The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

People are now dying as the deficit terrorists ramp up their attacks

Three people are dead in Athens as the people turn ugly against an even uglier ideological push against their welfare. The EMU is now facing an untenable future. Senior policy makers within the EU are now lecturing the UK about the need for harsh fiscal measures following the election. And the UK goes to the polls today and the polls are suggesting “sweeping gains” for the conservatives who are unfit to govern and will drive their economy even further backwards if elected. All of this is unnecessary. All of it a reflection of a failed ideology trying to re-assert itself. The upshot will be that the Eurozone will wallow in crisis for years to come and the rest of us are taking policy positions that will lead to the next crisis – if not a double-dip recession later this year.

Note: the UK Labour Party are also not fit to govern – which just demonstrates how damaging the neo-liberal onslaught on our polity has been over the last few decades. All political parties have started to attract conservatives who just “badge up” with Labour/Liberal/Tory/Democrat/Republican – as career moves and learn to mindlessly recite the mainstream macroeconomics dogma about deficits, public debt, and the rest of it.

As this process of selection has developed, our political parties look more and more alike and the voters have very little real difference. The contest becomes one of selecting which party is proposing the biggest budget surplus in the shortest period of time.

And the slime that makes up my profession – particularly the academic economists and those working in the international organisations like the IMF, the OECD etc – mostly provide support to this vacuous debate with their meaningless “research” papers. Maybe I should have been a geologist or something.

At least the economists were quiet for a while as the global crisis accelerated – given that their models were all shown to be wrong and of no application to anything we might call the real world. But progressively, they have been crawling out of the slime again and seeking to strut the centre stage.

I find it sad (but ironic) that as the world continues to endure the severe economic and financial crisis, that it is the countries with the least fiscal freedom that are now on the brink of collapse – those with fixed or pegged currencies and inflexible fiscal rules that lived the neo-liberal dream to the hilt – deregulated financial markets, lot of foreign-currency debt and the rest of the madness (consider Latvia – now among the poorest advanced nations as a consequence of this free market embrace).

It is also astounding that the economists who vigourously promoted the mainstream free-market anti-fiscal policy agenda are now once again lecturing nations on their policy positions and demanding they cut deficits quickly. Most of them should have been sacked at the onset of the crisis when it was clear they had no idea that it was coming and their textbooks and notes they give to their students contain no capacity to understand what has happened or what the solutions are.

It is extraordinary that their irrelevance has been forgotten and that they can once again command respect in the media as experts with something useful to say.

Anyway, after that vent – I have been examining fiscal positions for various countries today as part of another project and here is a little bit of what I know.

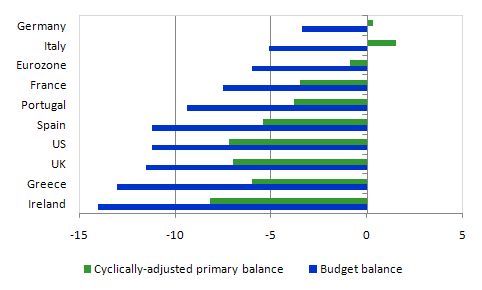

Consider the following graph which is taken from OECD data and shows the decomposition of the fiscal position for selected nations into the actual budget outcome and the cylically adjusted primary balance for 2009. The cyclically-adjusted primary balance is the estimate of the difference between government spending and taxation net of debt servicing payments which would be found if the economy was at “full capacity”.

As I explain in these blogs – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers and Structural deficits – the great con job! – the mainstream estimates of the structural deficits are always biased towards expansion. That is, the estimates suggest the discretionary fiscal stance is more expansionary than what is the reality.

Given the presence of the automatic stabilisers that move with the business cycle, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle without any change in discretionary stance. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So trying to discern the discretionary fiscal stance from just the raw budget outcome is impossible. The budget might be in deficit yet the underlying discretionary policy settings might be contractionary. The deficit then reflects the automatic stabilisers reacting to the drop in income growth.

For these reasons, economists devised the Full Employment or High Employment Budget measure. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

The estimates are fraught with measurement issues – most notably the uncertainty of computing the unobserved full employment point in the economy. As I explain in the blogs cited above, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

With that in mind the graph is even more stark. You can see that Germany and Italy were actually running contractionary discretionary fiscal positions (green bars) at the height of the global downturn (over 2009). Further, the Eurozone overall was running only the mildest expansionary position in discretionary terms. Greece’s so-called public spending binge only resulted in an expansionary position of around 6 per cent of GDP.

Given the bias in the estimates, all the green bars should be reduced if negative and increased if positive. So the degree of discretionary fiscal stimulus in Europe is in fact very moderate which explains why the recession has persisted for so long and why nations which are not sovereign are finding it hard to fund themselves.

If you think about the UK and the US, the only sovereign nations shown in this graph. Their discretionary fiscal positions are also rather moderate given the scale of the downturn they faced. This data goes a long way to explain why we are still in this mess and only crawling ever so slowly out of it, while the Eurozone heads further into crisis with a collapse of its banking system the next link in the chain of their idiocy.

Even the IMF is admitting that fiscal intervention in advanced nations has been effective over a long period across a large sample of nations. In a recent working paper – Fiscal Policy and Macroeconomic Stability: Automatic Stabilizers Work, Always and Everywhere – the researchers examine “the classic debate on the effectiveness of fiscal policy as an instrument of macroeconomic stabilization”. They note that in the current crisis, “a growing number of countries turned to fiscal policy as their primary stabilization instrument”.

Some of the reasoning is far-fetched IMF stuff but the basic results cannot be made consistent with an anti-fiscal policy line.

The aim of the research is to put “the current revival of fiscal stabilization policies in a broader perspective by revisiting the contribution of fiscal policy to macroeconomic stability in both industrial and developing economies over the last 40 years” and they study “49 industrial and developing countries for which reasonably long time series exist for fiscal data covering the general government”. So a comprehensive sample.

They find that:

First, automatic stabilizers strongly contribute to output stability regardless of the type of economy (advanced or developing), confirming the effectiveness of timely, predictable and symmetric fiscal impulses in stabilizing output … [their second result is statistically compromised – endogeneity and identification problems!] … Third, access of individual consumers to credit appears to exert a stabilizing influence on output and private consumption. A weaker contribution of credit supply to smooth cyclical fluctuations could thus increase the public’s appetite for fiscal stabilization.

They also show that in advanced economies (generally the OECD-bloc) fiscal policy seems to be countercyclical, which is a major rebuff for the mainstream macroeconomists who eschew activist fiscal policy because they claim it is pro-cylical. That is, they think that it is subject to such lags in implementation that by the time the expenditure flows private spending has recovered. Then, the political difficulties of cutting net spending back again are alleged to result in fiscal policy pushing the upswing rather than attenuating the downswing. The IMF paper doesn’t find evidence for that claim.

Does the increasing size of government make fiscal policy less effective? Not according to this research. They find:

… that more affluent economies tend to have larger government sectors – and correspondingly larger automatic stabilizers – and to conduct more countercyclical fiscal policies. This is in line with Wagner’s Law and the presumptions that these countries have better fiscal institutions – including stronger expenditure controls and tax collection capabilities – and that they are less likely to face binding credit constraints in bad times.

Of-course, for most of these nations the “credit constraints” are entirely voluntary, given their governments are sovereign in their own currencies. This suggests that if governments exploited the opportunities that accompany such sovereignty – that is, stop issuing public debt to match their net spending – that fiscal policy would be even more effective.

They also find that:

… more open economies have on average larger governments because automatic stabilizers offer insurance against external shocks … [and that] … output volatility is on average larger in countries with smaller governments, regardless of trade openness …

So fiscal policy provides a buffer against external fluctuations and smaller governments are associated with greater output variability (bigger downward swings in economic growth).

They also demonstrate that “highly indebted countries are more likely to engage in procyclical consolidations, they appear to be less actively pursuing stabilization on average” which is a testimony for how wrong-headed the neo-liberal agenda has been. The fear of public debt actually leads sovereign governments to unnecessarily implement inappropriate fiscal policy settings that worsen the economic situation in their nations.

We are seeing that now and we will see more of it as governments cower to the demands of the likes of the EU Economic and Finance Commissioner, the credit rating agencies and the Peter G. Petersons of this world. All of these voices reflect the meaningless diatribe of the deficit terrorists and should be disregarded. The reality is that their erroneous messages will be heeded to the detriment of the world economy.

The UK Times carried the story on May 2, 2010 – Can UK fight off the Greek debt monster? – and it makes you wonder whether the journalists have thought about the basics.

Like – is there anything intrinsic difference between the UK and Greece?

Like – which country issues its own currency?

Like – which country sets its own interest rate?

Like – which country floats its own exchange rate?

At least conservative mainstream economic Alan Blinder understands these basics.

In a National Public Radio interview on April 30, 2010 – Is A Debt Crisis Around The Corner For U.S.? – the presenter began with this intro:

An aid package to keep Greece from defaulting on its debt is still being hammered out. It’s expected that the Greek government, European Union officials and the International Monetary Fund will complete a rescue plan over the weekend. Many Americans worry about the size of U.S. deficits, and NPR’s John Ydstie takes a look at whether the U.S. could suffer a similar crisis.

Ok, after you scream consider the responses of the guests who included Carmen Reinhart who (with her co-author Kenneth Rogoff) continually misrepresents their research on sovereign defaults as if it applies to all sovereign debt; Robert Rubin and Alan Blinder (Princeton University; Former Vice Chairman, Federal Reserve).

Reinhart said in response to the intro:

Countries, time and time again, allow themselves to be positioned in very vulnerable situations because they think the crises are things that happens to others, not to us.

So … leading the listener into a mindset that all nations are vulnerable – but not specifying any detail to allow the listener to discern one way or another the conditions under which sovereign debt might be an issue. She was forced to admit that the US is not in any “impending” danger of default.

Then Blinder was introduced as thinking “a Greek ending to the U.S. debt drama is unlikely”:

The differences, to me, outweigh the similarities.

The interviewer clarified this by saying “there’s one really crucial difference between the U.S. and Greece, says Blinder. The U.S. has its own currency. The Greeks gave up theirs when they adopted the euro.”

Duh!

Blinder also said:

If Greece was not part of the eurozone, the drachma, which is what it was called, would have already depreciated substantially. That would be giving a boost to Greek exports and to the Greek economy.

At least at that level he understands that the “Greek debt monster” is all self-inflicted as a consequence of their decision to join the dysfunctional EMU. It is a pity that the ill-informed journalists keep filing stories claiming that the EMU disaster will spread to sovereign nations, not that they ever understand the difference between the two monetary systems. They would be better writing about flower shows!

UK options

I suppose I should say something in recognition that today the UK voters cast their votes in the national election. Like lambs to the slaughter!

Yesterday (May 5, 2010) the EU’s Economic and Monetary Affairs Commissioner released the Spring forecasts for the EU region. The forecasts are fairly grim. But the Commissioner (Olli Rehn) took the opportunity to start lecturing Britain about its fiscal position. The UK Times carried the story – Britain must cut deficit quickly, Europe warns.

According to the Commissioner, who is overseeing a major EU fiscal crisis – characterised by the EU governments not net spending enough:

The first thing for the new government to do is to agree on a convincing, ambitious programme of fiscal consolidation in order to start to reduce the very high deficit and stabilise the high debt level of the UK …. That’s by far the first and foremost challenge of the new government. I trust whatever the colour of the government, I hope it will take this measure.

These claims belong in the land of make-believe. The reality is that the next British government has to ensure that they provide increased fiscal support for its pathetically weak economy.

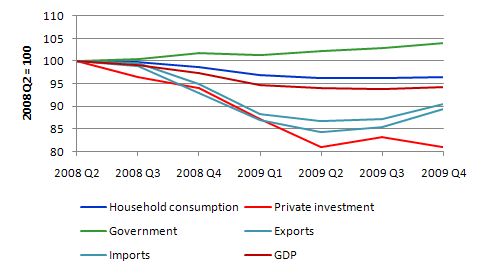

Consider the following graph which is taken from National Accounts data available from the UK Office of National Statistics. I took the main aggregate demand components, indexed them to 100 at 2008Q2 when the peak was reached and plotted them until the last quarter of 2009 (the latest available detailed data).

What you see is a disaster – a major collapse in private spending over the course of the recession. Even household consumption fell by 3.5 per cent of this period. More stark has been the near 20 per cent decline in gross fixed capital formation (that is, investment in productive capacity). The decline in net exports has been subdued even though exports dropped by 10 per cent because private spending on imports has been so weak. Overall GDP has dropped by 5.8 per cent over this period.

And the only thing that has stopped this from being a major depression has been the modest growth (up 3.9 per cent) in government spending. If you compare this result with the previous graph you will see appreciate how far the decline in tax revenue has been in the UK, which has driven the budget to its current levels.

I would also recommend you read this blog – UKs flexible labour market floats on public spending – which documents in some detail the importance of net public spending as a promoter of sustained employment and economic growth in the UK. The UK did not sustain relative strong employment growth (at least in terms of recent history) because of its Thatcher experiment or subsequent increased labour market flexibility. The evidence indicates a dominant public sector role even before the crisis.

The evidence also suggests that the scale of the fiscal stimulus in the UK has been relatively small (this is not considering the ridiculous bailouts) and that cutting back on that stimulus to satisfy the loons in the conservative press and the ratings agencies would be a very big mistake.

The manifestations of this fiscal failure (characterised by taking an excessively conservative position during the crisis) are the chronic unemployment, particularly among youth; the rising racial tension as certain ethnic groups are targetted as “taking jobs” of the others; a declining health system; and an education system that is straining under funding shortages.

So to claim that the “first and foremost challenge of the new government” is to invoke an austerity package just exemplifies how far skewed the priorities of our leaders have become over this neo-liberal period.

The actual facts that pertain to Britain are:

- The UK Government is sovereign in sterling and can never be insolvent.

- The public debt that the UK Government has accumulated as it fights the real crisis its is overseeing will never expose it to any technical danger of default.

- The same public debt is being accumulated voluntarily under the misplaced belief that the deficits have to be “financed” or rather the neo-liberal motivation that the deficits should be matched pound-for-pound by public debt issuance.

- There is very little danger of inflation occuring from demand pressures as long as the GDP growth rate is as far below capacity as it currently is and is forecasted to be over the coming 5 years.

- The ratings agencies are irrelevant when it comes to assessing government solvency.

- The British Government has as much fiscal capacity left as there are idle resources available to bring back into activity. If they want to spend more than that limit then they have to raise taxes and squeeze private spending. They are a long way from that at present.

- The UK Government could be more effective in meeting the labour market challenge by offering a minimum wage job to anyone who wants a job and currently doesn’t have one. This would represent the minimum fiscal stimulus required to generate full employment. Then they could work on improving things further with the security that everyone was in work.

The UK Government, no matter how badly managed at present, faces no solvency risk. None. Zero.

No serious policy decision considered by the British government or any sovereign government for that matter should ever include a moment’s consideration of what the ratings agencies might or might not do.

It is clear that the Government has to increase net spending to underwrite employment and finance non-government saving intentions. If it doesn’t do that the budget deficit will just keep rising anyway as a consequence of the automatic stabilisers. Private spending remains very weak in Britain and will take years to recover. Even the EU’s Spring Forecasts (noted above) are muted for Britain.

It is nonsensical for the Government to target some budget outcome. They cannot control that outcome anyway. The budget deficit outcome is what we call an endogenous event in the economy – that is, determined by the overall system. In particular the saving and investment decisions of the private sector play a big role in determining the size of the fiscal balance.

So, sadly, I suspect the election in Britain will deliver a very anti-people outcome. Maybe the damage the Tories cause will see them jettisoned from office at the following national election. And in the meantime, maybe the Labour Party will have expelled all the fiscal conservatives and developed a real plan of action to advance public purpose. Pigs might fly!

But, today – if you were a British voter – who would you vote for? The choice is a no-choice. The neo-liberal onslaught has eroded democracy.

Conclusion

Another frustrating day of reading for me. Idiocy reigns supreme.

But when you think that people are starting to die because of this ideological nonsense and that the policy positions that are directly responsible are all the result of governments voluntarily accepting unnecessary constraints which restrict their capacity to pursue public purpose and will damage their economies even further – one gets a little angry.

That is enough for today!

This blog is a beacon of rationality in a world that seems to have gone insane.

I’m a Brit and I am deeply depressed at the state of public debate in this country and what will happen over the next few months. All the main parties have embraced the “austerity” agenda while the Conservative Party seems to want to go further than the other two in slashing and burning. They have promised an “emergency budget” (full of cuts) within 50 days if they win the election. To my mind it is will named as it will undoubtedly cause an emergency.

I was actually reading that paper on the bus, and I just *knew* it would be turning up here within a day or two….Nobody can sniff an automatic stabiliser like you!

Pity the Greeks don’t have the other stabiliser – the currency – that we in Australia have grown to very much appreciate. I’m sure they will in time, however. The Euro was ill-conceived back in 1999, and the rotting fruit of that union is now pretty plain to see at its first real test. 11yrs of inconsistent policy across nations (and pumped up GDP with appalling internals) later, it’s time to put this baby to bed.

Dear Bill,

As economists we tend to base our analysis on numbers as displayed in value and quantity/quality. We forget or refuse that there is a substantial level of human feelings displayed in emotions. They are important because they allow a human or life element in the analysis and I do not mean it as a behavioral paradigm of Kahneman, Tversky, Thaler, et al. I mean it as emotional reactions that contradict feedback as prescribed by economic policy. This is not an irrational behavior but an emotional response individually and collectively that can defeat the conclusions of our analysis. Is a form of contradiction that is left out of our models. When people scream (as in the demonstrations I attended) policies fail. Economists and politicians take notice!

Besides demonstrating Greeks find the time to joke in breaks. One joke takes place in Mykonos world central for tax evaders who in gatherings at local bars shout together ” You do not dare confiscate our Cayenne (car), Ohlin Rhen,Ohlin Rhen (the Eu commissioner)”!

You could always move to Norway where there is plenty of money for fiscal stimulus. One sane country in an insane world…

One out, one in…

“Hungary: The new government wants to increase the deficit”.

But they are not a member of Euro.

http://translate.googleusercontent.com/translate_c?hl=en&ie=UTF-8&sl=pl&tl=en&u=http://wyborcza.biz/biznes/1,100896,7849862,Wegry__Nowy_rzad_chce_zwiekszyc_deficyt.html&prev=_t&rurl=translate.google.com.au&twu=1&usg=ALkJrhhQwj2hTCw3pXi1D9AUmDYyWBXdEw

Hope the translation is readable.

The second phase of the financial markets meltdown may force more governments to follow.

THe current crisis is bringing out the conflict between markets that promote competition in pursuit of proprietary private interest and communities that promote solidarity in pursuit of common public duty. The markets are beginning to capitulate to people expressing their opposition to austerity measures and are pressuring asset prices as they believe that theses policies willl fail. People power that even markets listen to and respect it!

Ernst Fehr on fairness:

Ernst Fehr: How I found what’s wrong with economics

im curious bill, and forgive me if this question borders on the bleeding obvious,

but isnt the greek NCB responsible for currency issue, and if greek sovereign debt is denominated in euro’s, then whats to stop the greek government from running large deficits and paying off large swaiths of sovereign debt all in euros , and simply ignore eu regulations and daring the eu to take action if they have the guts to do so.

perhaps they should play a game of chicken with the regulators. and simply keep spending in euros, to see if the eu authorities blink.

after all its legal framework we are talking about, and sometimes they arnt worth the paper they are written on.

Dear Tom,

You are right about FERH, he EVEN (fair!) has the right NAME! As my name with economics as you know!

In my own work, I distinguish between a) behavior based on reason, as decision based on rationality and praxis based on rule and b) behavior on ethics, as decision based on fairness and praxis based on equity. Reasonable behavior is exercised by shelf units in the private domain and markets and ethical behavior is exercised by civic units in the public domain and communities. Units are a joint occurence of both with relative intensity depending on the relative intensity of the orientation of the situation coincidence. Any thoughts?

Dear Takis, what you say squares with what evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson observes about the difference between individuals operating in small groups and individuals operating in large groups like societies. Competition yields advantage in small groups, while cooperation yields advantage in large groups.

“but isnt the greek NCB responsible for currency issue, and if greek sovereign debt is denominated in euro’s, then whats to stop the greek government from running large deficits and paying off large swaiths of sovereign debt all in euros , and simply ignore eu regulations and daring the eu to take action if they have the guts to do so.”

This question was raised and answers in several previous posts. Essentially, the Greek government’s situation is akin to that of a US state. But I’m a partisan of no stoned unturned when it comes to that, and I wouldn’t mind delving a little more into this issue. Here’s how the US gov spends as per WM:

1- The Treasury sells $100 billion of treasury securities.

2- Paying for the new securities reduces member bank balances held at the Fed by $100 billion.

3- And our holdings of treasury securities increase by $100 billion.

4- The Treasury spends the $100 billion it got from selling us the $100 billion of new treasury securities.

5- This increases member bank balances at the Fed by $100 billion.

Recap:

* Bank balances are back where they started from.

* Our holdings of treasury securities, which are financial assets and saving, have increased by $100 billion.

Now, how about the Greek government, exactly? 1- is preserved. The ECB (via the NCBs) is, as per Euro legislation the “fiscal agent” of the state, so you’d think that 2- and 3- also applies. 4- is kinda obvious, and 5- is a result thereof. Where’s the difference?

The difference has to be that the Greek government does not keep an account at the ECB but at a private bank, so 1- does not cause 2-, an increase in bank reserves. This needs to be clarified, IMHO.