The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Commercial banks make higher profits when interest rates rise

I operate on the basis of first seeking to understand the phenomena I am addressing through logic and recourse to the evidence base. I am very cautious in my public statements – oral or written – and always seek to consult the knowledge base. I noticed a comment in response to yesterday’s blog post – The RBA has lost the plot – monetary policy is now incomprehensible in Australia (July 6, 2022) – that insinuated that I was writing nonsense in relation to my claim that commercial banks enjoy higher interest rate environments because they can make more profit. Anyone is welcome to their opinion, but not all are of equal privilege when it comes to these issues. If you understand the basis of commercial banking and the vast amount of research on the proposition you will have no doubt in concluding that commercial banks do not like it when interest rates are low and will make more profit now that the RBA is hiking rates. To opine otherwise tells me that there is a lack of understanding about the basis of commercial banking and a disregard (perhaps ignorance) of the research literature on the topic.

What do banks do?

The evidence is clear that commercial banks are more profitable when interest rates are higher.

You might be tempted to conclude that this is because debtors pay more interest on their outstanding loans.

That conclusion is too superficial because it doesn’t really capture the basis of commercial banking which is to exploit interest rate spread in order to make profits.

The profit margin of a bank is crudely the difference between what it can get from making loans relative to the cost of acquiring the funds necessary to make those loans.

As an aside, one might be a little confused because doesn’t Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) say that loans create deposits, which suggests that banks just type numbers in relevant bank accounts and the deposits are created.

The ‘loans create deposits’ reality is in stark contradiction to the erroneous mainstream view that deposits are necessary prior to the bank making the loans and that banks loan out reserves.

If that is the case, why am I then talking here about the ‘cost of acquiring the funds necessary to make these loans’?

I discussed that issue in this blog post –

The role of bank deposits in Modern Monetary Theory (May 26, 2011).

Banks do function to take deposits, which provide them with the funds that they can then on-lend.

They certainly seek to maximise return to their shareholders. In pursuing that charter, they seek to attract credit-worthy customers to which they can loan funds to and thereby make profit.

Banks do not loan out their reserves to their customers!

The commercial banks are required to keep reserve accounts at the central bank.

These reserves are liabilities of the central bank and function to ensure the payments (or settlements) system functions smoothly.

That system relates to the millions of transactions that occur daily between banks as cheques are tendered by citizens and firms and more.

Without a coherent system of centrally-held reserves, banks could easily find themselves unable to fund another bank’s demands relating to cheques drawn on customer accounts for example.

Banks thus will have a reserve management area within their organisations to monitor on a daily basis their status and to seek ways to minimise the costs of maintaining the reserves that are necessary to ensure a smooth payments system.

When a bank originates a loan to a firm or a household it is not lending reserves.

Loans create deposits but the reserve balances have nothing to do with this – they are part of the banking system that ensure financial stability.

These loans are made independent of their reserve positions.

The reserve management division within a commercial bank is functionally separate from the loan division.

The commercial banks will seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period.

There are multiple sources (interbank market, central bank discount window, wholesale funding markets, and deposits) and bank deposits are one way the bank can cover its payments obligations.

When a bank makes a loan it creates a bank liability which can be used by the borrower to fund spending. When spending occurs (say a cheque is written for a new car), then the adjustment appears in the reserve account the the bank that the cheque is drawn on holds with the central bank.

Does the bank’s reserve fall as a consequence? Not necessarily because it depends on other transactions.

What happens if the car dealer also banks with Bank A (the consumer’s bank)?

Then Bank A just runs a contra accounting adjustment (debit the borrower’s loan account; credit the car dealer’s cash account) and the reserve balance doesn’t change even though a settlement has taken place.

There are more complicated situations where the reserve balance of Bank A is not implicated. These relate to private wholesale payments systems which come to the settlements system (aka the “clearing house”) at the end of the day and determine a “net position” for each bank. If Bank A has more cheques overall written for it than against it then its net reserve position will be in surplus.

What does that all mean? Loans are not funded by reserves balances nor are deposits required to add to reserves before a bank can lend. This does not deny that banks still require funds in order to operate. They still need to ensure they have reserves. It just means that they do not need reserves before they lend.

Private banks still need to ‘fund’ their loan book. Banks have various sources of funds available to them, which vary in ‘cost’.

The bank is clearly trying to get access to funds which are cheaper than the rate they charge for their loans – that is maximise the spread.

So they will go to the cheapest funding source first and then tap into more expensive funding sources as the need arises. They always know that they can borrow shortfalls from the central bank at the discount window if worse comes to worse.

So the profitability of the loan desk is influenced by what they can lend at relative to the costs of the funds they ultimately have to get to satisfy settlement.

In other words, the price that the bank has to pay for deposits (one source of such funds) impact on the profitability of its lending decisions.

Domestically-sourced deposits are usually cheaper seeking funds on money markets and/or the central bank.

I will come back to that.

Just yesterday (July 6, 2022), the RBA released its latest banking indicators – The Australian Economy and Financial Markets – which help us understand this question more deeply.

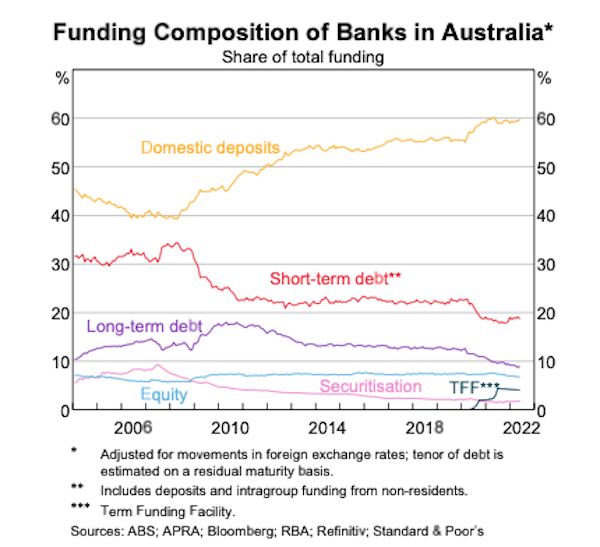

Within that Chart Pack, they produce a number of Banking Indicators (starting page 30), which include the ‘Major Banks’ Net Interest Margin’ (p.30) and the ‘Funding Composition of Banks in Australia’ (p.31).

Here is the graph that tells us that Australian banks rely mostly on bank deposits to ‘fund’ their loan books.

It is clear that the commercial banks have increasingly relied on domestic deposits for their funding.

So when we talk about commercial banks managing spread we are really focusing on the difference between mortgate rates and the customer deposit rates.

The mortgate rates move, more or less, in line with the RBA’s cash rate target.

The linkages are that a rise in the cash rate target increases the borrowing cost in the interbank market (the overnight market where funds are shunted between banks to manage reserves).

The overnight rate is the foundation rate for other short-term lending rates in the money market.

Why?

Simply because if the bank can gain a higher yield safely by lending in the overnight market it will require higher rates for making loans that extend in time.

As short-term rates rise, they feed into the longer investment rates, including home mortgage rates.

When mortgage rates rise, the banks obviously enjoy higher nominal interest income flows.

But that is only one part of the story.

Given the dependence of the commercial banks on deposits, the capacity to gain higher profit margins as mortgage rates rise depends on the trajectory of deposit rates.

There are clearly a range of deposit rates depending on the fixity of the deposit. Longer term deposits attract higher returns than deposit accounts that allow instant withdrawal without penalty.

Most deposit accounts pay zero or negligible returns.

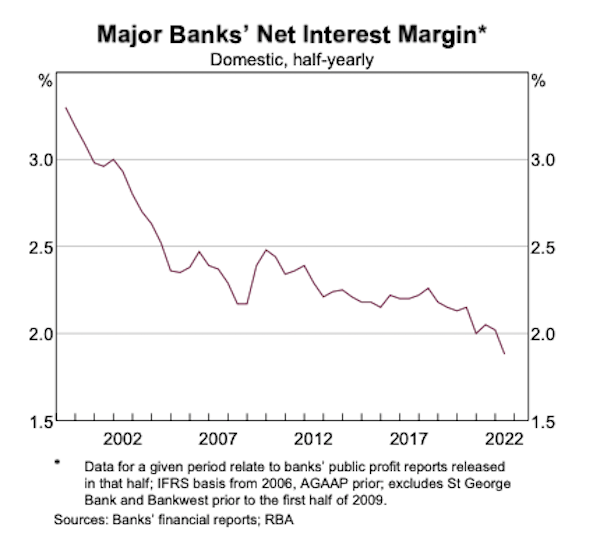

So we have a situation where the net interest margin rises and falls more or less in line with the evolution of the mortgage rates.

I am simplifying a little because the deposit rates do move a little but usually with a lag in relation to the loan rates.

Here is the graph from the RBA Chart Book that shows the Major Banks’ Net Interest Margin from 1998 to now.

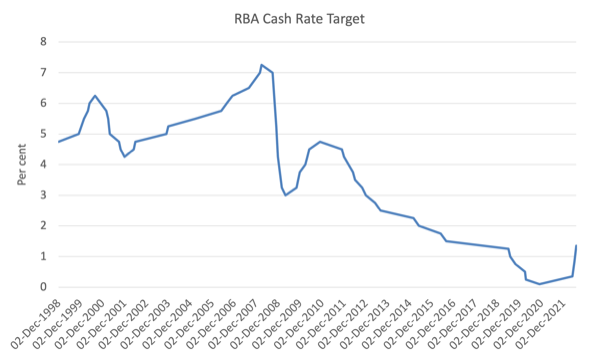

And here is the RBAs Cash Rate Target (the policy rate target they set), which conditions all the other private lending rates predictably.

It is hard to argue from an eye-balling exercise that lower interest rates reduce the profit margin the commercial banks can achieve.

But I also know that eye-balling exercises are really on the beginning of analysis and so we need to understand what the research literature has found on this question.

The trajectory of the RBA policy rate interesting in itself because it discloses the knee jerk way the RBA has operated at times over this period.

In the lead up to the GFC, they started to talk up the inflation threat and pushed rates up only to meet up with the financial crisis triggered by the collapse of Lehmans in August 2007, which saw them run like crazy to lower rates.

Then after a major fiscal stimulus saved the economy from recession, the RBA became influenced by the mainstream nonsense that inflation was about to run wild again as a result of the fiscal injection and so they quickly hiked again.

The problem was that both fiscal and monetary policy danced to the mainstream tune and the economy quickly slowed in 2011-12, which saw the RBA have to acknowledge through action (not any admissions) that they had tightened too early.

And now they are making the same mistake again.

There is another aspect of commercial banking that is not very well publicised.

Commercial banks also hold fairly substantial amounts of contingency funds to safeguard against non-performing loans.

Usually, they hold these funds in fairly liquid, low-risk financial assets, such as short-term bonds and earn some interest return as a consequence.

The yields on these assets tend to move in line with general borrowing costs in the market.

So when interest rates rise generally in the economy, the banks can earn higher returns by reinvesting these contingencies at a higher rate of return.

End result: further gains in profit margins.

What does the research literature say?

On June 17, 2021, the RBA Bulletin published an interesting survey paper – Low Interest Rates and Bank Profitability – The International Experience So Far – which discussed:

… the effect that low interest rates may have on bank profits, and reviews the experience of banks in economies that have had very low interest rates for an extended period.

It is a very apposite survey of the state of knowledge on this issue.

We read that:

The core activity of most banks is lending, and they make money from this by lending at interest rates that are higher than what they pay for their funding. The net interest margin (NIM) (the ratio of net interest income to interest earning assets) is therefore a key indicator of bank profitability. If a decline in policy interest rates results in banks’ funding costs declining by less than their lending rates, then NIMs will narrow and bank profits will decline (all else being equal).

The article provides several reasons to support this view.

1. “As short-term interest rates become very low, a greater share of deposit rates may reach their effective lower bound.”

2. “If lending rates continue to decline when deposit rates have reached their lower bound, then NIMs will narrow” – which is effectively what the previous analysis above is about.

3. “The implications of the lower bound on deposit rates for banks’ funding costs depends on the amount and composition of deposit funding” – as above.

4. “The effect of low rates on banks’ NIMs also depends on how banks adjust their lending rates. ”

5. “Banks typically borrow short term (e.g. deposits) and lend long term (e.g. mortgages). As such, when yield curves flatten (and the difference between long- and short-term rates declines), banks’ NIMs narrow.”

The article also distinguishes between large and small banks, the latter which is more dependent on deposits than the former, which means ” their NIMs might compress more when interest rates decline because of the effective lower bound on deposit rates.”

Their analysis of the extensive literature on the ‘effects of low interest rates on banks’ profitability’ comes to the conclusion that:

Several papers find modest effects of lower interest rates on bank profitability … [another finds] … large effects of interest rates on the profitability of large advanced economy banks. They estimate that a 100 basis point fall in interest rates is associated with a 25 basis point fall in banks’ ROA after one year, with this effect increasing up to 40 basis points when interest rates are very low. The profitability of smaller, less diversified and more deposit-funded banks is more negatively affected by low interest rates

They also find that where banks can charge higher fees and manage lower loss provisions, the impact of falling interest rates on NIMs is smaller.

However, the research literature also finds:

A prolonged period of low rates is found by several studies to have a larger negative effect on bank profits.

On balance, they conclude that:

There is stronger evidence that bank profits decline in prolonged low interest rate environments.

QED.

Conclusion

The logic of banking points to the conclusion that the empirical literature has reached.

There are nuances for sure and individual variations in performance depending on certain characteristics.

But overall, banks prefer higher interest rates than lower rates because their profit margin is higher.

The qualification is that they also hope the higher rates don’t go so far as to drive the economy into recession, which then reduces the demand for loans.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

All this puts the ridiculous profitability of the big Australian banks in an interesting light, given they’ve been operating in a low interest rate environment for an extended period while also delivering very high profits. It almost suggests there might be some kind of anti-competitive behaviour of some sort going on . . . .

What happens next as the Net Interest Margin widens is the appearance of money market funds, who become wholesale depositors. They take retail depositors away from banks, pay a bit more, and then become the end depositor in the bank themselves – while scraping a margin for themselves.

The US already has loads of these and who are confusing the monetarists via their use of the Reverse Repo Facility, and thereby causing a collapse in reserve quantities held at the banks themselves. They are already crying “credit crunch”. Completely clueless.

Commercial banks exists to make a profit.

With interest rates at 0%, there was not much profit to get in the lending business.

So, for more than 10 years now, QE was the lifeblood of the banking business.

You might not believe it, but my bank still pays me interest on my mortgage (last month, they paid me 8,11€) and this has been going on for quite some time (albeit this is about to change, as the euribor/6 month rate went from negative to positive ground, in the last 6th june).

So, the bank was beeing polite with me: they didn’t need me for anything.

Low interest rates encourage people to invest in riskier assets, and get the economy moving forward.

Has with everything else, that comes with a price, so the policy makers have to find an equilibrium point to keep the balance.

The trouble comes when policy makers give away that job to market players.

And then, the market will try to maximize profits, ruining everything.

After some time, many businesses crash and we go into another crisis.

But now, the global economy doesn’t move from crisis to crisis: we are in a permanent multi-crisis.

The GFC ripple effects are still there, and we have to deal with the climate crisis, the pandemic crisis, the refugee crisis, the migrants crisis, the war crisis, the demographic crisis (over population in the global south; aging population in AE), the food crisis, the energy crisis and the inflation crisis – many of them entangled together.

With politicians replaced by Public Relations people and Consultants (many of them with shady agendas), we can’t expect very much from the ones who should lead the game.

I guess that people will have to take matters in their own hands – notwithstanding all the risks of violence that we’ll face going that way – if we want to move ahead.

The Dutch and the Italians are already on the streets.

They are fed up.

Everybody is.

The biggest scandal is when people go for a loan and can’t get a loan because of a poor credit rating are then offered a loan at ridiculous interest rates. Quick Quid and most of the pay day lenders you see on the TV adverts.

It is deemed they can’t afford to repay a loan with a low interest rate but are then given a loan with interest rates between 25- 300%.

The same trick is performed when it comes to taking out a mortgage. The more risky the borrower the more they have to pay. It is deemed they can’t repay a low rate mortgage but are given a higher rate one.

This is the equivalent of price gouging that is carried out in the private sector by those with more pricing power. However, when faced with this type of price gouging by the banks there are very few alternatives compared with finding a cheaper price for your groceries.

Now you have the same thing going on with pensions. Now when people retire who were lucky enough to have had a full pension or a 2/3rds pension. Are being offered to cash those brilliant pensions in and move them into a different type of saving vehicle that are never going to deliver the returns that are promised. The charlatans who were offering this service are charging between 4-6% just for transferring these funds into the new savings fund.

They are deliberately allowed to price gouge and come up with new ways to do it. Quick Quid and a few other pay day lenders went bankrupt. Those that they fleeced only got between 30- 50% of their money back after it went to court and their assets were divided up.

Even some credit unions who are supposed to act differently to a normal bank are now just like a normal bank offering between 1-2% on savings and charging between 5-7% on loans.

Price gouging is a real problem everywhere you look in the private sector because given the option they all want to form monopolies or have just a few players who can rig the system for themselves.

The productivity illusion created by the big tech companies, which rather than make things more efficient have actually “un-scaled” the economy by making it more dependent on cheap labour not less. This is the case from Amazon to the gig economy. The “new app-based economy” is more zero sum than many appreciate. And if the inflation crisis actually forces true efficiency on the system, could actually stimulate some real innovation. I very much doubt that is going to happen when price gouging is rampant.

Reuters is reporting that the French government is planning to take full control of EDF, France’s largest power provider. Germany’s Uniper energy in bailout talks to plug $9.4bn hole. Is this trend going to continue and energy companies in the West going to be nationalised.

First the government bailouts came for the banks they were insolvent; then they came for the airlines Lufthansa was never going to make a profit; then they came for the gas utilities and everybody wondered if there would be anything left for the government to come for before the war ends.

Nationalising these important parts of the infrastructure is the only way to control prices and stop the price gouging and the investment strikes. They only ever realise it when a crises hits and privatise them again afterwards. As the free market tooth fairy has a bigger following than god and they believe their prayers will be answered next time.

Thanks Bill for reminder explanation of banking. If I may just return to yesterday’s comment: “that their (the banks’) share prices have been smashed since interest rates went up.” My thinking is that the misunderstanding there, is in thinking that profitability is measured by trading price of shares. Share price will of course be influenced by profitability but also other investment opportunities, dependent on interest rates, and although a fall in share price will, in the short term, make a difference to the notional wealth of a shareholder, and effect a bank’s ability to raise funds through selling new shares should they want to do so, it won’t stop the lending profits rolling in.

I feel both priveliged and chastened by this blog post perhaps prompted by my ignorant post – ouch! I I am quite willing to admit I have no academic background in economics and Bill is right, I have no knowledge of the literature. Despite the chastening, it was helpful to gain Bills insight into banking. At the risk of digging a deeper hole I will eleborate that the point of my previous post was not to contradict the well established fact that banks profitability, all other things been equal, will be higher in a high interest rate environment than in a low interest rate environment. So maybe sometime in the future the banks will be better off. The only problem is all the other effects of the abrupt rise in interest rates. Bill has predicted that the unnecessary interest rate rises will adversely effect employment, cause mortgage stress, result in reduced lending to home owners and businesses with business failures and possibly result in a severe economic contraction. Consequently bank profits are likely to decline at least for 6 to 12 months and probably for a couple of years. You can argue about the absolutes but in relative terms, downwards seems to be the direction. Will it be losses like in 1992 – who knows but its not out of the question. BOA (probably the best of the US banks – not saying much) share price down 35% in a straight line the last 6 months as interest rates go up and the US slides into recession. The current negative correlation between interest rates and bank share prices is almost 1. My guess is the same fate awaits the Aussie banks. The higher interest rates go, the more the reserve bank overshoots, the worse it will be for everyone including the banks which are heavily leveraged to the economy as a whole.

At the risk of muddying the waters still further where the banks’ apparent appetite for interest rate hikes is concerned, isn’t part of the appeal also the bets that their trading rooms make on those rate decisions?

I don’t know how the internal mud-wrestling between the various divisions within the banks plays out – all we have to go on are the pronouncements made by their various mouthpieces, chief among them their economists and CEOs.

@Simon Fowler, it’s also why “market economists” aligned with banks spent the best part of 12 months lobbying in the financial press for interest rate rises.

Two thoughts.

Does anyone use cheques anymore?

Do banks make more profits on loans or investments?

Are there implications for their investments if rates rise?

I suppose they borrow from each other to leverage their bets?

If I take a loan from the bank and bank credits my bank account, and I keep my money in that bank account, does the bank also pay interest to me because I have now deposit in the bank?

Do we really pay interest to each other? Bank for me for having checking deposit and me to bank for having a loan? Seems really confusing system.

“Bill has predicted that the unnecessary interest rate rises will adversely effect employment, cause mortgage stress, result in reduced lending to home owners and businesses with business failures and possibly result in a severe economic contraction. Consequently bank profits are likely to decline at least for 6 to 12 months and probably for a couple of years. ”

That only happens if the haircut over the collateral was insufficient, and we end up with an actual bad debt that eats into capital buffers.

Otherwise the bank just takes the collateral and sells it, recovering its costs and the interest it would otherwise have charged. The loss is entirely allocated to the collateral owner.

Banks that have been insufficiently conservative may see declines. Good ones will make more money than before.

“Does anyone use cheques anymore?”

That’s a funny question.

When Bill Mitchell and Warren Mosler use checks as examples (for example, “banks could easily find themselves unable to fund another bank’s demands relating to cheques drawn on customer accounts for example”) I must confess I feel a little lost, because I don’t know exactly how they work, as I don’t use them and most people in my country also don’t.

I’m sure that are some people are still using cheques, but in most countries its usage is falling quickly. I don’t have a clue whether this statement is true for Australia, I have never seen their data about cheques.

I have read many works and analyzed many data related to the issue, and I agree with the claim that commercial banks make higher profits when interest rates rise.

What I don’t fully agree is with the claim that banks don’t lend reserves – and I also cannot understand the relation of this claim with the previous one. They don’t seem to be related.

If you are talking about big banks or treating the whole banking sector as a single huge bank (which is an oversimplification), then it makes more sense for me. There are many transactions that end up not consuming reserves because both the customers involved bank at the same bank.

However, if you are analyzing smaller banks, it’s different. While it’s true that a lending operation immediately causes the origination of an asset (receivables from the loan) and a liability (deposit to the customer that borrowed the money), the majority (if not all) of customer will in a few minutes withdraw their deposits or otherwise transfer those resources to other banks, probably the big ones. Hence, small banks need to have the reserves before lending, otherwise they may run out of cash and will be unable to meet the withdrawal and transfer requests.

The reason why the “loan division” of a bank doesn’t need to ask for the “reserve management division” approval for each and every loan transaction is because the latter (together with other “divisions”) will plan ahead and make sure that there is enough cash for at least the next months, possibly the next 12 months at least (depends on each bank’s planning framework). And indeed, there are cases where some unexpected event or crisis happens and the “reserve management division” will indeed ask for the “loan division” to reduce the growth of the lending operations or even to cease it altogether. In that sense, they are not completely separated divisions.

By the way, the “reserve management division” is usually a much more operational team taking care of intraday operations, while there are usually other teams and organizational institutions responsible for the overall liquidity and funding planning and strategy for the bank, including the treasury team, asset & liability management team, finance, the asset & liability committee, the risk committee and maybe others (it depends on the structure of each bank). Those teams are the ones who usually take the call to reduce or stop the lending if necessary, or at least heavily influence the CEO or executive board to do so.

(Here I’m using the term “reserves” as government currency that commercial banks keep deposited at the central bank – I know this naming convention is not universal).

That’s my view so far, not sure if you agree.

If the RBA report that BIll linked is read their conclusion is not definitive at all and is nuanced.

When I began my professional career in the 1970s and into the 1980s, the conventional wisdom among banking analysts was that bank profits tended to increase when interest rates fell. The banking business has changed in some ways since those times and perhaps the same dynamics don’t apply.

Bank profits are a function of margin and quantity of business being written.

When interest rates fall, banks have fixed interest loans which tend to adjust downwards slowly, while their deposit rates adjust downwards quickly. So average margins tend to increase, for a period at least. Falling interest rates also bring improvements in economic activity which increases the level of banking business. So it would not be a surprise if bank profits increased as interest rates fall.

At the lower bound, interest rates on bank sources of funding have a natural downward limit (however negative interest rates are a possibility, which has happened). So margins can get squeezed here.

To argue that banks have an interest in interest rates going up is not that easy an argument to make.

Banks can also effectively tuck away profits in provisioning accounts. Accounting and prudential standards allow them to adjust provisioning accounts for potential losses on loans. These are essentially discretionary. When bank profits are high, provisioning will probably increase. When bank profits are low provisioning can be reversed and added to the bottom line. So at the margin, banks can write the bottom line they want. This factor can effectively allow the banks to smooth out the ebb and flow of profits.

All these considerations, make understanding bank profitability a challenge.

André,

I think you missed where Bill said that , no matter what (currently) all banks can always borrow from the central bank to have the reserves needed to meet the requirement that happens about a week after the loan was made. These loans are made at a low rate for a short time.

Bill also said that a bank can borrow on the ‘overnight’ market from some other bank that got more of the money of recent loans as they were moved around in the national private banking system by customers writing checks and the receiver making a deposit.

By ‘currently’ I mean that the law or policy could change.

As for ‘are checks still used?’, AFAIK, the word ‘checks’ includes using debit cards.

.

“Hence, small banks need to have the reserves before lending, otherwise they may run out of cash and will be unable to meet the withdrawal and transfer requests.”

That’s a chimera.

The default underlying transaction in any move of money between banks is that the target bank becomes the depositor in the source bank. That’s the only way money can move. In other words the target bank becomes a wholesale depositor of the source bank or ‘inter bank lending’ as it is otherwise known.

It can’t happen any other way.

Redirecting that via a third party bank (the central bank) doesn’t change that process. For there to be a forced ‘borrowing’ for one party in the transfer there has to be a forced ‘lending’ for the other party.

Only if the central bank refuses to do the necessary shuffling is there a problem, at which point it will rapidly lose control of the overnight rate it is targeting – right up to the point where a bank will go bust.

Since every central bank in existence has pretty much unlimited intraday overdrafts available to all its participants, the point is moot.

Payment can’t work any other way. Payments and receipts are asynchronous. They are cleared via the central bank using intraday overdrafts and then settled by overnight lending between the banks.

In terms of interbank transfers, the traditional job of the central bank was to get itself out of the middle of the clearing process every day and require all clearing banks to have a balance of zero with the central bank.

There is never an instruction for lending departments to reduce the amount they lend. There is only ever an instruction to change the price at which they lend. Then the standard MMT limit applies – a bank will lend to creditworthy borrowers able and willing to pay the current price of money.

It’s about price, not quantity.

Neil Wilson

Friday, July 8, 2022 at 15:11

“It’s about price, not quantity.”

This statement is generally true when it comes to bank lending, except in case of deep financial and economic crises as during the GFC of 2008. In those times although commercial banks were flushed with liquidity as a result of QE by central banks, they were extremely reluctant to make new loans even to most credit-worthy customers and also to each other in the interbank market, for fear that another Lehman Bros collapse might happen. Uncertainty among banks reached such a level that brought the overnight market to a complete halt, and it took a couple of years before things went back to normalcy.

As for the preference of banks for high interest rate environment I think it is true, because their profitability is directly dependent on the interest rate spread and this tends to widen as CB engages in tight monetary policy.

I suppose another question is why have central banks who after all are representatives of banks

Held such a low interest rate regime for so long (historically) undermining their own interests?

I expect they make enough under any interest rate unless there is a crash.

I think that the previous low interest regime since the global financial crash longer in Japan

and the current increases in interest rates are not DIRECTLY serving self interest but ideological.

That ideology may just be a fig leaf for the self interests of the rich but you gotta fake it to make it.

Steve_American,

“I think you missed where Bill said that , no matter what (currently) all banks can always borrow from the central bank to have the reserves needed to meet the requirement that happens about a week after the loan was made. These loans are made at a low rate for a short time.”

I don’t know if that’s how it works in Australia, but certainly it’s not how it works in many places around the world. What banks can do in most countries is borrowing intraday from the central bank without any interest or penalty charged. Borrowing overnight (or for more days) is subjected to a high penalty and may not be available under certain circumstances.

“Bill also said that a bank can borrow on the ‘overnight’ market from some other bank that got more of the money of recent loans as they were moved around in the national private banking system by customers writing checks and the receiver making a deposit.”

That’s theoretical. Small banks are either required to post collateral (probably government bonds) to be able to borrow from other banks, or may be simply unable to borrow (this requires the other bank to perform and approve counterparty risk analysis and limits). If the small bank already holds government bonds, there is no reason for borrowing in the first place (it can sell the bond), except in some corner cases (the gov bond may take one business day to settle while collateralized borrowing may be immediate, for example).

I also dispute the fact that central banks always act as a lender of last resort. If that was the case, we wouldn’t see any bankruptcy. It may be an American thing that the Fed is always willing to bail out banks, but even then we have Lehman Brothers and other bankruptcies. And the willingness of bailing out banks is a political one that is certainly not so present in some other countries

“AFAIK, the word ‘checks’ includes using debit cards.”

I don’t know, I’m pretty sure debit cards are a distinct instrument and very different from cheques.

Just my thoughts here.

“There is never an instruction for lending departments to reduce the amount they lend. There is only ever an instruction to change the price at which they lend.”

I’m pretty sure there is, I have witnessed that firsthand. There are times when a single bank (or the whole banking sector during a crisis) reduces lending to the less credit-worthy customers and focus on the more credit-worthy ones to reduce the growth or the size of the portfolio (pricing remains the same, what changes is the credit risk threshold). There are other times when banks decide to simply stop issuing loans from a certain portfolio for a time. Period. I have seen that, I’m telling you that this happens in the real world.

It seems that you are seeing the worlds to the oversimplification I just described (that the entire banking sector is a single huge bank). In reality, banks do not act as if they are a component of the banking sector, they act as if they are individual banks and competiting with others.

“The default underlying transaction in any move of money between banks is that the target bank becomes the depositor in the source bank”

I’m completely lost here. I don’t think I could understand what you said there and in the following paragraphs.

But what I can say is that, in the jurisdictions I have experience in (three in south america), interbank lending is something that happens between the big 4 to 6 banks, and not to any other. Small banks take deposits directly from customers and invest excess reserves at the central bank (or buy gov bonds or perform reverse repo). There is no wholesale banking or interbank market to talk about.

To be fair, there is the repo interbank market, collateralized by government bonds. The central bank will always perform repo or reverse repo operations (collateralized with gov bonds) to achieve the target interest rate. This is just a more complex and unnecessary way of implementing remunerated reserves. Banks need to have reserved to be remunerated in the first place.

Again, if the central bank always borrowed the money and acted as the lender of last resort, we would never would have heard about bankruptcy. In my view, the “central bank as a lost resort lender” cannot be a reasonable description of how central banks act.

“I’m pretty sure there is, I have witnessed that firsthand. There are times when a single bank (or the whole banking sector during a crisis) reduces lending to the less credit-worthy customers and focus on the more credit-worthy ones to reduce the growth or the size of the portfolio (pricing remains the same, what changes is the credit risk threshold). There are other times when banks decide to simply stop issuing loans from a certain portfolio for a time. Period. I have seen that, I’m telling you that this happens in the real world.”

That’s a change in the definition of ‘creditworthy’ isn’t it?

Creditworthy changes all the time. Collateral requirements are just a component of price.

What banks never do is say “We’re only lending £100m this month because that’s all the reserves we have”. That’s the quantity we’re talking about.

“It seems that you are seeing the worlds to the oversimplification”

Best not to mind read. That gets you into a world of trouble. You’re not the only one with experience of real world banking.

“I’m completely lost here.”

Do the journals and all becomes clear

It’s fairly straightforward. Without a central bank everything is point to point. At the source bank: DR Customer, CR target bank, and then at the target bank DR source bank, CR customer.

When you introduce a central bank, then you get the same effect but with an extra hop: at the source bank DR Customer, CR central bank reserves, and then at the target bank DR central bank reserves, CR Customer.

Then at the end of the day there is a settlement in the interbank market. The bank that is up does DR source bank, CR central bank reserves, and the bank that is down does DR central bank reserves, CR target bank.

If there is no traditional interbank market due to lack of trust then the interbank counterparty is just the central bank and the clearing position remains the settlement position. But it is the same process – there is clearing on intraday overdrafts, and then settlement.

Any operation that tries to backfill with deposits (which is how British building societies used to operate) will tend to find itself outgunned in the lending market by those with central bank clearing accounts and access to the interbank market – unless there are legal restrictions on who can lend to whom (British building societies had monopolies on mortgage lending until deregulation) or restrictions on who has access to the lender of last resort function at the central bank (again Britain only had four clearing banks until deregulation).

During the 1990s the scramble in Britain was to get a clearing account at the central bank. Now we hand them out to practically anybody.

“It’s fairly straightforward. Without a central bank everything is point to point.”

I cannot even conceive how modern banking would work without a central bank. I don’t know even if it would work at all. There would be government currency at all? I don’t see the point in imagining this fictional world. Also, banks do not need to necessary lend to each other for the banking sector to work.

For example, a public servant earns wages and receives $1000 in currency issued by the government (the central bank) and deposits it at a small bank. In the bank’s balance sheet reserve assets are debited (increased), deposit liabilities are credited (also increased).

Then a customer, let’s say a company, asks for a $1000 loan to pay its taxes. The small bank approves, and hence loan assets are debited (increased) and deposit liabilities are credited (increase), but this time we are talking about the deposit account that the customer company has at the bank.

Then the customer company gives the order to pay the taxes. So the small bank will send the money to the government to pay the taxes, crediting (decreasing) reserve assets and debiting (decreasing) deposit liabilities to the customer company. For this last step, the small bank needs to have reserves available, otherwise it will be unable to meet the customer’s request of paying taxes. Luckily it got a $1000 deposit just before. If it hadn’t, it would try to perform unsecured borrowings with larger banks, which possibly would be denied. As it doesn’t have spare government bonds, it wouldn’t be able to ask for collateralized credit. Hence it would get bankrupted (or probably bailed out by the government if we are talking about the US).

“That’s a change in the definition of ‘creditworthy’ isn’t it?”

I cannot know how every bank works, but in most banks I have worked, they lend based on expected profitability (return of capital is above the minimum required for that kind of portfolio and/or risk profile). There are times they won’t lend even if the loan is deemed profitable because they don’t have the liquidity available. So they will have to prioritize and choose what profitable customers to reject, which are usually the riskier ones (ones with highest probability of default according to models, for example, or least credit score, or whatever, that’s what I’m calling creditworthiness, that is distinct from profitability). They may choose to do the opposite, going for the riskiest ones as they are usually more profitable and rejecting the less risky ones as they are less profitable (although above the profitability threshold), but I’ve never seen this kind of decision being taken.

Of course, those are banks that have faced some kind of liquidity stress or unexpected situations. In more normal situations, business units don’t need to be told to reduce growth and they don’t even need to know what liquidity is, as an asset & liquidity function would have made a plan many months before and addressed all predictable issues.

“I cannot even conceive how modern banking would work without a central bank. I don’t know even if it would work at all.”

What do you think correspondent banking is?

Works every day worldwide. That’s what SWIFT messages initiate. Huge long chains of hops between banks to make international payments.

The central bank is an optimisation within a currency area. It doesn’t change the underlying fundamentals of bank transfers.

“For this last step, the small bank needs to have reserves available, otherwise it will be unable to meet the customer’s request of paying taxes. Luckily it got a $1000 deposit just before. If it hadn’t, it would try to perform unsecured borrowings with larger banks, which possibly would be denied. As it doesn’t have spare government bonds, it wouldn’t be able to ask for collateralized credit. Hence it would get bankrupted (or probably bailed out by the government if we are talking about the US).”

That’s where you go wrong.

The payment will happen because it is the job of the central bank to make sure the payment happens. Banks going bankrupt stop payments happening.

In reality what happens is that the bank makes a transfer to the Treasury, that leads to a system shortage of reserves which either the Treasury relieves by selling the reserves back to the banks via reverse repos (which is how the British DMO does it), or the central bank does a reverse repo to add sufficient reserves to the system, so that they are then on-lent to the bank with the reserve deficit at or below the central bank’s target rate.

Failing that then the lender of last resort will kick in – where the central bank purchases mortgages, loans and the like from the private sector and injects either reserves, or government bonds in what is known as a ‘collateral upgrade process’.

It does all that because otherwise the small bank will bid up the overnight rate above the target rate in order to get reserves to fulfil its shortfall, and the central bank is targeting a rate.

You don’t need reserves available because of the intra day overdraft, and there will always be reserves available to borrow overnight from somewhere because the central bank is targeting a rate and it can’t target a rate if the system is short of quantity. The rate will leap around all over the place killing banks for liquidity not solvency.

The banking system includes the CB, commercial banks and other near- bank institutions. The CB is the monopoly issuer of national currency (paper money), conducts monetary policy, and supervises private banks, among other things. An economy today cannot operate without a CB but it would be possible to function without private banks. In this latter case, individuals and businesses would open all sort of accounts with the CB and do their banking as usual. Private banks play only a parasitic intermediating role and profit at the expense of society. They internalise profits but socialise losses. The fundamental role a CB plays in a modern economy today is one of the reasons why it’s not possible to make the transition to a complete private digital monetary system, like bitcoin etc.

“You don’t need reserves available because of the intra day overdraft, and there will always be reserves available to borrow overnight from somewhere because the central bank is targeting a rate and it can’t target a rate if the system is short of quantity. The rate will leap around all over the place killing banks for liquidity not solvency.”

A private bank may be unable to borrow even there ate other banks with excess reserve. What you are describing is a theoretical world were banks have infinity unsecured credit relations with each other, if I could understand it right.

Also, the last sentence seems contradictory: you are confirming that banks can be killed as a consequence of liquidity issues (which is what I’m claiming all along). If that’s the case, then necessarily this bank was unable to borrow enough liquidity from the central bank or somewhere else, which contradicts your claim that banks will always be able to borrow from the central banks and other banks.

“The payment will happen because it is the job of the central bank to make sure the payment happens. Banks going bankrupt stop payments happening.”

Don’t you concede that bankruptcies exist? If you do, the existence of bankruptcies is a proof that this claim cannot be true. If you don’t, than I would like to understand your view about what happened to Lehman Brothers.

@André,

Lehman Brothers was an investment bank. Investment banks do not accept deposits.

You are quite confused.

AFAIK, advanced nations with CB are smart enough to know that bankrupting a bank because it doesn’t have $100 is just stupid. Someone may benefit, but society as a whole will lose. The CB will have to pay out to make most of the depositors whole. It is far better for the CB to just keep the bank going. A short term liquidity shortfall is no reason to create the mess that a bankrupt bank creates.

I’m just telling you what our Bill has said here many times. Banks don’t lend their depositors’ money. They create new dollars with every loan. AFAIK, for the most part they have large reserve balances. AFAIK, banks are required to have reserves equal to 90% of their total loans outstanding. This is why they borrow from other banks or the CB to get more reserves when there is a shortfall in this requirement. It is not because some customer wrote a check so large that it would bankrupt the bank unless the bank can borrow more money instantly. You seem confused, yet you are claiming experience in the banking industry.

My understanding is that reserves on a bank’s books include all the dollars that the bank has on deposit. Most of those deposits came in in the form of a check or other payment through the CB. Some of those checks will always have been the 1st check from a new bank loan by some other bank. So, the very process of clearing the check by the BC converts the dollars of the loan from “magic money dollars” into real CB reserve dollars. Anyone, jump in a correct me on this.

.

Steve_American,

“Lehman Brothers was an investment bank. Investment banks do not accept deposits.”

For god sakes, what about all the bankruns that have ever happened in history? And all other liquidity-led bank failures? Were they a lie? Northern Rock was never a thing?

“They create new dollars with every loan.”

I’m not claiming otherwise. What I’m claiming is that, in small banks, the created deposits are immediately withdrawn, so the bank must have reserves beforehand or they will face trouble.

“AFAIK, banks are required to have reserves equal to 90% of their total loans outstanding.”

There is no such requirement.

“You seem confused, yet you are claiming experience in the banking industry.”

I have more than 10 years in experience in the banking industry, particularly in liquidity management, and I’m pretty sure I’m not confused.

Your denial that banks can fail of liquidity issues contradicts basic facts like the existence of banks that have failed because of liquidity issues.

MMT followers seem to get so much things right, yet at the same time so much things wrong. I’m sure that Bill and Warren have both claimed that individual banks can fail, but I haven’t seen them detailing how so, which may or may not have added to your confusion.

If central banks will always save banks with liquidity issues, how can banks have failed? There is a straightforward logical contradiction here.

Banks make loans to their customers knowing they eventually have to be funded and that they can be funded.

Banks can finance the loans they make by taking in deposits, by borrowing from the public, borrowing from other banks, borrowing from the central bank, by raising equity, by liquidating assets.

Banks have confidence that they can garner their share of banking system deposits through the normal course of their business.

Just how they mix the balance of funding sources depends on how they believe they can maximize their profits while minimizing the inherent risks in their business and having due regard for their anticipated future cashflows, at the same time complying with prudential standards.

@André,

So, you agree that Lehman Brothers was a bad example, and now want to point to Northern Rock.

I’m no expert, but IIRC Northern Rock was totally crazy in its business plan.

Also, the fact the in the past some banks failed really doesn’t prove anything about now. Maybe the rules were different then.

Maybe the rules are different in the nation where you live, also. Where is that?

I really am guessing here. Maybe the EU is a little different in the the ECB is not a national bank and it may have different rules.

. . . I hope that you know that our Bill thinks the euro was a huge mistake and doomed to failure from the start. Bill says that the ECB is breaking the rules now, and that is the only reason that the EZ has not imploded.

.

Steve_American,

“I hope that you know that our Bill thinks the euro was a huge mistake and doomed to failure from the start”

Yes, I follow MMT since 2011 and have bought many books (all his books I guess), including Eurozone Dystopia, which I highly recommend.

“So, you agree that Lehman Brothers was a bad example, and now want to point to Northern Rock”

Lehman Brothers is not a bad example as it was a bank and had access to interbank funding and rediscount and could have been saved by the central bank, but contrary to what you are claiming, it wasn’t, proving that central banks do not always act as a lender of last resort for banks. If that doesn’t prove the point, I don’t know what does.

I just gave you another example, which is Northern Rock, because you changed your claim and said that it only applied to banks that take deposits but not to investment banks (don’t know the rationale behind it, but there it is, an example). I could give you more examples, like Wachovia and Washington Mutual and so on. Claiming that they have “crazy business plan” (whatever this means) doesn’t change the fact the central banks don’t always act as a lender of last resort. And I don’t think they had a crazy business plan, this seem a sort of excuse to try to explain something you don’t have an explanation for.

“Also, the fact the in the past some banks failed really doesn’t prove anything about now. Maybe the rules were different then.”

We are talking about failures that happened in 2008, not 1910 or the 16th century. The general framework of central banks haven’t changed in any relevant way since 2008. If you do your research, you will find around the world banks that have failed this year as a consequence of liquidity issues.

I cannot avoid thinking that you are interpreting Bill wrong, because, again, he has more than once conceded that single banks can and do fail. I believe that Bill and Warren Mosler exaggerate the ideia that central banks will always act as lenders of last resort or somehow always make banks liquid, and this exaggeration may have confused you (but I’m guessing here).

For example, in this post Bill claimed that “They [banks] always know that they can borrow shortfalls from the central bank at the discount window if worse comes to worse.”

Well, worse came to worse for Lehman Brothers, Northern Rock, Wachovia, Washington Mutual and many others, and they were unable to borrow shortfalls from the central bank and failed. If they were able, they wouldn’t fail. So it’s not “always” that banks are able to borrow, unless you ignore the fact that those instructions went bankrupt.

The countries I have experience with are irrelevant as this point that we are discussing is similar for most countries around the world that are monetary sovereign and have instituted a central bank.

“I believe that Bill and Warren Mosler exaggerate the ideia that central banks will always act as lenders of last resort ”

Have you considered that what happened with Lehman Brothers was a collosal mistake?

The central banks were forced to act as lenders of last resort because when they tried to pretend to be Monetarists the payment system started to seize up and collapse completely.

That’s when we saw QE start up, deposit insurance being raised to 100%, etc, etc. Exactly as MMT predicted would happen. The central bank wasn’t in control. It was servant to events. The accelerator and brake their belief systems told them would work, didn’t work. They had to change course very rapidly as reality forced their hand.

Killing illiquid banks will cause a systemic crisis that will force the central banks to change their policy. That is the lesson from 2008. You cannot deny policy was rapidly changed. The central bank were unable to control events with their original levers.

Which is why the recommendations from MMT is to drop all the pretence that central banks can effectively control credit while at the same time maintaining a functional payment system in all circumstances.

You have to pick one or the other. Once you have ZIRP, for example, introducing central bank digital currencies (aka everybody’s bank account is really at the central bank) becomes very straightforward. Bank’s balance sheets then have majority wholesale deposits directly from the central bank against whatever loans the prudential management of the central banks says banks are allowed to write. The central bank puts its money where its prudential mouth is.

“he has more than once conceded that single banks can and do fail”

Banks fail when they are insolvent. Forcing banks to fail when they are merely illiquid just causes payment crises and puts the price of lending up which reduces capital development in an economy.

Why do that?

So, André, Neil Wilson says that things changed after 2008. The CBs learned the error of letting Lehman Brothers go bankrupt. Are your other examples also from around 2008? IIRC Northern Rock’s business plan was to only borrow from other banks and not compete for any deposits, however it is a vague memory.

IIRC, I discovered MMT in about 2007 and Bill’s blog later than that. I started with Randall Wray’s Primer.

Bill is writing in the present tense and so am I. Neil says that now is different from the recent past.

I’m sure that you know that the EU and especially the EZ are maybe not doing things in exactly the ways that Bill says the fiat currency nations are doing. Maybe your “liquidity dept.” is necessary in an EU nation. It isn’t needed in the US or Aust., according to Bill.

.

Neil Wilson,

“Why do that? [Forcing banks to fail when they are merely illiquid]”

I wouldn’t call it “forcing them to fail”. They have done liquidity mismanagement by themselves, no one forced them. Anyway, irrespective of the reason one may give to your question, or whether you believe it was a collosal mistake or not, that fact is that central banks have done that many times.

Steve_American

I have already gave many examples, and you can easily research for yourself and see with your own eyes that, to this day, banks are still failing as a consequence of liquidity issues. You don’t have to look to the Eurozone, you can look at many other monetary sovereign countries. You don’t have to believe me or take my word, just see for yourself.

It seems that you are failing to acknowledge facts into your theories / ways of seeing the world. That is what mainstream economists do.

Many countries (I would dare to claim that most) have currently both regulatory supervision that helps to prevent bank failures and deposit insurance schemes that help to alleviate the consequences of bank failures, and this is more than enough to prevent adverse effects arising from failure. A bail out is not necessarily the desired plan of action nor the practice more aligned with the public interest.

Also, central banks and regulators usually tend to facilitate the selling of the failed banked to other “healthy” banks to avoid bankruptcy and its adverse effects, but it’s not always that the market is interested in buying the failed bank.

I would add the “too big to fail” is indeed a thing and I guess it’s reasonable to assume that most big banks around the world would be either bailed out or nationalized if they failed. My dispute is that this practice (central banks always acting as lenders of last resort) is not generally applicable to smaller banks.

Reality is always more complicated than theory.

That is why you need a lens to make sense of it.

The difference between insolvency and illiquidity is that the former means a bank has negative net worth, that is liabilities are greater than assets. In this case the CB will ask the bank either to increase its share capital or be taken over by a healthy bank; failure to do so the CB will revoke its license and the bank will close down. Illiquidity, on the other hand, implies that the bank maintains positive net worth but can’t temporarily meet its reserves obligations by accessing the overnight market. It is in this case that the CB acts as “lender of last resort” by allowing the bank access to the discount window and borrow at the discount rate.

I hope that this clears up the noted misunderstanding between insolvency and illiquidity.

Demetrios Gizelis,

What I’m claiming is that evidence shows us that it is not always the CB will act as a “lender of last resort” for illiquid banks, contrary to what some MMT followers imply.

André,

OK, I’ll concede your point, that some small number of small banks in some nations may be allowed to fail over Illiquidity issues. Will you concede our point that this is a choice by the CB that could always solve their temporary liquidity issue? Except, not in the EU, and especially the EZ.

.

“Will you concede our point that this is a choice by the CB that could always solve their temporary liquidity issue?”

The monetary sovereign country (and its central bank) will always bo able to save any bank, any non-financial company and any individual from bankruptcy (even if the bankruptcy is no caused by liquidity issues), as it is the issuer of the currency. I do agree with that.

That doesn’t mean they should nor that they do it on a regular basis.

I am new here, so I’m hoping someone can clarify the reserves-loans-deposits “funding” controversy a bit for me. Here’s a hypo to illustrate what I’m thinking involving a bank that persists in (1) not taking deposits and (2) nevertheless making loans / creating broad money.

o Bank A lends $5 million to Borrower. It just creates an account and credits the account $5 million, recognizing the loan as an offsetting $5 million asset. There are no direct involvement of central bank reserves in this transaction. (Broad) money has been created out of thin air.

o But what if the Borrower instructs Bank A to wire the funds to Bank B instead of maintaining a deposit account at Bank B?

o Then Bank A recognizes an asset in the form of the loan, but there is no corresponding liability in the form of a deposit at Bank A. Instead, the transaction settles by debiting Bank A’s reserve balance and crediting Bank B’s reserve balance, with Bank A recognizing a new asset (the loan) and crediting its reserve balance. The balance sheet thereby balances.

(Alternatively, Bank A and Bank B could settle the transaction with a clearing house, with appropriate adjustments to the amounts of funds held by the banks with the clearing house).

o If Bank A continues to make loans to borrowers who immediately deposit the lent funds at Bank B, then Bank A will continue to see its reserve balances decrease and Bank B will continue to see its reserve balance increase-but what are the implications of that?

o In an environment of superabundant reserves, the implications might be delayed. But in an environment of scarce reserves, Bank A will soon want to stem the outflow of its reserve balances. Otherwise, it will be unable to settle transactions at the central bank, which will emerge as a constraint to underwriting (dare we say “funding”) new loans, right? Another way of looking at the problem would focus on the balance sheet: Bank A would have no way to balance its balance sheet if it persists in making loans (i.e., increasing its assets) with no offsetting accounting event. (Formerly, the debit to the asset side (i.e., the increase in loans outstanding) was balanced by a credit to the asset side (i.e., the decrease in reserve balances). If a bank persists in not taking deposits, then it must “fund” loans out of continually diminishing reserves, which will, at some point, emerge as a real constraint on further lending.

o The way to remedy the situation is to obtain other sources of funding that will maintain a net reserve position. Bank A could replenish reserves by starting to take deposits, or by looking to repo markets or to the central bank (to discount its assets). Repo will only work if the bank has swapped some of its loans for high quality securities, and the central bank will presumably not be keen to allow access to the discount window (i.e., provide public support) for a private bank that persists in creating assets (loans) for itself without being able to source its own funds. In that latter case, you’d have fully public financing and fully privatized seignorage. However, if Bank A decides to attract deposits, then it will experience inflows of cash and positive reserve balance adjustments from other banks — e.g., the bank of the employer that pays wages to the worker who now deposits her wages at Bank A. In the process, it will also be able to make a corresponding credit to reserves or cash that enables it to debit future loan balances — i.e., it removes the accounting constraint on further loan origination.

o Are things any different in an environment of superabundant reserves? It seems to me that describing aggregate banking system reserves as “superabundant” requires some conceptual clarification in this context. Reserves are obviously superabundant for purposes of deploying the traditional open market monetary policy toolkit to set and maintain interest rates, but they are not superabundant when it comes to balancing the asset side of Bank A’s balance sheet.

o Similarly, maybe the controversy about whether reserves and deposits “fund loans” requires some more precise specification? If we take it to refer to a sequential logic whereby the bank checks its reserve balances and deposit levels, then determines how many loans it can make, then the statement is clearly wrong. But if we take it to refer to a balancing logic whereby the bank must ensure that it has an acceptable mix of reserves, deposits, and other financing in place to ensure it can avoid a unidirectional, unchecked reserve drain … then maybe it has some important explanatory power?

Robb,

IIRC, back before 2008 the Northern Rock bank in UK was doing that. IIRC, it was borrowing from other banks because that was cheaper than attracting depositors. It went belly up in 2008/09.

Try this source. A 51 mon video. between the 6 and 15 min. marks he talks about why mainstream econ. is wrong. And after the 24 min. mark he talks about banking.

. . . Richard Werner. What’s wrong with mainstream economics.

.

Regarding my earlier post, the third paragraph should read:

But what if the Borrower instructs Bank A to wire the funds to Bank B instead of maintaining a deposit account at *Bank A*?

Robb

Friday, July 15, 2022 at 5:11

“Here’s a hypo to illustrate what I’m thinking involving a bank that persists in (1) not taking deposits and (2) nevertheless making loans / creating broad money.”

Such a bank does not exist in the real worlds, so I don’t really understand the point of going through this elaborate exercise, which is correct in its internal logic but inaplicable in reality.

Non-mainstream economists (Richard Werner most outspoken) have rejected the sequence that extra reserves create loans and instead argue that loans are created “ex nihilo” by increasing both sides of the bank’s T account by the loan amount. Thus, the bank’s liabilities increase as new deposits are added to the borrower’s account and simultaneously its assets rise with the additional loan.

If our bank maintains sufficient reserves at the CB, no further adjustments are needed even in the case the borrower withdraws the funds. In the opposite case the bank must seek to satisfy its reserves requirements with the CB, and there are a number of alternative ways this can be done. One of them is by accepting deposits from savers, which for the majority of banks is the most cost efficient ways and probably it is why traditionally banks compete with one another for deposits. I remember once banks offering toasters to new customers for their deposits when there was a ceiling on deposits’ interest rates, during the old good era of high bank regulation regime.

Robb,

“Bank A lends $5 million to Borrower. It just creates an account and credits the account $5 million, recognizing the loan as an offsetting $5 million asset. There are no direct involvement of central bank reserves in this transaction. (Broad) money has been created out of thin air.”

Just to confirm: at this point, Bank A has a $5M loan asset and a $5M deposit liability, right? As you can see, the loan created the deposit.

“But what if the Borrower instructs Bank A to wire the funds to Bank B instead of maintaining a deposit account at Bank A?”

Maybe I will just say the same thing you said but with different words (maybe not). First of all, in order to honor the transfer instruction, Bank A must hold reserves at the central bank, otherwise it will tell its customer something like “Sorry, we are facing some technical issues and cannot fulfill your request” or something like that. Reserves are not created by the bank, so the bank cannot simply issue reserves. It must acquire them by attracting deposits or borrowing from other banks or selling government bonds or borrowing and giving the bonds as collateral etc.

If Bank A already has reserves for whatever reason, it will honor the transfer instruction and the accounting is simple. The deposit liability is debited (reduced) and the reserves asset is credited (reduced). If it doesn’t have the reserves, probably the transfer is not made and nothing changes in accounting terms (but the customer will probably be pissed or very worried).

“Bank A would have no way to balance its balance sheet if it persists in making loans”

Double-entry accounting will make sure that the balance sheet always balance, no matter what, even if the bank goes bust. So Bank A would always be able to balance its balance sheet. What it wouldn’t be able to do without the reserves is honouring its customers transfer requests.

Loans do not fund themselves. The reserves used to settle the transfer probably came from deposits from other customers (that transferred their money to Bank A, not the ones that are taking loans), from wholesale funding with other institutions, or from Bank A’s own shareholder equity and retained profits.

“Are things any different in an environment of superabundant reserves?”

I don’t know what you mean by “superabundant reserves”.

What I would claim, and I don’t know if that’s what you are asking about, is that in normal times the big banks will always be able to attract sufficient funding via deposits, interbank operations, wholesale funding or whatever. The question is not whether they will be able to attract sufficient funding or not, but the price (interest, yield, fees or whatever the remuneration is) they will have to pay. So normally banks are worried whether the business will be profitable, not whether they will run out of cash. Of course, if the bank decides to triple the amount of deposits overnight it probably will be unable to do so, but this is an extreme example. In a more normal growth rate, big banks will always be able to seek sufficient funding. That’s not necessarily true for smaller banks even in normal times.

In crisis, the scenario changes, and even big banks may be unable to attract funding so easily. If they do not manage adequately their liquidity, they may go bust.

Hope I have helped.

Demetrios: Many thanks for response.

You write: “Such a bank does not exist in the real world, so I don’t really understand the point of going through this elaborate exercise, which is correct in its internal logic but inapplicable in reality.”

I agree with your premise, but I am trying to figure out *WHY* that’s the case in order to explore a limit, or a tension, to the “loans fund deposits, deposits don’t fund loans” mantra. I get Werner’s basic point, but I think that the MMT/Werner/endogenous money folks (of which I am one) and the orthodox “deposits fund loans” folks seem to sometimes talk past each other. I think it might make more sense to say something like “deposits are not a precondition to additional loan origination and money creation, but a reduction in deposits could emerge as a constraint to additional loan origination and money creation through the central bank’s clearing function, which requires (as a functional matter, not as a legal-regulatory matter) the bank to maintain reserves that are proportional to its money creation.”

You also write: “If our bank maintains sufficient reserves at the CB, no further adjustments are needed even in the case the borrower withdraws the funds. In the opposite case the bank must seek to satisfy its reserves requirements with the CB, and there are a number of alternative ways this can be done.”

I agree with this provided the reference to “reserve requirements” is a functional requirement, not a legal-regulatory requirement. After all, there are no reserve requirements in the U.S. right now, and our hypothetical Bank A nevertheless could not, as you say, exist. (This is basically the point I make in the last sentence of my earlier paragraph).

André: Many thanks for the response.

You write: “Double-entry accounting will make sure that the balance sheet always balance, no matter what, even if the bank goes bust. So Bank A would always be able to balance its balance sheet. What it wouldn’t be able to do without the reserves is honouring its customers transfer requests.”

What would the corresponding entry be when Bank A (1) originates a loan by wiring funds to Bank B, but (2) has run out of reserves entirely. Can double-entry bookkeeping provide an answer, or is this just a logical impossibility? And if it’s a logical impossibility, then that begins to expose a tension in a *certain* simplistic interpretation of the “loans fund deposits” argument, no? Lack of reserves emerges as a hard constraint on additional private money creation at Bank A, and Bank A will need to acquire reserves, the cheapest means of achieving that is usually by attracting deposits. So there *is* some universe in which deposits emerge as a constraint to additional loan creation. I’m not saying that this disproves the basic MMT/Werner “loans fund deposits” argument, but it just requires us to specify it more clearly, perhaps, as:

“Deposits are not a precondition to additional loan origination and money creation, but a reduction in deposits could emerge as a constraint to additional loan origination and money creation through the central bank’s clearing function, which requires (as a functional matter, not as a legal-regulatory matter) the bank to maintain reserves sufficient to support to its money creation.”

You also write: “I don’t know what you mean by ‘superabundant reserves’.”

I just mean that the post-QE banking environment (in the US, at least) is such that banks hold reserves in excess of legal-regulatory requirements. (In fact, the Fed has abandoned legal reserve requirements altogether for the time being). In such an environment, we can assume that Bank A, before it embarks on this course, has a significant amount of reserves to begin with. As it persists in making loans and creating money without securing a corresponding source of reserves (here is where the ambiguity with the term *FUNDING* becomes relevant) with which the settle outflows when borrowers inevitably (1) ask Bank A to send their borrowed funds to Bank B etc. or, alternatively, (2) begin to use / draw on the lent funds initially deposited with Bank A.

Robb,

“loans fund deposits, deposits don’t fund loans” is not the MMT mantra. It is “loans aren’t funded from existing reserves”.

Every loan has to be funded in some way. It can be funded by an increase in deposits, an increase in borrowing from the public, an increase in borrowing from other banks, an increase in borrowing from the central bank, an increase in equity or from the net operating cashflows of the lending bank.

A bank knows that when it writes a loan it will get its share of banking system deposits in the normal course of business and that it has a capacity to borrow if required. It need not be directly concerned with how it will fund the loan when it writes the loan.

The mix of funding sources depends on how the bank believes it can maximize its profits while minimizing the inherent risks in its business and having due regard for its anticipated future cashflows, at the same time complying with prudential standards.

Henry Rech,