In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Britain and its fiscal rule death wish

Governments that adhere to the mainstream macroeconomic mantras about fiscal rules and appeasing the amorphous financial markets have a habit of undermining their own political viability. As Australia approaches a federal election (by May 2025), the incumbent Labor government, which slaughtered the Conservative opposition in the last election, is now facing outright loss to a Trump-style Opposition leader if the latest polls are to be believed. That government has shed its political appeal as it pursued fiscal surpluses while the non-government sector, particularly the households, endured cost-of-living pressures, in no small part due to the relentless profit gouging from key corporations (energy, transport, retailing, etc). The government has not been riven with scandals or leadership instability. But its amazingly fast loss of voting support is down to its unwillingness to take on the gouging corporations and also to claim virtue in the fiscal surpluses, while the purchasing power loss among households has been significant. The same sort of death wish is arising now in the UK, although the British Labour government is at the other end of its electoral cycle which gives it some space to learn from its already mounting list of economic mistakes. The British government situation is more restrictive than the case of the Australian Labor government because the former has agreed to voluntarily constrain itself via an arbitrary fiscal rule.

The latest economic data from Britain

The latest National Accounts data from the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) – GDP first quarterly estimate, UK: October to December 2024 (released February 13, 2025) – shows that the British economy is overall GDP growth was:

… 0.1% in Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2024, following no growth in the previous quarter.

Overall, real GDP growth was 0.8 per cent in the March-quarter, then 0.4 per cent in the June-quarter, then 0 per cent in the September-quarter, to 0.1 per cent in the December-quarter.

The production sector recorded negative 0.8 per cent growth for the December-quarter and negative 1.7 per cent for the year.

This was mostly due to contractions in manufacturing and mining and quarrying.

Business investment fell by 3.2 per cent in the December-quarter 2024 but inventories rose significantly (particularly in manufacturing).

The rise in inventories is considered to be unintended investment and reflects the declining outlook in sales – a negative signal.

Household consumption expenditure did not grow at all in the December-quarter.

Exports (volumes) fell by 2.5 per cent (all down to goods)

Taxes less subsidies fell by 0.8 per cent mainly due to a decline in VAT reflecting the stagnant activity levels.

Real GDP per capita fell by 0.1 per cent and 0.1 per cent over the course of 2024.

This measure has fallen 7 out of the last 9 quarters.

I thought this table from the special ONS article – Trends in UK real GDP per head: 2022 to 2024 – summed up the folly of the neoliberal period quite succinctly.

Interestingly, the ONS indicates that “long-term sickness” is one of the reasons for the decline in productivity growth, which has been part of the reason that GDP per capita has fallen and trailed behind overall GDP growth.

I have been following the COVID-related damage to the viability of the British labour force since 2020 and now we are starting to see some of the longer-term negative consequences of the lack of attention to this disease.

The next graph shows the government contributions to GDP growth in Britain since the September-quarter 2023.

The Government contribution is the sum of government consumption expenditure and government capital formation.

The ‘GDP net government’ line is just the overall GDP growth rate minus the contribution of government, which is an approximation because if we really set the government contribution to zero, then it is likely that non-government expenditure components would change (probably for the worse) and the overall GDP growth would be lower than what is shown in this graph.

But it is clear – since the Labour Party won office in Britain on July 4, 2024 – the overall GDP growth rate has been propped up by government expenditure.

In the December-quarter 2024, the government growth contribution was 0.29 per cent, and without it, the economy would have recorded negative growth.

Indeed, Britain would have been in recession in the second half of 2024 had the government contribution not been 0.13 percentage points in the September-quarter and 0.29 percentage points in the December-quarter.

The fiscal rule plank

The UK media are now claiming that the British government is now caught in a bind.

The UK Guardian article (February 15, 2025) – Rachel Reeves has three options to dodge an economic crisis and all are unthinkable – which followed the release of the latest National Accounts data in Britain suggests that all the options available to the Labour government carry massive political damage.

The hope expressed by the Chancellor when she took office in July last year was that her fiscal plans would be ratified by accelerating GDP growth now appears to be misplaced.

GDP growth is not accelerating as noted above.

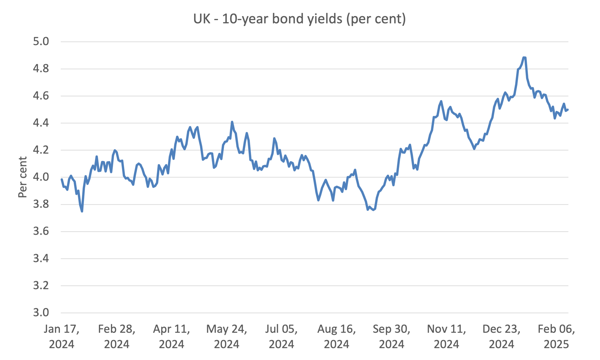

Further, the next graph shows that government bond yields have been rising since September 2024 although that trend has reversed since the onset of the New Year.

But it remains that the 10-year bond yield has risen from a recent low of 3.762 on September 11, 2024 to its current level of 4.499 per cent on February 14, 2025.

That sort of shift in apparent across the suite of gilt yields.

What that means is that the British government is spending more on servicing its outstanding debt than previously.

Also with GDP growth stalling, tax revenue has declined below what was expected.

The Chancellor was reported as saying she retained an “iron grip” on government spending (Source).

In the – Autumn Budget 2024 (released on October 30, 2024) – the H.M. Treasury claimed that:

The government is announcing robust fiscal rules, which the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) confirms the government is on track to meet:

– Stability rule: to move the current budget into balance so that day-to-day spending is met by revenues.

– Investment rule: to reduce net financial debt as a share of the economy.

It said the current fiscal balance is in “surplus by £9.9 billion in the target year, 2029-30”.

The forward estimates were predicated on estimated GDP growth of 1.1 per cent in 2024, 2 per cent in 2025, 1.8 per cent in 2026, 1.5 per cent in 2027 and 2028 and 1.6 per cent in 2029.

It also estimated that household consumption growth would be 1.7 per cent in 2025 and export growth would accelerate.

The £9.9 billion estimated fiscal surplus by the end of the current term of office (2029-30) is being touted by the media as the ‘fiscal headroom’ that the Government has – the leeway for slippage without compromising their fiscal rule pledge under the debt component.

The current trends noted above suggest that the growth forecasts will prove to be overly optimistic, which then compromises the fiscal outcome estimates.

In its most recent – Monetary Policy Report – February 2025 (released February 6, 2025) – the Bank of England has already downgraded their GDP growth forecasts and are predicting just 0.1 per cent in the first-quarter of 2025.

If that turns out to be accurate then it will be very difficult for Britain to achieve an overall 2 per cent rate of growth for 2025 as is assumed in the Autumn 2024 statement.

This UK Guardian article (February 15, 2025) – Rachel Reeves has three options to dodge an economic crisis and all are unthinkable – claims that the readers should understand the £9.9 billion projected fiscal surplus in 2029-30 as:

… spare money …

Implying that there is some limit on the sterling that the UK government has at its disposable.

The ‘limit’ is, in fact, totally artificial because it depends on a voluntary restriction on outcomes defined by the fiscal rules – as an absolute.

The current trends suggest that even if the ‘investment rule’ is not yet compromised, the ‘stability rule’ – that recurrent spending must be matched by taxation revenue – will struggle to be met.

The Guardian claims that this means in the context of the Spring Statement (at the end of March 2025):

Something has to give and soon.

And all of this is in the context of major upheavals in the global economy with the tariff uncertainty, the shifts in US support for Ukraine, and the proposed ‘real estate development’ on the sovereign Palestinian territory.

The three options that commentators are listing are:

1. Cut government spending “by more than planned already in real terms towards the end of this parliament”.

2. Increase tax rates “again”.

3. Abandon the artificial fiscal rules.

According to the Guardian, the Labour parliamentarians know:

… that all of them would be hugely damaging politically.

Of course, Options 1 and 2 are only listed because of the fiscal rules.

The British Treasury released a statement on January 8, 2025 claiming that despite these trends:

No one should be under any doubt that meeting the fiscal rules is non-negotiable and the government will have an iron grip on the public finances.

Already the financial markets are issuing threats of an “adverse market reaction” if Option 3 was chosen and that if a combination of Options 1 and 2 were not chosen then the Government “would risk a loss of confidence in financial markets”.

The same old.

Britain now has a classic case of a government that has tried to satisfy the mainstream economists and in doing so has constrained itself politically to the point that it only faces a very dangerous walk out on a very short plank.

The Chancellor has made too many guarantees – no further tax increases, no further austerity, and an ‘iron grip on the fiscal rules’.

And those guarantees were in the context of unrealistic growth forecasts.

Taking Option 1 and/or 2 would likely drive the economy into a deep recession, which would make it nigh on impossible to satisfy the fiscal rules.

A bind.

As I noted when Labour was in Opposition adherence to their fiscal rules would not be possible under a wide range of possible economic outcomes.

Those outcomes are present now which means the only way forward, if the Government really wants to avoid an austerity-driven recession is to abandon the fiscal rules and admit they were a folly in the first place.

The problem is that the Government has itself to blame for the situation it now faces.

By making these artificial and largely meaningless fiscal rules central to the public perception of ‘credibility’ and ‘fiscal responsibility’, the Government has conditioned the debate such that it can only fail.

There is no basis in economic theory for these rules.

They are arbitrary and place unnecessary constraints on government fiscal policy.

Why should recurrent spending be matched with tax revenue?

What is recurrent spending anyway?

For example, a lot of spending on education is classified as recurrent when it delivers long-term (beyond 12 months) benefits.

Salaries for nurses are recurrent but their work delivers long-term health benefits.

And so on.

Why should government debt ratios be lower after 5 years?

Why not 2 or 3 or 10 years?

Why is the current debt ratio too high, such that it must be lower in 5 years?

And so on.

Further, the financial markets are hawks.

The participants are motivated only by greed and are continually appraising the strength of government commitment to a course of action.

They know that the British government has cornered itself with the public and will fold if the financial markets put pressure on the currency with short-selling.

The markets thus know that they can bluff Reeves because she has bestowed such importance on the fiscal rules.

Conversely, the Japanese government (including the Bank of Japan) always resist these pressures and so the financial markets make losses on attempts to destabilise policy settings.

The Japanese government does not profess these hard and fast fiscal rules and thus doesn’t ‘box’ itself in to unsustainable positions.

The reality is that the financial markets have no real leverage over government if the government plays them out of the game, as happens in Japan.

The British government could just instruct the DMO (Debt Management Office) to stop issuing gilts if the yields at the auction process rose as the financial markets tried to flex their muscle.

They could force the Bank of England to purchase sufficient debt in secondary markets to drive yields to zero.

Conclusion

All of this mess that the Labour government is now finding itself rises because it has tried to be clever by holding out these artificial fiscal rules as a sacrosanct barrier beyond which civilisation ends.

They then have to reap the political failure that follows.

Another Labour government committing 切腹 (harakiri).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Other than the recent catastrophic but mercifully short tenure of the Liz Truss administration, I cannot recall such an inept and dysfunctional bunch of politicians that make up the current Labour government of Keir Starmer. Considering they had well over a decade in opposition to assess and consider the decline in British society and the economy, their first Q in power has been a disaster of their own ignorant making.

As a criminal barrister, Starmer has operated on the narrow evidential basis of trial procedure – only considering the evidence placed before the court and fitting it nicely into their own case in neat, easily attributed boxes for the jury to understand. Politics is rather different insomuch as there’s a necessity for considering the bigger picture – what Rumsfeld once called known unknowns and unknown unknowns. Thinking outside the box is not something Starmer is capable of. He is, literally, clueless.

The fiscal rules were always going to derail this Chancellor. Reeves had an opportunity on taking office, to explain to the public, how government spending and money creation actually worked – and what that offered and provided a progressive society. Instead she doubled down on Margaret Thatcher’s household budget analogy and derision of the Magic Money Tree (MMT) doctrine. The £22billion black hole was a prime example of her ignorance on fiscal reality.

It will not end well. HMS Britain has lost all navigation, power and is heading for the rocks in a perfect storm – whilst its crew’s experience is limited to playing with ducks in a bathtub.

Inability to see fiat spending power through the MMT lens is a systemic (structural) result.

As soon as I saw those fiscal rules I thought how soon the pitchforks would come out.

They will discover where the money is kept now that WW III is about to start.

Starmer stands for nothing beyond securing his position — first by defenestrating Corbyn and purging the Labour (in name only) Party of any opposition, then by changing its leadership selection process to prevent a repeat of the Corbyn phenomenon (which is to say, any actual grass roots democratic impulse). He evidently calculated that “the Fiscal Rule” was electorally convenient, given the dreadful state of the public discourse where macroeconomics is concerned — and events proved this calculation to be essentially sound, especially in the face of a Tory Party in utter disarray.

But now Starmer has to govern, and this is a very different challenge from either conducting a party coup or walking through an open electoral door — and the man is an empty suit. He is the hollow man. And now he discovers that “the Fiscal Rule” of such electoral convenience is actually in governance a straitjacket.

Oh well …

Today’s FT: “Japan’s GDP expands for third straight quarter and beats forecasts”

“the dreadful state of the public discourse where macroeconomics is concerned “.

There’s the rub. The current Labour government really have dug their own macroeconomic grave.

It evidently suits the banksters to maintain the fiction of the ‘household finances’ comparator, so we’re not going to see any advance on public understanding of fiat currencies from the mainstream.

Then the centre right simply follows the orthodoxy. British Labour have always feared the City. I believe even McDonnell had the same cautious mindset regarding the power of the financiers, so Labour is unlikely to challenge this without a lucid and forceful macroeconomist from the left emerging to gainsay the fairy tales of fiscal rules.

The foundations of neoliberalism have become embedded, in Gramscian mode, making political change much more difficult.

How the basic notions of MMT and the nature of fiat currencies are then diffused is restricted not only by the number of people who understand and can articulate the reality of money, but who has media access.

There are a few fairly isolated voices here in the UK so the raising of awareness is very slow.

I have noticed an increase in comments on fiat currency in ‘below the line’ discussions, but I’d guess that until the main public broadcasters and MSM are willing to explain its true nature, there will be little progress.

The BBC and Guardian seem particularly wedded to orthodoxy.

British Greens are still hung up on Positive Money’s committee to manage fractional reserve banking, and all the other parties with parliamentary representation are household financers.

I’ve seen a very weak rebuttal of MMT from Simon Wren-Lewis who represents the orthodox left, and Richard Murphy the accountant has a rising audience on YouTube, but is against the core MMT tenet of the ‘jobs guarantee’ and supports neither wealth taxes nor LVT as options for redistribution, only supporting taxes of flows and not stocks, though paradoxically supports the recent farmland tax reform.

Not sure Varoufakis has much of a regular UK following either, though he is capable of garnering an audience.

So we continue to lack access to a decent range of informed critiques of neoliberal dogma, and its now over 20 years since Steve Keen first published ‘Debunking Economics”.

It doesn’t concern me at all when the GDP of wealthy nations doesn’t rise as much as predicted. If I wanted to know how a country is performing, I’d be asking, “What is its labour underutilisation rate?”; “What is the distribution of its income and wealth and how is it trending?”; “What is the standard of, and how easy is it for people to access, public goods?”; “Are the benefits of what a nation is doing rising more or less than the costs of what it is doing? – i.e., are the net benefits of what a nation is doing rising or falling?”; What is happening to its Ecological Footprint and does it exceed its Biocapacity?”

If all of these are trending in the right direction and GDP is stagnating or falling, who cares? We should care as little about GDP as we should care about a currency-issuer’s budget bottom line and a nation’s GDP-deficit ratio, since GDP is a means to our ends.

Some people will say that you can’t achieve full employment and improve the lot of the poor without GDP growth. Firstly, if that’s the case, then we are in big trouble because GDP growth beyond a sufficient level, and especially beyond an ecologically sustainable level, is destructive. Secondly, it’s not the case once you do something to control population growth (the biggest elephant in the room). Distribution is the key. There is more than enough real stuff being produced to fully employ everyone who wants a paid job and ensure everyone can live a decent life – something that would be made easier if we introduced a Job Guarantee (not a Universal Basic Income) and confiscated unearned financial claims on real stuff, which we know there is plenty of because it’s the only way someone can be a multi-millionaire. We need to undo the neoliberal reconfiguring of economies, which are now systems based almost entirely on institutionalised chrematistics and plundering the planet.

Only in impoverished nations would achieving desirable goals likely involve some GDP growth and only until GDP reaches a sufficient level. GDP growth fetishes are every bit as bad as budget fetishes.

One way to compress Bill’s commentary is,

“Britain’s Exchequer is governed by LSE alumni.” Little more need be said.

Quite a bit of commentary from the public and academia regarding the British Chancellor’s addiction for growth. I thought this letter in today’s Guardian particularly incisive.

“Re your editorial (The Guardian view on Britain’s broken economy: ‘That’s your bloody GDP, not ours’, 13 February), we are frequently reminded of the inadequacy of GDP growth as an objective, given that it includes the money spent on dealing with pollution, sickness, crime etc. But nobody gets out of bed thinking, “I have to grow GDP today”. We’re thinking about how to earn a living and pay the rent. Nobody, that is, except the chancellor, for whom “growth is the No 1 mission” that “underpins everything else” – schools, hospitals, net zero.

Yet decades of growth since the 1960s have left us with thousands of food banks and facing an environmental abyss. The idea that only more growth will allow us to protect the planet is like saying we can only finance the fire brigade by selling petrol to arsonists.

Yes, our current economy to some degree counteracts the loss of jobs to automation by producing an ever-growing volume of stuff and persuading the better-off to want it. But even at this unsustainable level of consumption growth, the economy fails to provide much of humanity with life’s basics. Furthermore, since money can be made more easily out of addiction and dependence than out of restraint and self-sufficiency, much of the consumption growth consists of products with limited benefits or that are actively harmful to health, wellbeing and community life.

The challenge is to end catastrophic consumption growth while simultaneously enabling all of us, globally, to have the opportunity of a good life. That requires changing the economic rules, tackling inequality, taxing wealth not employment, and strong environmental regulation.

Donald Power

London “

“Yes, our current economy to some degree counteracts the loss of jobs to automation by producing an ever-growing volume of stuff and persuading the better-off to want it.”

Automation makes labour more productive. It reduces the number of labour hours required to produce and maintain a given stock of goods, which ‘ought’ to increase the number of leisure hours we can enjoy without reducing our material standard of living. I say ‘ought’ because automation is only a problem when the gains from increased productivity are not equally shared by labour and capital. When it was equally shared (pre-1983 in Australia), productivity rises increased real hourly wages and shortened the working week. The unemployment between 1974 and 1983 was the result of deficient demand not automation.

When the gains from increased productivity are equally shared, there is no need to produce more stuff because there is nothing lost to counteract.

Bijou wrote:

“One way to compress Bill’s commentary is, “Britain’s Exchequer is governed by LSE alumni.” Little more need be said.

Yes, and why is it so?

In my opinion: MMT did not explain, in the heady days a decade ago when MMT was actually being discussed in Congress during the passage of a bill to ban it (!), that:

1. currency-issuing governments can issue ‘government money’ without relying on ‘taxpayer money’.

AND

2. explain how the elected government could control inflation without hiding behind inflation control via unelected “independent reserve banks” setting monetary policy.

And the reason for this?

IMO, due to MMTers not facing the issue of allocation of resources via ‘invisible hand’ free markets, versus government management of resources for the good of all (…gasp…..”socialism”.)

Obviously everyone should be guaranteed access to the essentials, before the private sector competes for personal wealth accumulation via free markets.

But those ‘heady days’ mentioned above are apparently long gone, after the mainstream easily blew MMT away with the “printing money causes inflation” narrative.

Last week I attended an ALP meeting in which the guest speaker was a US Dem party official, ostensibly to give Labor some clues on how to win theupcoming Oz election (! ..despite the fact the Dems lost in the US…)

Naturally, a totally unenlightening talkfest in which the audience mostly condemned Trump and the media (and Joe Logan…) ; at the end I showed the US official ‘The Defict Myth’ to ascertain if she has heard of Stephanie Kelton…answer: “no”. (She took a photo of the book cover) .

So – after only a decade or so later, this young-ish woman had no knowledge of the controversies re MMT (in the years after the GFC), though she was aware of Bernie Sanders, whom she respected for his pro-‘working class’ policies ( though Bernie himself was never convinced by MMT, as we know…for reasons partly explained above?).

And even now I have to face arguments with MMTers about whether a currency-issuing government can issue ‘debt-free’ money.

Hopeless.