I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The further down the food chain you go, the more the zealots take over

Today I am travelling to the Baltic States of Estonia and Latvian, both of which are mired in a very deep recession bordering on depression. What you see in these economies is a demonstration of right-wing neo-liberal ideology at its crudest … and the damage it causes … at its magnified worst. Both economies are an indictment of the economics profession and the multi-lateral agencies like the IMF and the European governments. It is hard to come to terms with national governments who could easily enjoy currency sovereignty – voluntarily choosing to do otherwise for ideological reasons and then using what policy space they have left to inflict harsh pro-cyclical cutbacks on the economies they are meant to be nurturing. It is surreal at best and sometime in the future there will be retrospective consensus that this era we are living in was dominated by cruel and tyrannical policy makers.

Title credits today come one of a very interesting series of interviews running in the New Yorker where John Cassidy is interrogating several Chicago school economists about their position on the financial crisis. In one interview Cassidy asks James Heckman whether Robert Lucas – one of the Chicago doyens should bears any responsibility. Heckman replied:

Well, Lucas is a very subtle person, and he is mainly concerned with theory. He doesn’t make a lot of empirical statements. I don’t think Bob got carried away, but some of his disciples did. It often happens. The further down the food chain you go, the more the zealots take over.

Well Lucas himself is a zealot but his type are now are running wild in the Baltic.

First some background. Estonia and Latvia are not unlike Ireland is some ways but very different in other ways. The three nations were held out by the neo-liberals as the World’s so-called economic success stories in the period leading up to the crash although a significant component of the growth was tied in with real estate booms.

Now each is mired in deep recession with living standards falling rapidly and their governments are pursuing policies which will make things worse.

That is the similarity.

The notable differences relates to their currency systems. Ireland is an EMU member nation and is thus straitjacketed by that insanity – Please read my blog – Exiting the Euro? – for more discussion on this point.

Both Latvia and Estonia chose, as a precursor to entering the EMU (which remains their blind aspiration), to peg their currency to the Euro and run currency boards.

Estonia pegs its currency at 15.60 krooni per Euro (after joining the European Exchange Rate (ERM) system in June 2004. Latvia pegs its currency at 0.71 lat per Euro and joined the ERM in 2005. Estonia initially pegged against the German mark when the Soviet system collapsed and they abandoned the rouble. Latvia switched their currency anchor from the IMF Special Drawing Rights bask to the Euro on January 1, 2005.

So Estonia and Latvia are both running currency systems similar to Argentina in the 1990s which ultimately collapsed and led to its default in 2001 (Argentina pegged against the US dollar). Pegging one’s currency means that the central bank has to manage interest rates to ensure the parity is maintained and fiscal policy is hamstrung by the currency requirements.

A currency board requires a nation have sufficient foreign reserves to ensure at least 100 per cent convertibility of the monetary base (reserves and cash outstanding). The central bank stands by to guarantee this convertibility at a pegged exchange rate against the so-called anchor currency. The Government is then fiscally constrained and all spending must be backed by taxation revenue or debt-issuance.

A nation running a currency board can only issue local currency in proportion with the foreign currency it holds in store (at the fixed parity). If such a nation runs an external surplus, then reserve deposits of foreign currency rise and the central bank can then expand the monetary base. The opposite holds true for nations running external deficits.

The problem is that in those cases a crisis quickly follows because the economy has engineer a sharp domestic contraction to reduce imports but also runs out of reserves and has to default on foreign currency debt (either public or private). It is a recipe for disaster.

This self-congratulatory IMF paper, written in 2002, concluded that the currency board “made an important contribution to the early success of Estonia’s economic stabilisation and reform program”. But the system has only just been stress-tested and is delivering disastrous consequences for the citizens in that country.

I covered the Latvian situation in some detail in an earlier blog – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism. By way of summary of that discussion the following salient points are worth repeating.

- After the Soviet system collapsed, Latvia surrendered its currency sovereignty by pegging its currency against the Euro (switching from IMF SDR parity in 2005).

- Latvia embraced all the elements of market liberalism that swamped central Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Apeing the West which was by then in full-speed neo-liberal mode they cut a swathe through government regulation and allowed the financial markets to go crazy with no oversight. International banking (particularly Swedish) gained a huge presence in Latvia and began to dominate mortgage origination.

- The government burst the massive housing bubble by contracting the economy using tax rises and public spending cutbacks. Remember its interest rates had to follow the EMU rates because of the peg. So fiscal policy had to deal with inflation rather than monetary policy which was tied up maintaining the peg.

- Further, instead of allowing the currency to make the adjustments necessary, the Latvian government is forced to pursue real depreciation (to allegedly restore competitiveness) by devastating the domestic economy. The Latvian government in response to street rioting as the economic circumstances worsened borrowed from the IMF and other European nations on the condition they implement harsh budget cuts.

- The IMF is requiring Latvia to maintain its peg and have demanded dramatic cutbacks in public spending (including health care) and higher taxes.

- The collapse in income and the rise in unemployment has pushed the current account back into surplus which takes the pressure of the exchange rate but at huge costs to its citizens.

- The currency peg is nonsensical even though devaluation would be severely disruptive given the current nominal contracts held by the Latvian private sector. Around 80 per cent of all private borrowing in Latvia is in Euro with the Swedish banks being the most exposed in Latvia. But if the Latvian government had fiscal sovereignty then it could manage this exposure better.

- Politically, a devaluation would undermine Latvia’s ambitions to join the EMU which the government claims will provide financial stability for the country.

- The government allowed the boom to go unfettered. Why did it allow around 80 per cent of mortgages to be written in foreign currency? Why did it not regulate the foreign banks that swamped the Latvian financial sector?

On December 10, 2009 the IMF Survey Magazine carried a story about Estonia – ‘Baltic Tiger’ Plots Comeback, which claimed that “(f)iscal prudence during boom years protected Estonia from worst crisis fallout” and that “this small country of 1.3 million has managed to escape a full-blown crisis”. Further, its policies are making the goal of adopting the Euro in 2011 within its reach.

When I read that at the time I couldn’t believe what I was reading given that I had been examining the data for Estonia fairly carefully at the time. I wondered what a “full-blown crisis” was if not what I was seeing in the data.

Here is a look at the latest data with comparisons with Latvia. All data is available from Statistics Estonia and Statistics Latvia.

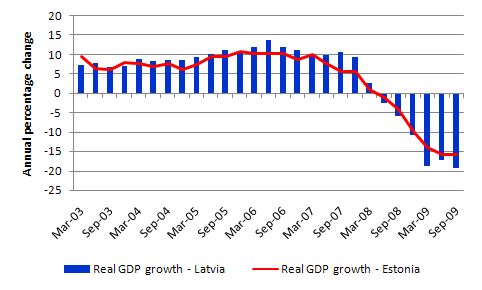

The following graph shows you how far south Estonia and Latvia have slipped in terms of annual real GDP growth.

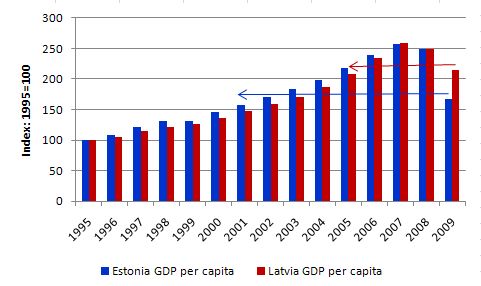

The next graph shows real GDP per capita for both countries indexed at 100. The horizontal arrows just track back to the year when per capita income was last at its 2009 value (note 2009 is December 2008 to September 2009). So Latvia is back to 2005 levels and Estonia has fallen back to its 2001 levels of real GDP per capita. However, over the same periods nominal household debt has risen dramatically (and a signficant percentage of it is denominated in foreign currencies).

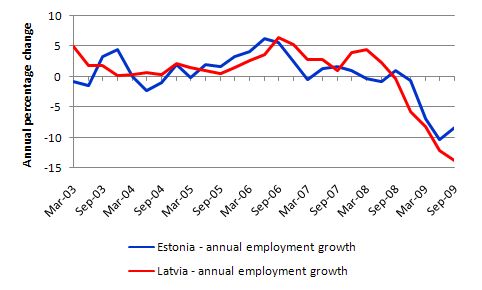

The labour market consequences have been severe. The following graph shows annual employment in each country between March 2003 and September 2009. Since its employment peak in September 2007, Estonia has lost 64 thousand jobs which is about 9.6 per cent of its total jobs stock. Latvia has fared worse. Since its employment peak in December 2007, it has lost 173.4 thousand jobs which is about 15.6 per cent of its total jobs stock. These are devastating losses and impart major deflationary forces on aggregate spending in their own right.

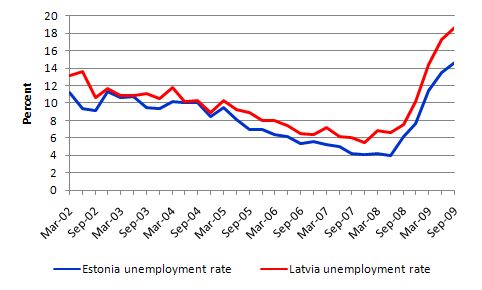

The next graph shows this labour market decline in terms of the huge rise in unemployment rates. Estonia now has 14.6 per cent unemployment while Latvia has the staggering 18.6 per cent of its labour force unemployed.

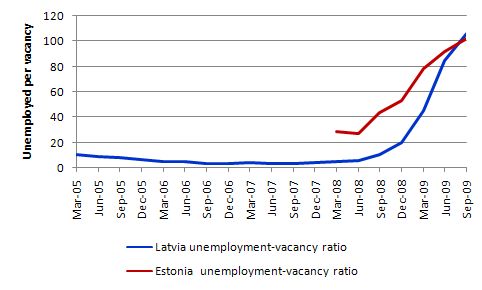

And if you want an even more scarier image of how far the policy makers have deliberately allowed their respective labour markets to slip – the following graph shows the number of unemployed per vacancy – the so-called UV ratio. For Estonia, there ratio is now at 102.3 (and likely to worsen) while for Latvia the ratio is at 105.7. The devastating effects on the morale of jobs seekers when they are up against such odds is hard to comprehend. Ratios like this are seen in poor nations not advanced technologically oriented countries.

The fact that policy makers are pursuing policies that will make this worse is unbelievable.

How long will the damage persist for? The answer is that the losses are going to be so great that the countries will never recover from these income losses, particularly as the current policies positions are making the situation worse. In other words, some age-cohorts in each country will be forever poorer as a result of the policy mismanagement.

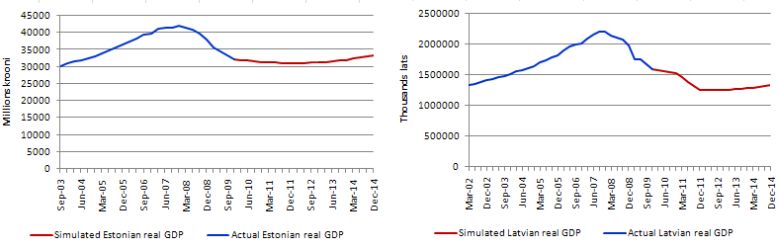

While the IMF has so far underestimated the crisis in these countries to date I took their forecasts out to 2014 from the most recent World Economic Outlook and simulated what the GDP path would be (assuming smooth quarterly transitions).

The following graphs show the adjustment for Latvia and Estonia. In Latvia’s case by 2014 they would be back at levels of real GDP that they last say in March 2002 and for Estonia levels of real GDP they last saw in June 2003. So more than a decade of lost production and income generation.

In terms of intergenerational transfers, the costs of that lost income are huge. The policy makers are making a generation of their citizens unnecessarily poorer and that they will never regain the lost income.

In last Friday’s UK Guardian (January 15, 2010), there is commentary on the Latvian economy by US economist Mark Weisbrot (Centre for Economic and Policy) entitled – Latvia’s EU handcuffs. His conclusion is most emphatic:

There really is no excuse for this to continue.

It might be cultural language nuances but the use of “really” is defensive where I come from. I would have said there is “absolutely no excuse for this to continue”.

But that aside I agree with his argument which carries the sub-heading – “Latvia shows the damage that rightwing economic policies can do – with help from the European Union and the IMF”.

Weisbrot notes that:

Latvia has set a world-historical record by losing more than 24% of its economy in just two years. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that 2010 will be another bad year, with GDP shrinking by another 4%. The Fund forecasts a fall of 30% from peak to bottom, which would surpass the US’s economic decline during the 1929-1933 downturn of the Great Depression.

However, according to a senior central bank official, the Latvian government is committed to pursuing its “pro-cyclical fiscal policy” until wages had fallen sufficiently to restore competitiveness.

Weisbrot reacts to that statement in this way:

It is difficult to imagine a government official in the US, western Europe, or indeed most countries of the world making an argument like this in public. But these are “true believers,” and they will stay the course so long as their citizens are willing to accept the punishment.

The logic of the policy is as I outlined in my earlier blog on Latvia which I summarised above – with no room to adjust the exchange rate, the only other way to make the currency lose value is to engineer a real depreciation – that is reduce labour costs and prices. The claim is that Latvia will then see a boom in net exports and recovery will commence.

Meanwhile with the majority of mortgage contracts specified in Euros (which is fixed in lats) but real estate prices plummetting – many citizens are now starting at very large net equity positions which are exacerbating the income lossed arising from unemployment.

Weisbrot says of the plan to engineer a real depreciateion:

… is theoretically possible, it is extremely difficult in practice – and even if it were to “succeed,” the disease is cured by killing the patient. Unemployment in Latvia has passed 22%, and despite its world record decline in GDP, the real exchange rate, as noted recently by the IMF, has barely moved.

The major problem now facing Latvia is that the government has voluntarily abandoned the policy tools that could make the lives of their citizens better. They have pegged their currency; they are furiously slashing their net spending (under the IMF agreement they are due to cut their net position by 6.5 per cent of GDP – a huge fiscal contraction).

The IMF are forecasting that the economy will continue to contract in 2010 as per the simulations I show above.

Monetary policy is tied by the currency board arrangement as noted above.

Weisbrot also makes the obvious point which is usually ignored by the pegging lobby:

Maintaining the fixed, overvalued exchange rate also creates enormous uncertainty that undermines investment and causes capital to leave the country. The IMF projects that an additional 1.5bn … {Euro] … will leave the country this year. Investors and depositors in this situation are worried that the currency will be devalued, no matter what the government’s stated commitment.

The government’s position is that if they devalue then not only does inflation take off but also the foreign-denominated debt explodes.

Weisbrot shows that the economy is actually in a deep deflation and the import share has collapsed – so it is unlikely devaluation will be particularly damaging from the perspective of inflation.

But he says that the “problem of loans denominated in foreign currency is a serious one, and would have to be addressed”. He suggest that this “could be done by allowing homeowners, for example, to pay back their loans in lats at the current exchange rate – with the government picking up some of the losses.”

I do not advocate the government interfering with repossession processes. A private contract is a private contract. But the government should consult with the defaulting private owner to ascertain if they want to keep their house. If so, the government should purchase the house in lats form the bank that is foreclosing at the fire-sale price.

The government should then rent the house back to the former owner for some period – say 5 years. At the end of this period the former owner would be offered first right of refusal to purchase the house at the current market price.

The government would also offer the former owner guaranteed employment in a Job Guarantee, to ensure they are able to pay the rent and reconstruct their personal finances.

This option does involve setting up an administrative process but in terms of the primary goal of a sovereign government to advance public welfare, this proposal is vastly better than the alternative – widespread defaults, fire-sales and banks pursuing homeless indebted people. There is no subsidy operating (market rentals paid, repurchase at prevailing market price); no interference into private contracts, and people stay in their homes.

In my previous blog on Latvia – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism – I covered a number of other reforms. They include:

- Like Argentina in 2001, Latvia should abandon its pegged exchange rate. While this is not seen as an option by the mainstream, in terms of modern monetary theory (MMT) – it is the only option. The painful adjustments that will follow have to be managed in other ways. It should not devalue and re-peg against the euro at a lower rate as some have suggested.

- They should definitely not join the EMU. They would continue to lose its fiscal sovereignty and become one of the peripheral EMU nations that the credit rating agencies are now preying on.

- The government should default on all foreign currency loans. The Argentinean default case study demonstrates why the foreign community is hardly in a situation to talk tough. It demonstrated, much to the chagrin of the mainstream financial bullies, that default allowed it to resume growth and advance public purpose via a domestic policy emphasis. Once a nation defaults, the problem shifts to the lender rather than the borrower.

- the Latvian government should immediately legislate wide-scale reform of its banking system. No bank should issue foreign currency loans and all assets should be kept on their balance sheets for the continuation of the loan.

- They should expand fiscal policy to underwrite domestic saving and to stimulate employment and output growth. There is an urgency to get people back into paid work and in that context the Latvian government should introduce a Job Guarantee to stop the rising unemployment and the downward spiral in aggregate demand which only worsens the credit pressures. They can buy as much labour that wants to work at a liveable minimum wage in lats. Thousands would turn up for work immediately if the scheme was introduced.

On the options, Weisbrot says that:

It makes no sense to continue to shrink the Latvian economy, with no end in sight to the recession, simply to maintain the pegged exchange rate. Argentina tried this from 1998-2001, also suffering its worst recession ever and pushing 42% of its households into poverty. After the devaluation, the economy contracted for just one more quarter and then began a remarkable recovery, growing more than 60% in the ensuing six years.

He also provides a useful insight that the IMF, which is pushing Latvia hard to scorch its economy via fiscal austerity is, however, not the principle “driving force behind these decisions – rather it is the European governments, who are putting up most of the loan money for Latvia.”

He says the IMF are coming in behind the EU governments which have, in his words, “an enormous conflict of interest” because their “banks, including those of Austria, Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France – have hundreds of billions worth of euro-denominated loans to the countries of central and eastern Europe”.

The pressure to keep the peg and make the Latvians suffer the consequences is coming from that quarter because of the likelihood if Latvia goes (devalues then defaults), the other Baltic nations (Lithuania, Estonia) and Bulgaria will probably default too.

Weisbrot concludes that:

This part of the story is familiar even to Americans who have watched as our largest financial institutions have received top priority from the government – and indeed are doing quite well right now – while millions lose their homes and their jobs. But Latvia is an extreme case, partly because the macro-economic policy is so far to the right, and exhibiting a 19th century level of brutality.

So if that is not bad enough we visit the neighbouring Estonia, one of the IMF favourites.

The IMF Survey Magazine article ‘Baltic Tiger’ Plots Comeback, which I mentioned at the outset appears to be in denial of the situation in that country.

The Survey says:

Even though Estonia is battling a 15 percent decline in output this year and a large rise in unemployment, its government is confident it can ride out the global economic crisis. So confident, in fact, that it has just announced it is close to meeting all the criteria set out in the European Union’s Maastricht Treaty for adopting the euro.

So the priority has been to meet the Maastricht criteria at the expense of the well-being of the population. This is neo-liberalism at its best – a distorted set of priorities and total abandonment of public purpose – worthy of Weisbrot’s conclusion that the government is “exhibiting a 19th century level of brutality”.

Has anyone really done the sums and added up the massive deadweight losses that are being incurred by the Estonians over a very long period and compared them to the so-called expected benefits of joining the EMU?

Have they not seen the situation in Ireland, Spain, Greece … ?

The Survey interviewed one Andres Sutt who was until recently the deputy governor of Estonia’s central bank. He was one of the co-authors on the 2002 IMF report I referred to earlier. If you trace through the creation of the central bank after the collapse of the Soviet system and the decision-making process that led to Estonia abandoning its currency sovereignty you will realise that the IMF have had their dirty hands on the country throughout the period.

Now Sutt works as a senior advisor to the IMF representing Estonia. So part of the cosy IMF club. He told the Survey authors:

… the economy was fueled by easy access to credit, channeled through foreign-owned banks, and interest rates in real terms were very low, especially for first-time homebuyers and companies. Financing constraints were essentially removed … EU and NATO membership was really a decisive moment, and gave the country a psychological boost. That explains why banks were willing to lend money to people, and people were willing to take loans, because they all felt: ‘very soon we are going to be at Finland’s income levels’

So the story is the same as in Latvia. Lax financial regulation by the authorities including the central bank where Sutt used to work. Rapacious foreign banks pushing Euro-denominated and other currencies (Norwegian krone) onto hapless consumers who only saw the bright lights and shiny new houses and could not have possibly understood the risks of borrowing in a foreign currency when your government was running a currency board.

And now the main players who caused the crisis are pressuring the Estonian government to hammer living standards to maximise what they can get out of the carnage.

The IMF claims that the Estonian government has been prudent in running surpluses during the boom period but fail to mention that in part this squeezed the private sector for liquidity and introduced greater pressures on them to borrow more to keep spending growth rolling along. They also praise the government for acting “forcefully to address the budget deficit when the crisis first hit”.

The fact that the Estonian government started to cut back its net spending very early – when most of the shift in fiscal position was being driven by the automatic stabilisers anyway was an act of vandalism.

Sutt claims that the secret for the future is to for nominal wages to fall until the real terms of trade turn back in Estonia’s favour. I imagine he has pushed into the top of the queue to take a massive pay cut!

The last word goes to one Christoph Rosenberg who is the “mission chief … responsible for coordinating the IMF’s policy advice to Estonia”. He recommends that with Estonia so “tantalizingly close” to satisfying the Maastricht criterion, that the government should add further contractionary measures to those it has already agreed should be in the 2010 budget. He said:

Slacking off at the finish line would be an unforgivable mistake.

So bash the economy to death and if it shows any signs of life … bash it harder.

There is something surreal about all of this. I am sure the Estonians and Latvian that are living through this nightmare however see the sharp edge of reality.

Conclusion

The best way for a country to work its way out of a private credit binge is to ensure people can save and that means they have to be in employment. The worse thing for both Estonia and Latvia can do is to drive unemployment up further which just continnues to undermine the capacity of workers to pay their way.

It also withdraws essential personal care services (particularly health care) at a time when the stresses would indicate more of these services are required.

The path to reform should be to float the exchange rate, as in the case of Argentina, and once that is accomplished, fiscal policy can be used to promote activity in the domestic economy and to encourage import-substitution and investment in productive activity.

MMT tells us that both the Estonian and Latvian governments can always afford to spend in their own currencies to provide employment and stimulate local industry.

Estonia, for example, has a bevy of small enterprises – high technology, light manufacturing etc. They will take years to recover if it is left to wages to adjust. And even then recovery is not certain – lower wages lead to lower productivity and it is not clear that the real terms of trade will actually turn in the favour of either country in a scale that will fill the massive spending gap left by the fiscal drag.

Both governments should understand that the slump in tax revenue does not reduce its spending capacity. As the economy recovers, the tax revenue will recover via the automatic stabilisers anyway.

Both countries are in deep recessions – bordering of depressions. Living standards have fallen dramatically. The future as poor EMU nations is equally bleak.

The MMT solution is vastly superior to the program that is currently being outlined for both nations.

Dear Bill,

Even if governments did understand MMT and the options available to them I seriously doubt they would want to bring about change.

I’m not knocking MMT or your efforts here but time and time again these bastards keep letting us all down.

Wouldn’t a smear campaign upon big business and politicians in general be more effective ?

Alan, I share your frustration. But we have to realize that capital doesn’t like fiat regimes, which give government too much control over the economy, allowing it to pursue public purpose instead of special interest agendas. Capitalists see this as a smaller share of the pie for them, even though that is not necessarily the case, since real output capacity will increase with full employment figured at ~2% instead of 5-6% by eliminating the over-sized permanent stock of unemployment that undermines the bargaining power of labor. But capital doesn’t like the prospect of higher labor cost and resists this. Moreover, capitalism tends toward consolidation, producing oligopoly and monopoly, giving rise to political oligarchy through political and intellectual capture, erecting barriers to change. Overcoming this will require a smart and coordinated strategy based on solid economic ground such as MMT provides. I believe in progress, and so I think this is in the works on many levels, as people like Noam Chomsky are pointing out.

The entire neoliberal economic system as it now exists is oriented toward capital, on the presumption that in the age of technology capital alone creates growth, which is equated with national prosperity. All the resources of capital are marshaled toward perpetuating and extending this world view. That is what globalization is all about from this perspective.

So this is a formidable opponent to take on, and it won’t be easy. However, I suppose that the American colonists have similar thoughts when they faced down the British Empire, which ruled the world at the time. As Benjamin Franklin observed, “We must hang together, gentlemen…else, we shall most assuredly hang separately.” So keep on truckin’.

Dear Tom,

good comment.

Can you give e reference to where Chomsky discusses this, please?

Cheers

Graham

Right on Tom and I can hardly wait for the imf to come to Amerika to help us with are little $ problem. Sad

@ Graham

See Chomsky’s Profit Over People: Neoliberalism & Global Order (2003), coupled with Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance (2004), The former establishes the political and economic framework, and the latter, the foreign policy and use of the military designed to create the “Pax Americana” as a new world order based on capitalistic “democracy,” de jure, but ruled de facto by the global elite in their interest. The global elite is more dynastic than many people realize. A relatively small number of families control an enormous percentage of the world’s wealth. In fairness to their point of view, a lot of these folks don’t see themselves as evil or designing, but rather benevolent and munificent, voluntarily taking on “the rich man’s burden” for the betterment of humankind.

Chomsky is hardly not alone in this critique. See for example, World Prout Assemby, inspired by Indian spiritual leader Prabhat Ranjan SarkarPrabhat Ranjan Sarkar AKA Sri Sri Anandamurti, who was imprisoned for a time by the Indian government. (This is hardball.) PROUT stands for progressive utilization theory.

Dear All,

Since this post draws an analogy with Argentina’s crisis, I’d like to ask this : although the publicly available facts and the arguments presented on this blog (in a previous post) easily convince me that

a) the IMF-friendly currency board [1991,2002) precipitated Argentina’s problems

b) Since then, defaulting and the expansionary fiscal policy has not caused havoc, contrary to predictions by mainstream economics,

a) was a response to existing problems namely hyper-inflation (1975-). It would be interesting to know, in the interest of completeness, if prior to 1991, Argentina met the 4 criteria of a “modern monetary economy”, and if so, what it is that they did wrong (such as what Bill would probably call self imposed but detrimental constraints) ?

Bill, this is a great analysis. It does seem clear that the currency pegs are unsustainable at their current levels, but I would question how feasible a free float would be (especially in Latvia given the proportion of EUR denominated private debt). Why do you not consider a managed devaluation in the order of 5-10% a possibility?

Dear Luke

Yes, the big issue is the foreign denominated debt held by households in their housing. That is like an iron ball around their ankles now and that is why I would probably think a managed default with is best.

But a managed devaluation (of the order you mention) has certainly been discussed even at the IMF level. And to some extent it would be a short-term improvement. But it still locks them into an unsustainable peg, limits monetary policy and keeps fiscal policy from improving domestic demand. It is also not clear what a free float would deliver in parities anyway. While many will say it will plunge badly the actual depreciation is unknown.

Given there has been a significant drop in its import share (of total spending) and deflation is now the problem – how much damage (other than the Euro debt revaluations) would arise from a significant depreciation. But yes – I agree, they had to make some decisions about the debt.

best wishes

bill