The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Life in Europe – another day, another (futile) bailout

Last Wednesday (May 5, 2010) I wrote that Bailouts will not save the Eurozone in response to the miserable plan put forward to take the Greek government out of the bond markets for a period. Yesterday they announced a major ramping up of the credit line they are offering which is more characteristic of a fiscal rescue than anything else. However, it amounts to the blind leading the blind. The euro funds to finance the credit line are coming from the same countries that are in trouble. There are no new net financial euro assets entering the system as a consequence of this €750bn bailout plan and, ultimately, that is what is required to ease the recession and restore growth. The restoration of growth will also ease their budget issues. But this is Europe we are talking about. Despite the nice cars and bicycles they make, they are not a very decisive lot and their institutional structures are hamstrung by an arrogant sclerosis that pervades their polity and corporate world.

Apart from the obvious consistency issues that these “bailouts” pose for the design and rules of the EMU, the fact is they are missing the point. The problem lies in the flawed design of their system.

I particularly liked this opening gambit by UK Guardian commentator Larry Elliot in his May 19, 2010 article – IMF has one cure for debt crises – public spending cuts with tax rises:

Deadly riots. Public sector unions taking to the streets. An austerity package of mouthwatering severity. The news from Athens last week could mean only one thing: the International Monetary Fund had been in town.

That about says it all. Elliot puts the only question that needs to be answered “Why is it that the IMF’s medicine for Greece is exactly the opposite of what every other country did to stave off recession?”

What does the IMF and the EMU bosses think will happen in the countries they are imposing these austerity plans on?

First, the IMF knows that the “immediate prospects for the Greek economy … (are) … bleak” (quote from IMF boss Dominique Strauss-Kahn). They know full well that trying to cut a budget deficit when an economy is in a deep recession devastates local demand and economic growth.

Second, these austerity programs used to be called SAPs (Structural Adjustment Programs). They are deliberately designed to ensure that the public-private balance in an economy is irrevocably altered towards free markets and private production at race-to-the-bottom wages and conditions.

They promote environmental degradation as export markets are sought and local resources exploited with abandon. They promote significant increases in economic inequality as the wage share is cut in the hope that private investment will be stimulated.

They promote rising foreign-currency indebtedness as the “investors” move into pick the carcass made available at rock-bottom prices by privatisation. They promote foreign entry into service provision as the public service is hollowed out via outsourcing, contracting out or straight-forward privatisation.

That is the nature of the structural adjustment that the socialist Greek government is signing up for just to remain in the Eurozone. It is a price that is not worth paying given the experience of other nations that went through the same process during the 1980s after the Latin American debt crisis.

And the point is that it is totally unnecessary. The debt crisis is a mindless ideological construction. I am not saying the debts are not real and the Greek government is not liable. Obviously it is. But the choice to get itself in this position is totally voluntary.

It was obvious from the start of the EMU that it would be shown to be vulnerable to exactly these problems the first time it faced the stress test of a serious economic downturn. That downturn arrived – more serious than most – and the fatal design flaws in the EMU arrangements were there for all to see.

By surrendering their life jackets, it was obvious they would drown when the first big wave came – the weaker swimmers first and the stronger ones will follow later.

This ideological slant of these austerity programs is not headline news. It is all about fiscal responsibility and living within your means. But imagine if the taxe rises were aimed at the corporate sector or the high income earners and the spending cuts on corporate welfare and military expenditure. Imagine if luxury cars and clothing and wines were banned to “improve the current account”. Then the ideological nature of these impositions would become transparent. There would be such an outcry the world over.

The other point to note that the IMF intervention often masks a failed polity. Larry Elliot says:

History suggests that there are occasions when the fund’s intervention can help to restore confidence, often by simply providing cover for governments facing strong domestic opposition to unpalatable policies. In 1976, Callaghan and his chancellor, Denis Healey, agreed with the fund that cuts in public spending were needed, but knew it would be hard to get them past the trade unions and the left wing of the Labour party. Protracted, often bitter, discussions, both between the British government and the fund and rival factions in the cabinet, ended with deep cuts in spending in return for financial support for the pound.

So an unelected and unaccountable body is used as the Trojan Horse to undermine democracy. The point about democracy in my view is that it can lead to failed outcomes which generate costs that have to be borne by those who vote for the governments. I know the distribution of the costs of these failures are never proportionate.

But, in general, it is better for people to decide on public spending cuts rather than having them imposed. However, before deciding on spending cuts, the political debate has to determine what is the acceptable balance between public and private – or social and private and what level of benefits the country will support.

These choices are not of a financial nature. They relate to how the real pie is to be constructed and shared and how to use real resources in the future. If sacrifices and compromises have to be made to ensure that all competing demands on the available real resources are rendered compatible then these resolutions have to be reached politically.

By dressing the trade-offs as financial imperatives and then forcing one particular solution on the people, which reflects the mindless and failed IMF ideology is the anathema of democracy.

Most importantly, I would also note that in the British case in 1976 and the Greek case in 2010 – the lack of currency sovereignty was the cause. Britain was trying to hang on to some sort of corrupted peg even though the Bretton Woods system had completely collapsed in 1971. Greece gave up all sovereignty by joining the Eurozone.

Elliot also quotes Joseph Stiglitz who criticised the way the IMF dealt with the nations following the break-up of the Soviet Union:

The IMF kept promising that recovery was around the corner. By 1997, it had reason for this optimism. With output already fallen 41% since 1990, how much further was there to go?

You can still see the legacy of the IMF programs in these nations. I have been doing work over the last year in the old Soviet STANS (in Central Asia). There isn’t a lot to show for the 20 years of market liberalisation and privatisation that the Washington terrorists imposed on these nations. There are a few oligarchs who snaffled the privatised wealth. But there are thousands more who lost guaranteed superannuation that they had worked for their whole lives, and thousands who now have sub-standard housing and pay “market rents”.

Given the real resource wealth of these nations (barring some) the process of dismemberment could have been handled much better. A wider sharing of prosperity would almost certainly have resulted from a domestic-oriented full employment policy with a focus on first-class education, health and aged-care.

Elliot then quotes a former OECD economist who drew a parallel between the current crisis and the Asian crisis in 1997-98. Both were caused by failures in the private sector rather than the public sector and originated from “(m)alfunctioning banking systems”. The IMF – the one-trick pony – claimed the problems were caused by excessive government and not enough deregulation and demanded “cuts in public spending, higher taxes and lower government subsidies” in return for loans to restore foreign reserves.

The former OECD economist said of this:

The fund came in and prescribed fundamentally the wrong medicine. If the problem is a lack of private demand, the right approach is for governments to spend and to prevent the banking system from collapsing. The IMF told them to do the opposite. Politically speaking, it was a disaster in Asia. It was a searing experience for them and made Asian countries very sceptical about anything the west said. The west compounded that by doing exactly the opposite when it was our turn to face problems. Having gone through that experience they vowed individually and collectively ‘Never again’ and set about systematically building up their reserves.”

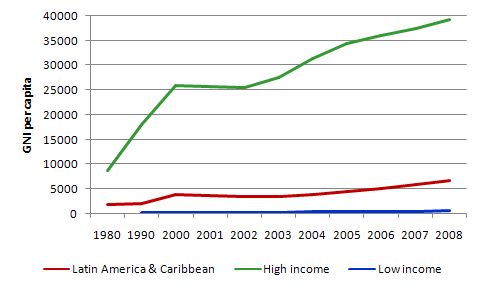

The failures go back in history though. Remember this graph which I posted last year and declared my chart of the year in my annual awards. The narrative for the chart was also presented in more detail in this blog – IMF agreements pro-cyclical in low income countries.

The graph uses World Development Indicators data, provided by the World Bank and shows Gross National Income per capita, which, in material terms is an indicator of increasing welfare.

The overwhelming evidence is that these programs increase poverty and hardship rather than the other way around. Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa (which dominates the low income countries) were the regions that bore the brunt of the IMF structural adjustment programs (SAPs) since the 1980s.

While the high income countries enjoyed strong per capita income growth over the period shown (since 1980), Latin America (and the Caribbean) has experienced modest growth and the low income countries actually became poorer between 1980 and 2006.

The two trends are not unrelated. The SAPs are responsible for transferring income from resource wealth from low income to high income countries.

So Greek is signing up to this sort of destruction and life will not be the same after the IMF is through with them.

Greece will grow again in the future and the IMF will claim another success. It did the same with the South East Asian economies that it decimated in the late 1990s. They eventually grew but their recovery was unrelated to the IMF input.

Elliot uses one of my favourite anti-IMF examples to some effect. He says:

In the aftermath of the Asian crisis, the bigger emerging economies became warier of the fund. Russia defaulted on its debts in 1998, while Argentina, which had been the IMF’s poster child during a decade of austerity after 1990, abandoned its programme entirely in 2001 – deciding that default and devaluation was preferable to indefinite economic agony. The fund warned that the result would be pariah status, deep recession and hyper-inflation; Argentina actually grew by more than 60% over the subsequent six years.

And they successfully defaulted on their foreign-currency debt exposure although there is now signs of conservative forces emerging in that nation again which will begin the process of bond-market dependency all over again.

The fact is that Russia and Argentina and Greece all surrendered their currency sovereignty and, in doing so, created unsustainable positions for themselves. The IMF solution is to stop them regaining their currency sovereignty because they would be virtually out of a job if nations took control of their own affairs. Clearly in taking control default on the past “tainted” obligations is the best option.

This is anathema to the IMF and its private banking cronies because then there pillage of the nation’s resources is brought to a stop. As a note, I used the word tainted to describe obligations built up when a nation is not sovereign but is rather operating under the constraints imposed by a foreign currency.

Anyway, last week is was a €110bn bailout plan for Greece, this week it is a €750bn bailout plan for the entire currency union. Next week, ?.

Despite all the posturing and failure to acknowledge the real problems inherent in their monetary system, the pompous EMU bosses are inching closer to admitting – by their actions – the obvious. The Eurozone is built on flawed foundations and cannot work when there are serious demand crises.

Even in a general growth environment, the system cannot deliver reasonable living standards across the entire bloc.

So the €750bn package is recognition – finally – that their system is in a state of collapse. As the UK Guardian says (Source):

… this time the kitchen sink has been thrown at the problem.

An optimistic interpretation of the latest package is that it is signalling a need for a EMU-wide fiscal capacity, one that was denied in a bloody minded exercise of neo-liberal ideology with overtones of racism at the outset of the union. Clearly, Germany is still dominating the debate and they are dead against bailouts particularly when aimed at helping the indolent and haphazard southern Latinos they sell all their crap military equipment to (the racist overtones).

So I don’t expect progress on that front.

As I have noted previously, the sovereign debt issue is one thing, but the crisis is spreading to the banking system. A run on the banks in Europe will end their monetary system and force the ECBs hand. So things will get worse unless something major happens there.

The make-up of the credit line (between EU/EMU/IMF) is largely irrelevant from a monetary perspective. When you distil the hype you come to the conclusion that the troubled nations are just lending to themselves – as they have to because the bailout is in Euros. But this cannot provide a sustainable solution.

Budget deficits are flows – daily flows which under their monetary system require continual funding from external markets. If those markets refuse to fund any particular national government in the Eurozone then the EU has to step in. That is the basis of the lifeline announced yesterday.

You cannot eliminate these deficits in any short-time span. As the national governments roll over debt to raise funds for their net spending obligations the fund will prove to be inadequate.

Given the austerity packages that will accompany the bailouts, I expect the budget deficits to worsen as the austerity packages are implemented in Greece. So the austerity packages are going to increase not decrease these funding requirements.

So only will these austerity measures worsen and prolong the recession but the funding needs will expand. Given the way the EMU monetary system is structured, the Greek government will have to keep placing debt in the private bond markets or drawing on the EU bailout credit line. This need is what has brought the Eurozone to this point. It is going to get worse.

The Greek government cannot possibly satisfy the demands that are being placed on it, given it is hamstrung by the internally inconsistent EMU Treaty rules?

The problem is the lack of capacity of these national governments to issue their own currency. Under current institutional arrangements I cannot see the bailouts working. They will have a short-term palliative impact only on the bond markets but cannot overcome the intrinsic dysfunction in the Eurozone structure which has led to this crisis.

Within the logic of the EMU, there are only two outcomes: (a) The EU governments keep tipping bailout funds into Greece and then Spain and onto Portugal – without resolving the basic dysfunction in their monetary system; or (b) Greece will have to default and preferably leave the EMU.

In the context of the first outcome, the point this week (May 10, 2010) by the President of the European Commission in Brussels is of relevance:

The important point common to all these agreed elements today is that we will defend the euro whatever it takes. We have several instruments at our disposal and we will use them. The European Institutions – Council, Commission, European Central Bank and of course the Euro area Member States. This was the clear decision unanimously taken today.

Which brings us to the more obvious short-term solution – which staring them in their arrogant faces – the ECB is more than capable of injecting net financial assets denominated in Euros into the EMU system. It is the only entity that can make truly vertical transactions in euro.

So at present what is it doing? Managing liquidity to ensure the interest rate stays where it wants it.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the ECB is the only entity that inject the required net financial assets into the system. I doubt it will do this. I suspect they are hoping that the declining Euro will stimulate net exports sufficiently to inject growth into the region.

However if you think about that – the benefits of the declining euro will almost assuredly be appropriated by Germany and France and Benelux nations while the troubled southern European countries will enjoy very little gain. They would benefit if they could depreciate their own currency but given the disparate relative competitiveness within the EMU, the euro decline is unlikely to help them.

With Germany steadfastly refusing to expand domestic demand the net export bonanza will allow them to reduce their budget deficit without as harsh a domestic contraction that it is forcing – through the EU – onto Greece and soon Spain and then Portugal and Italy not to mention the hapless Irish.

No time to be a pensioner in Europe I would think.

Anyway, I have to write a piece for the press on the Federal Budget over here now.

So that is enough for today!

“the ECB is more than capable of injecting net financial assets denominated in Euros into the EMU system. It is the only entity that can make truly vertical transactions in euro.”

how so?

The EZ national governments make vertical transactions through their budget deficits. It’s no different operationally than the case for a currency with a single national issuer.

how does the ECB inject net financial assets in Euros? What does it buy to achieve the net?

if ECB buys secondary market debt (i.e the plan), that doesn’t change the net vertical configuration in total

do you mean the ECB buys new issue national debt? is that what you mean by “truly vertical”?

I empathize with Anon.

Not sure why the ECB has to increase its balance sheet for the Euro Zone to grow. In a simplest mental model, the ECB may have a balance sheet just enough to provide banks with the cash they need for their customers and provide advances to banks to help them satisfy their reserve requirements.

Of course that is gross simplification I understand but if various sectors in the Euro Zone purchase government debt, the sectoral balances still applies It may affect some countries, no doubt but if there is some assurance of protecting the governments, I do not see why the ECB purchase is needed. In fact, as Greenspan mentioned, if you have a bazooka in your pocket and others know it, you don’t have to use it. The government debt increases in nominal value and the private sector net worth increases as a consequence. No need for the ECB to actually “inject” anything.

At any rate, according to the Bank of Finland, all NCBs have started purchasing government debt.

Dear Anon and Ramanan

My point was that the ECB has to become like a fiscal authority. For example, a per capita transfer to all member state treasuries from the ECB would be sensible right now. It is not within the rules but nor are the bailouts.

The point was to expose the lack of fiscal flexibility to deal with the crisis.

best wishes

bill

“My point was that the ECB has to become like a fiscal authority. For example, a per capita transfer to all member state treasuries from the ECB would be sensible right now.”

You and Warren Mosler seem to share the same idea.

What you’re suggesting on the one hand is that the ECB be extended to a supranational treasury function.

The two together would constitute the type of integrated G/CB entity at the supranational level proposed by MMT more generally at the national level.

That allows direct deficit spending by the supranational government entity (as per your transfer), creating net vertical financial assets equal to supranational Euro liabilities.

But it’s a fine line between primary “financing” (supra fiscal as per above, without purchase of national debt) and secondary market “financing” (supra CB monetary, with purchase of national debt).

The end result is effectively the same in terms of net financial assets – currency, reserves, national government liabilities PLUS (supranational liabilities issued MINUS any national liabilities purchased by the supra CB).

Bill, hello from Norway and long time no see. I agree with all you say here. But there is a crucial difference between the UK and the Euro countries that at least here in Norway is severely undercommunicated and not understood by pundits and the media: The UK still has its own currency and may create more pounds via its CB to pay all pound-denominated debt. And I believe that most of it (“gilts”) is in pounds. (Do you know how much if any of UK gvt. debt that is denominated in other currencies?) This constitutes an enormous advantage for the UK in contrast to the Eurozone countries. Similar for EU-members Sweden and Denmark.

Dear Trond

Welcome to my blog (and soon to visit Newcastle).

I make this point relentlessly. I say it so often that I see it in my dreams.

Currency sovereignty is not a cure to economic problems but it sure beats not having it.

best wishes

bill

Troind Andresen asks “Do you know how much if any of UK gvt. debt that is denominated in other currencies?

I have never heard the slightest whisper about any significant proportion of the UK’s national debt being denominated in a currency other than sterling. This article seems to confirm the point: http://www.efinancialnews.com/story/2009-07-06/banks-press-uk-to-issue-foreign-currency-debt

As to the proportion of UK national debt held by non-UK entities the following sources give a figure of about a third.

http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/economics/uk-debt-held-by-oversees-investors/

http://www.debtbombshell.com/bond-market.htm

Food for thought.

The share of public debt owned by the foreign sector induces an income drain and reduces domestic tax revenue worsening the public deficit, especially for a regime of revenue constraint and debt finance of the budget balance.

Using national income accounting the share of the domestic debt finance issue is equal to the primary budget deficit as a share of GDP which means that the gap between the real interest and the real domestic growth share of the budget is equal to the share of foreign debt ratio. Notice that the real yield for the term structure is affected by the probability of default and the expected shortfall which is moderated by the solvency ratio (which includes real estate, productive capacity and private domestic net savings). This gap can decline only if the real GDP growth of the private sector is accelerating, they mantain a net export surplus and the solvency ratio is increasing. In EU economies this can be a serious problem, especially if they have a high share of foreign owned debt.

Michael Hudson’s take: Euro-Bankers to Greece: The Wealthy Won’t Pay their Taxes, So Labor Must Do So

Panayotis,

Do you have a proof ? Btw, I noticed your comment on WCI about Nicholas Kaldor. Remember I referred you to Godley and Lavoie – they are both “Kaldorians”. You may want to check this preview of their book from Palgrave’s website

Bill, again excellent post from you on our current malaise. But I do not buy your relentless pessimism. Let me put it this way: you are married to MMT and what opportunities for the public good a free-floating non-convertible FIAT currency can provide. Although I do think this framework should be at the center of thinking about monetary arrangements, debt/deficits and fiscal policy the current arrangements within the EMU clearly does not really fit with the theory. Thus you are carried away by your bias for independent currency issuing sovereigns and tend to predict doom & gloom in the future. Sorry to say that, but in regard to the EMU you’re practically the other side of the coin of the Kenneth Rogoff currency. Unfortunately your stardom in Germany has still a way to go before outdoing the current darling and guru of the media. It’s very annoying to read almost everyday some thing along the line: “The one and only who understands the current crisis”.

So to put things into perspective. We’re talking here about the EMU. That translates into a 8.4 trillion Euro (PPP) GDP. Europe is always talking and quarreling until almost everything seems spoiled. But no rule whatsoever is written in stone here. Once the shit hits the fan things happen and then they happen fast. The ECB is the 8.4 trillion gorilla in town and before the Euro hits the iceberg, this gorilla will wake up and decide, that although somehow embarrassing he must now play with the chimpanzees in London. And there’s now way the chimpanzees will walk away not looking like fools. I think the EMU is uncharted territory but I wouldn’t write it off yet.

Ramadan,

1. The food for thought comment above, is based on national accounts manipulation if the primary deficit balance is all financed by debt which is the basis for the savings ratio in the income multiplier relevant for the deficit, after decomposing the multiplier effect.. Any thoughts on the implications? I am writting a paper on the topic dealing with debt restructuring, austerity measures and domestic debt substitution. Cabral(20010) has written also on this issue without the dynamics I am working on. For example, the feedback loop becomes more explosive!

2. The point in my comment in the WCI blog is that they were arguing across purposes as they had to agree on whether the issue was money and liquidity. I am familiar with the work of the writers you mention and the debate between circuit theorists and PostKeynesians proper. I tend to synthesize their views as I emphasize uncertainty as the reason for hoarding reserves and currency, and liquidity as a flow concept that corresponds to purchasing power required for all purposes of transactions which comes from credit.

Thank you for your comment.

Panayotis,

The government debt can be purchased by anyone – not necessarily by the external sector. Of course, since the external sector – as in the case of the US – wants to keep exporting to the US and keep accumulating Treasuries. Yes, the debt/gdp keep increasing at a rate, though not necessarily alarming. I am interested in the external sector’s purchases of other assets, which as you said induces an income drain. Will check the reference you gave. Thanks.

Ramanan,

I agree that the public debt can be purchased by anyone that wants to accumulate domestic debt. This however, for revenue constrained economies represents a problem as it causes an income drain and reduces tax income as the income from debt interest payments is taxed by other governments. The trick I designed allows me to seperate the effects and bring an extra source of feedback loop which is explosive.

Dear Stephan

I agree that ultimately all the rules and posturing will give way to a “pragmatic” solution – as the boss of the EC said they will do “whatever it takes”.

And I think from that perspective the ECB is the sleeper in the house. It actually can do something very quickly to stop this rot.

But in the long-term that “something” has to be institutionalised for the Eurozone to persist in its current form much less in an expanded form.

best wishes

bill

[anon said]

But it’s a fine line between primary “financing” (supra fiscal as per above, without purchase of national debt) and secondary market “financing” (supra CB monetary, with purchase of national debt).

The end result is effectively the same in terms of net financial assets – currency, reserves, national government liabilities PLUS (supranational liabilities issued MINUS any national liabilities purchased by the supra CB).

[/]

that’s an interesting point, but the end result is that also the caveat for this ECB/eurozone intervention to help struggling economies within the eurozone, is that the eurozone countries in receipt of the assistance will surely have no alternative but to implement the drastic cuts along IMF lines….whereas a sovereign nation running it’s own deficits doesn’t have this imposition from an outside authority. IT depends how far along the road of ‘conditional’ does eurozone help become. Once it’s clear that the

austerity measures make a bad situation worse, do they once again move the goalposts in the name of protecting the single currency.

Bill,

Can you comment on the “quantitative easing” by the ECB, please?

http://euobserver.com/19/30048

Another point to think about.

Regarding fiscal policy and austerity measures, an economist usually considers resource constraints for operations and revenue constraints for behavior that induce feedback loops. These are, however, relevant only for privacy dynamics of units that operate, behave and react in markets subject to a private domain of proprietary attributes/rights. These units react to the incentive of interest subject to competition and synergy.

There is, however, another possible orientation of impact/feedback(recovery/impression) which is derived from publicity dynamics. The relevant impact constraint for operations is sentiment and the impact constraint for behavior is emotion. The units that transact with publicity dynamics operate and behave in communities (politically) subject to a public domain of common attributes/rights. These units react(demonstrate) to the incentive of duty subject to solidarity and cooperation. The effects of sentiment and emotion represent an impact upon the resource/revenue constraints and amplify the feedback loops of privacy dynamics and vice versa.

In summary, the point is that austerity measures trigger negative feedback loops of sentiment and emotion constraints, expressed by people in strikes, demonstrations and violence etc., that defeat any positive feedback of austerity measures or fiscal consolidation and amplify in the same direction the feedback loops of privacy dynamics.

Andrew says: Can you comment on the “quantitative easing” by the ECB, please?

Have you yet seen the post “quantitative easing 101”, and a recent one on central bank operations?

Dear Anon at 10:43 pm

You said:

Overall net financial assets would be unaltered as you say, but the central bank operating factors would be different. There would be more bank reserves and less public debt.

best wishes

bill

Dear Ralph at 12:21 am

As far as I can work out the UK has very little of its public debt denominated in foreign currencies which is not the same as saying that foreigners do not hold the debt. Foreign-currency denominated public debt is a recipe for insolvency whereas who holds the debt is irrelevant.

best wishes

bill