The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Bailouts will not save the Eurozone

We are back onto Greece again today as the crisis deepens. Overnight Spain is appearing to be under bond market pressure and the Germans are calling for even harsher fiscal rules to be applied to keep member states “solvent”. The point is that none of the remedies being proposed will ultimately work. What is needed in the Eurozone is a major boost to aggregate demand. However, the policy direction is to further undermine spending in the member economies as austerity measures are being imposed throughout. This foolish reverence of the Stability and Growth Pact will worsen things. The problem in the EMU is that the basic design of its monetary system is flawed and the accompanying fiscal rules only accentuate those design flaws. None of the remedies being proposed by Euro leaders will work and the bailouts will not save the Eurozone. It has to fundamentally redesign its system or disband.

Paul Krugman’s recent blog – Default, Devaluation, Or What? – published May 4, 2010 raises some interesting questions about the current situation in the Eurozone.

Krugman notes the obvious – that the EMU bailout for Greece will fail:

Consider what Greece would get if it simply stopped paying any interest or principal on its debt. All it would have to do then is run a zero primary deficit – taking in as much in taxes as it spends on things other than interest on its debt. But here’s the thing: Greece is currently running a huge primary deficit – 8.5 percent of GDP in 2009. So even a complete debt default wouldn’t save Greece from the necessity of savage fiscal austerity. It follows, then, that a debt restructuring wouldn’t help all that much – not unless you believe that getting forgiveness on much of Greece’s existing debt would make it possible to take on substantial new debt, which doesn’t seem very likely.

This statement is only partially true. A complete debt default will not save Greece now under current institutional arrangements associated with its EMU membership, given its need to run on-going deficits.

However, default (or renegotiation of its Euro obligations into drachma) would help if it abandoned its membership of the EMU. Ultimately the way the events are unfolding the EMU will not be able to maintain its integrity without significant changes.

But it is true that under current institutional arrangements the bailouts will not work. They will have a short-term palliative impact only on the bond markets but cannot overcome the intrinsic dysfunction in the Eurozone structure which has led to this crisis.

The austerity packages that will accompany the bailouts will also make things worse.

Even the mainstream macroeconomists such as Charles Wyplosz realise the situation is past the point of no return. He wrote on May 3, 2010 that:

Eurozone members, the IMF, and the ECB have announced significant commitments to assist debt-laden Greece. This column outlines a dark scenario in which the plan fails and contagion spreads, necessitating further assistance to other indebted Eurozone governments. That could risk high inflation or debt problems for the entire Eurozone.

The weekend announcement of a new plan for Greece, topped by the ECB decision to accept low-grade Greek debt instruments, is commonly seen as a European success. Quite to the contrary, we may have just planted the seeds of an unraveling of the monetary union.

He emphatically concludes that the bailout “plan will not work”. Why? Because the scale of adjustment that is being imposed on Greece – reducing its “deficit by 11% of GDP in three years” is not a realistic goal.

This point was always obvious. The austerity plan that is being imposed on Greece will increase the budget deficit not reduce it.

Some commentators have argued that because there is so much tax evasion in Greece the automatic stabilisers are much weaker than in other more “tax-compliant” economies. So a sharp cut-back in government spending may induce a deeper recession but the loss in tax revenue will be muted. The data doesn’t suggest that proposition to be true.

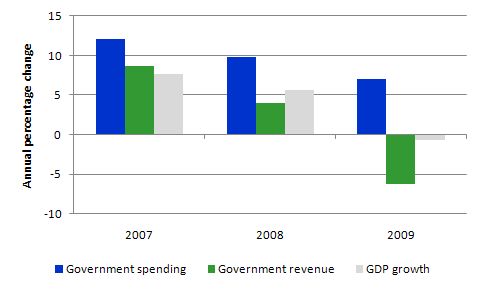

The following graph shows the annual percentage change in Greek government spending, revenue and overall GDP growth for the years 2007 to 2009. The data is available from Eurostat. The graph tells us two things.

First, the Greek government cut back spending when it should have increased it as the crisis worsened. Trying to stick within the Maastricht straitjacket has worsened their crisis and a “free” sovereign nation would have been able to mount a more concerted attack on the private spending collapse. Most of the spending collapse has come from private capital formation and exports. Both components of aggregate demand plunged in 2009 (Investment down around 12 per cent and exports down a staggering 15 per cent).

Second, tax revenue in Greece is highly cyclical.

So I expect the budget deficits to worsen as the austerity packages are implemented in Greece.

Wyplosz notes that the austerity plan “will provoke a profound recession that will deepen the deficit” and, given the way the EMU monetary system is structured, the Greek government will have to keep placing debt in the private bond markets. This need is what has brought the Eurozone to this point. It is going to get worse.

So how can Greece possibly satisfy the demands on it, given it is hamstrung by the internally inconsistent EMU Treaty rules? Answer: they cannot!

Within the logic of the EMU, there are only two outcomes: (a) The EU governments keep tipping bailout funds into Greece and then Spain and onto Portugal – without resolving the basic dysfunction in their monetary system; or (b) Greece will have to default.

If you examine the “refinancing” schedule facing Greece given the maturity dates of its debt and the fact that it will run on-going and probably increasing deficits for years to come, you quickly conclude that the financing conditions facing the government will worsen as time goes by.

Wyplosz says that the markets “will further raise the interest that they request to roll over the maturing debt or simply refuse to refinance the debt”. Then what happens?

Greece becomes dependent on the IMF or the EU for further finance in Euros despite the fact that a legal challenge under Article 125 of the European Treaty is almost certain. The bailouts challenge the basic rules that are being imposed on Greece.

The so-called “no bailout rule” Article 125 says:

1. The Union shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of any Member State, without prejudice to mutual financial guarantees for the joint execution of a specific project. A Member State shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of another Member State, without prejudice to mutual financial guarantees for the joint execution of a specific project …

Given the bailouts are seemingly inconsistent with Article 125, why impose one of the Treaty rules yet violate another, especially when the rule being enforced will have severe consequences for economic growth and living standards? This inconsistency is further evidence that the EMU is dysfunctional and should be disbanded.

In recent days, the news is creeping out that Spain is lining up to be the next victim of this absurdity. Given the larger size of the Spanish economy, the implied bailouts will be much larger than anything contemplated for Greece.

As Wyplosz notes:

What has been offered to Greece cannot be refused to other Eurozone governments. So, one more time, a (dwindling) group of deficit-stricken countries will have to provide money to increasingly large debtors. In fact, this process means that ultimately there is no national debt anymore, at least for the next few years. In effect, in the market eyes, there will then be just one Eurozone debt. Could markets run on all Eurozone public debts?

This crisis is 100 percent the result of the way the EMU structured its monetary system. None of this is happening in the sovereign nations. Japan has been consistently running significant deficits and adding to its public debt ratio for years. It certainly has problems but they are not of a solvency or financial nature. They face the challenge of promoting real growth and job creation. The Japanese government does not face insolvency.

Krugman says that:

… the only way to seriously reduce Greek pain would be to find a way to limit the costs of fiscal austerity to the Greek economy. And debt restructuring wouldn’t do that. Devaluation would, if you could pull it off.

So devaluation of the Euro against the other major currencies may stimulate net exports. For Greece, export revenue (shipping and tourism) fell sharply during the crisis. But overall, the majority of the EMU trade is within the Eurozone and so a devaluation is unlikely to have a large enough effect.

Further, while the devaluation was taking time to work (there are long and uncertain lags in trade responding to terms of trade changes) economic growth would have to be supported with on-going public deficits which are under attack within the EMU as a result of their SGP criteria.

A devaluation accompanied by a major fiscal initiative at the Eurozone level may help somewhat. That is, if the ECB, for example, agreed to a Euro per capita transfer to each nation of x billion Euro (as a one-off fiscal support strategy) this would ease the borrowing constraints and stimulate each private economy. That might help.

However, the explicit ideological choice not to include any fiscal redistribution system within the design of the currency union suggests that the ECB will never consider such a move.

Further, it would only temporarily stave off the crisis. The basis of the crisis is not the collapse in aggregate demand that has occurred around the world – that has triggered the crisis. The basis of the crisis is in the very design of the Eurozone monetary system. The national governments are unable to respond to a major collapse in demand because of the Treaty rules.

So temporary bailouts will ultimately fail. The solution is to abandon the currency union or cede fiscal authority to a Eurozone government and not constrain that government with any irrational fiscal rules.

Wyplosz thinks that an alternative to the bailouts is “debt monetisation”. He says that:

The Greek debt is about one sixth of the ECB monetary base, already bloated after one year of credit easing. Absorbing part of this debt is doable. In fact, it is being done. The ECB has already on its book a lot of Greek debt as collateral for its lending operations. Having just accepted to continue accumulating more, even though its previous rule would have forbidden doing so after the latest rating downgrades, it would be surprising that much of the debt, now sub-investment grade, does not end up on the book of the ECB.

This would be a sensible option for the ECB to take. They are not financially constrained and can provide the Greek government with sufficient Euros to allow it to stimulate economic growth and resolve the crisis the sensible way. The ECB has bought Greek government debt via repurchase agreements with other banks (including the national central banks in the system). So they don’t technically own these assets. But if the Greek government is forced to default, the loss would be the ECBs anyway and they would face no financial constraints in bearing that loss.

Wyplosz, however, claims that if the ECB took this path then:

… you have the seeds of very, very high inflation.

Well only if the EMU approached capacity saturation and no further economic growth was possible. They might introduce guidelines on government spending to ensure it stimulated real growth rather than built statues of failed leaders! But there is no inflation risk in the Eurozone at present – quite the opposite – the risk of deflation is endemic.

Whatever, none of these proposed remedies will solve the basic design flaws in the monetary union.

To review the arguments I have made against the effectiveness of the common currency and the options facing the individual member states, the following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

- EMU posturing provides no durable solution

The beginning of defaults …?

Bloomberg News carried the story overnight that – Merkel’s Coalition Calls for EU ‘Orderly’ Defaults – published May 4, 2010. This is the first sign that the EMU bosses are preparing for a sovereign default within their system.

The Report says that German Chancellor Angela Merkel appeared on ARD television on May 3, 2010 calling for a process which would allow:

… the ‘orderly’ default of euro-region member states burdened with debt to avoid a repeat of the Greek fiscal crisis … [which] … would ensure that creditors participate in any future rescue …

According to the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, the Germans are seeking “the possibility of a restructuring procedure in the event of looming insolvency that helps prevent systemic contagion risks”.

They also want tighter rules and monitoring of deficits in the EMU to prevent a similar crisis from happening again.

So you realise that they are so caught up in their own rhetoric that they cannot see inside their system and view the rotten core. The same logic that led to the imposition of the fiscal rules in the first place and the failure to include appropriate fiscal redistribution mechanisms to cope with asymmetric shocks is still at work.

They now think that a future crisis will be prevented if they tighten the SGP criteria even further. However, automatic stabilisers do not obey self-imposed fiscal rules. Budget deficits will break the revised (tighter) fiscal thresholds just as they have broken the current limits.

Budget deficits are endogenous because they are significantly driven by private spending. This is not to say that the discretionary element is not unimportant. It clearly is. But when I say the budget outcome is endogenous I am saying that the government cannot with any certainty predict what the outcome will be – ultimately private saving desires will drive the outcome.

But you get the impression from this rhetoric that the process of default is beginning and the so-called haircuts are almost inevitable.

Idiocy …

After I considered these offerings I read the latest tripe from Nial Ferguson who has revealed himself during this crisis to be a self-promoting ignoramus – at least when it comes to saying sensible things about monetary systems. But anything to sell a book I suppose.

The Financial Post carried a Q&A session with Ferguson this week (Published May 1, 2010). The introduction revealed that the journalist also hasn’t a clue. Accordingly:

Niall Ferguson’s resumé could put you to sleep. He’s a senior fellow here, a professor of this or that there. But despite hanging out with the elbow-patch crowd, this Scottish intellectual and author smoothly blends history, finance and politics all into one understandable package.

The only correct statement is that he puts one to sleep. Further, no academics wear tweed jackets with elbow patches much these days.

But a more correct statement would be that he blends a distorted account of history and a flagrantly ill-conceived view of how monetary systems operate with an ideological disposition to right-wing politics to interact with his readers/listeners at the level of ignorance and emotion – with the ultimate aim to sell his book by scaring the bejesus out of everyone.

Advancing one’s own agenda by fear is an act of terrorism.

Anyway, in this interview he is commenting the UK economic situation as input into the election campaign. This is what he said about Greece and the UK:

The situation of the United Kingdom in fiscal terms is in fact worse than the situation of Greece … The trajectory of U.K. public debt over the next 30 years, absent a major change of policy, will take it to a mind-blowing 500% of GDP, which is about 100 percentage points worse than Greece. If Britain had done what many right-thinking people thought it should do and joined the euro, the situation of Britain would be worse than that of Greece today. The only reason that Britain isn’t an honourary member of the PIIGS club, along with Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain, is that it stayed outside the eurozone and therefore reserves the right to debase the currency as an exit strategy … Britain has a massive fiscal crisis that is just about to break … The situation is so unpromising that I would anticipate the International Monetary Fund having to come into Britain as it did in 1976.

The reference to the IMF intervention in 1976 epitomises the intellectual dishonesty that permeates Ferguson’s work and public statements.

The IMF Crisis for Britain covered the period from October to December 1976 although it had its origins in 1974 after the OPEC oil shocks in 1972 and 1973. The actual IMF loan was in December 1976 to stave off a collapsing sterling. The available documents show that the British government had already decided to implement the reforms that were later attributed as “loan conditions”.

To understand the nature of the intervention it is important to realise this occurred at the cusp of the Keynesian-Monetarist paradigm struggle as the latter was gaining ascendancy among policy makers and the old Keynesian full employment paradigm was being abandoned. This period marked the beginning of the neo-liberal dominance.

The government at the time also succumbed to the poor advice of its policy advisors – to wit, that deficits would “crowd out” private spending and that Ricardian Equivalence was operative and would kill economic growth. They began to articulate what it now known as the supply-side agenda that is characteristic of the neo-liberal period. That is, it is based on the erroneous belief that demand management (via variations in discretionary net public spending) is futile and will only generate inflation. Alternatively, deregulation and tight fiscal policy is the way to stimulate entrepreneurship and economic growth.

The British government of the day fell for this nonsense and in doing so were exposed to the logic of an IMF intervention, which is also part of the “supply-side” package.

So the pressure for an IMF intervention was being pushed heavily by the growing Monetarist lobby around the world.

But more importantly, the sterling crisis occurred because Britain was still running a fixed-but-adjustable exchange rate peg with limited capital mobility. So it was a currency crisis brought on by a failure of the British government to fully float its currency. The drain on its foreign currency holdings was inevitable under these arrangements.

Further the Bank of England had to increase interest rates to maintain the currency peg. This damaged the domestic economy which then pushed the budget further into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

The so-called government solvency crisis arose because the government refused to float the sterling and abandon its gold-standard rules which forced it to match its net spending with debt placements in the bond markets. The growing influence of monetarism also prevented the UK government from pursuing the opportunities available to them as a sovereign government once the Bretton Woods system had collapsed in 1971.

Many governments hung on to vestiges of the convertible currency system usually by running dirty floats (or managed pegs).

The point is that Ferguson would know this. Whether he understands the significance of it is another matter. But based on his public statements he either doesn’t understand it (ignorance) or does understand it and knows his readership doesn’t and decides to deceive for ideological gain (dishonesty). Either way he doesn’t come out of it well.

The fact is that the UK government faces no solvency risk. There is no currency crisis emerging because the sterling is floating and the Bank of England does not have to shed foreign reserves in its defence.

If the currency continues to depreciate then the terms of trade will continue to improve and net exports will benefit. The on-going deficits will also continue to support some semblance of growth while private investors regain confidence.

As noted above, Greece is stuck in a monetary system that allows it no effective space to manage their own economy and thus grow their way out of the crisis. The UK is totally sovereign (unlike 1976) and can continue to use budget deficits to support growth.

Economic growth is the way that these crises are resolved. Pursuing austerity worsens them.

Ferguson then went on to talk about global politics. He claimed that the President of the US “is no longer indisputably the most powerful man in the world. There is a sense he has to deal with his Chinese counterpart as an equal”. Why? (although who cares!):

Diplomatically, because of the financial interrelationship between the United States and China, the President cannot treat his Chinese counterpart anything other than an equal.

This is just a replay of the myth that the Chinese government among other foreign governments are financing the US deficit and if it sells its holdings of US dollars and/or its US Treasury bills then crisis will worsen and the US government will face rising yields on its debt and eventually the dollar will collapse.

There is no truth in any of these fears. China can only get access to US dollars by running a current account surplus – that is, shipping more stuff to the US than the US ships to them (with allowance for the invisibles on the current account). The accounting for these transactions are straightforward. The US banks representing the Chinese trading firms see rising account balances to the credit of their clients.

If the client then buys US government bonds, the client’s bank transfers the funds to the Federal Reserve bank “Treasury Account”. So the funds move from one account to another. End of story. When the Treasury retires or services the debt, reversals of these accounting operations occur.

The important point is that the US government issues and spends the US dollar. No-one else has this capacity. Further the Treasury bonds that the government issued are bought by whoever with the funds that the US government has spent in the past.

There are no constraints on US government spending imposed by the “nationality” of the purchaser of its debt.

I imagine Ferguson doesn’t understand these issues.

Conclusion

The EMU is entering the next phase of the crisis which will further expose its dysfunctional structure. The bailouts, the IMF intervention and all the talk about orderly defaults cannot overcome this basic design flaw.

The financial markets can drive the Eurozone into the ground – first Greece, then Spain, then Portugal then …. – and the current logic of offering bailouts will not be able to forestall this leapfrogging crisis.

The EMU bosses will have to eventually understand that they have to make fundamental changes to the design of their system or disband it. The Greek government should realise that it is in their best interests to leave the system immediately and start regaining control of their own affairs.

That is enough for today!

How can you go against the people? When they talk they scream and watch out! Markets of speculators against communities of citizens? I say communities rule at the end when citizens say enough is enough!

Regarding this excellent article, only a comment. The tax evasion issue will not dumpen the fall in tax revenue as those who did not report their income are operating in the informal sector of the economy. However, the austerity measures and the rise in VAT and other sales taxes will increase the incentive to tax evade by both sellers and buyers and service providers.

Ferguson: “The trajectory of U.K. public debt over the next 30 years, absent a major change of policy, will take it to a mind-blowing 500% of GDP, which is about 100 percentage points worse than Greece.”

Yeah, and the growth of land by silt deposit at the mouth of the Mississippi River should have connected Louisiana to the Yucatan by now. {I would say, grin, if it wasn’t so sad.}

Rioting in the streets. Molotov cocktails. Bank burned, Three dead. (link)

As Takis, implies, this is quickly getting very real. Austerity isn’t going down well. It’s being perceived as financial looting. I would expect that politicians around the world, and certainly in the rest of Europe, are taking note of what can happen when social unrest breaks out due to policy failures that lead to market failure. We may be discovering that the system is not economically self-correctlng, but socially and politically self-reorganizing.

Tom Hickey: “Rioting in the streets. Molotov cocktails. Bank burned, Three dead.”

And the possibility, nay, the probability of this was predictable. In the U. S. we talk about depraved indifference to human life.

Ferguson: “If Britain had done what many right-thinking people thought it should do and joined the euro, the situation of Britain would be worse than that of Greece today.”

Talk about a self-refuting sentence! 😉

“The ECB has bought Greek government debt via repurchase agreements with other banks (including the national central banks in the system).”

Could someone give me some more details on how this works? Is there a medium of exchange involved, or is it all just promises? Thanks!

What are the chances the euro becomes the way for the rich to settle balance of payments and the lower and middle class in each individual country gets a local currency that constantly devalues?

Fed Up:

The only way that can happen is if they start minting Euros using precious metals – if the country’s citizens can pay their taxes with their own currency – who would need/want/care about a Euro?

Yesterday, May 4th (US) PBS Newshour journalist Margaret Warner interviewed Fred Bergsten, director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. (http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/europe/jan-june10/euro2_05-04.html) Bergsten was on to warn among other things that the U.S. faces the same problems 10 years down the road. At the end of the interview Warner noted that the U.S. is different from Greece in that it is able to print its own currency (“Bailout for Greece Raises Stability Concerns Across Europe, U.S. | PBS NewsHour | May 4, 2010 | PBS,” n.d.).

I had hoped she would pull on that thread, but no luck.

“On any reasonable projection of the U.S. outlook, our numbers in 10 to 15 years will look about as bad as Greece’s do today. That’s a big warning sign for us. We have got time to get our house in order. There is plenty of time to do it. We have got a much stronger underlying economy.

But, if markets start focusing on those variables, it could be very severe for our own credit ratings, our own market outlook. And the fairly easy situation we have now in funding our debt and deficits could go the other way, and that could be a big problem for the United States.

MARGARET WARNER: So, despite the fact that we, unlike Greece, can print our own currency, still a cautionary tale.

FRED BERGSTEN: That is…

MARGARET WARNER: Fred Bergsten, thank you so much.

FRED BERGSTEN: Good to talk.”

Bailout for Greece Raises Stability Concerns Across Europe, U.S. | PBS NewsHour | May 4, 2010 | PBS. (n.d.). . Retrieved May 6, 2010, from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/europe/jan-june10/euro2_05-04.html

With respect to the Chinese role, they possess claims on others in the form of currency. Whether they acquired those claims by shipping out goods in excess of their consumption, or whether they invaded the US and robbed the Fed, makes little future difference. We have to honor their claims, and even if the value of those claims collapses during their redemption. So, debt seems to be debt, and future economic production on our part (or loss of relative consumption) will be needed in some form to resolve it.

Burk

Of course the US will honour its claim to China by crediting China’s Reserve account at the Fed with the amount of bonds/bills that they are redeeming. That is the only thing that the US is obliged to do. It does not have have to offer gold or anything. The only way for the Chinese to get rid of their US dollars is to spend them or give them away. If they spend them in the US, the US congress has the ultimate veto (remember China’s attempt to buy the oil producers a few years ago?).

So there is a huge difference between a claim acquired by shipping out goods in excess of consumption, and invasion and sacking of the Fed/Treasury.

nealb: ” If they spend them in the US, the US congress has the ultimate veto (remember China’s attempt to buy the oil producers a few years ago?).”

What makes then the Chinese shipping their goods and services in exchange for US dollars when they know they won’t be able to use these $$$ for every thing they would like to?

rvm, so they will not ship them and the issue is solved, correct?

It is their decision to ship or not to ship and where. Why do you want to influence it?

Sergei, I am just curious why they (the Chinese) make such stupid decision – exchanging real things for paper?

I placed this question before and Bill Mitchell answered:

“It is always to build a portfolio of financial assets in the currency of the nation that is enjoying the excess of imports over exports.

Why would a nation want to do this? For many reasons mostly related to positioning itself in world trade.

The reason our cards are valuable is because at some later date they can be exchanged for net goods and services that we produce which the next door neighbours may enjoy – in the STMs – our labour. They can make real claims on our resources if they have financial assets denominated in our currency.”

It was still not very clear for me why the Chinese would continue to do this trade especially if they know well that when they decide to make real claims on US resources the US government can just say: ”Sorry it is not for sale, thank you.”

So a pen friend of mine with a handle he uses here and on another site – “alienated” – responded this:

“Typically, a government will allow the purchase of goods and services (current output), but will block foreigners’ attempts to buy up companies, plant, resources, property rights (e.g. mining rights), etc. The government places some restrictions on domestic citizens also when it forbids certain trade in goods and services, but it doesn’t usually block their purchase of real assets. Whether these restrictions work comes down to the government’s capacity to enforce its rules.

But this observation doesn’t negate Mitchell’s point. China is trying to position itself in world trade. In particular, the build-up of dollar reserves gives China the capacity to maintain its peg with the US dollar. If it ever feels the need to support its own exchange rate, it has plenty of dollars that it can use to buy up yuan. In the meantime, sitting on dollar reserves or converting them to US bonds keeps the demand for US dollars strong relative to the yuan, and the exchange rate favorable for trade.

But, of course, whether this is in the interests of China’s general population, as opposed to its elites, is a different matter. The policy choice to build up reserves of USD by running a large trade surplus is a decision to deprive Chinese citizens of real goods and services. I think from the perspective of the general population in China, it would be preferable for the government to float its currency and shift to domestic income growth to the extent that the float results in a reduction in the trade surplus.

“Yes but US government will just say: Sorry it’s not for sale, thank you.

Why do they continue buying US bonds? – maybe China will be still satisfied to be able to buy even less important US assets.”(this was part of my questions to alienated)

Ultimately, the only ways China (or other holders of excess US dollars) can rid themselves of the dollars (assuming they want to) is to:

(i) buy US bonds;

(ii) import more goods and services from the US;

(iii) use brute force to “change the US government’s mind” on asset sales.

Barring a loss of US military supremacy, option (ii) is the only one that potentially holds ramifications for future US living standards. If and when China demand more real goods and services from the US than they give up in exchange, this may result in a reduction in US living standards. I say “may” because at the moment there is enormous excess capacity and underemployment in the US economy, so it would be feasible for the US to respond to China’s increased demand for US exports by expanding export production without cutting back other production; i.e. the higher demand from China could be met with an increase in US output and employment without necessarily requiring a reduction in US consumption levels. If at some point in the future the US is operating at full employment and full capacity along with a trade deficit, then a shift in Chinese trade behavior towards buying more US goods and services would require a reduction in domestic consumption; i.e. there would need to be a shift in US production from domestic to export goods and services.

But I wouldn’t overstate the likelihood of the Chinese suddenly making a dramatic shift towards a trade deficit and rushing to rid themselves of US dollars. The elites, by using the dollars to buy US bonds, essentially become the recipients of corporate welfare in the form of a risk-free interest payment. In any case, large changes in trade patterns tend to occur gradually, not suddenly. There is usually time to adjust. And, as mentioned, it is not as if the US economy is exactly stretched to the seams at the moment in terms of utilization of productive capacity and labor resources.

One point that might not be readily apparent is why the US elites are willing to go along with China’s trade surplus and the corporate welfare that accrues to Chinese holders of US bonds. The main reason is that the US elites also benefit from trade between the two nations. Often the exports from China into the US are intermediate goods that are then used as inputs into US-located production. The “trade” is often between two parts of the same multinational corporation. By locating the production of the intermediate goods in China where wages are lower than in the US, the cost of producing the multinational’s final output is reduced. To the extent this cost reduction is not passed on to the final consumer, the multinational’s profit margin is increased. Since multinationals generally operate under oligopolistic conditions, they are price makers (not price takers) and the profit margins can be considerable.

So China’s trade surplus results not only in a build-up of US dollars in Chinese hands, but also higher profits to US and other owners of multinationals. Gains from trade go to the Chinese and non-Chinese elite alike; that is, the global elite. The losers in the process are any Chinese and non-Chinese workers (and their dependents) who suffer reductions in wages and living standards as a result of the trade. Free trade in this instance, and in many other instances, serves as a mechanism for playing off one country’s workers against another.

From capital’s perspective, unemployment in the US as a result of the trade process is the fault of US workers for refusing to work for Chinese wages. Capital will use the lower wages in China, and unemployment in the US, to try to drive down wages in the US. At the same time, capital will do everything in its power to prevent or slow wage increases in China. This is why US and other non-Chinese multinationals and corporate lobbies (chambers of commerce, etc.) strongly oppose any improvements in Chinese pay and conditions. It is also partly why non-Chinese elites, including US elites, are happy for China’s repressive regime to remain intact. Chinese workers face a much tougher battle in winning wage increases because of this repression and the often brutal treatment of collective attempts by workers to improve their working and living conditions.

From the perspective of workers, however, the fault is with workers’ failure to act in their collective interests to improve pay and conditions for workers in all countries. Globally, a reduction in wages in any country is a loss for workers of all countries, because it provides further potential for capital flight and the pushing down of wages in all countries. Domestically, a reduction in wages of one group of workers (e.g. minimum wage workers) is a loss for all workers in that country and globally. Capitalists understand this, and that is why they are relentless in resisting wage increases, minimum wages, more generous unemployment benefits, firing restrictions, worker entitlements and legal protections, and full-employment policies. By the same token, MMT suggests – in contrast to the perspective of Trotskyists and other internationalists – that an increase in wages for workers in one country can be of benefit for workers of other countries if the general population applies sufficient pressure on its fiat-currency issuing government to use the full fiscal capacity at its disposal to deliver full employment irrespective of what capital decides to do in response to the wage increase. This does not mean workers shouldn’t push for international agreements on minimum employment and wage standards. They can use these strategies as a mechanism to raise wages everywhere just as capital uses free trade as a mechanism to lower wages everywhere. But MMT indicates that the general population can do a lot to improve its own lot even through domestic action.”

I like alienated’s post pretty much. Don’t you?

I would only slightly disagree with alienated’s post on the following: “If and when China demand more real goods and services from the US than they give up in exchange, this may result in a reduction in US living standards”.

Lets get real (so to speak). Real goods are one thing, but real services are another – services supply is more flexible, requires different composition of labor, is highly dependent on education, than real goods supply It seems to be more difficult to consolidate services and control supply (cartels) – although intellectual property laws are looking like a pretty good tool for that.

A while ago, Bill had mentioned that he was considering taking up the argument that manufacturing is not required for a country to maintain high wages/living standards. Those that maintain that we need manufacturing in the US to get incomes higher are kind of like the old physiocrats that argued agriculture was the source of value. (Now, having said that, countries do keep strategic reserves of agricultural products and a major component of US exports is agriculture). I do think the manufacturing/service discussion would be interesting – although it is off-topic from our MMT focus.

I would like to second pebird’s request for a blog post about the necessity of manufacturing in a modern economy. Also pebird, really nice comparison with the physiocrats’ insistence on Agriculture as the only true source of value. It’s nice to see some economic history references popping up every once in a while.

pebird’s post said:

“Fed Up:

The only way that can happen is if they start minting Euros using precious metals – if the country’s citizens can pay their taxes with their own currency – who would need/want/care about a Euro?”

because the local currency is devaluing faster than the Euro. I don’t believe taxes are the only reason for demand of a currency.

rvm,

You obviously know a lot more about this stuff than I do, but I found this article by Henry Liu entitled “Why China must buy US Treasuries with her Trade Surplus Dollars,” to be pretty interesting:

http://www.henryckliu.com/page215.html

According to Mr. Liu, the reason China has to purchase U.S. Treasuries is “dollar hegemony.” That is, because many major commodities, most notably oil, are denominated in dollars China has to export more goods and services to the U.S. than it imports to get the dollars it needs to control its own independent developmental path. At least that was my understanding of the article. It’s a bit wordy and a little complicated (for me) at times, but I think it goes at least part of the way towards answering your question of why the Chinese should exchange real goods and services for pieces of paper. If you have the time to read the article I’d be interested in hearing your opinion.

You implicitly assume that China wants to have US assets but this is a false assumption. There are many points why China wants to accumulate USD but obviously not all of them focus on the USA.

Dollar is a universally accepted currency thanks to its global reserve status. This means that China virtually can buy any asset in any country using its dollar reserves. And when I say “any country” I first of all mean “any emerging country” which in times of economic stress and otherwise is normally hungry for USD. Especially if they can get USD at slightly lower prices than in London. And what can China buy in such countries? The most valuable stuff on this planet: real and limited natural resources in exchange for worthless electronic records.

So all US citizen can relax here. China is not going to declare a war on US to get hold of all empty houses across the country 🙂

NKlein1553,

I am far away of knowing more about this stuff, and that’s why I and you are here, on billy blog, where the smart people are 🙂 -to hear their opinions on matters which interests us.

As far as I can understand the question regarding China’s external surplus is related also to the status of the USD as the world’s reserve currency.

I asked Warren Mosler about his opinion regarding that special status of USD. What does it mean? He replied that in his opinion it was a nonsense – each sovereign country issues and floats its own currency so they don’t care about USD. Well I was a little sleep deprived at that time – during the MMT counter conference in DC last week – so I forgot to ask him a second question – why then the world oil prices are in USD?

@rvm – I don’t think that the the question of the USD being a world reserve currency really matters; Chinese elites would still get the global power they crave even if they were accumulating euros rather than dollars. From the Chinese perspective, the decision to hold dollars rather than euros may have something to do with the USD reserve currency status, but not the decision to hold foreign reserves.

Sergei has the right of it – by accumulating foreign currency reserves (of whatever sort) China gets real power though their ability to make claims on real assets all over the world. Oil in South America, iron ore in Australia, Agricultural land (water rights, really) in Australia and Africa. This is real political power without the need to compete with America’s insane military spending. As long as Chinese elites can manage discontent in their domestic population (ie as long as there are still dirt poor peasants willing to migrate to cities) they are going to keep using a good chunk of their economic growth to provide international power rather than raise the standard of living of their own population.

Why do the Chinese want to sell their stuff to the US, thereby accumulating dollars they save as US securities? The big reason is that the US is the world’s consumer, and if the Chinese want to grow their economy, they need demand to match supply. They have the supply, the US has the demand at present. As consumption increases in China and they develop a larger market for their own products, which is already happening, then they will be less driven to export in search of demand. At any point they wish they can switch any portion of their Tsy’s into reserves and from there into other financial assets or purchase real assets.

Actually, it’s not as simple as this, according to MIchael Pettis. The Chinese government has largely borrowed these funds from Chinese businesses that sold goods to the US. This money is owed in China, but China doesn’t want to repatriate it now for fear of increasing inflation.

China: What the PBoC Cannot Do With Its Reserves

“They have the supply, the US has the demand at present. ”

The Chinese have 1.3 Billion people that are also demanding goods. Moreover, they have an aging population in need of social services and medical care. They have roads that need to be built, as well as schools and hospitals and training centers. They have a shortage of just about everything, and an excess capacity to meet that shortage, except the capacity is being re-directed to supplying excess demand in the united states instead of at home. The leadership needs to be put on trial for this.

RSJ, Andy Xie, who is on the ground there, reports that the consumer market is developing rapidly now in China, and there will be increasingly less pressure to export as it grows. The Chinese aren’t “natural” consumers, the way Americans seem to be, not minding going into debt. Asians are traditionally savers, and they apparently need to learn how to shop. I expect that the women will lead the way. 🙂

That’s Good News, Tom. I have absolutely no problem with women shopping, be they Chinese or otherwise. The men can shop, too.

But there is still a problem, in that

1) The economy in China needs to adjust, to produce the things the Chinese need and are willing to pay for. Such a period of adjustment can be painful, with a lot of unemployment and liquidation. Government needs to seriously help here.

2) Relative prices in China have been distorted, as the Chinese cannot afford to buy the output of the firms they work for. As prices are sticky, this is another area where the Government needs to help.

3) There is still the question of a few decades of wasted resources, in which China oriented its economy to produce goods for the satisfaction of foreign wants instead of their own domestic wants, and imposed high taxes and forced savings programs on their own citizens, preventing the development of a healthy domestic market. I’d still go forward with the trials.

RSJ, as I understand Andy Xie and MIchael Pettis the Chinese went through a transition from a rural agricultural based economy, almost at the subsistence level of many people, to an urban industrial-based economy in a very short period. To do this they needed to export, since there was very little effective demand in the country for lack of income. There was probably plenty of notional demand, but it was mostly on the part of unqualified buyers. There was also potentially a lot of latent demand, in the sense that people would have bought stuff if they had something approaching a middle-class lifestyle.

The notional demand is not being converted to latent demand, as workers are being paid better wages and entering the middle-class. But this still have to be “converted” to middle-class shoppers. This is happening with the people who strike it rich, but more slowly for ordinary workers, who are accustomed to saving instead of spending and have not yet developed a desire to consume what we consider indispensable to life. But that is starting to happen, especially with younger people. But a lot of potential consumption is going into property for two reasons, one, Chinese people can now own property, and, two, the RE market is rising and people are rushing in so as not to get left out. This is producing inflation that the Chinese government is trying to control, so they don’t want to convert their dollars to yuan for domestic use. The dollars are either being saved or going to materials and capital investment.

China is still at the beginning stages of this and so they will likely be a big net exporter for some time. The good news is that contraction is the West has been taken up by domestic demand to a degree, so that the Chinese economy did not crash the way many had expected it would. But it’s not yet strong enough to counterbalance the West either, so it is unlikely that Chinese (and Indian) rapid growth will pull the global economy out of its problems.

We also have to remember that China has not yet faced its first big test. It did very well managing the contraction of exports and domestic slowdown by acting quickly with a big stimulus package. But most people feel that the real test will be managing the apparent housing bubble. If that blows up they are in trouble.

Correction: “The notional demand is not being converted to latent demand” should be “The notional demand is now being converted to latent demand.”

Tom Hickey: “The Chinese aren’t “natural” consumers, the way Americans seem to be, not minding going into debt. Asians are traditionally savers, and they apparently need to learn how to shop.”

Well, I don’t know if they aren’t good shoppers but they surely are “good” gamblers. The casinos in US are full of them and I know the reason for this is in their culture and traditions. For instance, during Chinese New Year they like to gamble so they can find out how lucky the entire year will be. They just have to start spending their money not only in the casinos :-).

Actually, gambling is illegal in the PRoC, so the Mainland Chinese one sees gambling are necessarily abroad. However, Chinese love to gamble and they often do it privately. Ma jiang (mah jhong) is like our Saturday night poker. Even though the Chinese are savers, they are not tight-fisted, and they don’t mind spending to enjoy themselves and social status has long been associated with material trappings. Mao tried to suppress this during the years of austerity. So there is a lot of latent demand there waiting to explode. They just need to get money flowing through the domestic economy.

The government has been emphasizing the supply side thus far, to the degree that many analysts see over-capacity. Their motto seems to be, “Build it and they’ll come.” It’s pretty clear that they intend to build a strong domestic economy, and their major problem is controlling the rate of growth so that things don’t get out of hand.

@rvm. There is another use of US financial assets that the Chinese can make us of. They can influence US political favor. China wants Taiwan. US financial assets may be the lever to get them Taiwan when the time is right.