The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

A fiscal consolidation plan

Another day passes and lots more reading done. Some of it interesting but a significant amount of it tedious even enraging. I hum my mantras as I read to stay calm. But among the things I read there were some stand outs – not all of which I will have time to write about today. But this news report – Estonia Wants Stricter Euro Budget Rules – came in overnight, which caught my eye. Further examination, revealed how skewed policy priorities have become over the course of this economic crisis. The most costly things for an economy are ignored and aspirations that will impose future costs are promoted. Driving this policy agenda (madness) are the false messages that the IMF continually put out which spread a mélange of lies and non-sequiturs across the policy debate. I came up with a fiscal consolidation plan myself today as a result. I will disclose it later.

Estonia – update

Apparently Estonian Finance Minister Jurgen Ligi said “the euro area needs stricter fiscal controls to ensure existing members adhere to the rules”. This statement followed the EC agreeing on May 12, 2010 for Estonia to enter the EMU as its 17th member in January. Another lamb to the slaughter I thought.

Ligi, was quoted as saying:

In general we support stricter rules and control mechanisms that would prevent such financial problems in different countries … The idea of a common currency doesn’t work if fiscal policies are so different as they are at the moment.

In general, confidence is always a good asset. And Ligi is not short of that. His Ministry of Finance regularly pumps out press releases telling us how good things are. For example, in this March 4, 2010 release – Estonian General Government Budget Deficit in 2009 Clearly Below 3% of GDP – we read:

… the Estonian general government budget position in 2009 remained within the limits of the Maastricht criteria … the general government accrual budget deficit amounted to 3.7 bln EEK or 1.7% of GDP, in 2009 … Jürgen Ligi, the Minister of Finance, stated …. “… such a good result is not achieved alone by the government or one ministry, but with an effort by all of the society. In difficult times Estonia has shown remarkable strength in cooperation and budget consolidation. This stands out in the international arena …”

The achievement in 2009 was by no means a final goal in Estonian fiscal policy. “Although the deficit of 1.7% of GDP is going to be much lower than in most European countries, it is still a deficit. The expenditure still exceeds the revenues and this situation can not be sustained for a long period”, said Ligi. “Estonia has to restore the budget surplus in the coming years”.

So you get the impression that the Treasury function in Estonia is in the hands of a person with rather skewed priorities.

I have dealt with the Baltic States in the past – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism and The further down the food chain you go, the more the zealots take over. Today’s blog updates things a bit.

The 1.3 million population of Estonia is having to tolerate a government that in the midst of its worst recession as an independent nation runs a budget deficit equal to 1.7 per cent of GDP (which as I note below must be hugely contractionary) and boasts that its public debt ratio is 7.2 per cent of GDP the lowest in the EU.

Yes, and its real GDP loss and unemployment rate is around the highest in the EU. That is no coincidence. Last year the Estonian government reduced public spending by 9 per cent of GDP as it was already contracting.

Earlier, on January 29, 2010, Ligi released a press release – Euro is the result of responsible budgetary policy – in which he said:

Estonia will meet all the criteria for transferring to the euro. “We met the inflation criterion in November. We believe that Government’s decisions and efficient collection of revenues in 2009 will allow us to meet the budget criterion with a small safety margin. We will continue to improve our budgetary position in following years,” said Minister Ligi.

So you might think from reading these statement that Estonia is merging into Shangri-La. Its all about “good results” and “remarkable strength” and “efficient collection of revenues” and “improving our budgetary situation”.

Pity about the things that matter though. But then, why would we worry that real GDP is about 18 per cent lower than before the crisis began and is still falling and unemployment is now above 20 per cent and still rising and per capita incomes are still falling. Meagre detail.

The fundamental goal of the Estonian government is to get themselves into the hell-hole that is the EMU as soon as they can (next year) without regard for what else has to give to get there.

It also demonstrates how nonsensical the Maastricht criteria are that they require a nation to have 1 in 5 (at least) people unemployed for an indefinite period so that the budget numbers add up.

Estonia is also one of the IMF “deregulation darlings” and that criminal establishment has on several occasions extolled the virtues of Estonia’s currency board arrangement with the Euro and its capacity to recover quickly from the current crisis

In 2002, this IMF paper was full of self-congratulation (which seems to be an in-house style in its publications – praise ye the IMF for it is all knowing) for Estonia. It said that the currency board “made an important contribution to the early success of Estonia’s economic stabilisation and reform program”. But then the financial and economic crisis hit and the currency board system performed as its design dictates poorly and has delivered disastrous consequences for the citizens in that country.

In its December 2009 IMF Survey publication, the IMF ran a story – Baltic Tiger’ Plots Comeback – and said of Estonia:

Known as one of the three “Baltic tigers,” Estonia is now undergoing a severe recession. But unlike some other countries in emerging Europe, this small country of 1.3 million has managed to escape a full-blown crisis, thanks in large measure to prudent policies during the boom years of 2004-07 …

Estonia was hurt badly by the crisis, mainly through a decline in foreign trade. But its public finances were not as exposed as many other countries’ to the drying up of global financial markets. This was because the country had accumulated sizable fiscal reserves during the boom years and had virtually no public debt going into the crisis. That proved to be a life saver …

The government also acted forcefully to address the budget deficit when the crisis first hit … +Fiscal policy has been strong, not only during the current downturn, but more importantly, during the good years, which shows that this is a country that has an inherent, strong sense of policy discipline … [but] … Slacking off at the finish line would be an unforgivable mistake … So is there a feeling that the worst is over … the economy has most likely bottomed out, confidence is gradually returning.

So the Estonian government intent on forcing their budget parameters into the Maastricht Treaty straitjacket ran pro-cyclical fiscal policy as the economy it is meant to safeguard melted down. It is hard to describe how venal that strategy is as poverty rates rise and a generation or more of workers lose their accumulated wealth and a new generation of workers entering the labour market face disadvantage from the outset.

The other part of this which is almost unbelievable is that the existing EMU members have adopted fiscal positions that violate the Maastricht Treaty whereas hopeful new entrants like Estonia were not able to – at the threat of being denied entry. As it happens it just comes down to when you take the big hit that is built into those stupid rules. Estonia and Latvia front-loaded the misery while the worst is yet to come in Greece, Spain, Ireland etc, although Ireland and Spain are pretty well advanced down the road to impoverishment.

In terms of some background. Estonia and Latvia are not unlike Ireland is some ways but very different in other ways. The three nations were held out by the neo-liberals as the World’s so-called economic success stories in the period leading up to the crash although a significant component of the growth was tied in with real estate booms and a massive accumulation of private debt.

Now each is mired in deep recession with living standards falling rapidly and their governments are pursuing policies which will make things worse. That is the similarity.

The notable differences relates to their currency systems. Ireland is an EMU member nation and is thus straitjacketed by that insanity – Please read my blog – Exiting the Euro? – for more discussion on this point.

Both Latvia and Estonia chose, as a precursor to entering the EMU (which remains their blind aspiration), to peg their currency to the Euro and run currency boards.

Estonia pegs its currency at 15.60 krooni per Euro (after joining the European Exchange Rate (ERM) system in June 2004. Latvia pegs its currency at 0.71 lat per Euro and joined the ERM in 2005. Estonia initially pegged against the German mark when the Soviet system collapsed and they abandoned the rouble. Latvia switched their currency anchor from the IMF Special Drawing Rights bask to the Euro on January 1, 2005.

So Estonia and Latvia are both running currency systems similar to Argentina in the 1990s which ultimately collapsed and led to its default in 2001 (Argentina pegged against the US dollar). Pegging one’s currency means that the central bank has to manage interest rates to ensure the parity is maintained and fiscal policy is hamstrung by the currency requirements.

A currency board requires a nation have sufficient foreign reserves to ensure at least 100 per cent convertibility of the monetary base (reserves and cash outstanding).

The central bank stands by to guarantee this convertibility at a pegged exchange rate against the so-called anchor currency. The Government is then fiscally constrained and all spending must be backed by taxation revenue or debt-issuance.

A nation running a currency board can only issue local currency in proportion with the foreign currency it holds in store (at the fixed parity). If such a nation runs an external surplus, then reserve deposits of foreign currency rise and the central bank can then expand the monetary base. The opposite holds true for nations running external deficits.

The problem is that in those cases a crisis quickly follows because the economy has engineer a sharp domestic contraction to reduce imports but also runs out of reserves and has to default on foreign currency debt (either public or private). It is a recipe for disaster.

Anyway, all this was a precursor to some data analysis to update my understanding of what is happening in the Baltic. Today, I analysed Statistics Estonia data.

Now, in early December 2009, the IMF (as above) was claiming that the recession in Estonia was over. Now we have some more data available. Has the economy bottomed out and has confidence gradually returned.

In releasing the GDP flash estimates for the first quarter 2010, Statistics Estonia said on May 11 that:

… gross domestic product (GDP) of Estonia decreased by 2.3% in Estonia in the 1st quarter of 2010 compared to the same quarter in the previous year.

Deceleration of the economic decline continued successively already for the third quarter. In the 3rd quarter 2009, the GDP decreased by 15.6% and in the 4th quarter 9.5% compared to the same quarter of the previous year.

A deceleration in negative GDP growth is not a bottoming out. It is a further decline.

Further, “the domestic demand was small, the sales of manufacturing on the domestic market were still in downtrend. The decrease in the value added of the construction even accelerated as its output is mainly targeted on the domestic market”.

The data shows that real GDP in the first quarter 2010 was at the level it reached in five years earlier. So the Estonian economy has made no gains in real income in five years. The crisis has thus so far wiped five years of economic growth. That is a huge cost.

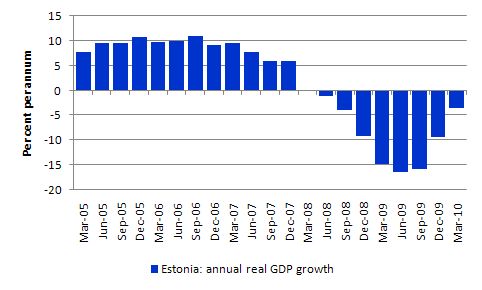

The following graph is taken from Statistics Estonia and shows the evolution of real GDP over that period.

In seasonally-adjusted terms, the nation has lost 17.7 per cent of its real income since the September quarter 2006 (when the peak GDP was reached). Per capita income is down around 15 per cent in 2009 alone.

If we translate the real GDP performance into human terms, the following report from news item is relevant – Estonia: number of jobs is the lowest in the past 25 years The statement was released on May 16, 2010, the day after Finance Minister Ligi was praising the budget figures and the progress towards entering the EMU and calling for even tighter fiscal rules.

The official labour force data release from Statistics Estonia said:

Similarly to the beginning of the previous year, the unemployment increased rapidly also in the current year. The unemployment rate rose from 15.5% in the 4th quarter of the previous year to 19.8% in the 1st quarter of the current year. In the 1st quarter of 2009 the unemployment rate was 11.4% … The unemployment was record high in the beginning of the current year … In the 1st quarter the estimated number of employed persons was 554,000, which is the smallest during the period after the restoration of independence in Estonia. Compared to the previous quarter, the number of the employed persons decreased by 4.6%, compared to the same quarter of the previous year by 9.6%.

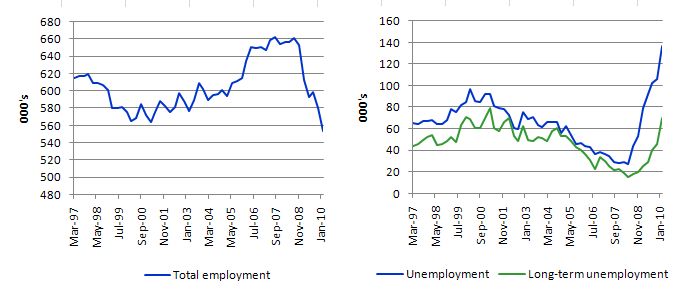

The following graphs show the sorry story. The left panel in the first graph shows Total employment in 000’s while the right-panel shows Total unemployment and Long-term unemployment (spells longer than 12 months) also in 000’s. The correspondence between employment loss and unemployment increase is nearly 100 per cent which negates any neo-liberal explanations based on supply-side withdrawal (workers becoming lazy or enjoying excessively generous welfare benefits).

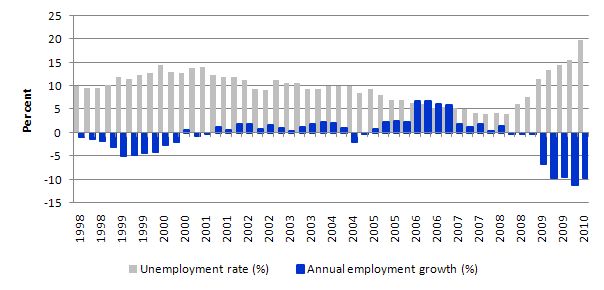

The next graph shows annual employment growth (%) in blue-bars and the unemployment rate (%) in grey bars. It is a horror story.

It is no wonder domestic demand is so low. Rising unemployment is a deflationary force and coupled with the fiscal drag there is little hope for significant improvement in domestic spending in the foreseeable future.

Note that the fact that the 2009 budget deficit of 1.7 per cent of GDP was probably highly contractionary given the extent of the meltdown in the economy. The automatic stabiliser effect on the budget balance alone would have been multiples of 1.7 per cent so you can gauge how hard they have the fiscal brakes on.

In my world of values, the discretionary fiscal position of the Estonian government represents a criminal act. By entering the EMU, Estonia will have a long period of diminished living standards and foregone income. They might have thought they were escaping the socialist yoke when the Soviet system crumbled. But it is difficult to see how things will be materially better in the space they are heading too.

Then I read the latest IMF Fiscal Monitor

I was sidetracked a little today by Estonia. The juxtaposition of the statements from the Finance Ministry and the national statistical agency in that nation was so stridently at odds that I had to make a note of it for posterity.

But my main aim was to write a little about the latest IMF Fiscal Monitor which provides a comprehensive statement of where that organisation is at in terms of its understanding and appraisal of fiscal developments over the last few years. It was not very rewarding reading I can tell you that.

The IMF boss Dominique Strauss-Kahn in his Forward to the Fiscal Monitor said this (it is a large document by the way if you intend downloading it):

The global crisis has entailed major output and employment costs, and in many economies, particularly the advanced ones, it has left behind much weaker fiscal positions.

That sets the tone for the whole document. There is only one complication with this – there is no such thing as a weak or strong fiscal position for a sovereign government. The concept of fiscal strength or fiscal weakness has no meaning for most countries.

So a rising budget deficit is not a weaker position nor is a move into surplus a stronger position. One has to judge policy positions by where the real economy is. A move into surplus with strong net exports and private domestic meeting their saving desires which results in full employment is a strong position. But a move into surplus (a la Estonia) with weak net exports and rising private domestic indebtedness and persistently high unemployment is a weak position. I could construct examples for rising deficits that would convey the same message.

Then you read this from the main text in the Fiscal Monitor:

… underlying fiscal trends have further deteriorated since the November Monitor

Except, there is no such thing as a deteriorating or improving fiscal position when we are talking about a sovereign government. The real economy can improve or deteriorate. A household’s wealth holdings can go up or down. But such descriptors are of no relevance or meaning to the budget position of a sovereign government.

Then, soon after, this:

… while a widespread loss of confidence in fiscal solvency remains for now a tail risk …

So how is the probability density function (PDF) specified that puts, for example, a sovereign debt default in Australia, the US, Japan 1.96 standard deviations or more from the mean. What is the mean? Zero?

Upon what basis is the probability distribution derived?

The point is that this is all beat-up. There is no PDF that can be reliably constructed in this context. Quite simply, the US for example has no default risk. So you would have most sovereign countries with no default risk. And a host of others with some risk. The difference between the monetary system they are working within (convertibility/non-convertibility; fixed exchange rate/floating exchange rate; monetary union/fiat currency etc).

There is thus no basis to put events that may arise in one monetary system together in probabilistic terms with events that will not happen in another monetary system.

Then, soon after, this:

… high levels of public indebtedness could weigh on economic growth for years.

How exactly? The servicing of the debt provides an income

So you get the impression that the IMF Fiscal Monitor mostly misses the point at the most elemental level.

The other problem with the Monitor, which is a recurring theme across a wide spectrum of commentary, is that they conflate fiscal outcomes in non-sovereign nations (EMU, Estonia, etc) with outcomes for sovereign countries (US, UK, Australia etc). The fact is that there is no meaningful comparison between the two groups of nations because they have different monetary systems.

You cannot understand the implications and opportunities for fiscal policy unless you also relate it to the specific operational characteristics of the monetary system in question.

So they keep quoting ratios, and averages across all the countries in their study (or subsets of them) as if they mean something. Averaging fiscal balances across the EMU and other countries is a meaningless exercise. The resulting average has no cognitive content.

But the Report provides some interesting insights into how much of the rise in public debt (and the deficits) were the result of discretionary government stimulus packages. At this point start chanting some mantra along the lines of “profligate, engorged and wasteful government spending”. Then read on.

The IMF says (Page 14):

In advanced G-20 economies, the debt surge is driven mostly by the output collapse and the related revenue loss. Of the almost 39 percentage points of GDP increase in the debt ratio, about two-thirds is explained by revenue weakness and the fall in GDP during 2008-09 (which led to an unfavorable interest rate-growth differential during that period, in spite of falling interest rates … The revenue weakness reflected the opening of the output gap, but also revenue losses from lower asset prices and financial sector profits. Fiscal stimulus – assuming it is withdrawn as expected – would account for only about one-tenth of the overall debt increase.

Did you read 1/10th?

Given the biased way the IMF decompose the actual budget outcome into cyclical and structural components the 1/10th might even be an overstatement. Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

But you can easily start to understand why the smarter deficit terrorists out there have moved onto the long-run argument and are attacking public pension and health systems. They know full well that the stimulus packages were pitifully inadequate and that is why the recession has lasted so long and has been so deep in most nations.

They know that once growth starts to emerge the automatic stabilisers will eliminate most of the increase in deficits and start eating into public debt. So to continue their attack on the public sector (to get more real GDP for themselves) they have to confuse the current situation and start introducing the ageing population agenda.

But the fact is that the fiscal stimulus packages were so politically-constrained in most countries, that governments across the world have pushed unnecessary misery onto the citizens who elected them. That is, some of the citizens – the top-end-of-town will have been less damaged if at all.

They devote a whole chapter to the “implications of fiscal developments for government debt markets” but all you get from it is:

- That governments will continue to issue debt – yes, if they don’t finally wake up to the fact that most run fiat currency systems and are not financially constrained.

- Apparently sovereign debt markets will become flooded because central banks will unwind their balance sheets – yes, but there is no reason for central banks to do so. They could just delete the accounts recording the asset purchases and no-one would be any worse off.

- That “average government debt maturities have shortened” – which means that more public debt has been issued in the maturity-ranges of the yield curve controlled by the central bank in most cases. So yields will be stable.

- That “Yields on government securities in most advanced economies remain relatively low, but spreads have risen sharply in some countries” – yes, in non-sovereign nations (they list the PIIGS). Yields in advanced sovereign nations are still low. Japan has been running yields below 1.5 per cent for years.

- That “Other indicators of the risk attached to investing in government securities in advanced economies also remain relatively muted, except in a handful of countries” – which are? EMU nations which are not sovereign.

These “insights” are followed by an array of colourful graphs that mean nothing. Not once during this Chapter does the IMF reveal an understanding of what they have concluded. That EMU nations are in trouble because of the design flaws in their monetary systems and the rest of the nations are in trouble because they have not expanded fiscal policy enough in the early months of the crisis.

On Page 28, the IMF go AWOL:

Major fiscal consolidation will be needed over the years ahead. The increase in budget deficits played a key role in staving off an economic catastrophe. As economic conditions improve, the attention of policymakers should now turn to ensuring that doubts about fiscal solvency do not become the cause of a new loss of confidence: recent developments in Europe have clearly indicated that this risk cannot be ignored.

Remember: 1/10th! Growth will wipe out the rest. What all nations still need is a significant renewed fiscal stimulus to really get the growth engines moving and to mop up the build-up of idle labour as quickly as possible. Fiscal austerity is anti-growth.

Remember: “recent developments in Europe” have no relevance for fiscal solvency anywhere else. The only relevance they have is if they provoke more private sector spending uncertainty or bank collapses which hits the start button for the global crisis again. But there won’t be a solvency issue in the US or Japan or elsewhere. They will just find they are heading back into recession.

Also on Page 28, one reads:

A distinct, but equally important risk to be averted is that the accumulated public debt, even if does not result in overt debt crises, becomes a burden that slows long-term potential growth.

This is one of the emerging strands coming out of the mainstream econometrics literature. Some studies have estimated that “a 10 percentage point increase in the debt ratio is likely to lead to an increase in long-term real interest rates of around 50 basis points over the medium run”. Further the IMF claims that new evidence “on the impact of high debt on potential growth … shows an inverse relationship between initial debt and subsequent growth, controlling for other determinants of growth”.

I have read all this literature as it has come out. It is quite technical and not suitable for summarising here. The results are highly dependent on specifications chosen and the studies typically fail to sort out what econometricians refer to as “endogeneity problems” which in laypersons language might be terms causality problems.

Countries with rising debt almost always are countries with slowing economies as a result of private demand collapses. So what is driving what? Further there is not robust relationship ever been found between budget deficits and interest rates. So the claim that most of this impact arises because interest rates are higher is unsustainable.

In general, these results that the IMF seeks to promote are not reliable and also defy a reasonable understanding of how monetary systems operate.

The IMF Monitor then spends many pages reiterating the impact of changing demographics on fiscal positions without once realising that rising dependency ratios are problematic because less people are available to produce real goods and services. They fail to understand that the real goods and services that are produced can always be purchased by a sovereign government.

So the ageing issue is not a financial problem for governments. But it will become a political problem.

Conclusion

And now … to my fiscal consolidation plan.

Governments around the world might start to reduce their fiscal positions by withdrawing all funding they provide to the IMF. This expenditure is in the category of wasteful and unproductive spending which I would always eliminate.

The IMF staff could then be retrained to address serious issues like climate change, health problems and the like. Net gain to the world.

That is enough for today!

Sounds like a good plan 😉

To further improve their fiscal position I would suggest that governments jump-start their national mints. I’ve had dinner yesterday with a friend working for the Austrian mint. They are now running 3-daily shifts because they cannot cope with demand for Philharmoniker and Gold Bullions. In the first quarter 2010 they sold 78.000 Philharmoniker. Starting with the second quarter they already sold 116.000. They sold in the second quarter 7.6 mt of Gold. In the past it was almost exclusively US and Japanese buying Austrian minted gold. Now the Germans are lining up. Sounds like good business to me.

“Meanwhile the consequences of this strong recession in Latvia – more and more Latvians are leaving in search of work elsewhere, while fewer and fewer young people feel confident enough to have children (see chart below) – will leave a long scar, which will be hard to heal, and which make the long term future and sustainability of the country even more uncertain.”

Chart

.

Demographics (1970-2010) of the neo liberal poster countries in the Baltic’s, the effect of miracle economies?:

Estonia.png

Lithuania.PNG

Population_of_Latvia.PNG

Young people don’t seems to think the miracle economies is a place for children to grow up, they are them self busy plan leaving and no one really want to move and live in the places of economic miracle

.

“Now the financial markets, the big finance houses and the mega banks batter the world to pieces with their financial sledge-hammers, and what does the politicians around the world do?

Well, when the sledge-hammers where out they supply the marauders with brand new sledge-hammers.”

Freely translated from a Swedish Blog.

It’s all very simple. The EU removes fiscal policy from the macro level, leaving only monetary policy as an option. Fiscal policy is (more or less) run by the people in a democracy. Monetary policy is run by the bankers. How convenient for the bankers to rid themselves of pesky democracy. It is just SOOOO hard to make money when you have to spread some of it aroundto the voters.

The results are clear. Estonia, with its 20% unemployment rate driving wages down, will now make a nice addition to the EU, as capitalists who aren’t talented enough to make money in any other way than to shove lower wages down the throats of their workers will now have a new home for their slave shops. Mission accomplished.

Trust me, neoliberalism is about NOTHING BUT driving down labor costs. Some of them even understand that.

If wages are driven down along with prices, then won’t this make the country more attractive in the long run? I don’t understand why printing money is required when the deflation would accomplish the same thing, and not punish savers and reward debtors like inflation does.

Recently I looked at Sweden’s official statically bureau to see the public financial standing and they had a note accompanying one of the graphs that said it “seems” like households get deteriorated financial standing when public got improved. The comment signaled that they where hapless and it was somewhat of a mystery.

The other day our Central Bank boss (former high ranking in IMF official during the Asia crisis in late 90s) gave a speech where he expressed concern about households borrowing, especially on the property market. To be honest I didn’t read the entire speech but there was nothing accompanying the concerns about household debts that mentioned the public financial position.

Interestingly I did see a graph on Naked Capitalism the other day on debt composition of Piigs, UK and Germany. Greece and Italy had among the lowest household debts. In Germany the household debt was significantly higher but company debt fairly low, so also in Sweden.

I suppose that tight fiscal policies in accompany with current account surplus In general don’t help the household sector, the external gains stay in the export industry sector.

Some numbers from Sweden:

Gross public debt % GDP

2005 _ 51,0

2006 _ 45,9

2007 _ 40,9

2008 _ 38,3

2009 _ 42,3

Projection:

2010 _ 41,3

2011 _ 39,8

2012 _ 37,8

2013 _ 34,4

2014 _ 30,3

2008 GDP got to an halt (-0,5%) and 2009 it did drop 4,9%.

Net debt % GDP, that is a surplus that make public sector one of the largest speculator on Swedish financial markets.

2005 _ -2,0

2006 _ -14,1

2007 _ -17,5

2008 _ -12,1

2009 _ -15,9

2010 _ -13,6

2011 _ -12,4

2012 _ -12,3

2013 _ -13,0

2014 _ -14,6

Interestingly gross debt as % of GDP does increase during the crisis year of 2009, there was a minor deficit of -0,8% (expected to be 2,1 this year), but the net position improves from 12,1% to 15,9%.

in Swedish crowns (billions) the same list on net position is:

2005 _ -55

2006 _ -410

2007 _ -536

2008 _ -380

2009 _ -487

2010 _ -431

2011 _ -414

2012 _ -428

2013 _ -476

2014 _ -558

(the minus sign mean that it is as surplus)

Current Account balance % of GDP

2005 _ 7,0

2006 _ 7,3

2007 _ 8,3

2008 _ 9,3

2009 _ 7,3

2010 _ 6,8

2011 _ 6,6

2012 _ 6,5

2013 _ 6,5

2014 _ 6,4

The number are from this year’s spring government bill on the budget, couldn’t find one in English.

http://www.regeringen.se/sb/d/12677/a/143864

George,

It’s not the fact that prices are falling, it’s why are they falling? I don’t understand your worry about savers, why should they be rewarded? And the government have no real choice in the matter, if they do nothing the budget will automatically go into a “bad deficit”.

Richard Koo warns: Governments That Practice Austerity Will See Their Economies Crushed, And Budget Deficits Soar

Koo is agreement with a lot of MMT positions and he is becoming quite influential. More forward motion.

“George,

It’s not the fact that prices are falling, it’s why are they falling? I don’t understand your worry about savers, why should they be rewarded? And the government have no real choice in the matter, if they do nothing the budget will automatically go into a “bad deficit”.”

Why should the savers be punished? Were the government not to steal saver’s wealth through inflation, the normal case would be that those who made bad bets get naturally punished by market forces. Nobody has to go out of their way to do this. The system would naturally clean itself out as the savers invest in a depreciated market with increased buying power. There’s no need for the govt. to do anything, unless you are proposing that people would prefer to sit on their asses when they could be doing work, and the savers can provide it by investing in factories, etc…

What you are proposing is a continuation of the mal-investment, and you reward the guys who made bad bets, and how do you do this? By spending new dollars, which reduces the value of those dollars in the hands of savers, thus stealing real wealth from them.

Dear Bill,

Another thoughtfull post. I offer some points.

1. There is no doubt that a sovereign fiat currency system faces no fiscal solvency danger. However, rates on debt traded in secondary markets , mainly long term, include an EXPECTED shortfall effect subject to a PERCEIVED probability of default, if traders follow a”rational” (really irrational!) expectations paradigm and base their opinions on mainstream theoretical models. Thus we can observe a spread over and above an inflationary expectations term. It is their impressions that count even if they are wrong! They do not learn because it a self fulfilling prophesy!

2. In models I have developed it is shown that the expected shortfall effect, if present, is worsened by the fiscal austerity measures undertaken as a response to increasing debt and this tends to raise interest rates and invert the yield curve for the expected duration of these measures. It is the austerity measures of fiscal policy that raises interest rates and spreads!

3. Sometimes, even for fiat currency sovereign debt of the longer term, there is a pure uncertainty effect as there is a rush for the refuge of the short and liquid end of the term structure or assets denominated in a reserve currency. This can be erroneously analysed as reflecting solvency danger although it is only a preference for noncommitment or hesitation to decide.

4. Finally, “animal spirits” or speculative drives (long or short) can also shift long term rates and invert the term structure as long as short term rates remain controlled by monetary policy.

George: You are assuming that every new dollar reduces the value of every existing dollar in a linear fashion. Try some thought experiments. If the government prints a trillion dollar bill and gives it to Mr Burns, who then sticks it in a display case, is that inflationary? Money needs to be spent to be able to contribute to price rises. So already things become more complicated than “amount of money = prices”.

Another one: Say an economy has 100 dollars and 100 citizens. There is a baby boom and soon there are 1000 citizens, but still 100 dollars. Will the value of a dollar decrease or increase? Seems like a constant money base would be deflationary!

So you can see that with population growth and people saving, a constant money base would actually be deflationary. In fact, it’s very clear empirically that when Australia ran surpluses for 10 years (shrinking money base) and the economy kept growing, the only way deflation was prevented was by loading up the private sector with debt.

Inflation gets even more complicated when you consider that most companies expand production before raising prices (google sticky prices). The relationship of the size of the money base with inflation is more like a flat line until full capacity (full employment) is reached, and then it’s more of a linear relationship like the one you imagine.

I never said they should be punished, but their ability to save should not be undermined either. The government has a claim on anything that is for sale in dollars, it doesn’t need to “steal” someone elses wealth through inflation.

Take for example a businessman who gets his calculations wrong and is unable to fulfill his obligations, and keeping in mind that since trade credit extends along a chain of transactions, a failure at any point in the chain can bring disaster to obligations who are upstream on the flow of credit. The suppliers who have allowed him credit may find that their resultant loss, due to no fault of their own, makes it impossible for them to pay their debts and so on up the chain. Keeping in mind that borrowings are equal to savings, hence a wealthy society, is also a highly indebted one, from your moralstic underpinnings [punished steal bad clean] you think that it is “just” for the government to stand back and let the economy collapse with all the social devastation that would cause. And all because someone can buy assets at deflated values, that were created by mal-investment.

George: “The system would naturally clean itself out as the savers invest in a depreciated market with increased buying power.”

Really? See Forecasting in Uncertain Times by Sandra Pianalto, President and CEO, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

Interesting news here on WSJ: ECB to Build New Headquarters, as Currency Stumbles It says

ECB Convergence Report talks of nine countries – Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden – bound by the Treaty to adopt the Euro and “… implies that they must strive to fulfil all the convergence criteria” according to the report. So there are other countries which are suffering too.

Good link, Tom!

Koo gets the fundamental MMT point that for MV=PY, the M is govt debt and the V is leveraging by the non-gov sector.

Raman says:

” ECB Convergence Report talks of nine countries – Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden – bound by the Treaty to adopt the Euro and “… implies that they must strive to fulfil all the convergence criteria” according to the report.”

Only two countries have an exemption and are not bound to adopt the Euro, Denmark and UK.

In Sweden the cheating and outright lies from the establishment about the Euro is immense. We did have a referendum 2003 on the Euro, the entire establishment against the people, the establishment with massive media and economic resources for propaganda to compel to vote Yes. The result was an absolutely indisputable No.

It was of course a fake referendum, the consequence if EU tighten the rules is that we had to leave EU, the Euro is mandatory. The establishment has of course no plans what so ever to leave EU, however the people vote about the Euro. And now in the middle of the crisis some parties actually think that we should have a new referendum.

Sweden have since long fulfilled the convergence criteria but use a loophole to avoid the mandatory Euro, the last step to get that darn currency is to participate in ERM for two years, by some reason the participation in ERM is voluntary. If EU takes away that loophole we have to leave EU if the voice of the people shall be respected. I doubt that the establishment respect the people that much.

“Try some thought experiments. If the government prints a trillion dollar bill and gives it to Mr Burns, who then sticks it in a display case, is that inflationary?”

I concede that it wouldn’t be, but then what would be the point of doing so? The whole point of inflationary spending is to redistribute real resources. It is no different than if men came in the night and robbed you, except it is done through stealth.

“Seems like a constant money base would be deflationary!”

And what exactly is wrong with that? The computer industry is deflationary (every year, you can get more for lower prices), has that killed them?

“Keeping in mind that borrowings are equal to savings, hence a wealthy society, is also a highly indebted one, from your moralstic underpinnings”

Only savings that are used to create a loan. If I have a real estate property generating income, what is the offsetting “borrowing” against that? If I have 100,000 in gold bullion, what is the lien against that?

“you think that it is “just” for the government to stand back and let the economy collapse with all the social devastation that would cause”

What social devastation? If people didn’t overleverage themselves, they would not run into trouble. You mean those people who were already up to their neck even at low interest rates after buying 2500 sq.ft homes? They have to foreclose? That is not social devastation, that is just a return to normalcy. They never should have bought those homes in the first place.

The one thing I’ll concede here is that if a fall is too hard and swift, then it can result in ill-advised populist programs (read: rise of hitler). However, that is no justification to bail out people who bought 2500 sq.ft homes when they never should have done so in the first place, nor is it a justification for bailout out other malinvestments.

Call a spade a spade; inflationary spending redistributes real resources by force, and it is the same as robbing someone blind. Not only are their assets worth less in real terms, but to add insult to injury, they have to pay taxes on the nominal gains!

P.S. I have a question for you guys: If the printing press is such a magical machine, and all the problems of the U.S. states (or all the problems of Greece) could be solved by given them sovereign currencies with floating exchange rates, then why stop there? Why not give each U.S. state its own currency, to keep the economy running at full capacity, but why not go even further? Why not give Los Angeles its own currency? Why don’t we give each city its own currency! Heck, with current computer technology it should be feasible! That way, each and every city is sure to be exploited to full economic potential! Say goodbye to unemployment or any other economic problems!

Can one of you explain to me why we cannot take this logic to its natural conclusion as seen above? Maybe the problem is in the whole idea of fiat currency to begin with, and not in having or not having a sovereign currency.

@George,

That does not sound like a ‘logical’ conclusion to me. You would want to extend the jurisdiction (certainly not devolve it) as far as there was a true political ‘kinsmanship’ present (see Hamilton, Alexander). There seems to be a lack of a true such ‘kinsmanship’ between a substantial portion of the population of Greece v Germany for instance, based on some of the comments Ive read in the media by lower level politicians at least.

Resp,

PS: We dont ‘print’ money. Check some of the background posts here at billyblog for desciption of current arrangements.

But then what do you do when states go bankrupt? How about cities?

It doesn’t matter if you call it printing money or something else; “changing the scoreboard” redistributes real resources and is no different than if men came in the night and physically stole that value from you. In a game, we call it cheating if you go and change the score!

What’s more, you have to pay taxes on the nominal gains, even if you lost in real terms. In addition, it is always the politically favored groups that get the new spending first. Everyone else loses as a result. Finally, no two individuals values are the same. It should therefore not be the prerogative of a central authority to push and pull on the mass of the economy as if it was a single blob.

I have read many posts on this blog. They talk about how mmt works. I don’t doubt that it works. I just think that it’s morally reprehensible, and i don’t know how or why you guys support it. Concentrating such power in the hands of a few isn’t socialism… I agree. It’s something much worse: totalitarianism.

For the record, i wouldn’t necessarily say that we should go back to a gold standard, either, as that can have its own problems and is still centralized.

However, for all the problems which mmt claims to solve, why couldn’t free banking solve them as well? No need for a govt to spend to have money and liquidity; free banking could be backet by real assets, such as land, commodities, or even energy or labour. A system where people choose the money, rather than having it rammed down their throats.

I am not against public spending, but i believe it will be much more responsible when the people are in charge of the money, rather than the elite. The political process is so corrupt… And *this* is why people are mad. They see the rot in the system and they want something better. This is something that the common man wants, and it has nthing to do with corporatism or neo liberalism. Why do you endorse giving the rotten apple so much power?

George: I can see that MMT scares you because you interpret it as greater government power, and you seem to fundamentally distrust the government, even a democratic one. My problem with that is that someone has to be in charge… if it’s not a government, it’s corporations or warlords or some other group. You seem to be grasping for some kind of system where power is completely leveled amongst everyone, and for me that is a democracy. The reason it’s corrupt I think can be traced to a lack of real, genuine education on the part of the population. The very education whose budget is repeatedly slashed by a neo liberal agenda. Under a MMT system, there would be no excuse to not have free, top quality education for everyone. To wield power the people must have knowledge! Everything else would follow from there.

“The whole point of inflationary spending is to redistribute real resources”

First of all, it’s anti-deflationary spending. Same thing, different emotional colour! I suggested that thought experiment because it’s akin to private saving. Every day people stash money away in bank reserves and leave it there, taking it out of economic circulation. This reduces aggregate demand and leads to recession spirals. New money should be created to plug that leakage so that companies don’t end up with unsold stock and start firing people. All other things held constant, if the government prints as much as is saved, demand would stay constant, everything else would stay constant, except bank reserves.

“why couldn’t free banking solve them as well”

Bill advocates that too… but that’s government banking *gasp*! It would not solve the fundamental problem of people saving instead of spending in a system that depends on people spending! Unless of course you did away with capitalism in general.

Accept that we are social creatures, and we rule the world not because of superior individual intellects but because we can work together remarkably well to do things no single person could do. There will always have to be some kind of centralization.

Wow, we got hitler, spades, confiscatory taxation, robbing of the blind, forced throat-ramming, and redistribution. Seriously, George, have you been watching Fox news or did a cat vomit on your hand as you were typing?

In a credit based monetary system, there is always inflation and deflation, as other people can bid away resources from you merely on the belief that they can earn a greater return. Even if no one saves, and even if they have no money. The belief can create money and bid goods out of your reach. And when that belief turns out to be false, all the money you thought you had in your pension account, bank deposit, and savings ends up being worth pennies on the dollar. The former is inflation and the latter is deflation. Far from “rewarding savers”, deflation and defaults shrinks the pool of financial assets that people hold. And it’s funny how everyone demands that the “speculators” take their lumps, but are completely unaware that their own retirement savings and bank savings are backed by nothing other than the promises of these “speculators” to repay.

I on the other hand, *am* aware of this, and *still* argue that aggregate financial assets should shrink — but the government should provide a safety net to let this happen in an environment that maintains aggregate demand. But you should be aware that deflation is no friend to the saver. “Free banking” is unstable, prone to financial panics and economic collapses.

“George: I can see that MMT scares you because you interpret it as greater government power, and you seem to fundamentally distrust the government, even a democratic one. My problem with that is that someone has to be in charge… if it’s not a government, it’s corporations or warlords or some other group. You seem to be grasping for some kind of system where power is completely leveled amongst everyone, and for me that is a democracy. The reason it’s corrupt I think can be traced to a lack of real, genuine education on the part of the population. The very education whose budget is repeatedly slashed by a neo liberal agenda. Under a MMT system, there would be no excuse to not have free, top quality education for everyone. To wield power the people must have knowledge! Everything else would follow from there.”

—

That’s right; when you have a group of elite that is far removed from the common man, I believe it is dangerous to give them so much power. Power can’t be distributed equally, but it can be distributed. As for MMT providing free education, that may be one of the better uses of it, but it wouldn’t really be free. There would be some redistribution needed to provide it.

“”The whole point of inflationary spending is to redistribute real resources”

First of all, it’s anti-deflationary spending. Same thing, different emotional colour! I suggested that thought experiment because it’s akin to private saving. Every day people stash money away in bank reserves and leave it there, taking it out of economic circulation. This reduces aggregate demand and leads to recession spirals. New money should be created to plug that leakage so that companies don’t end up with unsold stock and start firing people. All other things held constant, if the government prints as much as is saved, demand would stay constant, everything else would stay constant, except bank reserves.”

—

This is what I don’t understand. If money is a claim on real resources, then why is it a problem when people stash away money? Prices and interest rates would be affected by this. There’s also no such thing as spending being “only” anti-deflationary in the real world. If that was true, then money wouldn’t lose value with each and every passing year, and people wouldn’t pay taxes on nominal gains, which they do.

“”why couldn’t free banking solve them as well”

Bill advocates that too… but that’s government banking *gasp*! It would not solve the fundamental problem of people saving instead of spending in a system that depends on people spending! Unless of course you did away with capitalism in general.

Accept that we are social creatures, and we rule the world not because of superior individual intellects but because we can work together remarkably well to do things no single person could do. There will always have to be some kind of centralization.””

Of course there has to be some centralization. I said that placing such monetary power in the hands of a few is ill-advised and dangerous; I didn’t say that all centralization has to be dispensed with. Why throw out the baby with the bathwater? It doesn’t matter if it’s a government, a corporation, or a tribe; nobody should have such a disparate amount of power over others.

In my earlier comment, I omitted to mention another factor regarding the positive effect of austerity measures upon interest rates that does not work via the expected shortfall channel. This is the negative effect upon the exchange rate from the expected reduction in GDP which leads to a drop in the value of securities denominated in the currency of the economy practicing the fiscal consolidation program. The resulting rise in the rates is independent of the nature of the monetary system and whether it faces any real or imaginative possibility of state default. Notice that this interest effect will modify the usual positive devaluation channel upon the external balance.

“Wow, we got hitler, spades, confiscatory taxation, robbing of the blind, forced throat-ramming, and redistribution. Seriously, George, have you been watching Fox news or did a cat vomit on your hand as you were typing?”

—

I don’t think I mentioned hitler or confiscatory taxation (I did mention confiscatory inflation; and it is confiscatory by definition), but now that you mention it, paying taxes on nominal gains (but real losses) is kind of confiscatory, too, don’t you think? 🙂

“In a credit based monetary system, there is always inflation and deflation, as other people can bid away resources from you merely on the belief that they can earn a greater return. Even if no one saves, and even if they have no money. The belief can create money and bid goods out of your reach. And when that belief turns out to be false, all the money you thought you had in your pension account, bank deposit, and savings ends up being worth pennies on the dollar. The former is inflation and the latter is deflation.”

What you are talking about is market risk. When you invest in housing or stocks or gold or whatever, and their relative value changes because people’s valuations change, that is market risk which is voluntarily assumed and does not arise out of force or fraud, but because people’s values have changed. However, when the value is deliberately changed, as it is when the “scoreboard” is changed, then that is simply cheating. Take a game of monopoly for instance. If you play through auction, and you buy a property for a given price but then find you can’t sell it for the same price, that is because people’s valuations have changed. There was no fraud or force there, unless a bait & switch was pulled and you didn’t buy what you think you bought 🙂 If on the other hand, the value changed because someone took a few 500 bills from the bank when nobody was looking, and he can outbid everyone else, then that is simply cheating.

“I on the other hand, *am* aware of this, and *still* argue that aggregate financial assets should shrink – but the government should provide a safety net to let this happen in an environment that maintains aggregate demand. But you should be aware that deflation is no friend to the saver. “Free banking” is unstable, prone to financial panics and economic collapses.”

—

Then you need to manage the risk, instead of the current solution which is just papering over everything and pretending that risk doesn’t exist. And, what is wrong with creative destruction? People buying 4000 sq.ft homes when they couldn’t really afford it is part of the problem, and I did not agree with bailing out the bankers. The financial sector is bloated, and so were the subsidized markets, such as housing. It is the malinvestment which created many of the problems in the first place (seriously, what were people thinking?).

Do I think people should starve and die? No, I am not that cruel. However, why should they be allowed to get a free pass at everyone else’s expense? No! No matter how you spin it, for them to get a free pass means that real resources MUST be redistributed to them.

If you have a problem gambler friend, do you toss them to the street to die? No, you don’t, at least, I wouldn’t. But do you give them $1000 bills to keep playing? No, you don’t do that either! How do you expect them to learn from their experience and move on if you protect them from feeling the pain of their bad decisions?

Tom, Scott,

Thanks for following up on the links that I posted on April 25th about Richard Koo. Those who haven’t seen yet it may want to check

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=9343&cpage=1#comment-5799

his testimony to congress.

Like you, I was hoping to find support for MMT by a prominent figure, so I bought his book ( well, in fact, my first choice was Wray’s, but it was NA), and it’s a mixed picture, although in terms of actionable recommendations for gov, in the present context, he agrees with most of it. I’ll give some examples from his book, when I find the time, if it can be of interest.

“What you are talking about is market risk”

No, I am talking about something *completely* different. Allow me to illustrate with a simple fable.

Suppose that there is a peaceful Swiss village in which the economy is based on mining uranium, building bombs, and then selling them to Americans for food and drink. There is no unemployment and all output is consumed. On the one hand, people save money by investing in bonds directly, or by putting their money into a bank. On the other hand, the mining companies borrow money from the credit markets (or from the bank) and use those funds to expand operations at some constant rate, which is the rate provided to the bond holders, or split between the bankers and depositors.

Then, all of a sudden, a new man comes to town and tells them that, just over the next mountain, there is an enormous uranium deposit. One that is far deeper and easier to extract than their current deposits, and he starts up a new mining company to exploit the deposit.

He needs, say, 20% of the GDP of the village in order to start operations in one year.

Now, if this village operated according to your beliefs, then the man would not be able to start the company unless all the villagers voluntarily foregoed 20% of their consumption and saved enough in order to fund the new business. But fortunately your beliefs are all wrong. You would need to hire census runners to each household, and take surveys to determine how much consumption people were willing to give up. It would be unworkable.

But the man will be able to obtain funds without anyone saving more, and as a result, the villagers will be required to consume less, even if they did not invest in the new company. Prices will rise, and their savings will diminish in real terms, because the mining company is able to bid resources away from their existing use. Some of that will be stimulative — e.g. total output will increase somewhat — say by 10%, and say prices rise by 10% as well. Nevertheless, all the prudent savers who wanted nothing to do with the new company will still be forced to pay higher prices, and not because of government, but because some of their fellows bid up the price of the new company’s liabilities. And it does not take a lot of money to create credit. For example, by buying and selling shares of the new company, a small group of investors that maybe own 2% of the GDP of the village can cause the company to have enough purchasing power to buy 20% of the village’s output. And everyone else must put up with the rising prices.

Now when the company goes bust, then those same prudent savers that patiently put their money into the bank and did not invest in the new company will find that the bank has also gone bust, and their savings, which were diminished during the inflation, are now wiped out in the deflation. Not because of government, not because they bore risk, but because they live in a society in which investments are self-funding.

On the one hand, this means that no one needs to voluntarily forego consumption in order for a new business to start, which is good as we can dispense with the household surveys. But it is also bad because it means that the foregone consumption is achieved *involuntarily* due to rising prices. The market forces people to consume less whether they want to or not, and the heaviest burdens fall on those who save the most. And just as investments are self-funding, they are also self-defunding; when people come to realize that uranium deposit is too costly to extract, the bonds of the new firm become worthless, and this forces the leveraged banks into bankruptcy, wiping out those who did not invest in the bonds along with those who did. None of this has anything to do with government — it is the beauty of free banking. This is why anyone that ever tried free banking immediately runs to government for help. The inflations and deflations are so volatile and economically destructive that things like deposit insurance, bank regulations, lender of last resort, and all the attendant infrastructure are the inevitable end-game.

Scott Fullwiler said:

“Good link, Tom!

Koo gets the fundamental MMT point that for MV=PY, the M is govt debt and the V is leveraging by the non-gov sector.”

Not willing to concede that yet but …

In your case, why is it not M is gov’t debt plus gov’t currency?

Correct, Fed Up. I misspoke a tad. Vertical money, which is the M or net financial assets of non-govt sector, is national debt+currency+reserve balances-fed loans. If you use the measure of the national debt as Tsy’s held by private investors + Tsy’s held by Fed (which is about equal to currency, usually), then you’re about 99% there.

“But the man will be able to obtain funds without anyone saving more”

How? He can’t unless the banks expand the money supply by printing credit with no backing asset. Since you later say “Prices will rise, and their savings will diminish in real terms, because the mining company is able to bid resources away from their existing use.” is this what you are saying happened? Because this should be seen for the fraud it is and this is exactly what I am arguing against.

You are setting up a strawman and then knocking it down. The whole point is that you don’t print unbacked money which ends up devaluing everyone else’s savings in real terms; the alternative is that the guy won’t get the funds to start his mining company in the first place unless people *voluntarily* are willing to forego consumption and risk their money with him. In that case, others’ assets are not placed at risk so your scenario does not happen.

Ok, this is why you are not getting the argument. First, credit is not “printed” by banks. Second, “credit” is not “backed” by an asset. Credit is a belief in a future return of an asset, but there is always ambiguity as to what that return will be — it is not an objective decision. Even well meaning people simply don’t know ahead of time what the risk adjusted return will be. And there are feedback effects so that a random error that underprices risk causes returns to be excessively high, causing further underpricing, until the bubble pops.

Second, the credit markets can supply credit even if no banks existed. There is nothing special about banks in regards to credit creation, and the bulk of credit creation does not take the form of loans, but of equity and bond issuance. The special thing about banks is that they are able to supply credit based on an administrative decision that is protected from the credit markets as the assets are marked to model. That, and banks obtain government support.

But even without banks, the private sector is able to endogenously create (or perhaps you would say “print”) financial assets by issuing equities, bonds, and bills; the issuance of these liabilities increases the financial assets held by households, increasing their purchasing power and this can be inflationary even for those who bury their money in the ground. And when the belief in return shrinks, then households discover that they are poorer and this can be deflationary. Banks are not necessary to the inflation and deflation story, and banks can also be the victims in that the declining value of their own portfolio of bonds can cause banks to go bankrupt even if their loan book is sound. Although in practice, when there is a general credit contraction, then both will take a hit.

This is not some pathological example of corruption, but how investments are funded in an industrial economy. It is what allows us to purchase capital goods that may or may not earn a return.

Investments are self-funding out a belief that they will earn a return equal to the overall economic growth rate. If that belief is there, then they will get funded, and this means that the borrowers will bid away goods from everyone else, even those who do not lend to them.

Depending on the level of excess capacity, this will be inflationary. But that belief can and is often wrong even without introducing the element of corruption. So government or banks are not the only culprit — they *could* be the culprit — government can *also* issue liabilities, increasing the stock of the household financial assets and this could also be inflationary. Anyone who issues liabilities does this. But the credit markets can do this without any help from the government or from banks.

RSJ,

You said:

and a few more things.

That assumption is totally against the spirit of economists we interact with here. Banks have a crucial role to play in credit creation. Without banks production cannot happen. Before you point out to the role of banks in the US, and some data related to this, let me counter the argument by asking you to look at the historic roles of banks. In countries such the US, the financial markets are big and it hides the crucial nature of banks.

Some circuitists even go as far as saying that when firms issue corporate debt and equities, they are in reality reducing their debt to banks. I am totally sympathetic to the view. It is not too far fetched to say that the loanable funds market is a myth. There cannot be an economy without banks. Since banks do not need pre-existing funding, they have a special role to play. Unfortunately, they have misused this power, but thats a matter for another discussion.

Scott Fullwiler,

I noticed your interest in the QT identity turned by some such as the monetarists in a behavioral equation. If we assume the version of velocity with NFA and Py as equal to k(I+G-T) and assuming that G-T=NFA, I= Π+ΔD (profits+private debt as loans)= ΔΜ and some manipulation, one can reduce the form,

ΔΜ= (V/k + 1) (NFA), where V= NFA velocity of circulation, ΔΜ= change in the money supply, k= income multiplier.

A higher velocity parameter from risk taking preference or technological change in the financial sector and a lower income multiplier (higher MPS) requires a higher change in the money supply. There is no money multiplier here and money supply change is subject to behavioral parameters of spending and risk taking preference or technical change in financial accounts. Notice that an absolute risk taking avoidance or V=0, implies that ΔΜ= NFA.

Ramanan,

I can’t help you with that. But it seems puzzling — perhaps you should consult the handbook to verify 🙂

In terms of their ability to create credit without pre-existing funding, there is absolutely no difference between banks and the credit markets. Banks are not special in that regard. Both play the same exact role in being able to convert a belief in future returns into purchasing power to fund investment.

With the bank, you need to convince a loan officer, and with the credit markets, you need to convince others to sell some of their claims and exchange them for yours. Via this process, the total stock of credit expands in both cases, and in both cases investments are self funded and do are not priced according to loanable funds. In that sense there is nothing special about banks and banks are not needed.

This is not to say that banks do not exist and do not play an important role — of course they do. But now you are getting into finer questions of mark-to-market versus mark-to-model, and more importantly, the different types of investments that are funded. I would say that they play a complementary role, in that banks fund non-productive investments and credit markets fund capital. These are generalizations, of course, but fairly accurate ones. I think a good model should include both capital and land, and you can get a handle on things like “jobless recessions” by assuming that bank credit expansion preceededs credit-market credit expansion. I think if you incorporate both mechanisms of credit expansion, you will get farther.

You are conflating broker dealers/market makers with the lending operations of banks. Prior to Glass-Steagall, these could not be performed by the same corporate entity, but even if they are performed by the same corporate entity, the underlying funding mechanisms are different. You are correct in that prior to selling equity, there will most likely be a bank that will underwrite the sale, buying the equity first, and then selling it to investors later. I don’t think this distinction is important, and the arrangement could work in other ways as well. In any case, the bulk of credit creation does not happen via bank lending but via credit markets, and neither requires pre-funding. Therefore bank lending is not special in that regard.

And neither is subject to loanable funds arguments. You seem to believe in loanable funds for equities or bonds but not for bank loans, but I am saying that neither instrument is priced according to loanable funds mechanisms.

In terms of why the circuitists chose to put banks instead of credit markets at the center of credit creation — you would need to ask them. I think it was a general lack of understanding that credit markets create credit “out of thin air” via exactly same mechanisms as banks. But who knows?

And in terms of the historical role — I think this was always how it worked.

Credit market instruments go back to the bronze age, IIRC, these were basically standardized IOUs and promises for a share of profits (e.g. equities) that were bought and sold, and with them you could buy goods or other IOUs, therefore they took on the characteristics of money. This preceded people holding deposit accounts in a fractional reserve bank.

The modern era of finance goes back to the Mercantilist Era, and companies such as the East India Company were funded by selling bonds and equities, and these debt instruments were liquid and took on the characteristics of money — with them you could buy other bonds and equities, and so credit would expand without any prior funding. As soon as you can use your existing IOU to buy another IOU, then you have endogenous credit expansion that does not require pre-funding.

And when a nation wanted to borrow to fund a war, they did not take out a bank loan, but sold debt instruments into the market, and these debt instruments also took on the characteristics of money, etc. Generally longer term bank loans were restricted to loans secured by land, just as they are today — but of course not in every single case.

The discounting of bills is also important. Here, you have investment banks or state banks serving to make credit market instruments (bills) more liquid by agreeing to discount the bills of others while issuing their own bills and bonds. These operations are crucial to support the payment system but do not create credit. In a toy model, this is what I would have the central bank do, so I would put it at the center with credit markets creating funding for business on one side, and banks creating funding for households on the other side.

RSJ,

Not sure. Plus I have lot of “manuals”

Banks remove the supply function out of macroeconomics. Credit is always demand-determined because of the existence of banks.

It is difficult to argue what would have happened if there were no banks or less banks because that is about a debate on a universe we don’t live in. However, I am afraid, credit markets do not create credit out of thin air. There is a supply-demand mechanism without banks and credit may be restricted because of supply of credit. Thanks to banks, the supply of credit is a horizontal one, the quantity being determined by creditworthy demand.

In some countries, corporate bonds markets are small in size. Even in the US, you may quote me an FoF and tell me to compare banks balance sheets versus corporate bonds outstanding and equities’ market values. However, don’t forget, the securities created by the GSEs and the Wall Street – the asset backed securities came through bank loans.

You seem to be believing the MM theorem which effectively says “it doesn’t matter” or some such thing like that. Fortunately or unfortunately PKEists do not believe the theorem.

Yes equity markets fall in the loanable funds in my view. If they hadn’t we wouldn’t see so much fluctuations in equity prices.

Coming back to the question of creation out of thin air, credit markets do not create it out of thin air. There is a non-bank lender willing to lend and the price depends on his/her/their preferences and the quantity demanded. Banks on the other hand, set the price. The credit markets adjust to the banks’ decisions rather than the opposite. You seem to be believing in the opposite. The difference in viewpoint is big.

There are PKE models which consider the role of equities as well in good detail. There are some which include some amount of corporate paper.

The important thing I wished to point out is the fact that the role of banks is to turn an upward sloping supply curve into a horizontal one.

Well, Ramanan, I’m not sure what further progress can be made here.

You can of course look at the operational mechanisms by which credit markets create credit ex-nihilo if you are seriously interested at getting to the bottom of this.

The supply of credit is not constrained by anything other than a belief in expected return — no banks are needed. There is no supply shortage of promises, and as long as the promises are bought and sold in an orderly fashion — e.g. no payments crisis or rush to the exits — then this supply can expand endogenously without any bank involvement. I agree that such a system is fragile — no more fragile than bank lending, of course, but fragile nonetheless.

In some sense, though, I am glad, because this dispute is the heart of most of our other disputes. You (and others, I suppose) hold to a loanable funds view in the bond markets, but not in the market for bank lending. So you are a type of hybrid — half heterodox-half orthodox, depending on the instrument involved. I think pretty much all of our disagreements boil down to this one disagreement.

Now I’m interested in whether this hybrid view is shared by Bill, Scott and the other grand poobah of MMT.

In terms of quantities, the quantity of equities, bonds, and bills far surpass the quantity of bank loans in all the industrial economies, and this has always been the case.

But I agree that in many countries, the bond markets are much smaller and the bulk of the heavy lifting is done with equities, and even private equity. A lot of this depends on the institutional frameworks, whether funds are allocated by having “connections” and informal social channels are used to raise funds or whether they are allocated in competitive markets, etc.

Scott Fullwiler,

Furthermore, notice that the risk preference embedded in velocity and the savings propensity parameters can be adjusted by the short term rate controlled by the CB as V*/ (1+i) and MPS* (1+i). This can demonstrate the empirically verified negative effect of short rates upon risk taking and the positive on MPS.

ΔΜ= ( V/k (1+i)^2 +1) (NFA)

RSJ,

Yes of course, in a sense, it is at the heart of other debates. Don’t take it the wrong way but you seem to be rejecting this outright and I can just ask you to be a bit more empathetic to it.

The US central bank seems to have a lot of influence on credit markets. Other central banks have it too and I guess most central banks have it!

I have seen you writing that the Fed Funds rates have no influence whatsoever on anything. However, the non-orthodox way is very much the opposite. Of course, it doesn’t mean that entrepreneurs stop investing if the central bank rates move up – the demand depends on their animal spirits, trends in aggregate demand and indirectly the fiscal policy because it changes demand.

Some firms may try to optimize their inventories in this process. Consumers’ willingness to go into debt is also interest rate dependent. The most important thing is that the banking system has no limits whatsover on credit creation. Of course, that doesn’t mean they will lend anyone. Those things depend on the customers’ creditworthiness, banks’ own animal spirts etc.

Firms make decisions to issue equity, corporate bonds, commercial paper etc. They also decide on how much to fund internally. In fact, when I said history of the banking system, I really meant the switch from bank loans to commercial paper, because the latter was cheaper. Once the firms decide to do that – and the decision is a conscious one – and they don’t even know what the MM theorem is and wouldn’t believe it, the other sectors of the economy has to make decisions on its own and there is a supply function for bonds and equity. So there is market clearing in financial markets. On the other hand, since firms can always choose the bank borrowing route, there is enough cushion and there is no scarcity in borrowing – except maybe in times of stress.