Last Friday (December 5, 2025), I filmed an extended discussion with my Kyoto University colleague,…

British currency gyrations are about weak government not fiscal deficits

The British government has descended into high farce. It is rather embarassing to watch adults behave in the way they have conducted themselves in the last longtime. I also note that the usual suspects are out in force claiming (spuriously) that the economic turmoil that has beset Britain demonstrates categorically that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is deeply flawed and the real world is now teaching us that we should be discarded into the dustbin of history – or rather disgrace. These characters, which include so-called progressives think that hard core fiscal rules, like the British Labour Party took into the last election would have saved the day for Britain. I guess they are now mates with the IMF, who in their latest fiscal monitor – Fiscal Monitor – overnight (published October 12, 2022) – called for fiscal restraint. Also, central bankers who met in Washington over the last few days decided they had become the elected and accountable government making gratuitous threats that if fiscal policy wasn’t turned to austerity, they would punish citizens with further interest rate hikes. It is actually hard to find anything of sense in the current economic debate. It is despairing really.

First the Tweeters were Tweeting anti-MMT stuff again over the last few days.

One Tweet, from a former advisor to the Shadow British Chancellor in Corbyn’s Opposition, who seems obsessed with slighting MMT whenever he gets the chance (to reduce his own insecurity no doubt) said:

… You can’t wish away global capitalism, or its national features, because British govt can issue its own currency – this is essence of MMT approaches, we’ve now seen their limits. A radical govt *in particular* needs clear rules and a transparent, well-understood plan.

This is one of many recent claims that the economic turmoil in the UK as well as the global inflationary pressures are evidence that MMT is nonsense.

Apparently, progressives still think that the global gamblers in the financial markets are all powerful and a currency-issuing government can only get away with policies that are ‘approved’ of by these amorphous greed merchants.

That view goes back to the 1970s and earlier and was the basis of the then Labour Chancellor, Dennis Healey lying to the British people about having to borrow from the IMF as a cover for his neoliberal desire to impose fiscal austerity on a nation as he and the Labour Party leadership became increasingly lured by the Monetarist doctrines of Milton Friedman.

It is a view that still dominates progressive politicians around the world – to the detriment of citizens who support them.

And this view is then extrapolated into an attack on MMT, because they misleading claim that MMT denies that private markets can cause economic chaos under certain conditions.

First, MMT doesn’t deny that fluctuations in market sentiment can cause bad outcomes for a nations and challenge government policy settings.

Speculators will form views of what they can get away with when determining whether to ‘test’ the veracity of government policy.

If they think the government resolve to maintain a particular position is weak, then they are far more likely to push currency and bond trades into areas that can lead to a sense of crisis.

They can defeat such a government stance if the government surrenders as we saw on Black Wednesday, September 16, 1992.

I wrote about that in this blog post among others – Options for Europe – Part 51 (March 24, 2014).

The problem then was that the British government had foolishly joined the ERM (a fixed exchange rate system with European nations) and the structural differences between the different nations meant that the system was unsustainable.

The financial markets surmised (correctly) that the system would eventually be unsustainable and Britain would have to leave and float.

They also guessed correctly that the British government would stubbornly try to stay in the ERM as a result of ideological biases within the top echelons of the Cabinet.

Germany was also causally implicated because the Bundesbank refused to help its currency partners through interest rate settings and foreign exchange market interventions.

So the currency was ripe for financial market trades (short selling) and ultimately as long as the Government tried to defend the indefensible (the fixed exchange rate membership of the ERM), these trades would be successful and the currency would fall significantly in value.

The currency stability ended when Britain left the ERM, which is what MMT would have predicted.

Then, the problem was the fixed exchange rate obsession, which was never sustainable and that vulnerability was exploited.

The problem now is somewhat different.

The commentators are claiming that the financial markets didn’t approve of the various fiscal policy changes that the new Prime Minister (is she still in that role!) and Chancellor paraded.

The policies were somewhat crazy in the context although the energy price subsidies were okay.

The mainstream commentariat attempt to say that the financial markets rebelled because they hate fiscal deficits and the Truss proposals were going to push the deficit out further.

But I don’t think that was the issue.

The main issue was that the financial markets sensed the division in the Tory Parliamentary Party and the criticism from all and sundry about the ‘fiscal deficit blowout’ including the terrible Labour Party leadership.

They guessed correctly that the political pressure would eventually cause more political chaos and reversals in policies.

They were right – the Chancellor is gone, the PM is in deep trouble, and the new Chancellor is a fiscal hawk about to introduce policies that favour the rich.

So if the financial markets consider that the government will not stand by its policies they will attack and a weak government will essentially ratify the speculative instability.

That doesn’t mean high fiscal deficits are the reason or that MMT is moribund.

I am fully aware of the ‘power’ of global financial capital.

But equally, I know that a resolute government can see of the financial market bids to undermine it.

I wrote about that last week in this blog post – Zero trading in 10-year Japanese government bonds signals Bank of Japan supremacy (October 13, 2022).

The financial markets tested the Japanese government, the Ministry of Finance which is planning even larger deficits and the Bank of Japan which is wedded to continue its yield curve control, which basically plays the investors out of yield determination.

The Japanese policy institutions stood firm, and the speculators were rendered benign (with losses).

A world away from the political chaos in Britain.

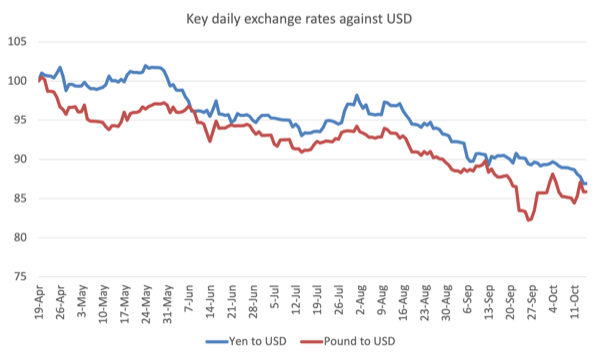

This graph shows the daily exchange rate movements (indexed to 100 on April 19, 2022) for the yen to USD and the pound to USD up to October 10, 2022.

You can see the recent fall in the value of the pound, which in the last week has been somewhat reversed.

Two points:

(a) Both currencies have depreciated against the USD mainly because of the aggressive relative interest rate increases introduced by the Federal Reserve Bank, which has shifted demand towards USD-denominated financial assets (and strengthened the currency).

That has nothing to do with the sustainability of the different fiscal policy decisions.

(b) If anything, the Japanese government’s monetary and policy stance is more offensive to mainstream views than the rather banal Truss mini-budget.

And around the same time that the UK mini-budget was being announced, the Japanese central bank governor reaffirmed its decision to maintain negative interest rates and yield curve control.

Further, the Japanese Prime Minister announced further rather significant fiscal support to ease the cost of living pressures arising from the inflation at present.

So why did the financial markets precipitously sell of the pound and not the yen?

The difference is in the quality of government and the assessment of the speculators on the nerve of the government.

A weak, deeply divided government was always going to swing. The Japanese government knows its capacities and holds its position.

Note also that the Bank of England demonstrated its power against the speculators irrespective of what was happening with the mini-budget reversals.

I wrote about that in this blog post – The last week in Britain demonstrates key MMT propositions (September 29, 2022).

The second related point concerns the claim that some sort of formal fiscal rule would have avoided the currency gyrations in Britain.

I met with his former boss, the MP John McDonnell (in his role as Shadow Chancellor) on October 11, 2018 in London.

I documented that meeting in this blog post – A summary of my meeting with John McDonnell in London (October 11, 2018).

I also wrote this blog post – The British Labour Fiscal Credibility rule – some further final comments (October 23, 2018) – which attempted to summarise the debate.

That post also documents many other posts in the succession of my critique of the fiscal rule concept as normally applied and specific analysis of the so-called British Labour Fiscal Credibility Rule.

The Tweeter was at that meeting with John McDonnell, in the role as his economic advisor. He ‘left’ that position soon after!

As history, regular readers will know that I pointed out in several blog posts that the fiscal rule that the Labour Party had adopted was not only neoliberal in framing but was also unworkable.

The ‘advisor’ and a range of Labour Party lackies who had helped create the ‘rule’ rejected that assessment.

As it turns out, in the lead up to the 2019 General Election in the UK, the Labour Party quietly altered the ‘rule’ and took out bits that I had suggested were contradictory and would lead to them failing to honour their commitments under the ‘rule’.

They couldn’t, of course, acknowledge their earlier mistakes nor apologise for the attacks on me personally and professionally.

Fine.

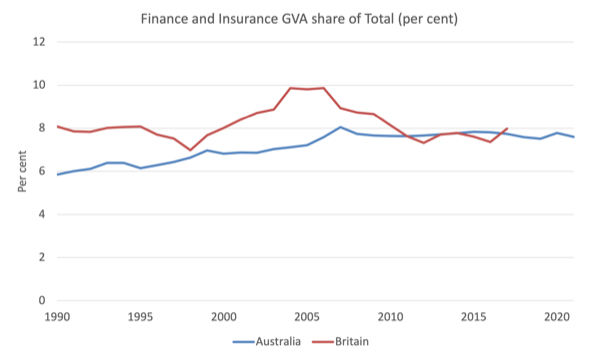

Underpinning the view that global financial markets can kill the British currency that the Labour Party was propagating, was the claim (at my meeting with John McDonnell) that the UK is a special case because its financial sector is so large relative to the size of the financial sector in other nations.

That specific claim was made by John McDonnell’s then advisor.

The inference was that the fiscal rule was necessary to placate any hostility that might arise in this ‘large’ sector.

I pointed out at that meeting that Australia was a small and very open economy with a significant financial sector as well.

There was disagreement about relative sizes.

Well is as it happens, Sydney and Melbourne are significant financial centres in the world markets.

The following graph gives you an idea of the relative size of the Finance and Insurance sectors in total Gross Value Added in Australia and the Britain.

In relative terms (to size of economy), the finance and insurance sector in the UK is broadly similar to the sector in Australia.

So I posed the question, given Australia has run current account deficits of around 3 to 4% of GDP since 1975 about, and fiscal deficits for much of that time, why hasn’t the finance sector rendered the Australian currency worthless?

The same goes for Japan. It is run large fiscal deficits, has significant public debt relative to its economic size, and has no problem selling more debt to the bond markets whenever it chooses.

Why hasn’t the Australian dollar been dumped given it ran large deficits in 2020 and 2021 and despite attempts to reduce it in 2022, it will remain relative large?

Why hasn’t the yen been dumped and made worthless by these financial markets?

I was told at that meeting that the difference is that the public debt is held by Japanese rather than foreigners and they are running current account surpluses.

So I pointed out the inconsistency.

Japan: current account surplus, debt held locally – no currency dumping.

Australia: typically in current account deficit, debt not held exclusively by locals – no currency dumping.

So all these arguments that somehow suggest the British financial markets are scarier than elsewhere fall by the wayside.

The difference that is palpable, especially recently, the quality of government and the certainty of policy.

The chronic uncertainty in Britain is the standout and that has nothing to do with MMT>

Further, governments abandoned formal fiscal rules mostly around 2020 when the pandemic changed everything.

Fiscal deficits rose variously around the world and government debt increased in line with the practice of issuing debt to accompany the rising deficits.

Why didn’t the financial markets sink currencies in 2020 and 2021 and earlier in 2022?

But think about the logic of the Tweet for a moment.

The latest Office of National Statistics (ONS) revealed that the British government fiscal deficit was £15.8 billion in the first-quarter 2022 which was equivalent to 2.6 per cent of GDP (Source).

In Quarter-2, 20220, the deficit was 27 per cent of GDP (£130.9 billion) as the fiscal support for the pandemic was substantial.

A year later, the fiscal deficit had dropped to 11.4 per cent of GDP (£65.4 billion).

The next three quarters, a significant drop was recorded.

Why didn’t financial markets attack the currency in 2020 or 2021, given that the fiscal position was so significantly at odds with previously stated ‘fiscal rules’ by the Government?

Perhaps the latest instability is nothing at all to do with the fiscal position?

The original ‘mini-budget’ was estimated intending to add £45 billion to the deficit position for tax cuts that would benefit the top-end-of-town.

That would have been about 2 per cent of GDP.

No-one credible believed the tax cuts would achieve the ‘growth’ outcomes claimed.

Further fiscal support of around £60 billion would be offered, some of it for good purposes.

The problem is that policy changes are rarely credible if there is a sudden shift of substantial proportions and size.

Given the circumstances, with supply chain issues and energy prices driving global inflation and demand running a little ahead of the constrained supply, the best thing the British government should have proposed was expanding fiscal support for the poorest British citizens and protecting low-income groups from the inflation.

That would have had a smaller impact on aggregate demand in a time when a rapid expansino in demand was unwise and would not have excited anyone.

MMt does not suggest there are zero fiscal consequences under all circumstances.

But also think about what the Tweeter was suggesting.

The implication is that the ‘absence’ of a fiscal rule provoked the financial markets to attack the pound.

So what sort of fiscal rule would have prevented such a reaction (thinking logically)?

The mainstream commentariat claims fiscal policy has to be supportive (read: subjugated) to monetary policy so as not to undermine the intent of the interest rate rises.

That means fiscal policy should be contractionary if that logic is valid.

This view, of course, doesn’t question the validity of the monetary policy stance, which from an MMT perspective is ridiculous at present given the inflationary drivers on the supply side.

But suspend that for a moment.

If the difference between financial market peace and all out attack is the absence of a fiscal rule, and that rule would have to be proposing austerity right now, given the mainstream logic and the circumstances, then we have a curious position where the progressive commentariat in the UK is advocating the smae position as the IMF.

It is not a position I support.

Conclusion

Same old bunk.

Let’s hope these views are expunged in some way from progressive politics.

Otherwise, there is not much difference between the two major sides in politics in our countries.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

That “there is not much difference between the major sides in politics in our countries” is the singular achievement of the neoliberal project whereby elected representatives abdicate their responsibilities for national economic outcomes and hand them over to the aristocratic institutions inimical to labour we call central banks.

In the UK this project was complete when Margaret Thatcher could proclaim that her greatest achievement was Tony Blair.

She wasn’t wrong …

There’s a pretty good quote in today’s papers

If we are to defeat the globalists, then we will need to oppose them properly. That does mean proposing shutting down the Gilt Market, defunding the IMF and sacking the MPC. Time to drive the money changers from the temple. Then if they complain it is because they want to defend their public sinecures with their overinflated incomes and colossal pensions, not because they have anything useful to say.

The Tories can’t do this because they are in thrall to the god of The Market(TM) and its false idol Confidence(TM). That is where the weakness stems from.

We can’t change these institutions. We have to replace them. No more pandering to the den of thieves.

But the real crux of the issue has been revealed after the narrative and framing changed over the weekend and as always it is Brexit and was Brexit’s fault.

One liberal after the other lined up and started to call for TINA and the reverse of Brexit. Most of the narrative and framing by so called left wing economists went like this.

“Macroeconomic populism is an approach to economics that emphasizes growth and income distribution and deemphasizes the risks of inflation and deficit finance, external constraints and the reaction of economic agents to aggressive non-market policies.”

With many adding So we need to reverse brexit. On Friday it was so obvious by the time the Sunday newspapers landed this is where the narrative and framing was heading.

The markets also hate strong trade unions, wealth redistribution, progressive taxation, financial regulation and countries that refuse to go along with US wars. Yet, the so called left wing economists in the UK emboldened in their timid TINA approach, so that attempts to reduce inequality & do anything genuinely progressive are sacrificed by them on the altar of fiscal discipline and hidden behind a fake fiscal sustainability narrative.

Who want

“Clear & predictable rules that fin markets can rely upon to continue to earn profits, plus a positive score from bureaucrats based on a neoclassical budget sustainability analysis, plus the thumbs up from the central banking class”

Basically, Remainers openly conceding that the EU/UK is run for the benefit of financial markets.

Of course MMT’rs have known this for a long time. Their masks always slip at the very first oppertunity. They just can’t help themselves as they protect their own GROUPTHINK and geopolitical view of the world.

Mainstream bourgeois economics which occupies a hegemonic position in the academic world today is often criticised for being “unreal”, This criticism though valid, does not capture its real intent, which is to serve as a means of camouflaging imperialism.

If you still don’t understand that then clearly you have not been paying enough attention.

Last August, Andrew Berkeley, Josh Ryan-Collins, Richard Tye, Asker Voldsgaard and Neil Wilson published a study entitled “The self-financing state: An institutional analysis of government expenditure, revenue collection and debt issuance operations in the United Kingdom.” (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/sites/bartlett_public_purpose/files/the_self-financing_state_an_institutional_analysis_of_government_expenditure_revenue_collection_and_debt_issuance_operations_in_the_united_kingdom.pdf) .

They claim to be the first detailed institutional analysis of the UK Government’s expenditure, revenue collection and debt issuance processes.

After analysing the interactions between HM Exchequer, the Bank Of England and commercial banks, they conclude that “(…) connect issuances (note: of newly created money) with ‘all the revenues to be received in the future’ (…) thereby framing expenditure implicitly as a form of credit advanced on the security of future tax revenues. This aligns with the chartalists theory of money described in Section 2, which asserts that fiat currency has value in exchange because of the sovereigns’s tax raising power (Innes 1914; Keynes 1930; Ingham 2004, Knapp [1905] 2013).”.

So, MMT has been around for quite some time.

It doesn’t fit the elite’s agenda, and so they always tried to push it away, and replace it with fairy tales, about the opposite, that you have first to collect revenue to fund expenditure.

Mainstream “economics” is a class war issue, a tale of lying, stealing and hoarding, sold as economics theory, which it isn’t.

The £ hasn’t recently been doing anything unusual relative to the euro which is the primary currency of the EU and which is still our main trading partner. So “gyrating” is a questionable term. Even at its recent monthly lowest it was still higher than it was during most of 2020 when the concern over the economic effects the Pandemic were at their height.

The problem, and the panic, has been over the £/$ exchange rate which always seems to command more attention than it probably should. So the complaint is that the dollar is higher than it should be rather than the pound and euro are too low.

Nevertheless, a good general always should choose the best time to engage the enemy. Truss and Kwarteng were naïve in the extreme by choosing the worst possible time. It’s difficult to side with either politically, however it clearly doesn’t make any sense to complain that the Government was unnecessarily raising taxes such as National Insurance in May and then complain it was planning to remove the increase in September. This is what much of the so-called progressive left ended up doing.

The reduction in the top rate of tax was probably neither here nor there economically. The rich, and their accountants, know very well how to avoid it in any case, but it was a huge blunder politically and has led to KK’s downfall and with Liz very possibly soon to follow.

Wouldn’t the change of price in government bonds be simple speculation on supply and demand rather than anything related to perceived government weakness?

Government announces “unfunded” spending, mechanically, according to their rules this means more bonds will be issued. Wouldn’t the astute trader simply anticipate a greater supply of bonds, compared to most likely an expectation of zero change in demand for the same bonds?

“Wouldn’t the change of price in government bonds be simple speculation on supply and demand rather than anything related to perceived government weakness?”

It tends to be speculation on the path of interest rates rather than the quantity.

The Gilt market is a small close knit setup with almost all action going via a small number of GEMMs (Gilt Edged Market Makers) that are usually part of a bank. They know very well that government spending hands them the money that will precisely match the amount of bonds the government finds it needs to sell. The trick then is to get as big a discount on those bonds from government as they can.

Remember bond issuing is a refinancing operation designed to drain excess reserves from the system that ended up there due to prior government spending.

@ Neil,

If Government spending ( or the difference between spending and taxation?) precisely matches the number of bonds the Govt needs to sell, what happens when the BoE to become involved as a buyer? They’ll be taking bonds out of the market to be replaced with cash and so lowering interest rates. This will mean the Government will eventually need to sell more bonds which could push the interest rate back up again.

@Peter Martin I think the answer to your question is to maintain the fiction that the BofE is independent of Government. So when the Treasury has sold bonds (maintain fiction of this being necessary to fill a funding gap), if the BofE subsequently buys some of those bonds, they are still outstanding as far as the Treasury is concerned, with interest to be paid to the BofE, and no need to be replaced.

QE notwithstanding, new Gilts are continuously issued by the Treasury as older ones mature.

To maintain the level of QE, the BoE also continues to purchase Gilts on the secondary market, as those that they already hold mature – even though the headline level of QE itself may not have been raised.

Technically speaking the BoE doesn’t buy Gilts. The asset purchase fund buys Gilts using a loan from the BoE.

The loan creates the bank reserves, and the APF purchases Gilts with those bank reserves and holds them to maturity. Or until it sells them back, whichever comes first.

Moving the Gilts up and down the money hierarchy doesn’t alter the arithmetic vis-a-vis the Debt Management Office.

@MrShigemitsu

“To maintain the level of QE, the BoE also continues to purchase Gilts on the secondary market”

The BoE quietly stopped doing this in February of this year. and they were planning to start QT, right up until Kwarteng’s budget announcement. Why the BoE would want to push up interest rates even more is a mystery to me, but then I am just an ordinary UK citizen, who dreams of living in a country run by adults.

Hi, how do the speculators gain from selling the pound when the Truss plans were announced? They are doing the selling and then when the policy is reversed they are doing the buying. If they sell shouldn’t they be hoping for continued decline in the pound? Much like 1992. How could the speculators have made a profit from this Truss situation? What benefit does the speculator get from pushing the currency into an area of perceived crisis and then buying it back on a reversal of policy? Couldn’t the speculators simply sell and buy regardless of government policy announcements, since they have the ability to move prices in particular directions.

Patient and methodical as ever, thanks Bill.

Bill,

I strongly disagree. Indeed I’ll go so far as to say you seem to be losing the plot!

I get that you’re more dovish on inflation than most economists, and (I think) I understand why. But there’s no reason for ignoring the theory you’ve developed! Many opponents of MMT misrepresent it as expansionary fiscal policy regardless of the circumstances, and you seem to be promoting their stereotype!

Not tightening fiscal policy now is as foolish as tightening it was last year.

There’s no point opposing the IMF for the sake of it – a stopped clock is right twice a day.

Indeed this is probably the first time in fifteen years that austerity is an appropriate policy response!

And though most of the inflationary drivers are on the supply side, making inflation difficult to control, that doesn’t mean the demand side should be ignored. And addressing it with tax increases would be less damaging than addressing it with interest rate rises.

Truss’s tax cuts were deeply irresponsible, and the situation would’ve been far worse had her government stuck to its guns. Speculators will generally lose money if they don’t take the position that the market’s heading for anyway.

Dear Aidan Stanger (at 2022/10/19 at 12:14 am)

Thanks for helping me understand my psychological state.

For the record, I did not suggest a large fiscal intervention was appropriate. But there is also no reason to go on an austerity path which is what the IMF is advocating.

That will just make the situation worse and when the supply factors ease, leave a mess to solve that was unnecessary to create.

best wishes

bill

“There’s no point opposing the IMF for the sake of it – a stopped clock is right twice a day.”

If the IMF said the UK couldn’t afford its fiscal policy, then the first thing to do is to stop paying the IMF and cash in the SDRs.

After all if we can’t afford our fiscal policy then we can’t afford to fund the IMF.

“And addressing it with tax increases would be less damaging than addressing it with interest rate rises.”

You forgot the third option. Just let the bottleneck inflation resolve itself. Remember that only monetarists and neoliberals really get upset by prices going up, because of their incorrect assumption about accelerating inflation. Keynesians just see the market reallocating scare resources until wage rises match price rises.

Don’t confuse bottleneck inflation with true inflation.

Hence the line: “1% of unemployment is more damaging than 1% of inflation”.

Japan inflation remains in check even as its currency weakens because Japan has already made the major adjustment of “living within its means”. It imports very little other than energy. And, has more than enough exports to offset these purchases.

The U.K. on the other hand imports a lot more than it exports, and has to run a trade deficit. So, a weakening currency has a much greater impact on the inflation the country experiences (until it also learns to live without the same level of imports it previously enjoyed as a byproduct of its exorbitant privilege, waning as it is).

This “loss” is not properly explained to the citizens of the U.K. and Europe, and that is why we see so much protesting in regards to the inflation people are experiencing.

MMT does not have a solution to ease this pain. No economic theory does.

The reason the economies of the developed world are managed the way they are is because the net gain from the exorbitant privilege the value of the country’s currency provides is significantly greater than the pain people people are incorrectly blaming on government policy. When the net gain vanishes, these economies will be managed in a way similar to what Japan is doing. Japan is just 20 years or so ahead of the curve (although this process is speeding up as China, and the rest of the developing world, put an end to the exorbitant privilege enjoyed by the developed world since the end of the gold standard, as the developing world also puts an end to the petrodollar.

This “loss” (having to pay more for imported goods) is the biggest hit that a country with the exorbitant privilege of being a printer of a currency that others (developing countries) will accept in return for actual goods and services (with the full knowledge, that when these IOUs are eventually cashed in, much of the purchasing power will have been inflated away) will have to absorb.

Developing countries accept this “trade off” as “the price” paid to develop.

This at least is my understanding. If I’m way off base, please let me know what I’m missing.

Sukh,

I’ll respond to some of your concerns. The answers you are looking for requires a full paradigm shift. Using the MMT lens and not constraining your ideas and solutions via the current economic paradigm.

The default position is that everybody buys with the currency they have and everybody sells for the currency they want to hold. The finance system then gets paid making those desires happen.If they don’t then no deal happens.

There is no need at all for smaller countries to borrow anything. The floating exchange rate will naturally find the level where the finance system can cause the funding to come about to make deals happen. Particularly as that will be driven by exporters with a surplus they need to get rid of somewhere.

To win at international trade you want to import as much as possible for as few exports as possible. Preferably the export that requires no labour to produce – the local currency.

” a weakening currency has a much greater impact on the inflation the country experiences ”

Is only looking at it from one point of view. The important thing to remember is that when a currency goes down, all the others in the world go up in relation to it and nations that rely upon exports (export led nations) start to lose trade – which depresses their own economy.

https://new-wayland.com/blog/its-the-exporters-stupid/

A current account deficit isn’t funded. For it to exist at all it must already have been funded. Every short has to have a corresponding long. Similarly for every excess import of goods and services into a currency zone there has to be a corresponding external sector held asset denominated in the currency of the import zone.

One cannot exist without the other. It is a simultaneous requirement in a floating system. If any step along the way fails the whole deal falls through, eliminating both sides instantly. Speculators that playing silly games laying on shorts in Sterling. They will do so until there is nobody is prepared to take the other side, no soft holders to panic out of their savings and no more flash crashes allowing dealers to close open long positions.

Then you will get the mother of all bear squeezes.

The game speculators play is to tempt the patsy of last resort - the central bank - into the speculation market to throw fresh salmon to the bears. A wise central bank will avoid doing this. Instead you would offer to clear needed trade flows with its reserves on a strict national policy basis - food and power and essentials: YES, Non essentials: luxury goods for example NO.

Then you offer refinancing to firms who have foreign currency loans, as long as they go through administration first so that the foreign currency loan is wiped out and the foreign bank is forced to take the loss.

Do everything to ensure the squeeze stays on track. Make your intentions known - there will be no liquidity for speculation outside the ‘natural’ supply. And that means, in an over-the-counter market of foreign exchange, liquidity may run out.

That is the responsibility of the other central bank with the high currency value and an excess export policy to decide what they want to do. They have to make the tough decisions along with their exporters if they want to keep their market share. Because we are not in a fixed FX environment as soon as they drop their prices the floating rate adjusts and makes your own currency stronger.

The problem is that central bank policy makers are still talking about shocks and equilibrium. They talk about pass through for exchange costs. But there seems to be little analysis of pass back (volume/price impact on the export side) because that would require acknowledging that the demand side matters - contrary to neoliberal dogma.

By keeping the mother of all bear squeezes in place and by making your intentions known.Speculators will think twice if they don’t want to sell the big issue outside of a train station. Those running the BOE today are part of the bank lobby. So would need to ask them why they throw more Salmon to bears when they need it. Why they do exactly what they want ?

Also the Only bonds the UK needs are Granny Binds

https://new-wayland.com/blog/the-only-bonds-we-need-are-granny-bonds/

Foreign holders of Sterling hold that money for neo-mercantile purposes due to a belief in ‘export-led growth’. They need to spend it, invest it properly, or be left, once again, with the default investment of a Sterling deposit in a bank. There is no reason why the UK voters should be propping up capital values in the Norwegian Global Pension Fund (or any other foreign pension fund or central bank) with public interest payments.

Finally you never mentioned the job guarentee the centre piece of MMT.

Ask yourself what happens to trade when you create full employment when To win at international trade you want to import as much as possible for as few exports as possible. Preferably the export that requires no labour to produce – the local currency. Think it through.

Also full employment encourages FDI which also works to make your own currency stronger.

I believe very large trade surpluses will become a thing of the past due to climate change. More countries will move to more war like economy and use diminishing real resources for themselves.

You just have to look at Russia under Sanctions for many years. It forced import substitution onto Russia. They became so good at it they export the surplus created from these reforms within their own borders.

This is sanctions we are talking about that made Russia stronger internally. So I don’t know why people freak out when a floating rate moves a few hundred basis points. It’s fixed exchange rate thinking creeping through the back door.

@ Sukre Hahre

‘It (Japan) imports very little other than energy.’

You sound like you’re saying this is a good thing and an example for the UK to follow. In previous times we’ve seen how trade restrictions and competitive mercantilism have led to trade wars which in turn have led to real wars. It is simply not possible for every country to export more than it imports. Japan runs close to balanced trade overall so maybe it isn’t quite as restrictive as you suggest?

You could perhaps have chosen Germany. This works sort-of-OK because there is only one Germany. It does depend on countries like the UK and USA running deficits so it can run its large surpluses. No-one is forcing anyone else in the world to send us more than we send to them in return. They can stop any time they like and balance their trade too.

You did ask what you were missing.

Dear Bill,

There is an interesting article on MAKROSOP from which I would like to quote:

“The following tweet from Simon Wren-Lewis, a former economic advisor to Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet, offers reason to critically examine the independence of “currency sovereign” states from financial markets as claimed by MMT:

“You can’t wish away global capitalism or its national characteristics because the British government can issue its own currency – that’s the essence of MMT, we’ve now seen its limitations.”” (end of quote)

And elsewhere in the article (Paul Steinhardt):

(quote) “In other words, representatives of finance capitalism have prevailed, no less committed like Truss to the neoliberal agenda of low taxes, deregulation and globalization, but unlike Truss also insisting on “sound fiscal policy” in the process.” (end of quote)

What’s your opinion on this?

Translated with http://www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Dear Helmut Hoeft (at 2022/11/02 at 2:59 am)

Thanks for the comment.

I think Makroskop lost its way a few years ago when they had all the internal conflict with key players. They now choose to perpetuate the fictions that the global investors are ultimately all powerful.

Quoting Wren-Lewis as an authority is an example of that.

The recent British experience was not about exposing the limitations of MMT but rather a demonstration of the inadequacy of a chaotic government.

If the financial markets are as Steinhardt claims so powerful, why haven’t they destroyed the yen?

I wrote about it here.

British currency gyrations are about weak government not fiscal deficits – https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=50622

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill

Thank you very much for your answer, I have a follow-up question:

Is it really just about the yen and Japanese economic policy? Is it not perhaps the case that the “financial sector” loves both: debt – from which it profits – and “sound” fiscal policy?