I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Being objective … and lying rodents

Today there were two feature articles in the Australian press which attracted attention. The first article was an interview with the former Australian prime minister (Howard), who (by the way) was called a “lying rodent” by one of his own colleagues during his time in office. The second article was by the Sydney Morning Herald’s political editor who claims the Time has come for Rudd to face the big test. Both articles carry the same messages which are relevant to the macroeconomic debate in all nations (so this is not a parochial Australian discussion). They also nonsensical pieces of fiction when you consider them from the perspective of modern monetary theory (MMT). They show the power of the mainstream macroeconomics “textbook straitjacket” which has the world debate in a vice-like grip.

Objective: adjective 1. not influenced by personal feelings or opinions. 2. not dependent on the mind for existence; actual.

Neutral: adjective 1. impartial or unbiased. 2. having no strongly marked characteristics.

Just in case, you think using the English Oxford is biased, here is the Webster’s definition:

Adjective

1. Undistorted by emotion or personal bias; based on observable phenomena; “an objective appraisal”; “objective evidence”.

2. (grammar) serving as or indicating the object of a verb or of certain prepositions and used for certain other purposes; “objective case”; “accusative endings”.

3. Emphasizing or expressing things as perceived without distortion of personal feelings or interpretation; “objective art”.

4. Belonging to immediate experience of actual things or events; “concrete benefits”; “a concrete example”; “there is no objective evidence of anything of the kind”.

Clear enough. Apparently not.

First, the very popular textbook The Principles of Economics by Mankiw (I am referring to the first edition here) covers some of the issues raised by today’s articles in Chapter 25. In fact, the underlying economics that is expressed by the Peter Hartcher (in the Sydney Morning Herald) and the former Prime Minister is developed in textbooks like this.

In Chapter 25, we read how mainstream economics analyses “the effects of a budget deficit”. We will trace this through to tie the journalism to some body of “theory”.

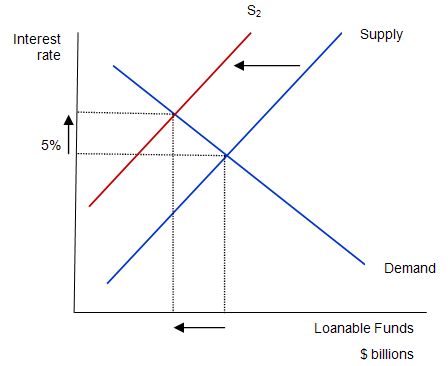

First, using the loanable funds model, Mankiw says a budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds which pushes up the interest rate because there is an excess demand at the old interest rate.

He tells his students that a “budget deficits lowers national saving”. This is step one in his on-going deception of the students. So a budget surplus is constructed as an increase in national saving. The diagram is reproduced from his Figure 25-4 on page 555).

Where is this alleged saving stored? I invite all of those who read this blog who are sceptical of MMT to do some research. Write to the treasuries and central banks in your nation and ask them to tell you where the “national savings” derived from a budget surplus are stored.

You can traipse all over Washington, London, Canberra, Tokyo or wherever you like and you will not find hide nor hair (which I discovered today is now the reverse meaning of the Old English term).

The point is that there is no saving. It is nonsensical to construct a government that is sovereign in its own currency as saving it. Budget surpluses go no-where – they are accounted for as a net drain of financial assets by some accountants but there is no stockpile of funds waiting to be spent at a future date.

Further, a surplus undermines private saving by squeezing private purchasing power relative to the taxation obligations levied in the unit of account (the currency). Conversely, budget deficits stimulate private saving by increasing national income.

Mankiw also claims that:

because the budget deficit does not influence the amount that households and firms want to borrow to finance investment at any given interest rate, it does not alter the demand for loanable funds.

Quite apart from the totally inapplicable concept of “loanable funds”, it is highly likely that a deficit will underpin higher levels of private confidence and encourage investors to resume building productive capacity – because they become more certain that they will realise revenue from production that would be forthcoming from the new capacity.

Allowing an economy to wallow in pessimism is the last thing a government should be doing. And the only way it can get the economy back to “health” is to net spend if private spending has collapsed or is being withdrawn.

Mankiw then explains why the supply of loanable funds contracts. Remember in MMT there is no credible concept of “loanable funds”. It assumes a finite pool of saving and the money multiplier exists – neither mainstream concepts have any applicability to a modern monetary economy.

He concludes the supply shifts left (as shown in the diagram) because:

… when the government borrows to finance its budget deficits, it reduces the supply of loanable funds available to finance investment by households and firms.

This is step two in his on-going deception of the students. First, the government voluntarily imposes the constraint on itself that it issues debt to match its net spending. There is no financial need for it to do so.

Second, even though it imposes this constraint on itself, it only borrows back what it has already spent and added to bank reserves. Would it still be able to spend if it didn’t borrow. Of-course, it spends in the same way irrespective of what else it does by way of monetary operations – it credits bank accounts.

It does not spend by printing money – ever! Any commentator who tries to argue that it does will have to demonstrate it operationally (don’t even bother trying) for me to accept the comment.

If they don’t accomplish the impossible (demonstrate governments spend by printing money) and they still tell us that governments are printing money then I will delete their comment and refer them to the mint statistics to verify that the government does print currency notes but that has nothing to do with its spending via fiscal policy.

Mankiw then draws his fabrications to date into the point he wants to make. This is step three in his on-going deception of the students.

… this higher interes rate … [from the deficits] … then alters the behavior of the households and firms that participate in the loan market. In particular, many demanders of loanable funds are discouraged by the higher interest rate. Fewer families buy new homes, and fewer firms choose to build new factories. Teh fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out … That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate (emphasis in the original).

Mankiw (page 557) also includes the following Robert Weber Cartoon (which was first published in The New Yorker on March 27, 1989). The inclusion is associated with his discussion of the “chronic problem for the U.S. economy” that he claims the Reagan and Bush deficits engendered. Of Reagan he says “… he was committed to smaller government and lower taxes. Yet he found reducing government spending was to be more difficult politically than reducing taxes.”

So the cartoon is meant to introduce negative emotions among the tens of thousands of students that are forced to use this textbook around the World.

But from a MMT-perspective the cartoon works well to illustrate that when there is a deficiency of aggregate demand brought on by a desire of the private sector to increase their saving ratio and a failing confidence among investors, the only way that the government can ensure that output and employment do not fall is to increase its net spending by crediting bank accounts.

This in turn becomes a deficit-reduction dynamic because as the private confidence recovers and consumers start to spend a bit more and investment starts to grow again, the automatic stabilisers built-in to the budget process go to work and start reducing the budget outcome. That is, tax revenue starts to rise and welfare payments decline.

Governments are also able to withdraw, if they like, some of the stimulus measures they may have introduced, although the ease that that can be accomplished depends (politically) on how well they were designed in the first place.

Finally, the other point MMT would tell us is that it is futile to have a deficit-reduction plan unless you are approaching full real capacity in the economy and want to avoid over-heating the economy. Even then, you may want to keep the deficit at whatever size it is and start cutting back private spending capacity by increasing tax rates.

The increased tax rates do not fund the deficit – they just reduce the spending possibilities for the private sector. The government would do this if it wanted less private spending without compromising public spending.

And now back to today. Sydney Morning Herald writer Peter Hartcher says this of himself on his home page:

In 27 years working for the Australian Financial Review and The Sydney Morning Herald he has developed a reputation as an authoritative, rigorous, nonpartisan reporter and analyst.

Non-partisan = objective and neutral as above.

His Wikipedia entry says that “Hartcher has been cited as one of the most objective opinion-setters in the country in a 2007”. What does objective mean anymore?

This assessment was apparently based on him being listed as being closer to Marx than Thatcher on the Bias-o-Meter at Crikey, the latter which in need of some better calibration one would think after reading his weekly neo-liberal (uninformed) bleeding.

When all you do is repeat the mainstream economics textbook mantra which may have been applicable during the gold standard era (and even that is questionable) and lace your journalism with ideological biases/fears about the dangers of governments and continually feed the prejudices of those who use socialism and government in the same sentence (unless it is a conservative government selling everything off to the rich or handing out cash to the top-end-of-town) – then you have to question the attribution of the term objective?

Here is how Hartcher began his piece today:

No one doubted that the Government could spend the money to buy 12 new submarines and 100 new combat aircraft. Spending is easy.

But could the Government wring serious savings out of the portfolio to help pay for it?

So you are introduced to the world of government budget constraints immediately as if there is no issue. Yes spending is technically easy – the government just credits bank accounts.

No, the government doesn’t need to “pay for it” other than in the sense that the spending absorbs real resources which are the “cost” and have to be available to facilitate the spending.

The government may decide it wants to keeps its net spending constant in which case it would reduce spending elsewhere (“wring serious savings out of the portfolio”) but that has nothing to do with “paying for the spending”. The last concept is totally inapplicable in a fiat monetary system.

Hartcher then continues this aberrant theme:

Spending taxpayers’ money is easy. Saving is hard. The Rudd Government was exceptionally lucky to inherit government with no net debt and with a $19.7 billion surplus in the federal budget.

It was lucky, first, because it meant that Australia was almost unique among the rich countries of the world in being so strongly financed. It was lucky, second, because it was not any national inevitability but a whim of personalities that allowed it to happen.

The inheritance of the zero net debt position has had no bearing on the current government’s capacity to pursue a stimulus program in the face of the global economic crisis. Nothing at all!

It also didn’t inherit any “money in the bank” as a result of the surpluses that the previous national government ran. In fact, those surpluses so undermined public infrastructure that our future growth prospects were reduced.

They also pushed the private sector into record levels of indebtedness that the need for deficits is now greater than it might have been given the private sector is now trying to repair its balance sheet by increasing the household saving ratio.

If the previous government had not have run those surpluses, it is highly likely that household balance sheets would be in better shape now and unemployment and underemployment would have been lower.

Hartcher then says that the former Treasurer:

Costello managed to put some money aside, unspent, as surpluses. If there had been a less assertive treasurer, or a less prudent one, Australia would have had a very different national fate.

As I argue above (and below) there was no “money put aside”. Surpluses or deficits occur on an hourly basis. In the case of a surplus, at each accounting period the national government credits bank accounts (spends) by less than it is debiting bank accounts (collecting taxes).

The impact is to squeeze the private sector of purchasing power as the government net drains financial assets from the non-government sector. There is no van that goes around collecting “money” and taking it to some vault for later use. That is a total misrepresentation.

I am sure Hartcher knows that there was no stockpile of money which makes his journalism more culpable – it takes it from being dumb bias (that is, errors which support the neo-liberal ideology that arise from omission and ignorance) to being deliberately biased (that is, deliberately false writing that supports the neo-liberal ideology).

Neither are acceptable, the latter requires he be dismissed.

Hartcher then descends even further into the myth-making:

… This was the third way in which Australia was exceptionally lucky. Because when the global recession hit, we were one of the very few countries in the world with enough cash in the bank for the Government to be able to use it decisively as a recession-buster. Almost uniquely among the advanced economies, Australia was not constrained by debt worries.

Proportionately, the Rudd Government spent more to fend off recession than any of the rich countries in the Group of 20.

Britain and Germany spent the equivalent of 1.6 per cent of their total economic output, or GDP, on stimulus this year, a comparison of stimulus spending published this week by the International Monetary Fund shows, while Canada spent 1.9 per cent, the US spent 2 per cent and Japan 2.4 per cent.

Australia? We outspent them all, outlaying 2.9 per cent of GDP for 2009. Canberra’s spending is fully half as much again as the average for the rich countries in the G20.

First, the reason that Australia is better off at present is because we net spent more and earlier. An unambiguous success for the fiscal initiative and should forever silence the neo-liberals who claim fiscal policy is ineffective.

Second, the capacity to do this had nothing to do with fiscal position the Rudd Government inherited. All sovereign governments could have done the same independent of their accumulated debt going into the crisis.

It is one of the major misrepresentations to suggest that there was “cash in the bank” that allowed the Rudd government the space to act. There was no more money in the Rudd fiscal policy capacity than there was in any country. There is no financial constraint on any sovereign spending which means theoretically it could infinitely credit bank accounts at any time it chose.

It would not be economically prudent to do that but financially it could.

Third, there was no “cash in the bank” as I explained above.

Hartcher then focuses on the future:

For the Rudd Government … [spending] … was the easy part. The hard part is upon it: to rebuild the budget, to rebuild a surplus, and not to piss away the national future on populist spending to get re-elected.

But which lesson will they learn? Will Rudd and Swan learn the narrow political lesson of the Howard “nightmare” and try to spend as much as they can get away with?

Or will they learn the bigger lesson, the lesson of the national interest, and put rigour into the national budget?

What the hell does this mean? What exactly is the “national future”? My take is that the government’s primary responsibility is to ensure total output is sufficient to fully employ the available workforce; to ensure that public infrastructure is the best that is available and equitably distributed; to ensure education is equitably-accessed and person’s potential is wasted; to ensure first-class public health care is available to all; and to make sure this all happens within an environmentally sustainable way.

If they followed Howard’s route and try to run surpluses they will undermine all these responsibilities.

The only way the economy can grow if the government sector is running increasing surpluses and there is not a large current account surplus (not the slightest bit likely) is if the private domestic sector increasingly goes into debt. That is the failed growth strategy we followed over the last 15 odd years and it was always destined to fail.

It is an unsustainable growth strategy. Doesn’t Hartcher understand that the private sector cannot go into increasing levels of debt indefinitely? At some point they will try to resume saving and then things will unwind and the government will find itself in deficit anyway – except this will be a bad deficit – with none of the quality infrastructure and modern skills to show for it.

Hartcher then addresses the trade question and says that with “China and India … [set to boom again] … their demand for Australian minerals will create a mining boom without parallel in Australian history … [which will cause] … wrenching change … In stark layman’s terms, Australia faces the prospect of returning to our industrial structure of a century ago – as a quarry and a farm.”

Well in trading terms we are still not much more advanced than that anyway. We export very few manufacturing goods and our tourist industry is about 3.7 per cent of total GDP. More significantly, outbound spending by Australian tourists typically exceeds inbound spending by foreigners (Source: Source).

But the point he wants to make about government budget policy is captured as follows:

How then to manage an income flow that is higher on average, over a long period, but potentially more volatile? Other countries have faced this challenge and met it. When Norway discovered oil, it set up a fund in the 1960s to save the windfall revenues against the day when the oil would run out. The fund today has some $US400 billion.

When Chile ran into the commodities boom of this decade, as Australia did, it set up two reserve funds in 2006 to accumulate the windfall revenues from a soaring copper price. Those funds today hold about $US17 billion.

The volatility of this foreign-sourced income flow does not change the capacity of the national government to pursue its socio-economic program. It does mean that the budget deficit will be smaller at times via the automatic stabilisers.

But the important point that Hartcher doesn’t grasp is that it is not about revenue. It is the state of aggregate demand that the government has to manage – it never has to worry about revenue.

So if we get to the point that net exports are driving aggregate demand growth (and typically they do not) then as in Norway, the government may have to run a surplus to keep aggregate demand growth in line with real production capacity.

But that will be a relatively easy thing to manage because it will have high levels of employment and high quality public infrastructure. Australia currently has neither. Norway always has had both – independent of its recent resource discoveries.

So the sovereign fund issue is a side-show. Let us get to full employment with first-rate broadband infrastructure, the best health system that is technologocially available; first-class dental care for everyone including indigenous Australians; first-class universities and schools; best practice water and land-use management protocols ….

and … let’s get rid of the Coal industry and reform farming so it doesn’t is carbon neutral C02.

Then if there is a need for a sovereign fund … we can talk about it.

Prediction: we will still need government deficits.

That last prediction is based on my objective understanding of MMT and my biased view that full employment and equity is better than high unemployment and inequality.

But Hartcher does not separate the two because he has not real understanding of how the monetary system operates – and in choosing to repeat what defunct economists recite from textbooks he is just passing on their ideological biases – word for word.

And now to the lying rodent …

A lying rodent never changes its spots …

On a related theme, today’s article in the The Sunday Telegraph – I’d stop the boats: Howard – reminds us of why Australia is so lucky it tossed out the last conservative government. Not that the current government is much better – a small improvement one might say.

In an interview with The Sunday Telegraph, former Prime Minister (aka the lying rodent) said that the current government “has wasted the nation’s savings” by moving the federal budget into deficit.

The lying rodent (former PM) was quoted as saying:

The Rudd Government comes up very short. I can’t think of a major thing it has done, except spend the bank balance that Costello and I left behind. Nothing else …

Mr Rudd will say he had the global financial crisis to handle. Well, courtesy of us he was well endowed with money in the bank.

There was “no money in the bank”. The previous government ran 10 surpluses in the 11 years we were unfortunate to have them in office. Towards the end of their tenure as the bond markets were drying up (they had retired the debt) they created the Future Fund, which involved the government speculating in financial assets (that is, spending on various speculative assets) instead of providing for public infrastructure that was, by then, starting to decay badly.

The idea that these surpluses created savings “money in the bank” is preposterous. I wonder if the ex-PM (aka the lying rodent) could tell us the address of the bank that the “cash” was held in?

He might say the Future Fund was “the bank”. First, it is a funny way to save … buying speculative assets, some of which have lost value significantly. The question Howard should answer is was the purchase of these assets the best thing for a country which was running down its education system (witness the current spate of collapses in the privatised education system); its public health system; its road and transport systems; and lagging behind the rest of the developed world in IT infrastructure provision, to name some elements of neglect that were magnified under his rule.

Second, and more importantly, the national government does not need to store up cash to spend in the future (unlike a household). The current government (as does any national government that issues its own currency) always has the capacity to spend whatever it has done in the past. There was no money in the bank because that is not the way the government operates in a financial sense.

The national government is not a household and the textbooks that pretend otherwise are fatally flawed and should be mulched and use on community gardens that will have to spring up everywhere when we start to dismantle the food industry monopolies that have turned food into something different – at our expense.

And … sorry to the rats … they don’t deserve to be tarred with an association to the so-called lying rodent …

PS: The interview was more about the shameful asylum seeker policies that both the past and present government are pursuing – and as the debate goes at present it was – a sort of “who can be the meanest to the boat people seeking refuge” contest. It makes our nation look pitiful and mindlessly xenophobic but that is another story for another day.

That is enough for tonight.

Sorry to put a further downer on this but I caught a snippet today of a British treasury official expressing concern that the British governments spending could soon lead to “government risking insolvency”.

This bloke was apparently a high level economic advisor to the British government.

Hi Bill

“No cash in the bank”, I tried explaining this to someone by stating taxation destroys money and is a way of sucking out excess liquidity in the system. It is however difficult to explain that tax(revenues) do not physically exist. Any pointers?

Dear Lefty

Poor Britain. Conservative to the end.

best wishes

bill

Dear pb

In Australia, employers take out tax as part of the monthly pay system for most workers (Pay As You Earn). So the workers gets a net amount electronically debited to their bank accounts and the employer electronically transfers the tax component to the Australian Tax Office (ATO) bank account. When PAYE instalments are deficient – for example, you earn some other income where the employer does not deduct a PAYE component (like for most consulting contracts), the person gets an assessment from the ATO (a letter) at the end of the financial year and then has to pay the ATO via an electronic transfer of funds to Australian Tax Office bank account any funds that are owing. Similarly, if the PAYE instalments exceed the assessed tax bill, the ATO debits your bank account (or equivalent – sends you a cheque) for the amount they owe you.

In each case the transactions are straight non-government to government sector electronic transfers (or exchanges of bits of paper that get recorded electronically).

When you pay the government – either via PAYE or otherwise – nothing physical gets transferred. The transactions are important and are accounted for and your liability is extinguished but the government receives nothing physical that it stores (that is, money).

In the USA, my colleagues tell me that taxes are also paid over the counter at post offices. Australia used to have this sort of system (with stamps) some 40 odd years ago. They also tell me that all tax transactions made in this way – which might involve a person handing over greenbacks in return for a receipt are then dealt with by the Federal Reserve in the following way. They come around to the collecting offices in a truck, collect the greenbacks – having already received an electronic accounting statement from the collecting offices detailing the transactions and allowing them to be recorded in appropriate ledgers – and then drive the trucks to some shredder/incinerator and destroy the currency notes. So nothing physical survives.

If anyone can point us to any country that has a “shed” (storage depot) where tax revenue is stored after collection and then redistributed as government spending to the non-government sector – that is, the government actually uses the same notes to spend with then I would be interested in knowing about that. It would not alter the MMT view that government spending is not revenue-constrained and would prove only that some governments adopt very quaint habits of denial – as most do by issuing debt to match their net spending $-for-$.

best wishes

bill

Bill – am very happy to have discovered MMT and have read widely on your site, Mosler’s and the Levy Institute: the logic is inescapable. The question of why others can not see this logic is equally as interesting. Just wanted to put the view that the continuous presentation and adaption of the MMT message to current affairs is absolutley vital (Bravo, bravo to all who make the effort !! and please keep on and on …) but the personal attacks are unecessary and probably serve only to consolidate opposition than open up discussion. Am sure you already know that! You only need to hold up a light to chase the darkness out of a room – the character of those in it is self correcting once a truth becomes obvious. Am enjoying your blogs immensely! Music between the lines! Cheers …

Is the objection to using the phrase “printing money” the fact that nowadays most transactions occur electronically, and the printing is only done on demand?

That strikes me as being a bit disingenuous, and I don’t think most people will see it as a meaningful distinction. What is wrong with printing money, anyways? Printed money is much nicer than electronic records and is more secure. What if, in the money center banks, you lost track of a meta-character, and your hundred billion euros turned into a hundred billion swiss francs? I am not at all happy that non-government businesses are supplying software that runs our financial backbone, or that FedWire as a network is plugged into private offices.

Moreover, there is a lot to be said for paper money, particularly as it exhibits something beautiful and useful created by government, Carting boxes of money around will also create employment for those bankers who are not suitable for finding cancer cures. Good, honest work in which they deliver needed funds to the working public at personal risk.

Dear RSJ

No the objection is to the terminology that emerges out of the text books. The government budget constraint literature constructs fiscal policy in such a way that government spending is either tax-financed, debt-financed or “printing money”. They then conclude that the latter is inflationary and so the governnment has to “finance” deficits from debt.

This conceptualisation is clearly wrong – not the least because government spending is always done in the same way – so there are not “three” cases – irrespective of what else the government does operationally (tax collections, debt-issuance). There is no “printing money” option.

That is the reason we disabuse the notion and I don’t think that is disingenuous (even a bit). Unless we educate people to think differently, the tendency is to revert back to the mainstream textbooks which is destructive.

best wishes

bill

ps I have nothing at all against “printed” currency notes. I have a nice aqua 2000 tenge note from Kazakhstan (about $A14) in my wallet at present which is lovely.

Re: printing money . . . also, those using the term almost universally imply this is more inflationary then bond sales, which it is not. And in fact, if anything, the opposite is true, as bond sales add an interest payment to the original deficit.

I see where you are coming from Scott, but imagine this scenario:

Case 1

Me: We should spend more money!

Them: There is too much debt!

Me: We can spend without borrowing!

Them: But that is printing money.

Me: No, it’s not — we add the money electronically.

Case 2:

Me: We should print! Print like the wind! And use the money to create public goods and employ people.

Them: Won’t that cause inflation?

Me: Is there a real risk of wages being too high? Look at the oceans of cars that no one can afford to buy, or the armies of unemployed that have nothing to do, and all the services that are being cut. Wouldn’t it be better if the unemployed could provide those services, they could then afford to buy the cars, and then businesses would make more money and you would have more services. Money is just paper you dangle in front of someone to get them to work. Is the problem that too many people are working or too few?

I have never failed to convince anyone. Then again, I don’t usually talk to economists. 🙂 Even if you were to try to combine case 1 and case 2, I think you would lose credibility and come across as way too pedantic; people are mistrustful of that.

A terrific post, as always.

pb: I hope someone will correct me if I’m off track, but I think one way to see that budget surpluses cannot generate “public saving” in any real sense is as follows. If the government operates a budget surplus when there is unemployment, society foregoes output now that could have been produced with available workers. But not employing these workers in the current period in no way “saves” their labour (and the associated output) for later. It does not increase the amount of labour that these workers can perform in the future. Society could have had these workers producing output both now and in the future. But by opting for “public saving”, the current output is lost and only the future output remains possible.

Dear jrbarch

I agree with you mostly – but sometimes key public players have to be named and brought to account for their writing and advocacy especially when they claim to be objective commentators.

I am not attacking them personally – their characteristics etc – just their ideas and their willingness to misuse their positions of power and authority.

best wishes

bill

Dear RSJ

I don’t think Case 1 and Case 2 are exhaustive. In fact, I think a hybrid Case would have you telling them the plain truth about the operations of the monetary system followed by the second Me: in Case 2.

That is a significantly more powerful option that your (false) dichotomy. So get to it and spread the word – people feel empowered when they really start understanding how it works.

best wishes

bill

Dear Alienated

I think you make a good point about the unrecoverable costs of persistent unemployment – every day’s lost income is gone forever. What a waste.

best wishes

bill

You’re absolutely correct that mainstream economics is brain poison and sovereign governments keep budget accounts by choice rather than by some law of nature. The same issues regarding self-discipline (or lack thereof) apply to government spending whether using a form of enterprise-accounting for income and expenses or dispensing with income accounting and simply accounting for spending. Though it is an “economic” issue only after the fact (when real money changes hands), the decision (choice) to use income-expense accounting (budgets) for sovereign governments is deeply rooted in socio-political realities that will not be diminishing in the foreseeable future. They include (but are not limited to) the following:

1. Fears (which you have seen expressed many times) of “devaluation” of the currency by “flooding” the goods and services market with money credited by the government to bank reserves – relative to the amount of goods and services available (inflation) and/or relative to the amount of foreign currency involved in international trade exchange.

2. Fears of magnifying “wasteful” government spending (a.k.a. “loss of self-restraint”). What is considered “wasteful” and what is not is subjective, of course, and the political process exists specifically to sort values and priorities out (on a democratic basis for the fortunate). The mental analogy held by many is: if a family or business no longer had to have an income source (if, say, a money tree appeared in the back yard), who realistically believes all the”free” money now available would be spent only on necessary or worthwhile things? There is a fundamental distrust of human nature, and it is – obviously incorrectly – believed that governments are “restrained” by using an income-expense budgetary system. The possible incorrectness of this belief is not going to make it disappear.

3. Reluctance to give up the joys of taxation. If you restricted taxation to socio-political objectives (e.g., to discourage alcohol and tobacco use, discourage excessive hydrocarbon use, discourage high-frequency financial speculation), many of the reasons people run for office in the national legislatures would disappear. It’s so crass and obvious to simply write legislation directly giving government money to special interests (though legislators bite their lip and do so rather often), but it is so much more artful and complex to hide the giveaways as tax deductions and credits in a tax code bigger than the Encyclopedia Britannica. That way you get all those donations from the special interests and get a high-paying do-nothing position with the companies you’ve favored after your “public service” is finished, and the voters never really understand.

4. Reluctance to give up the joys of borrowing. If one’s currency is truly sovereign, then (as you have pointed out) one will never default on any loans one makes. By borrowing and issuing bonds – which obligate one to pay an interest rate – one gives financial institutions, other governments, other businesses, and households a way to earn a “risk-free rate of return” which, in turn, becomes an econometric standard against which all other rates of return are measured. All the retirement funds, insurance companies, and even sovereign governments around the world use national bonds (especially the “extra-sovereign” U.S. Treasuries) as their “safest” investment vehicle – a foundation for their portfolios. Currency itself (paper or electronic) does not pay interest, and in the real world for the last hundred years there has always been a positive rate of global inflation except for very limited periods of financial deleveraging.

I could go on. The choice was made three hundred and fifty years ago in capitalist countries to have national budgets, and the vested interests in this system have grown proportional to the size of the governments themselves. New countries joining the capitalist club have added their voices to the triumphalist accolade. Clever governments (like those in the cartoon) have learned to spend as they like and ignore the accounting results when behind closed doors and then deplore budget deficits and make “balanced budget” promises when in public as a form of superficial religious ritual.

P.S. Items #1 and #2 above could be tested in laboratory conditions, as is done with some of the assertions of mainstream economics. Subjects could be put into a closed-economy experiment with the currency made available (by other subjects)according to the model (budgetary or non-budgetary) and the results should give a hint as to whether in fact the rate of inflation is affected by the model and/or spending patterns of the issuers are affected (become more “wasteful”).