MPC = 0) to generate second and further round spending effects. The multiplier is 1/[1 -c(1-t) + m] where c is the MPC, t is the tax rate and m is the marginal propensity to import. So if c = 0 (households save all income) and t = 0 and m = 0 then the multiplier = 1 /[1 – 0(1-0) + 0] = 1/1. So an additional $1 in Government spending will generate an additional $1 in GDP.

In this type of model all these things are real dollar flows (or whatever currency unit you are dealing with). Saving is a dollar flow (that is so many $ per period) as is investment. The point that was being made by Scott is that in these sorts of macroeconomic models saving is done by households and investment is done by firms and comprises increases in productive capacity. The point then is that they reflect decision-making by two different economic groups (with different motivations) and so there is no reason to think they will be coordinated in any way. What brings the leakages and injections together are income adjustments (via imports, taxation and saving changes).

hope that helps

best wishes

bill

Dear Tschäff and Scott

I was using the most simple consumption function C = cYd so no exogenous consumption is involved. Including this would just scale the expenditure plane upwards (vertically) by whatever the assumed exogenous C was. To understand the multiplier all the action is in the slopes of the functions – that is the MPC, the tax rate and the marginal import propensity. The slopes (or elasticities) or propensities – whatever you call them – tell you how the leakages respond to changing income driven by an initial injection of spending from “outside” the system – that is, government spending in this case.

The point about exchange rates is empirical ultimately and there are adjustment processes to consider – so it might depreciate in the short term then appreciate. But what is the point of concern anyway. I would probably say that a growing economy driven by domestic demand will see a rising current account deficit and a depreciating exchange rate (somewhat). If the source of growth is exogenous – say in Australia’s case at present – commodity prices – then growth will be accompanied by a rising exchange rate driven through the capital account.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Ok, I get how investment is an injection, and the MPC was 0 not multiplier, careless mistake on my part, your writeup in this blog was perfectly clear (to me) in this regard.

I’m trying hard to wrap my head around income equilibrating saving and investment.

” What brings the leakages and injections together are income adjustments (via imports, taxation and saving changes).”

so ex post savings=investment?

As you have explained investment is a decision made by firms based on future revenue and costs of borrowing. Firms may not decide to invest, but savers may choose to save. So how does savings = investment? Real vs. nominal? ex post vs ex ante?

Sorry to revive such an old comments thread but i ‘m a bit puzzled by the fact that you include imports in the GDP. Imports are an income leakage but they are also a GDP leakage. So i think that the correct final GDP data for your example is 179 – 36 = 143$ and the multiplier becomes 1,43. I would be happy to be wrong though 🙂

Kostas,

Imports (from the previous period) are removed from every period’s generated GDP. Specifically, GDP(t) = Consumption(t-1) – Imports(t-1), excluding Period 1. So the total change doesn’t include imports, for them being a leakage as you mention. In fact, the total change can be seen as 100 (initial spending generates equal income) + 114 (income generated by consumption, derived after removing taxation and saving) – 36 (Imports) = 179.

would , at 1.55 multiplier for govt. spending, govt. have to spend $2.1T in order to increase gdp by $1.12T which would be enough to hire 28 million people at an average $40k each? govt. would have to spend that much each yr. to achieve their reemployment? thanks!