I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

A global financial tax?

At present, Australia is embroiled in yet another outbreak of boat people hysteria such that 72 poor souls who took the extraordinary risk to travel across the Indian Ocean to improve their circumstances and perhaps escape political intolerance are cast as being threats to our national sovereignty. The current debate continues years of shameful hysteria which has seen our government imprison children indefinitely because their parents wanted something better. More people come in daily by air and remain illegally than will ever come by boat. Apart from my moral repugnance for the scaremongering, it appears to be hypocritical that the free market lobby always calls for the free flow of capital but rarely for the free flow of people while the left seem to adopt the opposite view. I was thinking about that today when I read that the British PM Gordon Brown has renewed his call for a Tobin Tax. How does that square with modern monetary theory (MMT)? Not very well.

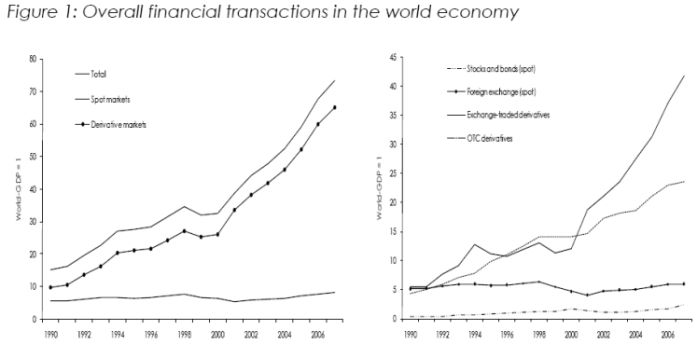

To set things goings consider the following graph which is the reproduced Figure 1 from a recent study from WIFO (Austrian Institute for Economic Research) – A General Financial Transaction Tax: A Short Cut of the Pros, the Cons and a Proposal, which is available in English and is interesting to read.

The graph shows the explosion of global financial flows and derivative markets over spot markets (although the lines are a little hard to distinguish – going back to the original OECD data provides that conclusion).

WIFO describe this dominance as follows:

Observation 1: The volume of financial transactions in the global economy is 73.5 times higher than nominal world GDP, in 1990 this ratio amounted to “only” 15.3. Spot transactions of stocks, bonds and foreign exchange have expanded roughly in tandem with nominal world GDP. Hence, the overall increase in financial trading is exclusively due to the spectacular boom of the derivatives markets …

Observation 2: Futures and options trading on exchanges has expanded much stronger since 2000 than OTC transactions (the latter are the exclusive domain of professionals). In 2007, transaction volume of exchange-traded derivatives was 42.1 times higher than world GDP, the respective ratio of OTC transactions was 23.5% …

In other words, most of the financial flows comprise wealth-shuffling speculation transactions which have nothing to do with the facilitation of trade in real goods and services across national boundaries. This is significant and conditions what my conclusions are later.

Arising out of the G-20 meeting recently, a financial sector tax proposal was mooted. The IMF is considering this idea and said that:

The G-20 officials – representing around 90 percent of the world’s wealth, 80 percent of world trade, and two-thirds of the world’s population – emphasized the need for quick implementation of banking industry reform, saying that stronger standards should be developed by the end of 2010, with the aim of implementation by the end of 2012 as financial conditions improve.

British Prime Minister Gordon Brown said it was time to consider a global financial levy, such as a tax on transactions or an insurance fee, to build up a “resolution fund” as a buffer against future bailouts. Banks needed “a better economic and social contract” that reflected their responsibilities to society. Any measures must be implemented by all major financial centers, Brown noted.

Following the Pittsburgh summit, the IMF has been working on suggestions for such a levy and plans to have some initial ideas by its Spring Meetings in April, to be held in Washington.

The idea of a global financial tax is not new. In the General Theory (1936), Keynes proposed a tax on stock market transactions. Later, James Tobin (1972, then 1978) proposed a tax on foreign exchange and share transactions.

Tobin’s idea is the one people most associate with this sort of tax. He first proposed it during a lecture at Princeton University in 1972 which was subsequently published in J. Tobin (1972) The New Economics: One Decade Older, Princeton University Press, 88-93. It was later developed in his Presidential Address to the Eastern Economic Association in 1978 which was published as J. Tobin (1978) ‘A proposal for international monetary reform’, Eastern Economic Journal, 4.

Gordon Brown has continued to push the idea at a G-20 Finance Ministers’ meeting in Scotland at the weekend. Given they were at St. Andrews I would have recommended they would have used their time better having a round of golf instead of talking.

Brown is quoted as saying that a Tobin tax would provide:

… a better economic and social contract to reflect the global responsibilities of financial institutions to society.

The US does not support the tax, with the US Treasury Secretary being quoted in the above article as saying “A day-by-day financial transaction tax is not something we’re prepared to support”. The French, Germans and other European nations are reportedly in favour of the proposal.

Australia is waiting for the IMF to tell us whether we should have one. Our Treasurer said:

But I just would make this point – that it [the proposal] was raised in the context of countries where there had been massive bail-outs of the banking system. And that has not been the case in our country.

Gordon Brown’s interest seems to be that the tax would:

… make banks pay for the risks the financial sector poses to the broader economy, and the prevailing possibility that the taxpayer will be called upon to the bail them out.

So you immediately see that from a MMT perspective the motivation is suspect. Taxpayers are not bailing anyone out in the current crisis which is not the say that the government isn’t. If the motivation is to “raise revenue” then a MMT would argue this is redundant as the national governments are not revenue-constrained.

The other logical point that I find difficult to agree with is that there is an implicit assumption that bail-outs will occur again so governments better have a bail-out fund.

I would have thought that the merits of the Tobin Tax, which is periodically wheeled out as the solution to financial instability when there is a crisis, but has never been adopted, should be assessed in terms of its capacity to prevent destabilising and damaging financial market behaviour.

If it cannot do that then there is not case for its introduction.

So how does it work?

WIFO proposes that the best option would be for a:

… general and uniform financial transaction tax (FTT). Such a tax would be imposed on transactions of all kinds of financial assets, and, hence, would not be restricted to specific markets …

All foreign transactions would be subject to the ad valorem tax. In his written work Tobin thought rates below 1 per cent would be adequate. Various low rates have been proposed over the years.

It is argued that the Tobin tax is biased against short-run speculative flows. For long-term investment, a small tax would be relatively minor compared to the total scale of the project. But short-term speculators who are moving in and out of a currency sometimes within hours of taking their positions would be more exposed to the tax.

The main aim of the tax is according to a European Parliament working paper would be:

- to reduce exchange-rate volatility by reducing currency speculation;

- to raise revenue for international organisations; and

- to make national economic policies less vulnerable to external shocks.

In terms of reducing exchange-rate volatility, the most effective solution is to impose exchange controls but deposit requirements and/or taxes may also help.

Clearly the neo-liberals oppose any restrictions on the free movement of capital and in certain cases (see below) such movement is beneficial. But given that the overwhelming majority of cross-border financial flows (over 95 per cent) are not related to trade and are rather wealth shuffling, should the world allow them to continue?

Some argue that if a country took unilateral action to stop destabilising speculative flows it would suffer a loss of investment. Tell that to Argentina and Malaysia.

But in general, proponents of the Tobin tax call for a multilateral introduction supervised by the IMF or similar. But it is still possible that destabilising speculative flows can occur given the tax rates proposed are typically very low.

So some argue that the Tobin tax would be a weak or marginal deterrent.

But if it did work, a country which found itself under a speculative threat would not have to contract the domestic economy as much (for example, via interest rate rises or fiscal contractions). Clearly, from a MMT perspective the impact of contracting monetary policy is likely to be less damaging than cutbacks in fiscal policy.

Further, it is argued that the revenue raised could be administered by the IMF to help stabilise exchange rates under attack. Again from a MMT perspective, national governments could all “give” the IMF or a similar institution their currencies to help other nations defend their exchange rates. I examined this notion in this blog – An international currency? Hopefully not!

The mainstream antagonists also argue that it would have be universal or “tax-free” jurisdictions would emerge. They also argue that administratively it would be difficult and there would be major issues defining what the “tax base” was (who is exempt? central banks? etc) and what transactions would be taxable. I have no doubt that some of these issues are likely to be very challenging.

When is speculation reasonable?

It would be wrong to consider all hedging and speculation to be damaging. When it accompanies trade flows and provides security to a trading concern then it can be beneficial. When we talk about hedging in this context we are referring to a strategy to avoid foreign exchange risk (sometimes called covering an open position).

Take the example of an Australian manufacturer which exports into the world market. The firm incurs all their costs in $AUD but contracts, say in $USD and has to deliver in say 3 months time whereupon the foreign purchaser will pay them in USD. Any rise in the AUD against the USD in the meantime will damage the firm’s revenue (in $AUD) but not alter its costs – thus the firm is exposed to losses or profit squeeze. Any fall in the $AUD will benefit the firm when it comes time for the foreign buyer to pay up on the delivery contract.

The firm might “hedge this exposure” in the forward exchange markets by buying a contract to sell $USD at a preferable exchange parity against the $AUD in 3-months time. So say it had worked out that a $USD rate of $AUD1.20 would be profitable then it will seek a 3-month forward contract to sell the contract amount of $USD at that rate.

So in 3-months the firm will get the contract amount (say $USD1000) and sells it to the counter-party at the agreed rate for $AUD (thus, $AUD1200) thereby avoiding all exchange rate exposure.

The same sort of arrangement might benefit an importer who has to deliver foreign exchange at some future date.

Whatever the basis of the contract, a counter-party (the speculator) is required to insure the hedger. While the hedger is willing to pay to cover its foreign exchange risk. the speculator accepts the foreign exchange risk (an open position) and hopes to profit from the contract.

In the case above, if the $AUD appreciates in the 3-month period (say to $AUD1.10) then the speculator who has to deliver $AUD1200 to the manufacturer at $AUD1.20 per USD has to buy $AUD1200 for $USD1091, which means it loses $USD91 less the hedge fee it charges.

If the $AUD depreciates (say to $AUD1.30) then the speculator gains pays $USD923 or the $AUD1200 and gets $USD1000 back, thus making a profit of $USD77 plus its hedging fee.

The important point is that the risk is transferred to the speculator and it is likely that arrangements like this increase the volume of international trade because the trading firm bears none of the risk of the exchange rate exposure involved in the cross-border transactions.

It is more complicated than this but in general this example demonstrates when speculation is beneficial. The common element is when it is helping the facilitate trade in real goods and services which improve material standards of living.

The MMT perspective on a Tobin Tax

It would be futile to deter speculative behaviour that assists international trade in goods and services even though from a MMT perspective the benefits of trade are evaluated differently.

The other question that is begged by the discussions about the Tobin Tax is: why do we want to allow these destabilising financial flows anyway? If they are not facilitating the production and movement of real goods and services what public purpose do they serve?

It is clear they have made a small number of people fabulously wealthy. It is also clear that they have damaged the prospects for disadvantaged workers in many less developed countries.

More obvious to all of us now, when the system comes unstuck through the complexity of these transactions and the impossibility of correctly pricing risk, the real economies across the globe suffer. The consequences have been devastating in terms of lost employment and income and lost wealth.

So I don’t see any public purpose being served by allowing these trades to occur even if the imposition of the Tobin Tax (or something like it) might deter some of the volatility in exchange rates.

Solution: All governments should sign an agreement which would make all financial transactions that cannot be shown to facilitate trade in real good and services illegal. Simple as that. Speculative attacks on a nation’s currency would be judged in the same way as an armed invasion of the country – illegal.

This would smooth out the volatility in currencies and allow fiscal policy to pursue full employment and price stability without the destabilising external sector transactions.

Further, as noted above all the revenue arguments used to justify the Tobin tax are spurious when applied to a modern monetary system.

The proposal to declare wealth-shuffling of the sort targeted by a Tobin tax illegal sits well with the other financial and banking reforms I have discussed in these blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks .

“It would be futile to deter speculative behaviour that assists international trade in goods and services even though from a MMT perspective the benefits of trade are evaluated differently…Solution: All governments should sign an agreement which would make all financial transactions that cannot be shown to facilitate trade in real good and services illegal. Simple as that. Speculative attacks on a nation’s currency would be judged in the same way as an armed invasion of the country – illegal.”

The original argument in favour of speculation in any market is that it is desirable as a source of liquidity where it provides the other side of the trade to a party that seeks to hedge an underlying risk.

There is a similar issue that is discussed sometimes with respect to credit default swaps. Some make the argument that one should not be allowed to buy a credit default swap unless there is an underlying “insurable interest”, which means that there is an underlying exposure to be hedged. E.g. bank X wants to “hedge” its credit risk on a loan to customer Y; so it buys a credit default swap that pays off in the event of Y’s failure. Of course, there is still the problem of why X got into the lending business in the first place, if it wasn’t prepared to assume the credit risk of its customers, as well as the problem of X requiring a counterparty to “write” or “sell” the credit default swap, thereby assuming the credit risk in what could be construed as a net speculative position.

It’s a slippery slope. Exporters and importers would still seem to require speculator counterparties in order to hedge their FX forward risk. Except that international banks provide liquidity to both sides of the market (export and import) by running “forward books” in FX that facilitate hedging by participants in both directions. Inevitability, it is impossible for banks to match up perfectly the positions arising from both sides of the market, so that they end up running limited term structure mismatches in forward FX positions as part of their FX liquidity provision to the trade sector. The ability to run mismatches is essentially to the continuity of the market making function.

The key in all of this is the issue of risk limits for banks and other counterparties that provide a liquidity service to such markets. Any net risk exposure is technically a speculative exposure ex post. It is a question of degree. Identifying the degree again is a slippery slope.

My personal view on all it – this topic and any other connected with the credit crisis – is that the core answer lies in risk measurement, risk limits, and capital requirements. Any speculator can be stopped out from destroying the market by imposing top down regulatory capital requirements in such a manner that makes such net risk taking uneconomic. Such capital requirements would be included for fiends like the US mortgage brokers and investment banks that drove the assembly line of bad securitized housing debt.

Perhaps capital requirements can be construed as analogous to a stock version of a Tobin tax, which in a sense is a sort of flow capital requirement.

The biggest sources of failure in the credit crisis were Basle and the rating agencies. The banks and others were just trying to get away with what they could get away with in a poorly implemented regime of capital requirements.

Tighter spreads have diminishing returns. If spreads are a bit narrower, but you have perennial currency crises, then that is an overall net detriment. Most of the area under the curve in figure 1 is due to a handful of banks, whose prop desks trade against each other. When the eurodollar crisis hit, the Fed provided dollars. That is not something that an ordinary forex speculator can count on, but big banks can. They are in daily contact with treasury, sit on the boards of their regulators, provide a plurality of campaign funding. Knowing that markets are fixed like this creates costs to retail participants that exceed the benefits of tighter spreads.

The issue is not regulations, but power. Looking at it from a systems view, the problem is that you have institutions leveraging their government-backing and ability to get below market funding to drive out/buy up non-bank financial actors in other markets. They then become even more important, getting cheaper access to funding and more government backing (or equivalently, more control over their regulators). At the same time, they serve as both market makers and participants in all of these markets. From short term commercial paper to forex trading to equity trading, a smaller number of players are increasingly accounting for most of the trading volume. We are seeing a crowding out process as part of a growing crisis of legitimacy in the financial markets. Instead of trying to estimate cash flows and investment prospects, investors are forced to engage in a type of Kremlin-watching as they place trades against those in the halls of power. This has profound effects on the ability of credit markets to price risk and allocate capital efficiently. I think this distrust is one of the things holding Japan back, and the detrimental effects of this distrust for the real economy are not appreciated.

The most recent cycle started in 1982 during the Latin American Debt crises, when most of the NY money center banks became insolvent and the regulators looked the other way. When the banks were unable to recapitalize, the government thrashed around with Brady’s proposals to bail them out. Everyone in the country knows that Citigroup has been insolvent for a long time, yet they will not appear on the Friday’s lists. Does it matter what the official capital requirements are? Same thing with the illegal purchase of Travelers — the response was to change the law and repeal glass-steagal after the fact, not to enforce a fairly simple requirement that a big bank publicly flouted.

Why does the FDIC only shut down small banks? Whatever requirements you propose, they will immediately be suspended if the big banks fail to meet them. Regulations will be applied to smaller banks and thrifts, who will then be bought up by the larger banks.

I think at this point, you cannot draw an artificial line between the Basil process and the big banks, as these banks have enormous influence over Basil — it is part of the process by which they create a space for themselves that is off the table for regulators. The same for the ratings agencies. The ability of the banks to create complex instruments and provide mathematical models is impressive. They can outwit the rating agencies and the regulators with 10,000 page financial contracts and off-balance sheet liabilities. Only by forcing them to hold better understood vanilla assets and having very simple liabilities is there hope for regulation or ratings to be effective. Even then, regulators will not have the permission to shut down banks unless the banks become less powerful.

I think the only stable equilibrium is when banks do not participate in any financial market at all. You have to attack the source of power, shrink the banks, and put the banks back into a tight box. Once they escape from the box, they are not going to follow any regulations, but will adjust regulations and laws as they see fit. The solution is not to engage in a regulatory battle of wits, but to diminish their power to escape the box. So I will judge any proposal on the likelihood it has of dramatically shrinking the Finance share of GDP. Unless this number comes down by an order of magnitude, no reform will be meaningful. It will only cause more paperwork for small banks.

Bank assets should consist only of vanilla business and consumer loans and cash in their national currency. We need an iron wall between government-backed lenders and financial markets. Within each private market, we need an iron wall between exchanges, market makers, and investors. A market maker in one market must never be an investor in any market, or hold shares in a bank. No one, including market makers, should be allowed to hold naked positions. I am willing to give up some liquidity and execution speed in order to achieve this.

All governments should sign an agreement which would make all financial transactions that cannot be shown to facilitate trade in real good and services illegal. Simple as that. Speculative attacks on a nation’s currency would be judged in the same way as an armed invasion of the country – illegal.

Does this mean capital controls?

China, for instance, has a system of controls on capital inflows and outflows. Do you agree with such a system?

JKH,

I would also say that in addition to Basel and the rating agencies, Wall Street ideas of risk management was another failure. The models which are supposed to calculate risks are simply ad-hoc and wrong. They are like predicting a flood using the data obtained from drizzles.

My personal opinion is that the rich class has lobbied too much for free markets and all the ideas like that. Change has to come at a fundamental level rather than making some adjustments here and there. And the group of political economists who are actually in power should be trained well on how modern money works because it is absolutely critical – else we may land into the same trouble. This bleeding is a bigger problem – its a failure of the present state of political economy. Refer you to James Galbraith’s book The Predator State

Dear Andrew

I am sorry I haven’t answered this question before (I recall you asking it). The statement you cite from my blog yesterday does not mean that I support capital controls. In general I do not. What the statement means is that I would outlaw a whole class of transactions – anything that cannot be shown to advance public purpose should be outlawed. If all this trouble we are facing is because the Wall Street’s around the world are just betting against each other and duping the rest of us (here I am thinking of the revelations today that Goldman Sachs sold assets that they knew were bad and then without telling anyone – not the least being the people they sold the assets to – they proceeded to short sell them to drive their value down and reap a billions – then put your hand out for government support) – then I would simply outlaw it. Forget trying to regulate it.

best wishes

bill

Ramanan,

Agree on risk management. Risk management rolls up into the way in which capital requirements are formulated, because the purpose of capital is to absorb unexpected losses – i.e. realized risk. Basle followed the yellow brick road of the Wall Street risk models in its formulations. A stronger Basle would have resisted the models.

RSJ has got this essentially correct as far as I can see as I follow developments in the US. Zero Hedge has been documenting this. ZH has only been in existence for ten months and has already received 30 million hits, with 500, 000 regular readers. This is becoming a big deal, and it’s now assumed that the WH and Congress are following ZH as temperatures rise in politics.

This is definitely undermining not only trust in US markets, but also participation as well. The volume of trading in the equity markets recently is all high frequency trading by a few big players that are allegedly frontrunning and pumping the market. With the advent of ZH, this is no longer in the closet, and the Congress is finally getting motivated to act. Charles Schumer of NY is on the case, and he is a very powerful senator that usually can be counted on as supporter of Wall Street.

A big push for a Tobin tax, in the US at least, seems to be coming from those who feel that market makers like Goldman are fleecing them, and that a Tobin tax would at least penalize HFT, since it is unlikely that legislation or regulation can bridle it in an environment where bribery is legal and the government is rented. The thinking is that HFT is extracting a hidden fee on every trade that the government may as well be getting. This is significant because a lot of the people pushing for a Tobin tax are libertarians vehemently opposed to taxation as a matter of principle.

This is no longer simply an economic issue. Things are getting pretty emotional, and it’s becoming a political one. I don’t know that Wall Street can run away from this one.

RSJ,

Strong arguments; I admit not to thinking it all through yet in terms of restructuring the system – just my starting point.