I am travelling today to Tokyo and have little time to write here. But with…

Australia national accounts – government expenditure saves the economy from recession

Today (December 4, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest – Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, June 2024 – which shows that the Australian economy grew by just 0.3 per cent in the September-quarter 2024 and by just 0.8 per cent over the 12 months (down from 1 per cent). That growth rate is well below the rate required to keep unemployment from rising. GDP per capita fell for the 7th consecutive quarter and was 1.5 per cent down over the year. This is a rough measure of how far material living standards have declined but if we factor in the unequal distribution of income, which is getting worse, then the last 12 months have been very harsh for the bottom end of the distribution. Household consumption expenditure was flat. The only source of expenditure keeping GDP growth positive came from government – both recurrent and investment. However, fiscal policy is not expansionary enough and at the current growth rate, unemployment will rise. Both fiscal and monetary policy are squeezing household expenditure and the contribution of direct government spending, while positive, will not be sufficient to fill the expanding non-government spending gap. At the current growth rate, unemployment will rise. And that will be a deliberate act from our policy makers.

The main features of the National Accounts release for the September-quarter 2024 were (seasonally adjusted):

- Real GDP increased by 0.3 per cent for the quarter (0.2 per cent last quarter). The annual growth rate was 0.8 per cent (down from 1.0).

- GDP per capita fell by 0.3 per cent for the quarter, the 7th consecutive quarter of contraction. Over the year, the measure was down 1.5 per cent – signalling declining average income.

- Australia’s Terms of Trade (seasonally adjusted) fell by 2.5 per cent for the quarter and were down by 3.9 per cent over the 12 month period.

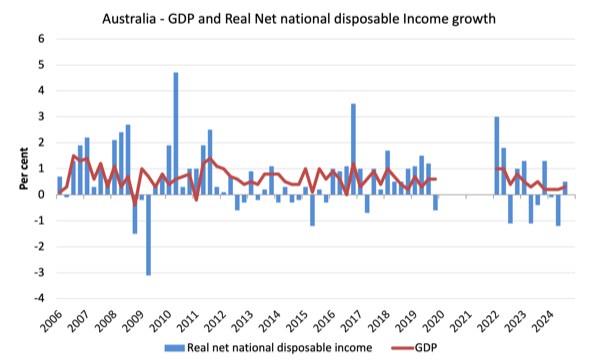

- Real net national disposable income, which is a broader measure of change in national economic well-being, rose by 0.5 per cent for the quarter and 0.4 per cent over the 12 months.

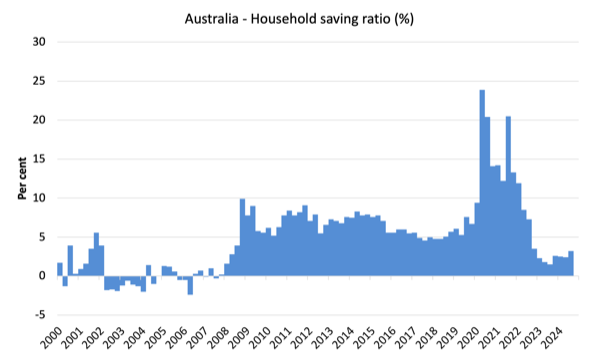

- The Household saving ratio (from disposable income) rose to 3.2 per cent (from 2.4).

Overall growth picture – growth continues at much slower rate

The ABS – Media Release – said that:

Australian gross domestic product (GDP) rose 0.3 per cent in the September quarter 2024 and by 0.8 per cent since September 2023 (seasonally adjusted, chain volume measure …

… The Australian economy grew for the twelfth quarter in a row, but has continued to slow since September 2023.”

The strength this quarter was driven by public sector expenditure with Government consumption and public investment both contributing to growth.

GDP per capita fell by 0.3 per cent, falling for the seventh straight quarter …

Public investment rose 6.3 per cent in the September quarter …

Household spending was flat in the September quarter following a fall of 0.3 per cent in June …

The household saving ratio rose to 3.2 per cent in the September quarter …

The short story:

1. The weakness in private domestic demand is pushing the economy towards recession and the only buffer against that decline is the government sector and we learned yesterday that “total public demand is expected to contribute 0.7ppt to the quarterly change in GDP” as the fiscal position moved from surplus to deficit (Source).

2. We also learned yesterday that the trade surplus has almost evaporated and the overall external position recorded a rising deficit ($A14.1 billion) as a result of the net primary income deficit of $A17.3 billion) (Source). Further, the “$0.8 billion rise in net trade (seasonally adjusted, chain volume measure) is expected to add 0.1 percentage points to the September quarter 2024 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) movement.”

3. There was no growth in household consumption expenditure.

4. Private investment expenditure growth is very modest (plus 1 per cent for the quarter and mostly due to new dwelling construction.

5. The growth in government spending was mostly due to the energy rebates designed to reduce the cost-of-living pressures arising from the price gouging that the privatised energy companies have indulged in over the last several years. The government is refusing to deal with the companies directly and prefers to give them a subsidy so that the burden on households and the political fallout is reduced.

6. Import expenditure fell due to flat consumption growth (particularly falling demand for electric vehicles).

7. However, given the decline in non-government spending growth, the current fiscal settings are way too restrictive and when combined with the tight monetary settings, it is clear that the Government, overall, is deliberately sabotaging the material well-being of millions of Australians under the veil of ‘fighting inflation’, which would have returned to pre-COVID levels anyway, without the austerity.

8. That point is demonstrated by the on-going per capita recession which masks how bad things are given the highly skewed income distribution (the top-end of the distribution are not bearing the burden).

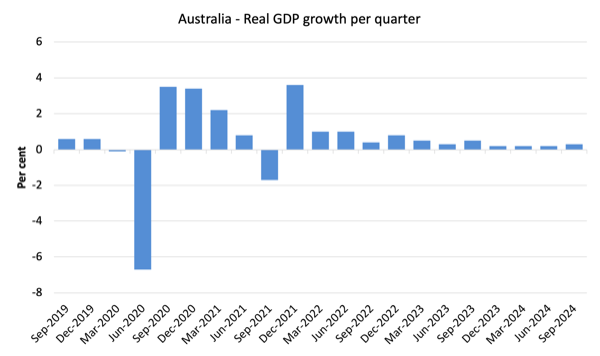

The first graph shows the quarterly growth over the last five years.

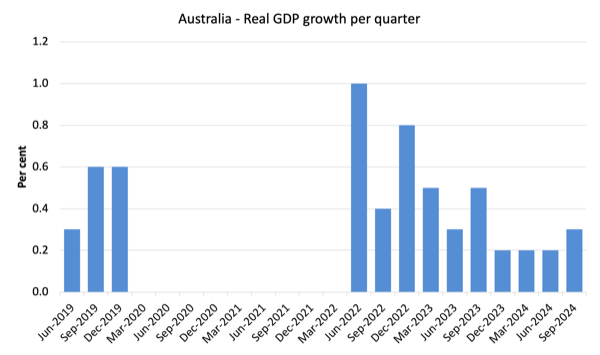

Here is the same graph with the extreme observations during the worst part of the COVID restrictions and government income support taken out.

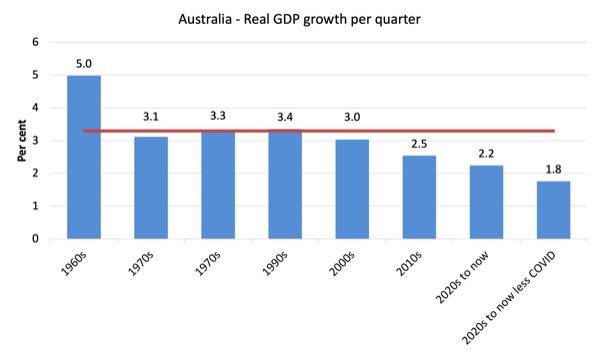

To put this into historical context, the next graph shows the decade average annual real GDP growth rate since the 1960s (the horizontal red line is the average for the entire period (3.26 per cent) from the March-quarter 1960 to the September-quarter 2024).

The 2020-to-now average has been dominated by the pandemic.

But as the previous graph shows, the period after the major health restrictions were lifted generated lower growth compared to the period when the restrictions were in place.

If we take the observations between the September-quarter 2020 and the September-quarter 2022, then the average since 2020 has been 1.8 per cent per annum.

It is also obvious how far below historical trends the growth performance of the last 2 decades have been as the fiscal surplus obsession has intensified on both sides of politics.

Even with a massive household credit binge and a once-in-a-hundred-years mining boom that was pushed by stratospheric movements in our terms of trade, our real GDP growth has declined substantially below the long-term performance.

The 1960s was the last decade where government maintained true full employment.

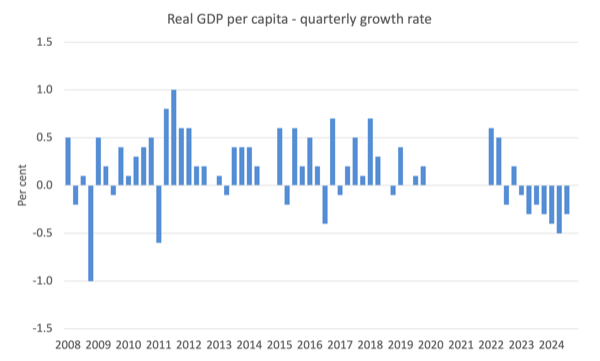

A GDP per capita recession – deepening

GDP per capita fell for the 7th consecutive quarter, which means that total output averaged out over the entire population contracted for the last 21 months of 2023.

Some consider this to be a deepening recession although what the average actually means is questionable.

With the highly skewed income distribution towards the top end, what we can say if the average is declining, those at the bottom are doing it very tough indeed.

The following graph of real GDP per capita (which omits the pandemic restriction quarters between September-quarter 2020 and December-quarter 2021) tells the story.

Analysis of Expenditure Components

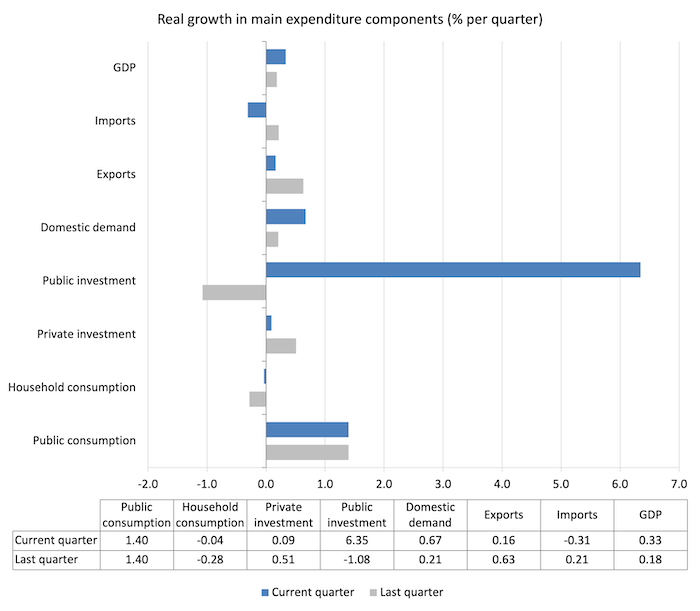

The following graph shows the quarterly percentage growth for the major expenditure components in real terms for the June-quarter 2024 (grey bars) and the September-quarter 2024 (blue bars).

The contribution of government investment and consumption expenditure saved the economy from recession in the September-quarter 2024.

Contributions to growth

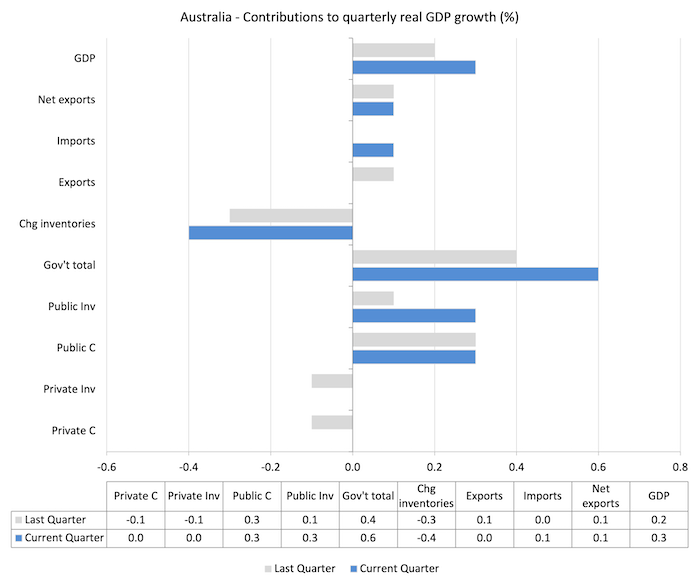

What components of expenditure added to and subtracted from the change in real GDP growth in the September-quarter 2024?

The following bar graph shows the contributions to real GDP growth (in percentage points) for the main expenditure categories. It compares the September-quarter 2024 contributions (blue bars) with the previous quarter (gray bars).

The standout is the contribution of the government sector – both recurrent expenditure (0.3 points) and capital expenditure (0.3 point).

Without that it is likely household consumption growth would have contracted even more than it did and the economy would have entered a GDP-recession.

Material living standards rose in September-quarter and for the year overall

The ABS tell us that:

A broader measure of change in national economic well-being is Real net national disposable income. This measure adjusts the volume measure of GDP for the Terms of trade effect, Real net incomes from overseas and Consumption of fixed capital.

While real GDP growth (that is, total output produced in volume terms) rose by 0.3 per cent in the September-quarter, real net national disposable income growth rose by 0.5 per cent.

How do we explain that?

Answer: While the terms of trade fell by 2.5 per cent in the September-quarter, “Compensation of employees (COE) increased 1.4%” and “Gross disposable income rose 1.5% as gross income rose and income payable fell.”

Household saving ratio rose to 3.2 per cent from 2.4 per cent

The RBA has been trying to wipe out the household saving buffers as it hiked interest rates hoping that this would reduce the likelihood of recession.

Of course, that process has attacked the lower-end of the wealth and income distribution, given the rising interest rates have poured millions into those with interest-rate sensitive financial assets.

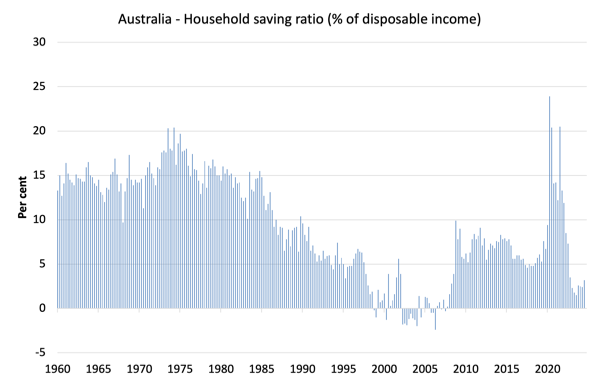

The following graph shows the household saving ratio (% of disposable income) from the December-quarter 2000 to the current period.

It shows the period leading up to the GFC, where the credit binge was in full swing and the saving ratio was negative to the rise during the GFC and then the most recent rise.

The current position is that households are being squeezed by a combination of rising living costs, elevated interest rates and low wages growth, which is forcing households to reduce their savings rate to maintain expenditure on essentials.

The next graph shows the saving ratio since 1960, which illustrates the way in which the neoliberal period has squeezed household saving.

Going back to the pre-GFC period, the household saving ratio was negative and consumption growth was maintained by increasing debt – which is an unsustainable strategy given that household debt so high.

Households are now cutting back on consumption spending and that will ultimately drive the economy into recession unless the government support continues at increasing levels.

The following table shows the impact of the neoliberal era on household saving. These patterns are replicated around the world and expose our economies to the threat of financial crises much more than in pre-neoliberal decades.

The result for the current decade (2020-) is the average from June 2020.

| Decade | Average Household Saving Ratio (% of disposable income) |

| 1960s | 14.4 |

| 1970s | 16.2 |

| 1980s | 11.9 |

| 1990s | 5.0 |

| 2000s | 1.4 |

| 2010s | 6.7 |

| 2020s on | 8.9 |

| Since RBA hikes | 3.0 |

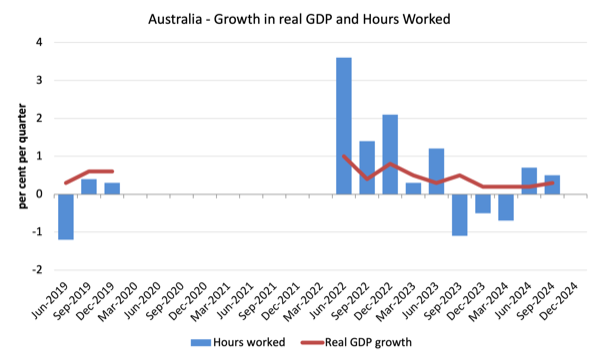

Real GDP growth rose but hours worked rose more and productivity growth declined

Real GDP rose 0.3 points in the quarter, while working hours rose by 0.5 per cent.

Which means that GDP per hour worked fell by 0.4 points for the quarter – that is, a decrease in labour productivity.

Over the last 12 months, productivity growth averaged -0.7 per cent on the back of weaker output growth and stronger hours growth.

The following graph presents quarterly growth rates in real GDP and hours worked using the National Accounts data for the last five years to the September-quarter 2024.

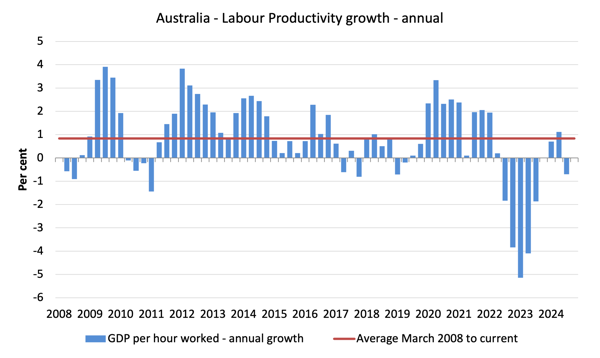

To see the above graph from a different perspective, the next graph shows the annual growth in GDP per hour worked (labour productivity) from the September-quarter 2008 quarter to the September-quarter 2024.

The horizontal red line is the average annual growth since the March-quarter 2008 (0.8 per cent), which itself is an understated measure of the long-term trend growth of around 1.5 per cent per annum.

The relatively strong growth in labour productivity in 2012 and the mostly above average growth in 2013 and 2014 helps explain why employment growth was lagging given the real GDP growth. Growth in labour productivity means that for each output level less labour is required.

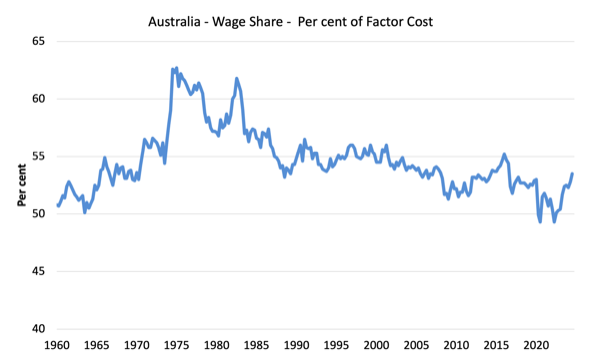

The distribution of national income – wage share rises slightly

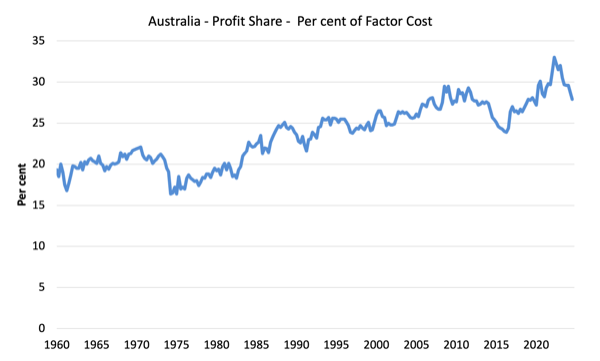

The wage share in national income rose to 53.5 per cent (up 0.7 points) while the profit share fell to 27.9 per cent (down 0.9 points).

The difference is the rise in the government share.

The first graph shows the wage share in national income while the second shows the profit share.

The declining share of wages historically is a product of neoliberalism and will ultimately have to be reversed if Australia is to enjoy sustainable rises in standards of living without record levels of household debt being relied on for consumption growth.

Conclusion

Remember that the National Accounts data is three months old – a rear-vision view – of what has passed and to use it to predict future trends is not straightforward.

So in the September-quarter, the Australian economy remains just out of recession after growing by 0.3 per cent.

The only source of expenditure keeping GDP growth positive is coming from government – both recurrent and investment.

The largest component of national expenditure – household consumption spending – was flat.

However, fiscal policy is not expansionary enough and at the current growth rate, unemployment will rise.

Overall fiscal policy and monetary policy are squeezing household expenditure and the contribution of direct government spending, while positive, will not be sufficient to fill the expanding non-government spending gap.

And that will be a deliberate act from our policy makers.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The focus on Australia’s aggregate and per capita GDP over the past 24 hours indicates how much we have confused means with ends. Why don’t the following get the same attention: (a) Australia’s labour underutilisation rate? (b) the distribution of income (Gini coefficient) and wealth in Australia? (c) the real value of the Australian minimum wage? (d) Australia’s housing affordability index? (e) Australia’s suicide rate? (f) Australia’s homelessness rate? (g) Australia’s mental illness rate? and (h) Australia’s aggregate and per capita Ecological Footprint relative to its aggregate and per capita Biocapacity?

I might sound like a broken record, but if we are doing better with regard to the things above and per capita GDP falls, who cares? The only ‘losers’ would be the very rich, who, with a near-zero marginal benefit of consumption, would lose nothing but their power and feelings of superiority.

If we have to increase GDP to lower the unemployment rate (or, preferably, to achieve and maintain full employment), we will end up fully employing ourselves to ecological oblivion. There is no reason why full employment can’t be achieved with a lower per capita GDP. It all comes down to redistribution, which would best be achieved by taxing the rich and providing liveable incomes to the poor through guaranteed employment (e.g., a Job Guarantee), not a UBI. For reasons above, the rich won’t be worse off and because most of their ‘income’ is effectively ‘economic rent’ (unearned), they’ll keep doing what they are presently doing and be rewarded for the portion of what they do that is productive, which isn’t much in a lot of cases. No-one is worth more than about $500K per year. If the very rich don’t like it, they can emigrate and leave the real resources they currently have excessive claims upon to productive and useful Australians, thus making the job for governments easier. If you don’t mind me being facetious, Australia’s average IQ and per capita productive capacity might rise in the process!

I agree with Dr Lawn. Reducing full-time hours to four days per week would also help. The issue is: what is the maximum sustainable size of a nation’s economy? And how do we fairly distribute goods and services among the population (where the latter needs to stabilise and then probably reduce).

If the productivity gains over the last 40 years had been equitably shared, it might have been possible by now to have reduced full-time work to four days a week.