In an early blog post - Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy (October 15, 2009)…

Central bank priorities are not the priorities of working people

I remember a conversation I had when I was picked up hitch hiking to Melbourne from where I was living down the coast. It was during the 1970s inflationary period, which had morphed into stagflation as a result of deliberate government policy to create unemployment and discipline the wage-price spiral. The driver was a manual worker and during a conversation about the state of the economy (I was studying economics at the time) he said “the government should care about employment because at least then everyone has a job even if prices are rising”. That conversation stuck with me because it summed up what research shows in more sophisticated ways – the costs of inflation are minimal when compared to the devastating costs of unemployment. At present, our policy makers are unwilling to recognise that reality because it is not them that bear the costs.

Two events in the last week indicate that our policy makers have learned nothing in the 50 years since the last inflationary burst.

World Bank restates economic orthodoxy – no progress has been made

First, the World Bank released a paper late last week (September 15, 2022) – Is a Global Recession Imminent?.

The discussion indicates that there is now a “heightened … likelihood of a global recession in the near future”.

Why?

Because:

… many countries are withdrawing monetary and fiscal support. As a result, the global economy is in the midst of one of the most internationally synchronous episodes of monetary and fiscal policy tightening of the past five decades.

Then the orthodoxy sets in:

These policy actions are necessary to contain inflationary pressures, but their mutually compounding effects could produce larger impacts than intended, both in tightening financial conditions and in steepening the growth slowdown.

The World Bank thinks that:

1. “On the demand side, monetary policy must be employed consistently to restore, in a timely manner, price stability” – which means they believe the current inflationary surge (which is abating) is a over-spending problem (demand-side) rather than a supply-side problem.

So, according to that logic, central banks have to push up interest rates and squeeze borrowers, who then cut back spending as some go broke, which then creates unemployment and second-round, spending cuts as incomes vanish.

The logic doesn’t consider the alternative logic that the interest rate hikes drive up business costs and corporations with market power then pass the costs rises on and drive the inflationary surge.

In that latter scenario, and recognising that at present real wages are being cut quite dramatically in some nations (meaning wages are not pushing prices up), then we are not talking about some generalised wage-price spiral (as in the 1970s) but, rather, a massive real income grab by capital.

2. “Fiscal policy needs to prioritize medium-term debt sustainability while providing targeted support to vulnerable groups” – noting the emphasis on “prioritize”.

When we talk about public debt there is no analogue to what we might consider to be ‘sustainable’ in a private debt setting.

A sovereign government that issues its own currency can always meet its liability commitments and its central bank can always keep yields low.

Further, such a government doesn’t even need to issue debt instruments to match its net spending.

That is just a convention.

When an economist says that government must devote its main macroeconomic policy instrument to reducing its debt exposure they never ask the prior question – why is the debt being issued in the first place.

We know why it was issued under the Bretton Woods system – because otherwise, the central bank’s responsibility to manage currency liquidity to support the agreed exchange rate parities would be compromised.

But under the current system of flexible exchange rates (since 1971 in most nations), not such necessity exists.

And we know that the function of debt issuance is really to provide an elaborate form of corporate welfare (to provide a risk free asset they can park their speculative funds to reduce uncertainty).

The financial market lobby successfully pressured governments into maintaining debt issuance and then mounted a massive propaganda exercise to convince the rest of us that it was necessary because the government was like a big household and would run out of money otherwise.

We believed the propaganda and so it goes.

And in doing so, conservatives have a powerful political weapon to scare the public with so that governments have to ‘constrain’ their spending – at least when it relates to helping to reduce poverty and providing public services.

Very little constraint is exercised when it comes to supporting the military-industrial complex or bailing out private corporations in times of crises.

3. “On the supply-side, they need to put in place measures to ease the constraints that confront labor markets, energy markets, and trade networks” – which means the World Bank wants more deregulation and more freedom for corporations to do what they want to prioritise profits over general well-being.

It was this logic that has led to the rise of the gig economy, the loss of job quality and security, the flat wages growth, the massive spike in energy prices and falling service standards and all the rest of it.

It is the logic that has led us into this poly crisis and in no way represents part of the solution.

We should be looking into ways to take back control of the essential services like energy, telecommunications, water supply, transport etc to ensure they serve public interest rather than private profit.

The current supply problems are not due to excessive regulation but are most due to the fact that Covid has devastated workers in key part of the supply chain.

Embarking on policy that cuts employment and squeezes incomes of workers will just make that situation worse.

Australian RBA governor continues to lose the plot

Last Friday (September 16, 2022), the RBA governor and some of his senior staff made their annual appearance before the Federal House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics to present the central bank’s annual report for 2021.

As background, and I have written about this before, the RBA has been under fire from critics (including myself) for the way they have conducted policy over the last few years.

That criticism though is not uniform.

Most of the critics have been demanding rate hikes well before the Bank started the current hiking period.

I stand, of course, on the other side of that debate – highly critical of the interest rate rises in the face of mainly supply-side price pressures.

The governor Philip Lowe made a point last year of saying that interest rates would probably not rise until 2024 and only when wage pressures were obvious.

We have now had a series of interest rate rises despite the fact that the main wage data continues to show record low wages growth and massive real wage cuts.

The problem for the Bank is that many people, including low income earners, borrowed huge amounts of money to get into the housing market, on the promise from the Bank that rates would not rise any time soon.

So the accusation is that the Bank basically sucked in these borrowers to take out loans, many of which were on the brink of insolvency even at low rates, and those borrowers are now squeezed and many will lose their homes.

The Bank has also been criticised by mainstream economists for introducing their quantitative easing program, which purchased most of the debt issued as part of the fiscal support the Australian government introduced during the pandemic.

The claim is that the expansion was unwarranted and the pandemic was not as bad as first thought.

I disagree with those claims.

These issues framed the appearance of the Governor before the politicians at the House of Representatives Committe.

You can read the full transcript of the event in the – Official Hansard.

In the Governor’s opening statement he acknowledged that:

We are the banker to the Commonwealth government. We operate the official public account and are the government’s main transactional banker, providing banking services to the ATO, Services Australia and many government departments … We are also responsible for the core of Australia’s payment system, which allows money to move from one bank account to another.

We also print the nation’s banknotes.

So really an acknowledgement that the central bank is an instrinsic part of the federal government institutional structure.

But back to the point.

There was pushback from the Committee about the lure the RBA gave borrowers in 2020 and 2021 to borrow heavily on the assumption that rates would not rise until 2024.

The RBA has effectively admitted it made a mistake in making those predictions but appealed to the uncertainty of the situation at the time.

I won’t dwell on that issue.

But then the questions moved onto the monetary/fiscal policy coordination issue.

The Governor had earlier stated that the RBA was less concerned about the impact of the rising interest rates on household spending:

Partly it’s because the saving rate is still high, so people have the ability to smooth through the weaker growth in real income …

This is a familiar story.

Whether you think the saving rate is high or not depends on the perspective taken.

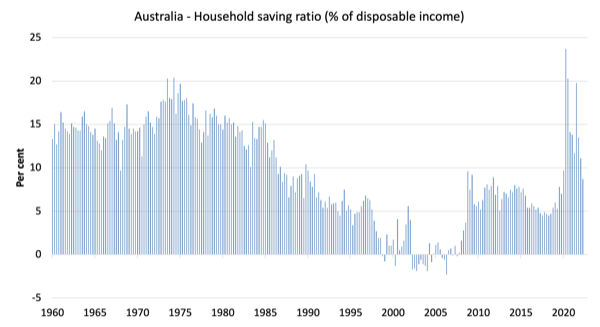

Here is the latest graph from the June-quarter National Accounts which I discussed in this blog post – Australian national accounts – wage share at record low while corporate profits boom – this is not right! (September 7, 2022).

It shows the household saving ratio (% of disposable income) from the June-quarter 1960 to the current period. See also the accompanying table.

We should acknowledge that Australian households currently hold record levels of debt – currently at 187.2 per cent of disposable income and rising.

Back in the full employment days, when governments supported the economy and jobs with continuous fiscal deficits (mostly), households saved significant proportions of their income.

In the neoliberal period, as credit has been rammed down their throats, the saving rate dropped (to negative levels in the lead-up to the GFC).

Hopefully, households are paying off the record levels of debt they are now carrying and improving their financial viability.

The following table shows the impact of the neoliberal era on household saving. These patterns are replicated around the world and expose our economies to the threat of financial crises much more than in pre-neoliberal decades.

The result for the current decade (2020-) is the average from March 2020.

| Decade | Average Household Saving Ratio (% of disposable income) |

| 1960s | 14.4 |

| 1970s | 16.2 |

| 1980s | 12.0 |

| 1990s | 5.1 |

| 2000s | 1.4 |

| 2010s | 6.4 |

| 2020- | 14.6 |

So I would not conclude that the household saving ratio is high.

In historical terms it is about average if we discount the credit binge period that basically led to the GFC.

Moreover, the idea that you squeeze households with higher interest rates and tighter fiscal policy and then hope they keep spending by running down their wealth is not only confused logic but also somewhat venal in intent.

It is confused because the justification for higher interest rates and fiscal austerity is to reduce demand relative to supply to bring down inflation.

But then they claim that households can keep spending by running down their savings.

It is also venal because they know that the higher interest rates fuel the profits of the banks and the wealth of the shareholders who spend less than the lower income workers, who are squeezed by the rate rises.

The RBA governor then made an extraordinary attack on the fiscal position of the government, proving that there is no independence and impartiality of the central bank.

He said:

My main observation on fiscal policy is really a medium-term one. There is significant issue there. At the moment, we’re the closest to full employment we’ve been in 50 years and we’ve got the highest terms of trade ever in Australian history, yet we’ve still got a budget deficit and are projected to have a budget deficit. That’s a significant issue …

Taxes, cutting back and structural reform-we have to do one of those three things, maybe all three of them, if we’re going to pay for the goods and services that the community wants from our governments.

The orthodoxy.

First, the unemployment rate is low for two reasons:

(a) the working age population growth stalled when the external borders were closed during the pandemic.

Migration numbers haven’t yet recovered and when they do the unemployment rate will rise from its current relative low levels.

My current estimate is that the true underlying rate is close to 6 per cent and with the business lobby pushing like mad and the government agreeing – migration numbers will soar in the next year or so.

(b) the fiscal support given to the economy was important and without it the unemployment rate would have soared well behind what actually happened.

So you have to ask yourself – if the current fiscal position supporting the current unemployment rate or is it superfluous?

My answer is obvious – if there is fiscal cuts then the unemployment rate will rise quickly.

Second, that means that the fiscal deficit is serving a functional purpose that advances well-being and trying to impose some ‘natural’ state of fiscal surplus will undermine that purpose.

Given the fact that the external position is unlikely to yield ever larger surpluses, the only way that we could continue to maintain GDP growth at the current levels and support the current unemployment rate with a smaller fiscal deficit would be if the private domestic sector increasingly goes into debt.

Which is the RBA governor’s ‘saving ratio’ argument.

He prefers a world where we rely on households and firms supporting growth through increasing debt and households running down their financial wealth while the public sector cuts services, investment in public infrastructure, hikes taxes and undermines job security tec.

That world has been tried over and over the last several decades and always leads to crisis.

It is unsustainable.

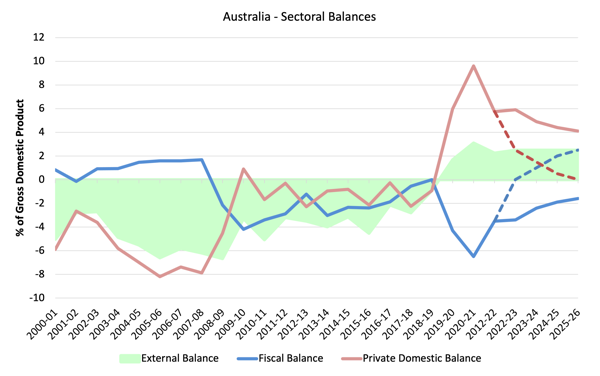

The following graph shows the sectoral balances for Australia from fiscal year 2000-01 to the end of the current forward estimates (2025-26). The black vertical line is when the forecast period in the current fiscal statement begin.

The hard lines are actual and projected.

You can see that given the current terms of trade boom in primary commodities, Australia moved from persistent current account deficit to a small surpluse in 2019-20 and is expected to continue in that state for a while yet (we will assume it lasts until 2025-26).

Should the terms of trade weaken as they will then the situation gets worse than I outline here.

You can see that the external sector situation and the strong fiscal support during the pandemic allowed the private domestic sector (households and firms) to increase its net financial surplus and as a sector stop the accumulation of debt for a time.

However, the fiscal cutbacks as the pandemic eased saw the net financial surplus in the private domestic sector fall.

The dotted lines are what would have happened had the government followed the ideas of the RBA governor and returned to surplus.

The private domestic surplus would vanish and the sector overall would start increasing its debt accumulation again.

But it is unlikely that scenario would play out like that.

What is more likely, and it relates to my point (b) above, is that the fiscal tightening towards a surplus would outpace the capacity of the private domestic sector to continue spending as their savings fell and interest rates rose and the economy would move into recession.

At that point, the fiscal position would remain in deficit as employment fell and tax receipts fell and welfare payments were forced to increased due to the increased number of unemployed.

So we would be left up with diminished private domestic wealth holdings, a ‘bad’ fiscal deficit (associated with higher unemployment rather than relatively low unemployment as is now), and then the terms of trade normalise – and then things get even more unattractive.

Conclusion

The Governor went on further about the ‘national credit card and about how if the government used fiscal policy to help people deal with the cost-of-living pressures that the RBA, itself, was making worse, then the RBA would probably have to hike rates even higher than they plan too.

His statement:

How far the government goes in that direction I don’t know, but I’m not concerned that there’s going to be some change in fiscal policy in the near term that’s going to make our job more difficult.

So think about that conversation I had a long time ago with the kind driver who picked me up hitchhiking when I was a student.

He had his priorities right – the priorities of working people.

Mr Lowe and his gang at the RBA have imposed a rogue set of priorities on the well-being of these people. The challenge is how to wrest power back of this gang.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Excellent post by Bill. It is wonderful to read this sharing of a very comprehensive thought on the current monetary policies.

From what I have learned, central bankers around the world talk to one another, and/or copy ideas from one another when they crafted their monetary policies.

The reason behind this I feel is that it will help them justify their actions. ‘Follow the norm and your back will be safe so to speak, and your jobs too’. And Who are you to comment the Central bankers’ Club policy, anyway?

So, the side effect of ‘Groupthink’ phenomenon occurred (just look at the FED, ECB, and many others whenever they gave long lectures to the public on inflation and fiscal deficit).

This mindset can be observed everywhere excepts Japan and China, where they maintain or reduced the current interest rates.

Why?

If I look at the history, Japan and China suffered quite badly from the property bubble after a long period of the credit boom (as well as the US during the Hamburger crisis).

Maybe, the FED, the ECB, and the gangs think they are ahead of the game. Hence, the seen action.

But as far as the eyes can see, there is no bubble any where except in the bathtubs.

The situation might be warranted if they might the NPLs are rising, but again property price, stock markets have not shown any signs of bubbles either, including all other asset classes even cryptos at this moment or lately.

So, I wonder if the pro rate hikes people are barking at the wrong bushes.

Time will tell whether Japan and China’s CB are right.

But based on the MMT lens, comments such as these by bills and many other MMTers, as well as, all the relevant evidences from the past and the objective analyses delivered thereafter, they and we, will be.

What is also forgotten about interest rates is that one person’s interest payment is another person’s interest income. Rising interest rates may reduce the spending power of those with outstanding loans, but they increase the spending power of people possessing interest-bearing financial assets. There are grey nomads enjoying the northern Australia warmth at present who are drinking a better class of wine for dinner in their caravans thanks to the recent interest rates hikes. Hence, on existing loans, interest rate changes only have distributional effects, not aggregate spending effects (unless the spending propensities of the two sides differ, which is probably negligible if it exists).

As for new loans, rising interest rates increase the cost of borrowing, but spending is a behavioural phenomenon. Economists conflate the behavioural and financing aspects of spending. It’s one of the reasons why economists have never come up with an adequate consumption expenditure function. There needs to be two functions – one describing the behavioural side of spending; the other describing the financing side of spending. Keynes’ consumption expenditure function is really a financing equation. A (short-run) behavioural function would be very flat for income levels below the current level and somewhat steeper for income levels above it. People attempt to maintain their current spending levels as much as possible – at least in the short-run – and adjust the way they finance their spending as interest rates rise. If they earn an income through work, they may ask for a wage rise, which can fuel inflation. They may run down past savings or they may save less from each dollar earned until interest rates fall again.

Business investment spending is very much dependent on expected sales – again. not by the cost of financing. They, too, will seek to alter the way they finance their investment spending, perhaps by running down cash reserves, adding less to their cash reserves, or retaining more of their profits. If their costs go up, they pass the cost on (given that most firms are price-setters) in the form of higher prices, as Bill says in his blog. I also believe there should be two functions describing the behavioural aspect of investment spending (accelerator theory of investment) and the financing aspect.

Overall, it usually takes very large and frequent interest rate rises before there is any meaningful impact on total spending and only after it has adversely affected many (usually vulnerable) people and helped fuel inflation, not quell it.

As for public debt, I refrain from using that term in the case of a currency-issuer. I consider any outstanding monetary payment to only be a ‘debt’ if, in order to make the payment, an individual, entity, etc. has to give up something real. Currency-issuing central governments give up virtually nothing real to make an outstanding monetary payment in their own currency – they have close to 100% seigniorage. Currency users are different. They must give up something real (sell it) to obtain the money to make an outstanding payment. Hence, the monetary payments they make constitute genuine debts.

@Phillip Lawn agree, one thing that I think is potentially making these rate rises more stimulatory than normal are the large reserve holdings at the RBA in exchange settlement accounts. At the moment we are paying ~2.4% interest on like $0.45 trillion in reserves, compared to ~$30 billion before covid, adding significant interest income that they wouldn’t be paying if they were holding gov securities instead right?

Just in my head that’s like $10bn in additional interest income, which is substantial considering we have a cth gov deficit of around $80bn at the moment

“If their costs go up, they pass the cost on (given that most firms are price-setters) in the form of higher prices”

In a price rising environment this is necessarily the case. To solve the riddle requires us to put in place an environment where firms are not price setters and are instead concerned that volume will drop more than the price rise will recover. Only in that state of fear do prices remain stable.

Arguably inflation is always, everywhere, a lack of effective competition.

What I find particularly amusing about mainstream and monetarists beliefs is that wage rises are necessarily inflationary, but interest rises are not – even though both involve taking money from one person and giving it to another.

When it boils down to it monetarists try to control the economy using the other MMT – the Monetarist Mortgage Tax. Interest rates go up, mortgage rates go up, poor people end up paying higher mortgages and rents with the interest transferred to rich depositors for safe keeping, and the poor people are unable to pass on the extra costs in their wage demands due to the systemic lack of jobs.

Bill, problematic sentence: “Bretton Woods system – because otherwise the central bank’s responsibility to manage currency liquidity to support the agreed exchange rate parities”.

I mention it because it is an important idea.

I agree with Bill Mitchell, Stephanie Kelton, Warren Mosler, Michael Hudson and all other proponents of MMT (I’m sorry if I can’t mention all, but these are the ones I ussually follow more closely), that MMT is a lens for a country’s macroeconomy, under a regime of fiat currency, issued by the country’s CB.

“Lens” means almost the same as “the algebra” behind a fiat currency.

Many others look at MMT and muddle it with “money printing”, some by ignorance, others on purpose, as to accuse someone else for the problems they create.

Ok, we all know already that “money printing” means adding zeros to a computer terminal at the CB.

Bills and coins are legacy remains of the past and CBs are doing all they can to terminate and replace them with CBDC. Hello George Orwell – Big brother is here!

But, “money printing” (let me keep mentioning it this way, for clarity purposes) can have one of two purposes: for productive ends or for non-productive ends.

If the CB “prints money” (by the trillions, as in the US) and gives it away to the elite (preaching the “trickle down” litany), who, in turn, send it away to a tax-haven, returning it to homeland (as if it was some kind of lottery prize), to buy treasury’s bonds (like a fish bitting it’s own tail), isn’t that non-productive? Isn’t that inflationary?

If productivity is going down, because nobody is building factories, nobody is building infrastructure, everybody is on a gig job, delivering pizzas, what use have we got for “extra money”?

The pizza will get more expensive, because the restaurant can’t make ends meet anymore (the gas and the electricity just got more expensive), the delivery guy has to pay extra cash for the petrol and so he demands a bigger cut of the deal, and the customer will go to his boss and demand a raise. It’s only fair to do so, but what if he’s not doing anything productive either?

MMT says: the government that issues its own fiat money can’t go broke. That’s true: but to avoid inflation, that new money has to go to productive ends, so as to make GDP grow.

GDP growth that accounts for the wealth of the society at large, and not only the elites, has is happening now.

We all know that joke that says that if I eat a chicken and my neighbor eats none, in average, we both ate half a chicken each.

Insightful comment, Phil. Thanks for that.

“Two events in the last week indicate that our policy makers have learned nothing in the 50 years since the last inflationary burst.”

What do they need to learn ?

They know fine well how it works and have done for 100’s of years.

This is exactly the reason why Central bank priorities are not the priorities of working people. The priority is of the class that set the system up to serve themselves.

The fascinating thing about the last 500 years and more is just how little economists are asked or even cited when it has come to the big economic decisions. As it has been the upper classes and the bankers working together with the establishment that have pushed through any real change. Decided between themselves what direction to take.

The big names of the economics profession have rarely ever been used and even when they are the establishment rides rough shod over the top of them eventually for political not economic purposes. Every country has a John Locke on stand by for that specific role. We have watched many John Locke’s come and go as the generations passed by.

At the end of the 17th century, and in the 18th century, the British improvised a series of changes in the way their money worked put private investors in charge of money design and that change had huge ramifications. On the one hand, it broke through old constraints on the amount of money in circulation. At the same time, it elevated the rights of creditors in new ways. And that really restructured governance and the economy. How the BOE was just a group of investors wanting to make a quick buck at the beginning.

As explained here.

https://moneyontheleft.org/2021/01/01/money-as-a-constitutional-project-with-christine-desan-2/

Of course once they had that power nothing short of a civil war will take it away from them. If you don’t believe that then just keep pretending we live in a democracy and turn up and vote every few years and see if it makes a difference. We are his majesty subjects, being human doesn’t even come into it.

Great post. What strikes me though is that none of the MS economists and media Ever drill down to the nature of national debt, such as who we owe and why debt is issued at all. Many people believe we owe China etc. they do not understand that the debt is bonds, term deposits really, easily repaid with interest at the end of the term.

Then there is the mantra of “eye watering debt” which will supposedly require spending cutbacks and/or tax increases. The average person believes this without question. It’s all too arcane so they switch off.

So called public debt is only “debt” in order to keep track of the quantum/keep score for accounting/book keeping purposes, as it is owed by and to the same entity as creditor and debtor (Treasury and Central Bank, which both exist under the same ownership on the public side of society/economy), AND the Treasury has the monopoly right to issue net currency. The Central Bank has the right to also issue currency but only with the simultaneous raising of an equal and opposite credit. How hard can it be?

Currency in the form of money is merely the activator of what is the true economy. The economy that we talk about in our capitalist world is comprised of resources that exist on the private and not the public side of society because that is where the citizens reside. That economy is the one where actors can go belly-up and bankrupt if it is not appropriately husbanded by the government as monopoly issuer of the currency. Because neoliberal neoclassical economists live in a delusional reality, where they see (or purposely spread as propaganda) the currency issuing government as operating with money in the same way as the private sector users, they spread the nonsense that public debt is functionally the same as private debt and the great unwashed have drunk that Kool-Aid. Fear and loathing in the deficit. If only it was that funny.

If the co-option of currency issuing governments and various handmaidens by a capitalised rentseeking minority to extract wealth from the majority in the operation of our capitalist world is not a crime against humanity, it should be.

The RBA Gov’s comments you cite here are a disgrace and just show how out of touch he is with what’s actually going on and what’s important to Australian society. He has so many talented economists working for him who are probably producing great analytical research, but he seems to be misinterpreting all of it. What’s more, he has no consistency! During the pandemic he constantly said he would not raise rates until wages started to rise and he wanted to get inflation back into their target band. After years of below 2% inflation figures, surely a few quarters of above average inflation are not going to be able to tell him that rates should be hiked so aggressively, even if it was the case that raising rates could reduce the inflation?! Madness.

Interesting to think about the household savings rate. I wonder how much of the decline can be attributed to increases in the Superannuation Guarantee (SG)?

I suspect a notable decline in household savings can be partially accounted for when you add back in the SG which is now 10% and going to rise further. Households have likely stopped saving for retirement as they no longer need to, but they still need to save for a housing deposit, and after taking on a mortgage are forced into ongoing saving,