I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When all you do is distribute rather than create

The weekend’s Sydney Morning Herald carried a syndicated article from the UK Telegraph – Why the economy needs to stress creation over distribution – which bears on the recent discussion about financial market profits and executive packages. If we were to follow this remuneration pattern then things would be very different in the world. Probably for the better. It also shows how the explanations for earnings provided by mainstream economics textbooks are ridiculous in the extreme. Another reason to stay clear of those courses at University.

The article by Roger Bootle proposed that:

The whole of economic life is a mixture of creative and distributive activities. Some of what we “earn” derives from what is created out of nothing and adds to the total available for all to enjoy. But some of it merely takes what would otherwise be available to others and therefore comes at their expense. Successful societies maximise the creative and minimise the distributive. Societies where everyone can achieve gains only at the expense of others are by definition impoverished. They are also usually intensely violent.

Bootle thinks doctors and nurses are 100 per cent creative in their work although teachers are “further along the spectrum towards distributive gains”.

I thought about that for a moment having spent my professional life as an academic allegedly nurturing the next generation of minds. It has actually been one of the personal conflicts I have had with my career. The reality is that in most capitalist nations, education has not become an inalienable right and retains a strong privilege component that the rich can access in greater measure.

Even primary and secondary schooling is distributional in the sense that the better schools funded by richer parents provide higher amenities than the state schools which have become progressively under-resourced as the neo-liberal onslaught gained momentum.

And the privilege angle gets worse as you get into higher education (where I have hung out) because by then access alone is highly biased towards to the children of high income families. Even though the Australian government (Whitlam) reduced the costs involved this was ineffective. In fact, despite what the standard left-leaning person thinks, this policy was one of the largest redistributions of income from the poor to the rich. It gave wealthy familes thousands of dollars extra (by not having to pay the fees) and did little to improve participation at the other end of the income scale (because the kids had already left secondary school).

So being a teacher is to be part of the system that perpetuates income inequality and reinforces the capitalist work ethic. The segmented market literature considers education (particularly at university level) to be as much (or more) a process of preparing people for the capitalist work place – learning servility and authority (no student tells a professor they are talking nonsense); learning to be bored in return for better marks (later to be replaced by boring work for pay and promotion); etc. as it is a productivity-augmenting process (as mainstream human capital theory constructs it – more about which later).

It gets worse when you consider the pressure the corporate sector places on the educational system to allow it to influence the curriculum. There is now a higher vocational element in business degrees (just the concept of a business degree!) than there ever was in the standard commerce degrees of the past.

And … the bullying way in which mainstream economics is taught in universities exemplifies the distributional element of the process. Students are not encouraged to think. They are forced to rote-learn from textbooks that have little relevance to anything remotely like the real world that we live in. They are a stylised confection of a system that the economics profession would like us to live like and they are insensitive (hostile) to anyone who questions it. The only creativity in being an economist, in my view, is surviving the formal educational hurdles (exams, postgrad, getting published, getting research income) if you are not of the mainstream persuasion. I have first-hand experience of that creative process.

If you are interested in the sociology of education from a non-coventional perspective then you might like to read Schooling in Capitalist America which was published in 1976. It is a little dated now and very US-centric but the general principles outlined are worth considering.

They argue that schools are structured to correspond to the way workplaces are organised (hierarchies, codes of conduct, discipline systems etc). As a consequence, children are being “educated” into how to behave in the workplace. Further, education becomes a control mechanism where the capitalist power elite develop control mechanisms to maintain their position at the top. Schooling encourages an acceptance of inequality of outcomes and builds the image that these outcomes are merit-based and therefore justifiable.

Anyway, that little digression made me feel better.

Bootle continues to pigeon-hole different occupations into creative and distributive activities. He then considers the:

… marketing executive for a washing powder manufacturer. Her job is pretty much purely distributive. It is to do her best to ensure her company sells more washing powder than its rivals. If she succeeds, the rewards will be greater for her and her company. But her success will be mirrored by other companies doing badly. Her contribution is purely distributive.

Okay, we now know the logic. But what about financial markets? I have written before that my friend Warren Mosler (who has spent a lifetime in the “markets” as a big player) has a saying “The financial sector is a lot more trouble than it’s worth”, which implies that financial markets are very distributive and not very productive (creative).

Bootle, himself asks “But do the financial markets do too much of the distributive?” This is in the context of the huge pay cheques the banking industry provides to their executives under the cover of the “they are creating wealth”. He says:

They argue we should praise, even ape, such people rather than criticise them, thereby concentrating on the distribution rather than the creation of wealth. This misses the point. We should not be mesmerised by the millions of pounds squirrelled away. The question is, what has the process that generated this money contributed to the common weal?

The reality (and Bootle agrees) is that most of the day-to-day activity in financial markets is not about directing funds to productive investment – that is, building factories, developing new processes, funding research and development etc. Most of the activity is about what I call nominal wealth shuffling – or in less abstract language – common to all – gambling.

You construct a bet – find a counterparty to bet with – place the bet – take the gain or loss. Outcome for society – nil. Outcome for players – one wins, the other loses. It is a bit more complicated than that but not much more so.

It has always amazed me how we extol the virtues of the so-called “wealth creators” (the hedge fund magnates and the big bankers etc) yet we look askance at low-income workers who gamble their meagre family incomes away in their obsessions with a few horses running around a track.

This duality in the way we construct events extends to other aspects of life. A hopeless alcoholic lying in the street is reviled by mainstream society yet the wealthy drunken lawyer or banker at the “dinner party” with his hands all over the women (they are usually men) is seen as the epitome of success and just letting off a bit of steam. Of-course, both end up spewing in some corner of their respecitive worlds after their alcohol excess.

Bootle confirms this perception of the financial markets:

Much of what goes on in financial markets belongs at the distributive end. The gains to one party reflect the losses to another, and the fees and charges racked up are paid by Joe Public, since even if he is not directly involved in the deals, he is indirectly through costs and charges for goods and services. The genius of the great speculative investors is to see what others do not, or to see it earlier. This is a skill. But so is the ability to stand on tip toe, balancing on one leg, while holding a pot of tea above your head, without spillage. But I am not convinced of the social worth of such a skill.

Government policy over the neo-liberal period has helped provide the capacity for non-productive workers (like much of the banking industry) to make greater claims on real goods and services.

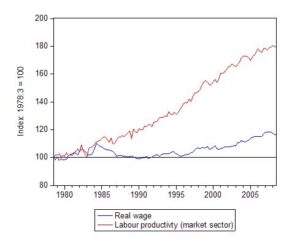

I have produced this graph before but it is worth remembering. It shows the evolution of real wages and GDP per hour worked (in the market sector), that is, labour productivity for Australia since the early 1980s (as the neo-liberal onslaught began in earnest). Similar graphs can be generated for most nations around the Globe. In Australia, real wages fell under the Hawke Accord era which was a stunt to redistribute national income back to profits in the vein hope that the private sector would increase investment. It was based on flawed logic at the time and by its centralised nature only reinforced the bargaining position of firms by effectively undermining the traditional trade union movement skills – those practised by shop stewards at the coalface.

Under the conservative Howard years, some modest growth in real wages occurred overall but nothing like that which would have justified by the growth in productivity. In March 1996, the real wage index was 101.5 while the labour productivity index was 139.0 (Index = 100 at Sept-1978). By September 2008, the real wage index had climbed to 116.7 (that is, around 15 per cent growth in just over 12 years) but the labour productivity index was 179.1

What happened to the gap between labour productivity and real wages? The gap represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital. The Federal government (aided and abetted by the state governments) helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation; the National Competition Policy to name just a few of the ways.

In part, it was this policy-confected divergence between real wages and labour productivity that diverted more real output away from workers. This gap provided the access to the top-end-of-town to pay themselves grand salaries and bonuses and convert the nominal gains into hard assets – big homes, boats, parties, clothes, buying sporting teams, and the rest of it. You can read more on this here.

And it is this link with the real economy which is the problem. If the distributive element of the financial markets – the nominal wealth shuffling – was confined to their domain then we might be less concerned. The problem is that the real economy – where output and employment is generated – is not insulated as we have seen over the last few years.

Bootle says of this:

Perhaps the greatest problems are caused by the interaction between financial markets and the real economy. There time horizons are longer, price adjustments more sluggish, and motivations less single-mindedly selfish. And so much the better – for them and for us. But how can they withstand the rush of supercharged greed from the financial markets? If we think it is right – and economically advantageous – that some parts of the economy should not be organised like investment banks, we should make sure they are protected from those parts of the system that are organised like investment banks.

That is the major issue. The way to withstand it is to reform the financial sector. You might like to read some preliminary comments on this which appear in these blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks. We are working on a more elaborate version of these thoughts to consolidate them into a fully integrated policy platform.

But the ability of the financial markets to cause havoc would be lessened dramatically if:

- banks were only be permitted to lend directly to borrowers and all loans would have to be shown and kept on their balance sheets. All third-party commission deals which involve banks acting as “brokers” and on-selling loans or other financial assets for profit would be banned.

- banks were prevented from accepting any financial asset as collateral to support loans. Credit risk would be assessed more accurately as a result.

- banks were prevented from having “off-balance sheet” assets, such as finance company arms which can evade regulation.

- banks were not allowed to trade in credit default insurance.

- banks were restricted to the facilitation of loans and not engage in any other commercial activity.

- banks were prevented from contracting in foreign interest rates.

If you supplement these restrictions with the central bank and treasury reforms outlined here then substantial benefits would be forthcoming.

Further, if the system prevented the divergence between real wages and labour productivity from occuring there would be less need for households to acquire debt to maintain spending growth and less real goods and services available for the purely distributive areas of our economy to ultimately get their hands on.

Now, what would you learn about this if you were to study mainstream economics at a university? As I noted recently, a popular textbook used by university lecturers is some version of Mankiw’s Principle of Economics. My quotes are from the first edition published in 1997 but it is representative of the twaddle that mainstream economists parade as knowledge.

Mankiw’s Chapter 19 covers earnings and discrimination after Chapter 18 covers marginal productivity theory.

What causes earnings to vary so much from person to person? … the basic neoclassical theory of the labor market, offers an answer to this question … wages are governed by labor supply and labor demand. Labor demand, in turn, reflects the marginal productivity of labor. In equilibrium, each worker is paid the value of his or her marginal contribution to the economy’s production of goods and services.

I plan to write a critique of marginal productivity theory in a future blog. You might like to review this Chapter for a fairly standard crtique.

The bottom line is that the theory was shot to pieces during the famous Cambridge Capital Controversies and could not possibly be a true rendition of what happens.

At the aggregate level, labour demand is a function of aggregate spending and the concept of marginal productivity is undefined in any meaningful way. Trying to add up individual firms using marginal product-derived demand functions to get an aggregate labour demand function is impossible. But this flawed conception still underpins everything students are taught about income distribution and the personal distribution of income.

Mankiw then continues to rehearse the standard neo-classical causes of wage differentials. Yes, they recognise that even in a competitive labour market with no government regulations there will be wage inequality. But there is an optimal reason for it.

First, there is the theory compensating differentials which says that wages are “only on of many job attributes that the worker takes into account … the better the job as gauged by these nonmonetary characteristics, the more people there are who are willing to do the job at any given wage.” Which means that the wage should be lower for cleaner, safer, more interesting, higher status jobs. The evidence is of-course not evenly remotely like this.

Second, human capital – the more of it the higher wage because you are alleged to be more productive. So the longer you stay at school (up to the point of diminishing returns – read, doctorates) the higher your pay will be. Segmented labour market theorists acknowledge the observational equivalence (length of schooling and higher wage outcomes) but argue that education is less about productivity-augmentation and more about screening (along the lines discussed above).

Third, natural ability – top golfers get more than lower grade golfers. Fourth, effort – “some people work hard, others are lazy” – that is, they are more productive. But then a manual labourer should earn stacks. Fifth, chance plays a part – you learn a skill that becomes obsolete – bad luck.

Put together these models explain very little other than to draw correlations. Most of the variables are unmeasurable.

The mainstream economic models used to explain earnings become very complicated. The typical pattern – no substance yet blinding complexity. I dug this recent article up – no link will be provided to ensure they don’t think it is popular – to give you a feel for how the mainstream would justify the Wall Street binge-remuneration.

Here is a typical opening sentence aimed at characterising the workers or the labour supply in the “model”:

When you have stopped laughing then consider this. Here is the way the authors construct the bosses on the demand side of the labour market they are claiming is telling us something about the way wage determination works in the real world:

So knowledge content zero. Students parrot this nonsense relentlessly back to their examiners and get the credential they were seeking. They then go into the workforce fully trained in tolerating arrant boredom for the carrots the bosses provide them.

It is clear that mainstream economics has nothing to say about the way the labour market distributes its rewards. To understand why Goldman Sachs pays so much you need to get your hands dirty in the world of power relations, distributional politics and the rest of it. These excesses have accompanied major shifts in government behaviour towards an anti-union, pro-deregulation stance. That change has significantly increased the capacity of the top-end-of-town to successfully make deplorable claims on the distribution system.

A backlash is required … spread the word.

In terms of my current Goldman Sachs mini-series, I thought this article – Goldman Sachs Is Robbing Us Blind – was noteworthy.

The author Dylan Ratigan is part of the mainstream media which means that the sentiment that something is wrong is spreading even if the understanding of what it wrong is not.

He said:

In a world where real competition, modern technology and lack of special government standing means most American businesses have no choice but to adapt and innovate — Wall Streets wimps only apparent skill is rigging the game.

In fact, on Wall Street there have always been only two basic ways to make money. The first and most difficult: Be a great investor — to the best investors go the profits, rewarding those who are best at picking winning businesses for America and punishing those who fail through the loss of their money. The second, and seemingly preferred method, exploit those who know less than you — and take their money, even if you have to change the laws to do so.

He argues that conventional investment in shares and bonds “became a very low margin business because of modern information” (Internet in particular) but the “the legalization in 2000 of a secretive market for crooked insurance with no transparency or accountability has been an absolute boon”.

In analysing the rise of credit derivatives over the last decade he says that banks became insurers and to make money they:

… exploit two loopholes. The first — overcharge customers by depriving them of the type of competitive pricing only possible on an exchange like the New York Stock Exchange or Chicago Mercantile Exchange. And the second, exploit the lack of transparency to hide the fact that you are keeping little or no money to pay claims while selling insurance and collecting fees on every house and pension payment in America.

Then the punch-line – don’t pay up when “when there is a default or claim against that so-called credit insurance” – just seek government support to avoid collapse. Ratigan concludes that this “quite simply, is a brilliant way to steal our money”.

The theft is perpetrated because governments allow the derivatives to continue and also do not force banks to hold cash in reserves in case of defaults.

At the same time, JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs are enjoying huge profits and paying out huge bonuses.

Ratigan says:

Considering the $23.7 trillion of taxpayer money being used to support these Corporate Communists one would hope they could at least make a few billion in profits with it. In context, making a few billion risking a few trillion is a rather pathetic return after all.

Clearly his indignance is because he thinks it is “taxpayer money”. But an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) tells you that taxpayers do not fund anything because the national government is not revenue constrained. But upon understanding that the level of indignances should remain because the public spending could be better used to advance public purpose. Like educate a child from a disadvantaged neighbourhood or discover a cure for HIV-Aids (to help the developing countries) or cancer (to help us all).

I also like this new extension of the term corporate welfare – to corporate communism. At the height of the “reds under the beds” years in Australia’s post Second World War purge on communists (we just aped the McCarthy pogroms), the biggest supporter of state socialism was the rural arm of the conservative party in power (the then Country Party). They had their private hands out whenever a government official was in sight.

Ratigan also hints at needing more creative and less distributional workers in Wall Street. He says:

What we want, is a Wall Street that would attract men and women who would seek to be the next Warren Buffett, or great venture capitalist. Men and women competing to analyze the countless ideas of our best and brightest – investing in those who will best be able to bring their innovations to America and the world

Conclusion

So even the relatively conservative financial press are starting to react to the indecency of what is happening at present.

It will only change if us citizens empower ourselves and fight back. As I noted recently, the Internet is a great domain to organise struggles like this.

Administrative note – the next week or so

From later this afternoon (Monday) I am on my way to Kazakhstan to meet with officials from the various Central Asian governments. I will be back in Newcastle next Tuesday. I am a bit unsure of what sort of connectivity I will have while away and so if the blog frequency falls you will know the reason.

The mission is part of a 3-year Asian Development Bank project that I am working on and relates to the provision of macroeconomic risk asssessment and advice to several Central Asian governments, the design of regional development strategies where public sector job creation and integrated skills development becomes the centrepiece and a strategy de-emphasising privatisation, deregulation and export-led (IMF) style development.

I am working on a new book with a colleague which will outline a new strategy for economic development in developing countries that is grounded in modern monetary theory and our practical experiences of working in these countries. It will hopefully be out in the first half of next year and will challenge the current orthodoxy which has just made the developing world poorer.

I imagine I will have excellent connectivity in Almaty and Dubai and so continuity will not be a problem. But for commenters – I am bit behind in my replies and will get to that in the coming week. Also if your comment does not appear for some time it is because I am flying and I will make them active as soon as I can. I have to moderate them to stop the spammers.

The idea of distributive vs creative.

I dont think I would be the only one who is very unesy about the Australian economy in 2016.

All we are doing is building dwellings for each other. Building houses and units creates short time jobs. When the house is finished the jobs are gone. Then what?

Can a whole nation exist on say 90% distributive?

We may find out soon enough.