I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Futility, hedging and the Red Cross – its all in a day

Today, I have read a number of different reports from various organisations (IMF, Bank of England, US mortgage brokers, etc.) keeping up to date with what it going on. It all adds up to a bleak way to spend the day although that is the lot I bear (violins out!) as an economist. Imagine being a dentist though (apologies Martin!). Then you would be really working in confined spaces. My confined spaces are the claustrophobic world of mainstream economics. The economic crisis has really demonstrated how stupid (and evil) this body of theory (and policy) is. Anyway, today’s blog reports on what I have been reading and writing about today – all from a modern monetary theory (MMT) perspective – which is the free-range and sunny world that all economists should migrate too!

The futility of it all …

Yesterday, the Bank of England (I wish they would change their orange logo to blue or something) announced their latest policy position. They decided to maintain the overnight “Bank Rate” at 0.5 per cent and increase the size of the asset purchase programme (a.k.a. as quantitative easing) by a further £25 Billion to £200 Billion.

While the rates decision was expected, the so-called “City” (read business fat cats) were critical of the decision according to this Guardian report which carried the headline “Bank of England extends quantitative easing by £25bn – but is it enough?” The business lobby had been wanting the QE to be extended by a further £50 billion over the next 3 months.

I became agitated as soon as I saw the phrase “but is it enough”. It is too much! Too much an exercise in futility, that is.

The BOE’s statement from its Monetary Policy Committee said that:

In the United Kingdom, output has fallen by almost 6% since the start of 2008. Households have reduced their spending substantially and business investment has fallen especially sharply. GDP continued to fall in the third quarter … The medium-term prospects for output and inflation continue to be determined by the balance between two opposing sets of forces. On the one hand, there is a considerable stimulus still working through from the substantial easing in monetary and fiscal policy … On the other hand, the need for banks to continue the process of balance sheet repair is likely to limit the availability of credit. And high levels of debt will weigh on spending.

So they think that a lack of lending and consumers trying to save is impeding growth. I agree. The channel is via aggregate demand which has fallen so badly in the UK that they have experienced 6 quarters of negative GDP growth (its longest slump in recorded history).

The Guardian reported that:

With the government concerned that the lack of credit to business is hindering Britain’s recovery prospects, the chancellor, Alistair Darling, rubber-stamped the Bank’s permission to increase the size of the asset purchase programme.

Here is the Chancellor’s Letter for your interest. What have been the reactions of the other political parties in the UK?

The The Liberal Democrat Treasury spokesman said that:

The Bank of England clearly thinks that the economy is still a long way from recovery. As the UK is one of the last developed nations to still be in recession and with interest rates already at a record low, the Bank has few options other than extending quantitative easing. While the Liberal Democrats support the principle of quantitative easing, it is clear that as banks continue to hoard liquidity, this money is not feeding through to the wider economy. There is now a danger that we are simply throwing more and more money at a problem with little evidence that it is having any positive impact.

Well I wouldn’t vote for him. He is wrong to support the QE policy but right that they are pursuing a policy which will not deliver the impact they desire.

On the Conservative front, I couldn’t find any response from the Tories but they are pushing for a lifting of the ban on hunting, which they consider to be a “brazen” and “contemptuous” and “relentless …. assault on rural England”. I guess that is probably as far as their capacity to conceive of public interest extends.

To kick things off, I liked the following cartoon in the Guardian overnight by cartoonist Steve Bell.

Anyway as background – you might like to read this blog – Quantitative easing 101 – which provides a comprehensive critique of the economics underlying the policy approach.

Quantitative easing merely involves the central bank buying bonds (or other bank assets) in exchange for deposits made by the central bank in the commercial banking system – that is, crediting their reserve accounts. The aim is to create excess reserves which will then be loaned to chase a positive rate of return. So the central bank exchanges non- or low interest-bearing assets (which we might simply think of as reserve balances in the commercial banks) for higher yielding and longer term assets (securities).

So quantitative easing is really just an accounting adjustment in the various accounts to reflect the asset exchange. The commercial banks get a new deposit (central bank funds) and they reduce their holdings of the asset they sell.

Proponents of quantitative easing claim it adds liquidity to a system where lending by commercial banks is seemingly frozen because of a lack of reserves in the banking system overall. It is commonly claimed that it involves “printing money” to ease a “cash-starved” system. That is an unfortunate and misleading representation.

Please never use the term “printing money” in polite company. It is such a loaded and inaccurate term. Government spending (including QE transactions) merely credit bank reserves – via electronic delivery. The Guardian put it this way “The Bank of England … slowed the rate of electronic money growth to boost Britain’s moribund economy to £25bn over the next three months”.

The mainstream economists advocate QE once interest rates get down to zero because they see it as the only stimulatory monetary policy measure left. But their conception of the way the monetary system operates is flawed and also reflects their obsession with the use of monetary policy as a counterstabilising policy tool.

Modern monetary theory (MMT) suggests that monetary policy will not be an effective instrument and QE in particular is a very long bow to draw if your objective is to stimulate economic activity.

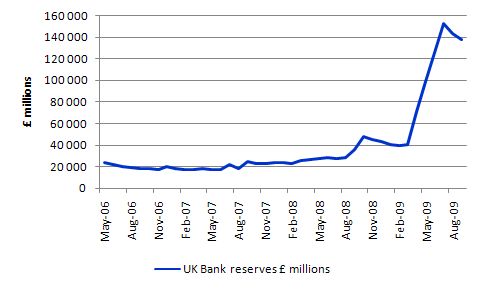

The following graph is taken from the BOE BankStats database and shows monthly UK bank reserves since May 2006. You can see what QE has been doing (along with the expansionary fiscal policy).

Does quantitative easing work? The mainstream belief is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantititative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

This is the text-book conception of the world and parades as the money multiplier theory. It is taught – to their disadvantage – to all undergraduate students in economics. It is an exercise in deceptive brainwashing and those who teach it should be brought to bear.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves. The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

All that the BOE is doing is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the BOE). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, QE increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates.

This might (but probably will not) increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop. But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly. How these opposing effects balance out is unclear. Clearly, the BOE research department has no idea of how the effects interact.

Overall, this uncertainty points to the problems involved in using monetary policy to stimulate (or contract) the economy. It is a blunt policy instrument with ambiguous impacts.

Today’s (November 6, 2009) Guardian Editorial recognises that the policy is “not working”:

… Mervyn King and his colleagues yesterday rightly decided that the quantitative easing would carry on for another three months – but they clearly plan to end this experiment in British monetary policy soon. And the outlook for the economy will get even bleaker.

True, the Bank’s policy has not worked as well as hoped. When he launched QE back in March, Mr King set himself the target of raising the amount of money being circulated outside the banking sector – the point being that he wanted the programme to encourage financial institutions to lend more to businesses and consumers, who would in turn invest and spend more. Yet eight months and £175bn has done nothing to lift that all-important measure – as the Bank now admits …

Mr King is not the only one who plans to withdraw his medicine. So does Alistair Darling, who, come the end of this year, will take back his budget giveaways. If George Osborne moves into No 11 next spring, he has made it clear that he will cut spending sharply and rely on the Bank of England to do the heavy lifting through rate cuts. This is daft. If monetary policy is not having the desired effect and the economy is having a near-death experience next year then the government will have to spend more. Otherwise, the spectre of the great depression is likely to return.

That is it in a nutshell – monetary policy has failed because it was never likely to succeed. The Conservatives are unfit to govern the old dart and fiscal policy has so far not been expansionary enough to fill the spending gap.

The reality is the UK Government has to arrest its tendencies to go along with the deficit hysteria lobby. It has to announce a major stimulus package which will not only directly employ those without work (particularly the youth) but also “finance” the saving desires of the private sector which has to reduce its excessive debt levels. As long as the private sector is trying to restore its precarious balance sheets aggregate demand will falter.

Further, as long as they are trying to save – their will be scant borrowing requests to the banking system. The massive reserves the banks hold are totally irrelevant to their capacity to lend. What they lack are credit worthy customers coming through their front doors seeking loans. That will not happen until there is a resumption of economic growth and that will not happen while private spending is in reverse.

The UK Government should be showing leadership here and expanding their fiscal position. The worst legacy they can leave the future generations is to force them as a consequence of their failure to stimulate income growth now to remain unemployed for the years to come. That is the very possibility that presents itself in the UK at present given that nearly 30 per cent of 16-24 year olds who want to work are jobless.

How did England ever win the Ashes? I suppose they will say that the PM is Scottish.

Using the disadvantaged to hedge …

In a recent blog – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism – I outlined a desirable policy initiative to help home-owners who were facing eviction from their homes because they could no longer service their debts. I suggested the following process which would be within the capacity of a modern monetary government to implement and fund:

- The government should not interfere with repossession processes. A private contract is a private contract.

- But the government should consult with the defaulting private owner to ascertain if they want to keep their house.

- If they do want to keep their homes, the government should purchase the house from the bank that is foreclosing at the fire-sale price.

- The government should then rent the house back to the former owner for some period – say 5 years.

- At the end of this period the former owner would be offered first right of refusal to purchase the house at the current market price.

- The government would also offer the former owner guaranteed employment in a Job Guarantee, to ensure they are able to pay the rent and reconstruct their personal finances.

- This option does not involve any subsidy operating (market rentals paid, repurchase at prevailing market price); no interference into private contracts, and people stay in their homes.

- There is no moral hazard components within the proposal.

Today, I read that Fannie Mae Announces Deed for Lease Program, which effectively means they wil rent to owners who are facing foreclosure.

Under the scheme:

… qualifying homeowners facing foreclosure will be able to remain in their homes by signing a lease in connection with the voluntary transfer of the property deed back to the lender.

Borrowers or tenants interested in a lease must be able to document that the new market rental rate is no more than 31 per cent of their gross income which in most cases will be below their mortgage payments. The leases wil be for 12 months with some month-to-month extensions.

The question that is left hanging is why not make the plan more comprehensive along the lines I outline above?

Further, under “Deed for Lease” program the person has to “demonstrate they can’t afford their current mortgage, but can pay the rent.”

If the US Government supplemented the plan with a Job Guarantee then the ability to pay the rent would be guaranteed. Joblessness and inability to maintain adequate standards of housing usually go together. That is one of the advantages of an employment guarantee approach – the person does not become poor when they lose their job and encounter all the acommpanying costs.

Of-course, you have to question the motive of the Fannie Mae in this instance. The motivation of my scheme is clear and firmly based grounded in the possibilities that a fiat monetary system provides – that is, the scheme is designed to advance public purpose (provide as much chance to the person to keep their house as possible) without compromising the execution of legal contracts between private agents.

But according to the Fannie Mae spokesperson:

This new program helps eliminate some of the uncertainty of foreclosure, keeps families and tenants in their homes during a transitional period, and helps to stabilize neighborhoods and communities.

The same spokesperson was quoted in the Press today as saying:

If you keep more people in their homes, it’s better for the community. It’s better for the financial institutions that own those homes … Hopefully, less foreclosure product on the market will help stabilise those communities.

So you get the feeling that stabilising the community is about stabilising housing values and the 12 month (then month-to-month) lease arrangements ensures that local property markets are not flooded with new stock arising from the defaults. Further, it is highly likely that the same property markets will have picked up over the course of the lease.

So Fannie Mae is attempting to increase the potential value of its stock and push out the former owners onto a rising rental market – with a bad debt against their names.

Further, the occupancy in the meantime militates against urban blight and vandalism which would further increase the value of the housing when it was released onto the market.

In the same breath (released yesterday), Fannie Mae put out its Third Quarter financial results

On page 1 you will read the following:

The loss resulted in a net worth deficit of $15.0 billion as of September 30, 2009, taking into account unrealized gains on available-for-sale securities during the third quarter. As a result, on November 4, 2009, the Acting Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) submitted a request for $15.0 billion from Treasury on the company’s behalf. FHFA has requested that Treasury provide the funds on or prior to December 31, 2009.

In other words, they are wanting the US Federal Treasury to net spend an additional $US15 billion. This is in addition to the $US10.7 billion that was provided to them on September 30, 2009. They also expect further Treasury injections in the future. The total public bailout to Fannie Mae is now standing at around $US61 billion.

So why isn’t the US Treasury insisting on a better deal for the disadvantaged homeowner than Fannie Mae appears to be providing them? Why use the defaulting homeowner as a unpaid “caretaker” to safeguard Fannie’s assets until it is profitable to sell the housing?

And before they even talk about defaults, the US Treasury should just introduce a Job Guarantee and boost the minimum wage to a realistic living baseline. Then allow the homeowners to renegotiate all their financial commitments at the new lower interest rates and see whether the combination of those policy changes allows them to keep servicing their loans.

If so, then the so-called toxic debt becomes “good” debt again and the problem is identified as a lack of aggregate demand leading to a lack of jobs. If the person still cannot pay their mortgage commitments under the revised conditions (JG and lower rates) then my housing emergency plan should be invoked. At some time in the future, I would expect all the “renters” to once again be in a position to re-purchase their houses back at the going price.

A much better outcome for the economy and the people. Fannie’s plan (and Freddie Mac’s similar plan announced earlier in the year) is a cheapskate way to improve their own asset values and the US Treasury should get tough with them.

New Red Cross strategy – punch the victims senseless …

The delusional world of the IMF is never far below the surface. In this extract Debating the IMF with Students the IMF head Dominique Strauss-Kahn was in Turkey in early October and gave an address to some students on the “role of the IMF in the current crisis”.

In his address to the students he:

… likened the IMF to an “economic Red Cross” because its goal is to help solve a country’s economic problems while avoiding social unrest and war … he pointed out that countries only need IMF resources when they are “sick” – when they face serious balance of payments problems requiring policy adjustment. If you go to the doctor with a liver problem, he mused, the doctor will treat you, yes, but will also insist that you stop drinking. So policy conditions are necessary …

But under questioning, he admitted:

… the medicine had sometimes been too bitter in the past. The IMF had developed a “harsh image” – not paying enough attention to local circumstances, political realities, or social consequences. It was seen as more of a policeman than a doctor.

Tomorrow … Saturday Quiz

Regular reader Marshall A. tells me he has scored 100 per cent 5 weeks in a row now. I told him I would fix that. So a particularly tricky quiz is coming tomorrow … only the true MMT crew will get 100 per cent. (Cultural note: Americans – I am joking here!).

hi bill,

as a newcomer to this blog i have been going through your old posts, to glean the many pearls of wisdom.

and a question came to me regarding unemployment.

what would you say to the arguement that part of the neo libereal ideological agenda of the last 30years has been the maintenance of a larger than needed level of unemployment as part of a misguided notion of keeping downward pressure on wage demands.

or am i attributing to a conspiracy where a stuff up would suffice

Excellent post.

I have some friendly weekend kibitzing.

The subsidy is that the government is paying full value for a non-perfoming loan. This is a direct subsidy to banks that hold these loans. That is, unless you want the government to pay “market value” — which isn’t clearly defined and the banks are doing their best to obscure this value. Those loans should be marked down first, sold for a loss by the banks, and have that loss come out of bank equity, with debt-to-equity cramdowns for bank bondholders. Also toss out the top management. Then, go ahead with the program.

For loans on Fannie’s books, the subsidy is to Fannie Mae bondholders and shareholders. Why on earth are they receiving coupon payments when the government is bailing out Fannie? So mandatory debt-to-equity cramdowns, as part of forced receivership for the agencies. Once that happens, Fannie can continue to operate with government infusions of capital if the debt conversion cannot capitalize it adequately.

Moreover, banks are still on the hook if they forward too many non-performing loans to the agencies. They must pay fees in that case, possibly take the loans back on their books if they go sour too soon, and may be barred from doing business with the Agencies. By not enforcing these clawback provisions, subsidies are provided to the bondholders and shareholders of the banks that sold the loans.

The sad thing is that we are talking about lending on (primarily) residential real-estate, not financing speculative venture projects. Really any community college student can do this and not lose money. Just refuse to qualify anyone who doesn’t have 20% down and whose monthly payments would exceed 1/4 of their documented after tax income, charge 10 year treasury + 200 basis points, and hold all loans to term. If Fannie is undercutting you, then get out of the business and make other kinds of loans, or better yet, lobby congress/Fed to regulate banks to prevent this type of competition. Pimpled teenagers may show up late for work, but they wont sink the economy. I’ll take the teenager over Ken Lewis.

All the current top management, their bondholders, and shareholders, should be in a first loss position.. We have FDIC, PBGC, and other safety nets to directly capitalize pension funds and depositors, and keep the actual banks running as their capital structure is changed. We can extend other safety nets to people based on social need, rather than “preserving the existing system” in which financial services and insurance employee compensation consumes 3/4 of net domestic investment.

For borrowers, I like the proposal.

I thought that most heterodox people did not believe in loanable funds; I guess that’s why I keep failing the quizzes. I will try to slay loanable funds:

Financial claims, unlike many tangible assets, can be shorted. This means that the price is not set by the marginal purchaser. Moreover, the actual price of a payment stream must be the consensus view of how much it would cost to create a replacement claim with similar return characteristics. If the risk/duration characteristics cannot be recreated, then you need to add some premium for substitution costs, but nevertheless the compensation demanded when selling the bond is a function of the replacement costs of the income stream, not of the number of claims outstanding per se.

Can retiring claims, in and of itself, change the replacement costs? Certainly if a company is buying back stock, it can change the dividends per share. But a fixed payment risk free government security? You have to argue that the proceeds from the sales, when they are invested elsewhere, will drive down overall returns on capital. The data is not kind to such beliefs, but if there is such an argument or data, I would be interested in seeing it.

Dear RSJ

No, the government should pay the distressed value of the property on the day the borrower approaches the new government agency designed to handle this. It would be the fire sale price. The bank’s shareholders lose as part of the plan would extinguish the liability of the loan. So credit asset, debit loan – bank’s books are clear. The valuation would be independently determined – it isn’t rocket science.

I also agree with all your suggestions to reduce incentives of the banks to “play the system”. Remember also that I would have banks scaled right bank to deposit-taking and loan institutions with all assets remaining on their balance sheets. The proposal to ensure equity is sufficient before the loan is given is good.

On QE: I never said anything that would lead you to think I believed that the loanable funds doctrine is part of the operational reality of our monetary system. It is just a simple matter of taking a lot of paper out of the system and if demand for that paper doesn’t alter then yields rise given the coupons.

I am very sorry you keep failing the tests. The fact you keep doing them is testament to your persistence [:-)]

best wishes

bill

Hi RSJ,

On QE:

Bonds demanded by the private sector depends (in a stock-flow consistent way) on the wealth of the private sector (stock) and also the income (flow). It also depends on the expected returns on the bond. Government deficit increases the wealth of the private sector. The price is the result of a demand-supply equation. Reduce the supply by QE and we have an increase in price. Of course the expected returns and liquidity preferences keep changing. However there is one big factor which is the reduction in supply. So it has to be done on a massive scale to see the effects.

Its easy to confuse this with the crowding out argument. Firstly crowding out argument is not stock-flow consistent. Secondly it ignores the fact that the deficit increases wealth and income. Hence in the crowding out argument, they say that the supply has increased and the demand is the same – a very accounting inconsistent statement because demand also increases in reality.

However you can see that the construction of the treasury market is neoliberal by design as Bill keeps saying.

Excellent presentation. Here in the U.S. the official position of the Federal Reserve is that QE is for the purpose of stimulating lending by banks and excercising some control over interest rates. It is no secret on Wall Street that the real purpose of QE is to make banks appear less-insolvent by exchanging their worthless assets (non-paying CDOs, etc) for valuable Fed reserve deposits. Dollar-for-dollar, there is no net change, but when those worthless assets are sitting on the books of the Fed and the valuable reserves are sitting on the books at the banks, then the remaining worthless assets still sitting on (and off – for the moment) the books at the banks can be “balanced” against liabilities into something resembling solvency. This has always been about the insolvency of the banks, not about lending, which is why the Fed is paying interest (instead of charging it, as would be normal) on excess reserves. All the talk about stimulating lending and “putting a floor under interest rates” is strictly for public consumption.

Ok, I have a question regarding the potential inflationary impact of QE and the bonds/reserves mix that’s been troubling me for some time. It revolves around the fact that reserve creation may or may not be accompanied by bank deposit creation, depending on how the reserves are created.

I understand that it matters little whether a BANK holds government bonds or reserves on it’s balance sheet, except to the extent that interest payments may be due on the bonds and not the reserves. As I understand it, this bank asset swap is what takes place in classical QE, and it makes sense, given the defunct money multiplier theory, that this doesn’t necessarily increase bank lending and hence total bank deposits.

But I’m still struggling with another aspect of the Chartalist position, which (correct me if I’m wrong) suggests that bank deposits in the hands of the public are no more inflationary than government debt in the hands of the public. It seems to me that one can bid up prices much more readily with a spendable bank deposit than one can with a treasury bill, which must be sold to someone else (thus reducing the seller’s bank deposit/spending power) in order to acquire goods/services and hence affect prices.

It seems to me that, when held by the non-bank public, financial assets that are less than 100% liquid must, by their nature, be less inflationary than bank deposits. Or am I still too wrapped up in a ‘quantity theory’ mindset?

Can anyone help me out here?

Hi Bill,

Ahh, this wasn’t clear to me, I agree.

The loanable funds is the view that yields are the result of a supply-demand relationship between funds available for investment and investment opportunities.

In reality, businesses can sell claims into the market. Investors can sell existing assets and use the proceeds to buy these claims. The price the claims fetch is the cash available for the business to invest, but what really “funds” lending or investment is the assessment of future returns rather than cash, as cash is not “used up” when an investment is funded, but is immediately available to fund other investments. Cash is just the measuring stick against which balance sheets are judged.

The result of issuing more claims is an expansion of the balance sheet of the business. In the same way, a borrower “sells” his earning power to a bank, who qualifies him for a loan administratively rather than as part of a market process, but this also causes a balance sheet expansion of the borrower. A similar event can occur within a company, if you’ve ever pitched a project to management. It’s not easy 🙂

Barring a breakdown in settlements (e.g. a real liquidity crisis, which is rare), there is never any shortage of cash, and the only cash you need is enough cash to keep all the pricing operations humming as balance sheets continually expand and contract due to shifting expectations.

Therefore the market assessment of investment opportunities determines the level of investment funds.

There is never any demand for bonds. There is only demand for yield, or a payment stream. To paraphrase Marx’s rebuttal of Say’s law, “Investors never demand bonds for their money, but money for their money.” 🙂

When I sell my holdings of treasuries for cash, I am already doing a calculation in which I estimate my returns in investments other than treasuries. I demand enough cash so that I can purchase another investment in this smaller universe and maintain my risk-adjusted return. If I did not do this, I would not sell my treasury holdings. Every investor does this as the market gropes towards indifference between the cash price of equities and bonds of all sorts.

Markets are never perfectly liquid, but to the degree that they are, indifference between claims is achieved. As long as interventions are the result of voluntary transactions at market prices, the act of substituting one claim for another will not affect yields except by a small spread — whatever premium is required to nudge indifferent investors one way or another. Once the intervention ends, that spread will go away. Obviously the situation is different if the government were to buy up all the assets — then yields would not fall, they would be undefined. If the government bought up all but a little bit, then it’s hard to say what would happen. Maybe a lot of inflation as the U.S. has over 100 Trillion in assets — but as long as intervention is done in an orderly way and limited way, the non-government sector has plenty of liquid assets to buy that can be expected to yield in aggregate the nominal GDP growth rate. Fixed payment assets will only be bought if the discount from this expected yield is not too steep, given the risk-bearing capacity of the private sector, which of course is volatile.

In regards to excess bank reserves, why not get rid of them all together? The problem is that the desire to lend ebbs and flows, and if the government supplies reserves on demand, it needs a way of reducing reserves when demand decreases. It should not pay banks just for having money, particularly as the government is the source of the money. Money should always be a cost to banks, but free to the government.

Suppose that banks cannot loan more than the minimum of (kDeposits, LBankCapital), where K and L are constants, and Bank Capital is only cash kept with the central bank as a pledge to cover loan losses. All loans are funded by government money, on which the bank pays interest. Such a system has no excess reserves, only possibly excess bank capital, which can be returned to investors to deploy elsewhere.

I still maintain that even though the government can control a bank’s cost of funds, the government cannot control short term non-bank rates such as the 3 month rate — other than deposit rates. This is the case barring unhealthy situations such as banks getting low cost funds from the government and using the proceeds to buy up financial assets. But I will keep taking the quizzes and getting those questions wrong 🙂

Hallo Ramanan,

Long time-no debate!

Happy November!

The idea of demand curves falling with quantity does not apply to prediction markets. People may get into bidding wars for apples but they do not get into bidding wars for money.

If you believe a CDO is worth 10 cents, you will not pay 20 cents for it, whether there are 1 million CDOs or 100 million CDOs available for sale. Moreover, if the market price is currently 30 cents, you will short the CDO and use the proceeds to buy some other security that gives a better cash-flow.

The possibility of arbitrage for liquid securities means that they end up priced in such a way as to approach indifference, which means that the expected return at a given time horizon is the same for all instruments. Therefore changing the composition of private sector balance sheets does not change expected returns. Of course there is a big difference between the expected and actual returns.

So what “funds” investment? The exact same thing that funds loans. Expectations of future profits.

Suppose Verizon wants to raise funds by selling 10 year bonds. They need to convince someone who already holds a liquid asset to invest, and then that investor trades his asset for the Verizon bond. If, by the indifference principle, the asset that person held had an expected return of X over the next 10 years, then the expected return of the Verizon bond also has to be X. Note that that the expected return is not necessarily the quoted yield.

If the investor was correct in assessing Verizon’s ability to pay, he managed to fund business expansion without parting with anything. Imagine, before workers were not working, and now they are working, and no cash was used up in this process.

The investment funds itself, provided that it is expected to earn a return equal to the return that all other investments are currently earning.

Also note that the business could have funded the investment out of retained earnings. So the business will only issue bonds if the bond yield is less than the cost of equity capital. On the other hand, the investor could have bought Verizon stock instead of debt, in which case the bond yield has to be greater than Verizon’s cost of equity capital. This forces the quoted bond yields to be some discount over equity returns that reflects the estimated likelihood of the equity returns not being realized during the bond period.

When expectations are positive, balance sheets swell across the board as business investment occurs, and when they are negative, those balance sheets shrink as assets are marked down. This puzzles those who believe in loanable funds type theories since they assume that there must be a shortage of money, and that therefore if they added more money, then more investment would occur.

But unlike running deficits or surpluses, monetary policy does not change the financial position of the private sector. As long as there is enough cash for settlements to proceed smoothly, reducing the amount of cash and replacing it with another liquid security makes no difference, as that security was already priced at its cash value before you made the exchange.

The responsibility of government here is to ensure that the settlement infrastructure is such that all traded securities remain liquid, that is they can quickly be converted to cash and quickly purchased with cash at the last quoted price. Part of this may require adding cash as the economy grows, but a robust fiscal policy should take care of this without requiring monetary policy.

So there is no reason for monetary policy at all except for keeping bank funding costs in line with the cost of capital of the non-bank sector. If you do not do this, then banks will buy up financial assets and earn a risk-free return from the spread — effectively using their government backstop to incur more risk than those without a backstop are willing to incur if they had to bear the risk fully with their own capital. This is always the problem with banks, and why all banks fail. But there are other ways of mitigating this — e.g. robust reserve requirements, levying other taxes or fees on banks, and/or preventing banks from holding any financial assets other than loans. If you could get around this problem in a satisfactory way, then there is no reason to engage in monetary policy at all.

I claim that if you do this, then you will discover that interest rates are indeed endogenous, and simply reflect expectations of future nominal growth rates for each time horizon.

Hi RSJ,

Yes long time no debate. Again so many things from your side!

In economics/finance one can’t do a controlled experiment so argument is your best friend. I like the liquidity preferences argument a lot. e.g., in the case of bond auctions, if the 10y yield for the US is 3%, x bonds might be sold, for 4% y bonds and so on. The yield of the bond is then the price in which the Treasury manages to sell all bonds. The important thing here is that lot of things are changing. Wealth of the private sector, income etc and one needs to look at this in a stock flow consistent manner. Else one would reach conclusions such as crowding out.

CDOs are different because they are derivatives and their prices depend strongly on the underlying.

In your example on Verizon bonds, there is an important thing. For bonds, analysts, traders and fund managers look at whether the company will be able to pay off its debt rather than how well it is going to grow. Here too liqudity preferences matter. Simply because Verizon is yielding 6% and Treasuries are yielding 4% doesnt mean one is better than the other. There are many investors and some would prefer the former and other the latter. Some would prefer a mix. Liquidity preferences are a good way of describing because the economy is made up of all sorts of things and if you just concentrate on the return, you might end up concluding that people stop consuming and put all their money in the market.