I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

The last week in Britain demonstrates key MMT propositions

There was commentary earlier this week (September 26, 2022) from an investment banker entitled ‘MMT takes a pounding’. I won’t link to it because I don’t want to send traffic to their site. But it is the narrative that the financial market commentators who desire to politicise public debate and use it to attack their pet hates. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) apparently is a pet hate of this character and like many with similar biases he has been champing at the bit for some semblance of ‘evidence’ that MMT analysis is flawed. This week’s events in Britain have given them more succour. Except when you understand what has actually happened the events demonstrate key MMT propositions.

The banker I referred to in the Introduction wrote:

The global signals from the UK’s mini-budget matter. Modern monetary theory has been taken into a corner by the bond markets and beaten up. Advanced economy bond yields are not supposed to soar the way UK gilt yields rose.

So you get the drift.

MMT apparently says that fiscal positions do not matter – whereas the latest British kerfuffle indicates they do.

Well, first, MMT says that fiscal positions definitely matter and the conduct of fiscal policy is crucial to how the economy operates.

What MMT also says is that bond markets, without any offsetting government action, can run riot and create high risk private investment situations that force institutions to sell of government bonds (gilts in the British context), sometimes as ‘fire sales’, which because of the intrinsic inverse relationship between bond prices and yields, will drive the yields up quickly.

If there is deep financial instability threatened in any segment of the financial markets, which endanger solvency of some bank or pension fund, then it is clear that the panic can instigate large and rapid shifts in yields, given the way secondary bond markets work.

The fact that in history we have observed instances like this doesn’t say anything about the validity or veracity of MMT.

Second, MMT emphasises that while fiscal positions do matter, the way that the government chooses to act in relation to accompanying institutions they have created influences non-government sector outcomes.

So if a government sets in place a ‘rule’ that says it can only spend more than the taxation revenue it collects if it issues matching debt to the non-government sector and organises the debt issuing process as an auction where the investors get to determine the yields the government must pay on those issued liabilities then we can easily see yields behave like they did this week in the UK.

Conversely, if the government abandoned the debt-issuing institutions, MMT tells us that it could keep spending currency into existence and the bond markets could try ‘beating up’ whoever or whatever they chose but it would have no consequences for the spending plans.

Further, under the debt-issuance rule, a central bank (part of government) also has the capacity to ‘squeeze’ investment plans of non-government financial market players if they so choose.

This is what happened in Britain this week.

The shenanigans that we observed in now way invalidates MMT – rather it supports the key propositions regarding the capacity of the government sector vis-a-vis the non-government sector.

What actually happened?

First, we need to understand so-called Liability Driven Investments (LDI), which are financial market ‘instruments’ (products) that apply to defined pension schemes where the pension or superannuation fund has promised to pay x benefits at some point in time to the beneficiaries, and must ensure they have the appropriate asset coverage (with commensurate returns) to match the liabilities when they come due.

LDIs have grown like dramatically in recent years.

The Pension Protection Fund in the UK, which is a statutory corporation created in 2004 to protect defined benefit schemes, publishes its – PPF7800 Index – each month, which provides information of the “latest funding positions for all eligible defined benefit schemes” in the UK.

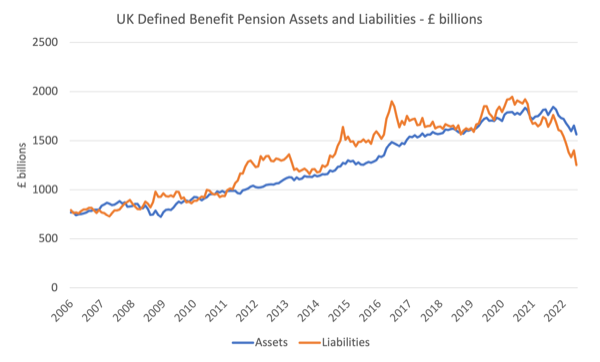

The first graph shows the aggregate assets and liabilities for UK defined benefit pension funds from March 2006 (first data collection by PPF) to August 2022 (most recent data).

The standout is the high degree of fluctuation between the two aggregates, particularly on the liability side.

The solvency of a defined-benefit pension fund (D-FPF) relies on assets growing through favourable investment returns and/or increasing its contribution base so that its ‘funding position’, its ability to meet its liabilities improves

Clearly, if the liabilities are growing then the assets have to grow and be of appropriate maturity.

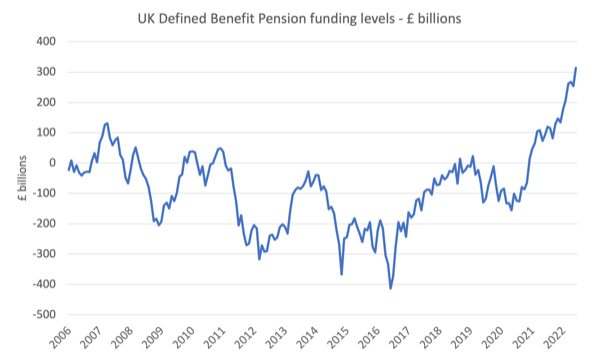

In the case of the British D-FPFs, the funding ratio (the difference between the total assets and liabilities), which is shown in the next graph, has been highly volatile and often negative.

This has mostly been driven by the volatility of the liabilities.

The purpose of a LDI instrument is to both enhace the funding ratio while reducing the risk attached to the asset base that drives this ratio.

The aim is to reduce the volatility of the liabilities by investing some of the assets in low risk financial assets, which help the pension fund minimise the liability risk, and, investing the other assets in higher risk, growth assets.

I won’t go into the detail here – it is tedious and is not needed to get the point.

But the low risk tranche of the assets are invested in such a way that they fluctuate with the fluctuating liabilities while the second tranche is designed to deliver asset growth through returns that exceed the growth of the liabilities.

In the case of the first tranche, the asset investments will be designed to rise and fall with the same key factors that cause the liabilities to rise and fall – interest rate changes, inflation, etc.

Which means if the liabilities suddenly increase, the assets will also increase in value.

If a pension fund finds itself in deficit then, then the LDI strategy will be to push assets into higher return (risk) categories to push the growth in assets ahead of the liability growth.

So what happened in the UK this week

First, the bond markets in Britain turned political, which is a story in itself – how the financial top-end-of-town now see the Tories as flagrant in fiscal policy, the beneficiaries of the recent ‘mini-budget’ being the top-end-of-town.

That is a curious development.

But bond markets regularly express political views by selling government debt off.

So what! Nothing extraordinary there.

Second, the extraordinary bit this week has been the behaviour of the pension funds.

They found their funding ratio turning ugly and had to quickly shore up their assets to ensure they could meet their on-going liabilities.

So they entered into ‘swap’ arrangements, which are regularly deployed under the LDI strategies to manage liability risks.

What? How?

A swap is just a contract where two parties agree to exchange payments into the future.

For example, an interest rate swap could involve a pension fund going to a bank and accepting a fixed rate of interest on a loan in return for an agreement to pay the bank a interest rate that is market adjusted.

Clearly, if the interest rate rises, the swap value works in the bank’s favour and vice-versa.

The important additional point to understand is that unlike using bond investments to manage liability risk under an LDI, swaps are more specific and do not require the pension fund to allocate a substantial amount of assets to buying bonds to cover the risk.

So the pension fund can get the desired liquidity now, through a swap, without tying up its assets, which can be invested to pursue returns in other investments.

There are complexities in these arrangements that I won’t go into here.

That liquidity can be used to pursue higher risk returns but the strategy can backfire if interest rates start rising and turn against the pension fund.

Most of these contracts have ‘mark to market’ conditions, which result in so-called ‘margin calls’, which are simply interim payments that the ‘losing’ party has to pay to the ‘gaining’ party.

So if the pension funds start requiring immediate cash to cover their loss positions in their swap contracts, then they have to sell any liquid assets they have on their books to get cash or go broke.

That means they are forced into a fire sale of their government bond holdings, which in the broader market increases supply and drives down the price and pushes up the yields.

The spike in yields has nothing much to do with the fiscal position of government.

Further, as the bond market investors seek to sell off bonds – the lemming rush – the pension funds face further ‘margin calls’ because their assets are losing value and the funding ratio deteriorates.

The pension funds then call their LDI managers – some of the big investment banks like Blackrock etc – to sell of assets, including government bond holdings so that they can meet their obligations under the LDI contracts.

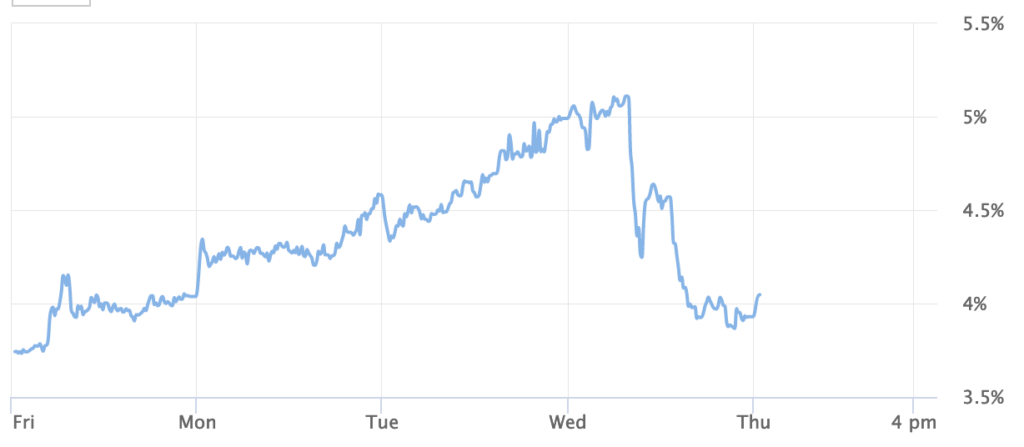

The sequence then reinforced itself – fire sale, prices fall, more margin calls, more fire sales, yields keep rising.

And so on.

One of the related problems is that pension funds are managed according to the greed principle rather than to exclusively ensure liabilities can be met.

The latter goal is relatively simple – just invest in risk-free assets that deliver a known principle at a known maturity.

So if you need $30 billion in 20 years time, the easiest way to guarantee you will have it is to buy a 20-year bond that has a face value of $30 billion.

Then whatever happens to bond prices in the secondary market is irrelevant – the pension fund just cashes in the bond in 20-years and gets the required cash.

But pension fund managers get greedy (probably because they devise salary packages that benefit from higher returns) and so they use these interest-rate swap arrangements that allow them to use the fund’ cash to pursue returns in more risky assets – like shares.

The financial market players who devise all these tricky and dangerous derivative products then prey on the greed of the pension fund managers to flog them products that seemingly will deliver massive returns.

The problem then, which was really exposed this week, is that greed leads to chaos, when the ‘models’ fail and the markets go feral.

If left to its ‘market’ resolution, some pension funds would have gone broke this week because they would not have been able to generate sufficient cash to cover their liabilities.

Enter the government

What the Bank of England did was to use its massive capacity as the currency issuer to short-circuit this bedlam.

Only the government can do that.

The Bank of England entered the long-term bond market and bought up big using its currency capacity.

The Bank issued two statements yesterday (September 28, 2022):

1. Bank of England announces gilt market operation.

2. Market Notice 28 September 2022 – Gilt Market Operations.

In its first announcement, the Bank said that:

Were dysfunction in this market to continue or worsen, there would be a material risk to UK financial stability. This would lead to an unwarranted tightening of financing conditions and a reduction of the flow of credit to the real economy.

In line with its financial stability objective, the Bank of England stands ready to restore market functioning and reduce any risks from contagion to credit conditions for UK households and businesses.

To achieve this, the Bank will carry out temporary purchases of long-dated UK government bonds from 28 September. The purpose of these purchases will be to restore orderly market conditions. The purchases will be carried out on whatever scale is necessary to effect this outcome. The operation will be fully indemnified by HM Treasury.

The second statement just outlined the operational details.

The upshot is that bond prices rose and yields fell sharply again – back to where they were last week (see the next graph which shows the UK 30-year gilt yield (TMBMKGB-30Y).

The Bank of England also wanted to moderate problems arising in the mortgage markets, where banks also fund positions using interest-rate swaps, and also faced major funding issues.

I might delve into that issue another day.

So not a case of the bond markets “beating up” MMT, but rather a case of the currency issing capacity of the government to control yields if it so chooses, a core MMT proposition.

The Bank of England’s bond purchases also caught the short selling vultures who, knowing the pension funds were in trouble and needed to liquidate quickly, were speculating that bond prices would fall even further and their short selling positions would generate profits.

Their speculative hope is that the on-going panic and liquidation of bond holdings of the pension funds to get cash drives the spot price of the bonds in the secondary market down so that they could meet their short sale contracts by buying a price below the initial price agreed in the contract.

The Bank of England squeezed those speculators and forced them to quickly cover their exposures which further drove up bond prices and drove down yields.

Conclusion

There are all sorts of characters out there who seek out the flimiest reason to denigrate MMT.

They usually posit a fictional version of MMT and compare it to the real world saying ‘see MMT is ridiculous’.

That is going on at present.

I think these characters are deeply insecure.

The last week in Britain does not invalidate MMT.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

There’s a good article in the FT that provides more detail “The reason the BoE is buying long gilts: an LDI blow-up”. I won’t link it as it is behind a paywall.

The description in the long Gilts market is correct, but what’s fascinating about the FT is that they still don’t get that driving up the short end *was the idea* of the mini-budget. They want higher interest rates. Much higher interest rates so that other MMT – the Monetarist Mortgage Tax – bears down on aggregate demand.

The ‘fiscal event’ is indeed ‘paid for’ – as far as the current government believes – by the increase in the short term rates, the withdrawal of cheap SONIA swaps, and the repricing of mortgage rates.

Those whose fixed rates are about to expire, or who are about to try and purchase a house, are the ones paying the tax.

Which will transfer the interest paid to rich people with deposits. Note the silence from Labour on that transfer to rich people in contrast to the bellicose ranting about tax cuts.

And that’s because Labour intends to pay for its largesse using precisely the same mechanism.

The British pound and economy are on the road to colapse and they need scape goats.

That’s what the right-wingers always do, whether it’s austerity that turns out to be the victims fault, or the experiments of banking into the casino business and ponzi schemes, that turns out to be MMT’s fault, even if MMT was never applied in the UK, not by the tories or by the blairites. All of them are tied up to the neoliberal guidebook, that says “print money” and give it to the elites. Elites take the money to some tax haven to laundry the stuff and then return it home, to buy treasury bonds. That’s not MMT! That’s a swindle.

What gets me is 1. the calls from some Con MPs and Labour for Chancellor Kwarteng to be sacked, but no-one suggesting that the BofE governor should resign after the BofE’s woefully slow response. Something is going on here. Seems yet more reason for the Treasury and BofE staff to be based in the same building and operating together. 2. No mention that the ECB has been keeping the EU economies going with similar intervention to provide for the secondary bond market 3. No questioning of the unfit for purpose, government subsidised private pension funds through which many are forced to be little shareholders. We need them to be guaranteeing our future financial security, as we need the water companies to be polluting our water sources and the energy companies to be ripping us off. 4. We had Chancellor Sunak trying to get us through covid by stoking house prices yet further and the current one considering offering house traders a further bung, while the BofE/govt. makes mortgagors pay more (but not the comfortably off mortgage free elderly). And no-one questions our economy’s reliance on the ludicrous housing as well as pensions market (both reliant on the govt.)

Bloomberg has let the cat out of the bag

But isn’t monetary policy supposed to magically sort out Aggregate Demand via the infinite power of expectations?

What we see here is the actual mechanism. Moving interest rates up and down is largely performance art. Government is supposed to respond to that by tightening or loosening fiscal policy. And that’s actually how the steering is connected to the wheels.

The corollary of an independent central bank is an independent Treasury, but apparently if the Treasury does their own thing that’s “fiscal dominance” and not allowed. Hence all the silly focus on fiscal rules and the like.

As I understand it from the UMKC group. The Bank of England does not BUY government Gilts. It SWAPS them back into the Reserves that bought them originally. It simply transfers the content of the Gilt from the government’s Securities Account to its Reserves Account at the Bank. The sum total of both accounts does not change. The net quantity of Treasury Sterling in the none government sector does not change. The BoE is the least capitalised Bank in the UK. To BUY the little amount of commercial Bonds it bought under QE, the Treasury had to fund the purchase.

That’s not quite how it works in the UK.

The Gilts are purchased and transferred to the securities account of Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Ltd (BEAPFF). BEAPFF then settles with the seller by drawing down on its loan from the Bank of England Banking Department.

The result on the Bank of England balance sheet is an increase in Loans Made and an increase in Commercial Bank Reserves. There is an increase in both Bank reserves *and* Bank Deposits in the non-government sector to offset the reduction in Gilts in the non-government sector. And that’s because the Gilts will be bought from the pension funds, not the banks themselves.

When commercial bonds were bought they were eventually financed in the same way – by a loan from the Bank of England. The £20bn of commercial bonds are all on the books of the BEAPFF now.

Neil Wilson

You say :

“what’s fascinating about the FT is that they still don’t get that driving up the short end *was the idea* of the mini-budget.”

What is the mechanism, from the mini buget, that drives up the “short end”?

Neil, on the basis that the BoE can’t buy much, but can loan lots to the APF, the process is just smoke and mirrors; just like the Funding-for-Lending Scheme. Otherwise QE was just a fancy Reverse Repo job.

“What is the mechanism, from the mini buget, that drives up the “short end”?”

Fiscal loosening via tax cuts will drive up inflation. The Bank of England has a 2% target and will have to respond to that loosening (under their belief system that interest rates can control aggregate demand). If the Bank doesn’t then the Chancellor will likely use his emergency powers under s19 of the Bank of England Act 1998 to enforce a change in the rates (the Bank outside its remit range for so long would definitely fall into ‘extreme economic circumstances’). Gilt market players know this and push Gilts and Bills yields in expectation of the rate rises.

Here’s what is to probably expect for at least the next 3 months regarding the Tory mini budget.

It will show the difference between MMT and the mainstream macro.

MMT:

I will use some Eric Tymoigne quotes when debating with mainstream macro regarding the mini budget.

Your proposal is to raise £45b of tax revenue: why £45b? on whom? and for what reason?

Framing it around closing the hole is not the proper way to do it. If inflation is your issue then fine but then we need to know if £45b is what is needed. May need more, may need less, who knows.

Rates will move with whatever the BoE wants to do, the fiscal side does not matter on that. We are on the course of rising rates no matter what happens on the fiscal side. Same with fx that have not much to do with fiscal balance but rather with portfolio choices.

The framing of tax policy debate should not be about how to close the fiscal hole or achieve any fiscal balance. Rather it should be about the soundness of trickledown economics and the type of income distribution (and more broadly society) we want to have.

The issue here is not the fiscal hole but rather the timing and structure of the tax policy. There is no need to cut spending or raise taxes because of the fiscal impact of the recent (insane) tax decisions, financing is going to come through.

What needs to happens is rather a discussion about the benefit of the tax policy proposed. If the goal is to impact high income and change distribution, we are going to need much higher tax rates with the aim of changing distribution rather than generating revenues.

Raising taxes by £45b to help close the hole. That’s as reckless as Tuss plan.

-we don’t know if her plan is inflationary

-don’t know size & structure of tax needed if there is an inflation issue

– £45b is stated in relation to irrelevant hole

MAINSTREAM MACRO:

Sound money – “pay for”

We need to raise taxes to fix the blackhole in the budget.

The government should keep its promise not to cut benefits for low-income families to pay for tax cuts.

We will wait for the sound money, mainstream macro GROUPTHINK report from the OBR and they will let us know how we need to fix the budget and pay for the tax cuts.

Over the next few months it is probably going to be two different approaches to the mini budget that Bill can express way better than I have done above.

It is as if the mainstream just love imposing constraints on themselves not just when they look at spending but also when they analyse any fiscal policy whatsoever. As if the UK uses the Euro and not the £ always seems to be a theme running through mainstream macro. Even if you are not constrained in the way you are when you use the Euro. The political / economic establishment in the UK certainly want you to be.

As Neil has already pointed out above even if you are sovereign. The central banks and financial markets role seems to be, to make sure to make it as difficult as possible to try and plot your own course and force elected governments to follow certain behaviours.

It’s all about power and geopolitics and doing as you are told in my view. Which leads me to one of my favourite quotes. ” Colonialism is not a historic event. It is an ongoing project. ”

I fully expect the political economists who push the ongoing project. To come out fighting over the next few months and we are going to hear a lot more about unelected, technocratic fiscal councils again. Watch this space and the usual suspects. They will see all of this as an opportunity. An opportunity to control the population the way they have always wanted to do.

Bill, this is the best summary I have read on what actually happened in the Gilt markets last week. Thank you for writing this.

It didn’t even take that much liquidity for the BoE to fix the plumbing – £5 billion a day! Instead of announcing quantities, perhaps they should just announce a cap on the gilt yield.

From a long-time reader and supporter of MMT.

Neil Wilson, your writing got me thinking – ‘Fiscal loosening via tax cuts will drive up inflation. The Bank of England has a 2% target and will have to respond to that loosening (under their belief system that interest rates can control aggregate demand)’.

My main focus is on the ‘belief system and control demand’ which makes me think of the time when I sit down and read theories, models, research papers and the vast amount of dissertations and many times, discussions thereafter, on the subjects of consumer behaviors, purchase intentions of good and services – or basically, demands, never once I see any papers mentioning about the interest rates as a significant factor in making purchase decision.

So, I ponder further again now if many people think of interest rates when they want to buy an expensive brand name smart phone (your know which one I mean) or a vehicle ones need to get to work to do your business to earn a living (or to show off your social status, or sometimes taste)?

Based on those readings and observations as far as the eyes can see – NONE!

So, now I really wonder how could the mainstream economists, or the FED, the BOE and so on have been fooling us all these times.

They are a real magician is my closet answer!

If I am right in my understanding of MMT, then according to double-entry accounting the entire financial sector adds up to zero. All that colour and movement signifies nothing. The only source of value is production, and and profits sucked into the financial system are the only source of “returns”, aside from government spending.

We are sold pension funds or superannuation on the basis that the “miracle of compound interest” will provide for our retirement, but without government spending all of these returns ultimately come from profits. So *we* are paying for the returns on our pension fund! The whole scheme is an elaborate illusion, designed to suck us all into the financial system so we all have a stake in it, thus reinforcing the dominant capitalist paradigm. That is why “the masses” so easily believe the mainstream media waffling.

Whatever you may think of our current incarnation of capitalism, you have to agree that it is a brilliant design for a self-reinforcing system. Designing a suitable replacement will not be easy.

Keating’s establishment of compulsory private pension funds was just another element of the privatisation of everything game. This has infected governments via their donor class All has been driven by an acceptance of monetarism-neoliberalism propagandised to the electors by the priesthood of neoclassical economists.

Introduction of private pension investment funds facilitated a transfer from the zero financial risk of a publicly funded pension to a privatisation of that risk. As such, it provides an overlay of yet another parasitic rent extracting (financial advisory) class, of all care (maybe) and no responsibilty, that didn’t previously exist – a group that makes money out of OPM.

Welcome to end stage (I hope) neoliberal financialised capitalism.

The core problem, in my mind, is that the government seeks to borrow the funds from the marketplace. Yet, the so called borrowing could well have come from BoE holdings of gilts – no reduction in the money supply; no increased issuance.

There is a fundamental misunderstanding of money here – gilt issuance is not a function of the government’s budget deficit, but what the BoE is trying to do with interest rates to effect economic growth. Government debt can be held ‘behind the doors’ of the BoE and have zero effect on money and interest rates.

It’s stock vs. flow. Banks aren’t intermediaries. The BOE’s response is just like the 1966 Interest Rate Adjustment Act. The Central Banks are running the economic engine in reverse.

But surely the key point is that governments should just provide decent pensions.

It the ideal is to buy long term bonds to meet long term benefits, and if currency issuing governments can always spend, then why not get rid of the pension fund middle man?

Who was it who made the absurd decision to turn pension funds over to financial speculators and what was the level of public debate?

@DFWCom indeed. How much of the FIRE sector (rent boys) could we excise? The pensions industry only functions here (UK), I’m told, because of the tax allowances. Government should provide decent, non-contributory pensions, and provide a national savings scheme which retain purchasing power. Only labour earns its return.