I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

It will only take 6 months

I followed the attacks on pro-Israeli New York Times war monger Thomas Friedman some years ago, which centred on his support for the invasion of Iraq and his repeated prognosis that it would only take 6 months to decide the fate of the conflict. The six months never really materialised and by 2007 he was arguing, just as vehemently as he argued for war, for US disengagement because the strategy had failed. He was imbued with the WMD mania that was used by the US, Australian and UK governments to “justify” the unjustifiable despite them knowing there were no such dangers. So he is a guy who obviously knows what he is talking about! In his latest column he tries his hand at economics with a similar intellectual arrogance and lack of judgement that he brought to the Iraq issue.

As an aside, it was the Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting group that kept the issue of Tom Friedman’s Flexible Deadlines alive so that his lack of judgement was visible for all to see. If you followed the discussion your only conclusion is that Friedman was pushing a biased agenda behind the cover of this NTY column and was hopelessly inadequate at assessing the reality he was continually writing (berating) about.

As FAIR note:

Friedman’s appeal seems to rest on his ability to discuss complex issues in the simplest possible terms. On a recent episode of MSNBC’s Hardball (5/11/06), for example, Friedman boiled down the intricacies of the Iraq situation into a make-or-break deadline: “Well, I think that we’re going to find out, Chris, in the next year to six months – probably sooner – whether a decent outcome is possible there, and I think we’re going to have to just let this play out.”

That confident prediction would seem a lot more insightful, however, if Friedman hadn’t been making essentially the same forecast almost since the beginning of the Iraq War. A review of Friedman’s punditry reveals a long series of similar do-or-die dates that never seem to get any closer.

FAIR then listed 10 instances where Friedman proposed that the “next six months would decide everything” from 2003 to 2006, which leads them to conclude that is is a “long six months in Iraq”.

In his recent New York Times column – Root Canal Politics – (published May 9, 2010), Friedman takes a visit to the dentist. I think his commentary on the Middle East is appalling but his foray into economic analysis is worse.

He starts by issuing a Death Notice:

DEATH NOTICE: The Tooth Fairy died last night of complications related to obesity. Born Jan. 1, 1946, the Tooth Fairy is survived by 400 million children living largely in North America and Western Europe, known collectively as “The Baby Boomers.” “We’ll certainly miss the Tooth Fairy,” one of them said following her death, which coincided with the 2010 British elections and rioting in Greece. The Tooth Fairy had only one surviving sibling who will now look after her offspring alone: Mr. Bond Market of Wall Street and the City of London.

Sitting in America, it’s hard to grasp the importance of the British elections and the Greek riots. Nothing to do with us, right? Well, I’d pay attention to the drama playing out here. It may be coming to a theater near you.

That is, coming to a theatre near you in about six months!

His so-called “meta-story behind the British election, the Greek meltdown and our own Tea Party” is that the parents of the “Baby Boomers” were the “The Greatest Generation” and made “enormous sacrifices and investments to build us a world of abundance” whereas the Boomers are the “The Grasshopper Generation” having “eaten through all that abundance like hungry locusts”.

The solution is that we all have to become “The Regeneration” which “raises incomes anew but in a way that is financially and ecologically sustainable”.

As soon as I see the words “financial” and “ecological” together I get suspicious and when combined with the word “sustainable” I get really suspicious. And sure enough, I had reason to be when reading this account of the crisis and the way forward out of it.

Apparently, the Tooth Fairy is an analogy for the situation we have been living in which would “allow conservatives to cut taxes without cutting services and liberals to expand services without raising taxes”. Why did this happen? Well according to Friedman, who now is apparently an expert on macroeconomics:

The Tooth Fairy did it by printing money, by bogus accounting and by deluding us into thinking that by borrowing from China or Germany, or against our rising home values, or by creating exotic financial instruments to trade with each other, we were actually creating wealth.

Well there is a mixture for you. Some government transactions, some external sector transactions, and some non-government horizontal transactions, all in the same sentence.

I would also note that the Baby Boomer generation has only been adult in the post Bretton Woods period (after 1971) so the fiscal opportunities that our governments have had relative to the opportunities the Boomers’ parents had are vastly superior. Not that you would guess that from the way our governments have (largely) behaved over this time period.

But it gets more complicated than that. The period that the Boomers have been adults has also been characterised by the rise to policy dominance of the economic rationalists or neo-liberals. Accordingly, the way we now view the state has changed fundamentally. And this has meant that the policy terrain that we now labour under is far removed from that which our parents benefited from in earlier times.

They were first adults in the Post World War II period and had been more or less directly affected by the The Great Depression. That experience taught them that, without government intervention, capitalist economies are prone to lengthy periods of unemployment. The emphasis of macroeconomic policy in the period immediately following the Second World War was to promote full employment.

Inflation control was not considered a major issue even though it was one of the stated policy targets of most governments. In this period, the memories of the Great Depression still exerted an influence on the constituencies that elected the politicians. The experience of the Second World War showed governments that full employment could be maintained with appropriate use of budget deficits.

The employment growth following the Great Depression was in direct response to the spending needs that accompanied the onset of the War rather than the failed Neoclassical remedies that had been tried during the 1930s. The problem that had to be addressed by governments at War’s end was to find a way to translate the fully employed War economy with extensive civil controls and loss of liberty into a fully employed peacetime model.

So our parents enjoyed strong public sector infrastructure support and the benefits of the Welfare State. One of the things I get angry about is the fact that politicians who benefitted as kids and later while studying at university etc from the state support they received then in later life once they have influence try to undermine that welfare support structure for the next generation.

In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned we started in this way:

When we were young and later in our formative years, when we studied economics, everybody who wanted to earn an income was able to find employment. Maintaining full employment was an overriding goal of economic policy which governments of all political persuasions took seriously. Unemployment rates below two per cent were considered normal and when unemployment threatened to increase, government intervened by stimulating aggregate demand. Even conservative governments acted in this way, if only because they feared the electoral backlash that was associated with unemployment in excess of 2 per cent.

More fundamentally, employment is a basic human right and this principle was enshrined in the immediate Post World War II period by the United Nations. In 1945, the Charter of the United Nations was signed and ratified by 50 member nations. Article 55 defines full employment as a necessary condition for stability and well-being among people, while Article 56 requires that all members commit themselves to using their policy powers to ensure that full employment, among other socio-economic goals are achieved.

Employment transcends its income generating role to become a fundamental human need and right. This intent was reinforced by the United Nations in the unanimous adoption of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 23 of that treaty outlines, among other things, the essential link between full employment and the maintenance of human rights …

While unemployment was seen as a waste of resources and a loss of national income which together restrained the growth of living standards, it was also constructed in terms of social and philosophical objectives pertaining to dignity, well-being and the quest for sophistication. It was also clearly understood that the maintenance of full employment was the collective responsibility of society, expressed through the macroeconomic policy settings. Governments had to ensure that there were jobs available that were accessible to the most disadvantaged workers in the economy. We call this collective enterprise the Full Employment framework.

That framework has been systematically abandoned in most OECD countries over the last 30 years. The overriding priority of macroeconomic policy has shifted towards keeping inflation low and suppressing the stabilisation functions of fiscal policy.

Concerted political campaigns by neo-liberal governments aided and abetted by a capitalist class intent on regaining total control of workplaces, have hectored communities into accepting that mass unemployment and rising underemployment is no longer the responsibility of government.

As a consequence, the insights gained from the writings of Keynes, Marx and Kalecki into how deficient demand in macroeconomic systems constrains employment opportunities and forces some individuals into involuntary unemployment have been discarded.

The concept of systemic failure has been replaced by sheeting the responsibility for economic outcomes onto the individual. Accordingly, anyone who is unemployed has chosen to be in that state either because they didn’t invest in appropriate skills; haven’t searched for available opportunities with sufficient effort or rigour; or have become either “work shy” or too selective in the jobs they would accept.

Governments are seen to have bolstered this individual lethargy through providing excessively generous income support payments and restrictive hiring and firing regulations. The prevailing view held by economists and policy makers is that individuals should be willing to adapt to changing circumstances and individuals should not be prevented in doing so by outdated regulations and institutions.

The role of government is then prescribed as one of ensuring individuals reach states where they are employable. This involves reducing the ease of access to income support payments via pernicious work tests and compliance programs; reducing or eliminating other “barriers” to employment (for example, unfair dismissal regulations); and forcing unemployed individuals into a relentless succession of training programs designed to address deficiencies in skills and character.

In the midst of the on-going debates about labour market deregulation, scrapping minimum wages, and the necessity of reforms to the taxation and welfare systems, and cutting back on fiscal deficits, the most salient, empirically robust fact of the last three decades – that actual GDP growth has rarely reached the rate required to maintain, let alone achieve, full employment – has been ignored.

Further, the current crisis, which is getting worse again in Europe, has demonstrated beyond doubt that this paradigm is bereft of credibility. The ideologically-asserted belief that “free markets” were the best organising framework for the advancement of societal welfare and income generation and that they would “self regulate” to deliver these optimal outcomes – which is really the stuff of the Tooth Fairy Land – has been crushed by the events of the last 3 years.

None of this came as a surprise to those of us who operate within the framework presented by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). It was obvious from the start that the move towards deregulation of all markets and the contraction of the government sector which was associated with rising non-government (particularly household) indebtedness was not a viable long-term growth strategy.

Once the private sector sought to save again overall and reduce its debt exposure then the fiscal drag coming from ideologically suppressed fiscal positions (often budget surpluses) would deliver a major recession. The collapse of the financial sector was always imminent given the reduced (and lax) regulation that the lobbyists had pressured governments around the world into introducing.

So Friedman is traversing a very complex historical period. He wrongly seeks to compare the welfare augmenting acts of government (during the full employment period) with the destructive deregulation acts of government (during the neo-liberal period). These periods are not commensurate.

Further, I am not sure who he thinks is borrowing from China.

But I agree with him that the neo-liberal period which has dominated the period that the Boomers have been maturing has created the illusion that nominal wealth is real wealth or ponzi wealth is real wealth. For those who have lost significant nominal wealth in the crisis the distinction will surely be obvious.

But this is not to say that there has not been a major accumulation of real wealth over this time. There has been but not everyone has shared in it.

In this blog – The origins of the economic crisis – I argued that the roots of the crisis were in part to be found in the way in which the neo-liberal policy agenda (the attacks on unions etc) allowed a major divergence between productivity growth and real wages growth to occur from around the mid-1980s (the date depends which country you are talking about).

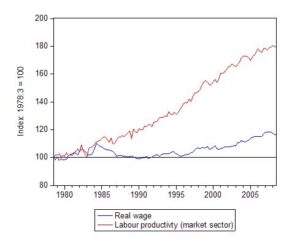

This graph applies to Australia but the trend is apparent in most countries. You can see that real wages have failed to track GDP per hour worked (in the market sector) – that is, labour productivity. Real wages fell during the 1980s under the Hawke Accord, which was a stunt to redistribute national income back to profits in the vein hope that the private sector would increase investment. It was based on flawed logic at the time and by its centralised nature only reinforced the bargaining position of firms by effectively undermining the traditional trade union movement skills – those practised by shop stewards at the coalface.

Under the Howard years (1996-2007), some modest growth in real wages occurred overall but nothing like that which would have justified by the growth in productivity. In March 1996, the real wage index was 101.5 while the labour productivity index was 139.0 (Index = 100 at Sept-1978). By September 2008, the real wage index had climbed to 116.7 (that is, around 15 per cent growth in just over 12 years) but the labour productivity index was 179.1.

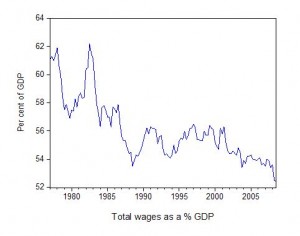

What happened to the gap between labour productivity and real wages? The gap represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital. The Federal government (aided and abetted by the state governments) helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation; the National Competition Policy to name just a few of the ways. The next graph depicts the summary of this gap – the wage share – and shows how far it has fallen over the last two decades.

Of-course, such redistributions created tensions for the capitalist system. If the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself? This is especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector since around 1997 (in Australia)

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumptions goods produced were sold. But in the recent period, capital has found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals that we have read about constantly over the last decade or so.

The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages.

The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing federal surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold.

And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This is the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

So there were real gains to be made with all this deregulation and it is obvious that very few bankers have lost very much of their “wealth” during the crisis.

As noted in this blog – Fiscal sustainability and ratio fever – the The Sunday Times Rich List reported (April 25, 2010) that “the collective wealth of the 1,000 multimillionaires … [was up by] … 29.9% … easily the biggest annual rise in the 22 years of the Rich List”.

So despite the most significant economic downturn in 80 years and sharply rising unemployment and home foreclosures, the top-end-of-town overall enjoys dramatic improvements in thier fortunes.

This directly bears on Friedman’s “Grasshopper Generation” stylisation. There are now massive inequalities which have been exacerbated by the crisis but which were widening as the neo-liberal onslaught gathered pace. Some of the Boomers have clearly been eating well indeed, while others have been enduring increasing relative poverty.

As noted above, the Boomer period saw persistently high rates of labour market underutilisation which clearly imposed disproportionate burdens on certain segments of society and allowed the conservatives to reengineer the distribution of income in favour of the wealthy.

And that was Marx’s point that I discussed in this blog – Fiscal sustainability and ratio fever – that at the height of the crisis – when there is so much (over)-production – the ones who created the real goods and services (the workers) have less than ever.

Friedman then continues to catalogue the problem but gets hopelessly confused:

Greece, for instance, became the General Motors of countries. Like G.M.’s management, Greek politicians used the easy money and subsidies that came with European Union membership not to make themselves more competitive in a flat world, but more corrupt, less willing to collect taxes and uncompetitive. Under Greek law, anyone in certain “hazardous” jobs could retire with full pension at 50 for women and 55 for men – including hairdressers who use a lot of chemical dyes and shampoos. In Britain, everyone over 60 gets an annual allowance to pay heating bills and can ride any local bus for free. That’s really sweet – if you can afford it. But Britain, where 25 percent of the government’s budget is now borrowed, can’t anymore.

You can see how out of his depth on these issues he is. I am sure he has been reading Peter Schiff or some other economic illiterate when he was writing all this.

So the attack is not really on private indebtedness which was not clear in the article until this point. He is squarely aiming at public net spending and the associated debt-issuance. Note that this associated debt-issuance is a neo-liberal construct and imposed, unnecessarily, on governments to maintain their perverted notion of fiscal discipline. Clearly, from their own assestment (twisted logic) it has failed to do that but that is not the point I want to make.

What happens if the government wasn’t issuing any public debt? A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. In that sense, it doesn’t issue debt to “fund” itself. So do a mental experiment and assume that governments become enlightened and stop issuing debt.

Further, worries about their being enough tax revenue are also meaningless from the perspective of “funding” government spending. As I explain in this blog – Taxpayers do not fund anything.

With those insights from MMT, then re-read Frieman’s last quote. The question shifts from a faux notion of financial affordability to whether there is enough real goods and services available to accommodate the needs of the demographic cohorts being “supported”.

It is quite irrelevant how much of the British government budget is borrowed. If there are heating materials available and enough steel to make the buses that drive down the road, then the British government will always be able to afford to purchase them. The question is whether it is politically possible to provide for these specific items against other competing needs. The analysis always has to focus on what real resources are available. Friedman has no inkling of that issue.

It gets worse, as Friedman gets all intergenerational with us:

Britain and Greece are today’s poster children for the wrenching new post-Tooth Fairy politics, where baby boomers will have to accept deep cuts to their benefits and pensions today so their kids can have jobs and not be saddled with debts tomorrow. Otherwise, we’re headed for intergenerational conflict throughout the West.

This so-called trade-off has no foundation. There is no such trade-off in financial terms. The conflict will come if idiots like Friedman keeps perpetuating these myths. They are akin to the WMD myths that he broadcasted far and wide to give the corrupt US government the smokescreen they required to get a footing in the Middle East.

The only issue is whether the consumption desires of the pensioners (the boomers) and their kids are commensurate with the supply of real goods and services as time passes.

There is clearly one area where there is conflict in this sense. In Australia, housing affordability is so low now that the boomers’ kids are finding it hard to access the real estate market. There will be a fundamental change over the next 20 years or so in attitudes towards home ownership in this country. The kids will become the renters and their parents the landlords. But then Europeans, for example, came up against this finite land issue some hundreds of years ago.

Another area of conflict is in the environmental degradation we are leaving future generations.

But the real scarcity of land has no relevance to the public debt ratio. The government’s debt level never (in financial terms) alters its capacity to spend. A sovereign government has the same financial capacity to buy goods and services or pay pensions whether it is carrying zero debt or “high” levels of debt relative to GDP. Note the parenthesis around “high” – which signifies that such descriptors are without much meaning. What is high? What is low? The answers are irrelevant to a sovereign government in financial terms.

The only meaning is in political terms and every generation more or less, chooses its own tax burden as a matter of political choice. The current dominant adult generation cannot impose a higher tax regime on a generation 100 years from now. They will choose when the time is up based on the needs to control aggregate demand and provide the government sector with idle real resources to pursue its socio-economic program.

Friedman, sadly, then decided that he would get onto the “need” for austerity – at the height of a crisis no less.

He waxes lyrically about a “British Conservative candidate” in the recent election who told him that:

… the Tories’ most effective campaign ad was a poster showing a newborn baby under the headline: “Dad’s eyes, Mum’s nose, Gordon Brown’s debt.” Beneath was the caption: “Labour’s debt crisis: Every child in Britain is born owing £17,000. They deserve better.”

They certainly deserve better. They deserve to grow up in a nation that is free from cretinous-level political debates and false advertising. No child born in Britain legally owes anything upon birth. Their parents might have debts but they will be the result of private contracts they have signed with creditors. The public debt held by the British government is a liability only of itself.

Friedman focuses more deeply on the austerity issue:

Here is how The Financial Times described it on April 26: “The next government will have to cut public sector pay, freeze benefits, slash jobs, abolish a range of welfare entitlements and take the ax to programs such as school building and road maintenance.” Too bad no party won a majority mandate in the British elections to do this job.

After 65 years in which politics in the West was, mostly, about giving things away to voters, it’s now going to be, mostly, about taking things away. Goodbye Tooth Fairy politics, hello Root Canal politics.

The last thing any British government should be contemplating right now is cutting net spending. Private spending in Britain is dismal and the slight net export improvements are being driven by the depreciating sterling and falling import spending (as a result of the parlous state of the economy). As I demonstrated in this blog – People are now dying as the deficit terrorists ramp up their attacks – the only thing that Britain has going for it at present is its public deficit.

Start cutting that and you will see rising deficits as the economy collapses again and the automatic stabilisers go to work to provide some floor in aggregate demand.

Now is the time to expand public sector employment and pay, expand pensions and welfare entitlements and to increase investment in school buildings and road maintenance. Well perhaps invest in aged care facilities that are humane and public transport systems rather than school buildings and road maintenance. But spend nonetheless.

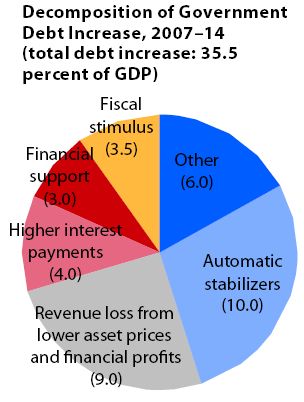

I might also remind Friedman that he should acquaint himself with the facts. In the April 2010 IMF World Economic Outlook, the following interesting pie-chart appeared. Accompanying the chart is relevant text.

On Pages 5-6 of the April WEO you read:

Fiscal policy provided major support in response to the deep downturn, especially in advanced economies. At the same time, the slump in activity and, to a much lesser extent, stimulus measures pushed fiscal deficits in advanced economies up to about 9 percent of GDP.

Read it twice! Then E-mail it to Friedman!

On Page 9 of the April WEO you read:

Fiscal balances have deteriorated, mainly because of falling revenue resulting from decreased real and financial activity. Fiscal stimulus has played a major role in stabilizing output but has contributed little to increases in public debt, which are especially large in advanced economies.

Read it twice! Then E-mail it to Friedman!

The way to get the public deficits down and start stabilising public debt ratios (as if these goals meant anything) is to stimulate economic growth. That will not occur via austerity programs. That will only worsen living standards and push the ratios further into the realm of conservative hysteria.

The automatic stabilisers are reversable. That is why they are called automatic. There is no political dilemma involved – no programs that have to be cut – no incomes that have to be savaged. The budget balance is largely endogenous and is driven by private spending growth. Once that improves, which it will as public spending multiplies through the income generation process, then the budget balance will fall both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP.

The way to cut deficits is through growth. You cut a deficit by expanding it.

And finally today, Friedman is worshipping at the alter of the bond traders without the slightest lateral thought coming into his head:

We have got to use every dollar wisely now. Because we’ve eaten through our reserves, because the lords of discipline, the Electronic Herd of bond traders, are back with a vengeance – and because that Tooth Fairy, she be dead.

There are some very real ways in which we have “eaten our reserves”. Our natural environment has been compromised – perhaps beyond repair; our climate is changing – perhaps irretrievably; conventional energy resources are dwindling; and our landscape is denuded through poor farming practices. Behaviour in this regard has to change for our kids to have a future.

But that is not what Friedman is referring to.

Finally, if the bond traders reduce the capacity of sovereign governments to pursue public purpose then there is one easy solution. Cut them out of the action. This can be done obviously by finally scrapping the neo-liberal practise of issuing debt to match net spending. It could also be accomplished by the central bank controlling the yield curve at appropriate maturities. The first option is optimal; while the second is a cop-out.

But ultimately it is always a sovereign government that rules. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

As an aside, while I read the NYT regularly, this article was also brought to my attention by a regular reader from Southern California. He lives near to Beacon’s Beach (down Encinitis way). If you know it (that is, you can find the beach at the end of the street) the left-hander off the south reef there is a pretty neat wave. Also, viewing the sunset from the cliff top is an experience that is worthwhile having at least once in your life. Nice place.

Coming up!

Many readers have written in asking me to explain what the US Federal Reserve swap lines, which have just re-opened, are all about. Some note my not-so-subtle reference when talking about the appalling behaviour of the European Central Bank to the bailouts they received courtesy of the US government.

Well tomorrow or another day soon I will explain what this is about and why it is exposing the US Federal Reserve to enormous default risk.

Also tomorrow the Australian federal government brings down its annual budget and I have columns to write for newspapers on that. So there might be some overlap with the blog depending on what other things I have to do in my writing time tomorrow.

But then I might write about something completely different tomorrow. Each day always brings a new slate!

That is enough for today!

Nice post,

Can you also comment on the “quantative easing” that the ECB will start soon:

http://www.businessinsider.com/ecb-will-begin-quantitative-easing-2010-5

you say “What happens if the government wasn’t issuing any public debt? A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. In that sense, it doesn’t issue debt to “fund” itself. So do a mental experiment and assume that governments become enlightened and stop issuing debt.”

I will try but the possibilities seem endless! I can’t see goverments will never admit that their currency has no intrinsic value and if the great unwashed can’t relate then they would loose authority or power somehow…

Very interesting post. It is clear that stagnating wages and inequality have something to do with. In fact, this is a point made not only by ‘progressive’ economists but also by, for example, R. Rajan at the Univerisy of Chicago. More traditionally left-wing, David Harvey makes a similar (if not the same) point in his latest book: his lecture at the LSE the other day (available at the LSE website) summarises this view very well.

What is unclear to me however is the following two points:

– there are distributional effects here. Financial engineering did not impact on every sector in the same way. In fact, it can be argues that household indebtedness contributed to the housing industry primarily. Elisabeth Warren’s argument that main differences between the 1970’s and now is in the percentage of income going towards housing, health and school fees but not other items is instructive. Harvey makes the point that urban policy is at the centre here. So, we cannot quite argue that the suppression of labor worked uniformly.

– To charge governments and loose ‘capitalists’ with manufacturing this through policy choice is to ignore that wages stagnating also due to secular trends e.g. competition from unskilled labour in the third world, immigration and so forth. In other words, this is more of an emergent phenomenon than some sort of pre-meditated policy choice.

The Real Wage vs. Productivity graph is the same for the U.S. We must reestablish the link between wages and productivity if other segments of society are to experience the benefits of an economic recovery. This means breaking up the “neoliberal policy box” that workers have been placed in.

“I followed the attacks on pro-Israeli New York Times war monger Thomas Friedman…”

Out of curiosity, what does Israel have to do with anything?

Ilya –

The pre-meditated policy choice was to keep inflation low. Everything that followed was a means to an end – including policies that supported wage suppression. Financial engineering (via increased household leverage) and IMO, cheap imports, were a way to ameliorate the effects of stagnate wages.

What I wish someone with a microphone was willing to ask these \”experts\” who are advocating these austerity packages is this:

You are advocating these packages because you fear that our rising deficits will lead to higher interest rates and higher costs of funding new growth potential business opportunities, which will lead to slower growth and lower wages and higher taxes for all (an escalation in our budget deficit). Why do you think the answer for potentially lower wages and lower growth is FORCED lower wages and lower growth??

“Many readers have written in asking me to explain what the US Federal Reserve swap lines, which have just re-opened, are all about. Some note my not-so-subtle reference when talking about the appalling behaviour of the European Central Bank to the bailouts they received courtesy of the US government.”

Please do! My gut is telling me that the fed is creating dollar losses somewhere to weaken the currency.

What does MMT have to say about wealth/income inequality, the time changes between spending and earning that debt allows, and changes in retirement dates?

“What happened to the gap between labour productivity and real wages? The gap represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital. The Federal government (aided and abetted by the state governments) helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation; the National Competition Policy to name just a few of the ways. The next graph depicts the summary of this gap – the wage share – and shows how far it has fallen over the last two decades.”

In the USA, you can add legal immigration and illegal immigration.

“Very interesting post. It is clear that stagnating wages and inequality have something to do with. ”

You need a price inflation target too.

Does savings of the rich equal dissavings of the gov’t plus dissavings of the lower and middle class?

“What happened to the gap between labour productivity and real wages? The gap represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital.”

That is probably the same all around the industrialized world. And probably the biggest loss for labor is not the monetary redistribution in itself but the loss of dynamic effects in real growth that would have been with full employment and more money in the hands of the many.

Bill is being a bit insulting in suggesting that politicians and others are targeting inflation control with a total indifference to unemployment. No one with an ounce of humanity is indifferent to other people’s unemployment.

The problem is inflation. I agree with Bill that much of the stuff we get from deficit terrorists and scaremongers is rubbish, on the other hand the latest inflation figures in the U.K. is about 3.5%. What’s the UK government supposed to do? Bump up demand and let inflation rise to 5%….7%? Granted this 3.5% looks like a temporary spike, but the U.K. government – central bank machine is right to go carefully just at the moment.

I suggest the deterioration in the inflation unemployment relationship between the end of WWII and around 2000 was due to the fact that just after WWII people had memories of the 1930s and were grateful for a job. Plus they needed the money for what are now considered essentials. In contrast by around 1970 people and trade unions had become blasé and arrogant. One of the bolshyest union leaders in the 1970s U.K. (Hugh Scanlon) admitted in his retirement that unions had by the 1970s become too powerful.

Ralph Musgrave said: “Bill is being a bit insulting in suggesting that politicians and others are targeting inflation control with a total indifference to unemployment. No one with an ounce of humanity is indifferent to other people’s unemployment.”

The spoiled and the rich along with the bankers don’t care at all. They are only worried about using an oversupplied labor market to achieve negative real earnings growth on the lower and middle class and more debt for them (access to credit). This allows the spoiled and rich to “steal” the real earnings growth and retirement of the lower and middle class.

“The problem is inflation.”

The problem is debt inflation that leads to asset price inflation and some price inflation without enough or any wage inflation.

“I agree with Bill that much of the stuff we get from deficit terrorists and scaremongers is rubbish, on the other hand the latest inflation figures in the U.K. is about 3.5%. What’s the UK government supposed to do? Bump up demand and let inflation rise to 5%….7%? Granted this 3.5% looks like a temporary spike, but the U.K. government – central bank machine is right to go carefully just at the moment.”

Raise interest rates to get the debt out of assets and prices. In the future price inflate with currency and a balanced economy instead of price inflating with debt and an unbalanced economy (too much going to capital).

Dear Phil

I wasn’t taking a position on Israel. The point I was making is that Friedman has often made rather disparaging remarks about Arabs in his narratives about the Middle East and this bias permeates his judgements on events such that only one perspective is ever presented. His readers are thus mislead about what are otherwise very complex and sometimes unfathomable situations.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Thanks for clarifying. Personally, I don’t have an opinion on Israel the country one way or another. Your brief mention of Israel, however, is one of many that I’ve noticed recently. It made me wonder if there was some event that I was not aware of.

–Phil

Nice post, Bill. I think that Mr Friedman must do his research at New York and Washington cocktail parties. He is just another shill parroting the current line and amplifying the message in the media echo chamber.

Nothing really to add to this excellent post, other than to say how pleased I am that you took on that pompous, ignorant a-hole, Tom Friedman. This is what counts as an “intelligent”, “influential” journalist in the US. The Australian surf beckons!

“Bill is being a bit insulting in suggesting that politicians and others are targeting inflation control with a total indifference to unemployment. No one with an ounce of humanity is indifferent to other people’s unemployment.”

“Rising unemployment was a very desirable way of reducing the strength of the working classes . . . What was engineered – in Marxist terms was a crisis in capitalism which recreated a reserve army of labor, and has allowed the capitalists to make high profits ever since.”

Alan Budd – chief economic advisor to Margaret Thatcher

Usually when inflation is argued in defense of monetary and treasury policies that don’t promote full employment in Sweden it usually does refer to the model world never with empirical facts. The fact is that since the 70s one can easily see that prices rise before wages. And here when the inflation did go beyond international imported inflation it is when there have been tax hikes on consumption and/or evaluation of the currency, most of them of the competitive sort not that there was any serious long run problem with trade balance. But during the more economically democratic post war decades there was wage driven inflation. But it’s quite a difference when there is a brad prosperity rise for all in society caused by full employment compared to the inflation that occurred in the following decades.

Excellent takedown of Friedman.

The guy is an anti-arab bigot, and his analytical powers are not much better than that of an English-Terrier. He can sniff out the threat of Arabs anywhere, but not do much more than that. Anytime you see his tail pointing and ears pricked, you know he has discovered someone brown and dangerous.

He is completely trapped in a paradigm in which Silicon Valley Enlightened Cosmopolitan Eco-Entrepreneurs are battling against dim-witted dark age traditionalists. Somehow the traditionalists always tend be on the east side of the Green Line. It would be laughable if he didn’t have the platform.

And recently he has turned into our own war mongering Father Coughlin, who also ostensibly advocated for social justice, but only for the right people — while the wrong people needed to be “taught a lesson” and beaten into submission.

Ralph,

Nobody in government has an ounce of humanity and that is why they constantly look after the top by using unemployment as a buffer against inflation.

When the GFC hit the first group put into lifeboats were the top end of town. The average person was left to drown.

Cheers.

Greg: “What I wish someone with a microphone was willing to ask these \”experts\” who are advocating these austerity packages is this:

“You are advocating these packages because you fear that our rising deficits will lead to higher interest rates and higher costs of funding new growth potential business opportunities, which will lead to slower growth and lower wages and higher taxes for all (an escalation in our budget deficit). Why do you think the answer for potentially lower wages and lower growth is FORCED lower wages and lower growth??”

Because lower growth is OK if it produces lower wages. (It is so hard to find good help these days.)

Ralph Musgrave: “Bill is being a bit insulting in suggesting that politicians and others are targeting inflation control with a total indifference to unemployment. No one with an ounce of humanity is indifferent to other people’s unemployment.”

You know, Ralph, I would have agreed with you a few years ago. Then Katrina hit. Planned incompetence aside, it was a national Rorschach test. Conservatives, regular people like my friends and relatives, did what they could to help. But conservative pundits and politicians revealed a degree of indifference and lack of humanity that surprised me. I have a friend who has long held that they are just mean people, and now I agree with her. As for unemployment, their ideology tells them that for the most part the fault lies with the unemployed. As a result, habitual indifference to unemployment and ideological fear of socialism has resulted, not only in a lack of action, but in a dogged obstruction of measures to bring down unemployment, even for those who admit that the unemployed are not at fault this time around. Ideology robs people of their humanity.

There will be a fundamental change over the next 20 years or so in attitudes towards home ownership in this country. The kids will become the renters and their parents the landlords. But then Europeans, for example, came up against this finite land issue some hundreds of years ago

……………

finite land issues ? The issues of unaffordability for the children of their boomer landlords has less to do with a land shortage [even though there is considerable density in some urban centres] and more to do with restrictive planning regulations.

it sounds like you want to accept a rentier class generation because it chimes with some myths you may have re finite housing resources that aren’t predominantly politically created.

the political class want to maintain the value of housing for [boomers predominantly], in the real world there is no shortage of materials with which to build housing nor a shortage of labour with which to construct those houses, but increasing supply could potentially remove one of the legs that currently keep the existing stock of housing excessively high. it would also not suit the situation for banks who’d presumably suffer from loan losses, because of the excessive amounts lent to fund high prices during the boom.

/L said: “The fact is that since the 70s one can easily see that prices rise before wages.”

Does the amount of debt go up before prices? Is the order debt goes up, asset prices go up, price inflation goes up, then wages go up?

Oh, I heard someone mention the housing shortage! Erm, 1 in 15 Melbourne homes are vacant.

http://www.earthsharing.org.au/2009/11/25/i-want-to-live-here-report-2009/

So, before we open up the thousands of hectares on the fringes of cities, probably occupied by land speculators (and let leash the excess of urban sprawl), how about we *tax land* in order to make 1) land more affordable (so anyone who wants to access the market can access it), 2) force speculators to relinquish the land to the people who want to live on it, not just hoard it for speculative gain, 3) stop raping capital and labour. Alas, the political classes prefer landlords first, capitalists second and labour third.

Plus, rasy restrictions and increasing the supply does not put downward pressure on house prices – overinflated land values have been compatible in all geographical areas – those with large areas and those without – look at the U.S and the Panic of 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893 etc; the Melbourne Land Boom of the 1890s; the 1974 property bust- what determines house prices is ultimately 1) land monopoly (and institutional investors, who might withdraw land from supply) and (2) credit. If you open up supply, all you get is speculators hoarding the land, or charging tomorrow’s output today (i.e. our mortgages).

Indeed, I find it ironic that back in the 14th century (in the UK) real wages were the highest (and 80% of the state was funded through rents), while today – in a “progressive” age – they are lower. The distribution, as I’m sure Bill knows, is not just wages being sacrificed at the gain of profits, but also rents – most people’s wages go toward paying rents, the mortgage etc while most profits are really ‘rents’ – construction giants and banks thrive on inflated land prices.

Henry George was right.

Spadj,

>Henry George was right.<

He most certainly was. That is an amazing bit of research.

@spadj

it has to be more complicated than developer land banks and credit availability that determines house prices.

in the uk for instance mortgage borrowing for house prices is well down on it’s levels during the peak….as banks still have tighter lending criteria, but that hasn’t prevented double digit annual house price inflation. the fiscal stimulus, which reduced unemployment expectations and successive interest rate drops have arguably lead to the recovery in prices.

confidence in addition to more affordable borrowing costs seem to have made a big difference.

Tricky,

What you listed can be included in the two factors I outlined. For example, I noted credit availability would clearly fall into “as banks still have tighter lending criteria” while land monopoly clearly responds to other factors – infrastructure spending, population growth etc – these expectations help investors going in on the action. In fact, George listed several things: speculation (and expectations), credit as well as common labour over a finite resource (i.e. “fiscal stimulus”). So in no way is “confidence in addition to more affordable borrowing costs seem to have made a big difference” incompatible with what I listed.

Thank you for allowing me to clarify that.

Also I think MMT and Georgism can work together – I often hear counterarguments against the single tax that it cannot “fund government” (although George thought other taxes could be added on other natural resources or even things like tobacco) . I remind people tax payers do not fund government; government funds taxpayers. I also believe land tax – is a nice way to control inflation and “soak up” excess cash via a rising rental value (although again the deadweight losses from all these other taxes would liberate our productive capacity).

Land tax also keeps government to the direct purpose: socialisation of investment. As a general rule, aggregate rents, roughly, equal aggregate government expenditure: look up Stiglitz who created the “Henry George Theorem”. It is a more equitable tax, as well as being efficient (let’s face it, taxing corporations doesn’t get utopia – most tax breaks are in real estate – and mosof the affluent are income poor, asset rich).

And, of course, I think a land tax would stop the business cycle – at leas the Kuznets wave, which I believe can be linked with booms and busts in property.

Fed Up: Re indifference to other peoples’ unemployment, obviously employers are indifferent – you are right – I overstated my case there. However, the more fundamental point here is Bill’s claim that policy makers (i.e. politicians) have targeted inflation and virtually ignored employment.

My basic point is that these politicians are not indifferent to the unemployment of others: it is not even in the interests of right wing politicians to be indifferent, since unemployment loses votes.

Re asset price inflation, I agree there has been far too much in the last two or three years. This has stemmed from stimulus money being stuffed down the throats of Wall Street with Main Street (i.e. wages) getting too little.

/L: I’d like to know where Alan Budd’s evidence is for dramatically rising profits. I’ve got a chart of profits as a proportion of GDP in the UK. Not sure where I got it, but I put it on my blog for you to look at (http://ralphanomics.blogspot.com/ ). Sorry it’s blurred. It runs from 1955 to 2009. Looks to me like profits averaged about 20% of GDP in the first half of that period and about 22% in the second half: not a dramatic rise.

And Willem Buiter (former member of the Bank of England monetary policy committee) claims that this percentage has remained stable “since Hannibal crossed the Alps”. Now I really would like to see the evidence for that. ( see http://www.nber.org/~wbuiter/newec.pdf)

Ralph Musgrave says:

I don’t know Budd’s evidence for his statement, my point was that according to him policies was deliberately made to create unemployment tom shift more power in society from labor to capitalists. Your graph looks like the trend for profit was downwards until 1976 and then the trend shifted to an upward direction.

Any F. A. Walker supporters in the house ?

Fed Up says:

Sorry I don’t know that. The price hikes was usually pushed by devaluation and/or tax hikes. The prevalent misguided ideas among politicians then were to boost investment in industry/export to recreate the 50s and 60s where industrial employment share was as greatest. They were of the idea that despite that there wasn’t full utilization of capacity that curbing consumption should boast industrial investment above normal. It didn’t work, real wages did drop and profits boomed and we got a speculation economy that finale in the early 90s crash. After the deregulation of currency and capital but with a pegged currency the debt leverage did grow immensely. Before that I don’t know the state of debt. In the beginning of the 90s crisis private sectors debt was immense and real estate values were high, a “thrifty” public sector did have a “strong” balance sheet, no financial deficit. Then real estate values dropped on average 30%. All in all after the crisis about one trillion debt in crowns was lifted of private sector and moved to the public sector balance sheet.

One has to remember that in Sweden the export sector is immensely powerful, historically it have been controlled almost by only one family. Everything about economy is about export sector, from mid 70s to early 2000 the domestic market, consumption, have grown poorly, at the bottom in OECD.

Hi-

“The only meaning is in political terms and every generation more or less, chooses its own tax burden as a matter of political choice.”

In the case of debt and debt repayment, it seems like “less” is the operative term. The parents leave a redistribution scheme in place whereby they spent real money on their needs in return for promises to the richest citizens for repayment at future time, redistributed from future revenue. One could term this a savings and investment scheme if one is in a charitable mood. But they generally leave the richest citizens to continue gathering wealth by virtue of having wealth, leading to the same dynamic occuring over and over in perpetuity.

Taken to high levels, this debt can saddle future generations with repayment schedules that cut severely into their freedom to chose their own tax burden and spending priorities. So much so that those future generations might very well have an incentive to default on these domestic obligations rather than put up with this redistribution perpetually, or with the kind of inflation/debasement that would be another escape.

You paint the resolution of debt as a magical function of economic growth. But the future period may not be one of much growth, between demographic decline and resource limitation. Besides, the capacity of the sovereign government to engage in debt is unlimited, as you often note, so it is not necessarily linked to economic performance, whether high or low, anyhow.

“Taken to high levels, this debt can saddle future generations with repayment schedules that cut severely into their freedom to chose their own tax burden and spending priorities.”

Huh? They choose this with complete freedom. There is no distributional problem that a 90% upper income tax bracket can’t solve. The problem is that the middle has been duped into thinking it is just around the corner from being in that upper bracket. There is no transfer of resources, whether real or financial, that can be imposed from one generation to another

But then, in essence, if our present promises are as worthless as you imply, then one shouldn’t wonder when there can be credibility issues with regard to domestic debt. Which leads to the conclusion that there are default or default-like risks there as well. And that these are related to the amount of debt being piled up.

Here in Sweden it have now been accepted by everyone that public surplus is something to have and strive for, so called public saving. Especially that it is saved in public pension funds that is one of the biggest players on our financial markets. The household analogy is used, save for a rainy day. But as I understand it the day it going to be used it’s is in no way any different from using the central banks printing press, the same considerations how it impact the utilization of the real economy and available resources have to be made.

The only real way to “save” for feature generations and pensioners is to handover an economy that is as efficient and productive as possible and takes the best use of available resources. As one of our now gone economists fruitless for a decade or more tried to make the point on, we can’t save health care, hair cuts or butter and the later will definitely turn rancid. The only thing we can do is make sure there is as much as possible productive capacity to produce health care and butter available for the pensioners then. And it really doesn’t matter what the financial construction of the pension system is, pay as you go or savings, in a national perspective. And to “save” now by having unemployment and a smaller economy than possible is the biggest swindle of pensioners and future generations; they will inherit a less productive society.

The EU bosses is now conducting an great defraud on future generations when they want to deliberately create unemployment and a smaller economy than possible.

If you can’t save in your own currency one could think that it works the same way the opposite way, you can’t really go in debt in your own currency. You can have commitments to hand over a sum of money in the future but it always in total has to be considered how it impacts the utilization of available resources.

“But then, in essence, if our present promises are as worthless as you imply, ”

Are you suggesting that a government that increases taxes is defaulting on it’s debt? When you buy debt, are you buying a return, or a promise that your children will never need to work in the future?

A government is not promising you the latter, but the former. The government’s promise is credible, but anyone who promises you or your heirs an entitlement to a certain lifestyle is not credible. If those promises emanate from your own mind, then they are even less credible.

No, I was not making that equation. I think your assumption that taxes can be raised indefinitely to cover rising debt levels is unrealistic, Firstly, it is more likely that inflation would be used to resolve it. Second, at some point of profligacy, restructuring would be considered, as a political distribution issue, if debasement of the currency is not desirable. Those are the choices- default, high taxation to recover a requisite portion of future GDP to cover debt payments, or inflation to reduce its value indirectly.

None are palatable, thus some discipline seems advisable when getting into high debt situations. As Japan shows, high debt *can* be completely palatable. But if high amounts of the debt were to be redeemed there, causing inflation, then causing interest rates to rise and the need for higher interest rates than inflation… they might be caught in a serious trap, where rolling over prior debt becomes very expensive. They are nowhere near that today, but it is a worry.

We also have to keep in mind the ~28 trillion on private debt that is far more economically unstable than the federal debt is. All the same, there are risks to federal debt as well, in the long run. If it is used as a stabilization device as Bill mostly argues for, then all well and good. But in the good times, there has to be a way to have it come down. This means that export/import balances also have to even out over the very long term for a sovereign government, I guess.

Burk, I wasn’t advocating raising taxes at all — in terms of total tax burden. As government interest costs are less than the growth rate of tax revenues, the latter does not need to be increased. Any Debt/GDP ratio can be stabilized simply by doing nothing — provided that you are a sovereign government and so have no default risk.

But you were pointing out a general principle that one generation can allow income to be concentrated, and so give a raw deal to the generation that follows. My argument was that tax policy can be used to offset this — e.g. 90% top marginal rates can shift this distribution without altering the total tax take, and such a policy would be good for aggregate demand as well.

Burk,

>But if high amounts of the debt were to be redeemed there, causing inflation<

I repeatedly see many variants of this statement, but it seems completely absurd to me. One day I'm risk averse having tied up my money in govt debt (less return than a savings account!) , the next day I'm on an inflationary spending spree? Really??

Dear RebelCapitalist at 12.03 am

You said:

While the current debate is focusing on bank reform etc the need to amend our distributional systems is being buried. It is absolutely essential that we bring real wages growth back in line with productivity growth and increase the wage share in national income as a result if we are to enjoy sustainable growth and not have to rely on boom-bust consumption spending driven by increasing private sector indebtedness.

How we get back to that sort of parity is not clear given the neo-liberal assault over last 3 decades has weakened the unions.

best wishes

bill

Dear Andrew at 8.54 pm

As I wrote in this blog – Quantitative easing 101 – QE is a portfolio shuffling exercise and does not directly add any stimulus. It is based on the false notion that banks lend out reserves. The only way that QE can stimulate demand is by reducing long-term investment rates and stimulating investment spending. It is highly unlikely that the lower rates will have that effect in the current climate where expectations of future demand and profitability are very low.

best wishes

bill

Dear KanucK at 10:27 pm

You said:

The government doesn’t have to admit to it if it happens. It is plain for all to see every time one of the “great unwashed” enters a shop during an inflationary period.

I also haven’t seen many governments lose authority during an inflationary episode.

best wishes

bill

Dear Ralph at 8.20 am

I have a PhD student who is soon to complete a thesis on this very topic and has a large collection of official documents amassed over time and released under 30 year laws which would suggest that government deliberately co-operated with capital to engineer rising unemployment to undermine the power of trade unions.

I would bet we could find similar evidence in many nations if we looked.

best wishes

bill

Dear Burk at 11:39 am

You said:

I actually don’t care much about the “resolution of debt”. Historically, the debt ratio has falling if economic growth is strong enough. I take your points that in the future as we come up against resource limitations, growth may be too slow to achieve this “resolution”.

But the problem we will face will not be how much debt there is. The government can always reduce the debt servicing payments by lowering the interest rate.

The problem will be the reduction in our living standards engendered by the declining resource availability. The government could also resolve its “debt issue” any time it wanted to. It could just stop issuing it.

best wishes

bill

Praise for Friedman’s column from Mark Throsby, associate professor of economics, here: http://economics.com.au/?p=5581

Dear JamesH

Just goes to show you would not want to study economics with him. His assessment of Friedman is totally uncritical and plainly misses all the important issues. Appalling.

best wishes

bill

Absolutely believable — and I hope you can post a note somewhere when the thesis becomes available. Government has a long history of trying to manipulate the financial markets in order to suppress wages and reward asset holders.