In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

The 20 EMU Member States are not currency issuers in the MMT sense

For some years now (since the pandemic), I have been receiving E-mails from those interested in the Eurozone telling me that the analysis I presented in my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – was redundant because the European Commission and the ECB had embraced and was committed to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) so there was no longer a basis for a critique along the lines I presented. I keep seeing that claim repeated and apparently it is being championed by MMT economists. While there are some MMTers who seem to think the original architecture of the Economic and Monetary Union has been ‘changed’ in such a way that the original constraints on Member States no longer apply, I think they have missed the point. They point to the fact that the ECB continues to control bond yield spreads across the EU through its bond-buying programs (yes) and that the Commission/Council relaxed the fiscal rules during the Pandemic (yes). But the bond-buying programs come with conditionality and the authorities have now ended the ‘general escape clause’ of the Stability and Growth Pact and are once again enforcing the Excessive Deficit procedure and imposing austerity on several Member States. The temporary relaxation of the SGP rules (via the general emergency clause) did not amount to a ‘change’ in the fiscal rules. Indeed, the EDP has been strengthened this year. The Member States still face credit risk on their debt, still use a foreign currency that is issued by the ECB and is beyond their legislative remit, and are still vulnerable to austerity impositions from the Commission and their technocrats. To compare that situation with a currency-issuing government such as the US or Japan or Australia, etc is to, in my view, commit the same sort of error that mainstream economists make when they say that ‘the UK is at risk of becoming like Greece’ or similar ridiculous threats to discipline fiscal authorities in currency-issuing nations.

There are various interrelated questions that bear on this subject.

The first relates to whether the debt that is issued by a government is subject to credit risk or not.

A government that issues debt to the non-government sector through bond market auction mechanisms (usually) is not subject to credit risk if it can always meet the liabilities when the debt matures – that is, has to be repaid.

The choice of mechanism is not really the issue, nor is the capacity of the central bank to purchase the debt directly rather than through the secondary bond market – that is, after it has been issued to the primary market dealers, who ‘make the market’ – that is set the yields on the issued debt release.

The question is simple enough – is there are situation where the issuing government would not be in a position to meet the outstanding liability?

If the answer is no, then we think of that government as a sovereign currency issuer.

If the answer is yes, the opposite conclusion applies and that is irrespective of whether the particular government creates reserves in the commercial banking system when it spends.

The German government, for example, creates reserves in the banking system when it spends but its debt is subject to credit risk, unlike, say the Australian government, which similarly creates bank reserves when it spends, but faces no credit risk on the debt it issues.

The clear difference between these two governments is that the German government uses the euro, while the Australian government issues the $AUD.

Using a currency is different to issuing it.

Marc Lavoie understood this difference clearly in his 2022 journal article – MMT, Sovereign Currencies and the Eurozone – which was published in the Review of Political Economy (Vol 34, No 4, pp 633-646).

He is not an MMT economist although he wrote that “I agree with 93% of MMT” (the 93 per cent being a reference to George Stigler’s 1958 article – Ricardo and the 93% Labor Theory of Value, which was published in the American Economic Review, Vol 48, No 3, June 1958).

Marc Lavoie quoted from my 2015 book in clarifying the point:

… the bond investors know that the EMU nations face insolvency risk because they have to borrow to fund their commitments. In the absence of any ECB support, these nations are reliant on the terms set by the bond markets for any debt that they issue …

That statement was on page 196 of my book.

Marc Lavoie concludes that this is the “appropriate answer”:

… bond markets knew or thought that the ECB would not act as a purchaser of last resort for the governments that would be under the attack of speculators. It has not much to do with the common currency as such. It is more a matter of operational reality — the convention that the ECB and the national central banks of eurozone countries would not do any outright intervention on secondary markets.

Even though we are close on the matter, I disagree with his point that it has “not much to do with the common currency as such”.

Of course it is based on that reality – because if the Greek government could spend beyond its tax revenue without having to seek funds from the bond markets then it would never have been destroyed by the GFC.

Sure enough, it was not helped by the ECB which refused to buy its debt to stabilise yields until a comprehensive bail out plan was put in place – read nation destroying set of conditions.

But the root cause was that it could not run a deficit until it funded that deficit from the bond markets and the bond markets wanted higher and higher yields to compensate for the increasing credit risk.

It might be said that many nations that have their own currencies face similar difficulties because they have rules or laws that prevent the central bank from directly funding the fiscal deficits.

But that also misses the point.

Those governments have the legislative or regulative capacity to alter those voluntary constraints whenever they see fit and thus can avert a crisis from occurring.

The 20 Eurozone Member States cannot individually legislate to command the ECB to do anything.

The currency-issuer in the Eurozone, which has all the financial power of a central bank anywhere, is restricted in its capacity by the Treaties that define and govern the common currency.

Those treaties are not the legislative or the regulative creation of the individual Member States to vary at their individual pleasure.

The second issue arose during the early years of the Pandemic, when the European Commission invoked the emergency clauses in the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), the fiscal rules framework that details the latitude (or lack of it) that the Member States face when crafting their fiscal policy stances.

The emergency clauses effectively suspended the rules framework, in particular the operation of the – Excessive deficit procedure (EDP) – which:

… is a mechanism designed to ensure that EU member states return to or maintain discipline in their governments’ budgets … To limit government deficit and debt, member states have agreed reference values, which they have enshrined in the EU treaties: a 3% deficit ratio and a 60% debt ratio. The ratios are always calculated relative to a member state’s GDP.

The lesson from the GFC was that even the automatic stabilisers could force the fiscal outcome for a particular nation to violate the 3 per cent rule.

That is, the economic downturn was so bad that the tax revenue loss and increased welfare spending automatically pushed the fiscal balance beyond the 3 per cent threshold, without the government taking any discretionary action at all.

During the GFC, the breaches of the fiscal limits invoked the harsh austerity policies under the EDP, which ravaged prosperity in many Member States.

With the onset of the Pandemic, no-one really had a clue what the World was facing and governments and ruling authorities such as the European Commission (and Council) were cautious and relaxed the fiscal rules for a period.

Some MMT economists have since claimed that the decision to relax the SGP amounts to ending the Maastricht Treaty restrictions and effectively restores currency sovereignty to the individual Member States.

A recent article by Ehnts and Wray in the Review of Political Economy – Revisiting MMT, Sovereign Currencies and the Eurozone: A Reply to Marc Lavoie – asserts that:

… while there was a problem with the original set-up of the Euro system, this has been resolved in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the more recent COVID pandemic.

I disagree completely with this assessment.

The authors go on to say that:

The 2020 Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP), which has been replaced by the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), came straight out of MMT logic. As long as the ECB acts as dealer of last resort in government bonds, national governments will not lose access to their national central banks which make payments for and on behalf of the governments by crediting the reserves of banks that then credit accounts of recipients.

They point to Mario Draghi’s statement in July 2012 that “the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” as the tipping point where the Eurozone Member States became more like the US federal state than a US state, under the rules of the European Treaties.

Operationally, they claim that it meant that the ECB would ensure that no Member State government would become insolvent.

But this was quite a different pledge to the normal operational actions of a central bank say in Australia or the US during a deep crisis, which ensures, for example, that the commercial banking system doesn’t collapse or that large-scale government assistance generally can proceed.

For example, during the early years of the pandemic, the RBA purchased a large proportion of the debt issued during that period by the Australian government.

But it did not require anything in return.

The difference with Draghi’s ECB interventions, which really began pre-Draghi in May 2010 with the introduction of the Securities Market Program that stabilised bond yield spreads in the early crisis period, was that the ECB demanded harsh conditionality in return for buying the government bonds of the Member States.

And, it refused to purchase the Greek government bonds under the earlier versions of their bond-buying programs (which evolved over time using an array of descriptive names) because the Troika wanted to destroy any resistance to austerity.

Even in June 2015 when the country voted against continued austerity, the ECB did the unthinkable (for a central bank) and threatened the financial viability of the Greek banking system unless the government rejected the peoples’ vote, which of course it did.

When the Tsipras Syriza government – parading as a Left-wing government – embraced harsh austerity under the – Third Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece – they are recognising that the ECB would enforce insolvency of the entire financial system to ensure the Troika achieved its objective of keeping the nation within the common currency.

So there is a world of difference between the ECB buying government bonds in the secondary bond market and effectively ‘financing’ the fiscal deficits of Member States and the RBA buying Australian government bonds in the secondary bond market during the early period of the pandemic.

The authors then say that:

The pandemic finally lifted the truly constraining constraints: the reluctance of the ECB to act as dealer of last resort and relaxation of the deficit limits found in the Stability and Growth Pact.

The ECB was never really reluctant to purchase the Member State debt in secondary markets.

Once it was confronted with the GFC reality and it knew that the flawed architecture of the common currency meant that it was inevitable some of the nations (including Italy, which was the biggest fear) would face insolvency, it adopted its fiscal role and then papered over the fact that it was acting in violation of the ‘no bail out’ clause (Article 123) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, by claiming that the bond purchases were just liquidity management operations.

Of course, the scale of the bond purchases were multiples of what would be required for orderly ‘liquidity management’ operations, but as long as they kept saying it the pragmatic elements in the policy hierarchy (Commission, Council etc) could look the other way.

But as noted above, the intervention was not ‘free’ and required the Member States to engage in harsh austerity under the EDP rules which in many cases devastated the prosperity of the citizens affected.

It is obvious that the ‘relaxation of the deficit limits’ during the Pandemic has also given the Member States some latitude that they didn’t have during the GFC.

The reality is that many governments were reluctant to use the latitude sufficiently to prevent negative outcomes because they feared that the ultimate adjustments that would be required when the EDP rules were enforced again and the emergency clause terminated would be worse than if they maintained their fiscal outcomes within the normal SGP thresholds.

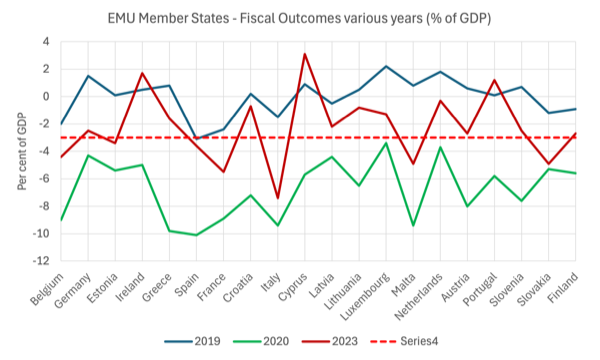

The following graph shows the fiscal behaviour since 2019.

The authors characterise the post pandemic situation as:

… the ECB once again assumed the role of dealer of last resort … and the European Commission changed rules so that national governments could use fiscal policy to address macroeconomic problems.

As a matter of clarity:

1. The ECB did not ‘once again’ assume the role – it has maintained a bond-buying program continually since mid-2014 (although the SMP introduced in May 2010 predated the current versions).

See – Asset purchase programmes – for more details.

2. The Commission did not change rules during the pandemic.

It just invoked a clause within the existing rule.

That difference in characterisation is crucial.

The Commission/Council did not abandon the SGP.

It did not abandon the surveillance mechanisms.

It did not abandon or deactivate permanently the EDP rules.

Indeed, since April 30, 2024, the “EU’s new economic governance framework” has been strengthened – in its austerity bias (Source).

The new framework, is just a new iteration of the SGP rules and related procedures.

1. The Commission informs the Council that the Member State is in breach of the 3 per cent limit.

2. The Council deliberates and adopts the Commission’s adjustment process for rectification.

3. The Member State has 6 months to introduce the austerity.

4. Failure to do so invokes sanctions scaled to GDP which must be paid every 6 months the nation is in default of the fiscal rules.

5. “The member state concerned does not have a vote” in these deliberations.

None of those procedures tells me that the EMU has turned the corner into a new world of fiscal freedom at the Member State level.

The ECB may continue to control spreads but it will be lock-step with Brussels in enforcing these rules.

Further, the authorities have now ended the general escape clause:

Due to COVID-19, the EU suspended its budgetary rules for all member states between 2020 and 2023 by activating the general escape clause. As of 2024, the general escape clause is no longer in effect. The EU has therefore relaunched the deficit-based EDP process under the new rules of the revised economic governance framework.

Already:

On 26 July 2024, following the Commission proposal, the Council adopted decisions establishing the existence of excessive deficits for Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland and Slovakia.

And:

Under the new rules, all member states need to prepare national medium-term fiscal-structural plans. These must contain a net expenditure path.

So to characterise the temporary relaxation of the SGP during the pandemic as a new era for the EMU which reflects “MMT logic” is far-fetched.

The intent in Brussels (and I have close contacts with officials there) and among the Eurosystem of central banks (again close contacts) is that the rules-based system will be enforced as it has been since the inception.

The ECB did announce a new version of its bond-buying programs, the so-called – Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) – which replaced the – Pandemic emergency purchase programme.

The conditions under the TPI are clear:

1. “compliance with the EU fiscal framework: not being subject to an excessive deficit procedure (EDP), or not being assessed as having failed to take effective action in response to an EU Council recommendation under Article 126(7) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).”

2. “absence of severe macroeconomic imbalances: not being subject to an excessive imbalance procedure (EIP) or not being assessed as having failed to take the recommended corrective action related to an EU Council recommendation under Article 121(4) TFEU.”

3. “fiscal sustainability: in ascertaining that the trajectory of public debt is sustainable”.

So the bond-buying support of the ECB continues (masquerading as a normal monetary operation) but so does the conditionality and none of the Member States can change the conditions unilaterally or together, for that matter.

The pandemic relaxation was a temporary aberration in the EMU’s relentless neoliberal pursuit of austerity.

The climate emergency may invoke a further relaxation.

But that does not represent a fundamental change in the fiscal status of the Member States.

They remain currency users subject to strict fiscal rules that are not democratically derived.

Finally, it was interesting that the authors in dealing with Marc Lavoie’s point that “there is a disagreement within MMT on the answer to the question” (about whether the Member States are sovereign and currency issuers) only refer to a few MMT offerings and only refer to my 2015 book in a footnote:

What Mitchell (2015) wrote about the Euro is consistent with our view. Once you understand that the euro is a supra-national currency, it becomes clear that joining the Eurozone was indeed a problem given the setup while it is still true that the bond market is impotent for nations that issue their own currency, for instance. As we have seen, the Eurozone can be reconfigured so that the bond market is impotent for a supranational currency as well.

I disagree.

Saying that the bond market is impotent in the EMU as long as the ECB acts to stabilise yield spreads while ignoring the fact that the ECB also simultaneously required harsh austerity misses the point of my 2015 work.

The question is would the ECB still act in that way if the national government refused to reject the conditionality (austerity)?

Well we know the answer: No, just look at what they did with Greece in 2015 when the people rejected the austerity and the ECB effectively forced the nation to the brink of insolvency.

Conclusion

There is thus fundamental disagreement among MMT economists about the Eurozone.

You can work out which side you are on.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I saw in awe the Portuguese ex-Prime Minister (and now to be the head of the european council) saying to a crowd (and to the television) that the vassal states of the EU are not forced to do anything by the comission of the blob.

He said that those countries (meaning small countries) voluntarily accept and enforce all those policies that hurt their people, their economy, their soberanity and their FREEDOM.

I wanted to ask him: what’s the difference? What if we don’t accept it voluntarily? What happened in Italy? Didn’t Berlusconi resigned – voluntarily?

I suspect it is not so much giving up a nation’s central bank that is the issue, but giving up the physical equipment on which a nation’s clearing system operates.

Which means that Italy and Germany (and possibly Spain) are in the driving seat because, unlike with Greece, they have the power to turn the ECB’s computers off – or at the very least separate it from the rest of the ECB system to run the national central bank.

All a Euro member has to do to get clear of the Euro is remove the one-to-one peg from the national central bank balance sheet to the one at the ECB.

One business we could divert the UK financial sector into is providing full blown clearing systems for EU member states denominated in their bonds. Then when a member state wishes to leave the ‘Euro standard’ they could do – just like the US coming off gold.

Thanks for this piece.

I am so sick of hearing that now the Eurozone and the ECB are “operating” under and MMT framework while I witness the permanent austerity and pettiness of our governments, the return of fiscal rules, the celebration of déficit reductions, and the obscene levels of unemployment that keep destroying lives, that reading someone stating the obvious is appreciated.

The ECB is not buying government debt any longer. The governments are reducing spending and raising taxes.

Rules, rules, rules. If you don’t like our rules, here is another set of rules.

Bill writes:

“They remain currency users subject to strict fiscal rules that are not democratically derived”

Why do I, as an Australian citizen, feel that the Oz government is “subject to the same strict fiscal rules which are not democratically derived” ?

Which is why Labor is in trouble , and today a Dutton minority government was mentioned as a possibility after the next election.

Of course the average punter think the government’s budget is the same as his/her own household budget, so “democracy” is moot….

The situation of EMU national governments is like the situation of state and local governments in the US and presumably that of local governments under other currency regimes — MMT as such does not apply.

The UK still operates as if it is a currency user. A foreign currency called Sterling, over which it has no control; regardless of which ideology is running the government. Alas, the chances of the UK ever introducing a US style “Inflation Reduction Act” are zero. Today, the UK’s tabloid media is getting in a tizz about how much UK debt is held by foreigners, both government and non-government. If you invest in foreign currency assets, you are the one taking the risk, not the foreign country.

The ECB is a Central Bank with no single Sovereign EU Treasury to create and spend Euro currency units, so it has to do both jobs. The EU should look to the US model where its member states are Dollar currency users under a federal government Dollar issuing Treasury. Sadly, I see only terminal decline for the EU and the UK in this embedded group-think mode.

@Gordon Creigh,

If the treasury of a currency-issuing government issues ‘debt’ (money created out of thin air) , to whom is the debt owed?

@Neil Halliday

But treasury doesn’t mess around with bank reserves, right. Central Bank does. Treasury issues debt to the Central Bank so that it can obtain Government money.

It shouldn’t need to with a Sovereign currency issuing Government which is why MMTers call for ‘funding’ deficits without Treasury debt. The Treasury should be able to go to the Central Bank and ask for the money it needs without any debt, its literally the same Government.

Ehnts & Wray ” … we conclude that while there was a problem with the original set-up of the Euro system, this has been resolved in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the more recent COVID pandemic….. We agree with Marc Lavoie that the fiscal framework is the real constraining factor explaining the weak macroeconomic performance…” & “The pandemic finally lifted the truly constraining constraints”

It seems the authors of the paper did not not consider other unchanged (and just as significant) structural constraints built in to the EU governance architecture.

I agree with Bill that the fiscal constraints are not ‘lifted’ – just temporarily bypassed to address an emergent crisis – however the other socially destructive issues of EU economic governance remain unresolved.

Is not Brussels (legislated!) ban on proper financial federation (horizontal equalisation) and industry allocation capacity also a truly constraining constraint?

All Eurozone states are financially unfederated by intentional design – Brussels cannot, and is precluded from providing member ‘states’ with horizontal equalisation grants on a state needs basis, or to allocate/facilitate private/supranational government investment to address regional unemployment levels, local resource availability, or social/health needs, or efficiency of supranational service delivery.

Nothing has fundamentally changed – the Eurozone remains a bickering dysfunctional social/economic disaster – by intended design.

@Sidharth,

Thanks. There is certainly a lot of confusion re public ‘debt’ among MMTers.

Kohler wrote recently that MMT “doesn’t give permission” to the currency-issuing government to fund itself with ‘free’ money (taking account of the *resource* constraint, of course – which is the issue which should concern treasury, not debt)..

He said MMT is merely a description of how the money system works , and is satisfied that “everyone knows deficits don’t matter” now – except politicians, the media and the population, a reality which he apparently hasn’t noticed…..

Neil, the Government used to owe you the right to either exchange your currency for gold or use it as a tax payment. Now it only owes you the right to use it as a tax payment.

Historically, the Treasury issued (non-convertible) bonds as a way to protect its gold supply. The currency used to purchase the bonds couldn’t be presented to the Treasury for conversion to gold, and the interest paid on the bonds, which was market determined, was motivation and reward for bond buyers assuming the risk that the Treasury would still be offering conversion when the bond matured. Without the offer of conversion, bonds are really just “future money”, “printed,” if you will, out of the same thin air and using the same machinery as current money.

Creigh,

Thanks for the history lesson.

But, given the dysfunction of the current global financial system, with debt crushing many poor nations; and a cost of living crisis even in a land of plenty like Oz; and given that money is created out of thin air – whether in commerical banks or a nation’s treasury – then new financial arrangements are necessary.

That’s why I posed the question: ‘to whom is treasury ‘debt’ owed?’. As observed by Sidharth:

“The Treasury should be able to go to the Central Bank and ask for the money it needs without any debt, its literally the same Government.”

We need a better system of *resource mobilization* that doesn’t depend on taxes and/or selling bonds to people who have money to spare.