The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Bank of Japan research refutes the main predictions made by economists about the impacts of large bond-buying programs

Welcome to 2025. My blog recorded its 20th year of existence on December 24, 2024 which I suppose is something to celebrate. But when I look out the window and try to find optimism I fail. Who knows what the year holds and global uncertainty is dominating the narratives surrounding economic developments. We have a crazy guy about to take over the US along with his band of crazy guys. Government coalitions are failing all over the place and international cooperation is giving way to nationalism. We have Israel still slaughtering tens of thousands of innocent civilians using the equipment made available by the US and other advanced nations. Apparently opposing that slaughter makes one anti-semitic. I could go on. Those observations will clearly condition my thinking in the next year. But today, I am catching up on past work. On November 29, 2024, the Bank of Japan published a research paper – (論文)「量的・質的金融緩和」導入以降の政策効果の計測 ― マクロ経済モデルQ-JEMを用いた経済・物価への政策効果の検証 (which translates to “Measuring the effects of the “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing” policy since its introduction: Examining the effects of the policy on the economy and prices using the macroeconomic model Q-JEM” – the paper is only available in Japanese). The research uses innovative statistical techniques to assess the impact of the low interest rate, large bond-buying strategy deployed by the Bank of Japan between 2013 and 2023. The Bank of Japan research refutes the main predictions made by economists about the impacts of large bond-buying programs.

The Bank of Japan introduced its Quantitative and Qualitative Easing policy in April 2013.

You can refresh your memories about the QQE policy by reading this paper from the former governor of the Bank of Japan, Haruhiko Kuroda (October 8, 2016) – “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) with Yield Curve Control”: New Monetary Policy Framework for Overcoming Low Inflation (in English).

You might also like to read my own analysis here:

1. Q&A Japan style – Part 5b (December 5, 2019).

2. Q&A Japan style – Part 5a (December 3, 2019).

Those who follow Japanese economic policy shifts will know that the Bank of Japan has been trying to push the inflation rate up for many years.

The most recent attempt started on April 4, 2013 when the Bank of Japan announced they were resuming their program of Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE), which involves the Bank entering the secondary JGB market and more recently corporate debt markets and using its endless capacity to buy things that are for sale in yen, including government bonds and other financial assets.

They announced they would spend around “60-70 trillion yen” a year (see Statement Introduction of the “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing”).

On October 31, 2014, the Bank of Japan announced it was expanding the QQE program.

It would now “conduct money market operations so that the monetary base will increase at an annual pace of about 80 trillion yen (an addition of about 10-20 trillion yen compared with the past).”

Then on January 29, 2016, the Bank issued the statement – Introduction of “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with a Negative Interest Rate” – which augmented the QQE program – continuation of the annual purchases of JGB of 80 trillion yen and the application of “a negative interest rate of minus 0.1 percent to current accounts that financial institutions hold at the Bank”.

I considered that last decision in this blog post – The folly of negative interest rates on bank reserves (February 1, 2016).

Later (during the early COVID period), the Bank of Japan added support for corporations, which stopped share prices from falling.

QQE also saw the yen depreciate as central banks around the world hiked interest rates while the Bank of Japan held their policy rate constant.

Fiscal policy also remained expansionary, with the Government actually increasing its discretionary net spending to soften the cost-of-living pressures that arose from the supply-side induced inflationary pressures.

In March 2024, once the Bank was satisfied that the latest wage bargaining rounds were delivering an increased wage outcome and that this would see the underlying inflation rate rise towards their desired level, QQE was terminated.

All the mainstream pundits (including senior economists) predicted that inflation would accelerate and the bond yields would skyrocket because the government was effectively buying massive quantities of its own debt – which the mainstream claimed was ‘printing money’.

How wrong they were.

The inflation rate barely moved although there was a little spike in 2014, which followed the fiscal policy decision to hike the consumption tax rate.

That alone demonstrated the relative strength of each of the two aggregate policy instruments (monetary and fiscal).

And the explosion in yields clearly did not pan out as the moronic financial press had predicted.

The yields followed exactly the course that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) predicted – down.

The fact that the Bank of Japan was buying up government debt at its leisure clearly demonstrated that it is a monopoly supplier of bank reserves denominated in yen.

Fast track to November 2024, when the Bank of Japan researchers have now formally investigated all this using advanced statistical techniques.

The researchers used Q-JEM, which is the Quarterly Japanese Economic Model maintained by the Bank, to simulate counterfactual outcomes for key variables in the absence of the QQE policy intervention.

The write (translated):

The difference between the simulation results and the actual values of the economic and price variables was then measured as the policy effect.

How does Q-JEM allow for policy interventions to impact on real variables such as GDP growth and private capital investment and consumption expenditure?

The model is conventional and thus lower interest rates reduce costs of financing investment projects and housing purchases.

Also, the lower interest rates place downward pressure on the yen (via “the widening of the domestic and foreign interest rate differential”), which helps to stimulate demand for exports and boosts corporate profits.

I won’t discuss all the technicalities of the research methods here – I actually don’t want this blog to become a cure for insomnia.

The research concluded that:

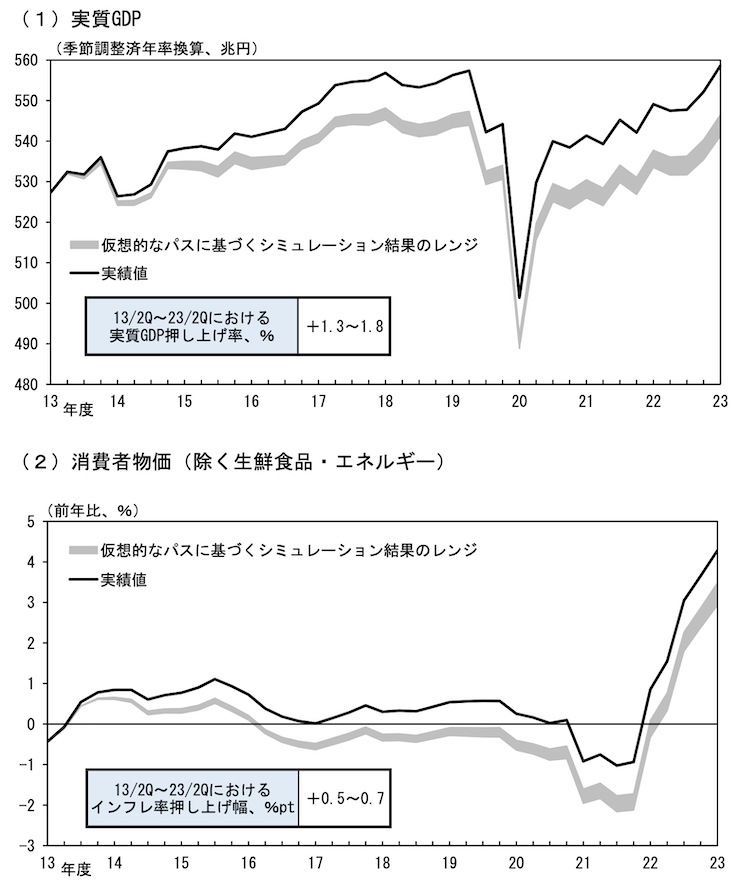

Looking at the average for the period since April-June 2013, the policy effect on the level of real GDP was +1.3 to +1.8% … and the effect on the year-on-year change in consumer prices was +0.5 to +0.7 percentage points. Looking more closely, the policy effect has cumulatively boosted the level of real GDP since the introduction of QQE, and has supported the economy even after the spread of COVID-19 infection in 2020. The rate of increase in consumer prices has been continuously boosted, and in the period since 2016, when the actual value declined due to the slowdown in emerging countries and the strong yen, the unconventional monetary policy has been effective.

This graph (Figure 7, Page 32) shows these results based on the actual and simulated values for GDP growth (top) and the inflation rate (bottom).

The thicker line is the simulated counterfactual path (that is, no QQE intervention).

The researchers also concluded that:

Given that the year-on-year change in consumer prices remained positive at less than 0.5% for much of the late 2010s, the latter result suggests that if the series of unconventional monetary easing policies had not been implemented, prices would have continued to fall for a long time during that period.

According to the modelling, the major reason that the QQE was supportive was through the impact of lower interest rates on capital investment and household consumption, particularly the former.

Taken at face value, the research demonstrates that the major predictions that mainstream economists made about the impacts of QQE were misplaced.

However, the research needs to be qualified because it ignores the impacts of fiscal policy.

The researchers acknowledge that they take fiscal policy as given and do not seek to isolate its own impacts on total demand.

They acknowledge that this ignores the interaction between QQE and fiscal policy, even though the QQE policy essentially meant that the Government could spend without having to divert any of that expenditure into interest payments.

In the case of 10-year bonds, the yield curve control aspects of QQE even delivered negative yields, which meant that the government was being paid by bond investors to sell them the financial assets.

And that lack of diversion meant that government spending could be more targetted.

Don’t take from this that the interest payments are an issue.

However, there are distributional impacts and during this period the corporations were sitting on massive retained earnings and the private banks, that historically have been the largest purchaser of Japanese government bonds (before the central bank took over) were not hoarding profits.

Conclusion

Anyway, all the best for 2025 as my blog enters its 21st year of operation.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

After the 2008 crash, vast quantities of wealth went from the the elites portfolios to the pockets of some hedge funds.

So, governments all around the world, went on a two tier aproach to recover the elites’ portfolios: austerity to the poor, to give it to rich; free credit for the rich to invest and build back the lost assets.

But, there wasn’t very much to invest in.

Only real estate stood as a viable option.

So, a real estate bubble started forming, until it got too big and threatned to bust.

In 2022, free credit was over, and there was interest to pay on trillions of credit given.

Someone had to pay and the bill went to the poor and became known as inflation.

Japan is the only country in the western world playing in the long run.

Everyone else is looking to their pockets.

“In the aftermath of the pandemic, the euro area labour market has shown remarkable resilience. Higher profit margins, lower real wages and lower average hours worked per employee have allowed firms to retain staff and keep hiring, despite weak economic growth.” – European Central Bank

https://x.com/ecb/status/1876192383140077724

It’s always so refreshing to see so-called elites celebrating the misery of the working class!

Glad Bill is back at it. Again I press the point that the old language of classical economics, based upon monetary scarcity, when used to talk about MMT, the new science of unlimited fiat money, inescapably distorts the new science and creates confusion. One small example in this blog post will suffice: “The fact that the Bank of Japan was buying up government debt….” A currency-sovereign country like Japan can have no debt, in the traditional sense, denominated in its own currency. It may have a legal duty or obligation to divert a portion of its inexhaustible stream of money in a certain direction, to a particular party, but all of the negative connotations of the word “debt” as used in classical economics, the onerous and constraining aspects involved in the borrowing and owing of money when money is limited, simply do not apply. Thus using such language in an MMT analysis usually requires some sort of immediate clarification or qualification in a two steps forward, one step back fashion. Is it not time that MMT had a “come to Jesus” moment and grasped the truth of the reported teaching that new wine must be put into new skins?

MMT posits a lens through which the concept of “debt” (as commonly understood) does not apply to the currency-issuing sovereign. Newton Finn is right (again).

The BOJ clearly understands its operations as liquidity management, not “buying up government debt.”

Application of the term “debt” to the currency-issuing sovereign is what prevents the public being able to see through the MMT lens.

What should be the term used?

The entire Government issued liabilities (including cash) can be considered Government “debt”, right? Though usually only interest earning Government liabilities are referred to as “debt”.

For some time, I have defined debt as a liability that, in order to extinguish, requires surrendering something that is tangible (real) and possesses some use value. Currency-issuers have financial liabilities, but no debts. They sell financial assets (bonds) to currency-users which in turn constitute the currency-issuers own financial liabilities. They give up nothing tangible with use value to extinguish these liabilities. They have 100% seigniorage.

The financial liabilities of currency-users are debts because they must give up something real with use value (sell their labour, a good or service, or a real asset) to acquire the currency in order to extinguish their liabilities. Currency-users have 0% seigniorage.

This way, I can disassociate currency-issuing central governments from debt, but highlight the problem of rising non-governmental debt.

Newton, John B. — I call Treasury bonds “future money”, created using the same machinery and out of the same thin air as any other form of fiat money. Government bonds and currency both are financial assets of the private sector and financial liabilities (debt) of the Government. Further, the practice of creating bonds and swapping them for currency has relevance under a convertible currency regime as a way to protect the Treasury’s gold supply. There is no compelling reason for bond issuance with fiat money, not even the lame excuse of monetary policy, given that the Government can pay interest on reserves.

Philip, your distinction between liability and debt seems a stretch.

There are three ways to resolve a debt. It may be written off or forgiven, it may be paid in kind (here’s that cup of sugar I borrowed last week, or here’s an ounce of gold for the month’s car payment) or it may be cancelled by an offsetting debt. Say I owe Bob a fiver, and Art owes me a fiver. I could give Art’s IOU to Bob and be clear. In daily commerce, the role of Art is generally played by an entity we call The First State Bank of Art, duly chartered and regulated, where I have a deposit (that is, the bank owes me money).

The Bank ultimately pays it’s debts with Government debt (paper notes or reserve liabilities owed to the Bank) and Government debt is valuable because when returned to the Treasury it cancels a tax liability.

All money is debt.

Creigh Gordon:

Let’s examine your three ways to extinguish a currency-user’s financial liability.

1) It may be written off or forgiven. If the creditor is a currency-user, it is the creditor and not the debtor who is giving up something real to extinguish (write off) the liability. If the so-called creditor is a currency-issuer (i.e., for some reason a tax-imposing currency-issuer writes off a currency-user’s tax liability), nothing real is given up, since the currency-issuer doesn’t receive (re-spend) any money when it taxes, and can spend its own newly-created base money into existence to obtain something real of the same monetary value as the written-off tax liability. Nothing real is ever foregone by a currency-issuer when it spends its own base money.

Result: Currency-issuer has 100% seigniorage – gives up nothing real to extinguish its liabilities (the liability is not a debt, as I have defined it); currency-user has 0% seigniorage – must give up something real equal to the value of the liability to extinguish the liability (the liability is a debt, as I have defined it).

2a) Payment in kind (e.g., cup of sugar and gold). Unless I’m mistaken, a cup of sugar is real with use value. Gold is also real, except it doesn’t have a lot of use value. Gold is bought and sold largely for speculative purposes, unlike cups of sugar, which is why gold has a much higher exchange value.

Result: A currency-user has 0% seigniorage – is giving up something real (sugar or gold) equal to the value of the liability to extinguish the liability. The liability is therefore a debt, as I have defined it.

2b) Offsetting liability. As a currency-user, you are now extinguishing a liability by surrendering a financial claim on real stuff. The liability is a debt, as I have defined it.

3) Bob, Art, and yourself. What the three of you are doing is extinguishing your liabilities (settling your debts), which happen to be of the same monetary value. But how did each of you obtain $5? As currency-users, you can’t obtain it in the same way as a currency-issuer. If it hasn’t been borrowed (which means you’d have to surrender something real in the future worth $5 to pay off the debt), then each of you must have surrendered something real in the present (or in the past) worth $5. In effect, you have all surrendered something real with use value to settle your liabilities (debts). The liabilities are debts, as I have defined it.

Conclusion: The financial liabilities of a currency-issuing central government are not debts, as I have defined debt (so long as the liabilities are denominated in the currency that the CICG issues). I agree with one of the comments that it is not helpful to label CICG liabilities as debts, especially when they are not. From conversations I’ve had with people taking an interest in MMT, labelling CICG liabilities as debts is confusing at best, and incorrect at worst.

There’s no question that money whether it’s government paper notes or reserves or bonds or commercial bank deposits is a liability of the issuing entity, it’s listed right on the liability side of their balance sheet. The question is can we call it a debt. I think any liability is potentially a debt, the difference is some kind of contingency: in the case of money the contingency seems to be that someone has to ask for payment. When the creditor has a right to call for payment and payment has not yet been made it is certainly a debt. This leads me to believe that the difference between these kinds of liability and what we would legitimately refer to as debt is trivial. Just calling it all debt is the simplest way to understand what’s going on.

Creigh Gordon: I can tell you, the difference between having to give up something real to extinguish a liability (currency-user) and not having to give up something real to extinguish a liability (currency-issuer) is not trivial. The difference between 100% and 0% seigniorage is not trivial. It’s the essentially the basis of MMT. Are you telling me that if you were offered currency-issuing powers, you’d knock them back because your circumstances would be trivially different?

In my opinion, the best way to highlight the important difference between a currency-user and a currency-issuer is to define a debt as a requirement to surrender something real to extinguish a liability and therefore say that the liabilities of the former are debts, and the liabilities of the latter are not debts. Apart from anything else, it would give the deniers of MMT less ammunition (not that they have much). No longer would it make sense to say that the accumulated deficits of a CICG is the National Debt; that bond-issuance, when labelled as debt-issuance, is tantamount to CICG borrowing; etc. When CICGs issue bonds, they issue financial liabilities, not debts. It is already difficult enough to convince people that CICGs have no financial constraint. It is made more difficult when CICG liabilities are referred to as debts, especially when they are not debts.

Money has value because the issuer owes delivery of a benefit whose value is specified in units of currency. The Government owes payment of its bonds in its currency, and it owes acceptance its currency as a tax payment. You could call these liability or you could call them debt, but for use as money it makes no difference. (Large financial institutions like banks and corporations can and do use bonds as wholesale money. Currency is more convenient at the retail level, but fundamentally the two things work the same way.) The easiest way to end the confusion would be to stop issuing bonds, which, as I mentioned above, is not necessary if there’s no gold supply needing protection.

Creigh Gordon: In the end, one can call CICG liabilities whatever they want. I prefer to leave it as ‘liabilities’. The fact remains that a CICG does not have to give up something real to extinguish its liabilities. For that reason, I believe CICG liabilities are not debts. A currency-user does have to give up something real to extinguish its liabilities. For that reason, I believe the liabilities of currency-users are debts. There is a fundamental difference between what is required of a CICG and a currency-user to extinguish their liabilities, This difference, and the implications it has for any financial constraint that a CICG or currency-user might have (the former has no constraint; the latter does), is made clearer by defining debt in the manner I have, especially given the connotations of the word ‘debt’.

‘debt’ – bad

but

‘risk-free debt’ – good

so

‘government risk-free debt’ = good

use/talk/write/discuss/use ‘risk-free debt’ = good debt

Dan: My distinction between a liability and a debt has nothing to do with which one is good and which one is bad, or whether they are good or bad. The distinction highlights the fundamental difference between a currency-issuer and a currency-user. To extinguish a liability, a currency-user must surrender something real. A currency-issuer doesn’t. The implications of this in terms of the ability to access real resources in a monetary economy cannot be overstated. As I said in response to Creigh Gordon, would you knock back currency-issuing powers if you were offered them? That is, would you knock back the ability to access real stuff you desire without having to surrender real stuff you desire less or no longer desire, an ability you don’t have? I don’t think so.

What makes a currency-issuer’s liabilities ‘risk free’, which you say is ‘good’, is that the currency-issuer doesn’t have to acquire/possess real stuff to extinguish its liabilities. I’d go so far as to say that a ‘risk-free debt’ is an oxymoron. There are ‘risk-free liabilities’ (nothing real has to be surrendered to extinguish the liabilities) and ‘risk-associated liabilities’ (something real must be surrendered to extinguish the liabilities), where the latter are debts and the former are not.

You obviously don’t agree with me, but I believe that referring to the financial liabilities of a currency-user as ‘debts’ is not helpful and is unnecessary.